Abstract

J-wave pattern has been recognized as an arrhythmic risk marker, particularly in myocardial infarction patients. Mechanisms underlying J-wave development in ischemia remain unknown. In myocardial infarction model, we evaluated activation time delay as a prerequisite of J-wave appearance and predictor of ventricular fibrillation. Body surface ECGs and myocardial unipolar electrograms were recorded in 14 anesthetized pigs. 48 intramural leads were positioned across ventricular free walls and interventricular septum. Myocardial ischemia was induced by ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery and the recordings were done during 40-minute coronary occlusion. The local activation times were determined as instants of dV/dt minimum during QRS complex in unipolar electrograms. During occlusion, ventricular local activation time prolonged in the middle portion of the left ventricular free wall, and basal and middle portions of septum, while J-waves appeared in precordial leads in 11 animals. In logistic regression and ROC curve analyses, activation time delay at a given time-point was associated with J-wave development, and a longer activation time was associated with ventricular fibrillation appearance. In experimental coronary occlusion, activation delay in ischemic myocardium was associated with generation of the J waves in the body surface ECG and predicted ventricular fibrillation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

J-wave pattern is recognized as an electrocardiographic phenomenon manifesting as an additional low-frequency wavelet during the terminal part of QRS complex or QRS/ST junction1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Originally, this phenomenon was regarded as a normal variant, especially in young subjects9, but subsequently has been considered as presenting a risk marker for malignant idiopathic ventricular tachyarrhythmias5. Recent evidence suggest that appearance of the J-wave pattern in patients with acute myocardial ischemia indicates the presence of arrhythmic substrate thus further increasing arrhythmic risk10,11,12,13,14,15. In an experimental setting, we have recently shown the appearance of J-wave during the progression of acute ischemia, which was highly predictive for ventricular fibrillation (VF)16, however the exact mechanisms underlying J-wave development could not be elucidated from the study based on close-chest myocardial infarction model.

The mechanism of the J-wave genesis in acute ischemia remains controversial. There are two main lines of evidence suggesting repolarization or depolarization abnormalities to underlie this phenomenon. The first line was suggested on the basis of studies of the distribution of electrophysiological properties on a transmural axis of the canine left ventricular (LV) wedge preparation17. The direct reason for the J-wave formation has been reported to be a transmural difference in a transient outward current density. This ECG phenomenon has been shown to be accentuated by increased vagal tone and bradycardia18, an observation supporting the suggested repolarization-related mechanism for the J-wave. However, a different mechanism could operate in ischemic conditions characterized by a conduction delay in the affected regions. The study by Nakayama et al.19 demonstrated that in patients with an acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction the J-wave amplitude was augmented in tachycardia, which supported the conduction delay-related mechanism of the early repolarization pattern. Meijborg et al.20 demonstrated that reduction of sodium current led to development of the J-wave pattern. Simulation studies21,22 demonstrated that prolonged activation in ischemic conditions produces an “overlap” of depolarization and repolarization potentials manifesting as the J-wave pattern. However, there is a lack of evidence for this concept based on direct measurements in the in vivo whole heart.

Thus, contribution of abnormal depolarization to J-wave generation and VF development in the ischemic conditions is unclear. In the present study, we aimed at evaluating activation time delay as a prerequisite of J-wave appearance and predictor of VF in open-chest porcine model of myocardial infarction.

Material and Methods

Experiments were performed in 14 domestic pigs (35.4 ± 7.5 kg body weight, 6 males, 8 females). The procedures conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition published by the National Academies Press (US) 2011 and were approved by the ethical committee of the Institute of Physiology of the Komi Science Centre, Ural Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences. Animals were anesthetized with zoletil (Virbac S.A., Carros, France, 10–15 mg/kg, i.m.), xylazine (Interchemie, Castenray, Netherlands, 0.5 mg/kg, i.m.) and propofol (Norbrook Laboratories Ltd, UK, 1 mg/kg, i.v.). The animals were intubated and mechanically ventilated. The thorax was opened by a midsternal incision and the pericardium was cut. In order to prevent hypothermia-related phenomena including J-wave generation and slowing of activation spread, the temperature in pericardial cavity was maintained at 37–38 °C by irrigation with warm saline and heating the room air.

Body surface ECGs were recorded in 6 limb leads and 6 precordial leads. The latter corresponded to the standard V1-V6, but the leads V4-V6 were shifted downward to the level of xiphoid basis in order to minimize possible thoracotomy effects. This modification also took into account the vertical position of the pig heart in the thorax.

Flexible plunge electrodes were drawn transmurally through the anterolateral and anterior ventricular wall that intramyocardial leads were positioned in subepicardial, midmyocardial and subendocardial layers of the left ventricular (LV) free wall, interventricular septum (IVS) and right ventricular (RV) free wall at the apical, middle and basal levels of ventricles (Fig. 1). The electrodes were fabricated with isolated 70-µm copper wires, fixed with a knot on a 0.8-mm vicryl thread. Each electrode bore 16 lead endings. In order to induce coronary occlusion, a polycaproamide ligature (№ 3-0) was placed (not tied first) around the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery just distal to the origin of the first diagonal branch. After the electrode and ligature placement, the heart was allowed to stabilize for 30 minutes. Myocardial ischemia was induced by LAD ligation. The location (origin of the first diagonal branch) and duration (40 min) of coronary occlusion was chosen according to our previous work16. At the end of each experiment, the animals were euthanized by an intracardiac injection of potassium chloride overdose, the heart was excised and Evans blue dye (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH, Germany) was injected into the LAD, left circumflex and right coronary arteries with LAD ligated. The dyed zone identified the perfused or nonischemic area (Fig. 1) thus allowing assessment of the localization and extent of the ischemic myocardium.

Positioning of intramural leads in the ventricles. (A) A schematic presentation of a typical location of the electrodes in relation to ventricular walls, cavities and ischemic regions on a cross-section. (B) A photograph of outside appearance of the explanted heart with electrodes in place after Evans blue infusion. See input (on the LV) and output (on the RV) points of three electrode-bearing threads. (C) A photograph of the ventricular cross-section with electrode-bearing thread (white arrows) in place coming through the LV and RV cavities and free walls. Dye-impregnated areas identify for the perfused (nonischemic) regions and a dye-free septum and adjacent free walls show the ischemic regions (black arrows). LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Unipolar electrograms in a total of 48 myocardial leads were continuously monitored and recorded simultaneously with body surface ECGs by means of a custom-designed high-resolution system (16 bits; bandwidth 0.05 to 1000 Hz; sampling rate 4000 Hz). At least 10-seconds duration recordings were done at baseline and at 1, 2.5, 5, 10, and then every 5th minute until the end of 40-minute coronary occlusion. Local activation time (LAT) in each myocardial lead was measured from the QRS onset to the instant of a minimum of dV/dt during QRS complex23,24,25. For each recording, a maximal LAT was determined as the longest LAT throughout myocardium irrespective of a lead where it was observed. The presence or absence of J wave in the body surface ECGs was checked in the same time-points. According to the consensus document6, the J-wave presence was confirmed when there was a terminal QRS notching or slurring in two or more contiguous leads except V1-V3 with J-peak ≥ 0.1 mV and no QRS prolongation in leads free of the supposed J wave.

Data are expressed as medians and interquartile intervals. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 23 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to validate application of ANOVA post-hoc tests; otherwise, Wilcoxon and Fridman tests were applied for paired and multiple comparisons, respectively, within the same groups of animals. Logistic regression analysis and receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis were used to assess relationship between intramural LATs and appearance of J-waves on the surface ECG and VF development. The differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

LAT dynamics

At baseline, we observed an expected activation pattern with relatively early LATs in subendocardial and intramural myocardial layers and relatively late LATs in subepicardial layers. Rapid intramural spread of activation resulted in a nearly simultaneous excitation of different parts of ventricular myocardium [median LAT ranged from 18 (IQR 17–22) ms in the LV apex to 20 (IQR 17–22) ms in the basal IVS and 20 (IQR 19–24) ms in the middle RV] with the only exception of the RV base that was activated later than the rest of myocardium [median 24 (IQR 22–30) ms, p < 0.001].

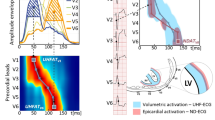

Coronary occlusion induced typical changes of ventricular electrograms in the affected regions, essentially in the anterior parts of basal and middle areas of LV free wall and IVS, observed as a prolongation of QRS complex duration and LAT delay. LAT prolongation was nonuniform across ventricular myocardium (Fig. 2). While the nonischemic areas had stable LAT during the occlusion period, the areas identified as non-perfused by postmortem investigation and presenting typical ST-segment elevation on local intramyocardial electrograms could have either increased or unchanged LATs (Fig. 2, panel A). In the cases of extreme LAT prolongation (Fig. 2, panel A, top records), QRS complex of the unipolar ventricular electrogram was distorted mainly by a R-wave widening. Also, the initial portion of QRS complex might be distorted as can be seen by a Q-wave loss at the 5-min time point (Fig. 2, panel A, top record).

Regional differences in LAT prolongation at 5 min of LAD occlusion. (A) Representative unipolar electrograms recorded in the same animal demonstrating different behavior during coronary occlusion. IVS base demonstrates ischemic changes with activation delay. See dramatic R-wave prolongation and loss of q-wave at 5-min point. Middle part of IVS demonstrates ST-segment elevation without significant activation delay, whereas nonischemic LV apex shows no changes. (B) LAT medians (lines), interquartile range (boxes), mean (crosses) and limits (error bars) in different myocardial regions at baseline and 5 min after LAD occlusion. (C) Maximal observed LATs irrespective of lead localization at baseline and 5 min after LAD occlusion.

The most pronounced effects were observed at the 5th minute of occlusion. At this time-point, a marked prolongation of LAT medians as compared to the baseline state was documented in the middle portion of the LV free wall, basal and middle portions of IVS, while the rest of myocardial regions did not demonstrate statistically significant changes of LAT (Fig. 2, panel B). The greatest activation delays during occlusion were found in the intramural and subendocardial layers of IVS and LV anterior or anterolateral wall. The maximal LAT throughout myocardium irrespective of lead localization demonstrated a significant increase from baseline to the 5 min of occlusion (Fig. 2, panel C). LATs in ischemic regions partly restored after the initial (5-min time-point) activation delay, and then again prolonged at 20–30 min (Fig. 3, panels A-C), though this second-window prolongation was less pronounced. The most evident biphasic dynamics was observed for the maximal LAT (Fig. 3, panel D), which was associated with the LATs of the middle LV free wall and middle IVS (B = 0.76; 95% CI 0.61-0.90; p < 0.001 and B = 0.80; 95% CI 0.51–1.09; p < 0.001, respectively).

Dynamics of local activation times (LATs) during coronary occlusion in different parts of LV (panel A), IVS (panel B), RV (panel C) and maximal LAT throughout all intramyocardial leads (panel D). Apex, Middle and Base designate different portions of the corresponding chamber walls on an apicobasal axis. *p < 0,05 vs baseline; #p < 0,05 vs 5 min time-point. LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; IVS, interventricular septum; Max LAT, maximal local activation time, n = 14.

Association between local activation delay and J-wave appearance

Prior to coronary occlusion, body surface ECG demonstrated no spontaneous J-wave pattern and no pharmacological or surgical interventions led to its development. Consistently with LAT prolongation during ischemia, J-waves appeared in precordial leads (most frequently in leads V4-V5) in 11 animals (nine animals at the 2.5–5th min; one animal at 20th min; one animal at 35th min of LAD occlusion) (Fig. 4). Three pigs demonstrated no J-waves in the body surface ECG leads during coronary artery occlusion.

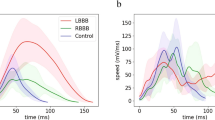

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, maximal LAT was associated with J-wave development (OR = 1.16 95% CI 1.10–1.23; p < 0.001). ROC curve analysis (Fig. 5, panel A) also demonstrated significant association between LAT and J-waves on body surface ECG (AUC 0.94, p < 0.001) and the optimal cut-off for the longest LAT in the ischemic regions > 45 ms predicted J-wave appearance with sensitivity 0.86 and specificity 0.90, negative predictive value 0.92 and positive predictive value 0.82.

In order to determine which locations contributed significantly to the J-wave formation, uni- and multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. At a first step, averaged LAT of all studied regions were tested as predictors of J-wave development in a univariate analysis; and those that demonstrated significant association were included in a logistic regression model in the multivariate analysis at a second step (Table 1). As a result, LAT in the basal IVS, middle IVS and middle LV free wall were shown to be independent predictors of J-wave.

Association between local activation delay and ventricular fibrillation

Before LAD ligation, no VF episodes were observed, whereas five pigs experienced VF during coronary occlusion. In a univariate logistic regression analysis, maximal LAT at a given time-point was associated with VF presence (OR = 1.04; 95% CI 1.01–1.07, p = 0.010). Similarly, the ROC curve analysis (Fig. 5, panel B) demonstrated significant association between maximal LAT and VF development (AUC 0.87, p = 0.006). A cut-off value >55 ms predicted VF with sensitivity 0.80 and specificity 0.83, negative predictive value 0.99 and positive predictive value 0.17. A cut-off value of >69 ms predicted VF with sensitivity 0.60 and specificity 0.91, negative predictive value 0.98 and positive predictive value 0.21.

In order to find out which specific region was responsible for the development of VF, we tested averaged LATs in the regions with significant ischemia-related activation delays (these same regions were found to be the only contributors to J-wave generation) as predictors of VF. The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that only IVS LATs were the independent predictors of impending VF (Middle IVS: OR = 1.07 95% CI 1.01-1.13, p = 0.013; Basal IVS: OR = 1.19 95% CI 1.07-1.33, p = 0.002).

Discussion

Summary

The main findings of the present study are as follows: (i) LAD occlusion led to LAT increase associated with J-wave appearance on the body surface ECG; (ii) impending VF was predicted by LAT prolongation in ischemic regions; (iii) the LAT associated with impending VF was significantly longer than the LAT associated with J-wave development and confined to the IVS region.

Activation delay as a cause of J-wave

There is a long-lasting debate on the origin of the J-wave pattern. Its alternative name “early repolarization pattern” implies its relation to the repolarization process, specifically to the potential difference during action potential phase 117. Presenting no objections against the role of repolarization in the J-wave pattern generation in a general sense, our experimental data suggest that in the acute ischemia setting, the J-waves were strongly associated with occurrence of abnormal depolarization and were likely to be the consequence of it. Several considerations support this hypothesis.

We measured LAT as an instant of the steepest downslope of the QRS complex of unipolar ventricular electrogram. This approach was validated in an earlier study by Kleber et al.24. Using this method that provided the means for in vivo evaluation of activation wave spread across ventricular walls, we observed the expected activation slowing in the ischemic regions with the most pronounced LAT delay being associated with the J-wave pattern. This activation delay developed progressively in time and space with transition from the typical QRS morphology to the grossly distorted wide QRS complexes which were often attended by the change of initial portion of QRS (either loss or development of the q wave) (Fig. 2, panel A, and Fig. 4, panel A). The fact that we observed the early QRS distortions (which definitely could not be ascribed to repolarization) in parallel with J-wave development supports the idea that the depolarization abnormalities are causative of these ECG changes including J-wave formation.

J-wave formation was associated with LAT prolongation in specific ventricular areas. Since the site of occlusion was the proximal part of LAD artery, the areas demonstrating the significant ischemia-related activation delay were the anterior regions of the basal and middle part of IVS and middle part of LV free wall. These very areas demonstrated significant association between LATs and J-wave pattern. In previous studies, J-point elevation was reported to correlate with a thickness of IVS26. Taken together, these findings suggest that the J wave can develop in conditions with prolonged activation of IVS and adjacent ventricular areas.

Local activation time as a predictor of VF

Whatever the cause of the J-wave pattern, this electrocardiographic phenomenon appears to be a risk factor for malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias3. In the present study, we provided evidence suggesting J-wave association with depolarization abnormalities. Moreover, our findings suggest that further delay of LAT in the ischemia-affected myocardial region strongly predicts development of ischemia-induced VF.

LAT prolongation was associated with impending VF in a manner similar to LAT association with J-wave pattern. However, LAT predicting VF were longer than those predicting J-wave pattern for the similar levels of sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 6). It could be suggested that the J-wave was generated when LAT exceeded a certain threshold value and significant risk for VF arose when LAT prolonged somewhat further. Furthermore, development of precordial J-wave was associated with prolonged LAT in three regions: basal IVS, middle IVS and LV free wall; whereas only IVS LAT prolongation independently predicted the VF episodes. The LATs of the middle LV free wall and septum, but not of the basal septum were associated with maximal LAT. This kind of association implies that not only the mere extent of LAT prolongation was essential for VF, but some ventricular regions might be more vulnerable for arrhythmic stimuli than the others. These abovementioned distinctions between LAT-VF and LAT-J-wave relationships can explain why the J-wave pattern is not always followed by malignant arrhythmias.

Schematic relationship between the range of maximal LAT and ECG morphology according to the statistical analysis of J-wave and VF associations with LAT. Representative ECGs (limb lead III) in the right column were recorded in the same animal at baseline and at 20th and 40th minutes of occlusion. Sp – specificity.

Limitations

In the present investigation, only one locus of coronary occlusion was studied. It is plausible that different occlusion sites should have produced a different size and location of myocardial lesion, which could have resulted in a different electrophysiological and ECG manifestation. The positions and number of intramyocardial leads were limited due to technical reasons and could not ensure a complete “capture” of the ischemic area. This technical limitation at least partly explains the relatively low sensitivity of the LAT parameters. The limited number of animals and endpoints requires cautious interpretation of the data. However, our approach based on continuous multiple-lead potential recordings permitted relating electrophysiological events in the identified ischemic area to simultaneously recorded ECG phenomena that enhanced the quality of obtained results.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that in experimental LAD occlusion model, activation delay in ischemic myocardium is associated with the generation of J-wave pattern. More pronounced LAT prolongation in the IVS expressed in J-wave pattern predicted impending VF. Abnormal depolarization in ischemic myocardium could present a “missing link” between J-wave pattern and arrhythmic risk in conditions of acute myocardial infarction.

Data Availability

The data used in the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Antzelevitch, C. J wave syndromes: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J Electrocardiol 46, 510–518, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.08.006 (2013).

Antzelevitch, C. & Yan, G. X. J wave syndromes. Heart Rhythm 7, 549–558, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.12.006 (2010).

Antzelevitch, C. & Yan, G. X. J-wave syndromes: Brugada and early repolarization syndromes. Heart Rhythm 12, 1852–1866, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.04.014 (2015).

Antzelevitch, C. et al. J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: Emerging concepts and gaps in knowledge. J Arrhythm 32, 315–339, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joa.2016.07.002 (2016).

Haissaguerre, M. et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. New Engl J Med 358, 2016–2023, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa071968 (2008).

Macfarlane, P. W. et al. The Early Repolarization Pattern: A Consensus Paper. J Am Coll Cardiol 66, 470–477, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.033 (2015).

Mahida, S. et al. History and clinical significance of early repolarization syndrome. Heart Rhythm 12, 242–249, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.048 (2015).

Patton, K. K. et al. Electrocardiographic Early Repolarization: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000388 (2016).

Mehta, M., Jain, A. C. & Mehta, A. Early repolarization. Clin Cardiol 22, 59–65 (1999).

Sato, A. et al. Analysis of J waves during myocardial ischaemia. Europace 14, 715–723, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eur323 (2012).

Jastrzebski, M. & Kukla, P. Ischemic J wave: novel risk marker for ventricular fibrillation? Heart Rhythm 6, 829–835, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.036 (2009).

Ali Diab, O., Abdel-Hafez Allam, R. M., Mohamed, H. G., Mohamed, T. R. & Abel-Hafeez Khalid, S. Early repolarization pattern is associated with increased risk of early ventricular arrhythmias during acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 20, 474–480, https://doi.org/10.1111/anec.12249 (2015).

Junttila, M. J. et al. Early repolarization as a predictor of arrhythmic and nonarrhythmic cardiac events in middle-aged subjects. Heart Rhythm 11, 1701–1706, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.05.024 (2014).

Naruse, Y. et al. Early repolarization is an independent predictor of occurrences of ventricular fibrillation in the very early phase of acute myocardial infarction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 5, 506–513, https://doi.org/10.1161/circep.111.966952 (2012).

Rudic, B. et al. Early repolarization pattern is associated with ventricular fibrillation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Heart Rhythm 9, 1295–1300, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.006 (2012).

Demidova, M. M. et al. Transient and rapid QRS-widening associated with a J-wave pattern predicts impending ventricular fibrillation in experimental myocardial infarction. Heart Rhythm 11, 1195–1201, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.048 (2014).

Yan, G. X. & Antzelevitch, C. Cellular basis for the electrocardiographic J wave. Circulation 93, 372–379 (1996).

Koncz, I. et al. Mechanisms underlying the development of the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestations of early repolarization syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol 68, 20–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.012 (2014).

Nakayama, M. et al. J-waves in patients with an acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction who underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention: prevalence, pathogenesis, and clinical implication. Europace 15, 109–115, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eus259 (2013).

Meijborg, V. M. F. et al. Reduced sodium current in the lateral ventricular wall induces inferolateral J-waves. Front Physiol 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00365 (2016).

Bacharova, L. & Halkias, I. The identification of the QRS complex offset in the presence of ST segment deviation. J Electrocardiol 49, 977–979, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2016.07.028 (2016).

Bacharova, L., Szathmary, V. & Mateasik, A. QRS complex and ST segment manifestations of ventricular ischemia: the effect of regional slowing of ventricular activation. J Electrocardiol 46, 497–504, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.08.016 (2013).

Coronel, R. et al. Monophasic action potentials and activation recovery intervals as measures of ventricular action potential duration: Experimental evidence to resolve some controversies. Heart Rhythm 3, 1043–1050, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.05.027 (2006).

Kleber, A. G., Janse, M. J., van Capelle, F. J. & Durrer, D. Mechanism and time course of S-T and T-Q segment changes during acute regional myocardial ischemia in the pig heart determined by extracellular and intracellular recordings. Circul Res 42, 603–613 (1978).

Millar, C. K., Kralios, F. A. & Lux, R. L. Correlation between refractory periods and activation-recovery intervals from electrograms: effects of rate and adrenergic interventions. Circulation 72, 1372–1379 (1985).

Biasco, L. et al. Clinical, Electrocardiographic, Echocardiographic Characteristics and Long-Term Follow-Up of Elite Soccer Players With J-Point Elevation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 6, 1178–1184, https://doi.org/10.1161/circep.113.000434 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Russian Science Foundation [RSF 18-15-00309 to JEA], and the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation [# 20180444 to P.G.P. and # 20180222 to M.M.D.].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.E.A., M.M.D., P.G.P. design; J.E.A., A.O.O., M.A.V. and M.M.D. experiments; J.E.A., A.O.O. and M.A.V. data analysis, J.E.A. drafting article; A.O.O., M.A.V., M.M.D. and P.G.P. critical revision of article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azarov, J.E., Ovechkin, A.O., Vaykshnorayte, M.A. et al. Prolongation of The Activation Time in Ischemic Myocardium is Associated with J-wave Generation in ECG and Ventricular Fibrillation. Sci Rep 9, 12202 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48710-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48710-3

This article is cited by

-

Synthetic recovery of impulse propagation in myocardial infarction via silicon carbide semiconductive nanowires

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.