Abstract

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a key player in synaptic plasticity, and consequently, learning and memory. Because of its fundamental role in numerous neurological functions in the central nervous system, BDNF has utility as a biomarker and drug target for neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. Here, we generated a screening assay to mine inducers of Bdnf transcription in neuronal cells, using primary cultures of cortical cells prepared from a transgenic mouse strain, specifically, Bdnf-Luciferase transgenic (Bdnf-Luc) mice. We identified several active extracts from a library consisting of 120 herbal extracts. In particular, we focused on an active extract prepared from Ginseng Radix (GIN), and found that GIN activated endogenous Bdnf expression via cAMP-response element-binding protein-dependent transcription. Taken together, our current screening assay can be used for validating herbal extracts, food-derived agents, and chemical compounds for their ability to induce Bdnf expression in neurons. This method will be beneficial for screening of candidate drugs for ameliorating symptoms of neurological diseases associated with reduced Bdnf expression in the brain, as well as candidate inhibitors of aging-related cognitive decline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a member of the neurotrophin family, is a key molecule in synaptic plasticity and related phenomena such as long-term memory1. Because of its fundamental role in neural development and function, alterations in BDNF levels are reported in neurological diseases2,3. For example, reduced BDNF levels have been detected in the brains of patients with neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease4, Parkinson’s disease5, and Huntington’s disease6, as well as neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression7 and schizophrenia8. As well as lower BDNF levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from patients with Alzheimer’s disease, reduced CSF levels of BDNF are also associated with progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease9. Indeed, these findings strongly support the notion that BDNF is not only a biomarker but also a potential drug target for these diseases. In support, increased BDNF levels in the hippocampus have been found in post-mortem brains from individuals treated with antidepressant medications10. Further, fingolimod (a sphingoshine 1 phosphate receptor modulator) rescues reduced levels of BDNF in several regions of the brain including the striatum and hippocampus, and ameliorates symptoms in a mouse model of Rett syndrome11. Furukawa-Hibi et al., (2011) have shown that hydrophobic dipeptide leucyl-isoleucine exerts an antidepressant-like effect by inducing BDNF expression12. Moreover, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone, an agonist of the BDNF receptor tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) has been found to have beneficial effects in a number of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease13,14, Parkinson’s disease15, schizophrenia16, and major depression17,18. Together, these reports strongly suggest that identifying inducers of BDNF expression, or activators of TrkB, may contribute to identifying candidate agents and improving symptoms of neurological diseases. However, there is no appropriate method that easily evaluates the ability of appropriate agents to induce BDNF expression in neurons.

Previously, we generated a novel transgenic mouse strain, termed Bdnf-Luciferase transgenic (Bdnf-Luc) mice, to measure and visualise changes in Bdnf expression using firefly luciferase as an imaging probe19. In this transgenic mouse, the firefly luciferase gene was introduced into the translation start site of the mouse Bdnf gene using a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC). Accordingly, transcriptional regulation of Luciferase is under the control of endogenous Bdnf transcription. Therefore, expression of Luciferase reflects that of endogenous Bdnf. Using this approach, we successfully visualised Bdnf transcriptional activation by detecting bioluminescence from each cell in vitro by microscopic time-lapse imaging19,20. We also evaluated changes in Bdnf expression by measuring luciferase activity in a mass of cells.

Here, we generated a high-throughput screening method to screen potential inducers of neuronal Bdnf transcription using primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc mouse cortical cells in a 96-well format. Using this screening assay, we detected a series of Bdnf inducers from neurotransmitter and herbal libraries. We focused on the effect of an active extract prepared from Ginseng Radix (GIN), which was identified from the herbal library, and found to activate endogenous Bdnf expression in cultured cortical cells. Consequently, we show that this extract induces Bdnf expression via cAMP-response element (CRE)-binding protein (CREB)-dependent transcription. Taken together, this screening assay can identify inducers of Bdnf expression in neurons, and may be useful for mining candidates for therapeutic agents of dementia and other BDNF-related neurological diseases as well as inhibitors of aging-related cognitive impairment.

Results

Construction of a screening assay using primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc mouse cortical cells

We have previously demonstrated that induction of Bdnf transcription could be detected by measuring luciferase activity and in vitro bioluminescence imaging using primary cultures of cortical cells prepared from Bdnf-Luc mouse embryos19,20. Here, we used these cultured cortical cells to screen for potential inducers of Bdnf transcription in neurons. We prepared primary cultures of cortical cells from Bdnf-Luc and wild-type mice at embryonic day 16.5 using 96-well culture plates (Fig. 1a,b). To induce membrane depolarization, cultured cells (at 13 days in vitro [DIV]) were treated with high concentrations (25 mM) of KCl for 6 h (Fig. 1b) (which evokes Ca2+ influx into neurons mainly via L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels [L-VDCC] and subsequently activates Bdnf transcription21), then luciferase activity was measured in each well. Compared with controls (5 mM KCl), we detected higher luciferase activity in primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc cortical cells treated with 25 mM KCl (Fig. 1c). In contrast, we barely detected luciferase activity in primary cultures of cortical cells prepared from wild-type mouse embryos in the absence or presence of high KCl concentrations (Fig. 1c).

Construction of a screening assay to examine activity of Bdnf transcription using primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc mouse cortical cells in a 96-well format. (a) Schematic of wild-type Bdnf and Bdnf-Luciferase on a BAC. Detailed information was described previously19,20. (b) Schematic for validating the screening assay system. In 96-well culture plates, Bdnf-Luc mouse (Tg) cortical cells and wild-type (Wt) mouse cortical cells were seeded into wells along lines A–D and lines E–H, respectively. At 13 DIV, cells in wells of columns 2-11 were treated with a high concentration (final 25 mM) of KCl for 6 h. Cells in the wells of columns 1 and 12 were treated with PBS for 6 h. (c) Luciferase activity of each well (left) and the average of luciferase activity (right). Means ± SEM (n = 8 (5 mM KCl), or 40 (25 mM KCl)), ****p < 0.0001 vs. 5 mM KCl (unpaired t-test).

Next, we used commercially available neurotransmitter libraries (ENZO Life Sciences, Inc.; Supplementary Table S1) to examine the ability of each compound to induce Bdnf expression. Cultured cells prepared from Bdnf-Luc mice were treated with each test compound for 6 h, then luciferase activity was measured in each well. We compared luciferase activities of vehicle (DMSO) controls with each compound. Compounds that increased luciferase activity by more than 2-fold were defined as active. Among seven neurotransmitter libraries (dopaminergic, adrenergic, serotonergic, cholinergic, histaminergic, metabotropic glutamatergic, and GABAergic; Supplementary Table S1), active compounds were particularly detected in the dopaminergic library (Fig. 2a). We also identified several active compounds from the adrenergic library (Supplementary Fig. S1a) but rarely from other libraries (Supplementary Fig. S1b–f). In the dopaminergic library, most active compounds were classified as dopamine agonists and dopamine D1 agonists. Meanwhile, active compounds in the adrenergic library were agonists for the adrenaline β receptor. These results corresponded with our previous study on Gs-coupled dopamine D1- and adrenaline β receptor-mediated Bdnf transcription via the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)/calcineurin/CREB-regulated transcriptional coactivator 1 (CRTC1)/CREB pathway19. SKF38393 and isoproterenol have been previously shown to activate Bdnf transcription19, and were included in the dopaminergic and adrenergic libraries used in this study (Fig. 1a [No. 34] and Supplementary Fig. S1a [No. 4], respectively). We chose one compound from the dopaminergic library, A68930 (a selective D1 agonist; Fig. 1a [No. 33]), to determine whether it induced endogenous Bdnf expression in neurons. Using primary cultures of rat cortical cells, we found that endogenous Bdnf mRNA expression levels were increased by A68930 (Fig. 2b). Corresponding with a previous finding that dopamine D1 receptor activation induced Bdnf transcription via the NMDAR/calcineurin pathway19, A68930-induced Bdnf transcription was completely blocked by the NMDAR antagonist D-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) and calcineurin inhibitor FK506 (Fig. 2c). We also chose several compounds, propylnorapomorphine (Fig. 1a [No. 77]), cabergoline (Fig. 1a [No. 50]), and norepinephrine (Supplementary Fig. S1a [No. 78]), from these libraries, and found that they increased endogenous Bdnf mRNA expression levels (Supplementary Fig. S2a–c). In contrast, inactive serotonin (Supplementary Table S1 [Serotonergic library, No. 1] and Supplementary Fig. S1b), only slightly affected mRNA levels (Supplementary Fig. S2d). Focusing on these compounds, we found that changes in endogenous Bdnf mRNA expression levels were strongly correlated with those in luciferase activity (Supplementary Fig. S2e, r = 0.931, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, we identified three active compounds, all of which were GABAA receptor antagonists, from the GABAergic library (Supplementary Fig. S1f [No. 29, 34, and 35]). This corresponds with a previous result showing that a GABAA receptor antagonist blocked inhibitory neurotransmission and evoked neuronal excitation-induced Bdnf transcription in mature neurons22. Taken together, we showed that compounds activating Bdnf transcription in neuronal cells can be screened using primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc cortical cells in a 96-well format.

Screening activators of Bdnf transcription from a dopaminergic library. (a) Representative result obtained using a commercially available dopaminergic library. Each compound was added into Bdnf-Luc cortical cells at 13 DIV at a final concentration of 10, 100, or 1000 nM, and luciferase activity was measured in each well 6 h later. Arrowheads show active compounds (that increased luciferase activity by more than 2-fold). For compound names, see Supplementary Table S1. (b) Changes in Bdnf expression in the presence of dopamine D1 agonist A68930 in primary cultures of rat cortical cells. At 13 DIV, cells were treated with A68930 for 1 h, and then total RNA was prepared for RT-PCR analysis. Means ± SEM (n = 3), ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 vs. 0 nM (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). (c) Effect of APV or FK506 on A68930-induced Bdnf expression in cultured rat cortical cells. APV (200 μM) or FK506 (5 μM) was added 10 min before the addition of A68930 (100 nM). Means ± SEM (n = 3), *p < 0.05 and ****p < 0.0001 vs. DMSO/vehicle, ††††p < 0.0001 vs A68930/vehicle (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test).

Identification of herbal extracts that induce Bdnf expression

Next, we determined whether the current screening assay could be used to identify active crude extracts. We determined the ability of a series of extracts prepared from herbal medicines to induce Bdnf transcription in neurons. We used a library consisting of 120 herbal extracts (Supplementary Table S2). Cultured Bdnf-Luc cortical cells were treated with herbal extracts at a final concentration of 500 μg/mL for 6 h (Fig. 3a), 24 h (Fig. 3b), or 48 h (Fig. 3c), then luciferase activity was measured in each well. We found that five active herbal extracts (Ginseng Radix [Nos. 9 and 36], Zanthoxyli Piperiti Pericarpium [No. 76], Aconiti Radix Processa [No. 94], and Sinomeni Caulis et Rhizoma [No. 112]) increased luciferase activity at 6 h after their addition (Fig. 3a). The number of active extracts increased when cells were treated with each extract for 24 or 48 h. We found eight herbal extracts (Ginseng Radix [Nos. 9 and 36], Polygoni Multiflori Radix [No. 50], Panacis Notoginseng Radix [No. 54], Zanthoxyli Piperiti Pericarpium [No. 76], Rhei Rhizoma [No. 79], Uncariae Uncis Cum Ramulus [No. 80], and Alpiniae Officinari Rhizoma [No. 114]) after 24 h treatment (Fig. 3b), and 11 herbal extracts (Ginseng Radix [Nos. 9 and 36], Amomi Semen [No. 20], Polygoni Multiflori Radix [No. 50], Panacis Notoginseng Radix [No. 54], Zanthoxyli Piperiti Pericarpium [No. 76], Paeoniae Radix Rubra [No. 78], Rhei Rhizoma [No. 79], Uncariae Uncis Cum Ramulus [No. 80], Ephedrae Herba [No. 110], and Alpiniae Officinari Rhizoma [No. 114]) after 48 h treatment (Fig. 3c). We chose a subset of active extracts and confirmed that they significantly increased the endogenous expression of Bdnf mRNA in cultured rat cortical cells (Fig. 4a, Ginseng Radix [No. 36]; and Supplementary Fig. S3a, Zanthoxyli Piperiti Pericarpium [No. 76]; S3b, Ginseng Radix [No. 9]; S3c, Polygoni Multiflori Radix [No. 50]; S3d, Panacis Notoginseng Radix [No. 54]; S3e, Rhei Rhizoma [No. 79]; S3f, Ephedrae Herba [No. 110]; S3g, Alpiniae Officinari Rhizoma [No. 114]; S3h, Sinomeni Caulis et Rhizoma [No. 112]; S3i, Uncariae Uncis Cum Ramulus [No. 80]). We particularly focused on the effect of the extract prepared from Ginseng Radix (GIN), and found that GIN increased levels of endogenous Bdnf mRNA (Fig. 4b), as well as luciferase activity (Fig. 4c), in a dose-dependent manner. Changes in endogenous mRNA levels were strongly correlated with those in luciferase activity (Fig. 4d, r = 0.991, p < 0.01). We also examined the effect of GIN on levels of exon-specific Bdnf mRNA, and found higher induction levels of exon I and exon IV-containing Bdnf mRNA (Fig. 4e), both of which are major components of activity-regulated Bdnf transcription in neurons23,24.

Screening activators of Bdnf transcription from an herbal extract library. Representative results obtained using an herbal extract library consisting of 120 herbal extracts. Each extract was added into Bdnf-Luc cortical cells at 13 DIV at a final concentration of 500 μg/mL. Luciferase activity was measured in each well at 6 h (a), 24 h (b), or 48 h (c) after addition of extract. Means ± SEM (n = 3). Active extracts (that increased Bdnf induction by more than 2-fold) are shown in red.

GIN induces endogenous Bdnf expression in primary cultures of rat cortical cells. (a,b) Time-course (a) and dose-dependency (b) of changes in Bdnf mRNA in the presence of GIN in primary cultures of rat cortical cells. (a) Cells were treated with 500 μg/mL GIN and total RNA was prepared at the indicated time. Means ± SEM (n = 3), **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 vs. water at the same time point (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (b) Cells were treated with different concentrations of GIN, and total RNA was prepared 3 h after treatment. Means ± SEM (n = 3), ****p < 0.0001 vs. 0 μg/mL (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). (c) Bdnf-Luc cortical cells were seeded into a 96-well culture plate and cultured for 13 days. Cells were then treated with different concentrations of GIN, and luciferase activity in each well was measured 6 h after treatment. Means ± SEM (n = 3), *p < 0.05 and ****p < 0.0001 vs. 0 μg/mL (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). (d) Relationship between changes in endogenous Bdnf mRNA expression levels (b) and those in luciferase activity (c) was analysed using a correlation coefficient test. Statistical analysis was performed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient test. (e) The effect of GIN on the expression of 5′ exon-specific Bdnf mRNA in cultured rat cortical cells. Cells were treated with 500 μg/mL GIN and total RNA prepared 3 h after the treatment. Means ± SEM (n = 3), **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 vs. water (unpaired t-test). N.D.: not detected.

As shown in Fig. 3, several extracts reduced luciferase activity. We demonstrated that expression levels of Luciferase and endogenous Bdnf mRNA were reduced after addition of the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (Supplementary Fig. S4a, t1/2 = 5.21 h [Bdnf], 3.67 h [Luciferase]), in cultured Bdnf-Luc cortical cells. In contrast, luciferase activity did not significantly alter after actinomycin D treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4b), suggesting that luciferase protein was stably expressed in the cells. Therefore, reduced luciferase activity by these extracts was not caused by the repression of Bdnf transcription.

We found that some compounds and extracts increased luciferase activity (Figs 2a and 3, Supplementary Fig. 1). To exclude the possibility that increased luciferase activity reflected increased stability of luciferase protein and/or the enhancement of luciferase translation, we used actinomycin D. We found that high concentrations (25 mM) of KCl, norepinephrine, and GIN significantly increased luciferase activity using a screening assay (Supplementary Fig. S4c), which agreed with our earlier results (Figs 1c and 3a, Supplementary Fig. S1a). However, these increases were not observed in the presence of actinomycin D (Supplementary Fig. S4c), suggesting that increased luciferase activity mainly reflected the activation of Bdnf transcription.

Ginsenosides or gintonin do not participate in activation of Bdnf transcription

Next, we sought to identify active compounds from GIN. Ginsenosides are well-known active compounds of Ginseng Radix25. Here, we examined eight types of ginsenosides (specifically, ginsenoside Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, Rf, Rg1, and Rg2), and determined the activity of these compounds using a screening assay. Cultured Bdnf-Luc cortical cells were treated with each ginsenoside for 6 h, then luciferase activity was measured in each well. Although GIN increased luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4c), no individual ginsenoside significantly increased luciferase activity (Fig. 5a), suggesting that individual ginsenosides do not affect Bdnf expression. In contrast, gintonin, a lysophosphatidic acids (LPA)-protein complex mainly containing LPA C18:2, has previously been isolated as an active component of Ginseng Radix26. LPA receptors are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) such as Gi/o, G12/13, Gq/11, and Gs-coupled receptors. We previously reported that stimulation of Gs- and Gq-coupled receptors activates Bdnf transcription via a NMDAR/Ca2+/calcineurin/CRTC1/CREB-dependent pathway19, suggesting that GIN-regulated Bdnf expression may be regulated by gintonin-regulated activation of Gq/11 and/or Gs-coupled LPA receptors. However, the LPA1/2 agonist oleoyl-L-α-lysophosphatidic acid did not affect Bdnf mRNA expression (Fig. 5b). Additionally, the LPA1/3 antagonist, Ki 16425, did not suppress GIN-induced Bdnf expression (Fig. 5c). We also examined whether a series of ginsenosides with or without LPA1/2 agonist could affect Bdnf expression using a screening assay. We chose major ginsenosides, ginsenoside Rb1, Rc, Rd, Re, and Rg1, in an extract of Ginseng Radix (Supplementary Table S2, No. 36, refer to database URL). These ginsenosides and/or LPA1/2 agonist at different concentrations were added to cultured Bdnf-Luc cortical cells for 6 h, then luciferase activity was measured. As shown in Fig. 5d, luciferase activity was not affected by a combination of ginsenosides with or without oleoyl-L-α-lysophosphatidic acid, whereas it was significantly increased by GIN. We also prepared a methanol eluate fraction with enriched ginsenosides27 from a water extract of Ginseng Radix, using a Diaion HP-20 column chromatography (Supplementary Fig. S5a,b). A screening assay showed that luciferase activity was unaffected by this methanol eluate fraction but was increased by water extract (Supplementary Fig. S5c), supporting our finding of a lower effect of individual ginsenoside on luciferase activity (Fig. 5a). Taken together, GIN was shown to activate endogenous Bdnf expression in neurons, yet individual ginsenosides and/or activation of LPA receptors by gintonin does not participate in its induction.

No contribution of ginsenosides or LPA receptors to GIN-induced Bdnf expression. (a) Representative result obtained using a series of ginsenosides consisting of eight types: Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, Rf, Rg1, and Rg2. Each ginsenoside was added into Bdnf-Luc cortical cells at 13 DIV at the indicated concentrations, and luciferase activity was measured in each well 6 h after addition. Means ± SEM (n = 3). (b) Effect of the LPA1/2 receptor agonist, oleoyl-L-α-lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), on Bdnf expression in primary cultures of rat cortical cells. Cells were treated with LPA at the indicated concentrations, and total RNA was prepared 3 h after treatment. Means ± SEM (n = 3). (c) Effect of the LPA1/3 receptor antagonist Ki 16425 on the GIN-induced Bdnf expression. Ki 16425 was added to cells at the indicated concentration 10 min before the addition of GIN (500 μg/mL). Total RNA was prepared 3 h after treatment to examine changes in Bdnf expression by RT-PCR. Means ± SEM (n = 3), ****p < 0.0001 vs. water in the absence or presence of Ki 16425, (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (d) Effect of a combination of ginsenosides and/or LPA on luciferase activity in cultured Bdnf-Luc cortical cells (left). Major ginsenosides (ginsenoside Rb1, Rc, Rd, Re, and Rg1) in GIN (Supplementary Table S2, No. 36 (refer to database URL)) were mixed (final concentrations of each ginsenoside; 10, 50, or 100 μM). Mixed ginsenosides (G-Mix) was added into Bdnf-Luc cortical cells at 13 DIV with or without LPA (final concentration; 0, 10, 50, or 100 μM). GIN was used as a positive control (right). Luciferase activity in each well was measured 6 h after addition. Means ± SEM (n = 6–8). ****p < 0.0001 vs. water (unpaired t-test).

We also used a compound library consisting of 96 types of herbal medicine-derived compounds (Supplementary Table S3), and examined the ability of each compound to induce Bdnf expression in primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc cortical cells. Cultured Bdnf-Luc cortical cells were treated with each compound for 6 h, then luciferase activity was measured in each well. We found that six compounds increased luciferase activity (Supplementary Fig. S6). Among these active compounds, aconitine (No. 1), hypaconitine (No. 56), and mesaconitine (No. 81) are components of Aconiti Radix Processa, the extract of that was identified as active using our screening assay (Fig. 3a [No. 94]). Aconitum alkaloids reportedly bind the α subunit of voltage-dependent Na+ channels and inhibit their inactivation, resulting in the induction of membrane depolarization in neurons28. Considering a previous report showing activity-dependent Bdnf transcription in neurons21, this suggests that the extract prepared from Aconiti Radix Processa may induce activity-dependent Bdnf expression mediated by Aconitum alkaloids.

Intracellular signalling pathways contributing to GIN-induced Bdnf transcription

To identify the signalling pathways involved in GIN-induced Bdnf expression, we investigated the involvement of Ca2+ signalling pathways, which are core pathways of Bdnf regulation in neurons19. Nicardipine, a L-VDCC blocker, and KN93, a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) inhibitor, almost completely blocked GIN extract-induced Bdnf expression (Fig. 6a). Further, APV partially blocked the induction (Fig. 6a). The induction of Bdnf mRNA under GIN treatment was partially prevented by FK506 or mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2) inhibitor U0126, respectively (Fig. 6a).

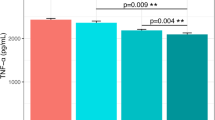

GIN-induced Bdnf transcription via CREB-dependent pathways. (a) Effects of blocking Ca2+ entry sites and Ca2+ signalling inhibitors on GIN-induced Bdnf expression in primary cultures of rat cortical cells. APV (200 μM), nicardipine (Nica, 5 μM), U0126 (20 μM), KN93 (10 μM), or FK506 (5 μM) were added 10 min before the addition of GIN (500 μg/mL). Total RNA was prepared 3 h after treatment to examine changes in Bdnf expression by RT-PCR. Means ± SEM (n = 3), ****p < 0.0001 vs. water, ††††p < 0.0001 vs. DMSO/GIN (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (b) Changes in Bdnf promoter IV (Bdnf-pIV) activity in the presence of GIN. Transfected cortical cells were treated with 500 μg/mL GIN for 6 h, and luciferase activity measured. Means ± SEM (n = 3), **p < 0.01 vs. Wild type/water, ††p < 0.01 vs. Wild type/GIN (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (c,d) (left) Representative images of phosphorylated CREB at serine 133rd (c) or subcellular localization of CRTC1 (d), and (right) percentage of phospho-CREB-positive (c) or nuclear CRTC1-positive (d) neurons. Cultured rat cortical cells were treated with 500 μg/mL GIN for 30 min, then cells were fixed for immunostaining. Scale bar = 20 μm. Means ± SEM (n = 3), ****p < 0.0001 vs. water (unpaired t-test).

Using a luciferase-based promoter assay, we found that GIN activated Bdnf promoter IV (Bdnf-pIV; Fig. 6b), which is a core promoter involved in activity-regulated Bdnf transcription21,29. Furthermore, activation of the promoter was barely observed when CRE (also known as CaRE321,29) on Bdnf-pIV was mutated (Fig. 6b). Taken together with the results obtained from a series of inhibitors (Fig. 6a), CREB-mediated transcription evoked mainly by L-VDCC/Ca2+/CaMKs appears to be involved in the activation of Bdnf transcription by GIN.

We next examined whether CREB-dependent transcription was enhanced by GIN. It is well known that CREB phosphorylation at serine 133rd and nuclear translocation of the CREB coactivator CRTC1 contributes to the activation of CREB-dependent transcription by neuronal activity30. Here, we found that GIN increased the number of neurons with phosphorylated CREB at serine 133rd and nuclear CRTC1 (Fig. 6c,d). These results indicate that GIN activates Bdnf transcription via Ca2+ signal-mediated CREB-dependent transcription.

We also comprehensively analysed gene expression profiles regulated by GIN in cultured rat cortical cells. We chose transcripts with fold-change values of greater than or less than 2 (upregulated and downregulated, respectively). We found that 63 and eight transcripts were significantly upregulated and downregulated, respectively, by treatment of the cells with GIN for 3 h (Supplementary Table S4). We also found that GIN increased the expression of Bdnf and other genes encoding plasticity-related factors such as Nr4a1, Nr4a2, and Homer1 (Supplementary Table S4a)31.

Finally, we examined whether luciferase activity would be measured in other cell types. It has been reported that membrane depolarization induces Ca2+ influx via L-VDCCs and subsequently increases Bdnf expression in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells32,33. Here, we prepared primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells from Bdnf-Luc mice brain using a 96-well culture plate, then cultured cells at 7 DIV were treated with high concentration (25 mM) of KCl for 6 h. We found that luciferase activity was significantly increased by KCl, and the increases were completely abolished in the presence of nicardipine (Supplementary Fig. S7). Thus, it is strongly suggested that inducers of Bdnf expression could be identified in other cell types.

Discussion

Here, we developed a screening assay to identify inducers of Bdnf transcription using primary cultures of cortical cells prepared from Bdnf-Luc mouse embryos. In this transgenic mouse line, the firefly luciferase gene has been introduced into the translation start site of Bdnf using a BAC clone containing the entire mouse Bdnf gene. Therefore, in contrast to the construct in which a truncated promoter region is fused to a reporter gene, luciferase expression from BAC-based Bdnf-Luc is predicted to reflect endogenous Bdnf expression. In fact, our previous study showed that changes in Bdnf expression could be successfully evaluated by measuring luciferase activity as well as a bioluminescence signal in cultured cortical cells19,20. In this study, we successfully detected membrane depolarization-induced increases in luciferase activity, with high signal/noise ratios, using primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc cortical cells in 96 well-format culture plates. Using this method, we identified compounds and herbal extracts from a series of libraries that activated Bdnf transcription in neurons.

We defined compounds that increased luciferase activity by more than 2-fold as active ones, and presume that this threshold is necessary to identify inducers of Bdnf mRNA expression levels in neurons. For example, extracts prepared from Ginseng Radix (No. 9, fold-induction value = 2.10) and Zanthoxyli Piperiti Pericarpium (No. 76, fold-induction value = 2.01) increased endogenous Bdnf mRNA expression levels. In contrast, serotonin, which did not increase luciferase activity (fold-induction value = 1.29 [10 nM], 1.13 [100 nM], 1.32 [1000 nM], respectively), only slightly affected the mRNA levels at any concentrations. However, this threshold was not sufficient for identifying Bdnf inducers. We found that 100 nM propylnorapomorphine and 100 nM cabergoline increased luciferase activity (fold-induction value; 100 nM propylnorapomorphine = 2.96, 100 nM cabergoline = 2.42, respectively), yet these compounds at the same concentration did not significantly affect endogenous Bdnf mRNA expression levels. This might reflect a time lag between changes in endogenous Bdnf transcription and those in luciferase activity. For instance, it has been reported that activation of Bdnf transcription peaked at 1 h after depolarization21 whereas luciferase activity increased gradually and peaked at approximately 7 h after depolarization20. In support of this, time-course changes in luciferase activity after the addition of herbal extracts did not always correspond with those in endogenous Bdnf mRNA expression levels in our study. We suggest that this time lag should be further investigated and that endogenous Bdnf expression levels should be examined to determine if they are increased by active agents obtained in the current screening assay.

The most important aspect of our screening assay is that activation of Bdnf transcription could be evaluated in a primary neuronal culture. Previously, Jaanson et al., (2014) developed a similar screening assay in stable HeLa cell34. They also used a BAC clone and replaced the coding region of the BDNF with the Renilla luciferase-EGFP gene. Accordingly, changes in reporter gene expression were predicted to synchronise with those of endogenous Bdnf expression. However, this strategy enabled screening for regulators of Bdnf expression in HeLa cells, but not in neuronal cells, yet it is questionable whether active compounds identified in HeLa cells have the ability to induce Bdnf expression in neuronal cells. Ishimoto et al., (2012) also developed a novel screening assay to identify CREB activators in HEK293T cell lines35. They also used the same herbal extract library that we used in our study. However, none of the extracts that activated CREB in HEK293T cells could activate Bdnf expression in our current screening assay. Moreover, although the addition of GIN increased CREB phosphorylation in cultured cortical cells, GIN was not observed to activate CREB in the screening assay using HEK293T cells35. These results also suggest that intracellular signalling pathways and cellular responses differ between primary neuronal cells and established cell lines. Alternatively, using our current method, we can screen for inducers of Bdnf expression in neuronal cells and other cell types if primary cultures are prepared from tissues of interest. In support of this, we prepared primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells from Bdnf-Luc mice using a 96-well culture plate, and found that membrane depolarization increased luciferase activity, which agreed with previous reports regarding the activity-dependent Bdnf expression in cultured cerebellar granule cells32,33.

We found that expression levels of Luciferase and endogenous Bdnf mRNA were similarly reduced after the addition of actinomycin D. In contrast, luciferase activity did not significantly alter under the same conditions, suggesting that luciferase protein is stably expressed even if transcription is inhibited. Consequently, it would be difficult to identify negative regulators of Bdnf transcription using our screening assay, because luciferase protein would be stably expressed and luciferase activity would not be easily reduced even if Bdnf transcription is prevented by negative regulators. Nevertheless, our screening assay allows us to identify inducers of Bdnf transcription in neuronal cells. It is also possible that increases in luciferase activity reflect stabilization of luciferase protein and/or enhanced luciferase translation. However, we confirmed that increases in luciferase activity by depolarization, norepinephrine, and GIN were not observed in the presence of actinomycin D, suggesting a contribution of Bdnf transcriptional activation to increases in luciferase activity.

Although our screening assay allows us to identify Bdnf inducers in neurons, it is difficult to clarify how active agents increase Bdnf transcription. In rodents, Bdnf transcription is controlled by nine distinct promoters reported to be regulated by multiple transcription factors that respond to a series of intracellular signalling pathways36,37. Thus, a number of targets exist upstream of Bdnf transcription, although they may not be specific for regulating Bdnf expression. Therefore, it is difficult to construct a screening assay to identify active agents that specifically activate the machinery of Bdnf expression. However, our current assay will be useful for screening agents that are pharmacologically unvalidated compounds or crude extracts, even though the mechanisms of action of these agents on the induction of Bdnf transcription are unclear. In contrast to our screening assay, screenings using genetically engineered biosensors enable the identification of agents that affect specific molecules such as GPCRs. For example, an allosteric biosensor of cAMP has been developed that monitors changes in intracellular signalling evoked by the activation of Gs-coupled GPCRs. Using HEK293 cells expressing this allosteric biosensor, Vedel et al., (2015) showed that β2 adrenergic receptor agonists including salbutamol and metaproterenol increased intracellular cAMP levels in a dose-dependent manner38. However, among β2 adrenergic agonists in the adrenergic library used in this study, only metaproterenol increased luciferase activity. Screening assays focusing on specific targets are useful for identifying active agents with certain mechanisms of action. However, active agents obtained using these methods are not always active for the purpose of identifying Bdnf inducers. Thus, our screening assay is beneficial for the screening of Bdnf inducers in neuronal cells, particularly for identifying unvalidated agents.

Our screening assay identified several herbal extracts that induced Bdnf transcription, and we subsequently confirmed that these extracts induced endogenous Bdnf expression in cultured cortical cells. Although it was difficult to identify negative regulators of Bdnf transcription using our screening assay, we nevertheless identified several extracts that reduced luciferase activity. One possible reason for this is reduction of cell viability based on our use of crude water extracts of herbal medicines, which might include cytotoxic components. Because the luciferase-luciferin reaction that produces bioluminescence is dependent on ATP, a reduction of cell viability would result in lower luciferase activity. In any case, we chose GIN from the active extracts, and demonstrated that it regulates Bdnf transcription via Ca2+ signal-mediated CREB-dependent transcription.

An important point that remains unclear in this study is how GIN can upregulate Bdnf expression in neuronal cells. We attempted to identify active compounds contributing to GIN-induced Bdnf transcription by examining the effect of a series of ginsenosides on Bdnf transcription, yet found that no ginsenoside affected transcription. There are at least two possibilities to explain this: first, multiple ginsenosides may cooperatively participate in the induction of Bdnf expression; or second, other components may contribute to Bdnf induction. We found that a mix of major ginsenosides in GIN did not affect luciferase activity. Moreover, the MeOH eluate fraction of Ginseng Radix with enriched ginsenosides also had no effect on luciferase activity, suggesting that multiple ginsenosides are less likely to affect Bdnf induction. Gintonin, an LPA-protein complex that acts on LPA receptors26, is a candidate for an active component. However, our present results showed that an LPA1/2 agonist had no effect on Bdnf mRNA expression, nor did an LPA1/3 antagonist on GIN-induced Bdnf expression. In this study, we did not examine whether other LPA receptors (Gs-, Gq-, Gi-, or G12/13-coupled GPCRs39) such as LPA4/5 contribute to GIN-induced Bdnf expression. Because our current results also show a major contribution of L-VDCC/Ca2+ and CaMK pathways to GIN-induced Bdnf expression, it is unlikely that Gs- and/or Gq-coupled LPA receptor-mediated Bdnf expression is not involved in the induction. We have previously reported that Gs- or Gq-coupled GPCR-mediated Bdnf induction is mainly dependent on the NMDAR/Ca2+/calcineurin/CRTC1/CREB pathway19. If GIN-induced Bdnf expression is caused by the activation of Gs- and/or Gq-coupled LPA receptors by gintonin, GIN-induced Bdnf expression should be strongly inhibited by NMDAR antagonist or calcineurin inhibitor. We also confirmed that a series of ginsenosides with LPA did not affect Bdnf expression using a screening assay.

Because of known membrane depolarization-induced Bdnf expression in neurons21, we examined K+ concentrations in GIN solution but detected negligible final concentration of K+ in the culture medium (approximately 4 mM K+ in 10 mg/mL GIN solution). We previously reported that high concentrations of KCl-evoked membrane depolarization affected the expression of a large number of transcripts in cultured rat cortical cells40. In contrast, our microarray analysis showed that GIN likely regulates a limited number of transcripts in neurons. Further investigations are therefore necessary to reveal the cellular and molecular basis underlying GIN-induced Bdnf expression in neuronal cells. It is plausible that GIN exerts its neurotrophic effects via the induction of Bdnf expression in neurons. In support of this, GIN showed beneficial effects on neurological diseases including Alzheimer’s disease41 and depression42,43. Further work should examine whether these effects involve BDNF induction. Previous work demonstrated that the administration of ginsenosides such as Rg1 exhibited an antidepressant-like effect in mice44 and ameliorates memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease model mice45. Although these reports show that ginsenoside rescued the reduced expression of BDNF in model animals, it is unclear whether it does so under normal conditions. Our current study is the first to show that GIN, but not active components of GIN such as ginsenoside and gintonin, directly activates Bdnf transcription in neurons. Thus, GIN is expected to have beneficial effects on cognitive and other neuropsychiatric functions in healthy groups as well as those affected by neurological diseases.

Reduced BDNF levels have been reported in some psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases such as depression and Alzheimer’s disease, strongly indicating that BDNF inducers have beneficial effects in these diseases. Further, it has also been reported that higher BDNF expression levels in the brain are associated with slower cognitive decline46. Our current screening assay is useful for identifying Bdnf inducers from crude extracts prepared from herbal medicines and chemical compound libraries, and possibly also from natural foods. Therefore, this assay could be used to develop cognitive stabilisers in the future, which could be consumed as part of a daily diet to suppress cognitive impairment related to aging via increased Bdnf expression in the brain. Taken together, our screening assay could contribute to identifying candidate drugs for improving symptoms in neural diseases as well as protective agents of age-related cognitive decline, at the early phase of drug screening.

Methods

Reagents and libraries

A68930 hydrochloride, (R)-propylnorapomorphine hydrochloride, and cabergoline were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). D-APV, FK506 monohydrate, actinomycin D, L-(−)-norepinephrine (+)-bitartrate salt monohydrate, serotonin, nicardipine, U0126, KN93, oleoyl-L-α-lysophosphatidic acid sodium salt, and Ki 16425 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Neurotransmitter libraries (dopaminergic, adrenergic, serotonergic, cholinergic, histaminergic, metabotropic glutamatergic, and GABAergic) were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY, USA). Ginsenoside kit (Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, Rf, Rg1, and Rg2), used in Fig. 5a, was purchased from Extrasynthese (Genay Cedex, France). Ginsenoside Rb1, Rc, Rd, Re, and Rg1, used in Fig. 5d, were purchased from LKT Laboratories, Inc. (St. Paul, MN, USA). Herbal extract and herbal medicine-derived compound libraries were kindly donated by the Institute of Natural Medicine, University of Toyama (Toyama, Japan). Each herbal extract used in this study was obtained using a standard method described as follows: each herbal medicine (purchased from Tochimoto Tenkaido (Osaka, Japan)) was extracted in water (10-times volume of herbal medicine) at 100 °C for 50 min, evaporated under reduced pressure, and freeze‐dried to obtain a powder extract. Each herbal extract was redissolved in water.

Animals

All animal care and experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the University of Toyama (Authorization No. S-2010 MED-51, A2011PHA-18, and A2014PHA-1) and Takasaki University of Health and Welfare (Authorization No. 1733 and 1809), and were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the University of Toyama and Takasaki University of Health and Welfare. Mice were housed under standard laboratory conditions (12 h-12 h/light-dark cycle, room temperature at 22 ± 2 °C) and had free access to food and water. The generation of Bdnf-Luc mice has been described previously19. Wild-type littermates were used as control animals (Fig. 1b,c).

Primary cultures

Primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc mouse cortical cells were prepared from transgenic mice at embryonic day 16.5, as described previously19. The cerebral cortex was isolated from each embryonic brain, and tissue lysates were briefly prepared from the remaining brain using a passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Next, luciferase activity of each lysate was measured using a luminometer, and transgenic brains were selected on the basis of luciferase activity. Dissociated cells were seeded at 7.6 × 104 cells and cultured in poly-L-lysine-coated 96-well culture plates (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria) with neurobasal medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing B27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 μg/mL gentamicin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 0.5 mM glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In Supplementary Figure S4a, dissociated cells were seeded at 1.8 × 106 cells and cultured in poly-L-lysine-coated 6-well plates (AGC Techno Glass, Shizuoka, Japan) for RT-PCR. Half the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium every 3 days.

Primary cultures of rat cortical cells were prepared from Sprague-Dawley rats at embryonic day 17 (Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan), as described previously19. Dissociated cells were seeded at 1.8 × 106 cells and cultured in poly-L-lysine-coated 6-well plates (AGC Techno Glass) for RT-PCR, or at 8 × 105 cells in poly-L-lysine-coated 12-well plates (AGC Techno Glass) for a reporter assay with neurobasal medium, described above. For immunostaining, cells were seeded at 8 × 105 cells and cultured on poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips of 18 mm in diameter (Matsunami Glass Ind., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) in 12-well plates (AGC Techno Glass). Half the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium every 3 days.

Primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc mouse cerebellar granule cells were prepared from transgenic mice at postnatal day 7, as described previously33. Dissociated cells were seeded at 7.6 × 104 cells and cultured in a poly-L-lysine-coated 96-well culture plate with neurobasal medium, described above. At 3 and 6 DIV, half the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium.

Measuring luciferase activity

Primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc mouse cortical cells at 13 DIV were treated with 25 mM KCl (for 6 h), a series of compounds (for 6 h), or herbal extracts (6, 24, or 48 h). Primary cultures of Bdnf-Luc mouse cerebellar granule cells at 7 DIV were treated with 25 mM KCl (for 6 h). Luciferase activity of each well was measured using the Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) with a Glo-Max Navigator Microplate Luminometer (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. White adhesive seal was added to the bottom of the microplate (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) to make it opaque before the measurement of luciferase activity.

RT-PCR

Total RNA from cultured rat cortical cells was prepared using an ISOSPIN Cell & Tissue RNA kit (Nippongene, Tokyo, Japan). One microgram of purified total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA, as described previously19. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Select Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR thermal profiles included an initial heating at 50 °C for 2 min then at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 45 s, annealing at 57 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. Fold-change values were calculated by the ΔΔCt method to determine relative gene expression. Primer sequences were as follows: rat Gapdh-forward, 5′-ATCGTGGAAGGGCTCATGAC-3′; rat Gapdh-reverse, 5′-TAGCCCAGGATGCCCTTTAGT-3′; rat total Bdnf-forward, 5′-CTGGAGAAAGTCCCGGTATCAA-3′; rat total Bdnf-reverse, 5′-TTATGAACCGCCAGCCAATTCTCTT-3′; rat Bdnf exon I-forward, 5′-CAAACAAGACACATTACCTTCCAGC-3′; rat Bdnf exon II-forward, 5′-AGCCAGCGGATTTGTCCGA-3′; rat Bdnf exon III-forward, 5′-CTCCCCGAGAGTTCCG-3′; rat Bdnf exon IV-forward, 5′-GGAAATATATAGTAAGAGTCTAGAACCTTGG-3′; rat Bdnf exon V-forward, 5′-CTCTGTGTAGTTTCATTGTGTGTTCG-3′; rat Bdnf exon VI-forward, 5′-GACCAGGAGCGTGACAAC-3′; rat Bdnf exon VII-forward, 5′-AAAGGGTCTGCGGAACTCCA-3′; rat Bdnf exon VIII-forward, 5′-GACTGTGCATCCCAGGAGAA-3′; rat Bdnf exon IXA-forward, 5′-GGTCTGAAATTACAAGCAGATGGG-3′; and rat Bdnf exon IX common-reverse, 5′-ACGTTTGCTTCTTTCATGGGCG-3′. To detect each exon-specific Bdnf transcript, a 5′ exon-specific forward primer and exon IX common reverse primer were used. In Supplementary Figure S4a, total RNA from cultured Bdnf-Luc cortical cells was prepared and RT-PCR was performed as described above. Expression levels of Bdnf and Luciferase mRNA were analysed by generating standard curves using cDNA dilution series. Primer sequences were as follows: mouse Bdnf-forward, 5′-AAGGACGCGGACTTGTACAC-3′; mouse Bdnf-reverse, 5′-CGCTAATACTGTCACACACGC-3′; Luciferase-forward, 5′-CGAGTACTTCGAGATGAGCG-3′; and Luciferase-reverse, 5′-CGTTGTAGATGTCGTTAGCTGG-3′.

Microarray analysis

Microarray was performed according to previous studies19,47 using a GeneChip Rat Genome 230 2.0 Array and 3′ IVT Express Kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Primary cultures of rat cortical cells at 13 DIV were treated with 500 μg/mL GIN for 3 h, and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit and QIAshredder (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) for microarray analysis.

Reporter assay

For reporter assays, half the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium at 3, 6, and 10 DIV, then DNA transfection was performed by the calcium/phosphate DNA co-precipitation method at 11 DIV. One hour before the addition of calcium/phosphate/DNA mixture, conditioned medium was removed and kept in a 10% CO2 incubator at 37 °C, and serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with high glucose (Invitrogen, Catalog No.12100046) without antibiotics that had been pre-warmed in a 10% CO2 incubator at 37 °C was added to the cultured cells. Calcium/phosphate/DNA precipitates were prepared by mixing 200 μL of plasmid DNA (16 μg, pGL4.12-Bdnf-pIV:phRL-TK(int−) = 10:1) in 250 mM CaCl2 solution with an equal volume of 2 × HEPES buffered saline (42 mM HEPES [pH 7.03], 274 mM NaCl, 9.5 mM KCl, 2.67 mM Na2HPO4, and 15 mM glucose) and then incubating at room-temperature for 15 min. Next, 95 μL of mixture was added to the cultured cells and incubated in a 10% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 15 min. Cells were then washed twice with serum-free D-MEM with high glucose in the absence of any antibiotics that had been pre-warmed in 10% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Conditioned medium was then returned to the cells. Detailed information on the plasmid DNA for measuring the activity of Bdnf-pIV was described previously19. Two days after DNA transfection, cells were treated with vehicle or GIN extract at a final concentration of 500 μg/mL for 6 h, and firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Firefly luciferase activity was normalised to Renilla luciferase activity.

Immunostaining

At 13 DIV, primary cultures of rat cortical cells were treated with vehicle or GIN extract at a final concentration of 500 μg/mL for 30 min. Immunostaining was then performed using an antibody against microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) (Catalog No. M4403; Sigma-Aldrich) or phosphorylated CREB at serine 133rd (Catalog No. 9198; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), or antiserum against CRTC1 (kindly donated by Dr. Hiroshi Takemori, Graduate School of Engineering, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan), as described previously19. Nuclei were counter-stained with 300 nM 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen). Confocal fluorescent images were obtained using an LSM 700 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The number of MAP2 and phospho-CREB positive neurons or MAP2 and nuclear localized CRTC1 (estimated as described previously19,22) positive neurons were counted, and the percentage of the neurons with phospho-CREB or nuclear localized CRTC1 was calculated.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 7 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Detailed information is shown in each figure legend.

References

Park, H. & Poo, M. M. Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 7–23 (2013).

Angoa-Pérez, M., Anneken, J. H. & Kuhn, D. M. The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the pathophysiology of psychiatric and neurological disorders. J. Psychiatry. Psychiatric. Disord. 1, 252–269 (2017).

Numakawa, T., Odaka, H. & Adachi, N. Actions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the neurogenesis and neuronal function, and its involvement in the pathophysiology of brain diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3650 (2018).

Ferrer, I. et al. BDNF and full-length and truncated TrkB expression in Alzheimer disease. Implications in therapeutic strategies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 729–739 (1999).

Mogi, M. et al. Brain-derived growth factor and nerve growth factor concentrations are decreased in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 270, 45–48 (1999).

Zuccato, C. et al. Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington’s disease. Science 293, 493–498 (2001).

Dwivedi, Y. et al. Altered gene expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and receptor tyrosine kinase B in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 804–815 (2003).

Weickert, C. S. et al. Reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor in prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 8, 592–610 (2003).

Forlenza, O. V. et al. Lower cerebrospinal fluid concentration of brain-derived neurotrophic factor predicts progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 17, 326–332 (2015).

Chen, B., Dowlatshahi, D., MacQueen, G. M., Wang, J. F. & Young, L. T. Increased hippocampal BDNF immunoreactivity in subjects treated with antidepressant medication. Biol. Psychiatry 50, 260–265 (2001).

Deogracias, R. et al. Fingolimod, a sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor modulator, increases BDNF levels and improves symptoms of a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14230–14235 (2012).

Furukawa-Hibi, Y. et al. The hydrophobic dipeptide Leu-Ile inhibits immobility induced by repeated forced swimming via the induction of BDNF. Behav. Brain Res. 220, 271–280 (2011).

Castello, N. A. et al. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone, a small molecule TrkB agonist, improves spatial memory and increases thin spine density in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease-like neuronal loss. PLoS One 9, e91453 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. 7,8-dihydroxyflavone prevents synaptic loss and memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 638–650 (2014).

Jang, S. W. et al. A selective TrkB agonist with potent neurotrophic activities by 7,8-dihydroxyflavone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2687–2692 (2010).

Yang, Y. J. et al. Small-molecule TrkB agonist 7,8-dihydroxyflavone reverses cognitive and synaptic plasticity deficits in a rat model of schizophrenia. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 122, 30–36 (2014).

Zhang, J. C. et al. Antidepressant effects of TrkB ligands on depression-like behavior and dendritic changes in mice after inflammation. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyu077 (2014).

Zhang, M. W., Zhang, S. F., Li, Z. H. & Han, F. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone reverses the depressive symptoms in mouse chronic mild stress. Neurosci. Lett. 635, 33–38 (2016).

Fukuchi, M. et al. Neuromodulatory effect of Gαs- or Gαq-coupled G-protein-coupled receptor on NMDA receptor selectively activates the NMDA receptor/Ca2+/calcineurin/cAMP response element-binding protein-regulated transcriptional coactivator 1 pathway to effectively induce brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in neurons. J. Neurosci. 35, 5606–5624 (2015).

Fukuchi, M. et al. Visualizing changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression using bioluminescence imaging in living mice. Sci. Rep. 7, 4949 (2017).

Tao, X., Finkbeiner, S., Arnold, D. B., Shaywitz, A. J. & Greenberg, M. E. Ca2+ influx regulates BDNF transcription by a CREB family transcription factor-dependent mechanism. Neuron 20, 709–726 (1998).

Fukuchi, M. et al. Excitatory GABA induces BDNF transcription via CRTC1 and phosphorylated CREB-related pathways in immature cortical cells. J. Neurochem. 131, 134–146 (2014).

Tabuchi, A. et al. Differential activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene promoters I and III by Ca2+ signals evoked via L-type voltage-dependent and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17269–17275 (2000).

Tabuchi, A., Sakaya, H., Kisukeda, T., Fushiki, H. & Tsuda, M. Involvement of an upstream stimulatory factor as well as cAMP-responsive element-binding protein in the activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene promoter I. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35920–35931 (2002).

Kiefer, D. & Pantuso, T. Panax ginseng. Am. Fam. Physician. 68, 1539–1542 (2003).

Hwang, S. H. et al. Gintonin, newly identified compounds from ginseng, is novel lysophosphatidic acids-protein complexes and activates G protein-coupled lysophosphatidic acid receptors with high affinity. Mol. Cells 33, 151–162 (2012).

Tran, Q. L. et al. Triterpene saponins from Vietnamese ginseng (Panax vietnamensis) and their hepatocytoprotective activity. J. Nat. Prod. 64, 456–461 (2001).

Ameri, A. The effects of Aconitum alkaloids on the central nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 56, 211–235 (1998).

Tao, X., West, A. E., Chen, W. G., Corfas, G. & Greenberg, M. E. A calcium-responsive transcription factor, CaRF, that regulates neuronal activity-dependent expression of BDNF. Neuron 33, 383–395 (2002).

Nonaka, M. et al. Towards a better understanding of cognitive behaviors regulated by gene expression downstream of activity-dependent transcription factors. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 115, 21–29 (2014).

Fukuchi, M. & Tsuda, M. Convergence of neurotransmissions at synapse on IEG regulation in nucleus. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 22, 1052–1072 (2017).

Condorelli, D. F., Dell’Albani, P., Timmusk, T., Mudò, G. & Belluardo, N. Differential regulation of BDNF and NT-3 mRNA levels in primary cultures of rat cerebellar neurons. Neurochem. Int. 32, 87–91 (1998).

Ichikawa, D., Tabuchi, A., Taoka, A., Tsuchiya, T. & Tsuda, M. Attenuation of cell death mediated by membrane depolarization different from that by exogenous BDNF in cultured mouse cerebellar granule cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 56, 218–226 (1998).

Jaanson, K., Sepp, M., Aid-Pavlidis, T. & Timmusk, T. BAC-based cellular model for screening regulators of BDNF gene transcription. BMC Neurosci. 15, 75 (2014).

Ishimoto, T., Mano, H., Ozawa, T. & Mori, H. Measuring CREB activation using bioluminescent probes that detect KID-KIX interaction in living cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 23, 923–932 (2012).

Aid, T., Kazantseva, A., Piirsoo, M., Palm, K. & Timmusk, T. Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 525–535 (2007).

West, A. E., Pruunsild, P. & Timmusk, T. Neurotrophins: transcription and translation. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 220, 67–100 (2014).

Vedel, L., Bräuner-Osborne, H. & Mathiesen, J. M. A cAMP biosensor-based high-throughput screening assay for identification of Gs-coupled GPCR ligands and phosphodiesterase inhibitors. J. Biomol. Screen. 20, 849–857 (2015).

Yung, Y. C., Stoddard, N. C. & Chun, J. LPA receptor signaling: pharmacology, physiology, and pathophysiology. J. Lipid Res. 55, 1192–1214 (2014).

Fukuchi, M., Kanesaki, K., Takasaki, I., Tabuchi, A. & Tsuda, M. Convergent effects of Ca2+ and cAMP signals on the expression of immediate early genes in neurons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 466, 572–577 (2015).

Kim, H. J. et al. Panax ginseng as an adjuvant treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Ginseng Res. 42, 401–411 (2018).

Lee, S. & Rhee, D. K. Effects of ginseng on stress-related depression, anxiety, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J. Ginseng Res. 41, 589–594 (2017).

Choi, J. H. et al. Panax ginseng exerts antidepressant-like effects by suppressing neuroinflammatory response and upregulating nuclear factor erythroid 2 related factor 2 signaling in the amygdala. J. Ginseng. Res. 42, 107–115 (2018).

Jiang, B. et al. Antidepressant-like effects of ginsenoside Rg1 are due to activation of the BDNF signalling pathway and neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 166, 1872–1887 (2012).

Li, F., Wu, X., Li, J. & Niu, Q. Ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorates hippocampal long-term potentiation and memory in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Mol. Med. Rep. 13, 4904–4910 (2016).

Buchman, A. S. et al. A. Higher brain BDNF gene expression is associated with slower cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology 86, 735–741 (2016).

Takasaki, I. et al. Identification of genetic networks involved in the cell growth arrest and differentiation of a rat astrocyte cell line RCG-12. J. Cell. Biochem. 102, 1472–1485 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Nos. JP25870256 (Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) to M.F.), 16K12894 (Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research to M.F.), and 16H05275 (Grant-in- Aid for Scientific Research (B) to M.F.), Takeda Science Foundation (to M.F.), Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (to M.F.), Hokugin Research Grant (to M.F.), a research grant from Toyama First Bank Foundation (to M.F.), a grant-in-aid for the Cooperative Research Project from the Institute of Natural Medicine at the University of Toyama in 2015 and 2016 (to M.F.), and the Discretionary Funds of the President of the University of Toyama (to M.F.). We thank Dr. Hiroshi Takemori (Graduate School of Engineering, Gifu University) for donating antiserum against CRTC1, and the Institute of Natural Medicine, University of Toyama for donating a library of herbal extracts and herbal medicine-derived compounds. We also appreciate the contribution of members of Prof. Mori’s laboratory (Department of Molecular Neuroscience, Graduate School of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Toyama) to the generation of Bdnf-Luc mice. We thank Rachel James, Ph.D., from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.F. designed the experiments. M.F., Y.O., H.N., A.N., S.M. and Y.N. performed the experiments. H.M. generated Bdnf-Luc mice. I.T. performed the microarray analysis. K.T., M.J., K.W., N.S. and K.K. prepared the series of herbal extracts. M.F., A.T. and M.T. analysed the data. M.F. wrote the manuscript and supervised this study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukuchi, M., Okuno, Y., Nakayama, H. et al. Screening inducers of neuronal BDNF gene transcription using primary cortical cell cultures from BDNF-luciferase transgenic mice. Sci Rep 9, 11833 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48361-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48361-4

This article is cited by

-

The extract based on the Kampo formula daikenchuto (Da Jian Zhong Tang) induces Bdnf expression and has neurotrophic effects in cultured cortical neurons

Journal of Natural Medicines (2023)

-

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in Alzheimer’s disease and its pharmaceutical potential

Translational Neurodegeneration (2022)

-

Visualization of activity-regulated BDNF expression in the living mouse brain using non-invasive near-infrared bioluminescence imaging

Molecular Brain (2020)

-

Born to Protect: Leveraging BDNF Against Cognitive Deficit in Alzheimer’s Disease

CNS Drugs (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.