Abstract

Chronic neuropathic pain constitutes a serious public health problem, but the disease mechanisms are only partially understood. The involvement of different brain regions like the medial prefrontal cortex has already been established, but the comparison of the role of different subregions and layers is still inconclusive. In the current study, we performed patch-clamp recordings followed by anatomical reconstruction of pyramidal cells from different layers of the prelimbic and infralimbic subregions of the medial prefrontal cortex in neuropathic (spared nerve injury, SNI) and control mice. We found that in the prelimbic cortex, layer 2/3 pyramidal cells from SNI mice exhibited increased excitability compared to sham controls, whereas prelimbic layer 5 pyramidal neurons showed reduced excitability. Pyramidal cells in both layer 2/3 and layer 5 of the infralimbic subregion did not change their excitability, but layer 2/3 pyramidal cells displayed increased dendritic length and branching. Our findings support the view that chronic pain is associated with subregion- and layer-specific changes in the medial prefrontal cortex. They therefore provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying the chronification of pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic neuropathic pain constitutes a serious public health problem that affects a large number of individuals worldwide1,2,3,4. The disease mechanisms underlying the chronification of pain are still not completely understood, as is its connection with frequently occurring cognitive and affective impairments5,6. Only a decade ago, research has started to systematically investigate pain related changes of neuronal processing at supraspinal levels, including the brainstem, as well as subcortical and cortical brain regions (for review see7 and8). The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which is primarily known for its prominent role in attention and goal-directed behavior9, provides top-down regulation of sensory and affective processes10, including inhibition of both sensory and affective nociceptive signals by descending projections to various brain and spinal cord regions11,12,13. In both human subjects and rodent models, the mPFC undergoes structural as well as functional changes in chronic pain states14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, which are reflected by cognitive deficits and decreased attention (for review see22). In line with this, attention directed to painful stimuli increases reported pain intensities23 and attention distraction reduces subjective pain intensities in human healthy volunteers24,25, thereby suggesting a strong impact of attention on the chronification of pain.

From an anatomical as well as functional perspective and based on their projection targets, the mPFC can be subdivided into the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the prelimbic (PrL) and the infralimbic cortex (IL)26. The ACC extends rostro-caudally, shows increased activity during acute pain perception as well as during persistent pain conditions27,28, and reduction of ACC activity has been found to relieve pain29. For the remaining mPFC subregions, the majority of studies have so far not separated IL and PrL contributions to functional and structural changes in pain processing15,30,31,32. Also, effects of chronic pain on neuronal populations of different layers of these regions have not yet been investigated systematically.

The current study is therefore the first to systematically dissect the effects of persistent nociceptive activity from the spared nerve injury model of neuropathic pain on pyramidal neurons of layers 2/3 and layer 5 in the PrL and IL mPFC subregions, providing evidence for subregion- and layer-specific alterations of electrophysiological properties and dendritic complexity.

Methods

Animals

All procedures involving animals were carried out in accordance with the Ethics Guidelines of Animal Care (Medical University of Innsbruck), as well as the European Communities Council Directive of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (2010/63/EU), and approved by the Austrian National Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of the Austrian Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung (permit number BMWF-66.011/0087-WF/V/3b/2016). C57BL/6 J mice (Janvier Labs) were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. Animals were maintained at constant room temperature of 24 °C on a 12 h light/dark cycle with lights on from 07:00 to 19:00 and had ad libitum access to autoclaved pelleted food and water. A total of nineteen male adult mice (8–10 weeks old) were used for the experiments. The animals were individually housed for at least 7 days before surgery.

Spared nerve injury (SNI)

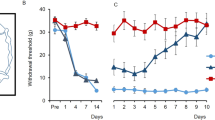

Mice were subjected to SNI as an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain according to the method of33. Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (Ketasol®, 20 mg/ml) and xylazine (Xylasol®, 2 mg/ml) in PBS (5 µl/g body weight, i.p). The sciatic nerve of the left hind leg was exposed at the level of the trifurcation into the sural, tibial, and common peroneal nerves. The tibial and common peroneal nerves were tightly ligated and transected 1–2 mm distal to the ligation, leaving the sural branch intact. Sham-operated mice without nerve transection served as controls as their sciatic nerves were exposed without additional manipulations. The successful induction of mechanical allodynia was confirmed using a dynamic plantar aesthesiometer (Ugo Basile; Supplemental Fig. 1).

Dynamic plantar test

In order to assess hind paw mechanical sensitivity, mice were habituated to a plexi-glass chamber with a metal wire mesh floor for 15 min. The mechanical stimulus was delivered perpendicularly to the lateral side of the plantar surface of the paw (sural nerve innervation territory) by an automated testing device (Dynamic Plantar Aesthesiometer, Ugo Basile). A 0.5 mm steel rod was pushed against the hind paw with ascending force of 0 to 10 g over a period of 10 s at a rate of 1 g/s. The mechanical stimulus automatically stopped when the animal withdrew its hind paw, and the threshold was calculated as an average of three consecutive trials in both paws.

Acute brain slice preparation

Acute coronal brain slices were prepared as previously described34. Briefly, 7 days after surgery the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (Forane®, AbbVie) and decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed and immersed in ice-cold oxygenated protective artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, 95% O2, 5% CO2) containing (in mM): N-methyl-D-glucamine 110, HCl 110, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25, D-glucose 25, MgSO4 10, CaCl2 0.5, Na-ascorbate 1 and Na-pyruvate 2.9, osmolarity: ~310 mOsm/kg, pH adjusted to 7.4 with HCl35. The brains were trimmed with a scalpel blade and glued onto the stage of a vibrating microtome (VT1200S, Leica Microsystems). Coronal slices (thickness 300 µm) containing both the prelimbic and the infralimbic subregions of the prefrontal cortex were cut in oxygenated ice-cold protective aCSF and subsequently incubated at 32–34 °C for 5 minutes. After this recovery period, the slices were transferred to standard oxygenated aCSF containing (in mM): NaCl 125, NaHCO3 25, D-glucose 25, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 2 and MgCl2 1, osmolarity: ~310 mOsm/kg, pH adjusted to 7.4 with HCl36 at room temperature for at least 30 minutes before the electrophysiological recordings.

Electrophysiological recordings and analysis

Sections were visualized in a recording chamber of an upright microscope (BX51WI, Olympus) equipped with differential infrared contrast optics (DIC), and continuously perfused with oxygenated standard aCSF (2–3 ml/min). Synaptic transmission was blocked using CNQX (6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, 5 μM), picrotoxin (5 μM) and D-AP5 (5 μM). Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Science Products) using a flaming micropipette puller (P97, Sutter Instruments) resulting in a pipette resistance of 3–6 MΩ after filling. The pipette solution for current-clamp recordings contained (in mM): 135 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.1 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP and 3–5 mg/ml biocytin (osmolarity: ~295 mOsm/kg, pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH). Recordings were performed at room temperature with an EPC 10 amplifier and PatchMaster software v2x73.1 (HEKA). Data were filtered at 2.9 kHz using a Bessel filter, and the sampling rate ranged from 20 to 50 kHz depending on the protocol applied. Access resistance (Rs) was monitored in the voltage-clamp configuration by analysing capacitive transients during 10 ms square wave depolarizing pulses. Recordings were included only when a GΩ seal formed prior to whole-cell access with a Rs of less than 20 MΩ.

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were obtained from pyramidal cells in layers 2/3 and layer 5 depending on their perpendicular distance from the midline, 100–300 µm and 300–500 µm, respectively. One coronal slice was used per animal and chosen according to the coordinates from37, relative to Bregma, in mm: AP +1.70. Prelimbic and infralimbic subregions were targeted based on their vertical distance from the dorsal end of the midline, 600–1300 µm and 1450–1900 µm, respectively. Data acquisition started 10 min after entering the whole-cell mode allowing sufficient stabilization of the recording. Pyramidal neurons from different layers and subregions were recorded in each of the slices and were distinguished from interneurons by their shape, spiking pattern and action potential width38. In addition, their identity was confirmed by their large apical dendrites, which were visualized through immunohistochemical processing.

None of the neurons showed spontaneous activity, and all parameters were obtained at resting membrane potential (RMP) that was determined by averaging a 1 min recording period at 0 pA in current clamp mode (Supplemental Fig. 2; Supplemental Table 1). Depolarizing current steps (50 ms) with an increment of 10 pA were applied every 3 s via the recording electrode until an action potential (AP) was elicited. Action potential threshold current (IAP) was defined as the minimum amount of current needed to induce the first AP. AP analysis was performed as described previously39. Briefly, five consecutive APs induced by a 50 ms IAP +10 pA depolarizing current were averaged and analyzed using the FitMaster software (HEKA). AP amplitude, afterhyperpolarization (AHP) and AHP time to peak (tAHP) were determined relative to the AP threshold. AP duration was determined at its half-amplitude as AP half-width. The first derivative was used to extract the maximum speed of depolarization (dv/dtmax) and repolarization (dv/dtmin). AP threshold voltage was taken at the point where the depolarization speed first exceeded 10 mV/ms.

Additional biophysical parameters were extracted from voltage responses to 500 ms current pulses at 0.2 Hz ranging from −100 to +500 pA in 20 pA increments. Input resistance (Rin) was obtained by linear fit of the I/V curve from −100 to 0 pA. Membrane time constant (τm) and membrane capacitance (Cm) were obtained by an exponential fit to the voltage response following a −40 mV hyperpolarizing step current40. AP latency of the 1st AP was measured as time from current onset to crossing the voltage threshold of 0 mV. Input-Frequency (I-F) slope was calculated as linear coefficient of the 2nd order polynomial fit of the AP frequency vs. current injection relation. Mean inter-spike interval (ISI) and adaptation ratio (1st ISI/9th ISI) were taken from the first trace with at least 10 APs. Sag ratio (%) was calculated from the current injection that would cause a hyperpolarization of approximately −7.5 mV38 as (Vss − Vmin)/(Vmin − Vrmp), with Vmin being the minimum value reached after the beginning of the current injection, Vss being the voltage at steady-state and Vrmp being the resting membrane potential. After experiments were completed, slices were immersed in a 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixative for at least 24 h prior to subsequent visualization of the filled neurons.

Biocytin visualization

Neuronal morphology was assessed using a diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich) staining protocol as follows: slices were washed three times in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 0.9% NaCl, 0.05 M Tris, pH 7.4) for 10 min each. Subsequently, slices were left for overnight incubation in a 1:100 solution of avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (ABC-Elite) in 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)-TBS at 4 °C. On the next day, sections were washed in TBS and Tris buffer (TB; 0.05 M Tris, pH 7.4), before incubating them in 0.5 mg/ml DAB in TB with Nickel (4 mg/ml). Hydrogen peroxide (0.003%) was added to TB in order to start the peroxidase reaction. Sections were then rinsed with TBS three times and mounted on gelatin-coated slides, and left to air-dry. Finally, they were dehydrated and coverslipped using Eukitt (Marienfeld Lab. Glassware, Germany).

3D reconstruction and Sholl analysis

Biocytin-stained neurons were 3D reconstructed using the NEUROLUCIDA® software (MBF Bioscience). All cells included in the analysis were checked for optimal filling in both apical and basal dendrites. Before tracing, cells were visually inspected and discarded if proximal branches of the dendrites appeared cut. Somata, dendrites and axonal branches were drawn with a 1.3 NA 100x oil objective lens (Olympus BX51). Morphological parameters were analyzed with NEUROEXPLORER® software (MBF Bioscience), including complexity, somatic area, total dendritic length and branching of the dendrites. The area of the cell body was calculated by referring to the boundary of the cell body within a 2D area. To analyze the branch order, the centrifugal ordering system was used as it provides information about both the topological distance as well the amount of branching within a tree. For each neuron, tracing was performed by following the dendrites from the soma to the periphery. Total dendritic length was calculated as the sum of the length of all the branches within a dendritic tree, whereas the mean length was obtained by dividing the total length by the number of primary branches. The complexity was calculated as follows: Complexity = (sum of the terminal orders + number of terminals) * (total dendritic length/number of primary dendrites).

In order to determine dendritic complexity in more detail, Sholl analysis was performed using the NEUROEXPLORER® software. Concentric Sholl rings were set at 10 µm intervals from the soma. The analysis was based on calculating the number of intersections and dendritic length per Sholl ring interval.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analyses, GraphPad Prism 7 (two-tailed Student’s t-test, 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test) and Origin 9 (polynomial curve fitting), were used as applicable. The level of statistical significance was predefined at p < 0.05.

Results

As a first step, we confirmed SNI induced mechanical hypersensitivity in the operated paw by measuring mechanical withdrawal thresholds at baseline and 7 days after surgery. As expected, SNI operated mice exhibited a significant reduction in the paw withdrawal threshold of the operated paw compared to sham controls as well as compared to baseline measurements (2-way RM ANOVA, p < 0.001; Supplemental Fig. 1). In addition, the withdrawal threshold of the non-operated (contralateral) paw was unaltered (2-way RM ANOVA, p > 0.05; Supplemental Fig. 1).

In order to investigate whether the spared nerve injury (SNI) mouse model induces layer specific and subregion specific electrophysiological and morphological changes in pyramidal cells of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), we performed whole-cell patch clamp recordings and subsequent morphological analyses in a subset of recorded neurons 7 days after surgery. The prelimbic (PrL) cortex is set along the midline and is bordered dorsally by the anterior cingulate cortex and ventrally by the infralimbic (IL) cortex. In this study we investigated layer 2/3 and layer 5 pyramidal cells of both PrL and IL cortical areas.

Recordings were performed in the presence of blockers of fast synaptic transmission (5 µM CNQX, 5 µM D-AP5, 5 µM picrotoxin) and were included in the analysis only if the resting membrane potential was stable and below −60 mV, and if pyramidal cell like morphology was confirmed. Experimenters were blind to the treatment condition.

SNI increases the excitability of layer 2/3 pyramidal cells of the prelimbic (PrL) cortex

In order to investigate the main input region of the prelimbic (PrL) prefrontal cortex, we first targeted PrL layer 2/3 (L2/3) pyramidal cells of sham and SNI treated mice by mapping the landmarks of the coronal slices to the mouse brain stereotaxic atlas (37; Fig. 1a). By measuring the distance from the dorsal end of the midline, we ensured the same localization of recorded neurons between the two treatment groups (Table 1; x/y coordinates: sham 917.64 ± 28.98/222.14 ± 5.27 µm vs. SNI 912.33 ± 24.81/230.87 ± 6.89 µm; Student’s t-test, px = 0.89/py = 0.33). Whole-cell recordings showed that passive membrane properties of PrL L2/3 pyramidal neurons differed between SNI and sham-operated mice (Fig. 1d; Table 1). By measuring the resting membrane potential, we observed a more depolarized state of L2/3 pyramidal neurons after SNI, but not sham treatment (SNI −74.37 ± 0.99 mV vs. sham −77.08 ± 0.80 mV; Student’s t test, p = 0.04). Neurons from SNI mice showed a higher input resistance (SNI: 182.44 ± 16.07 MΩ; sham: 140.96 ± 10.32 MΩ) compared to the sham group (Student’s t-test, p = 0.04). The membrane time constant (τm) was also significantly higher in SNI mice compared to sham (SNI 29.14 ± 2.52 ms vs. sham 22.33 ± 1.56 ms; Student’s t-test, p = 0.03). Correspondingly, we observed a trend towards increased firing rate in response to 500 ms depolarizing current injection in the SNI group (Fig. 1e; Table 1; I-F slope (pA/100 Hz): SNI 13.94 ± 0.64 vs. sham 12.45 ± 0.52; Student’s t-test, p = 0.08). AP properties were similar for both groups (Table 1). The firing pattern in both groups exhibited strong adaptation as indicated by the ratio of the first and last interspike interval obtained from the first trace with at least 10 APs (ISI1/ISIn: SNI 0.33 ± 0.02 vs. sham 0.31 ± 0.02; Student’s t-test, p > 0.05). The voltage sag ratio indicative for the activation of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide–gated (HCN) channels in response to a hyperpolarizing current injection of ~−7.5 mV was similar in both groups (sham: 4.55 ± 0.25%; SNI: 4.27 ± 0.27%, Student’s t-test, p > 0.05) and consistent with low HCN channel expression in L2/3 pyramidal cells compared to deeper cortical layers38.

Firing rate and Sholl analysis of layer 2/3 pyramidal cells in the prelimbic (PrL) cortex of SNI and sham mice. (a) Location of recorded neurons in the hemisphere contralateral to the injured paw. Recordings were performed in the presence of blockers of fast synaptic transmission (5 µM CNQX, 5 µM D-AP5 and 5 µM picrotoxin). Inset shows DAB stained, biocytin filled neurons in the targeted region. (b) Representative examples of reconstructed L2/3 PrL pyramidal cells. (c) Representative electrophysiological profile of L2/3 PrL pyramidal neurons in the SNI (left) and sham (right) group. Top, firing pattern when a minimum of 10 action potentials was elicited in response to the corresponding current step. Below, adaptation ratios from 1st to the n-1st interspike interval relative to the last (nth) presented as a heat map. Bottom, response to hyperpolarizing current injections that would be used to calculate the input resistance and the voltage sag ratio. (d) Column graphs showing the resting membrane potential and input resistance of the two groups (*p < 0.05, Student’s t-test). (e) Firing rate as a function of injected current in SNI mice compared to sham controls (p > 0.05, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures). Input-frequency slope calculated as a linear coefficient of the polynomial fitting of the curves (p > 0.05, Student’s t-test). (f) Sholl analysis of the reconstructed apical dendrites in SNI and sham treated mice (p > 0.05, 2-way ANOVA). (g) Sholl analysis of the basal dendrites shows an increase in the number of intersections and length per distance from soma in SNI mice (p < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA).

Anatomical reconstruction of 10 recorded pyramidal neurons per group showed no apparent differences in the length or complexity of basal and apical dendrites (Table 1). Furthermore, consistent with the unaltered membrane capacitance (SNI 165.37 ± 8.12 pF vs. sham 171.89 ± 10.22 pF; Student’s t test, p > 0.05), there was no difference in the surface area of the somata between the two groups (SNI 102.10 ± 6.23 µm2 vs. sham 120.98 ± 9.65 µm2; Student’s t-test, p > 0.05). However, more detailed Sholl analysis41 revealed that basal dendrites of L2/3 pyramidal neurons from SNI treated mice had a higher number of intersections (Fig. 1g; 2-way ANOVA, treatment effect, p = 0.0059) and an increased length per distance compared to sham animals (Fig. 1g; 2-way ANOVA, treatment effect, p = 0.027). In contrast, in the apical dendrites the number of intersections and the dendritic length was similar between the two groups of mice (Fig. 1f; 2-way ANOVA, treatment effect, p > 0.05). Taken together, these findings suggest that neuropathic pain leads to a fine structural remodeling of the basal dendritic arbors of PrL L2/3 pyramidal neurons.

SNI reduces the firing rate of prelimbic layer 5 pyramidal neurons

We next tested if pyramidal neurons in L5, the main output layer of the neocortex, were altered in SNI treated mice 7 days after surgery. In recordings from PrL L5 pyramidal cells at the same relative coordinates in sham and SNI mice (Table 2; x/y coordinates: sham 933.61 ± 25.52/427.55 ± 6.86 µm vs. SNI 888.11 ± 25.85/425.96 ± 10.04 µm; Student’s t-test, px = 0.22/py = 0.90) we found no difference in passive membrane properties between the two treatment groups (Table 2; Fig. 2d). The resting membrane potential was −67.29 ± 0.45 mV for sham and −68.06 ± 0.58 mV for SNI (Student’s t-test, p = 0.31). Correspondingly, input resistance (SNI 179.50 ± 13.61 MΩ vs. sham 167.62 ± 13.52 MΩ; Student’s t-test, p = 0.55) and AP parameters were similar in both groups (Table 2). Lower firing rates were detected in neurons of the SNI group in response to 500 ms depolarizing current injections (Fig. 2e; repeated measures 2-way ANOVA, treatment effect, p = 0.033). Consistently, the I-F linear slope was reduced in the SNI group following a polynomial fitting of the I-F relationship (SNI 13.47 ± 0.35 Hz/100 pA vs. sham 14.69 ± 0.35 Hz/100 pA; Student’s t test, p = 0.02). Overall, PrL L5 pyramidal neurons exhibited a prominent and similar voltage sag of 16.47 ± 1.60% in sham and 14.99 ± 1.76% in SNI.

Firing rate and Sholl analysis of layer 5 pyramidal cells in the prelimbic (PrL) cortex of SNI and sham mice. (a) Location of recorded neurons in the hemisphere contralateral to the injured paw. Recordings were performed in the presence of blockers of fast synaptic transmission (5 µM CNQX, 5 µM D-AP5 and 5 µM picrotoxin). Inset shows DAB stained, biocytin filled neurons in the targeted region. (b) Representative examples of reconstructed L5 PrL pyramidal cells. (c) Representative electrophysiological profile of L5 PrL pyramidal neurons in the SNI (left) and sham (right) group. Top, firing pattern when a minimum of 10 action potentials was elicited in response to the corresponding current step. Below, adaptation ratios from 1st to the n-1st interspike interval relative to the last (nth) presented as a heat map. Bottom, response to hyperpolarizing current injections to calculate input resistance and voltage sag ratio. (d) Bar graphs of the resting membrane potential and the input resistance of the two groups (p > 0.05, Student’s t-test). (e) Firing rate as a function of injected current showing a reduced discharge in SNI mice compared to sham controls (p < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures). Input-frequency slope calculated as a linear coefficient of the polynomial fitting of the curves (*p < 0.05, Student’s t-test). (f) Sholl analysis of reconstructed apical dendrites shows an increase in the number of intersections and length per distance from soma in SNI mice (p < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA). (g) Sholl analysis of the basal dendrites shows an increase in the number of intersections and length per distance from soma in SNI mice (p < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA).

Even though none of the primary morphological parameters of the dendritic tree of L5 pyramidal cells differed between SNI and sham animals (Table 1), Sholl analysis revealed a significant increase in both apical and basal dendrites in the length per distance (2-way ANOVA, treatment effect: apical dendrites, p < 0.002; basal dendrites, p < 0.001) as well as number of intersections (2-way ANOVA, treatment effect: apical dendrites, p < 0.001; basal dendrites, p < 0.001) in SNI mice (Fig. 2f,g).

SNI extends the dendritic arbor of infralimbic layer 2/3 pyramidal cells without altering their biophysical properties

In agreement with previous studies in mouse models of neuropathy our data indicate that the PrL cortex undergoes functional and morphological changes already 7 days after surgery42,43. However, we observed that the two subregions of the mPFC, namely the PrL and the IL, were robustly different in terms of their physiological parameters in the sham group, with the IL neurons of both L2/3 and L5 showing higher excitability as well as lower membrane capacitance (Supplemental Table 2). We recorded from L2/3 pyramidal neurons of the IL cortex that were equally distributed between the treatment groups (Table 3; x/y coordinates: sham 1679.26 ± 24.19/212.53 ± 5.32 µm vs. SNI 1646.73 ± 25.83/219.83 ± 5.53 µm; Student’s t-test, px = 0.39/py = 0.37). In overt contrast to the PrL, both passive and active membrane properties of neurons were similar in SNI and control mice (Fig. 3d,e; Table 3). Conversely, morphological analysis revealed striking differences of IL L2/3 pyramidal cells between the two groups. Apical dendrites in SNI mice were significantly longer (Table 3; SNI: 802.39 ± 68.37 µm vs. sham: 592.80 ± 60.66 µm; Student’s t-test, p = 0.04) and showed higher complexity (Table 3; SNI: 39338.6 ± 6253.1 vs. sham: 19301.0 ± 3938.2; Student’s t-test, p = 0.02). For the basal dendrites in the SNI group only a trend towards an increased length (SNI: 180.67 ± 30.39 µm vs. sham: 109.24 ± 12.84 µm; Student’s t-test, p = 0.055) and complexity (SNI: 9103.0 ± 2798.1 vs. sham: 3491.2 ± 1109.4; Student’s t-test, p = 0.09) was observed. Consistently, Sholl analysis revealed a higher number of intersections (2-way ANOVA, treatment effect: apical dendrites, p < 0.001; basal dendrites, p < 0.001) and increased length (2-way ANOVA, treatment effect: apical dendrites, p < 0.001; basal dendrites, p = 0.002) of both the apical and basal dendrites compared to sham (Fig. 3f,g).

Firing rate and Sholl analysis of layer 2/3 pyramidal cells in the infralimbic (IL) cortex of SNI and sham mice. (a) Location of recorded neurons in the hemisphere contralateral to the injured paw. Recordings were performed in the presence of blockers of fast synaptic transmission (5 µM CNQX, 5 µM D-AP5 and 5 µM picrotoxin). Inset shows DAB stained, biocytin filled neurons in the targeted region. (b) Representative examples of L2/3 IL pyramidal cells. (c) Representative electrophysiological profile of L2/3 IL pyramidal neurons in the SNI (left) and sham (right) group. Top, firing pattern when a minimum of 10 action potentials was elicited in response to the corresponding current step. Underneath, adaptation ratios from 1st to the n-1st interspike interval relative to the last (nth) presented as a heat map. Bottom, response to hyperpolarizing current injections to calculate the input resistance and the voltage sag ratio. (d) Column graphs showing the resting membrane potential and input resistance of the two groups (p > 0.05, Student’s t-test). (e) Firing rate as a function of injected current in SNI mice compared to sham controls (p > 0.05, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures). Input-frequency slope calculated as a linear coefficient of the polynomial fitting of the curves (p > 0.05, Student’s t-test). (f) Sholl analysis of the reconstructed apical dendrites shows an increase in the number of intersections and length per distance from soma in SNI mice (p < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA). (g) Sholl analysis of basal dendrites shows an increase in the number of intersections and length per distance from soma in SNI mice (p < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA).

SNI does not affect the morphological and physiological features of infralimbic layer 5 pyramidal cells

Finally, we tested L5 pyramidal cells of the IL cortex (Table 4; x/y coordinates: sham 1679.26 ± 24.19/212.53 ± 5.32 µm vs. SNI 1646.73 ± 25.83/219.83 ± 5.53 µm; Student’s t-test, px = 0.39/py = 0.37). Resting membrane potential (SNI: −66.91 ± 0.63 mV vs. sham: −66.31 ± 0.64 mV; Student’s t-test, p = 0.44) and input resistance (sham: 179.77 ± 10.98 MΩ vs. SNI: 188.70 ± 6.92 MΩ; Student’s t-test, p = 0.49) were similar in both groups (Fig. 4d). SNI surgery did not alter the AP firing rate (Fig. 4e; repeated measures 2-way ANOVA, p > 0.05) or any of the additional AP parameters (Table 4).

Firing rate and Sholl analysis of layer 5 pyramidal cells in the infralimbic (IL) cortex of SNI and sham mice. (a) Location of recorded neurons in the hemisphere contralateral to the injured paw. Recordings were performed in the presence of blockers of fast synaptic transmission (5 µM CNQX, 5 µM D-AP5 and 5 µM picrotoxin). Inset shows DAB stained, biocytin filled neurons in the targeted region. (b) Representative examples of L5 IL pyramidal cells. (c) Representative electrophysiological profile of L5 IL pyramidal neurons in the SNI (left) and sham (right) group. Top, firing pattern when a minimum of 10 action potentials was elicited in response to the corresponding current step. Below, adaptation ratios from 1st to the n-1st interspike interval relative to the last (nth) presented as a heat map. Bottom, response to hyperpolarizing current injections to calculate input resistance and voltage sag ratio. (d) Column graphs showing the resting membrane potential and input resistance of the two groups (p > 0.05, Student’s t-test). (e) Comparable firing rate as a function of injected current between the two groups (p > 0.05, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures). Input-frequency slope calculated as a linear coefficient of the polynomial fitting of the curves (p > 0.05, Student’s t-test). (f,g) Sholl analysis of the reconstructed apical and basal dendrites in SNI and sham treated mice (p > 0.05, 2-way ANOVA).

Correspondingly, the morphology of the apical and basal dendrites of L5 cells was similar between SNI and sham treated mice (Table 4). Sholl analysis, likewise, showed similar numbers of intersections (2-way ANOVA, p > 0.05) and branching (2-way ANOVA, p > 0.05) in both apical and basal dendrites of L5 pyramidal neurons of the two groups (Fig. 4f,g).

Discussion

In the current study, we used a combined electrophysiological and morphological approach to assess alterations of mPFC pyramidal neurons induced by neuropathic nerve injury with a special focus on subregional and laminar specificity. We report a differential modulation of neuronal excitability in L2/3 and L5 of the PrL following SNI. In contrast, IL pyramidal cells were functionally unaltered in all layers investigated. Anatomical reconstruction of the recorded neurons showed that neuropathic pain was associated with increased dendritic length and complexity of pyramidal cells in L2/3 of the IL. Limited structural rearrangements were also revealed in L2/3 and L5 neurons of the PrL that were, however, only detected by more detailed analysis of their morphological characteristics.

Our results build on previous studies showing that stimulation of deeper layers of the mPFC alleviates both the sensory and affective components of pain and that their inhibition worsens nocifensive and motivational behaviour13,43,44,45,46,47. Specifically, we found that PrL L2/3 pyramidal neurons showed an increased input resistance and a more depolarized resting membrane potential 7 days after SNI treatment, indicative of increased excitability. These findings are in line with Cordeiro Matos, et al.32 reporting higher input resistance and neuronal activity in superficial layers of the mPFC of SNI treated rats three weeks after surgery. Persistent pain in SNI treated rats 7 days after surgery is associated with increased synaptic signalling in L2/3 pyramidal neurons due to an increase in the NMDA/AMPA ratio15. Moreover, overexpression of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B in the mPFC increases responsiveness to inflammatory stimuli48.

However, SNI induced effects on passive and active membrane properties of L2/3 pyramidal cells are controversial and this may be related to pooling neuronal recordings from different neighbouring regions that show small but important differences, such as more dorsal regions corresponding to ACC rather than PrL15,30,32.

In contrast to pyramidal cells in the superficial PrL cortex, deep PrL L5 pyramidal neurons of SNI mice generated significantly lower firing rates in response to suprathreshold depolarizing current injections compared to controls. This is in line with previous studies reporting reduced excitability and action potential discharge activity of L5 PrL neurons within the mPFC in the SNI model of neuropathic pain42,43. A possible explanation for functional deactivation of the PrL cortex in neuropathic pain could be a reduction in glutamatergic currents in L5 pyramidal neurons of the mPFC of SNI rats30. More likely, local or amygdala driven feed-forward inhibition may account for neuron deactivation as documented in rat models of arthritis and SNI43. These in vitro data are corroborated by an in vivo study demonstrating reduced basal spontaneous as well as pain-evoked activity in the PrL in a rat model of persistent inflammatory pain49.

We also observed important differential effects of SNI on pyramidal cell excitability between the PrL and IL cortical regions (Supplemental Table 2). This could be explained by differential inputs that PrL and IL cortices receive from subcortical areas, in particular the basolateral amygdala50, which is reflected by the different roles of these areas in fear learning and memory51,52,53. Previous studies mainly focused on the ACC and the PrL cortices, since experimental lesions within these areas reduced mechanical hypersensitivity as well as conditioned-place aversion, whereas lesions of the IL cortex did not54,55.

So far, electrophysiological studies investigating the role of IL cortex in pain processing have not been conclusive. We demonstrate that functional properties of pyramidal cells in both superficial and deep cortical layers in the IL cortex are unaltered in neuropathic mice, which is in line with Cheriyan and Sheets42. Other studies, however, report changes in the IL, including loss of parvalbumin expressing (PV+) neurons and reduction of axon initial segment length in L5/6 neurons of the IL but not PrL three weeks after SNI injury56.

Apart from functional changes, pyramidal cells in superficial layers of the mPFC were shown to undergo morphological structural changes following SNI15. Our findings are consistent with this report, also demonstrating increased dendritic branching only in the basal but not the apical dendrites of PrL L2/3 pyramidal cells in SNI mice. In addition, the apical and basal dendrites of L5 PrL pyramidal cells showed a moderately increased branching after SNI, but no significant changes in total dendritic length and complexity. These findings appear at odds with a recent study reporting reduced length and branching of apical dendrites, along with reduced glutamatergic currents, in the mPFC of SNI rats30. Kelly, et al.30 also reported an increased input resistance and a reduced membrane capacitance of these cells that we could not observe in our experiments. Although species-specific differences cannot be ruled out, the reasons for this discrepancy are at present unclear and warrant further investigations.

Pyramidal neurons in deeper cortical layers of the IL were morphologically unaltered by SNI 7 days after surgery. This supports our electrophysiological data, as we observed no difference in the excitability of the recorded neurons in this layer. However, superficial pyramidal cells of the IL showed increased dendritic branching at both basal and the apical dendrites. With L2/3 representing the main mPFC input region, this increased dendritic complexity could represent a compensatory mechanism in response to a reduced glutamatergic input from the ventral hippocampus and mediodorsal thalamus57. That neuropathic pain leads to changes in dendritic branching correlates well with the upregulation of genes important for axonal guidance and maturation of dendritic spines, observed in the mPFC of SNI mice58.

The reasons for subregion- and layer-specific changes can be manifold. One possibility may be alterations in the activity of different local inhibitory circuits. Different GABAergic interneuron types differ in how they synapse on projection neurons, and thereby in how they control excitability and action potential integration before an output is generated59. They are distributed in a specific manner across different cortical layers60. For example, somatostatin (SOM+) and PV+ interneurons in L5 of the somatosensory cortex show reduced activity in the SNI mouse model, whereas vasointestinal polypeptide-expressing (VIP+) interneurons exhibit increased activity61. Consistently, the activity of PV+ interneurons drives the increase in the inhibitory GABAergic tone in PrL L5 of SNI operated mice43, while the excitation profile of PrL L2/3 PV+ interneurons and SOM+ interneurons across both layers is unaltered in the chronic constriction injury mouse model42.

Alternatively, altered input to the mPFC may be sufficient to explain the subregion- and layer-specific differences. Terminals from the ventral hippocampus are distributed unevenly in the mPFC, with more terminals ending in ventral regions57, and the basolateral amygdala (BLA) projecting to layer 2 neurons of the PrL rather than the IL50. Interestingly, BLA projections preferentially target neurons projecting to the periaquaeductal grey, the main descending pain control hub50. This top-down control of the descending pain-pathway has also been implicated as a possible target contributing to the chronification of pain, with facilitation of either direct ACC-to-spinal cord62 or sensory cortex-to-spinal cord63 projections. Therefore, modulation of specific types of interneurons limited to specific mPFC subregions and layer specific projections from relevant pain processing brain regions could be responsible for the currently observed differences.

Also, it should be noted that the changed electrophysiological and morphological properties observed in the different layers and subregions of the mPFC might vary between different timepoints after nerve injury, and might therefore be associated with different stages of neuropathy and pain chronification.

Studies on humans and rodents strongly suggest that males and females show different sensitivity to pain and differences in peripheral or spinal processing of painful stimuli64,65. Women show stronger activation of the mPFC than men in response to subthreshold and strong painful stimuli, which could be linked to increased self-related attention in response to pain66 and only female mice show differential pERK activation in mPFC in a partial nerve ligation model67. In the current investigation all recordings were performed in male mice since male SNI mice are significantly more impaired in a set-shifting task for prefrontal cortex dysfunction than female mice56. However, additional studies are required to obtain mechanistic insight into sex-specific circuits for the processing of nociceptive stimuli in the mPFC.

In the present study we provide the first systematic investigation of subregion and layer specific neuronal changes occurring in the PrL and IL cortices of neuropathic mice, thereby providing new insights into mPFC neuronal reorganization associated with the chronification of pain.

In conclusion, our results support the view that neuropathic pain results from region- and layer-specific functional as well as structural changes of the mPFC. The dissection of these complex alterations may contribute to a better understanding of the widespread plasticity events occurring in different brain regions as a consequence of long-lasting pain, and possibly to the identification of novel strategies for the development of more effective, mechanism-targeted treatments.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Breivik, H., Collett, B., Ventafridda, V., Cohen, R. & Gallacher, D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 10, 287–333, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009 (2006).

Macfarlane, G. J., Mcbeth, J. & Jones, G. T. In Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain (eds Mcmahon, S. B., Koltzenburg, M., Tracey, I. & Turk, D.) 232–247 (Elsevier, Saunders, 2013).

van der Windt, D. A. et al. Impact of physical symptoms on perceived health in the community. J Psychosom Res 64, 265–274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.003 (2008).

Murray, C. J. & Lopez, A. D. Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med 369, 448–457, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1201534 (2013).

Workman, E. A., Hubbard, J. R. & Felker, B. L. Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders and Predictors of Pain Management Program Success in Patients With Chronic Pain. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 4, 137–140 (2002).

Radat, F., Margot-Duclot, A. & Attal, N. Psychiatric co-morbidities in patients with chronic peripheral neuropathic pain: a multicentre cohort study. Eur J Pain 17, 1547–1557, https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00334.x (2013).

Schaible, H. G. Peripheral and central mechanisms of pain generation. Handb Exp Pharmacol, 3–28 (2007).

Ossipov, M. H., Dussor, G. O. & Porreca, F. Central modulation of pain. J Clin Invest 120, 3779–3787, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI43766 (2010).

Bloem, B., Poorthuis, R. B. & Mansvelder, H. D. Cholinergic modulation of the medial prefrontal cortex: the role of nicotinic receptors in attention and regulation of neuronal activity. Front Neural Circuits 8, 17, https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2014.00017 (2014).

Salzman, C. D. & Fusi, S. Emotion, cognition, and mental state representation in amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 33, 173–202, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135256 (2010).

Fields, H. L., Bry, J., Hentall, I. & Zorman, G. The activity of neurons in the rostral medulla of the rat during withdrawal from noxious heat. J Neurosci 3, 2545–2552 (1983).

Ji, G. & Neugebauer, V. CB1 augments mGluR5 function in medial prefrontal cortical neurons to inhibit amygdala hyperactivity in an arthritis pain model. Eur J Neurosci 39, 455–466, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.12432 (2014).

Lee, M. et al. Activation of corticostriatal circuitry relieves chronic neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 35, 5247–5259, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3494-14.2015 (2015).

Apkarian, A. V. et al. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. J Neurosci 24, 10410–10415, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2541-04.2004 (2004).

Metz, A. E., Yau, H. J., Centeno, M. V., Apkarian, A. V. & Martina, M. Morphological and functional reorganization of rat medial prefrontal cortex in neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 2423–2428, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0809897106 (2009).

Ji, G. et al. Cognitive impairment in pain through amygdala-driven prefrontal cortical deactivation. J Neurosci 30, 5451–5464, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0225-10.2010 (2010).

Ji, G. & Neugebauer, V. Pain-related deactivation of medial prefrontal cortical neurons involves mGluR1 and GABA(A) receptors. J Neurophysiol 106, 2642–2652, https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00461.2011 (2011).

Moayedi, M. et al. Contribution of chronic pain and neuroticism to abnormal forebrain gray matter in patients with temporomandibular disorder. Neuroimage 55, 277–286, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.013 (2011).

Obara, I. et al. Homers at the Interface between Reward and Pain. Front Psychiatry 4, 39, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00039 (2013).

Hung, K. L., Wang, S. J., Wang, Y. C., Chiang, T. R. & Wang, C. C. Upregulation of presynaptic proteins and protein kinases associated with enhanced glutamate release from axonal terminals (synaptosomes) of the medial prefrontal cortex in rats with neuropathic pain. Pain 155, 377–387, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.10.026 (2014).

Kucyi, A. et al. Enhanced medial prefrontal-default mode network functional connectivity in chronic pain and its association with pain rumination. J Neurosci 34, 3969–3975, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5055-13.2014 (2014).

Moriarty, O., McGuire, B. E. & Finn, D. P. The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog Neurobiol 93, 385–404, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.002 (2011).

McCracken, L. M., Klock, P. A., Mingay, D. J., Asbury, J. K. & Sinclair, D. M. Assessment of satisfaction with treatment for chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 14, 292–299 (1997).

Veldhuijzen, D. S., Kenemans, J. L., de Bruin, C. M., Olivier, B. & Volkerts, E. R. Pain and attention: attentional disruption or distraction? J Pain 7, 11–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2005.06.003 (2006).

Elomaa, M. M., de, C. W. A. C. & Kalso, E. A. Attention management as a treatment for chronic pain. Eur J Pain 13, 1062–1067, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.12.002 (2009).

Bloem, B. et al. Topographic mapping between basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and the medial prefrontal cortex in mice. J Neurosci 34, 16234–16246, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3011-14.2014 (2014).

Fuchs, P. N., Peng, Y. B., Boyette-Davis, J. A. & Uhelski, M. L. The anterior cingulate cortex and pain processing. Front Integr Neurosci 8, 35, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2014.00035 (2014).

Cifre, I. et al. Disrupted functional connectivity of the pain network in fibromyalgia. Psychosom Med 74, 55–62, https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182408f04 (2012).

Yuan, W. et al. A pharmaco-fMRI study on pain networks induced by electrical stimulation after sumatriptan injection. Exp Brain Res 226, 15–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-013-3405-8 (2013).

Kelly, C. J., Huang, M., Meltzer, H. & Martina, M. Reduced Glutamatergic Currents and Dendritic Branching of Layer 5 Pyramidal Cells Contribute to Medial Prefrontal Cortex Deactivation in a Rat Model of Neuropathic Pain. Front Cell Neurosci 10, 133, https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2016.00133 (2016).

Ong, W. Y., Stohler, C. S. & Herr, D. R. Role of the Prefrontal Cortex in Pain Processing. Mol Neurobiol, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1130-9 (2018).

Cordeiro Matos, S., Zhang, Z. & Seguela, P. Peripheral Neuropathy Induces HCN Channel Dysfunction in Pyramidal Neurons of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex. J Neurosci 35, 13244–13256, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0799-15.2015 (2015).

Decosterd, I. & Woolf, C. J. Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 87, 149–158, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00276-1 (2000).

Kummer, K. K., El Rawas, R., Kress, M., Saria, A. & Zernig, G. Social interaction and cocaine conditioning in mice increase spontaneous spike frequency in the nucleus accumbens or septal nuclei as revealed by multielectrode array recordings. Pharmacology 95, 42–49, https://doi.org/10.1159/000370314 (2015).

Ting, J. T., Daigle, T. L., Chen, Q. & Feng, G. Acute brain slice methods for adult and aging animals: application of targeted patch clamp analysis and optogenetics. Methods Mol Biol 1183, 221–242, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1096-0_14 (2014).

Bischofberger, J., Engel, D., Li, L., Geiger, J. R. & Jonas, P. Patch-clamp recording from mossy fiber terminals in hippocampal slices. Nat Protoc 1, 2075–2081, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2006.312 (2006).

Franklin, K. B. J. & Paxinos, G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 3rd Editio edn, (Academic Press, 2007).

van Aerde, K. I. & Feldmeyer, D. Morphological and physiological characterization of pyramidal neuron subtypes in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 25, 788–805, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bht278 (2015).

Quarta, S. et al. Impaired mechanical, heat, and cold nociception in a murine model of genetic TACE/ADAM17 knockdown. FASEB J, fj201801901R, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201801901R (2018).

Golowasch, J. et al. Membrane capacitance measurements revisited: dependence of capacitance value on measurement method in nonisopotential neurons. J Neurophysiol 102, 2161–2175, https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00160.2009 (2009).

Sholl, D. A. Dendritic organization in the neurons of the visual and motor cortices of the cat. Journal of anatomy 87, 387–406 (1953).

Cheriyan, J. & Sheets, P. L. Altered Excitability and Local Connectivity of mPFC-PAG Neurons in a Mouse Model of Neuropathic Pain. J Neurosci 38, 4829–4839, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2731-17.2018 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Role of Prelimbic GABAergic Circuits in Sensory and Emotional Aspects of Neuropathic Pain. Cell Rep 12, 752–759, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.001 (2015).

Martinez, E. et al. Corticostriatal Regulation of Acute Pain. Front Cell Neurosci 11, 146, https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2017.00146 (2017).

Hardy, S. G. P. & Haigler, H. J. Prefrontal Influences Upon the Midbrain - a Possible Route for Pain Modulation. Brain Research 339, 285–293, https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(85)90094-0 (1985).

Cooper, S. J. Anaesthetisation of prefrontal cortex and response to noxious stimulation. Nature 254, 439–440 (1975).

Hardy, S. G. Analgesia elicited by prefrontal stimulation. Brain Res 339, 281–284 (1985).

Wei, F. et al. Genetic enhancement of inflammatory pain by forebrain NR2B overexpression. Nat Neurosci 4, 164–169, https://doi.org/10.1038/83993 (2001).

Dale, J. et al. Scaling Up Cortical Control Inhibits Pain. Cell Rep 23, 1301–1313, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.139 (2018).

Cheriyan, J., Kaushik, M. K., Ferreira, A. N. & Sheets, P. L. Specific Targeting of the Basolateral Amygdala to Projectionally Defined Pyramidal Neurons in Prelimbic and Infralimbic Cortex. eNeuro 3, https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0002-16.2016 (2016).

Vidal-Gonzalez, I., Vidal-Gonzalez, B., Rauch, S. L. & Quirk, G. J. Microstimulation reveals opposing influences of prelimbic and infralimbic cortex on the expression of conditioned fear. Learn Mem 13, 728–733, https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.306106 (2006).

Laurent, V. & Westbrook, R. F. Inactivation of the infralimbic but not the prelimbic cortex impairs consolidation and retrieval of fear extinction. Learn Mem 16, 520–529, https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.1474609 (2009).

Sierra-Mercado, D., Padilla-Coreano, N. & Quirk, G. J. Dissociable roles of prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, ventral hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala in the expression and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 529–538, https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.184 (2011).

Jiang, Z. C. et al. Inactivation of the prelimbic rather than infralimbic cortex impairs acquisition and expression of formalin-induced conditioned place avoidance. Neurosci Lett 569, 89–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2014.03.074 (2014).

Wang, G. Q. et al. Deactivation of excitatory neurons in the prelimbic cortex via Cdk5 promotes pain sensation and anxiety. Nat Commun 6, 7660, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8660 (2015).

Shiers, S. et al. Neuropathic Pain Creates an Enduring Prefrontal Cortex Dysfunction Corrected by the Type II Diabetic Drug Metformin But Not by Gabapentin. J Neurosci 38, 7337–7350, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0713-18.2018 (2018).

Kelly, C. J. & Martina, M. Circuit-selective properties of glutamatergic inputs to the rat prelimbic cortex and their alterations in neuropathic pain. Brain Struct Funct 223, 2627–2639, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-018-1648-7 (2018).

Alvarado, S. et al. Peripheral nerve injury is accompanied by chronic transcriptome-wide changes in the mouse prefrontal cortex. Mol Pain 9, 21, https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-9-21 (2013).

Kepecs, A. & Fishell, G. Interneuron cell types are fit to function. Nature 505, 318–326, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12983 (2014).

Ciceri, G. et al. Lineage-specific laminar organization of cortical GABAergic interneurons. Nat Neurosci 16, 1199–1210, https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3485 (2013).

Cichon, J., Blanck, T. J. J., Gan, W. B. & Yang, G. Activation of cortical somatostatin interneurons prevents the development of neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci 20, 1122–1132, https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4595 (2017).

Chen, T. et al. Top-down descending facilitation of spinal sensory excitatory transmission from the anterior cingulate cortex. Nat Commun 9, 1886, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04309-2 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Touch and tactile neuropathic pain sensitivity are set by corticospinal projections. Nature 561, 547–550, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0515-2 (2018).

Sorge, R. E. & Totsch, S. K. Sex Differences in Pain. J Neurosci Res 95, 1271–1281, https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.23841 (2017).

Fillingim, R. B., King, C. D., Ribeiro-Dasilva, M. C., Rahim-Williams, B. & Riley, J. L. 3rd Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain 10, 447–485, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001 (2009).

Straube, T., Schmidt, S., Weiss, T., Mentzel, H. J. & Miltner, W. H. Sex differences in brain activation to anticipated and experienced pain in the medial prefrontal cortex. Hum Brain Mapp 30, 689–698, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20536 (2009).

Nishinaka, T., Nakamoto, K. & Tokuyama, S. Early life stress induces sex-dependent increases in phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase in brains of mice with neuropathic pain. Eur J Pain 20, 1346–1356, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.860 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grants (DK-SPIN W1206-06 to M.K., DK-SPIN W1206-10 to F.F. and P30809 to K.K.) and the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) grant (D-150700-013-017 to M.K.). We are grateful for excellent technical support by Theresa Martha.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M., K.K. and M.K. designed the study. M.M., A.S. and G.M. performed the experiments. M.M., K.K., A.S., G.M., F.F. and M.K. performed the data analysis and interpreted the data. M.M., K.K., F.F. and M.K. wrote the manuscript. A.S., G.M. and P.S. critically reviewed the contents of the paper and suggested substantial improvements. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitrić, M., Seewald, A., Moschetti, G. et al. Layer- and subregion-specific electrophysiological and morphological changes of the medial prefrontal cortex in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. Sci Rep 9, 9479 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45677-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45677-z

This article is cited by

-

Loss of mGlu5 receptors in somatostatin-expressing neurons alters negative emotional states

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

Chronic Pain–Related Cognitive Deficits: Preclinical Insights into Molecular, Cellular, and Circuit Mechanisms

Molecular Neurobiology (2024)

-

Circuit- and laminar-specific regulation of medial prefrontal neurons by chronic stress

Cell & Bioscience (2023)

-

Programmable RNA sensing for cell monitoring and manipulation

Nature (2022)

-

Prenatal dexamethasone exposure alters effort decision making and triggers nucleus accumbens and anterior cingulate cortex functional changes in male rats

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.