Abstract

Species’ responses to climate change will reflect variability in the effects of physiological selection that future conditions impose. Here, we considered the effects of ocean acidification (increases in pCO2; 606, 925, 1250 µatm) and freshening (reductions in salinity; 33, 23, 13 PSU) on sperm motility in oysters (Crassostrea gigas) from two populations (one recently invaded, one established for 60+ years). Freshening reduced sperm motility in the established population, but this was offset by a positive effect of acidification. Freshening also reduced sperm motility in the recently invaded population, but acidification had no effect. Response direction, strength, and variance differed among individuals within each population. For the established population, freshening increased variance in sperm motility, and exposure to both acidification and freshening modified the performance rank of males (i.e. rank motility of sperm). In contrast, for the recently invaded population, freshening caused a smaller change in variance, and male performance rank was broadly consistent across treatments. That inter-population differences in response may be related to environmental history (recently invaded, or established), indicates this could influence scope for selection and adaptation. These results highlight the need to consider variation within and among population responses to forecast effects of multiple environmental change drivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Species’ responses to climate change vary among levels of organisation. For example, differences have been found among Phyla1, among populations of the same species2,3,4, and among individuals of the same populations5,6,7. Where variation in responses is large and heritable there is greater scope for selection8,9 and, thereby, the potential for fitness to be influenced10,11. Consequently, understanding response variability among individuals is fundamental to identifying the potential for adaptation, and improving our ability to predict impacts of future change3.

Strong selective pressures on reproduction can carry over into subsequent life stages. For example, sperm selection plays a key role in shaping the subsequent generation in many broadcast-spawning marine organisms12,13. Moreover, gametes of broadcast-spawning organisms are often particularly sensitive to selection as they are released into the environment and typically possess limited buffering capacities8,14,15. Where environmental conditions modify gamete motility, selection may act upon individuals to result in the modification, or loss, of certain populations16.

Ongoing ocean acidification will likely generate significant novel selection pressures. While many studies have indicated that ocean acidification could lead to reduced sperm motility8,17,18,19, others have found it can remain unchanged20, or even increase21. Yet ocean acidification does not operate in isolation, and many studies show that multiple simultaneous drivers can have very different effects to those of drivers operating alone22. Climate projections indicate than in many regions freshening – the decline in seawater salinity – will arise from altered patterns of precipitation and ice sheet melt23,24,25. When experienced in isolation, freshening is reported to lower sperm motility in a range of species (e.g. Atlantic cod Gadus morhua26, polychaete Galeolaria caespitosa, and Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas27). However, the combined effects of freshening and ocean acidification on sperm motility remain unassessed.

We, therefore, measured the effects of ocean acidification and freshening on sperm motility at both the population and individual levels. To study these effects we used the model oyster species C. gigas. C. gigas is an important aquaculture and invasive species28, whose persistence into the future may be modified as its reproduction can be influenced by both ocean acidification29 and salinity30. Here, we tested: (1) the effects of ocean acidification and freshening on sperm motility; (2) if (and how) these effects varied between populations and among individuals; and (3) the impacts of acidification and freshening on male performance rank. We investigated these responses in C. gigas individuals sampled from two populations: one that invaded the low-salinity west coast of Sweden recently (within ≤10 years of this study; termed “invasive”), and one that has been established for 60+ years in the stable full-salinity waters of Guernsey, British Channel Islands (termed “established”). This work contributes to developing a broader understanding of the extent to which populations, and male performance broadly, will be modified in the future.

Results

Across populations, sperm motility declined with freshening (Fig. 1). Responses to acidification, however, differed; sperm motility increased with acidification in males from the established population, whereas sperm motility did not change substantively with acidification for those from the recently invaded population (open vs closed circles respectively, Fig. 1). Consequently, for established population males, the positive effects of acidification offset the negative effects of freshening such that their combination resulted in sperm motility that was equivalent to that in control conditions (i.e. LnRR ≈ 0; Fig. 1). Similar antagonistic effects of freshening and acidification were not seen in males from the recently invaded population, which therefore showed freshening-induced reductions in sperm motility under future climate scenarios. These findings were reflected in the formal PERMANOVA results (Table 1), which showed that the two populations responded differently to pCO2 (Population × pCO2, p = < 0.01), and that responses to pCO2 and freshening varied significantly among individuals (Salinity × pCO2 × Individual[Population], p = < 0.01).

Mean effects (mean loge response ratio, LnRR, ±95% CI) of ocean acidification (pCO2, µatm) and freshening (salinity, PSU) on sperm motility (measured in terms of Sperm Accumulated At Surface, SAAS) in oysters from two populations (invasive, Sweden, closed circles and established, Guernsey, open circles; n = 14 per population). LnRR’s calculated using 606 µatm CO2 × 33 PSU as reference. Note difference in scale on y-axis from Fig. 2.

Sperm from different males responded differently to the treatments in terms of their motility; some males showed improvements in sperm motility under acidification and freshening, whereas others were negatively affected (Fig. 2). Freshening caused a clear increase in response variance among males, especially in the established population (Fig. 2). In contrast, acidification had no effect on response variance.

Individual effects (loge response ratio, LnRR) of ocean acidification (pCO2, µatm) and freshening (salinity, PSU) on sperm motility (measured in terms of Sperm Accumulated At Surface, SAAS) in oysters from two populations (invasive, closed circles and established, open circles). LnRR’s calculated using 606 µatm CO2 × 33 PSU as reference. Note difference in scale on y-axis from Fig. 1.

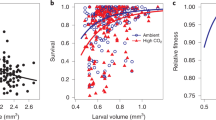

Differential sensitivity of males to acidification and freshening was reflected in relative male performance, which was calculated for each treatment as the percentage of total sperm contacts (SAAS) for that population that were obtained by any given individual (Fig. 3). In the recently invaded population, males that performed best (i.e. had a high performance rank) in control conditions tended to retain performance rank under acidification and freshening (e.g. small changes in performance rank in solid-red, dotted-blue, and dashed-yellow lines in Fig. 3, upper panels). In the established population, however, the highest ranked male under control conditions was one of the poorest-performing males when exposed to acidification and freshening, and vice versa (change from 1st to 13th in solid-red line, and from 7th to 1st in dashed-yellow line, Fig. 3, lower panels). This population-wise difference in effect of acidification and freshening on male performance was seen clearly in correlations of performance rank among the treatments (Table 2). Rank order of performance in males from the recently invaded population under control conditions was significantly correlated with that under all combinations of acidification and freshening (p ≤ 0.05, Table 2), whereas performance rank in males from the established population were only significantly correlated between control conditions and acidification at 33 PSU. No negative rank-order correlations were observed.

Change in male performance rank with ocean acidification (pCO2, µatm) and freshening (salinity, PSU). Data are sperm contacts for each male as a percentage of total number of sperm contacts (sum of all contacts for all males) in each treatment. Lines represent individual males. For each population: the highest performing male in the ambient (control) treatment (606 µatm CO2, 33‰) is indicated by a solid/red line; the lowest performing male in the control treatment is indicated by a dotted/blue line; the highest performing male in the most extreme treatment (1250 µatm CO2, 13‰) is indicated by a dashed/orange line.

Discussion

Our finding that different populations, and individuals, of oysters showed distinctly different responses to ocean acidification and freshening could have pervasive implications for this species under marine climate change. We measured sperm motility using a metric (SAAS27) that integrates sperm swimming speed and percent motility, two key determinants of fertilisation success in free-spawning organisms31,32. Consequently, the large changes in motility we observed under acidification and freshening imply that these drivers could cause correspondingly large shifts in fertilisation success for individuals33. If sperm responses to acidification and freshening are heritable, these findings indicate there is substantial, and population-dependent, potential for selection and adaptation of this species under future climate change.

At the population level, clear patterns of response in oyster sperm motility emerged. Average sperm motility for the individuals we sampled from an established population increased with acidification, but decreased with freshening, such that these two drivers cancelled each other out at low salinity and high pCO2; a combination that is likely to manifest regionally in the future. In contrast, sperm motility of oysters sampled from an invasive population was unaffected by acidification (a result also obtained previously20), but decreased with freshening irrespective of pCO2. Such population-level differences in the effects of acidification have also been reported in another oyster (i.e. Sydney rock oyster, Saccostrea glomerata3). It is possible the different responses we observed were driven by parental environmental history34 and/or local adaptation35, although in that context it is surprising that oysters from the invasive population, which has recently undergone strong selection for tolerance to low salinities28, generally responded more negatively to freshening than those oysters from the established population that has lived many decades in ≈34 PSU. Equally, it is possible that some form of bottleneck or founder event has resulted in reduced genetic diversity of the invasive population (relative to the established population)36,37. Irrespective of the mechanism, such population-specific findings highlight the difficulties – and dangers – of forecasting species responses to climate drivers based on investigations of only one population.

Each of the populations considered showed substantial inter-individual variation in sperm motility responses. While some oysters responded negatively to treatments, others showed no response, with some responding positively. Such patterns of strong inter-individual variability in responses can reflect differences among parental genotypes and environments that then influence gametes exposed to different environmental conditions38,39. Alternatively, differences among individuals could result from non-genetic paternal effects such as differential gamete maturity. Variability between individuals has been reported previously in the context of organism responses to ocean acidification7,8,20,33,40. We are, however, unaware of any other study that has investigated the effects of multiple climate change-related drivers on individual sperm performance (but for the combined effects of ocean acidification and a toxicant – i.e. copper – see41). The growing body of literature showing that inter-individual variability in responses may be common42, argues for shifting focus away from understanding “mean” responses and toward investigating changes in variance and (hence) the potential for differential individual success in a future ocean.

Importantly, we found that variability of individual responses itself varied among populations and treatments. Freshening led to a clear increase in inter-individual variance in sperm motility (SAAS), particularly in the established population. In contrast, acidification had no effect on response variance, which – within each salinity – remained more or less constant in both populations. As noted earlier, shifts in variance of these populations may have been influenced by the environment of the parental organism. That is, the narrower response variance seen in oysters from the invasive population (Fig. 2) could reflect the strong salinity-driven selection this invasive population has recently experienced28, potentially reducing phenotypic variance. Alternately, this could be due to bottleneck and/or founder events that caused reductions in genetic diversity of these populations36,37. Nonetheless, recent work has shown local selection in this species can be pervasive35. Despite differences in magnitude of responses, the general pattern of increased variance under freshening indicates that differences among males will be amplified, a pattern which could have implications for male competitiveness during broadcast spawning.

The relative performance of sperm from different males shifted under the combined effects of acidification and freshening. For the established population, males that performed well under control (ambient) conditions performed poorly when exposed to acidification and freshening (Fig. 3, Table 2). This is the first such result for multiple climate drivers and extends a recent observation that acidification can change the male fitness landscape in broadcast spawners, and that this response can be modified by a co-factor (specifically a heavy metal5). In the invasive population, however, the relative performance of male oysters from the invasive population showed no substantive shift under freshening and acidification: males that performed well under control conditions continued to perform well under freshening and acidification (Fig. 3, Table 2). Given that sperm motility is a key determinant of fertilisation success31,32 – and hence adaptive capacity – continuing to explore how this feature can be modified by climate drivers and by the environmental history of a given population should be a focus of future research.

In conclusion, despite the burgeoning number of studies reporting effects of ocean acidification on the early life history of marine organisms, few have considered the importance of response variability, particularly for multiple climate drivers. Here, we show that the influence of ocean acidification on sperm motility and performance rank of individual male oysters can be strongly modified when combined with freshening, an effect that differs between populations and among individuals. This finding shows that quantifying inter- and intra-population response variability will be essential if we are to reliably project species’ responses to future climate drivers.

Methods

Experimental design

We investigated responses of sperm from multiple male oysters from two populations (n = 14 individuals from each population), to three levels of pCO2 and three levels of salinity in a fully-factorial design.

Experimental organisms

Pacific oysters were collected in the summer of 2015 from an “established” population, which has been exposed to oceanic seawater for over 60 years at Guernsey Sea Farms, British Channel Islands. This population is open to some immigration, and is genetically representative of farmed populations from which feral populations have established and spread. These oysters were conditioned to reproductive maturity by Guernsey Sea Farms Ltd, Vale, Channel Islands, and shipped to the Tjärnö Marine Laboratory, Sweden, immediately prior to experimentation. Oysters were also collected haphazardly from a recent “invasive” population (established ≤10 years prior to this study28) in western Sweden. This environment is characterised by highly variable salinity and pH (13–30 PSU, 7.7–8.1 pH)43. Following collection, oysters from the invasive population were conditioned to reproductive maturity by Ostrea Sverige AB, South Koster, Sweden, with the same methods used by Guernsey Sea Farms Ltd. Conditioned oysters were held in temperature-controlled flowing seawater at the Tjärnö Marine Laboratory at 33 PSU and 17 °C (just below the temperature that elicits spawning) until experiments were run.

Experimental treatments

pCO2 treatment levels were selected to reflect ambient inflowing seawater pCO2 at the Tjärnö Marine Laboratory (606 µatm), late-century atmospheric pCO2 (925 µatm), and end-of-century atmospheric pCO2 (1250 µatm) under prevalent global climate change scenarios44. Treatment levels were achieved by bubbling CO2-air mixtures into the treatment water until a given target pHNBS was obtained. pHNBS set-points equivalent to treatment pCO2 levels were determined by calibrating pHNBS against inflowing seawater equilibrated for 24 h with custom mixed gases of the relevant CO2 concentration (AGA, Sweden AB). The response slope of the pH meter was calibrated daily using NBS buffers. Total alkalinity was estimated from salinity using a long-term salinity:alkalinity relationship for this location (r = 0.94)43. This method has been shown to generate very low uncertainties in estimates of carbonate system parameters (uncertainties ≤±0.006 pHNBS and ±0.08 ΩAr) (for more details see45). pCO2 and saturation states for calcite (ΩCa) and aragonite (ΩAr) were calculated using CO2calc46, with constants from Mehrbach et al.47 adjusted by Dickson and Millero48 (Table 3).

Salinity treatment levels were chosen to reflect the full-strength seawater typical of Guernsey (33 PSU), local sea surface salinity at Tjärnö, western Sweden (23 PSU), and sea-surface salinity in south-western Sweden (13 PSU), toward which the invasive oysters are spreading28. Salinity was manipulated by diluting filtered sea water with filtered fresh water. Treatment levels were verified using a conductivity meter (WTW, Cond 3210, Germany) calibrated against laboratory salinity standards (Table 3).

Response variable: sperm motility (SAAS)

Sperm motility for each replicate male (n = 14 per population), was quantified by measuring Sperm Accumulated Against Surface (SAAS)27 under all combinations of pCO2 and salinity. For each male oyster, concentrated sperm were extracted directly from the testis using a Pasteur pipette inserted through a hole drilled in the shell above the gonad. Previous work has shown that any non-motile sperm released by this technique will have had minimal impact on the results27. Namely, SAAS is almost exclusively caused by actively swimming sperm, and the sinking rate of dead/inactive sperm is so slow that it does not bias results obtained using the technique. Concentrated sperm were stored in an Eppendorf tube on ice. Sperm concentration in each suspension was verified by hemocytometer counts of an aliquot of sperm that had been immobilised and stained with Lugol’s solution. For each male, independent sub-samples of sperm from the stock suspension were diluted into each of three replicate wells of a multi-well plate containing treatment seawater (three replicates per treatment combination and male). Volumes of sperm transferred were adjusted to ensure a final concentration of 2 × 106 sperm ml−1 in the treatments. Sperm were exposed to the treatment seawater for 10 min, after which 1.5 ml of the suspension was pipetted to a new multi-well plate from which the pattern of accumulation of sperm on the bottom surface of the well over time was quantified. Sperm counts were determined using a phase-contrast inverted microscope (Leica, DMIL, Germany) equipped with a digital camera (PixeLINK, PL-D725CU, Canada). To quantify accumulation, still images of different (central) areas of the lower surface of the wells were taken 10 min after the addition of the sperm suspension to the well (n = 3 images per well). Digital images were post-processed and the number of sperm that had accumulated at the lower surface of the well (SAAS) counted manually.

Statistical analysis

The response of sperm motility (SAAS) to pCO2 and salinity was determined by calculating logarithmic response ratios, LnRR = loge ([response in treatment]/[response in control]), for each treatment combination and male, using the 606 µatm CO2 × 33 PSU treatment as the control. Unlike raw ratio data, loge response ratios are approximately normally distributed49, and therefore we also calculated mean LnRR ± 95% CI. We determined the statistical significance of sperm responses to the treatments using a three-way permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using the PRIMER package50 with population, pCO2, and salinity as fixed factors, and individuals as a random factor (n = 14 per population, 3 replicates per male) nested within population. To reduce heterogeneity of variances, data were square root transformed before analysis.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kroeker, K. J. et al. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Global Change Biology 19, 1884–1896 (2013).

Waldbusser, G., Bergschneider, H. & Green, M. Size-dependent pH effect on calcification in post-larval hard clam Mercenaria spp. Marine Ecology Progress Series 417, 171–182 (2010).

Parker, L. M., Ross, P. M. & O’Connor, W. A. Populations of the Sydney rock oyster, Saccostrea glomerata, vary in response to ocean acidification. Marine Biology 158, 689–697 (2011).

Walther, K., Sartoris, F. J. & Pörtner, H. O. Impacts of temperature and acidification on larval calcium incorporation of the spider crab Hyas araneus from different latitudes (54° vs. 79°N). Marine Biology 158, 2043–2053 (2011).

Campbell, A. L., Levitan, D. R., Hosken, D. J. & Lewis, C. Ocean acidification changes the male fitness landscape. Scientific Reports 6, 31250 (2016).

Pistevos, J. C. A., Calosi, P., Widdicombe, S. & Bishop, J. D. D. Will variation among genetic individuals influence species responses to global climate change? Oikos 120, 675–689 (2011).

Schlegel, P., Havenhand, J. N., Obadia, N. & Williamson, J. E. Sperm swimming in the polychaete Galeolaria caespitosa shows substantial inter-individual variability in response to future ocean acidification. Marine Pollution Bulletin 78, 213–217 (2014).

Schlegel, P., Havenhand, J. N., Gillings, M. R. & Williamson, J. E. Individual variability in reproductive success determines winners and losers under ocean acidification: a case study with sea urchins. PLOS ONE 7, e53118 (2012).

Foo, S. A., Dworjanyn, S. A., Poore, A. G. B. & Byrne, M. Adaptive capacity of the habitat modifying sea urchin Centrostephanus rodgersii to ocean warming and ocean acidification: performance of early embryos. PLOS ONE 7, e42497 (2012).

Reed, D. H. & Frankham, R. Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity. Conservation Biology 17, 230–237 (2003).

Frankham, R. Conservation biology: ecosystem recovery enhanced by genotypic diversity. Heredity 95, 183–183 (2005).

Levitan, D. R. Gamete traits influence the variance in reproductive success, the intensity of sexual selection, and the outcome of sexual conflict among congeneric sea urchins. Evolution 62, 1305–1316 (2008).

Levitan, D. R. Effects of gamete traits on fertilization in the sea and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Nature 382, 153–155 (1996).

Graham, H. et al. Sperm motility and fertilisation success in an acidified and hypoxic environment. ICES Journal of Marine Science 73, 783–790 (2016).

Gazeau, F. et al. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine shelled molluscs. Marine Biology 160, 2207–2245 (2013).

Schlegel, P., Binet, M. T., Havenhand, J. N., Doyle, C. J. & Williamson, J. E. Ocean acidification impacts on sperm mitochondrial membrane potential bring sperm swimming behaviour near its tipping point. The Journal of Experimental Biology 218, 1084–90 (2015).

Havenhand, J. N., Buttler, F.-R., Thorndyke, M. C. & Williamson, J. E. Near-future levels of ocean acidification reduce fertilization success in a sea urchin. Current Biology 18, R651–R652 (2008).

Morita, M. et al. Ocean acidification reduces sperm flagellar motility in broadcast spawning reef invertebrates. Zygote 18, 103–107 (2010).

Vihtakari, M. et al. Effects of ocean acidification and warming on sperm activity and early life stages of the Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis). Water 5, 1890–1915 (2013).

Havenhand, J. N. & Schlegel, P. Near-future levels of ocean acidification do not affect sperm motility and fertilization kinetics in the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Biogeosciences 6, 3009–3015 (2009).

Caldwell, G. S. et al. Ocean acidification takes sperm back in time. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development 55, 217–221 (2011).

Boyd, P. W. et al. Experimental strategies to assess the biological ramifications of multiple drivers of global ocean change - a review. Global Change Biology 24, 2239–2261 (2018).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. & Bruno, J. F. The impact of climate change on the world’s marine ecosystems. Science 328, 1523–8 (2010).

Doney, S. C. et al. Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems. Annual Review of Marine Science 4, 11–37 (2012).

Shi, P., Sun, S., Gong, D. & Zhou, T. World Regionalization of Climate Change (1961–2010). International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 7, 216–226 (2016).

Litvak, M. K. & Trippel, E. A. Sperm motility patterns of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in relation to salinity: effects of ovarian fluid and egg presence. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 55, 1871–1877 (1998).

Falkenberg, L. J., Havenhand, J. N. & Styan, C. A. Sperm Accumulated Against Surface: a novel alternative bioassay for environmental monitoring. Marine Environmental Research 114, 51–57 (2016).

Wrange, A.-L. et al. Massive settlements of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, in Scandinavia. Biological Invasions 12, 1145–1152 (2010).

Parker, L. M., Ross, P. M. & O’Connor, W. A. Comparing the effect of elevated pCO2 and temperature on the fertilization and early development of two species of oysters. Marine Biology 157, 2435–2452 (2010).

Muranaka, M. S. & Lannan, J. E. Broodstock management of Crassostrea gigas: environmental influences on broodstock conditioning. Aquaculture 39, 217–228 (1984).

Styan, C. A. Polyspermy, egg size, and the fertilization kinetics of free-spawning marine invertebrates. The American Naturalist 152, 290–297 (1998).

Vogel, H., Czihak, G., Chang, P. & Wolf, W. Fertilization kinetics of sea urchin eggs. Mathematical Biosciences 58, 189–216 (1982).

Vihtakari, M., Havenhand, J., Renaud, P. E. & Hendriks, I. E. Variable individual- and population- level responses to ocean acidification. Frontiers in Marine Science 3, 51 (2016).

Hofmann, G. E. et al. Exploring local adaptation and the ocean acidification seascape - studies in the California Current Large Marine Ecosystem. Biogeosciences 11, 1053–1064 (2014).

Li, L. et al. Divergence and plasticity shape adaptive potential of the Pacific oyster. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2, 1751–1760 (2018).

Rohfritsch, A. et al. Population genomics shed light on the demographic and adaptive histories of European invasion in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Evolutionary Applications 6, n/a–n/a (2013).

Anglès d′Auriac, M. B. et al. Rapid expansion of the invasive oyster Crassostrea gigas at its northern distribution limit in Europe: Naturally dispersed or introduced? PLOS ONE 12, e0177481 (2017).

Crean, A. J., Dwyer, J. M. & Marshall, D. J. Adaptive paternal effects? Experimental evidence that the paternal environment affects offspring performance. Ecology 94, 2575–2582 (2013).

Jensen, N., Allen, R. M. & Marshall, D. J. Adaptive maternal and paternal effects: gamete plasticity in response to parental stress. Functional Ecology 28, 724–733 (2014).

Frommel, A. Y., Stiebens, V., Clemmesen, C. & Havenhand, J. Effect of ocean acidification on marine fish sperm (Baltic cod: Gadus morhua). Biogeosciences 7, 3915–3919 (2010).

Campbell, A. L., Mangan, S., Ellis, R. P. & Lewis, C. Ocean acidification increases copper toxicity to the early life history stages of the polychaete Arenicola marina in artificial seawater. Environmental Science & Technology 48, 9745–9753 (2014).

Calosi, P. et al. Multiple physiological responses to multiple environmental challenges: an individual approach. Integrative and Comparative Biology 53, 660–670 (2013).

SMHI. Swedish Oceanographic Data Centre. Available at, http://www.smhi.se/oceanografi/oce_info_data/SODC/download_en.htm (2011).

Collins, M. et al. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2013).

Eriander, L., Wrange, A.-L. & Havenhand, J. N. Simulated diurnal pH fluctuations radically increase variance in—but not the mean of—growth in the barnacle Balanus improvisus. ICES Journal of Marine Science 73, 596–603 (2016).

Robbins, L. L., Hansen, M. E., Kleypas, J. A. & Meylan, S. C. CO2calc: a user-friendly seawater carbon calculator for Windows, Mac OS X, and iOS (iPhone). Open-File Report, https://doi.org/10.3133/OFR20101280 (2010).

Mehrbach, C., Culberson, C. H., Hawley, J. E. & Pytkowicx, R. M. Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmpospheric pressure. Limnology and Oceanography 18, 897–907 (1973).

Dickson, A. G. & Millero, F. J. A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 34, 1733–1743 (1987).

Nakagawa, S. & Cuthill, I. C. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biological Reviews 82, 591–605 (2007).

Anderson, M. J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecology 26, 32–46 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We offer our heartfelt thanks to Alexandra Kinnby and Ostrea Sverige AB. Funds provided to UCL by Santos supported LJF, and the Linnaeus Centre for Marine Evolutionary Biology at the University of Gothenburg (http://www.cemeb.science.gu.se) and Project grant #2014-1193 from Formas supported JNH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.J.F., C.A.S. and J.N.H. developed the project; L.J.F. conducted the experiments; L.J.F. and J.N.H. analysed and plotted the data; L.J.F., C.A.S. and J.N.H. prepared and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Falkenberg, L.J., Styan, C.A. & Havenhand, J.N. Sperm motility of oysters from distinct populations differs in response to ocean acidification and freshening. Sci Rep 9, 7970 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44321-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44321-0

This article is cited by

-

Effects of irradiance, temperature, nutrients, and pCO2 on the growth and biochemical composition of cultivated Ulva fenestrata

Journal of Applied Phycology (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.