Abstract

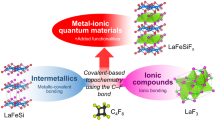

We report a simple one-pot synthesis of uniform transition metal difluoride MF2 (M = Fe, Mn, Co) nanorods based on transition metal trifluoroacetates (TMTFAs) as single-source precursors. The synthesis of metal fluorides is based on the thermolysis of TMTFAs at 250–320 °C in trioctylphosphine/trioctylphosphine oxide solvent mixtures. The FeF2 nanorods were converted into FeF3 nanorods by reaction with gaseous fluorine. The TMTFA precursors are also found to be suitable for the synthesis of colloidal transition metal phosphides. Specifically, we report that the thermolysis of a cobalt trifluoroacetate complex in trioctylphosphine as both the solvent and the phosphorus source can yield 20 nm long cobalt phosphide nanorods or, 3 nm large cobalt phosphide nanoparticles. We also assess electrochemical lithiation/de-lithiation of the obtained FeF2 and FeF3 nanomaterials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Synthesis of nanoscale inorganic materials remains an active research area in inorganic chemistry, owing to the unique and improved material properties that emerge with respect to their bulk counterparts1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Downsizing is particularly important for conversion-type cathode materials for Li-ion batteries such as transition metal fluorides. These compounds offer one of the highest capacities among conventional cathode materials (e.g., 571 mAh g−1 for FeF2, 237 mAh g−1 for FeF3 vs. 148 mAh g−1 for LiCoO2)8,9, but suffer from reduced rate capabilities and cycling stabilities, which are associated with low electronic conductivity and considerable structural reconstruction of the electrodes during cycling10,11,12,13,14,15,16. In this context, reducing the primary grain size of materials has become the main strategy for reducing polarization and improving the overall kinetics of Li+ insertion. Nanosized materials have a considerably shorter in-solid diffusion path with less mechanical stress during phase conversion.

The synthesis of uniform transition metal difluoride nanocrystals (NCs) and nanoparticles (NPs) is generally complicated by the highly reactive and hazardous nature of commonly used fluorine sources, e.g., F217, HF18, and NH4F19,20. Several liquid-phase chemical approaches, including co-precipitation19,20,21,22,23, hydrothermal24,25,26,27, and solvothermal28,29 syntheses, have been used to synthesize transition metal fluorides. However, these methods yield NCs of irregular shape and broad size distributions. In 2005, an alternative approach was reported by Yan et al.30 for the synthesis of LaF3 nanoparticles (NPs) based on thermolysis of a single-source lanthanum trifluoroacetate precursor in high-boiling point organic solvents. The proposed surfactant-assisted synthetic pathway enabled control over nucleation and growth of LaF3 NPs by adjusting the capping ligands and the reaction temperature. In subsequent studies, a variety of different colloidal NPs, including NaYF431 and GdF332, were reported by Murray et al. based on single-source precursors. The reports of Yan et al.30,33,34, Murray et al.31,32 and others35,36,37,38,39,40 have guided this work, wherein we report on applications of transition metal (Fe, Mn, Co) trifluoroacetate complexes (TMTFAs) as precursors for the synthesis of uniform colloidal NPs of Fe, Mn, and Co difluorides. In these precursors, both transition metal and fluorine are integrated into one compound providing a high control over the size of transition metal (Fe, Mn, Co) fluoride NPs.

We achieved a colloidal synthesis of highly uniform Fe, Mn, and Co difluoride nanorods (NRs) through thermolysis of inexpensive TMTFAs in the solvents trioctylphosphine (TOP) and trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO). Control over the size and shape of these nanomaterials was achieved by adjusting the temperature and decomposition time and by the addition of oleic acid (OA) as a long-chain surface ligand. In addition, we show that CoF2 NRs can themselves serve as precursors for nanomaterial synthesis, yielding 20 nm long cobalt phosphide NRs or amorphous, 3 nm large cobalt phosphide NPs upon reaction with TOP. Furthermore, we used fluorine gas to synthesize FeF3 NRs by fluorination of FeF2 NRs. Finally, we present investigations of electrochemical lithiation/de-lithiation in the synthesized FeF2 and FeF3 NRs.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

FeCl3 anhydrous (Alfa Aeser, 98%, 12357), CoCl2 anhydrous (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥98.0% 60818), MnCl2 anhydrous (Alfa Aeser, 99%, 12315), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, Fischer, T/3255/PB05, 100 mL), trioctylphosphine (TOP, Strem, 15–6655, >97%), trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO, Strem, 15–6661, 99%), oleic acid (OA, Sigma-Aldrich, 364525), ethanol (Merck, 1.00983.1011), and toluene (Sigma-Aldrich, 34866).

Synthesis of Fe trifluoroacetate complex

[denoted as a “Fe3OTFA”]. “Fe3OTFA” was synthesized according to previous reports41. The chemical composition of “Fe3OTFA” precursor corresponds to the following formula: [Fe3(μ3-O)(CF3COO)(μ-CF3COO)6(H2O)2]·CF3COOH.

Synthesis of Co trifluoroacetate complex

[denoted as an “Co(TFA)2”]. CoCl2 (10 g, 0.077 moles) was mixed with trifluoroacetic acid (100 mL, 1.307 mol) in a 250 mL two-neck flask equipped with a double-mantled 30 cm long Dimroth cooler. The reaction mixture was refluxed at 95 °C for 3.5 days under nitrogen flow. The resulting blue solution was cooled to 50 °C and 100 mL of dried toluene was added to precipitate “Co(TFA)2”. The product was filtrated under a N2 atmosphere following by a washing step with dried toluene (30 mL) and drying under vacuum for 24 h. The product is highly hygroscopic. Its crystal structure is unknown (powder XRD pattern of the “Co(TFA)2” precursor is shown on Figure S1).

Synthesis of Mn trifluoroacetate complex

[denoted as an “Mn(TFA)2”]. “Mn(TFA)2” was synthesized according to previous reports41. The chemical composition of the “Mn(TFA)2” precursor corresponds to the following formula: Mn2(CF3COO)4(CF3COOH)4.

Synthesis of FeF2 NRs

“Fe3OTFA” (562 mg, 0.5 mmol), was mixed with TOP (10 mL, 22.4 mmol) and OA (0–0.952 mL, 0–3 mmol) in a 50 mL three-neck flask. Afterward, the reaction mixture was dried under vacuum at 110 °C for 1.5 h followed by heating to 320 °C at a heating rate of 6–18 °C min−1. Finally, the reaction was quenched to 200 °C with compressed air followed by cooling in an ice-water bath with concomitant injection of anhydrous toluene (20 mL) into the crude solution at approximately 120 °C. Different amounts of OA and different heating rates controlled the length of the FeF2 NRs (see SI for details, Table S1). The FeF2 NRs were washed two times with a toluene/ethanol mixture and separated by centrifugation. After the second washing step, the NRs were redispersed in toluene (2–4 mL) and stored under ambient conditions.

Synthesis of MnF2 NRs/NPs

Colorless “Mn(TFA)2” powder (509 mg, 0.5 mmol) was mixed with TOPO (8.8 g, 23 mmol) or TOP (10 mL, 22 mmol) in a 50 mL three-neck flask under a N2 flow to obtain short (15–20 nm) or long (25–35 nm) MnF2 NRs, respectively. Then, the reaction mixture was dried under vacuum at 110 °C for 1.5 h followed by slow heating (6 °C min−1) to 250 °C under a N2 flow (see SI for details, Table S2). Afterward, the reaction mixture was quenched following the washing procedure as described above for FeF2 NRs.

Synthesis of CoF2 NRs/NPs

“Co(TFA)2” (0.5 g) was mixed with TOPO (8.8 g, 23 mmol) and OA (0.5 mL, 1.6 mmol) in a 50 mL three-neck flask under N2 flow. The reaction mixture was then dried under vacuum at 110 °C for 1.5 h under stirring (1400 rpm) followed by slow heating (6 °C min−1) to 300 °C (see SI for details, Table S3). Afterward, the temperature was maintained for 20 min followed by the quenching and washing steps as described above for the FeF2 NRs.

Synthesis of Co2P NPs and Co2P NRs

In a typical synthesis of ~3 nm Co2P NPs, “Co(TFA)2” (0.5 g), TOP (10 mL, 22 mmol), and OA (0.5 mL, 1.6 mmol) were loaded into a 50 mL three-neck flask and dried under vacuum at 110 °C for 1.5 h. The reaction mixture was slowly heated to 300 °C at a heating rate of 6 °C min−1 and maintained at this temperature for 1.5 h. The synthesis of Co2P NRs were performed in the same was as that of the Co2P NPs; however, OA was added to the reaction mixtures and the heat-treatment time was prolonged to 2 h. Afterward, the reaction mixtures of Co2P NPs and Co2P NRs were quenched followed by the washing procedure, as described above for the FeF2 NRs.

Synthesis of FeF3 NRs

In a typical synthesis of FeF3 NRs, a ~150 mg portion of the 120 nm long FeF2 NRs in powder form was placed in a closed Al2O3 tube and Al2O3 crucible as a container. The tube was then dried by applying a vacuum for 10 min followed by purging with N2 for 20 min at room temperature. Under an N2 flow, the sample was heated in a tube furnace (Across International, STF1200) to 500 °C. At this temperature, a flow of F2/Ar (Linde, 9.9% of F2 in Ar) gas was set for 10 min. Then, an N2 purge was applied for 30 min, and the tube was cooled down to room temperature. The obtained FeF3 NRs were stored under vacuum. A schematic diagram of the oven set-up is shown in Figure S2.

Powder XRD

Powder diffraction patterns of FeF2 NRs, MnF2 NRs, and Co2P NRs and Co2P NPs were obtained in transmission mode on a Stoe STADI P powder X-ray diffractometer (Cu Kα1 radiation, λ = 1.540598 Å, germanium monochromator). For CoF2 NRs, the patterns were acquired on an STOE IPDS II single crystal diffractometer (image plate detector, a sealed tube with Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.54186 Å, graphite monochromator, monocap-collimator).

HR-, TEM, and SAED

High-resolution (HR) and low-resolution transmission electron microscope (TEM) images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns were taken with a JEOL JEM-2200FS microscope operating at 200 kV. EDX maps in scanning transmission electron microscopy mode were recorded on a probe aberration-corrected FEI Titan Themis operated at 300 kV using a SuperEDX detector with a beam current of about 1 nA. EDX mapping was stopped when degradation of the particles due to radiation damage was observed. Samples for TEM analysis were prepared on carbon-coated Cu grids (Ted-Pella).

EDX

The energy-dispersive x-ray (EDX) spectroscopy measurements were performed on a nanoSEM 230 (FEI).

Electrochemical characterization of FeF2, and FeF3 NRs

FeF2 electrodes were prepared by mixing FeF2 NRs (58%), carbon black (CB, 21%), graphene oxide (GO, 13%), and poly(vinylidene) fluoride binder (pVdF, 8%). First, the ~120 nm long FeF2 NRs were mixed with CB in a ball mill (Pulverisette 7, Fritsch, ZrO2 balls and beaker) for 1 h at 300 rpm followed by a heat treatment at 500 °C for 0.5 h under a N2 atmosphere to remove the ligands and to improve the carbon embedding. Then, the FeF2/CB powder was ball-milled with pre-milled GO (synthesized by the Brodie method42), pVdF, and n-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) for 2 h, at 500 rpm. The final slurry was brushed directly on Al foil and dried under a vacuum at 80 °C for at least 24 h. FeF3 electrodes were prepared following the procedure described above for FeF2 electrodes but without the addition of GO. The composition of the FeF3 slurry was 58% of FeF3 NRs, 34% of CB, and 8% of pVdF. Coin-type cells were assembled in a glovebox with the use of a one-layer glass fiber (Whatman) separator and 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate (1/1 by wt.) electrolyte (300 µL per cell). Li metal served as both a reference and counter electrode. Electrochemical measurements were performed on an MPG2 multi-channel workstation (BioLogic). Prior to electrochemical cycling, the FeF2 and FeF3 electrodes were tested by cyclic voltammetry at scan rates of 0.2 and 0.1 mV s−1 for 5 and 2 cycles, respectively. For galvanostatic measurements of the FeF2 electrodes, constant current-constant voltage (CCCV) mode was applied for discharge and charge steps at 1.5 and 4.0 V vs. Li+/Li. The constant voltage was maintained until the measured current was equal to 1/5 of the initial current value. The obtained capacities were normalized to the mass of the FeF2 or FeF3 NRs.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of transition metal (Fe, Co, Mn) difluoride NPs

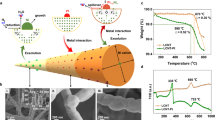

Monodisperse MF2 (M = Fe, Mn, and Co) NRs were obtained by thermolysis of corresponding TMTFAs [“Fe3OTFA”, “Mn(TFA)2”, and “Co(TFA)2”] at temperatures of 250–320 °C with the use of TOP or TOPO as solvents (Fig. 1, see methods and Tables S1–S3 for reaction conditions). As indicated by Blake et al.43, the thermal decomposition of trifluoroacetic anions (TFA−) proceeds via decarboxylation, formation of the trifluoromethyl anion (CF3−), and its subsequent dissociation into a fluoride ion (F−) and difluoromethylene (CF2). Then, F− can couple with a metal ion, resulting in the formation of the corresponding metal fluoride. When the decomposition is performed in a suitable solvent and in the presence of surfactant molecules, the resulting fluorides can adopt the form of uniform colloidal NRs (Fig. 2). In our experiments, the use of TOP and TOPO as solvents was essential for preparing monodisperse MF2 NRs because these act as neutral L-type ligands44, which coordinate to Lewis acidic surfaces. This mechanism might explain the preferred rod morphology of the MF2 NRs; i.e. growth in the [001] direction of the rutile-type crystal structure. The growth in other directions is likely prohibited by TOP/TOPO molecules covering the Lewis acidic, metal-rich (010) and (100) facets of MF2. TOPO likely binds more strongly to the transition metals than does TOP owing to its highly polarized phosphor oxygen bond. Generally, compared with other solvents, such as long-chain alkanes/alkenes, nitrogen and sulfur containing solvents (see example for FeF2 NRs, Figure S3), TOP and TOPO are markedly better solvents for growing MF2 NRs.

Characterization of MF2 (M = Fe, Co, Mn) NRs. (a–f) TEM images of ~200 nm (a) ~120 nm, (b) ~60 nm, (c) ~25 nm, (d) ~15 nm, (e), and (f) ~10 nm FeF2 NRs. (g) Powder XRD patterns of ~120 nm and ~25 nm FeF2 NRs (compared with reference PDF 045–1062) and ~10 nm FeF2 NPs with an asterisk indicating a minor impurity of ~10 nm FeF2 NRs. The impurity can be attributed to the iron oxide (magnetite) layer being present at the surface FeF2 NRs. (h) HRTEM image of ~25 nm FeF2 NR. (i–j) TEM images of MnF2 NRs synthesized in TOP (i) and TOPO (j). (k) TEM image of CoF2 NRs synthesized in TOPO.

Highly crystalline FeF2 NRs were obtained by heating the “Fe3OTFA” precursor solution in TOP solvent to 320 °C (Fig. 1a). The length of the FeF2 NRs was tunable from 10 to 200 nm by addition of OA (Fig. 2a–f, Table S1), presumably because of its stronger bonding to the transition metal-rich facets, such as (010) and (100), than that of TOP solvent. At a low OA content, we also observed twinned, boomerang-shaped FeF2 NRs (Fig. 2c). The heating rate also affected the length of the FeF2 NRs, yielding longer NRs at lower heating rates.

As illustrated in Fig. 2g,h and S4a,b, the powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) images, and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) results confirmed the formation of highly crystalline FeF2 NRs having a tetragonal rutile-type crystal structure with the space group P42/mnm (a = 4.7035 Å, c = 3.3056 Å, V = 73.13 Å3, PDF 045–1062). The FeF2 NRs showed preferred orientation in the powder XRD pattern (Fig. 2g), as indicated by narrower (101) and (002) peaks in comparison with the (110), (111), and (211) reflections; the former being parallel to the growth direction of FeF2 NRs. Additionally, we the (101) and (002) peaks of the FeF2 NRs were more intense than those of bulk FeF2 owing to alignment of the NRs. As the length of the FeF2 NRs decreased, the preferential orientation and texture effects disappeared. We note that TOP is known to be an efficient phosphor source and thus might contaminate FeF2 NRs. From EDX measurements of the FeF2 NRs (Figure S4c), only a tiny amount of phosphorus was detected.

A similar synthetic procedure to that used for FeF2 NRs was applied to MnF2 and CoF2 based on the “Mn(TFA)2” and “Co(TFA)2” precursors, respectively. However, we found slightly different behaviors. First, the choice of the solvent had different effects on the morphology (Fig. 1b, Table S2): 25–35 nm long MnF2 NRs formed in TOP (Fig. 2i) and 15–20 nm long MnF2 NRs formed in TOPO (Fig. 2j). In both solvents, in addition to a tetragonal phase of MnF2 (space group P42/mnm, a = 4.8734 Å, c = 3.3099 Å, V = 78.61 Å3, PDF 075–1717), we observed a high-temperature orthorhombic phase (space group Pbcn; a = 4.96 Å, b = 5.8 Å, c = 5.359 Å, V = 154.17 Å3, PDF 017–0864) (Figures S5, S6); albeit the occurrence of this phase was much more pronounced in the TOPO solvent. EDX measurements of MnF2 NRs synthesized in TOP and TOPO revealed no contamination by phosphorus (Figure S7). The upper temperature of thermolysis was limited to ca. 250 °C because the MnF2 NRs agglomerated into large, cubic particles (~500 nm) at higher temperatures (Figure S8). For CoF2, we synthesized highly crystalline CoF2 NRs in both TOPO (Fig. 2k, Table S3) and TOP solvents (Fig. 3h,i, and Table S3) by thermolysis of “Co(TFA)2” at 300 and 250 °C, respectively. The CoF2 NRs were characterized by tetragonal-, rutile-type crystal structure types (space group P42/mnm; a = 4.7106 Å, c = 3.1691 Å, V = 70.32 Å;3 PDF 033–0417, see Figures S9a,b, S10a). Only a small amount of phosphorous was detected in EDX of CoF2 NRs (Figures S9c, S10b). However, at higher temperatures, thermolysis of “Co(TFA)2” in the presence of TOP, which acts as a phosphor source, yielded Co2P NRs, as discussed in the next section.

(a–h) TEM and HAADF-STEM images of the CoF2 NRs (a–c) and Co2P NRs (d–f) synthesized without OA [inset: HRTEM image of Co2P NRs (scale bar = 4 nm)]. For HAADF-STEM elemental mapping, the following color code was used: cobalt (red), fluorine (yellow) and phosphorous (blue). (g) Synthetic scheme presenting the reaction conditions for obtaining CoF2 and Co2P NRs and Co2P NPs. (h–k) TEM images of CoF2 NRs (h,i) and Co2P NPs (j,k) synthesized with OA.

Synthesis of metal phosphides NRs/NPs

We also found that “Co(TFA)2” might also be used as a precursor for synthesizing cobalt phosphides, when combined with the solvent TOP as a phosphorous source and a solvent with heating to 300 °C (Fig. 1c). TEM analysis and EDX mapping (Fig. 3) point to the following formation mechanism (Fig. 3g): First, “Co(TFA)2” starts to decompose at 250 °C forming CoF2 NRs (Figs 3a–c and S10), which then react with TOP at 300 °C. At this point, we observed a mixture of both cobalt fluoride and cobalt phosphide (Figure S11a,b), followed by the formation of phase-pure 20 nm long cobalt phosphide NRs after 90 min (Fig. 3d–f). The obtained NRs assembled in large 3D clusters owing to their hexagonal shape and narrow size distribution. Our XRD (Figure S12) measurements indicated that the cobalt phosphide NRs crystallized in two different phases: Co2P as the main phase with some CoP, both having the same orthorhombic structure (space group Pnam; for Co2P: a = 5.6465 Å, b = 6.6099 Å, c = 3.513 Å, PDF 032–0306; for CoP: a = 5.077 Å, b = 3.281 Å, c = 5.587 Å, PDF 029–0497).

When OA was added to the reaction mixture of “Co(TFA)2” in TOP, ultra-small 3 nm cobalt phosphide NPs were obtained at 300 °C after 2 h (Fig. 3j,k). The thermolysis of “Co(TFA)2” in TOP with OA for a short reaction time of 0–10 min yielded the mixture of cobalt fluoride and phosphide NRs/NPs (Figure S11c,d). Our XRD and SAED measurements showed that the obtained NPs were amorphous. In addition, small crystalline regions were also visible from high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images (Figure S13). In accordance with the EDX measurements (Figure S13b), the chemical composition of the cobalt phosphide NPs, denoted as Co2P, corresponded to a 2:1 Co:P molar ratio.

We note that the cobalt phosphides have attracted considerable attention over the last three years for their ability to act as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for hydrogen45,46,47,48,49,50,51 and oxygen reduction/evolution reactions52,53,54,55,56,57 with low overpotentials used for water splitting58,59,60,61,62,63,64. These compounds are also used to catalyze substitution reactions of functional groups by hydrogen65,66,67,68,69, for heavy metal removal70,71, and for hydrogenation of CO72. The synthesis of Co2P NRs/NPs based on “Co(TFA)2” as a precursor has not been reported. Importantly, our synthesis of Co2P NRs/NPs yielded a much narrower size distribution than that achieved in NPs synthesized with Co(acac)247,57,73,74,75, ε-Co NPs76, and others precursors77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85.

Synthesis of FeF3 NRs

We tested fluorination of FeF2 NRs with fluorine gas as a route to FeF3 NRs. Briefly, ~120 nm long FeF2 NRs were fluorinated in a powder form at 500 °C with an Ar/F2 gas mixture for 30 min in an aluminum tube (see Experimental Section for details). Our XRD and SAED measurements showed that FeF2 NRs were fully converted to FeF3 NRs (Fig. 4a,b); the latter crystallized in a ReO3-type structure of FeF3 (R-FeF3) with the space group P-3c (167) (a = 5.2 Å and c = 13.323 Å, V = 312 Å3, PDF 033–0647). The rod shape of the initial FeF2 NRs was retained. However, the FeF3 NRs were four times as large as the FeF2 NRs (Fig. 4c) owing to the volume difference between the crystal structures of the FeF2 and R-FeF3. Additionally, agglomeration of R-FeF3 NRs was observed during fluorination caused by concomitant ligand removal from the FeF2 NRs surface. We note that the fluorine gas flow had considerable effects on the complete fluorination of the FeF2 NRs. The temperature was also an important parameter. The formation of R-FeF3 started at a low temperature of 350 °C; however, highly crystalline and phase-pure R-FeF3 NRs were only obtained at 500 °C.

Electrochemical performance of FeF2 and FeF3 NRs

For the electrochemical measurements, we prepared electrodes by mixing a powder of FeF2 or FeF3 NRs with carbon additives [graphene oxide (GO) and/or carbon black (CB)], polyvinylidene fluoride (PVdF), and N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) solvent (see Experimental Section for details). First, the FeF2 or FeF3 NRs were dry ball-milled with GO/CB or CB. Then the resulting powder was subjected to one more step of ball-milling with the pVdF polymer as a binder and NMP as a solvent, followed by casting the slurry onto Al foil. Afterward, the electrodes were dried under vacuum at 80 °C for 24 h.

We tested the FeF2 NRs vs. Li+/Li in the voltage range of 1.5–4.0 V, which includes both conversion and insertion regions. From the CV curves (Fig. 5a), lithiation of electrodes composed of FeF2 NRs during the first discharge was characterized by the appearance of a peak at 2 V vs. Li+/Li associated with reduction of graphene oxide followed by the intensity increase of the negative current at 1.5 V vs. Li+/Li indicating a conversion process of FeF2 NRs (FeF2 + 2Li+ + 2e− → Fe + 2LiF). The formation of Fe and LiF during lithiation of FeF2 has been reported in numerous studies based on in situ86 and ex situ19,87,88,89 methods. In the reverse scan, the FeF2 electrode displayed two peaks at 2.8 and 3.4 V vs. Li+/Li, which are associated with the formation of Li0.5FeF3 and Li0.25FeF3 phases. The third peak at a higher potential of 4.2 V was related to a pronounced and unknown irreversible reaction. Upon further cathodic cycling, a peak at 3.0 V vs. Li+/Li appeared, which we attributed to the formation of a Li0.25FeF3 phase. We note that the intensity increase of CV curves during the initial cycles might be attributed to restructuring processes in the electrode caused by the formation of metallic Fe, which lowers the resistivity of the electrodes. As shown in Fig. 5b, the discharge voltage profiles of the FeF2 NRs were similar to CV curves representing distinct insertion (3.4–2.6 V vs. Li+/Li) and conversion (1.5–2.0 V vs. Li+/Li) reactions. However, upon charging, the galvanostatic curves were rather smooth, which suggested a slow gradual de-lithiation processes.

Electrochemical characterization of FeF2 and FeF3 NRs vs. lithium. Cycling voltammetry of FeF2 (a) and FeF3 (c) NRs at scanning speeds of 0.2 and 0.1 mV s−1, respectively. Galvanostatic charge–discharge curves of FeF2 (b) and FeF3 NRs (d) for 1st, 2nd, and 5th cycles at a current densities of 200 and 50 mA g−1, respectively.

Figure 5c shows cyclic voltammetry curves of the electrodes composed of FeF3 NRs at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1. In the first cathodic cycle (lithiation step), the first two peaks appear at approximately 3.26 and 3.88 V vs. Li+/Li. We attribute these features to electrochemical lithiation of the FeF3 NRs. We note that the mechanism of Li+ intercalation into FeF3 has been examined experimentally and theoretically; however, many of the details remain unclear. It is believed that the initial ReO3-type structure of FeF3 transforms into a tri-rutile-like structure with a composition of Li0.25FeF3 and Li0.5FeF3, which is followed by the formation of FeF2 and LiF (for an overall one-electron process) upon further reduction. In the reverse scan, two distinct reversible de-lithiation reactions of FeF3 NRs are observed suggesting the existence of two prevailing intermediate states of de-lithiated FeF3 (Li0.5FeF3 at ca. 3.1 V and Li0.25FeF3 at ca. 3.3 V), based on studies by Doe et al.90, Yamakawa et al.91, and Li et al.9 Fig. 5d shows the typical voltage profiles of the Li-ion half-cells based on FeF3 NRs as an active material at a current density of 50 mA g−1. The shape of the voltage profiles and the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves, were relatively sharp with a low polarization compared with previously reported data on FeF3 cathodes13,92,93. These results point to an intermittent mechanism of lithiation/de-lithiation of the FeF3 NRs through the formation of intermediate Li0.5FeF3 and Li0.25FeF3 phases. The galvanostatic measurements of FeF2 and FeF3 NRs are presented in Figures S14 and S15, respectively.

Conclusions

This work presents a simple synthetic route to prepare high-quality Fe, Mn, and Co difluoride NRs via thermolysis of transition metal (M = Fe, Mn, and Co) trifluoroacetate complexes in TOP and TOPO solvents. We show that the use of TOP or TOPO solvents is essential for synthesizing monodisperse MF2 NRs, which act as neutral L-type ligands that coordinate to Lewis acidic surfaces leading to the preferred rod morphology (i.e., growth in the [001] direction). The length of the FeF2 NRs was tunable by the addition of oleic acid owing to its stronger bonding to transition metal-rich facets such as (010) and (100). A bottom-up synthesis of high crystalline phase-pure FeF3 NRs by fluorination of our FeF2 NRs by fluorine gas is also reported.

We show that the cobalt trifluoroacetate complex can be thermally decomposed in a TOP solvent system to yield cobalt phosphide NRs/NPs. The reaction mechanism includes: thermolysis of “Co(TFA)2” with the formation of CoF2 NRs following their reaction with TOP at higher temperatures of 300 °C leading to highly monodisperse 20 nm long Co2P NRs or 3 nm Co2P NPs (in the presence of oleic acid).

We also assessed the electrochemical storage of Li+ ions in FeF2 and FeF3 NRs. Our studies are currently underway towards optimization of electrodes composed of FeF2 and FeF3 NRs (e.g., carbon encapsulation) and their electrochemical performance (choice of voltage intervals, and electrolytes).

References

Talapin, D. V., Lee, J.-S., Kovalenko, M. V. & Shevchenko, E. V. Prospects of Colloidal Nanocrystals for Electronic and Optoelectronic Applications. Chem. Rev. 110, 389–458 (2010).

Kovalenko, M. V. et al. Prospects of Nanoscience with Nanocrystals. ACS Nano 9, 1012–1057 (2015).

Bruce, P. G., Scrosati, B. & Tarascon, J.-M. Nanomaterials for Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 47, 2930–2946 (2008).

Oszajca, M. F., Bodnarchuk, M. I. & Kovalenko, M. V. Precisely Engineered Colloidal Nanoparticles and Nanocrystals for Li-Ion and Na-Ion Batteries: Model Systems or Practical Solutions? Chem. Mater. 26, 5422–5432 (2014).

Chen, G., Yan, L., Luo, H. & Guo, S. Nanoscale Engineering of Heterostructured Anode Materials for Boosting Lithium-Ion Storage. Adv. Mater. 28, 7580–7602 (2016).

Peng, Y. et al. Mesoporous Single-Crystal-Like TiO2 Mesocages Threaded with Carbon Nanotubes for High-Performance Electrochemical Energy Storage. Nano Energy 35, 44–51 (2017).

Fang, G. et al. Observation of Pseudocapacitive Effect and Fast Ion Diffusion in Bimetallic Sulfides as an Advanced Sodium-Ion Battery Anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 8 (2018).

Nitta, N., Wu, F., Lee, J. T. & Yushin, G. Li-Ion Battery Materials: Present and Future. Mater. Today 18, 252–264 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Origins of Large Voltage Hysteresis in High-Energy-Density Metal Fluoride Lithium-Ion Battery Conversion Electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2838–2848 (2016).

Yang, Z. H. et al. Atomistic Insights into FeF3 Nanosheet: An Ultrahigh-Rate and Long-Life Cathode Material for Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 3142–3151 (2018).

Badway, F., Cosandey, F., Pereira, N. & Amatucci, G. G. Carbon Metal Fluoride Nanocomposites. J. Electrochem. Soc. 150, A1318–A1327 (2003).

Myung, S. T., Sakurada, S., Yashiro, H. & Sun, Y. K. Iron Trifluoride Synthesized via Evaporation Method and Its Application to Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. J. Power Sources 223, 1–8 (2013).

Ma, R. et al. Large-Scale Fabrication of Graphene-Wrapped FeF3 Nanocrystals as Cathode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. Nanoscale 5, 6338–6343, https://doi.org/10.1039/c3nr00380a (2013).

Yabuuchi, N. et al. Effect of Heat-Treatment Process on FeF3 Nanocomposite Electrodes for Rechargeable Li Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 10035–10041 (2011).

Kim, T. et al. A Cathode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Graphitized Carbon-Wrapped FeF3 Nanoparticles Prepared by Facile Polymerization. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 14857–14864 (2016).

Pereira, N., Badway, F., Wartelsky, M., Gunn, S. & Amatucci, G. G. Iron Oxyfluorides as High Capacity Cathode Materials for Lithium Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 156, A407–A416 (2009).

Osin, S. B., Davliatshin, D. I. & Ogden, J. S. A Study of the Reactions of Fluorine with Chromium and Iron at High Temperatures by Matrix Isolation IR Spectroscopy. J. Fluorine Chem. 76, 187–192 (1995).

Krahl, T., Marroquin Winkelmann, F., Martin, A., Pinna, N. & Kemnitz, E. Novel Synthesis of Anhydrous and Hydroxylated CuF2 Nanoparticles and Their Potential for Lithium Ion Batteries. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 7177–7187 (2018).

Teng, Y. T., Pramana, S. S., Ding, J., Wu, T. & Yazami, R. Investigation of the Conversion Mechanism of Nanosized CoF2. Electrochim. Acta 107, 301–312 (2013).

Bai, Z. et al. The Single-Band Red Upconversion Luminescence from Morphology and Size Controllable Er3+/Yb3+ Doped MnF2 Nanostructures. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 1736 (2014).

Mech, A., Karbowiak, M., Kpiński, L., Bednarkiewicz, A. & Strk, W. Structural and Luminescent Properties of Nano-Sized NaGdF4:Eu3+ Synthesised by Wet-Chemistry Route. J. Alloys. Compd. 380, 315–320 (2004).

Zhou, J., Wu, Z., Zhang, Z., Liu, W. & Dang, H. Study on an antiwear and extreme pressure additive of surface coated LaF3 nanoparticles in liquid paraffin. Wear 249, 333–337 (2001).

Wang, M., Huang, Q.-L., Hong, J.-M. & Chen, X.-T. Controlled synthesis of different morphological YF3 crystalline particles at room temperature. Mater. Lett. 61, 1960–1963 (2007).

Wang, X. & Li, Y. Fullerene-Like Rare-Earth Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 42, 3497–3500 (2003).

Liang, L. et al. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Prismatic NaHoF4 Microtubes and NaSmF4 Nanotubes. Inorg. Chem. 43, 1594–1596 (2004).

Liang, L. et al. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Prismatic NaHoF4 Microtubes and NaSmF4 Nanotubes. ChemInform 35, https://doi.org/10.1002/chin.200420215 (2004).

Zhao, S., Hou, Y., Pei, X., Xu, Z. & Xu, X. Upconversion luminescence of KZnF3:Er3+, Yb3+ synthesized by hydrothermal method. J. Alloys. Compd. 368, 298–303 (2004).

Guan, Q., Cheng, J., Li, X., Ni, W. & Wang, B. Porous CoF2 Spheres Synthesized by a One-Pot Solvothermal Method as High Capacity Cathode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chin. J. Chem. 35, 48–54 (2017).

Rui, K., Wen, Z., Lu, Y., Jin, J. & Shen, C. One-Step Solvothermal Synthesis of Nanostructured Manganese Fluoride as an Anode for Rechargeable Lithium-Ion Batteries and Insights into the Conversion Mechanism. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1401716–1401727 (2015).

Zhang, Y.-W., Sun, X., Si, R., You, L.-P. & Yan, C.-H. Single-Crystalline and Monodisperse LaF3 Triangular Nanoplates from a Single-Source Precursor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 3260–3261 (2005).

Ye, X. et al. Morphologically Controlled Synthesis of Colloidal Upconversion Nanophosphors and Their Shape-Directed Self-Assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 22430–22435 (2010).

Paik, T., Ko, D.-K., Gordon, T. R., Doan-Nguyen, V. & Murray, C. B. Studies of Liquid Crystalline Self-Assembly of GdF3 Nanoplates by In-Plane, Out-of-Plane SAXS. ACS Nano 5, 8322–8330 (2011).

Mai, H.-X. et al. High-Quality Sodium Rare-Earth Fluoride Nanocrystals: Controlled Synthesis and Optical Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6426–6436 (2006).

Du, Y.-P. et al. Single-Crystalline and Near-Monodispersed NaMF3 (M = Mn, Co, Ni, Mg) and LiMAlF6 (M = Ca, Sr) Nanocrystals from Cothermolysis of Multiple Trifluoroacetates in Solution. Chem. Asian J. 2, 965–974 (2007).

Boyer, J.-C., Vetrone, F., Cuccia, L. A. & Capobianco, J. A. Synthesis of Colloidal Upconverting NaYF4 Nanocrystals Doped with Er3+, Yb3+ and Tm3+, Yb33+ via Thermal Decomposition of Lanthanide Trifluoroacetate Precursors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 7444–7445 (2006).

Chan, E. M. et al. Reproducible, High-Throughput Synthesis of Colloidal Nanocrystals for Optimization in Multidimensional Parameter Space. Nano Lett. 10, 1874–1885 (2010).

Mai, H.-X., Zhang, Y.-W., Sun, L.-D. & Yan, C.-H. Size- and Phase-Controlled Synthesis of Monodisperse NaYF4:Yb,Er Nanocrystals from a Unique Delayed Nucleation Pathway Monitored with Upconversion Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 13730–13739 (2007).

Yi, G. S. & Chow, G. M. Synthesis of Hexagonal-Phase NaYF4:Yb,Er and NaYF4:Yb,Tm Nanocrystals with Efficient Up-Conversion Fluorescence. Adv. Funct. Mater 16, 2324–2329 (2006).

Oszajca, M. F. et al. Colloidal BiF3 Nanocrystals: a Bottom-up Approach to Conversion-Type Li-ion Cathodes. Nanoscale 7, 16601–16605 (2015).

Kravchyk, K. V., Zünd, T., Wörle, M., Kovalenko, M. V. & Bodnarchuk, M. I. NaFeF3 Nanoplates as Low-Cost Sodium and Lithium Cathode Materials for Stationary Energy Storage. Chem. Mater. 30, 1825–1829 (2018).

Guntlin, C. P. et al. Nanocrystalline FeF3 and MF2 (M = Fe, Co, and Mn) from Metal Trifluoroacetates and Their Li(Na)-ion Storage Properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 7383–7393 (2017).

Brodie, M. B. C. Sur le Poids Atomique du Graphite. Ann. Chim. Phys. 59, 466–472 (1860).

Blake, P. G. & Pritchard, H. The Thermal Decomposition of Trifluoroacetic Acid. J. Chem. Soc. B: Phys. Org., 282–286 (1967).

Green, M. L. H. A New Approach to the Formal Classification of Covalent Compounds of the Elements. J. Organomet. Chem. 500, 127–148 (1995).

Guo, H. et al. Magnetically Separable and Recyclable Urchin-like Co–P Hollow Nanocomposites for Catalytic Hydrogen Generation. J. Power Sources 260, 100–108 (2014).

Huang, Z. et al. Cobalt Phosphide Nanorods as an Efficient Electrocatalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Nano Energy 9, 373–382 (2014).

Lu, A. et al. Magnetic Metal Phosphide Nanorods as Effective Hydrogen-Evolution Electrocatalysts. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 39, 18919–18928 (2014).

Callejas, J. F., Read, C. G., Popczun, E. J., McEnaney, J. M. & Schaak, R. E. Nanostructured Co2P Electrocatalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction and Direct Comparison with Morphologically Equivalent CoP. Chem. Mater. 27, 3769–3774 (2015).

Cao, S., Chen, Y., Hou, C.-C., Lv, X.-J. & Fu, W.-F. Cobalt Phosphide as a Highly Active Non-Precious Metal Cocatalyst for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production Under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 6096–6101 (2015).

Pan, Y., Lin, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, Y. & Liu, C. Cobalt Phosphide-Based Electrocatalysts: Synthesis and Phase Catalytic Activity Comparison for Hydrogen Evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 4745–4754 (2016).

Ye, C. et al. One-Step CVD Synthesis of Carbon Framework Wrapped Co2P as a Flexible Electrocatalyst for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 7791–7795 (2017).

Chen, K., Huang, X., Wan, C. & Liu, H. Efficient Oxygen Reduction Catalysts Formed of Cobalt Phosphide Nanoparticle Decorated Heteroatom-Doped Mesoporous Carbon Nanotubes. Chem. Commun. 51, 7891–7894 (2015).

Yao, Z. et al. One-Step Synthesis of Nickel and Cobalt Phosphide Nanomaterials via Decomposition of Hexamethylenetetramine-Containing Precursors. Dalton Trans. 44, 14122–14129 (2015).

Doan-Nguyen, V. V. T. et al. Synthesis and Xray Characterization of Cobalt Phosphide (Co2P) Nanorods for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. ACS Nano 9, 8108–8115 (2015).

Dutta, A., Samantara, A. K., Dutta, S. K., Jena, B. K. & Pradhan, N. Surface-Oxidized Dicobalt Phosphide Nanoneedles as a Nonprecious, Durable, and Efficient OER Catalyst. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 169–174 (2016).

Zhong, X. et al. Integrating Cobalt Phosphide and Cobalt Nitride-Embedded Nitrogen-Rich Nanocarbons: High-Performance Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction and Evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 10575–10584 (2016).

Xu, K. et al. Promoting Active Species Generation by Electrochemical Activation in Alkaline Media for Efficient Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution in Neutral Media. Nano Lett. 17, 578–583 (2017).

Jiang, M. et al. New Iron-Based Fluoride Cathode Material Synthesized by Non-Aqueous Ionic Liquid for Rechargeable Sodium Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 186, 7–15 (2015).

Das, D. & Nanda, K. K. One-Step, Integrated Fabrication of Co2P Nanoparticles Encapsulated N, P Dual-Doped CNTs for Highly Advanced Total Water Splitting. Nano Energy 30, 303–311 (2016).

Duan, J., Chen, S., Vasileff, A. & Qiao, S. Z. Anion and Cation Modulation in Metal Compounds for Bifunctional Overall Water Splitting. ACS Nano 10, 8738–8745 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Ultrafine Co2P Nanoparticles Encapsulated in Nitrogen and Phosphorus Dual-Doped Porous Carbon Nanosheet/Carbon Nanotube Hybrids: High-Performance Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 15501–15510 (2016).

Li, W., Zhang, S., Fan, Q., Zhang, F. & Xu, S. Hierarchically Scaffolded CoP/CoP2 Nanoparticles: Controllable Synthesis and Their Application as a Well-Matched Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. Nanoscale 9, 5677–5685 (2017).

Pu, Z. et al. General Strategy for the Synthesis of Transition-Metal Phosphide/N-Doped Carbon Frameworks for Hydrogen and Oxygen Evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 16187–16193 (2017).

Yuan, C.-Z. et al. Direct Growth of Cobalt-Rich Cobalt Phosphide Catalysts on Cobalt Foil: An Efficient and Self-Supported Bifunctional Electrode for Overall Water Splitting in Alkaline Media. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 10561–10566 (2017).

Stinner, C., Prins, R. & Weber, T. Binary and Ternary Transition-Metal Phosphides as HDN Catalysts. J. Catal. 202, 187–194 (2001).

Peng, W. et al. Co2P: A Facile Solid State Synthesis and Its Applications in Alkaline Rechargeable Batteries. J. Alloys. Compd. 511, 198–201 (2012).

Korányi, T. I. Phosphorus Promotion of Ni (Co)-Containing Mo-Free Catalysts in Thiophene Hydrodesulfurization. Appl. Catal., A 239, 253–267 (2003).

Cecilia, J. A., Infantes-Molina, A., Rodriguez-Castellon, E. & Jimenez-Lopez, A. Gas Phase Catalytic Hydrodechlorination of Chlorobenzene over Cobalt Phosphide Catalysts with Different P Contents. J. Hazard. Mater. 260, 167–175 (2013).

Chen, J., Shi, H., Li, L. & Li, K. Deoxygenation of Methyl Laurate as a Model Compound to Hydrocarbons on Transition Metal Phosphide Catalysts. Appl. Catal., B 144, 870–884 (2014).

Ni, Y. et al. Co2P Nanostructures Constructed by Nanorods: Hydrothermal Synthesis and Applications in the Removal of Heavy Metal Ions. New J. Chem. 33, 2055–2059 (2009).

Yuan, F., Ni, Y., Zhang, L., Ma, X. & Hong, J. Rod-Like Co2P Nanostructures: Improved Synthesis, Catalytic Property and Application in the Removal of Heavy Metal. J. Clust. Sci. 24, 1067–1080 (2013).

Song, X. et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Silica-Supported Cobalt Phosphide Catalysts for CO Hydrogenation. Energy Fuels 26, 6559–6566 (2012).

Park, J. et al. Generalized Synthesis of Metal Phosphide Nanorods via Thermal Decomposition of Continuously Delivered Metal-Phosphine Complexes Using a Syringe Pump. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 8433–8440 (2005).

Yang, D. et al. Synthesis of Cobalt Phosphides and Their Application as Anodes for Lithium Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1093–1099 (2013).

Yang, W. et al. A Facile Solution-Phase Synthesis of Cobalt Phosphide Nanorods/Hollow Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 8, 4898–4902 (2016).

Ha, D.-H. et al. The Structural Evolution and Diffusion During the Chemical Transformation from Cobalt to Cobalt Phosphide Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 11498–11510 (2011).

Lukehart, C. M., Milne, S. B., Stock, S. R., Shull, R. D. & Wittig, J. E. Nanocomposites Containing Nanoclusters of Selected First-Row Transition Metal Phosphides. Nanotechnology 13, 195–204 (1996).

Qian, X. F. et al. Organo-Thermal Preparation of Nanocrystalline Cobalt Phosphides. Mater. Sci. Eng. B B49, 135–137 (1997).

Xie, Y., Su, H. L., Qian, X. F., Liu, X. M. & Qian, Y. T. A Mild One-Step Solvothermal Route to Metal Phosphides (Metal = Co, Ni, Cu). J. Solid State Chem. 149, 88–91 (2000).

Hou, H. et al. One-Pot Solution-Phase Synthesis of Paramagnetic Co2P Nanorods. Chem. Lett. 33, 1272–1273 (2004).

Hou, H., Peng, Q., Zhang, S., Guo, Q. & Xie, Y. A “User-Friendly” Chemical Approach Towards Paramagnetic Cobalt Phosphide Hollow Structures: Preparation, Characterization, and Formation Mechanism of Co2P Hollow Spheres and Tubes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 2625–2630 (2005).

Maneeprakorn, W., Malik, M. A. & O’Brien, P. The Preparation of Cobalt Phosphide and Cobalt Chalcogenide (CoX, X = S, Se) Nanoparticles from Single Source Precursors. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 2329–2335 (2010).

Wang, J., Yang, Q., Zhang, Z. & Sun, S. Phase-Controlled Synthesis of Transition-Metal Phosphide Nanowires by Ullmann-Type Reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 7916–7924 (2010).

Zhang, H., Ha, D. H., Hovden, R., Kourkoutis, L. F. & Robinson, R. D. Controlled Synthesis of Uniform Cobalt Phosphide Hyperbranched Nanocrystals using Tri-n-Octylphosphine Oxide as a Phosphorus Source. Nano Lett. 11, 188–197 (2011).

Guo, L., Zhao, Y. & Yao, Z. Mechanical Mixtures of Metal Oxides and Phosphorus Pentoxide as Novel Precursors for the Synthesis of Transition-Metal Phosphides. Dalton Trans. 45, 1225–1232 (2016).

Wang, F. et al. Tracking Lithium Transport and Electrochemical Reactions in Nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 3, 1201 (2012).

Armstrong, M. J., Panneerselvam, A., O’Regan, C., Morris, M. A. & Holmes, J. D. Supercritical-fluid Synthesis of FeF2 and CoF2 Li-ion Conversion Materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 10667–10676 (2013).

Fu, Z.-W. et al. Electrochemical Reaction of Lithium with Cobalt Fluoride Thin Film Electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, E50–E55 (2005).

Rui, K. et al. High-Performance Lithium Storage in an Ultrafine Manganese Fluoride Nanorod Anode with Enhanced Electrochemical Activation Based on Conversion Reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 3780–3787 (2016).

Doe, R. E., Persson, K. A., Meng, Y. S. & Ceder, G. First-Principles Investigation of the Li−Fe−F Phase Diagram and Equilibrium and Nonequilibrium Conversion Reactions of Iron Fluorides with Lithium. Chem. Mater. 20, 5274–5283 (2008).

Yamakawa, N., Jiang, M., Key, B. & Grey, C. P. Identifying the Local Structures Formed during Lithiation of the Conversion Material, Iron Fluoride, in a Li Ion Battery: A Solid-State NMR, X-ray Diffraction, and Pair Distribution Function Analysis Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10525–10536 (2009).

Li, L., Meng, F. & Jin, S. High-capacity lithium-ion battery conversion cathodes based on iron fluoride nanowires and insights into the conversion mechanism. Nano Lett. 12, 6030–6037 (2012).

Tan, J. L. et al. Iron Fluoride with Excellent Cycle Performance Synthesized by Solvothermal Method as Cathodes for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 251, 75–84 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the activities of SCCER HaE, which is financially supported by Innosuisse - Swiss Innovation Agency. The authors are grateful to the research facilities of Empa (Empa Electron Microscopy Center and Laboratory for Mechanics of Materials & Nanostructures) for access to the instruments and for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. C.P.G., K.V.K. and M.V.K. designed the experimental work. C.P.G. synthesized all nanomaterials. R.E. performed TEM measurements. C.P.G. conducted all electrochemical measurements reported in the paper. C.P.G., K.V.K. and M.V.K. wrote the paper. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guntlin, C.P., Kravchyk, K.V., Erni, R. et al. Transition metal trifluoroacetates (M = Fe, Co, Mn) as precursors for uniform colloidal metal difluoride and phosphide nanoparticles. Sci Rep 9, 6613 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43018-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43018-8

This article is cited by

-

Thermal synthesis of conversion-type bismuth fluoride cathodes for high-energy-density Li-ion batteries

Communications Chemistry (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.