Abstract

Bariatric surgery is a treatment option for obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Although sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is growing in favor, some randomized trials show less weight loss and HbA1c improvement compared with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). The study objective was to compare changes in beta-cell function with similar weight loss after SG and RYGB in obese patients with T2DM. Subjects undergoing SG or RYGB were studied with an intravenous glucose tolerance test before surgery and at 5–12% weight loss post-surgery. The primary endpoint was change in the disposition index (DI). Baseline BMI, HbA1c, and diabetes-duration were similar between groups. Mean total weight loss percent was similar (8.4% ± 0.4, p = 0.22) after a period of 21.0 ± 1.7 days. Changes in fasting glucose, acute insulin secretion (AIR), and insulin sensitivity (Si) were similar between groups. Both groups showed increases from baseline to post-surgery in DI (20.2 to 163.3, p = 0.03 for SG; 31.2 to 232.9, p = 0.02 for RYGB) with no significant difference in the change in DI between groups (p = 0.53). Short-term improvements in beta-cell function using an IVGTT were similar between SG and RYGB. It remains unclear if longer-term outcomes are better after RYGB due to greater weight loss and/or other factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is the most effective long-term treatment for obesity and is also considered a treatment option for type 2 diabetes mellitus1. The two most commonly performed bariatric surgeries are Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SG). Although SG is growing in favor2, some randomized clinical trials have shown less weight loss and smaller improvements in HbA1c or use of more diabetes medications to achieve similar glycemic control compared with RYGB3,4,5.

In addition to restriction of gastric capacity, favorable effects of RYGB on T2DM are thought to result from many factors, including hormonal changes, alterations in gastrointestinal transit time, changes in nutrient absorption and possibly changes in serum bile acids and composition of the microbiome6. SG has been less intensively studied but it is believed that many of these factors may also be at play. A major anatomical difference between the two procedures is exclusion of the proximal small intestine with RYGB. Animal studies suggest that duodenal-jejunal bypass improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance independent of changes in body weight, incretin levels, and insulin secretion7,8. Another major anatomical difference for the SG procedure is a complete resection of the stomach fundus, which contains most of the ghrelin producing X/A-like cells9. Thus, consequences of the different anatomical changes may result in differences in insulin sensitivity and secretion that are independent of weight loss.

The objective of the present study was to delineate changes in beta-cell function after SG in patients with T2DM, and to compare these changes to a RYGB cohort after similar weight loss. An intravenous glucose challenge was utilized in order to isolate the change in beta-cell function from differences in nutrient flow between the two procedures.

Methods

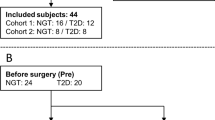

Subjects with T2DM who were planning to undergo SG (N = 10) and RYGB (N = 10), age 18–75 years, and HbA1c 6.5–12% were recruited. Major exclusion criteria included pregnancy; treatment with glucocorticoids, anti-psychotics, neuroleptics, weight loss medications, or a thiazolidinedione; greater than a 5% change in total body weight in the 90 days prior to enrollment in the study; or triglycerides >400 mg/dL.

An insulin supplemented frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (fsIVGTT) was performed prior to and after the intervention as previously described10,11. Initial weight was defined as the weight obtained at the pre-intervention IVGTT visit. The post-intervention IVGTT was performed once the subject had lost 5–12% of body weight. None of the patients experienced complications during the post-operative period of study. Oral diabetes medications were held 2–3 days prior to testing and no patients were on GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy or insulin. Bergman minimal model analysis (MINMOD Millennium 6.02 software) was used to quantify glucose-dependent glucose elimination (Sg), sensitivity of glucose elimination to insulin (Si), acute insulin response to glucose (AIR), and a measure of insulin secretion in relation to insulin sensitivity, the disposition index (DI). Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as reported12. Insulin clearance was calculated using the ratio of fasting C-peptide to insulin13,14. Acute C-peptide response (ACPR) was calculated as the relative mean increase (in percent) in C-peptide levels 3–5 minutes after glucose administration.

Analytic assays

Serum insulin, C-peptide, glucose, total plasma GLP-1, glucagon and total ghrelin were measured as previously described10,14,15.

Statistical Analysis

Power analysis: Based on our prior work10,16, nine subjects in each group would provide 80% probability of detecting a difference of 160 in ΔDI with standard deviation (SD) of 120 for SG versus RYGB with a P α < 0.05%. The primary endpoint was a comparison of the change in DI between groups. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Group differences in the distribution of continuous variables pre-intervention and between-group differences in change from pre to post-intervention were tested with unpaired Student t tests. Within-group differences between pre- and post-intervention were tested with paired Student t tests. All t tests were two tailed. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to evaluate various parameters for group and time interaction. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 7.02.

Ethical Approval, Informed Consent, and Accordance: The study was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Baseline characteristics including mean age (44.0 ± 2.0 years), BMI (45.2 ± 1.4 kg/m²), HbA1c (7.4% ± 0.2), fasting glucose (152.8 ± 10.2 mg/dL), diabetes duration (4.0 ± 0.9 years), and number of diabetes medications (1.5 ± 0.2) were similar between groups (Table 1). No patients were taking insulin or GLP-1 receptor agonists. Weight loss and change in glucose homeostatic parameters are included in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Mean total weight loss percent between groups was similar (8.4% ± 0.4, p = 0.22) after a period of 21.0 ± 1.7 days. Changes in fasting glucose (p = 0.82), AIR (p = 0.43), and Si (p = 0.47) were not different between groups. Both groups showed increases from baseline to post-surgery in DI (20.2 to 163.3, p = 0.03 for SG, and 31.2 to 232.9, p = 0.02 for RYGB) with no significant difference in the change in DI between groups (p = 0.53). Change in DI did not correlate with percent weight loss for the entire cohort (r = −0.05; p = 0.84), or for the groups considered separately. Data were also analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA and no group x time interaction was detected for glucose (p = 0.82), Si (p = 0.47), AIR (p = 0.43) or DI (p = 0.53) values, although time was significant for all these parameters. Insulin clearance increased to a similar degree post-SG and RYGB (p = 0.94).

Changes in plasma hormone levels are presented in Table 3. Ghrelin levels decreased significantly post-op in the SG group but no change was observed after RYGB and there was a significant group difference in the change in ghrelin levels (p < 0.001). GLP-1 levels increased after RYGB (p = 0.07) and decreased after SG (p = 0.06), and the difference in the change in GLP-1 levels between groups was significant (p = 0.01). However, the insulin:GLP-1 molar ratio was also calculated and a similar decrease in this ratio post-SG and RYGB was observed (p = 0.41). There was no significant change in PYY in either group. Glucagon levels decreased to a significant degree post-SG whereas a non-significant increase was observed post-RYGB and the difference in the change in glucagon levels between groups was significant (p = 0.03). However, the change in the insulin:glucagon molar ratio did not differ between groups.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that SG results in a similar short-term improvement in beta-cell function compared with RYGB in subjects with T2DM. After a similar reduction in body weight achieved over the same period of time, improvement in DI was nearly identical between the two procedures. Differences in the change in secondary outcomes, including fasting glucose, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion were also not observed. These results suggest that the anatomical differences between the two procedures do not modify the intrinsic improvement in beta-cell function at this early post-operative period although it is important to note that an intravenous instead of an oral nutrient challenge was utilized in order to eliminate potential confounding factors related to altered nutrient flow.

Our results are in agreement with a study by Bradley et al. that demonstrated similar improvements in insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function using a hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp procedure after a matched 20% weight loss in subjects without T2DM17. In contrast, using a hyperglycemic clamp, Kashyap et al. compared RYGB with laparoscopic adjustable band (LAGB) and SG in patients with obesity and T2DM at one and four weeks after surgery and found that insulin sensitivity improved only in the RYGB group18. However, these results are difficult to interpret given that SG was not studied independent of LAGB, which has been shown to be a somewhat inferior metabolic surgery for the treatment of T2DM19.

Basso et al. evaluated very early changes in glycemic parameters and gut hormones in subjects with obesity and T2DM using an IVGTT three days after SG and found a significant increase in insulin secretion and a significant improvement in peripheral insulin sensitivity in subjects with diabetes for less than 10.5 years20. A reduction in ghrelin, increase in GLP-1 (both basal and 15 minutes after glucose infusion), and increase in glucose-stimulated PYY post-op were observed after SG. The authors proposed a “gastric hypothesis” in which an extra-pancreatic and/or extra-intestinal factor that inhibits insulin secretion may be produced in the stomach and excision of the gastric fundus in SG removes this “factor” and improves insulin secretion. In our study, there is no additional evidence of a negative gastric factor (anti-incretin or anti-insulin sensitivity factor) with IV stimulus or in the fasting state as the results for RYGB and SG were similar.

Changes in insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function have been compared after RYGB and SG using an oral meal challenge. In agreement with our findings, Wallenius et al. found similar improvements in glucose control and insulin secretion using a modified 30 g oral glucose tolerance test (MOGTT) 2 days, 3 weeks, and 1 year after SG and RYGB, despite a significantly greater weight loss and increase in GLP-1 with RYGB at 1 year21. At 15 days after RYGB or SG, Nannipieri et al. found that both SG and RYGB groups showed similar increased insulin secretion rates and modest improvements in beta-cell sensitivity22. At 1 year, after marked weight loss, which was somewhat more after RYGB (p = 0.09), similar improvements in glycemic control, diabetes remission, insulin sensitivity, and beta-cell glucose sensitivity were observed. Romero et al. reported that at 4–6 weeks post-surgery with similar weight loss, both SG and RYGB groups showed similar improvements in glucose tolerance and DI23. At two years post-op in a metabolic substudy of the STAMPEDE trial, Kashyap et al. reported marked improvements in beta-cell function (oral DI) after RYGB and only negligible improvement after SG with similar weight loss24. However, there was not a statistical difference between groups in change in DI (p = 0.34) or change in insulin sensitivity (p = 0.39).

Our results indicate a similar improvement in fasting hepatic insulin clearance post- RYGB and SG, suggesting the liver plays a role in the early improvement in glycemic control. Our findings are in agreement with Immonen et al. who demonstrated improvements in several hepatic glycemic parameters, including insulin clearance in a combined SG and RYGB group at 6 months post-op25.

We cannot exclude the possibility that factors unique to each procedure result in independent mechanisms by which improvements in glycemic control are achieved, particularly after a nutrient challenge. In RYGB, exclusion of the proximal small intestine may result in a greater improvement in insulin secretion due to the nutrient exclusion from the proximal small intestine and rapid delivery of unabsorbed nutrients to the distal small intestine which is thought to enhance the secretion of GLP-1 and PYY6, whereas the role of GLP-1 after SG has been less well studied26. There is evidence of accelerated gastric emptying after SG shown in scintigraphy studies27, which may be followed by delayed small intestinal transit. These factors may conceivably enhance postprandial GLP-1 and PYY release after SG as well. In the present study, fasting levels of GLP-1 and PYY did not change significantly post-SG or RYGB; however we did not assess post-prandial glucose or gut hormone levels given our experience of patients feeling ill after a significant oral nutrient load in this early post-operative period.

Due to the resection of the gastric fundus, fasting ghrelin levels post-SG were significantly reduced, whereas there was no change post-RYGB. It appears this preferential decline in ghrelin post-SG is durable out to at least 18 months28. The reduction in ghrelin levels after SG may enhance insulin secretion29 and insulin sensitivity30. A reduction in glucagon was observed only post-SG. However, the insulin:glucagon molar ratio decreased to a similar extent in both groups, suggesting a relative hyperglucagonemia after both surgeries. In the Diabetes Surgery Study, we found a similar change in the insulin:glucagon molar ratio after RYGB, but no significant change after intensive medical management14. The relative hyperglucagonemia after both SG and RYGB may be important for the metabolic benefits31.

It is also likely that in the longer-term RYGB may provide additional benefits compared with SG as was shown in the STAMPEDE trial in which there was greater weight loss and an equivalent improvement in HbA1c achieved after 5 years with the use of fewer diabetes medications5. The extent to which differences in weight loss impact the different outcomes seen with these procedures is unclear. We have previously shown that improvement in HbA1c correlates with the percent weight loss one year after RYGB14. In this study, there was no correlation between change in DI and weight loss, however, the range of weight loss was likely too narrow and the profound caloric restriction at this early time-point may supersede the ability to detect the weight loss effect.

A major strength of this study is that groups were well matched not just for baseline characteristics, but importantly, they were also matched for weight loss and duration of the post-operative period of study. However, limitations of this study include the nonrandomized design, the relatively small sample size and assessment of only short-term changes. Additionally, we did not assess post-prandial glucose or gut hormone levels. While it has been shown that there are important changes in fasting gut peptide levels after SG and RYGB20,32,33,34, it is important to acknowledge that results might differ if beta-cell function and gut hormone changes were assessed using an oral nutrient challenge. Finally, our study did not include a diet-induced weight loss control group and caloric restriction is known to independently improve glycemic control35. At the post-operative study visit, SG and RYGB subjects were on a pureed diet of approximately 500 kcal/day and this degree of caloric restriction likely plays a role in the observed early improvements in diabetes. We did compare the SG group to a similar cohort of subjects with diabetes placed on a very low calorie diet as previously reported10 (data not shown) and similar improvements in beta-cell function were also observed. Our findings suggest that some of the early improvements in diabetes in both the SG and RYGB groups may be a consequence of caloric restriction and weight loss, rather than mechanisms unique to a bariatric procedure. However, from several randomized controlled clinical trials it has become clear that clinically surgery produces greater and more durable improvements in glycemic control4,5,36,37. We cannot determine from this study whether differences between these procedures would be observed if subjects were studied at equivalent weight loss at a later post-operative period once caloric intake is liberalized.

Conclusions

SG improves beta-cell function as well as RYGB in the short term in obese patients with T2DM when assessed using an IV glucose challenge. However, further studies are needed to determine if longer-term clinical outcomes tend to be better after RYGB due to greater weight loss and/or other factors that differ between the procedures as a consequence of the different anatomical alterations.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dixon, J. B., Zimmet, P., Alberti, K. G. & Rubino, F. Bariatric surgery: an IDF statement for obese Type 2 diabetes. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 55, 367–382 (2011).

Buchwald, H. & Oien, D. M. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 23, 427–436, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0864-0 (2013).

Lee, W. J. et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg 146, 143–148, https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2010.326 (2011).

Schauer, P. R., Bhatt, D. L. & Kashyap, S. R. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes. N Engl J Med 371, 682, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1407393 (2014).

Schauer, P. R. et al. Bariatric Surgery versus Intensive Medical Therapy for Diabetes - 5-Year Outcomes. N Engl J Med 376, 641–651 (2017).

Nguyen, K. T. & Korner, J. The sum of many parts: potential mechanisms for improvement in glucose homeostasis after bariatric surgery. Curr Diab Rep 14, 481, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-014-0481-5 (2014).

Salinari, S., le Roux, C. W., Bertuzzi, A., Rubino, F. & Mingrone, G. Duodenal-jejunal bypass and jejunectomy improve insulin sensitivity in Goto-Kakizaki diabetic rats without changes in incretins or insulin secretion. Diabetes 63, 1069–1078, https://doi.org/10.2337/db13-0856 (2014).

Rubino, F. et al. The mechanism of diabetes control after gastrointestinal bypass surgery reveals a role of the proximal small intestine in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Ann Surg 244, 741–749, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000224726.61448.1b (2006).

Castaneda, T. R., Tong, J., Datta, R., Culler, M. & Tschop, M. H. Ghrelin in the regulation of body weight and metabolism. Front Neuroendocrinol 31, 44–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.10.008 (2010).

Jackness, C. et al. Very low-calorie diet mimics the early beneficial effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on insulin sensitivity and beta-cell Function in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 62, 3027–3032, https://doi.org/10.2337/db12-1762 (2013).

Welch, S., Gebhart, S. S., Bergman, R. N. & Phillips, L. S. Minimal model analysis of intravenous glucose tolerance test-derived insulin sensitivity in diabetic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 71, 1508–1518, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-71-6-1508 (1990).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419 (1985).

Bojsen-Moller, K. N. et al. Increased hepatic insulin clearance after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98, E1066–1071, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-1286 (2013).

Nguyen, K. T. et al. Preserved Insulin Secretory Capacity and Weight Loss Are the Predominant Predictors of Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Randomized to Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Diabetes, https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-1870 (2015).

Korner, J. et al. Effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on fasting and postprandial concentrations of plasma ghrelin, peptide YY, and insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90, 359–365, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1076 (2005).

Plum, L. et al. Comparison of Glucostatic Parameters After Hypocaloric Diet or Bariatric Surgery and Equivalent Weight Loss. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19, 2149–2157, https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.134 (2011).

Bradley, D. et al. Matched weight loss induced by sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass similarly improves metabolic function in obese subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22, 2026–2031, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20803 (2014).

Kashyap, S. R. et al. Acute effects of gastric bypass versus gastric restrictive surgery on beta-cell function and insulinotropic hormones in severely obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Obes (Lond) 34, 462–471, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2009.254 (2010).

Rubino, F., Schauer, P. R., Kaplan, L. M. & Cummings, D. E. Metabolic surgery to treat type 2 diabetes: clinical outcomes and mechanisms of action. Annu Rev Med 61, 393–411, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.051308.105148 (2010).

Basso, N. et al. First-phase insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity, ghrelin, GLP-1, and PYY changes 72 h after sleeve gastrectomy in obese diabetic patients: the gastric hypothesis. Surg Endosc 25, 3540–3550, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1755-5 (2011).

Wallenius, V. et al. Glycemic Control after Sleeve Gastrectomy and Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass in Obese Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Obes Surg, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-3061-3 (2017).

Nannipieri, M. et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: mechanisms of diabetes remission and role of gut hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98, 4391–4399, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-2538 (2013).

Romero, F. et al. Comparable early changes in gastrointestinal hormones after sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-En-Y gastric bypass surgery for morbidly obese type 2 diabetic subjects. Surg Endosc 26, 2231–2239, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2166-y (2012).

Kashyap, S. R. et al. Metabolic effects of bariatric surgery in patients with moderate obesity and type 2 diabetes: analysis of a randomized control trial comparing surgery with intensive medical treatment. Diabetes Care 36, 2175–2182, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-1596 (2013).

Immonen, H. et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on liver glucose metabolism in morbidly obese diabetic and non-diabetic patients. J Hepatol 60, 377–383, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.012 (2014).

Smith, E. P., Polanco, G., Yaqub, A. & Salehi, M. Altered glucose metabolism after bariatric surgery: What’s GLP-1 got to do with it? Metabolism, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2017.10.014 (2017).

Shah, S. et al. Prospective controlled study of effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on small bowel transit time and gastric emptying half-time in morbidly obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Surg Obes Relat Dis 6, 152–157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2009.11.019 (2010).

Alamuddin, N. et al. Changes in Fasting and Prandial Gut and Adiposity Hormones Following Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y-Gastric Bypass: an 18-Month Prospective Study. Obes Surg 27, 1563–1572, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2505-5 (2017).

Tong, J. et al. Physiologic concentrations of exogenously infused ghrelin reduces insulin secretion without affecting insulin sensitivity in healthy humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98, 2536–2543, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-4162 (2013).

Vestergaard, E. T. et al. Acute effects of ghrelin administration on glucose and lipid metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93, 438–444, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-2018 (2008).

Jall, S. et al. Monomeric GLP-1/GIP/glucagon triagonism corrects obesity, hepatosteatosis, and dyslipidemia in female mice. Mol Metab 6, 440–446 (2017).

Korner, J. et al. Prospective study of gut hormone and metabolic changes after adjustable gastric banding and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Int J Obes (Lond) 33, 786–795 (2009).

Beckman, L. M., Beckman, T. R. & Earthman, C. P. Changes in gastrointestinal hormones and leptin after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure: a review. J Am Diet Assoc 110, 571–584 (2010).

Karamanakos, S. N., Vagenas, K., Kalfarentzos, F. & Alexandrides, T. K. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, double blind study. Ann Surg 247, 401–407, https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318156f012 (2008).

Kelley, D. E. et al. Relative effects of calorie restriction and weight loss in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 77, 1287–1293, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.77.5.8077323 (1993).

Ikramuddin, S. et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for diabetes (the Diabetes Surgery Study): 2-year outcomes of a 5-year, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 3, 413–422 (2015).

Pournaras, D. J. et al. Improved glucose metabolism after gastric bypass: evolution of the paradigm. Surg Obes Relat Dis 12, 1457–1465, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.020 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Princess Swan for assistance with sample preparation and hormone analysis and the nursing staff at the CTSA for assistance with performance of study procedures. This study was funded by Grant UL1-TR000040 and Grant UL1-RR024156 to Columbia University, both from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), formerly the National Center for Research Resources; NIH DK-072011; and T32DK007271-36A1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. was responsible for data management and analysis, performance of study procedures and manuscript preparation. G.F. was responsible for patient recruitment and performance of study procedures. M.B. assisted with patient recruitment. J.K. conceived and designed the study, supervised the experiments, managed the data and analysis, and participated in manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

Dr. Mullally has received research funding from the NIH. Dr. Korner has received research funding from the NIH and has stock options in Digma Medical. Dr. Febres and Dr. Bessler declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mullally, J.A., Febres, G.J., Bessler, M. et al. Sleeve Gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Achieve Similar Early Improvements in Beta-cell Function in Obese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Sci Rep 9, 1880 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38283-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38283-y

This article is cited by

-

Low-Grade Hepatic Steatosis Is Associated with Long-term Remission of Type 2 Diabetes Independent of Type of Bariatric-Metabolic Surgery

Obesity Surgery (2023)

-

Revisional large gastric pouch with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for patients with type 2 diabetes and a body mass index less than 35 kg/m2: a cause and effect analysis

Surgery Today (2022)

-

Changes induced by metabolic surgery on the main components of glucose/insulin system in patients with diabetes and obesity

Acta Diabetologica (2021)

-

Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy on Static and Dynamic Measures of Glucose Homeostasis and Incretin Hormone Response 4-Years Post-Operatively

Obesity Surgery (2020)

-

Bariatrische Chirurgie bei Typ-2-Diabetes

Der Diabetologe (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.