Abstract

Diet and exercise are conventional methods for controlling body weight and are linked to alterations in gut microbiota. However, the associations of diet, exercise, and gut microbiota in the control of obesity remain largely unknown. In the present study, using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), normal fat diet (NFD), exercise and their combination resulted in improved metabolic profiles in comparison to sedentary lifestyle with high fat diet (HFD). Moreover, diet exerted more influence than exercise in shaping the gut microbiota. HFD-fed mice receiving FMT from NFD-exercised donors not only showed remarkably reduced food efficacy, but also mitigated metabolic profiles (p < 0.05). The transmissible beneficial effects of FMT were associated with bacterial genera Helicobacter, Odoribacter and AF12 and overrepresentation of oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis genes. Our findings demonstrate that the beneficial effects of diet and exercise are transmissible via FMT, suggesting a potential therapeutic treatment for obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The gut microbiota plays an important role in human metabolism, and an imbalance in its composition (i.e., dysbiosis) has been associated with obesity and other metabolic abnormalities. It is influenced by several factors and its modification can alter host adiposity via different mechanisms1,2. In keeping with empirical evidence that normal diet and exercise are beneficial to human health, especially in terms of weight control, emerging data have linked dietary interventions and exercise to altered gut microbiota in obese mice3,4 and professional athletes5, suggesting that gut microbiota mediates the beneficial physiological outcomes of diet and exercise.

Gut microbiota resulting from normal diet, in which there is reduced caloric intake, has been reported to ameliorate metabolic disturbance in murine models with obesity3,6,7. Microbial mechanisms underlying the detrimental effects of high fat diet (HFD) have also been postulated largely in mouse models. At first, HFD causes microbial dysbiosis in the gut (for example, by promoting the growth of opportunistic pathogens8), altering intestinal integrity9,10 (i.e., leaky gut), which results in endotoxemia and ultimately obesity11. The association between HFD and endotoxemia was also shown in healthy human subjects12,13. Previous studies have sequentially linked HFD to obesity through the effects of the gut microbiota.

In mouse models, exercise increases caloric consumption and alters the gut bacterial community, attenuating some obesity-related changes4,14. These results shed new light on obesity management. In addition to the established hormonal alterations in humans (e.g., peptide YY15 and ghrelin16) that reduce appetite, exercise in rats supposedly alters gut microbiota and increases butyrate concentration in the cecum17. In humans, butyrate is known to reduce inflammation through NF-κB inhibition18, and its beneficial effects on host insulin sensitivity19 and immunity20 were shown in mice. Several mechanisms by which exercise modifies gut microbiota have been proposed. For example, exercise-induced stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and causes the release of various hormones (e.g., corticotropin, noradrenaline, and serotonin), which impact the gastrointestinal environment and alter the gut microbiota21. Exercise also reduces human gut transit time22 and changes stool consistency, which has been shown to be strongly associated with human gut microbial composition23,24. Although prolonged vigorous exercise can cause impaired intestinal permeability25, highly trained athletes have been found to have lower levels of blood endotoxin26, suggesting that chronic physical training improves gut barrier integrity.

Despite the myriad of studies on the beneficial effects of normal diet and exercise on obesity and corresponding alterations in the gut microbiota, little is known about their joint effects in the control of obesity. In addition, whether fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) can transmit the beneficial effects of diet and exercise to alter metabolic profiles has not been investigated.

Here, we show that the weight reducing effects of normal diet and exercise, and related improvements in metabolic and inflammatory profiles, are transmissible via FMT. Our findings highlight the critical role of the gut microbiota in obesity and suggest that FMT from donors with balanced diet or regular workout (or in combination) is of potential benefit to recipients in terms of altering metabolic and inflammatory profiles.

Results

According to diet type, exercise and FMT status, mice were divided into seven groups. Treatment naïve groups included H and N, representing mice fed with high fat diet (HFD) and normal fat diet (NFD), respectively. HE and NE refer to mice receiving HFD and NFD, respectively, and undergoing exercise regimen. H_FHE group consisted of H mice receiving FMT by gavage from HE donor and H_FNE and N_FNE groups consisted of H and N mice, respecitvely, receiving FMT from NE donor (Fig. 1). Details of study design and animal model are presented in the Methods section.

Schematic representation of study design. Seven groups of mice were defined in this study. Abbreviations indicate treatments: H, sedentary mice fed high fat diet (n = 6); HE, exercised H mice (n = 7); N, sedentary mice fed normal fat diet (n = 7); NE, exercised N mice (n = 6); H_FHE: H mice receiving FMT from HE (n = 7); H_FNE, H mice receiving FMT from NE (n = 7); N_FNE: N mice receiving FMT from NE (n = 7). Icon with number indicates FMT donor group; 2 refers to HE and 6 refers to NE.

Diet and exercise altered mice metabolism

There were no significant differences in food consumption between FMT recipients (i.e., H_FHE, H_FNE and N_FNE) (p > 0.05, t-test) and their non-FMT counterparts fed the same diet (Fig. 2A), which suggested that gavage merely affects recipients’ feeding behavior. Reductions in food efficacy (i.e., grams of body weight gain per 100 g food consumed) were greatest in H_FNE (34.8% compared to H) followed by HE (21.5%) among mice fed HFD and were similar among NFD-fed mice (Fig. 2B).

Food consumption and efficacy of each group. (A) Food consumption per group was recorded weekly. Data were adjusted to n = 7 and compared between non-FMT and FMT recipient groups and p values (t-test) were obtained. (B) Food efficacy of each group was estimated as grams of body weight gain per 100 g food consumed. Data are shown in the figure.

The FMT recipient mice underwent a two-day antibiotics regimen before the experiment started (see Methods) to ensure that the outcomes are compatible with clinical guidelines for FMT in humans27. As antibiotics increase host susceptibility to obesity28, to verify this effect, a supplementary experiment that compared body weight gain and IPGTT results of HFD-fed mice with and without antibiotics exposure was performed (Supplementary file: Supplementary Note 1). There was no significant difference in body weight gain, but glucose tolerance increased significantly (p = 0.023, Student’s t-test) in HFD-fed mice with antibiotics exposure (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), indicating that the FMT recipient mice herein are more susceptible to obesity phenotypes compared to those not exposed to antibiotics.

With regard to the body weight, there were significant differences among groups (p < 2 × 10−16, two-way ANOVA). H_FNE mice exhibited parallel weight reduction to HE mice (Fig. 3A), in comparison with H group. To better delineate the central tendency of the data, metabolic parameters and gene expression data were compared using a 5%-truncated mean (see Methods). Compared with H mice, N, HE and H_FNE groups demonstrated significant reduction in fat weight, as well as in blood parameters including fasting blood glucose, IPGTT, ALT and LDL (Fig. 3B–I). HE, H_FHE, H_FNE and N_FNE mice also demonstrated lower Il1a expressions compared with H mice, while only HE mice showed a lower Pparg expression (Fig. 3F–G). Detailed data are shown in Supplementary Table 3 (Supplementary file), and IPGTT curves for each group are in Supplementary Fig. 2 (Supplementary file).

Physiological parameters and inflammatory gene expressions in mice. (A) Body weights of all mice involved in the experiment were measured weekly. Data are expressed as mean ± SE per group. (B–I) Metabolic and inflammatory parameters are expressed as 5% truncated means (data within 5–95% quantile) ± SE. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (Student’s t-test, vs. H). Data points are shown in semi-transparency. IPGTT was measured monthly and the measurement at the end of experiment is presented. Other parameters and gene expression levels were determined after mice were euthanized. IPGTT, intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test; Tnf, tumor necrosis factor gene; Il1a, interleukin 1 alpha gene; Pparg, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma gene; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; LDL, low density lipoprotein.

To confirm the effectiveness of HFD, which is associated with lipid accumulation in liver29,30, mice liver and fat pad tissues were examined by histological staining and compared among the groups. The results demonstrated that fat deposition in liver tissue and adipocyte size in fat pad tissues were reduced in normal diet and exercised groups (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 3).

Diet and exercise exerted differential effects on gut microbiota

Gut microbial compositions were assessed by fecal 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing and statistically analyzed. On principal coordinates analysis (PCoA), the gut microbiota of the groups were separate from each other (p < 0.001, Monte-Carlo simulation). Diet was more influential than exercise in shaping the gut microbiota, as demonstrated by greater separation among groups based on diet than among groups based on exercise status (Fig. 4A) and verified by 2-way PERMANONA (diet: R2 = 0.297, p = 0.001; exercise: R2 = 0.098, p = 0.001). A similar outcome was obtained by linear modeling of Shannon index, which showed diet as the most important factor associated with microbiota diversity (p = 3.26 × 10−7) (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 4).

Principal coordinates analysis of mice gut microbiota. PCoA was conducted based on Bray–Curtis distance of operational taxonomic unit (OTU) relative abundance in mice gut microbiota. Groups are distinguished by colors. The significance (p value) of between-group inertia was evaluated by Monte-Carlo test (with 1000 permutations). (A) PCo ordination of mice gut microbiota before FMT. (B) PCo ordination of mice gut microbiota after FMT.

Beneficial effects of diet and exercise were transmissible through FMT

To examine whether the effects of normal diet and exercise on host metabolism and inflammation are transmissible, FMT experiments were conducted by dividing the mice into three groups: H_FHE, H_FNE and N_FNE (Fig. 1). Results indicated that FMT from NE group donors (H_FNE) has comparable effect to exercise in reducing body and fat weight in HFD group (Fig. 3A,B). FMT from HE donors (H_FHE) also led to significant weight reduction, but was not as effective as FMT from NE donors. With respect to blood parameters and inflammatory cytokine levels, both H_FHE and H_FNE exhibited improved outcomes comparable to those of HE (Fig. 3C–I).

To validate the interaction between the gut microbiota and their transmissible effect on host metabolism, gut microbial compositions before and after FMT were compared (Fig. 4). Among NFD mice, the gut microbiota of N_FNE group was similar to that of N group before FMT and to that of NE group after FMT. Among HFD mice, the H_FHE and H_FNE gut microbiota overlapped with that of H group before FMT, while they shifted towards HE group after FMT (Fig. 4B). It is interesting to note that the H_FNE group harbored similar microbial composition to the HE group, but not to the NE group, after FMT, suggesting that the beneficial effect of exercise is transmissible via FMT and that colonization of transferred microbes depends on the recipient’s diet.

Genera associated with exercise and diet in FMT recipients

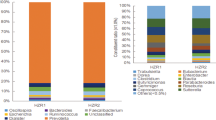

The specific alterations in gut microbiota associated with the beneficial effects of diet and exercise were further resolved based on linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe). When stratified by diet, Turicibacter, Sutterella, Prevotella, AF12 and Helicobacter comprised the top five genera in N and NE groups when compared with H and HE groups (Fig. 5A). When stratified by exercise, Odoribacter, AF12, Helicobacter, and Akkermansia represented the top genera in HE and NE groups when compared with H and N groups (Fig. 5B). Odoribacter, Helicobacter and AF12 were the top three genera in FMT groups when compared with non-FMT groups (Fig. 5C). The LEfSe results of comparisons among FMT donors and recipients (i.e., HE vs. H_FHE, NE vs. H_FNE and NE vs. F_FNE) are available in Supplementary Fig. 5 (Supplementary file).

Top genera based on LEfSe and stratified by diet, exercise and FMT. Based on the genera relative abundance after FMT (i.e., week 24), the top 5 genera in each LEfSe comparison (p < 0.05) were obtained. The log-2 ratio of genus average relative abundance is presented as x-axis and genus names are presented as inlet. (A) Genera in LEfSe comparisons stratified by diet. (B) Genera in LEfSe comparisons stratified by exercise. (C) Genera in LEfSe comparisons stratified by FMT. NA, not applicable; avg., average; rel., relative; abd., abundance.

Predicted functional genes associated with exercise

Prompted by the results that both diet and exercise contributed to the microbiota alteration (Fig. 4A) and the well-established sequence of gut microbiota transformed by diet31, we investigated the functional genes associated with exercise. As N and NE were shown to share similar phenotypical outcomes (Fig. 3), H and HE mice before FMT were compared to identify those genes differentially enriched by exercise. Among 1250 clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) of significant overabundance (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p < 0.05) in HE, 93 were related to energy production and 57 to carbohydrate metabolism (Supplementary file: Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), which are functions closely associated with physiological changes induced by exercise.

Genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation were overabundant in the HE gut microbiota, particularly protein complexes in electron transport chain (Supplementary file: Supplementary Table 4) such as Na+-transporting NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (COG1347, COG1726, COG1805, COG2209, COG2869 and COG2871), NADH dehydrogenase (COG1252), NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (COG0377, COG0649, COG0713, COG0838, COG0839, COG1005, COG1007 and COG1008), succinate dehydrogenase (COG0479, COG1053 and COG2009), cytochrome c1 (COG2857), cytochrome c2 (COG3474) and ATP synthase (COG0055, COG0056, COG0355, COG0356 and COG0712). There were also other respiratory enzymes driving oxidative phosphorylation, including lactate dehydrogenase (COG0039 and COG1052), nitrate reductase (COG2181 and COG3005) and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (COG0240 and COG0578).

In line with the enrichment of genes associated with oxidative phosphorylation, COGs related to glycolysis were also more abundant in HE (Supplementary file: Supplementary Table 5) including 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (COG0126), 6-phosphofructokinase (COG0205), fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (COG1830), enolase (COG0148), glucokinase (COG0837), phosphoglycerate mutase (COG0588), pyruvate kinase (COG0469) and triosephosphate isomerase (COG0149).

Discussion

In this study, we found that diet and exercise interact to alter metabolic markers, inflammatory profiles, and gut microbial composition in mice. Diet played a more important role than exercise in shaping the gut microbiota. We also demonstrated that the beneficial effects of normal diet and exercise can be transmitted via FMT to improve metabolism and inflammatory status in obesity. Finally, we identified several specific microbes associated with this transmissible beneficial effect.

The antibiotics regimen for FMT recipient mice increased their susceptibility to obesity phenotype (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 1). As H_FNE and H_FHE groups exhibited significant reductions in body and fat weight, and improvements in metabolic profiles compared with H group, the beneficial effects of FMT from exercised donors exceedingly counteracted the predisposition to obesity caused by HFD and antibiotics. Therefore, the beneficial effects are potentially even greater than if antibiotics were not used. Last but not least, the larger reduction in food efficacy of H_FNE than H_FHE (Fig. 2B) suggested that transplanted NE microbiota contributed more to the beneficial effects than transplanted HE microbiota.

In terms of diet, ingested food directly interacts with gut microbes and serves as their cultivation medium. Exercise elicits varied physiological responses based on duration and intensity, leading to less predictable microbial fluctuations. These substantial differences in the effects of diet and exercise on the gut microbial community potentially explain our observations that diet is more influential than exercise in altering the gut microbiota.

Bacterial components are known to alter host metabolism and to induce chronic inflammation that underlies obesity. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide9,11 and peptidoglycan32 represent two classic examples accounting for obesity-related insulin resistance during metabolic endotoxemia, by activating Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing (NOD) proteins (NOD133,34,35 and NOD236,37), respectively. Therefore, a supplementary experiment probing the expression level of Tlr4, Nod1 and Nod2 was performed to see the associations between metabolic endotoxemia and FMT (Supplementary file: Supplementary Note 2). Although it was with marginal significance, the lower gene expressions of Tlr4 (p = 0.138, t-test vs. H), Nod1 (p = 0.104, t-test vs. H) and Nod2 (p = 0.125, t-test vs. H) in HE compared to H suggested that exercise apparently reduces metabolic endotoxemia (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 6). This result agreed with previous findings in Korean women38. Among FMT recipients, the reduced expressions of Tlr4 and Nod2 compared to H reflected lower inflammation (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 6), implying that their improved metabolism might associate with the mitigated endotoxemia by receiving FMT from exercised donors. The unaffected expression of Nod1 requires further exploration.

In agreement with the results of previous studies in murine models39,40, the Akkermansia and Lactobacillus genera were more abundant in exercised mice fed NFD. The increased relative abundance of SMB53 in H rather than N group was consistent with its positive correlation with host adiposity in rats41. In addition, the observed increases in Turicibacter and Prevotella proportion in N compared with H mice were in line with their depletion in HFD-fed mice42. With respect to changes in taxa by FMT, the overlap among genera of significant contrasting abundance in FMT recipients (i.e., H_FHE, H_FNE and N_FNE) demonstrated that Helicobacter, Odoribacter and AF12 are highly associated with FMT from exercised donors. AF12 exhibited about a 100-fold increase in HFD-fed recipients (Supplementary file: Supplementary Table 7). Helicobacter and Odoribacter demonstrated 2–3 orders of magnitude higher abundance in HFD-fed recipients and an order of magnitude higher abundance in NFD-fed recipients, showing that the diet consumed by FMT recipients plays a role in xenobiotic colonization.

Helicobacter, mostly Helicobacter typhlonius MU96-1 (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 7A), prevailed among comparisons, reflecting its vulnerability to diet, exercise and even FMT. The co-modulation of Akkermansia muciniphila and H. typhlonius in intestinal tumor growth has recently been reported43. Although a prevalent intestinal colonizer in mice44, the role of H. typhlonius in the human gut and metabolism is still elusive. The overabundance of Odoribacter in exercised mice, in comparison to non-exercised mice (i.e., H-vs-HE and N-vs-NE), highlights the intimate association of Odoribacter with exercise. In addition, all FMT recipients (from exercised donors) exhibited significant increase in Odoribacter in comparison with controls (i.e., H-vs-H_FHE, H-vs-H_FNE and N-vs-N_FNE), indicating that the increase in Odoribacter is induced by FMT regardless of type of diet. As Odoribacter is a known producer of short chain fatty acids, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate45,46, increased Odoribacter may partly contribute to decreased inflammation, as evidenced by the diminished gene expressions of inflammatory cytokines in mice that were exercised or received FMT from exercised donors. The closest matches for Odoribacter OTUs were Odoribacter sp. strain Marseille-P2698 and Odoribacter splanchnicus strain DJF_B089 (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 7B), both of which have scarcely been investigated in the context of weight control and obesity.

AF12, of the family Rikenellaceae, showed constant overabundance in N, HE, H_FHE and H_FNE groups, when compared with H group, implying a role in weight control. Searching against the Rikenellaceae 16S rRNA gene sequences from NCBI, 62.6% of AF12 OTUs expectedly matched uncultured Rikenellaceae and 28.5% the genus Alistipes (Supplementary file: Supplementary Fig. 7C). Alistipes has been shown to be more abundant in healthy subjects than in HIV patients47, with reduced prevalence in diabetic patients after treatment48. Notably, a recent study of a 52-week weight-loss program revealed that a higher baseline proportion of Alistipes correlates with better weight loss and maintenance49. Similar to Odoribacter, Rikenellaceae bacteria are capable of producing butyrate46. These observations underlie the beneficial role of AF12.

On functional enrichment analysis, genes associated with electron transport chain (in oxidative phosphorylation) and glycolysis were enriched in HE mice when compared with H mice. Although the mechanism explaining how exercise selects (or alters) gut microbiota remains unclear, our results imply that exercise could establish a microbial community with proficiency in energy production via glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, which may contribute to some of the transmissible benefits (e.g., higher carbohydrate catabolism rate as reflected by reduced fat mass and food efficacy) from exercised FMT donors.

There are some limitations to the present study. First, fecal samples contained biological components in addition to bacteria, such as phages, fungi and metabolites, which might account for some of the transmissible benefits via FMT. The application of metagenomics to this study allowed for the dissection of the contribution of each fecal component to the beneficial effect and the potential involvement of bacteria was revealed. Second, to maximize the success rate of transplantation, daily FMT (5 days a week) was performed, which may not be feasible in clinical practice, although this schedule has been utilized in recent clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease50. A standard protocol for workable FMT frequency with guaranteed successful transplantation warrants further investigation. Third, our study was entirely based on murine models and extrapolation to humans must be performed with caution, although the proof of concept approach warrants appropriate human studies. Fourth, the running velocity, 18 m/min, represents the critical speed for the C57BL/6J mouse51, which is the maximum velocity a muscle group can maintain without exhaustion52. Therefore, the exercise regimen in our experimental setting (i.e., running at critical speed for 30 mins per day, 5 days per week) is very likely challenging for the ordinary human population. A systematic evaluation of exercise types, intensity, duration and practicality would help standardize the criteria for selecting desirable and effective FMT donors. Lastly, as the identified Helicobacter, Odoribacter and AF12 species are either recalcitrant to cultivation (strictly anaerobic) or without available isolates, we could not explore these further. However, the results are encouraging and merit further investigation.

The present study demonstrates for the first time that FMT from donors with normal diet and exercise confers metabolic benefits to HFD-fed recipients. Although diet played a more important role in shaping the gut microbiota in our study compared to exercise, the combined effect of healthy diet and exercise may constitute to an ideal gut microbiota for facilitating weight control. In conclusion, although this study is based on murine model and clinical effects in human trials remain to be verified, our findings provide proof of concept that obesity in a mammalian host can respond to FMT from donors with balanced diet, regular exercise or, even better, a combination of both.

Methods

Study design

In this study, mice were divided into seven groups (n = 47), including H (high fat diet, n = 6), HE (H with exercise, n = 7), N (normal fat diet, n = 7), NE (N with exercise, n = 6), H_FHE (H receiving FMT from HE, n = 7), H_FNE (H receiving FMT from NE, n = 7) and N_FNE (N receiving FMT from NE, n = 7). H represents the diet-induced obesity group independent from external treatment (e.g., exercise or FMT). N represents the treatment-naïve group with normal fat diet. Comparisons were performed for each group versus H to monitor the differential outcomes of metabolic and inflammatory profiles and gut microbiota under given treatments. Mice were randomly assigned to each group except for those in the exercised groups identified during 2-week assimilation training. Details of study design are shown in Fig. 1. Animal management, exercise regimen and FMT protocol are described below.

Animal model

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (La-1031216 and La-1041342) and performed in accordance with institutional guidelines. Male C57BL/6JNarl mice (n = 49), aged five weeks, were received from the National Laboratory Animal Center (Taipei, Taiwan). These mice were initially group housed in 7 cages (7 mice per cage) with free access to water and food. The mice in 4 cages were provided high fat diet (HFD; composition 60 kcal% fat, 20 kcal% carbohydrates, 20 kcal% protein; 5.24 kcal/g total energy content; Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and the mice in 3 cages were provided normal fat diet (NFD; composition 11 kcal% fat, 63 kcal% carbohydrates, 26 kcal% protein; 3.25 kcal/g total energy content; Fwusow Industry, Taichung, Taiwan). The housing conditions included constant temperature of 22 ± 1 °C and regular 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on 8 PM to 8 AM).

After a one-week acclimation period, all mice underwent assimilation training for 2 weeks to identify those competent to be enrolled in the exercised groups. Assimilation training was carried out individually for 39 minutes every Monday and Tuesday on a motorized treadmill outside the cage, starting with a 5-minute warm-up at 7 m/min that was followed by acceleration at 3 m/min every minute to a maximum speed of 18 m/min. After 2-week assimilation training, the mice were reallocated into 7 groups (H, HE, H_FHE, H_FNE, N, NE and N_FNE). Fourteen mice adaptable to treadmill running were assigned to exercised groups (7 in HE and 7 in NE) and underwent formal exercise regimen (18 m/min, 30 min/day, 5 days/week)53 following the same warm-up program as during assimilation training for 16 weeks. During exercise sessions, HE and NE mice were pulled from their respective cages and exercised on a motorized 5-lane treadmill at zero-percent incline. The chosen exercise paradigm aimed to create a high impact training model for C57BL/6J mice51,54. Forty-nine mice were initially enrolled in the experiment. Two were removed from downstream analysis, of which one in the H group was recalcitrant to HFD (increased 8 g by the end of experiment) and one in the NE group died during exercise at week 15.

Fecal sample collection and FMT

For comparative purposes, mice feces were collected twice for 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene amplicon sequencing, once at the beginning of week 12 (i.e., before FMT) and once at the end of week 24 (i.e., after FMT). About 100 mg of feces from each mouse were stored in 1 mL InhibitEX Buffer (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) at −80 °C for 1 week or less until DNA extraction.

After four weeks of formal exercise regimen (i.e., at week 12), feces from exercised mice were collected fresh for daily FMT, which was conducted under sterile conditions under laminar flow hood. Feces from exercised mice were pooled by cage, and 100 mg (about 5–6 fecal pellets) were re-suspended in 1 mL sterile saline. The solution was vigorously mixed for 10 seconds before centrifugation at 800 × g for 3 min. The supernatant (about 500–600 μL) was collected and administered by oral gavage within 10 min to minimize changes in microbial contents55.

Among the sedentary mice, 14 HFD-fed and 7 NFD-fed mice were randomly designated as FMT recipients (7 H_FHE, 7 H_FNE and 7 N_FNE) (Fig. 1). According to the established microbial depletion and recolonization protocol56,57,58,59, a combination of ciprofloxacin (0.2 g/L) and metronidazole (1 g/L) was added to the drinking water of FMT recipients for two days (i.e., the weekend of week 11) before FMT, to ensure that the outcomes are compatible with clinical guidelines for FMT in humans27. Ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole was chosen because it is one of the first-line antibiotic regimens recommended for the treatment of abdominal infections in adults60. Non-FMT recipients did not receive any antibiotics. Antibiotics were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA). From week 12, FMT was conducted each weekday, with each recipient administered 100 μL fecal supernatant by oral gavage until week 24.

Metabolic marker profiles of mice

For each mouse, body weight was measured weekly and intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was conducted monthly. For IPGTT, mice received intraperitoneal injection of 20% glucose with normal saline (2 g glucose/kg body mass) after 16-hour fast, and blood glucose levels at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes were measured using GM700 (BIONIME, Taichung, Taiwan).

Food consumption per group was recorded weekly, to monitor their feeding behavior throughout the FMT experimental period. Food efficacy was estimated for each group as grams of body weight gain per 100 g food consumed.

At the end of the experimental period, mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation after overnight fast. The chest was opened and blood was drawn from the left ventricle apex of heart. Serum was obtained by low-speed centrifugation (3000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C), then stored at −80 °C and delivered to the National Laboratory Animal Center within one week for measurement of fasting blood glucose, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol determinations using a Hitachi 7080 automatic chemistry analyzer (Hitachi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Intra-abdominal fat and epididymal fat were manually separated and collectively weighed as fat weight.

qPCRs of inflammatory cytokines in mice

Chronic inflammation in lipid is associated with HFD-induced obesity61. To quantitatively compare inflammation status of mice, the gene expression of related inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (Tnf), interleukin 1 alpha (Il1a) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparg)62,63, were measured in liver by quantitative polymerase chain reactions (qPCRs).

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissues and kept in TriPure isolation reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). Of the total RNA, 1 μg was treated with 10 units of RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA) and purified with phenol-chloroform. The purified RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using Advantage RT-for-PCR Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). FastStart Universal Probe Master and Universal Probe Library probes (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) were used in qPCRs. For each inflammatory cytokine gene (i.e., Tnf, Il1a and Pparg), qPCRs were performed in triplicate for each of the 47 cDNA pools along with a no template control in parallel. The primers and probes are listed in Supplementary Table 8 (Supplementary file). The qPCR cycling conditions were: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 sec, with a final extension at 60 °C for 1 min using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Relative gene expression was quantified by the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method, employing 18S rRNA gene (Rn18s) as internal control for normalization.

Statistical analysis of mice metabolic parameters and gene expression data

Differences in body weights among groups were evaluated by two-way ANOVA. For the remaining metabolic parameters and gene expression data (including fat weight, fasting blood glucose, IPGTT, Tnf expression, Il1a expression, Pparg expression, ALT and LDL), to avoid potential bias from sporadic outliers on statistical tests (e.g., one Tnf expression was higher than average by 99 folds), the 5% truncated mean (data within 5–95% quantile) was applied. The truncated mean is a robust estimator of the arithmetic mean because it is more resistant to outliers while providing a reasonable estimate of the central tendency of data64. The 50% truncated mean is equivalent to the median, and therefore the truncated mean is often regarded as a compromise between the arithmetic mean and median. With H the diet-induced obesity group, Student’s t-test was used to assess the respective difference in the means of other groups versus H, to understand the outcomes of external treatments designed to deal with obesity.

Histological examination

HFD is associated with fatty liver in mouse and humans29,30. Therefore, mice liver and fat pad tissues were subjected to histological examination to confirm the effectiveness of HFD in terms of adipose accumulation. After euthanasia, mice livers and fat pad tissues were collected in 10% formaldehyde for histological examination by Bestjet Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Taipei, Taiwan). Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was applied to both tissue types and oil red O staining was applied to fat pad tissues. After staining, tissues were examined under light microscope at 200× magnification.

Fecal DNA extraction

Fecal DNA was extracted using QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen). DNA quality and quantity were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). DNA was stored at −80 °C until 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (at least 500 ng per sample).

16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and analysis

The hypervariable regions V3–V4 of bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR using bar-coded universal primers 341F (F, forward primer; 5′-CCTACgggNggCWgCAg-3′) and 805R (R, reverse primer; 5′-gACTACHVgggTATCTAATCC-3′). Library construction and sequencing of amplicon DNA samples were done by Genomics BioScience (Taipei, Taiwan). A pair-end library (insert size of 465 bp for each sample) was constructed using MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, Wilmington, DE, USA) and high-throughput sequencing was performed on Illumina MiSeq2000 platform (Illumina).

Bioinformatics analysis of 16S rRNA gene amplicons was performed by Germark Biotechnology (Taichung, Taiwan). Briefly, USEARCH (v7.0.1090) was used to merge pair-end reads on a per-sample basis, setting 8 bp as the minimum overlap of read pair. Mothur (v1.34.3) was used for quality-filtering to retain reads with: (1) a length of 400–550 bp, (2) a minimum average quality score of 27, (3) no ambiguous base and (4) homopolymers not exceeding 8 bp. Chimera detection was performed by UCHIME65 as implemented in USEARCH using reference mode and 3% minimum divergence. Quality-filtered and non-chimeric reads were further analyzed according to UPARSE pipeline66 to generate OTUs per sample (97% identity level). OTU representative sequences were searched against the Greengenes 13_5 database using USEARCH global alignment to identify the corresponding taxonomy of the best hit. Any OTU without a hit or with only a weak hit (i.e., the average of % sequence identity and % alignment coverage <93) was excluded from following analyses.

Statistical and bioinformatics analyses of microbiota

All statistical analyses were performed using R (https://www.r-project.org/), unless otherwise specified. PCoA was conducted with R package phyloseq based on OTU-level Bray–Curtis distance measure. Between-group inertia percentage was evaluated using R package ade4 with Monte-Carlo test (with 1000 permutations) to determine the p value of PCoA results. Two-way PERMANOVA was performed by R package vegan using OTU-level Bray–Curtis distance matrix with 999 permutations. Shannon diversity index was estimated at OTU level by R package phyloseq and tested for associations with sampling time (before and after FMT), diet, exercise and FMT status by linear modeling, in which the data of H_FHE and H_FNE before FMT were categorized into H group and that of N_FNE before FMT into N group. To identify genera differentially enriched in the between-group comparisons, LEfSe was applied with α = 0.05 (Kruskal–Wallis and Wilcoxon tests) and effect size threshold of two on LDA using the stand-alone implementation (https://bitbucket.org/nsegata/lefse). Enriched genera identified by LEfSe were further filtered by a group-mean difference in relative abundance larger than 10−5 to exclude genera absent in one group and minutely abundant in another. To deliver a more intuitive perception of contrasting abundance, LEfSe results were visualized by plotting the log-2 ratio of average relative abundance between groups rather than the LDA score. The abundance profile of functional genes (i.e., COGs) of each microbial community was predicted using PICRUSt (v1.0.0). To identify functional genes with differential abundances, enrichment analysis was performed by a two-group comparison for medians using two-tailed Wilcoxon test with a Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction to adjust q-values for multiple testing. The R code for all statistical analyses is available in Supplementary dataset, and was created by the R package knitr67.

Data Availability

Sequence files and metadata of all samples have been deposited in National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRP102269, affiliated with BioProject PRJNA379878. The metadata, OTU and taxonomy tables, and COGs and annotation tables (predicted by PICRUSt) have also been deposited in Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5513548), and serve as input data for the R code in Supplementary dataset used to perform all statistical analyses in this manuscript.

References

Turnbaugh, P. J. et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444, 1027–1031, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05414 (2006).

Tremaroli, V. & Backhed, F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 489, 242–249, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11552 (2012).

Turnbaugh, P. J., Backhed, F., Fulton, L. & Gordon, J. I. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 3, 213–223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015 (2008).

Denou, E., Marcinko, K., Surette, M. G., Steinberg, G. R. & Schertzer, J. D. High-intensity exercise training increases the diversity and metabolic capacity of the mouse distal gut microbiota during diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 310, E982–993, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00537.2015 (2016).

Barton, W. et al. The microbiome of professional athletes differs from that of more sedentary subjects in composition and particularly at the functional metabolic level. Gut. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313627 (2017).

Ley, R. E. et al. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 11070–11075, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0504978102 (2005).

Zhang, X. et al. Modulation of gut microbiota by berberine and metformin during the treatment of high-fat diet-induced obesity in rats. Sci Rep 5, 14405, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14405 (2015).

Fei, N. & Zhao, L. An opportunistic pathogen isolated from the gut of an obese human causes obesity in germfree mice. ISME J 7, 880–884, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.153 (2013).

Cani, P. D. et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57, 1470–1481, https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-1403 (2008).

Lam, Y. Y. et al. Increased gut permeability and microbiota change associate with mesenteric fat inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in diet-induced obese mice. PLoS One 7, e34233, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034233 (2012).

Cani, P. D. et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 56, 1761–1772, https://doi.org/10.2337/db06-1491 (2007).

Pendyala, S., Walker, J. M. & Holt, P. R. A high-fat diet is associated with endotoxemia that originates from the gut. Gastroenterology 142, 1100–1101.e1102, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.034 (2012).

Amar, J. et al. Energy intake is associated with endotoxemia in apparently healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr 87, 1219–1223, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1219 (2008).

Campbell, S. C. et al. The effect of diet and exercise on intestinal integrity and microbial diversity in mice. PLoS One 11, e0150502, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150502 (2016).

Martins, C., Morgan, L. M., Bloom, S. R. & Robertson, M. D. Effects of exercise on gut peptides, energy intake and appetite. J Endocrinol 193, 251–258, https://doi.org/10.1677/JOE-06-0030 (2007).

Broom, D. R., Stensel, D. J., Bishop, N. C., Burns, S. F. & Miyashita, M. Exercise-induced suppression of acylated ghrelin in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 102, 2165–2171, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00759.2006 (2007).

Matsumoto, M. et al. Voluntary running exercise alters microbiota composition and increases n-butyrate concentration in the rat cecum. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72, 572–576, https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.70474 (2008).

Segain, J. P. et al. Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFkappaB inhibition: implications for Crohn’s disease. Gut 47, 397–403 (2000).

Gao, Z. et al. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes 58, 1509–1517, https://doi.org/10.2337/db08-1637 (2009).

Furusawa, Y. et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 504, 446–450, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12721 (2013).

Cryan, J. F. & Dinan, T. G. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 701–712, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3346 (2012).

Oettle, G. J. Effect of moderate exercise on bowel habit. Gut 32, 941–944 (1991).

Vandeputte, D. et al. Stool consistency is strongly associated with gut microbiota richness and composition, enterotypes and bacterial growth rates. Gut 65, 57–62 (2016).

Falony, G. et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science 352, 560–564, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad3503 (2016).

Dokladny, K., Zuhl, M. N. & Moseley, P. L. Intestinal epithelial barrier function and tight junction proteins with heat and exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 120, 692–701, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00536.2015 (2016).

Lira, F. S. et al. Endotoxin levels correlate positively with a sedentary lifestyle and negatively with highly trained subjects. Lipids Health Dis 9, 82, https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-9-82 (2010).

Cammarota, G. et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 66, 569–580, https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313017 (2017).

Cox, L. M. & Blaser, M. J. Antibiotics in early life and obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11, 182–190, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.210 (2015).

Cohen, J. C., Horton, J. D. & Hobbs, H. H. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science 332, 1519–1523, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204265 (2011).

Zivkovic, A. M., German, J. B. & Sanyal, A. J. Comparative review of diets for the metabolic syndrome: implications for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Clin Nutr 86, 285–300 (2007).

Musso, G., Gambino, R. & Cassader, M. Interactions between gut microbiota and host metabolism predisposing to obesity and diabetes. Annu Rev Med 62, 361–380, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-012510-175505 (2011).

Chi, W. et al. Bacterial peptidoglycan stimulates adipocyte lipolysis via NOD1. PLoS One 9, e97675, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097675 (2014).

Clarke, T. B. et al. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat Med 16, 228–231, https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2087 (2010).

Schertzer, J. D. et al. NOD1 activators link innate immunity to insulin resistance. Diabetes 60, 2206–2215, https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-0004 (2011).

Cavallari, J. F. et al. Muramyl Dipeptide-Based Postbiotics Mitigate Obesity-Induced Insulin Resistance via IRF4. Cell Metab 25, 1063–1074 e1063, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.03.021 (2017).

Hedl, M., Li, J., Cho, J. H. & Abraham, C. Chronic stimulation of Nod2 mediates tolerance to bacterial products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 19440–19445, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706097104 (2007).

Denou, E. et al. Defective NOD2 peptidoglycan sensing promotes diet-induced inflammation, dysbiosis, and insulin resistance. EMBO Mol Med 7, 259–274, https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201404169 (2015).

Jin, S. A. et al. The Curves Exercise Suppresses Endotoxemia in Korean Women with Obesity. J Korean Med Sci 32, 272–277, https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.2.272 (2017).

Allen, J. M. et al. Exercise training-induced modification of the gut microbiota persists after microbiota colonization and attenuates the response to chemically-induced colitis in gnotobiotic mice. Gut Microbes, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2017.1372077 (2017).

Queipo-Ortuno, M. I. et al. Gut microbiota composition in male rat models under different nutritional status and physical activity and its association with serum leptin and ghrelin levels. PLoS One 8, e65465, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065465 (2013).

Welly, R. J. et al. Comparison of diet versus exercise on metabolic function and gut microbiota in obese Rats. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48, 1688–1698, https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000964 (2016).

Guo, X. et al. High fat diet alters gut microbiota and the expression of paneth cell-antimicrobial peptides preceding changes of circulating inflammatory cytokines. Mediators Inflamm 2017, 9474896, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9474896 (2017).

Dingemanse, C. et al. Akkermansia muciniphila and Helicobacter typhlonius modulate intestinal tumor development in mice. Carcinogenesis 36, 1388–1396, https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgv120 (2015).

Wasimuddin et al. High prevalence and species diversity of Helicobacter spp. detected in wild house mice. Appl Environ Microbiol 78, 8158–8160, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01989-12 (2012).

Goker, M. et al. Complete genome sequence of Odoribacter splanchnicus type strain (1651/6). Stand Genomic Sci 4, 200–209, https://doi.org/10.4056/sigs.1714269 (2011).

Vital, M., Howe, A. C. & Tiedje, J. M. Revealing the bacterial butyrate synthesis pathways by analyzing (meta)genomic data. MBio 5, e00889, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00889-14 (2014).

McHardy, I. H. et al. HIV infection is associated with compositional and functional shifts in the rectal mucosal microbiota. Microbiome 1, 26, https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-2618-1-26 (2013).

Xu, J. et al. Structural modulation of gut microbiota during alleviation of type 2 diabetes with a Chinese herbal formula. ISME J 9, 552–562, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.177 (2015).

Louis, S., Tappu, R. M., Damms-Machado, A., Huson, D. H. & Bischoff, S. C. Characterization of the gut microbial community of obese patients following a weight-loss intervention using whole metagenome shotgun sequencing. PLoS One 11, e0149564, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149564 (2016).

Paramsothy, S. et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 389, 1218–1228, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30182-4 (2017).

Billat, V. L., Mouisel, E., Roblot, N. & Melki, J. Inter- and intrastrain variation in mouse critical running speed. J Appl Physiol (1985) 98, 1258–1263, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00991.2004 (2005).

Moritani, T., Nagata, A., Devries, H. A. & Muro, M. Critical power as a measure of physical work capacity and anaerobic threshold. Ergonomics 24, 339–350, https://doi.org/10.1080/00140138108924856 (1981).

Basterfield, L. & Mathers, J. C. Intestinal tumours, colonic butyrate and sleep in exercised Min mice. Br J Nutr 104, 355–363, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510000528 (2010).

Kennard, J. A. & Woodruff-Pak, D. S. A comparison of low- and high-impact forced exercise: effects of training paradigm on learning and memory. Physiol Behav 106, 423–427, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.02.023 (2012).

Chang, C. J. et al. Ganoderma lucidum reduces obesity in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota. Nat Commun 6, 7489, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8489 (2015).

Reikvam, D. H. et al. Depletion of murine intestinal microbiota: effects on gut mucosa and epithelial gene expression. PLoS One 6, e17996, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017996 (2011).

McCafferty, J. et al. Stochastic changes over time and not founder effects drive cage effects in microbial community assembly in a mouse model. ISME J 7, 2116–2125, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.106 (2013).

Bruce-Keller, A. J. et al. Obese-type gut microbiota induce neurobehavioral changes in the absence of obesity. Biol Psychiatry 77, 607–615, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.012 (2015).

Suez, J. et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 514, 181–186, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13793 (2014).

Solomkin, J. S. et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 50, 133–164, https://doi.org/10.1086/649554 (2010).

Xu, H. et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112, 1821–1830, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI19451 (2003).

Yimin et al. A novel murine model for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis developed by combination of a high-fat diet and oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Lab Invest 92, 265–281, https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2011.159 (2012).

Daynes, R. A. & Jones, D. C. Emerging roles of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2, 748–759, https://doi.org/10.1038/nri912 (2002).

Huber, P. J. & Ronchetti, E. M. Robust Statistics. (Wiley, 2009).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods 10, 996–998, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2604 (2013).

Xie, Y. knitr: a comprehensive tool for reproducible research in R. Implement Reprod Res 1, 20 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 105-2314-B-075A-013), Taiwan. The authors would like to thank Germark Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Taichung, Taiwan) for assistance with the microbiome bioinformatics analysis. E.M.E.-O. is supported by funding from the Australian Federal Government through the St George and Sutherland Medical Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-Y.W., E.M.E.-O. and Z.-L.L. contributed to the study concept and design. Z.-L.L., J.-Y.L. and H.J.H. contributed to data acquisition. C.-Y.W., H.J.H. and C.-H.T. performed statistical analyses. C.-H.T. and H.J.H. compiled the R code for all statistical analyses. Z.-L.L., C.-Y.W. and C.-H.T. contributed to data interpretation. C.-Y.W., E.M.E.-O., C.-H.T., Z.-L.L. and C.K.-Y.C. drafted the manuscript. C.-H.T, Y.-J.C., Y.-C.H. and J.-T.L. performed critical revision of the manuscript and contributed important intellectual content. C.-Y.W. and Z.-L.L. searched for funding sources. F.-C.C. provided technical and material support for animal experiment. C.-Y.W. supervised the entire study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, ZL., Tseng, CH., Ho, H.J. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation confers beneficial metabolic effects of diet and exercise on diet-induced obese mice. Sci Rep 8, 15625 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33893-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33893-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Impact of the gut microbiota and associated metabolites on cardiometabolic traits, chronic diseases and human longevity: a Mendelian randomization study

Journal of Translational Medicine (2023)

-

Chicken cecal microbiota reduces abdominal fat deposition by regulating fat metabolism

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2023)

-

Roles of the gut microbiome in weight management

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2023)

-

Health improvements of type 2 diabetic patients through diet and diet plus fecal microbiota transplantation

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Host gut resistome in Gulf War chronic multisymptom illness correlates with persistent inflammation

Communications Biology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.