Abstract

We aimed to assess the impact of timing of surgery in elderly patients with acute hip fracture on morbidity and mortality. We systematically searched MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, Embase, PubMed, and trial registries from 01/1997 to 05/2017, as well as reference lists of relevant reviews, archives of orthopaedic conferences, and contacted experts. Eligible studies had to be randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or prospective cohort studies, including patients 60 years or older with acute hip fracture. Two authors independently assessed study eligibility, abstracted data, and critically appraised study quality. We conducted meta-analyses using the generic inverse variance model. We included 28 prospective observational studies reporting data of 31,242 patients. Patients operated on within 48 hours had a 20% lower risk of dying within 12 months (risk ratio (RR) 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66–0.97). No statistical significant different mortality risk was observed when comparing patients operated on within or after 24 hours (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67–1.01). Adjusted data demonstrated fewer complications (8% vs. 17%) in patients who had early surgery, and increasing risk for pressure ulcers with increased time of delay in another study. Early hip surgery within 48 hours was associated with lower mortality risk and fewer perioperative complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hip fractures in elderly populations are a major public health concern in Europe and the United States (US)1,2,3. The annual incidence of hip fractures rises with age. In the US, it ranges between 0.2% in women aged 60 to 64 years to 2.5% in women aged 85 years or older4. In Europe, the annual hip fracture incidence for elderly women aged 60 years or older ranges between 0.5% to 1.6% per year5,6,7. The risk for men is about half of that for women8.

Hip fractures in elderly patients are serious injuries that can lead to immobility and permanent dependence, negatively impacting patients’ quality of life and resulting in a financial burden for health systems and societies7,8,9,10. Hip fractures can also lead to death. Mortality rates among the elderly following hip fractures range between 14% to 36% within 1 year of the injury11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. During the first three months after hip fracture, elderly patients have a 5- to 8-fold increased risk of dying20. The increased mortality risk persists up to ten years20. Because of a predicted increase in life expectancy in western countries over the next decades21,22,23, hip fractures and their consequences will have an even larger impact on health systems and societies in the future.

Factors that influence prognosis of elderly patients after hip fracture are age, gender, comorbidities, anticoagulation therapy, and general physical health status at the time of injury24. Furthermore, timing of surgery is thought to play an important role regarding survival. Although international clinical practice guidelines recommend surgical treatment of acute hip fracture within 24 to 48 hours after admission25,26,27, these recommendations are still discussed controversially28,29,30. Some researchers argue that early surgery can lead to an increased risk of perioperative complications, including pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis, bleeding, pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infections, and decubital ulcerations because clinicians do not have enough time to optimise patients’ medical conditions preoperatively29,30,31.

The most recent systematic review on this topic was published in 201032. Since then, many well-conducted studies have been published. To provide a comprehensive overview, it is necessary to systematically review the currently available evidence on the impact of timing of surgery in elderly patients with acute hip fracture. In contrast to former reviews that focused exclusively on mortality, we additionally aimed to assess other patient-relevant outcomes, such as perioperative complications, functional capacity, and quality of life. We also explored whether timing of surgery has different effects in different subgroups, e.g., in patients on anticoagulation treatment or patients with poor physical status.

Our systematic review aimed to answer the following questions:

-

(1)

In patients aged 60 years or older with an acute hip fracture, what is the impact of timing of surgery on beneficial and harmful outcomes such as mortality, functional capacity, quality of life, and perioperative complications?

-

(2)

Do beneficial or harmful treatment effects of timing of surgery vary by subgroups based on patient characteristics (age, sex), physical status (e.g., ASA Physical Status System), and common medical treatments (e.g., anticoagulation treatment)?

Methods

To answer our research questions, we conducted a systematic review that has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number: CRD4201705821633. The study protocol has been published previously34. We will summarise the most important methodological steps in the sections below.

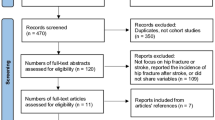

Search Strategy and Criteria

An experienced information specialist searched MEDLINE (Ovid), PubMed (non-MEDLINE content), Embase.com, the Cochrane Library (Wiley), for the period of January 1997 to May 2017, using keywords and medical subject headings for hip fracture surgery, adult patients, and timing factors. To ensure finding all relevant studies on this topic a broad range of synonyms where used for the search (see Appendix 1 for the search strategy). In addition, we searched the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov, as well as reference lists of relevant publications, websites and conference proceedings of orthopaedic and traumatological societies (see Appendix 2).

Inclusion and Exclusion

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were predetermined in the published protocol35. Eligible study designs were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomised controlled trials, and prospective controlled cohort studies. The populations of interest were adults aged 60 years or older undergoing surgery for acute intra- and extracapsular hip fracture. We also included studies where only a small proportion (<5%) of patients were younger than 60 years. Studies were included only if they compared early and delayed surgery for hip fractures. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes of interest were perioperative complications, functional capacity, and quality of life. Detailed eligibility criteria are presented in Table 1.

Assessment of Study Quality and Certainty of Evidence

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa-Scale (NOS) to judge the risk of bias in included cohort studies36. Two authors independently assessed the risk of selection bias, comparability of groups, adequacy of outcome measurement, and reporting. We resolved disagreements by consensus or involvement of a third review author.

In addition, we assessed the certainty of evidence (CoE) across studies for important outcomes following recommendations of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group37. Experts in the field of orthopaedics and traumatology ranked outcomes regarding clinical and patients’ relevance in a modified two-staged Delphi process. They agreed on mortality, quality of life, perioperative complications, and function/mobility as the most important outcomes. For these outcomes, we graded the certainty of evidence and classified it as “high,” “moderate,” “low,” or “very low.” High certainty means we are very confident that the true effect is close to the effect estimate. On the contrary, if the certainty is very low, we assume that the true effect is likely to be significantly different from the effect estimate37.

Data Collection and Abstraction

Two review authors independently reviewed abstracts and full-text articles in two consecutive steps. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third author. Two team members independently extracted relevant information on study design, methods, patient characteristics, intervention, control, and outcomes from included studies. In case information about relevant outcomes or study characteristics was missing or unclear, we contacted study authors.

Meta-analysis Methodology

We used the generic inverse variance method to combine effects of individual observational studies that were adjusted for potential confounders and were rated as low or moderate risk of bias in meta-analyses. We pooled data only if at least three studies used comparable cut-offs for “early” and “delayed” surgery and reported the same outcome. In case the studies reported hazard ratios (HR) or odds ratios (OR), we converted them into risk ratio (RR) using the following formulas for HR: RR = 1 − e (HR* ln (1 − P0))/P032, and for OR: RR = OR/((1 − P0) + (P0 * OR))38; P0 means the event rate in the control group. For one study39, we were not able to calculate P0 because no crude numbers of events were reported, so we used the mean P0 from the other included studies to convert OR into RR. We added observational studies with unadjusted results, irrespective of their risk of bias judgment to meta-analyses for sensitivity analyses.

To assess statistical heterogeneity in effects between studies, we calculated the chi-squared statistic and the I2 statistic (the proportion of variation in study estimates attributable to heterogeneity rather than due to chance)40,41. Due to the limited number of studies included in meta-analyses, no funnel plots could be used to assess publication bias. We used RevMan Version 5.342 for all statistical analyses.

For outcomes for which no meta-analyses were possible, we summarise data narratively. If several studies reported the same outcome but meta-analyses were not possible because of high clinical heterogeneity or because the study was rated high risk of bias, we graphically display results in forest plots without pooled summary estimates.

Because data were not sufficient to conduct subgroup analyses, we summarise these results narratively.

Results

Study characteristics

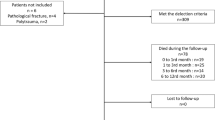

We included 28 prospective cohort studies13,29,31,39,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67 (published in 30 articles) reporting results on 31,242 patients (see Fig. 1, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart). We could not detect any eligible RCTs.

Of the 28 included studies, 15 had a low29,46,53,57,62,68 or moderate13,31,39,45,47,52,55,64,65,66 risk of bias, and 13 studies were rated high risk of bias43,44,48,49,50,51,54,56,58,59,60,61,63. Most studies used a cut-off time for surgical delay of 48 or 24 hours; other studies used (additional) cut-offs at 6 hours, 12 hours, 18 hours, 36 hours, and 72 hours. Table 2 presents study and patient characteristics of included studies.

Mortality

Overall, 25 studies reported on all-cause mortality: nine studies (14,863 patients) provided adjusted hazard ratios (HR) or odds ratios (OR) for mortality13,29,31,39,45,53,57,58,62, adjusting at least for age, sex, and patient’s health status; 16 studies43,44,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,59,60,61,64,65,66 (14,654 patients) reported unadjusted effect estimates on mortality.

Cut-off 48 hours

Based on a meta-analysis of adjusted data from four studies13,39,62,68 the absolute risk of dying within 12 months was 21% in patients who had surgery after 48 hours and 17% in patients who had surgery within 48 hours resulting in a 20% smaller long-term mortality risk in patients operated on within 48 hours (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66-0.97, 2,396 patients, see Fig. 2). We graded the CoE for this outcome as low. We also conducted sensitivity analyses by adding unadjusted data on mortality from the remaining studies to the meta-analysis, irrespective of their bias risk. Adding the non-adjusted data did not alter the results for long-term mortality (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.64-0.84, 8,903 patients)13,39,43,46,51,57,59,62,65,68 (see Fig. 2). No statistically significant differences were observed in two studies presenting adjusted data on short-term mortality (within 1 months) (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.59-1.35, 6,638 patients; RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.66-1.10, 218 patients; CoE: very low)39,53. In sensitivity analyses, including unadjusted data, surgery within 48 hours was associated with a statistical significant benefit on short-term mortality (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62-0.98, 9,371 patients)39,43,53,54,58 (see Appendix 3, Fig. 5).

Cut-off 24 hours

A meta-analysis of three trials29,62,65(2,853 patients) rendered an 18% lower risk of long-term mortality in patients operated on within 24 hours (within 12 months: RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67-1.01, CoE: low, absolute mortality risk early surgery: 17%, delayed: 14%) (see Fig. 2). When adding unadjusted data in sensitivity analyses, the difference between surgery within and after 24 hours was statistically significant (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.56-0.84, 7,069 patients)29,44,48,49,62,64,65,69 (see Fig. 2). No statistically significant differences were observed in two studies presenting adjusted data on short-term mortality (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.84-1.26, 6,638 patients; RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.49, 222 patients; CoE: very low)45,53, as well as in sensitivity analyses (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.85-1.29)31,45,47,53,54,61 (see Appendix 3, Fig. 7).

Figure 2 summarises results of meta-analyses on long-term mortality and corresponding sensitivity analyses.

Data were insufficient to conduct meta-analyses for other cut-offs (6, 12, 18, 36, 72 hours) of timing of surgery. However, to illustrate the results on mortality of all studies, we present forest plots for each cut-off in Appendix 3 (48 hours: see Fig. 5, 36 hours: see Fig. 6, 24 hours: see Fig. 7, 18 hours: see Fig. 8, 12 hours: see Figs 9, 6 hours: see Fig. 10, 72 hours: see Fig. 11).

Perioperative Complications

Two studies with low62 and medium52 risk of bias reported adjusted data on general perioperative complications or pressure ulcers, respectively. Mariconda et al. reported data on 568 patients and showed that surgery within 72 hours was associated with decreased odds of general complications such as pressure ulcers, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis/embolism, or stroke (absolute risk of complications: 17% vs. 8%; OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.31-0.85, see Fig. 3)52.

Six studies reported unadjusted data for perioperative complications29,48,54,55,58,64. Figure 3 presents unadjusted effect estimates of individual studies. While a cut-off of 6 hours did not show significantly different rates of complications, patients who had surgery within 24 or 48 hours suffered from complications less frequently than those with late surgery.

One study on 744 patients used three different cut-offs (24, 36, 48 hours) for “delayed surgery” and presented adjusted data for pressure ulcers. The odds of developing pressure ulcers increased with the time of delay (>24 hours: OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.21-3.96; >36 hours: OR 3.42, 95% CI 1.94-6.04; >48 hours: OR 4.34, 95% CI 2.34-8.04)62. In studies reporting unadjusted data the risk for developing pressure ulcers, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, or thromboembolic events was either smaller for patients who had early surgery or similar between both groups; it was not higher in any study for patients who had early surgery (see Fig. 4). CoE for perioperative complications was very low.

Quality of life

None of the included studies reported how timing of surgery affects the patients’ quality of life.

Functional capacity

Measuring of mobility and functional capacity was different among eight studies29,44,48,56,57,61,63,66 and data are summarised in Table 3. Patients who had early surgery had similar or slightly better functional capacity compared to those operated on later (CoE: very low).

Impact of timing of surgery in subgroups

Due to insufficient data, we were not able to conduct subgroup analyses to assess different effects of timing of surgery between age groups, sex, patients’ physical status, and anticoagulation. However, six studies assessed the effects of timing of surgery in different subgroups29,47,54,57,58,61. Below we present results narratively.

Age

In two studies, timing of surgery (before or after 24 hours) showed no significant difference in mortality rates in different age groups. Yonezawa et al. showed that there was no statistically significant difference in mortality in patients 85 years and older, whether they had surgery within 24 hours or later (early: 10/136; 7% vs. delayed: 5/117; 4%; p = 0.301), as well as in patients younger than 85 years (early: 5/134; 4% vs. delayed: 2/149; 1%; p = 0.363)61. Vidán et al. also reported that time to surgery and age showed no interaction (p = 0.500)58.

Sex

In male patients, early surgery (within 24 hours) was associated with higher mortality (6/40; 15% vs. 1/51; 2%; p = 0.040), in females it was not (9/230; 4% vs. 6/215; 3%; p = 0.512)61. However, event rates are very small, and the observed differences could be chance findings.

Physical status

Timing of surgery (before or after 24 hours) was associated with similar mortality rates in dependently (early: 6/173; 4% vs. delayed: 3/174; 2%; p = 0.494) and independently living patients (early: 9/96; 9% vs. delayed: 4/90; 4%; p = 0.188). Patients with comorbidities benefited more often from surgery within 24 hours (early: 3/196; 7% vs. delayed 5/200; 3%; p = 0.048). In medically fit patients without comorbidities no statistically significant difference between early and delayed was detected61. Again, the low number of events makes chance findings inevitable.

Another study divided patients into two groups, either fit or unfit for immediate surgery, depending on their physical status. In the group of patients considered fit for surgery, no statistically significant difference between early (within 24 hours) and delayed surgery was observed regarding 30-day mortality (85/982; 9% vs. 85/1166; 7%; p = 0.510)47. In the group of patients with acute medical comorbidities, there was no significant relationship between timing of the surgery and mortality at 30 days, 90 days, or one year (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.34-1.39; p = 0.290; HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.72-1.86; p = 0.540; HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.68-1.58; p = 0.880, respectively). A delay of more than one day from injury to presentation was associated with higher mortality in this group of patients (HR 2.1, 95% CI 1.01-4.2; p = 0.048)47.

Hapuarachchi et al. included 146 patients at the age of 90 or older54 and stratified patients according to the orthopaedic POSSUM (The Physiological and Operative Severity Score for enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity) score. Mortality was statistically significant higher in patients with POSSUM scores of ≥42 and delayed surgery (after 48 hours) as compared with early surgery (within 48 hours): early: 7% vs. delayed: 50%; p = 0.009. In patients with lower POSSUM scores no difference in mortality between early (within 48 hours) and delayed surgery was reported (POSSUM score 37-40: early: 8% vs. delayed: 11%, p = 0.500; POSSUM score ≤ 36: early: 24% vs. delayed: 50%, p = 0.310).

Pioli et al. hypothesised that timing of surgery is more important for frail elderly patients than for older people without functional impairment. Therefore, they divided patients into three groups according to their IADL (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) score. One-year mortality in group 1 (dependent) and group 2 (intermediate level) relatively increased by 14% and 21%, respectively, per day of surgical delay (HR 1.14; 95% CI 1.06-1.22, p < 0.001 and HR 1.21; 95% CI 1.09-1.34, p < 0.001), but not in group 3 (high independence; HR 1.05; 95% CI 0.79-1.41, p = 0.706)57.

In a prospective cohort study including 1,206 patients, those with abnormal clinical findings or the need for further preoperative evaluation were excluded to form a restricted cohort of medically fit patients. In this group, early surgery within 24 hours had no association with functional outcomes or mortality, but was associated with reduced major postoperative complications (p = 0.041)29.

Anticoagulation treatment

In most of the studies, anticoagulants were more common in the delayed group and frequently caused surgical delay13,39,48,51. However, we did not identify any study reporting on differences between early and delayed surgery in patients with and without anticoagulation treatment.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review critically assessing all relevant prospective studies on this topic since 2010. We identified 20 new studies that had not been considered in the previous reviews32,70,71. Our findings agree with previous systematic reviews. Simunovic et al. showed that early surgery (within 24 to 72 hours) can reduce the risk of all-cause mortality in patients aged 60 or older by 19% (risk ratio (RR) 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68–0.96)32. Early surgery was also associated with a reduction of pressure ulcers and postoperative pneumonia (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.34-0.69)32. Another systematic review including prospective and retrospective observational studies also demonstrated that a delay in surgery beyond 48 hours was associated with an increased 1-year-mortality and 30-day mortality risk (odds ratio (OR) 1.32, 95% CI 1.21-1.43; 30-day mortality: OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.29–1.54)70.

In contrast to other systematic reviews we looked at the effect of different cut-offs for “early” and “delayed” surgery separately and found that early surgery within 48 hours was associated with decreased long-term mortality in elderly patients after hip fractures. Single studies using other cut-offs (6, 12, 18, 24 or 36 hours) did not demonstrate significant differences in mortality between early and delayed surgery. However, these studies were probably underpowered and it is important to note that no study demonstrated a beneficial effect of delayed surgery on mortality.

Although findings of this review strengthen existing guidelines recommending surgery within 48 hours, in clinical practice, delay of surgery of hip fractures is quite common. In situations where patients need medical optimisation due to poor health status or long-term medication72, delays cannot be avoided. However, the reasons for delayed surgery are also often limited capacity of operating rooms and personnel, or weekend and holiday administration32,58,73,74. Cha et al. showed that hospital factors are accountable for three-fourths of the surgical delays74. In the interest of high quality care, organisational and structural improvements, such as better availability of operating rooms and staff, are necessary to enable early surgery. There is also general agreement that rapidly correctable comorbidities such as anaemia, hypovolemia, electrolyte imbalance, and correctable cardiac arrhythmias should not delay the operation27.

Only six of the included studies reported the effects of time to surgery in our predefined subgroups. In healthy, independent patients, delayed surgery was not as problematic as in patients with comorbidities. In most of these studies, the event rate was very small. Hence, the results could be chance findings. Moreover, the studies presented only unadjusted data. It should be emphasised that conclusions based on this data must be drawn carefully. Nevertheless, if availability of staff and operation room is limited, comorbid patients could be prioritised and have early surgery, presupposing that they do not have clear contraindications for surgery.

Our study has some limitations. We graded the certainty of evidence for all outcomes low or very low, which means that our confidence in the findings is limited. One reason for the low certainty of evidence is that we only identified prospective cohort studies but no RCTs. Results of observational studies must be interpreted with caution since confounding could distort the findings. It is possible that non-organisational reasons for delay of surgery such as need for medical optimisation also increased the risk of dying, independently, or in addition to timing of surgery. To minimise the distortion through confounding we included for our main analysis only data from adjusted analyses where at least the most important confounders such as age, gender, ASA score, fracture type and comorbidities had been considered. However, due to lack of randomisation, confounding cannot be completely eliminated.

The studies identified used different cut-offs to define early and delayed surgery. We combined only data from studies using very similar cut-offs. This allowed us to include only a small number of the included studies into meta-analyses. However, presenting the evidence for different cut-offs separately is relevant to inform clinical practice about the optimal timing of surgery.

No study conducted subgroup analysis with tests for interaction. However, some analysed the effect of timing of surgery in separate strata, allowing us to draw some conclusions about different effects in subgroups. Moreover, often the number of events was very small, making chance findings very likely. The results on subgroups therefore have to be interpreted with caution.

Despite our comprehensive search, it is possible that not all studies conducted on this topic have been detected (e.g., studies published in languages other than English or German). Publication bias cannot be ruled out, and we were not able to assess potential publication bias with a funnel plot. However, we contacted experts in the field, searched trial registries, and ultimately found 20 new studies that have not been included in former systematic reviews.

To overcome the limitation of observational studies, RCTs on this topic are needed. Although experts often argue, that this is unethical and not possible to implement, a RCT on timing of surgery in hip fracture patients is on the way. The HIP-ATTACK trial (HIP fracture Accelerated surgical TreaTment And Care tracK) will compare the effect of accelerated surgery and standard surgical care on perioperative complications and mortality75. A total of 1,200 patients older than 45 with low-energy hip fracture will be included in the study. The results of this trial will inform clinical practice and for the first time control adequately for known and unknown confounders.

Conclusion

In elderly patients sustaining hip fracture, early surgery is associated with reduced mortality and perioperative complications. Patients operated on within 48 hours had a 20% lower 1-year mortality.

However, timing of surgery for patients with hip fractures remains a challenge, as it requires multidisciplinary coordination between different occupational groups and the availability of appropriate surgical capacity with competent staff and proper equipment. No study demonstrated a survival benefit with delayed surgery. Future studies should investigate the effect of early surgery in subgroups of patients (e.g. patients with greater co-morbidities or anticoagulation treatment) and include data on patient-relevant outcomes, such as quality of life measurements. Furthermore, randomised controlled trials are needed to rule out potential confounding.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Langley, J., Samaranayaka, A., Davie, G. & Campbell, A. J. Age, cohort and period effects on hip fracture incidence: analysis and predictions from New Zealand data 1974–2007. Osteoporos Int 22, 105–111 (2010).

Maalouf, G. et al. Epidemiology of hip fractures in Lebanon: A nationwide survey. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 99, 675–680 (2013).

Lewiecki, M. E. et al. Hip fracture trends in the United States, 2002 to 2015. Osteoporos Int 22, 465 (2017).

Ettinger, B., Black, D. M., Dawson-Hughes, B., Pressman, A. R. & Melton, L. J. Updated fracture incidence rates for the US version of FRAX. Osteoporos Int 21, 25–33 (2010).

Abrahamsen, B. & Vestergaard, P. Declining incidence of hip fractures and the extent of use of anti-osteoporotic therapy in Denmark 1997-2006. Osteoporos Int 21, 373–380 (2010).

Karacić, T. P. & Kopjar, B. Hip fracture incidence in Croatia in patients aged 65 years and more. Lijec Vjesn 131, 9–13 (2009).

Leal, J. et al. Impact of hip fracture on hospital care costs: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 27, 549–558 (2015).

Kanis, J. A. et al. A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23, 2239–2256 (2012).

Marques, A., Lourenço, Ó., da Silva, J. A. P. & Portugal, O. B. O. T. P. W. G. F. T. S. O. T. B. O. H. F. I. The burden of osteoporotic hip fractures in Portugal: costs, health related quality of life and mortality. Osteoporos Int 26, 2623–2630 (1BC).

Tan, L. T., Wong, S. J. & Kwek, E. B. Inpatient cost for hip fracture patients managed with an orthogeriatric care model in Singapore. smedj 58, 139–144 (2017).

Lyons, A. R. Clinical outcomes and treatment of hip fractures. Am. J. Med. 103, 51S–63S– discussion 63S–64S (1997).

Panula, J. et al. Mortality and cause of death in hip fracture patients aged 65 or older - a population-based study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 12, 105 (2011).

Lizaur-Utrilla, A. et al. Early surgery within 2 days for hip fracture is not reliable as healthcare quality indicator. Injury 47, 1530–1535 (2016).

Schnell, S., Friedman, S. M., Mendelson, D. A., Bingham, K. W. & Kates, S. L. The 1-year mortality of patients treated in a hip fracture program for elders. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 1, 6–14 (2010).

Zuckerman, J. D. Hip fracture. N Engl J Med 334, 1519–1525 (1996).

Morrison, R. S., Chassin, M. R. & Siu, A. L. The medical consultant’s role in caring for patients with hip fracture. Ann. Intern. Med. 128, 1010–1020 (1998).

Parker, M. & Johansen, A. Hip fracture. BMJ 333, 27–30 (2006).

Haleem, S., Lutchman, L., Mayahi, R., Grice, J. E. & Parker, M. J. Mortality following hip fracture: trends and geographical variations over the last 40 years. Injury 39, 1157–1163 (2008).

Tolppanen, A.-M., Taipale, H., Tanskanen, A., Tiihonen, J. & Hartikainen, S. Comparison of predictors of hip fracture and mortality after hip fracture in community-dwellers with and without Alzheimer’s disease - exposure-matched cohort study. BMC Geriatr 16, 204 (2016).

Haentjens, P. et al. Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann. Intern. Med. 152, 380–390 (2010).

Silvia Andueza Robustillo, V., Juchno, P., Marcui, M. & Wronsk, A. Eurostat Demography Report - Short Analytical Web Note 3/2015. 2015.

Xu, J., Murphy, S., Kenneth, D., Kochanek, M. & Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2015. NCHS Data Brief, No 267. 2016.

OECD. Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators. 1–220 (2015).

Carpintero, P. Complications of hip fractures: A review. WJO 5, 402–11 (2014).

Roberts, K. C., Brox, W. T., Jevsevar, D. S. & Sevarino, K. Management of hip fractures in the elderly. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 23, 131–137 (2015).

National Guideline C. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on management of hip fractures in the elderly. 2014.

NICE. Hip fracture: management, Clinical guideline [CG124]. 2014.

Bhandari, M. & Swiontkowski, M. Management of Acute Hip Fracture. N Engl J Med 377, 2053–2062 (2017).

Orosz, G. M. et al. Association of timing of surgery for hip fracture and patient outcomes. JAMA 291, 1738–1743 (2004).

Parker, M. J. & Pryor, G. A. The timing of surgery for proximal femoral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 74, 203–205 (1992).

Smektala, R. et al. The effect of time-to-surgery on outcome in elderly patients with proximal femoral fractures. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 9, 387–9 (2008).

Simunovic, N. et al. Effect of early surgery after hip fracture on mortality and complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. 182, 1609–1616 (2010).

Klestil, T. et al. Immediate versus delayed surgery for hip fractures in the geriatric population. Available at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017058216. (Accessed: 29 January 2018).

Klestil, T. et al. Immediate versus delayed surgery for hip fractures in the elderly patients: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 6, 164 (2017).

Klestil, T. et al. Immediate versus delayed surgery for hip fractures in the elderly patients: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0559-7 (2017).

Wells, G. et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. (Accessed: 14 June 2018).

Falck-Ytter, Y., Schünemann, H. & Guyatt, G. AHRQ series commentary 1: rating the evidence in comparative effectiveness reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63, 474–475 (2010).

Zhang, J. & Yu, K. What’s the Relative Risk? JAMA 280, 1690–1691 (1998).

Dailiana, Z. et al. Surgical treatment of hip fractures: factors influencing mortality. 1–6 (2017).

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 (2003).

Higgins, J. P. T. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21, 1539–1558 (2002).

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Trpeski, S., Kaftandziev, I. & Kjaev, A. The effects of time-to-surgery on mortality in elderly patients following hip fractures. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki) 34, 115–121 (2013).

Crego-Vita, D., Sanchez-Perez, C., Gomez-Rico, J. A. O. & de Arriba, C. C. Intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly. Do we know what is important? Injury 48, 695–700 (2017).

Rae, H. C., Harris, I. A., McEvoy, L. & Todorova, T. Delay to surgery and mortality after hip fracture. ANZ J Surg 77, 889–891 (2007).

Siegmeth, A. W., Gurusamy, K. & Parker, M. J. Delay to surgery prolongs hospital stay in patients with fractures of the proximal femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br 87, 1123–1126 (2005).

Moran, C. G., Wenn, R. T., Sikand, M. & Taylor, A. M. Early mortality after hip fracture: is delay before surgery important? The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 87, 483–489 (2005).

Dorotka, R., Schoechtner, H. & Buchinger, W. The influence of immediate surgical treatment of proximal femoral fractures on mortality and quality of life. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 85, 1107–1113 (2003).

Elliott, J. et al. Predicting survival after treatment for fracture of the proximal femur and the effect of delays to surgery. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 56, 788–795 (2003).

Smektala, R., Wenning, M. & Luka, M. Early surgery after hip para-articular femoral fracture. Results of a prospective study of surgical timing in 161 elderly patients. Zentralbl Chir 125, 744–749 (2000).

Muhm, M., Arend, G., Ruffing, T. & Winkler, H. Mortality and quality of life after proximal femur fracture—effect of time until surgery and reasons for delay. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 39, 267–275 (2013).

Mariconda, M. et al. The determinants of mortality and morbidity during the year following fracture of the hip: a prospective study. Bone Joint J 97-B, 383–390 (2015).

Bretherton, C. P. & Parker, M. J. Early surgery for patients with a fracture of the hip decreases 30-day mortality. Bone Joint J 97-B, 104–108 (2015).

Hapuarachchi, K. S., Ahluwalia, R. S. & Bowditch, M. G. Neck of femur fractures in the over 90s: a select group of patients who require prompt surgical intervention for optimal results. J Orthopaed Traumatol 15, 13–19 (2013).

Poh, K. S. & Lingaraj, K. Complications and their risk factors following hip fracture surgery. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 21, 154–157 (2013).

Kim, S.-M. et al. Prediction of survival, second fracture, and functional recovery following the first hip fracture surgery in elderly patients. Bone 50, 1343–1350 (2012).

Pioli, G. et al. Older People With Hip Fracture and IADL Disability Require EarlierSurgery. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Science 67, 1272–1277 (2012).

Vidán, M. T. et al. Causes and effects of surgical delay in patients with hip fracture: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 155, 226–233 (2011).

Oztürk, A. et al. The risk factors for mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: postoperative one-year results. smedj 51, 137–143 (2010).

Vertelis, A., Robertsson, O., Tarasevicius, S. & Wingstrand, H. Delayed hospitalization increases mortality in displaced femoral neck fracture patients. Acta Orthopaedica 80, 683–686 (2009).

Yonezawa, T., Yamazaki, K., Atsumi, T. & Obara, S. Influence of the timing of surgery on mortality and activity of hip fracture in elderly patients. Journal of Orthopaedic Science 14, 566–573 (2009).

Al-Ani, A. N. et al. Early Operation on Patients with a Hip Fracture Improved the Ability to Return to Independent Living. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 90, 1436–1442 (2008).

Butler, A., Hahessy, S. & Condon, F. The effect of time to surgery on functional ability at six weeks in a hip fracture population in Mid-West Ireland. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing 26, 36–42 (2017).

Kelly-Pettersson, P. et al. Waiting time to surgery is correlated with an increased risk of serious adverse events during hospital stay in patients with hip-fracture: A cohort study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 69, 91–97 (2017).

Maggi, S. et al. A multicenter survey on profile of care for hip fracture: predictors of mortality and disability. Osteoporos Int 21, 223–231 (2010).

Pajulammi, H. M., Pihlajamäki, H. K., Luukkaala, T. H. & Nuotio, M. S. Pre- and perioperative predictors of changes in mobility and living arrangements after hip fracture—A population-based study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 61, 182–189 (2015).

Pajulammi, H. M., Luukkaala, T. H., Pihlajamäki, H. K. & Nuotio, M. S. Decreased glomerular filtration rate estimated by 2009 CKD-EPI equation predicts mortality in older hip fracture population. Injury 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2016.04.028 (2016).

Pioli, G. et al. Time to surgery and rehabilitation resources affect outcomes in orthogeriatric units. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 55, 316–322 (2011).

Pajulammi, H. M. et al. The Effect of an In-Hospital Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment on Short-Term Mortality During Orthogeriatric Hip Fracture Program—Which Patients Benefit the Most? 8, 183–191 (2017).

Shiga, T., Wajima, Z. & Ohe, Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth 55, 146–154 (2008).

Khan, S. K., Kalra, S., Khanna, A., Thiruvengada, M. M. & Parker, M. J. Timing of surgery for hip fractures: A systematic review of 52 published studies involving 291,413 patients. Injury 40, 692–697 (2009).

Lawrence, J. E., Fountain, D. M., Cundall-Curry, D. J. & Carrothers, A. D. Do Patients Taking Warfarin Experience Delays to Theatre, Longer Hospital Stay, and Poorer Survival After Hip Fracture? Clin Orthop Relat Res 475, 273–279 (2016).

Muhm, M. et al. Length of hospital stay for patients with proximal femoral fractures. 119, 560–569 (2014).

Cha, Y.-H. et al. Effect of causes of surgical delay on early and late mortality in patients with proximal hip fracture. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 137, 625–630 (2017).

Hip Fracture Accelerated Surgical Treatment and Care Track (HIP ATTACK) Investigators. Accelerated care versus standard care among patients with hip fracture: the HIP ATTACK pilot trial. CMAJ 186, E52–60 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandra Hummel and Sabine Siebenhandl for administrative support throughout the project and Emma Persad for proof reading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.K. conducted systematic literature searches. T.K., C.S., C.R., B.W., B.N., G.W. reviewed records for inclusion, abstracted data, contacted authors, and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. B.N., G.G., and G.W. conducted meta-analyses. T.K., C.S., C.R., B.N., G.W., I.K. drafted the manuscript. G.G., S.N., M.L. critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klestil, T., Röder, C., Stotter, C. et al. Impact of timing of surgery in elderly hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 8, 13933 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32098-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32098-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Predictive value of the systemic immune-inflammation index on one-year mortality in geriatric hip fractures

BMC Geriatrics (2024)

-

Risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2024)

-

Outcomes in very elderly ICU patients surgically treated for proximal femur fractures

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Use of direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) delays surgery and is associated with increased mortality in hip fracture patients

European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (2024)

-

Association between anesthesia technique and death after hip fracture repair for patients with COVID-19

Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.