Abstract

Non-magnetic (NM) metals with strong spin-orbit coupling have been recently explored as a probe of interface magnetism on ferromagnetic insulators (FMI) by means of the spin Hall magnetoresistance (SMR) effect. In NM/FMI heterostructures, increasing the spin mixing conductance (SMC) at the interface comes as an important step towards devices with maximized SMR. Here we report on the study of SMR in Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers at cryogenic temperature, and identify a strong dependence of the determined real part of the complex SMC on the interface roughness. We tune the roughness of the Pt/Fe3O4 interface by controlling the growth conditions of the Fe3O4 films, namely by varying the thickness, growth technique, and post-annealing processes. Field-dependent and angular-dependent magnetoresistance measurements sustain the clear observation of SMR. The determined real part of the complex SMC of the Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers ranges from 4.96 × 1014 Ω−1 m−2 to 7.16 × 1014 Ω−1 m−2 and increases with the roughness of the Fe3O4 underlayer. We demonstrate experimentally that the interface morphology, acting as an effective interlayer potential, leads to an enhancement of the spin mixing conductance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, spin currents have been a topic of intense scientific research because of its potential application in ultra-low power information technologies1,2,3,4,5,6. In this regard, heterostructures of non-magnetic (NM) metals with strong spin-orbit coupling (SOC) and ferromagnetic insulators (FMI) have emerged as a platform where spin currents can be used, among other spin-related applications7,8,9, to probe interface magnetism10,11. In NM/FMI bilayers, the coexistence of the spin Hall effect (SHE), inverse spin Hall effect (ISHE), and the magnetic proximity of the FMI leads to the spin Hall magnetoresistance (SMR) effect12,13. The SMR effect results from the spin currents generated in the NM metal via SHE that are reflected at the NM/FMI interface and converted back to a charge current via ISHE14. This additional contribution to the charge current leads to a characteristic dependence of the resistivity on the magnetization of the FMI. The spin accumulation and the spin mixing conductance (SMC) at the interface govern how efficiently the spins flow across it12, and consequently have an important role on the magnitude of the SMR12,15. SMR has been demonstrated in Pt/yttrium iron garnet (YIG) bilayers8,13, Pt/Co2FeSi16, Pt/CoFe2O410,11, Pt/Fe3O415,17, among others15,17,18, with Pt being used as model NM metal due to its large spin Hall angle19,20,21,22.

Within the SMR framework, maximizing the magnetoresistance requires increasing the efficiency with which spin currents flow across the NM/FMI interface8,9,12,15,23,24,25,26,27. In this regard, it has been reported that the SMC of an NM/FMI interface can be enhanced by increasing the magnetic density at the interface. This can be achieved by inserting atomically thin magnetic interlayers27,28,29, changing the elementary composition, or implanting magnetic impurities at the interface30,31. It has also been predicted that interface morphology can play a key role in the SMC, with first principle calculations of NM/ferromagnetic (FM) heterostructures indicating a generalized increase of the real part of the SMC, Gr, with increasing roughness32. However, there are few reports clarifying the relation between these two parameters32,33.

In this work, we present the study of SMR in Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers at cryogenic temperatures and identify a dependence of the SMC on the interface morphology. To clarify that dependence, we tune the morphology of the Pt/Fe3O4 interface by controlling the growth conditions of the Fe3O4 films, including the film thickness, growth technique, and post-annealing processes, while maintaining consistent magnetic and structural properties of the films. The surface morphology of the Fe3O4 is characterized and quantified using atomic force microscopy (AFM). Field-dependent and angular-dependent magnetoresistance (FDMR and ADMR) measurements support the observation of SMR in the Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers. Employing the theory of SMR in NM/FMI heterostructures, we determine the real part of the SMC at the Pt/Fe3O4 interface and demonstrate that the morphology of the Fe3O4 film plays a determinant role in its magnitude.

Results

Fe3O4 surface morphology and electrical characterization of Pt/Fe3O4 Hall bars

The fabrication of the Pt/Fe3O4 Hall bars followed two distinct procedures (see Methods for additional details). In samples A, A1, B, and B1, the Fe3O4 films were deposited on MgO(100) substrates using oxide-molecular beam epitaxy (oxide-MBE). In sample C, the Fe3O4 film was deposited using RF-magnetron sputtering on a MgO buffer layer prepared by ultra-high vacuum (UHV)-MBE. The Fe3O4 films are 4-nm thick for samples A and A1, 6-nm thick for samples B and B1, and 40-nm thick for sample C. Samples A1 and B1 were additionally subject to a post-annealing process at 300 °C for 3 hours to drive inter-grain diffusion and coalescence, resulting in the change of the Fe3O4 roughness. Sample C was annealed at 400 °C for 2 hours after the deposition of the Fe3O4. The Pt layers were deposited onto the Fe3O4 films by UHV-MBE using shadow masking techniques to pattern six-terminal Hall bars with a 50-μm-wide and 400-μm-long channel. The thickness of the Pt films was kept within the spin diffusion length of Pt and minimized down to the experimental limit where the films formed continuous and conductive layers (2 to 3 nm thick).

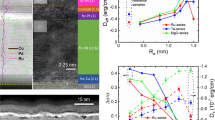

To study the relationship between the interface morphology of the Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers and the SMR, we started by characterizing the roughness of the Fe3O4 films using AFM and the temperature dependence of the resistivity of the Pt/Fe3O4 Hall bars. In Fig. 1a,b, we show AFM scans of the smoothest and roughest Fe3O4 films, namely of samples A and C, respectively (see Sup. Fig. S1 for the AFM scans of all samples). The AFM scan of the Fe3O4 film of sample A shows a smooth surface morphology, with root-mean square (RMS) roughness of 0.42 nm, and an average grain size of 32 nm. The AFM image of the Fe3O4 film of sample C shows a RMS roughness of 1.1 nm and an average grain size of 40 nm. Table 1 summarizes the results obtained using AFM for the five samples. The five different growth conditions (samples A, A1, B, B1, and C) allowed us to achieve a surface roughness of the Fe3O4 films that ranges from 0.42 nm to 1.1 nm, while maintaining consistent ferromagnetic and structural properties of the films. SMR is sensitive to the structural details at the interface, and ensuring that the films have comparable properties is important for the evaluation of the SMR signals of the different samples. The Fe3O4 films deposited using both deposition techniques are highly textured and have similar magnetic moment per unit volume (see Sup. Fig. S2 for the magnetic hysteresis loops, and Sup. Fig. S3 for the structural characterization of the films).

Regarding the electrical characterization of the samples, Fig. 1c,d show the temperature dependence of the longitudinal resistivity, ρ, of the Pt/Fe3O4 Hall bars for the samples with the smoothest and roughest Fe3O4 films, namely samples A and C. The resistivity measurements were performed from T = 300 K down to T = 77 K, within the experimentally accessible conditions using liquid nitrogen cooling (see Methods). In Fig. 1c, the 3-nm-thick Pt film of sample A dominates the transport behavior over the 4-nm-thick Fe3O4 film, with the resistivity of the sample exhibiting a metallic temperature dependence. Sample C (Fig. 1d) exhibits a semiconductor-like temperature dependence because of the extra conduction channels introduced by the 40-nm-thick Fe3O4 film that compete with the shaped Pt layer (see Sup. Fig. S4 for the temperature dependence of Fe3O4 films). However, at temperatures close to the Verwey transition of the Fe3O4 (TV = 125 K)34,35, the contribution of the Fe3O4 channel greatly decreases, and Pt dominates the conductance of the sample. For this reason, the resistivity for both cases (samples A and C) converges at ~ 7 × 10−5 Ω cm at temperatures below 100 K, on par with the resistivity reported for high-quality Pt films used in SMR experiments of other works10,15. The electrical characterization strongly suggests that for the surface roughness present in our samples, 2- to 3-nm-thick Pt layers are enough to ensure the coverage of the surface, forming high-quality, conducting, and metallic films. This is an important feature, since in the framework of SMR the non-magnetic metal thickness should be thin enough to allow for the generation of a spin accumulation at the interface with the FMI. The insulating state of the Fe3O4 film at low temperatures leads us to focus the study of the SMR at temperatures below the Verwey transition of Fe3O4, namely at T = 77 K.

Spin Hall magnetoresistance of Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers

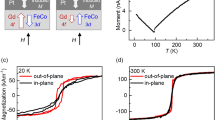

According to SMR theory, the longitudinal resistivity ρ in a NM/FMI bilayer can be formulated as10,12

where ρ0 is a constant resistivity offset, Δρ is the magnitude of the resistivity change, and my is the y-component of the unitary magnetization vector, \(\hat{{\boldsymbol{m}}}=({m}_{x},{m}_{y},{m}_{z})\), in the direction transverse to the charge current and parallel to the film plane. In Fig. 2a,b, we depict qualitatively the SMR mechanism in a NM/FMI bilayer for the cases when my = 0 and my = 1, respectively. For my = 0, the spin current is transmitted across the interface, and when my = 1, the reflected spin current generates an additional charge current via ISHE that decreases the total resistivity12,14. In Fig. 2c, we show an optical microscope image of the Pt Hall bar used to determine the dependence of the longitudinal resistivity on the magnetization of the Fe3O4 underlayer. The current, I, of 100 μA, is injected along the Hall bar and the voltage drop, Vxx, is measured at two of the lateral arms along the current path, separated by a length, L, of 400 μm. The resistivity is determined from the expression \(\,\rho ={V}_{xx}{t}_{NM}W/(LI)\), where W is the width of the channel (50 μm). In our samples, we define the x-axis parallel to the current injection path, the z-axis normal to the film surface, and the y-axis perpendicular to both following a right-hand rule.

Sketch of the SMR mechanism in a NM/FMI heterostructure. A charge current Je flowing in the NM with strong SOC is converted into a transverse spin current via SHE, leading to a spin accumulation at the NM/FMI interface. The spin current will be (a) absorbed or (b) reflected depending on the relative orientation of the magnetization of the FMI and the spin polarization of the spin current. (c) Optical microscopy image of the six-terminal Pt Hall bar on the Fe3O4 layer, with an indication of the x, y, and z-axes. (d) Magnetic field dependence of the longitudinal resistivity of sample A, (e) sample A1, and (f) sample C at T = 77 K, for an external magnetic field applied along the x, y, and z-axes.

To confirm the presence of SMR in our samples, we performed FDMR and ADMR measurements. Figure 2d,e, and f show the FDMR of samples A, A1, and C, respectively, at T = 77 K, with the external magnetic field applied parallel to the x, y, and z-axes (see Sup. Fig. S5 for the FDMR of samples B and B1). As stated before, at temperatures lower than TV, the resistivity of Fe3O4 is higher than the resistivity of Pt34, minimizing the current shunting through the Fe3O4 layer and respective anisotropic magnetoresistance effects17. Starting with sample A (Fig. 2d), when the magnetic field is applied parallel to the x- and z-axis, H // x and H // z, respectively, the resistivity increases with the increase of the external magnetic field, saturating in both cases at ρ ∼ 690.15 × 10−7 Ω cm. Noticeably, when the magnetic field is applied along the z-axis, H // z, the resistivity saturates at higher fields than for the case when H // x. This is because of the additional contribution of the shape anisotropy of the Fe3O4 film. The SMR theory fits well both cases. The decrease of the y-component of the magnetization (with the increase of the external magnetic field) is accompanied by an increase of the resistivity, which saturates once the magnetization saturates along the x and z-axes, as expected from Eq. 1. When the magnetic field is applied along the y-axis, H // y, the resistivity decreases with the increase of the magnetic field, saturating at ρ ∼ 689.85 × 10−7 Ω cm. Again, this goes in line with the expectation from Eq. 1 that the resistivity should decrease with the increase of the y-component of the magnetization, saturating once the magnetization saturates36,37. The data obtained from the three FDMR measurements strongly suggests the presence of SMR. Evaluating the data according to Eq. 1, we find for sample A that ρ0 ∼ 689.85 × 10−7 Ω cm and Δρ/ρ0 = 4.6 ± 0.2 × 10−4. Similar values have been determined on previous works on Pt/YIG and Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers15. For samples A1 and C, the FDMR is similar to what was observed for sample A, with the remarking difference being the values of ρ0 and Δρ/ρ0 extracted for both cases. For sample A1, ρ0 ∼ 569.89 × 10−7 Ω cm and Δρ/ρ0 = 4.3 ± 0.1 × 10−4, and for sample C, ρ0 ∼ 699.85 × 10−7 Ω cm and Δρ/ρ0 = 4.1 ± 0.2 × 10−4. We shall analyze in the Discussion section the implications of these results.

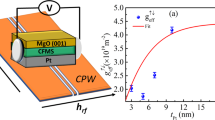

An additional method to demonstrate and confirm the presence of SMR is to perform ADMR measurements15,38. In ADMR measurements, one sets the magnitude of the applied external magnetic field such that the magnetization of the FMI layer saturates in its direction (see Sup. Fig. S2 for the hysteresis loops), and then measures the resistivity as a function of the angle formed between the external magnetic field and the sample. Figure 3a depicts the three different geometries explored, with the rotation of the external magnetic field in the planes formed by the x-y, y-z, and x-z axes quantified by the α, β, and γ angles, respectively (when α = 0, the magnetization lies along the x-axis, and when β, γ = 0 the magnetization lies along the z-axis). Since the y-component of the magnetization should vary only in the cases of an angular dependence in the x-y and y-z planes, the angular dependence in the x-z plane should show no significant change in resistivity. Figure 3b shows the consistency of the experimental data with this argument based on SMR for sample A. The resistivity shows a minimum when the magnetization lies along the y-axis (α, β = 90°, 270°), and a maximum when the y-component of the magnetization vanishes (α, β = 0°, 180°, 360°), with overall dependence proportional to the squared cosine of the angles α and β, as expected from Eq. 1. Both FDMR and ADMR measurements strongly support the observation of SMR in our Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers.

(a) Sketch of the three geometries used for the angular-dependent magnetoresistance measurements in the planes defined by the x-y, y-z, and x-z axes, corresponding to angles α, β, and γ, respectively (top-to-bottom). When α = 0, the field is aligned with the x-axis; when β, γ = 0, the field is aligned with the z-axis. (b) Angular dependence of the resistivity of sample A at T = 77 K, for a fixed external magnetic field H = 15 kOe for the three geometries considered. The green solid line is a guide to the eye for a squared cosine angular dependence.

Discussion

The SMR ratio Δρ/ρ0 relates to the spin transporting parameters of the NM/FMI bilayer by the expression12,15

where θSH, NM is the spin Hall angle, λNM is the spin diffusion length, σNM is the conductivity, tNM is the thickness of the NM layer, and Gr is the real part of the interface SMC. To determine the interface spin transport parameters between Pt and Fe3O4, one needs a reliable estimate of λNM and θSH, NM of Pt. For this, we followed the work of Sagasta et al.39 where it is established that the spin relaxation in Pt follows the Elliot-Yafet mechanism, translating into a linear dependence of the spin diffusion length on the conductivity. In the work, the agreement of the spin transporting properties of Pt with the resistivity of devices fabricated with different growth techniques and by different groups provides us the confidence to estimate λPt and θSH, Pt for our samples. According to the conductivity of our Pt films (between 1.43 × 104 Ω−1 cm−1 and 2.17 × 104 Ω−1 cm−1), we estimate the λPt to range from 1.4 nm to 2.7 nm and θSH, Pt to be ~ 0.056, also in agreement with what was determined by other groups using spin pumping and inverse spin Hall experiments9. Using Eq. 1 and Eq. 2, we summarize in Table 2 the SMR data obtained for all the samples considered in this work. The determined Gr of all samples ranges from 4.96 × 1014 Ω−1 m−2 to 7.16 × 1014 Ω−1 m−2, similar to what has been reported in other NM/FMI bilayers systems, namely Pt/YIG8,10,13,15,40 (1.2 × 1013 Ω−1 m−2 to 1.3 × 1015 Ω−1 m−2), Ag/YIG41, (4.5 × 1014 Ω−1 m−2), or Au/YIG42 (1.9 × 1014 Ω−1 m−2). The dependence of Gr on the interface roughness becomes clear in Fig. 4, where we plot the calculated Gr of all samples versus the respective RMS of the Fe3O4 films determined by AFM. Within the explored RMS, Gr increases with the increase of roughness. Our data suggests that the reflection/transmission of spins at the interface is significantly altered by the morphology of the Fe3O4 underlayer. While it has been shown before that the crystalline texture of single crystal FMIs has an effect on the SMC10,41, (demonstrating how sensitive the SMC is to the atomic arrangement at the surface), it remained to be demonstrated a clear effect of the surface roughness. Using polycrystalline Fe3O4 films with grain size orders of magnitude lower than the width and length of the channel of the Hall bars used in this work, we expect the differences in the atomic arrangement at the surface of each individual grain to be averaged out for the whole device. As stated before, interface roughness has been proposed to enhance the SMC in NM/FM heterostructures by introducing an effective potential from a composite NM1−xFMx interlayer at the interface32. Although we cannot decouple a possible interface-induced spin Hall angle contribution to the SMR33, the generalized observation remains that rougher interfaces lead to an increase of Gr.

In summary, we have demonstrated the SMR effect in Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers at cryogenic temperatures. From the analysis of the observed SMR, we have shown that the determined Gr strongly depends on the RMS roughness of the Fe3O4 film, indicating that the interface morphology of NM/FMI heterostructures is an important parameter contributing to the SMC. Our observations are in-line with previous predictions that the SMC can be enhanced by treating interface roughness as an effective interlayer potential. Since SMC is a critical parameter for various spin-related phenomena in NM/FMI heterostructures, our work suggests that engineering the surface roughness of polycrystalline FMI is a relevant and significant method not only for SMR-based devices, but for device structures that rely on magnetic insulators.

Methods

Sample Preparation

Two growth techniques were employed for the deposition of Fe3O4 films. In samples A, A1, B, B1, the Fe3O4 thin films were deposited on MgO(100) substrates using oxide-molecular beam epitaxy (oxide-MBE) (VG Semicon, Inc.). The MgO(100) substrates were prepared by cleaning in a bath of methanol at 60 °C and drying with N2 gas. Afterward, the cleaned substrates were transferred into the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber, and pre-heated at 600 °C for 30 minutes to remove residual impurities. The substrate was then cooled and maintained at 400 °C for the growth of the thin film. Iron high-temperature effusion cells and oxygen cracking cells were used to grow the Fe3O4 thin films at a partial oxygen pressure of 10−6 Torr. To control the thickness of the films, the evaporation rates were determined using a quartz crystal thickness monitor. The crystal quality during growth was monitored by RHEED (reflection high-energy electron diffraction).

For sample C, the multi-layered architecture was prepared in-situ in a home-built UHV-clusters deposition system equipped with MBE and radio-frequency (RF)-magnetron sputtering techniques. The Fe3O4 thin film was deposited using magnetron sputtering on an MgO buffer layer prepared by UHV-MBE. First, a 5-nm-thick layer of Ta was deposited on a SiO2/Si(100) substrate by RF-magnetron sputtering, followed by the growth of a 5-nm-thick layer of MgO using UHV-MBE at a temperature of 200 °C, with a deposition rate of 0.0028 nm/s and at a pressure of 2.5 × 10−9 Torr. Afterwards, the sputtering of Fe3O4 was prepared at a base pressure of 2.3 × 10−9 Torr, with a flow of 33 sccm of Ar-gas ensuring a stable plasma. The as-grown Fe3O4 films were annealed at 400 °C for 2 hours in vacuum.

In all cases, the Pt Hall bars were deposited in an UHV-MBE chamber by electron-beam evaporation at room temperature, using shadow masking, with a deposition rate of 0.016 nm/s, and at a base pressure of 2.0 × 10−10 Torr.

Surface, structural, magnetic, and electrical characterization

The surface morphology, and the magnetic and structural properties of the Fe3O4 films were characterized using atomic force microscopy (EasyScan2, Nanosurf), vibration sample magnetometry (Quantum Design magnetic property measurement system, MPMS-5XL), and X-ray diffraction and reflectivity (Bruker Discover D8), respectively.

The electrical characterization was performed in a variable-temperature probe station using nitrogen cooling down to 77 K, and with magnetic fields up to 10 kOe. A Keithley 6220 was used as a current source and a Keithely 2182 A as a nanovoltmeter. The angular-dependent magnetoresistance measurements were performed in a Quantum Design physical property measurement system with an in-built low-frequency alternate-current lock-in board. For both cases, standard four-probe measurement schemes were used.

References

Joshi, V. K. S. A contemporary review of emerging electronics devices. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 19, 1503–1513, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2016.05.002 (2016).

Jungwirth, T., Wunderlich, J. & Olejnik, K. Spin Hall effect devices. Nat Mater 11, 382–390, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3279 (2012).

Miron, I. M. et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature 476, 189–193, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10309 (2011).

Demidov, V. E. et al. Magnetic nano-oscillator driven by pure spin current. Nat Mater 11, 1028–1031, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3459 (2012).

Ribeiro, M., Power, S. R., Roche, S., Hueso, L. E. & Casanova, F. Scale-invariant large nonlocality in polycrystalline graphene. Nat Commun 8, 2198, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02346-x (2017).

Yan, W. et al. Large room temperature spin-to-charge conversion signals in a few-layer graphene/Pt lateral heterostructure. Nat Commun 8, 661, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00563-y (2017).

Ramos, R. et al. Observation of the spin Seebeck effect in epitaxial Fe3O4 thin films. Applied Physics Letters 102, 072413, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4793486 (2013).

Qiu, Z. et al. Spin mixing conductance at a well-controlled platinum/yttrium iron garnet interface. Applied Physics Letters 103, 092404, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4819460 (2013).

Rojas-Sanchez, J. C. et al. Spin pumping and inverse spin Hall effect in platinum: the essential role of spin-memory loss at metallic interfaces. Phys Rev Lett 112, 106602, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.106602 (2014).

Isasa, M. et al. Spin Hall magnetoresistance at Pt/CoFe2O4 interfaces and texture effects. Applied Physics Letters 105, 142402, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4897544 (2014).

Isasa, M. et al. Spin Hall Magnetoresistance as a Probe for Surface Magnetization inPt/CoFe2O4 Bilayers. Physical Review Applied 6, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.6.034007 (2016).

Chen, Y.-T. et al. Theory of spin Hall magnetoresistance. Physical Review B 87, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.144411 (2013).

Nakayama, H. et al. Spin Hall magnetoresistance induced by a nonequilibrium proximity effect. Phys Rev Lett 110, 206601, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.206601 (2013).

Sinova, J., Valenzuela, S. O., Wunderlich, J., Back, C. H. & Jungwirth, T. Spin Hall effects. Reviews of Modern Physics 87, 1213–1260, https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.87.1213 (2015).

Althammer, M. et al. Quantitative study of the spin Hall magnetoresistance in ferromagnetic insulator/normal metal hybrids. Physical Review B 87, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.224401 (2013).

Huang, X. et al. Spin Hall magnetoresistance in Co2FeSi/Pt thin films: dependence on Pt thickness and temperature. J Phys Condens Matter 28, 476006, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/28/47/476006 (2016).

Ding, Z. et al. Spin Hall magnetoresistance inPt/Fe3O4 thin films at room temperature. Physical Review B 90, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.90.134424 (2014).

Vlietstra, N., Shan, J., Castel, V., Van Wees, B. J. & Ben Youssef, J. Spin-Hall magnetoresistance in platinum on yttrium iron garnet: Dependence on platinum thickness and in-plane/out-of-plane magnetization. Physical Review B 87, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.184421 (2013).

Uchida, K. et al. Observation of the spin Seebeck effect. Nature 455, 778–781, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07321 (2008).

Nguyen, H. Y. T., Pratt, W. P. & Bass, J. Spin-flipping in Pt and at Co/Pt interfaces. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 361, 30–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2014.02.058 (2014).

Zhang, W. et al. Determination of the Pt spin diffusion length by spin-pumping and spin Hall effect. Applied Physics Letters 103, 242414, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4848102 (2013).

Kondou, K., Sukegawa, H., Mitani, S., Tsukagoshi, K. & Kasai, S. Evaluation of Spin Hall Angle and Spin Diffusion Length by Using Spin Current-Induced Ferromagnetic Resonance. Applied Physics Express 5, 073002, https://doi.org/10.1143/apex.5.073002 (2012).

Zhang, W., Wu, T., Peng, B. & Zhang, W. Resistivity dependence of the spin mixing conductance and the anisotropic magnetoresistance in permalloy. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 696, 234–238, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.11.274 (2017).

Deorani, P. & Yang, H. Role of spin mixing conductance in spin pumping: Enhancement of spin pumping efficiency in Ta/Cu/Py structures. Applied Physics Letters 103, 232408, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4839475 (2013).

Czeschka, F. D. et al. Scaling behavior of the spin pumping effect in ferromagnet-platinum bilayers. Phys Rev Lett 107, 046601, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.046601 (2011).

Wang, H. L. et al. Scaling of spin Hall angle in 3d, 4d, and 5d metals from Y3Fe5O12/metal spin pumping. Phys Rev Lett 112, 197201, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.197201 (2014).

Yuasa, H., Tamae, K. & Onizuka, N. Spin mixing conductance enhancement by increasing magnetic density. AIP Advances 7, 055928, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4977496 (2017).

Kim, D.-H., Kim, H.-H. & You, C.-Y. Suppression of the spin pumping in Pd/Ni81Fe19 bilayers with nano-oxide layer. Applied Physics Letters 99, 072502, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3626593 (2011).

Mosendz, O., Pearson, J. E., Fradin, F. Y., Bader, S. D. & Hoffmann, A. Suppression of spin-pumping by a MgO tunnel-barrier. Applied Physics Letters 96, 022502, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3280378 (2010).

Laczkowski, P. et al. Large enhancement of the spin Hall effect in Au by side-jump scattering on Ta impurities. Physical Review B 96, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.140405 (2017).

Hahn, C. et al. Comparative measurements of inverse spin Hall effects and magnetoresistance in YIG/Pt and YIG/Ta. Physical Review B 87, dhttps://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.174417 (2013).

Zhang, Q., Hikino, S.-I. & Yunoki, S. First-principles study of the spin-mixing conductance in Pt/Ni81Fe19 junctions. Applied Physics Letters 99, 172105, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3657144 (2011).

Zhou, L., Grigoryan, V. L., Maekawa, S., Wang, X. & Xiao, J. Spin Hall effect by surface roughness. Physical Review B 91, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.91.045407 (2015).

Verwey, E. J. W. Electronic Conduction of Magnetite (Fe3O4) and its Transition Point at Low Temperatures. Nature 144, 327, https://doi.org/10.1038/144327b0 (1939).

Phase, D. M. et al. Raman study across Verwey transition of epitaxial Fe3O4 thin films on MgO (100) substrate grown by pulsed laser deposition. Journal of Applied Physics 100, 123703, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2403849 (2006).

Miao, B. F., Huang, S. Y., Qu, D. & Chien, C. L. Physical origins of the new magnetoresistance in Pt/YIG. Phys Rev Lett 112, 236601, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.236601 (2014).

Kim, J., Sheng, P., Takahashi, S., Mitani, S. & Hayashi, M. Spin Hall Magnetoresistance in Metallic Bilayers. Phys Rev Lett 116, 097201, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.097201 (2016).

Hui, Y. et al. Transport mechanism of the magnetoresistance effects in Ta/CoFe2O4 nanostructures. Applied Physics Letters 110, 192404, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4983171 (2017).

Sagasta, E. et al. Tuning the spin Hall effect of Pt from the moderately dirty to the superclean regime. Physical Review B 94, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.94.060412 (2016).

Castel, V., Vlietstra, N., Youssef, J. B. & Wees, B. J. V. Platinum thickness dependence of the inverse spin-Hall voltage from spin pumping in a hybrid yttrium iron garnet/platinum system. Applied Physics Letters 101, 132414, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4754837 (2012).

Jia, X., Liu, K., Xia, K. & Bauer, G. E. W. Spin transfer torque on magnetic insulators. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 96, 17005, https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/96/17005 (2011).

Burrowes, C. et al. Enhanced spin pumping at yttrium iron garnet/Au interfaces. Applied Physics Letters 100, 092403, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3690918 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Institute for Basic Science, Republic of Korea (IBS-R027-D1). N.J.L acknowledges the support from the National Research Council of Science & Technology (NST) grant (No. CAP-16-01-KIST) by the Korea government (MSIP). Part of this study has been performed using facilities at IBS Center for Correlated Electron Systems, Seoul National University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K.H.P. and T.H.K. designed the experiments. T.K.H.P., M.R., T.H.K., and J.H.P. performed the experiments, the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. V.Q.N. and S.C. carried out the sample preparation using oxide-MBE. A.M. contributed to the structural analysis of the samples using XRD and XRR techniques. N.J.L. and E.P. participated in the sample preparation using RF sputtering. K.H.K. and C.S.Y. measured the magnetic properties of the Fe3O4 films. All authors participated in the discussion of the results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. T.H.K. supervised the entire study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pham, T.K.H., Ribeiro, M., Park, J.H. et al. Interface morphology effect on the spin mixing conductance of Pt/Fe3O4 bilayers. Sci Rep 8, 13907 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31915-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31915-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The anisotropy of spin Hall magnetoresistance in Pt/YIG structures

Applied Physics A (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.