Abstract

The Arabidopsis histone deacetylase 6 (HDA6) mutant exhibits increased tolerance to drought stress by negatively regulating the expression of ALDH2B7 and PDC1. Therefore, it was logical to determine if transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing PDC1 or ALDH2B7 using a suitable promoter would also exhibit tolerance to drought stress. An analysis of published microarray data indicated the up-regulation of the TSPO gene, which encodes an outer membrane tryptophan-rich sensory protein (TSPO), by drought stress. RT-qPCR, as well as GUS analysis of the promoter, confirmed the up-regulation of TSPO by drought stress in Arabidopsis roots and shoots. Thus, the TSPO promoter was used to drive drought-responsive expression of ALDH2B7 and PDC1. RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that the expression of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 was up-regulated, relative to WT plants, by drought stress in homozygous pTSPO-PDC1 and pTSPO-ALDH2B7 plant lines. pTSPO-ALDH2B7 and pTSPO-PDC1 transgenic lines showed prolonged survival under drought stress. Microarray analyses revealed transcriptomic changes related to metabolism in pTSPO-PDC1 plants, indicating that selective regulation of metabolism may occur; resulting in the acquisition of drought stress tolerance. These results confirmed that TSPO promoter can be used to elevate the expression of acetic acid biosynthesis pathway genes; ensuring prolonged survival under drought stress in Arabidopsis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drought stress negatively impacts photosynthesis and plant growth and can ultimately result in reduced crop yield and enormous economic losses. As a result, the development of drought tolerant crops has received great attention and aims to mitigate the deleterious effects associated with drought stress on crop production. The molecular response to drought stress has been comprehensively characterized1,2, including the transcriptomic changes that occur in roots and shoots of soil grown, drought-stressed Arabidopsis plants3,4. These various analyses led to the identification of genes that are putatively involved in plant response to drought stress. Therefore, these data could be potentially utilized to genetically engineer drought tolerant plants by transforming plants with novel combinations of genes and promoters. In this regard, Arabidopsis histone deacetylase 6 (HDA6) mutants are tolerant to drought stress5,6. HDA6 negatively regulates the expression of PDC1 & ALDH2B7, as indicated by the up-regulated expression of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 in the hda6 mutant5.

In Arabidopsis, PDC1 and ALDH2B7 genes have functional roles in the acetic acid fermentation pathway (Fig. 1). Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) converts pyruvate into the Acetyl-Co enzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) and is termed the PDH pathway. Acetyl-CoA can also be synthesized by an alternative pathway in which PDH is bypassed. In this case, PDC proteins convert pyruvate to acetaldehyde, which is subsequently converted to acetate by ALDH enzymes7,8. The PDC family in Arabidopsis is comprised of 4 members (PDC1, PDC2, PDC3 & PDC4). PDC proteins convert pyruvate to acetaldehyde, and thus contribute to ethanol fermentation, as well as acetic acid production. PDC1 is 607 amino acids in length and is predicted to localize to the cytoplasm; although its localization has not been verified. Among the other PDC proteins in Arabidopsis, PDC1 shares 89% homology with PDC4, 88% with PDC3, and 82% with PDC2. Arabidopsis PDC proteins have been reported to play a role in ethanol fermentation9,10. Their role in acetate production through a PDH independent pathway, however, has never been verified or comprehensively discussed.

The acetic acid biosynthesis pathway in plants. Pyruvate is converted to acetaldehyde by PDC1 and the resultant acetaldehyde is converted to acetic acid by ALDH2B7. Acetaldehyde may also be converted to ethanol and vice versa. According to Rasheed et al. (2016a), genes shown in red were up-regulated in response to drought stress, while the genes shown in blue were down-regulated. *The expression of only the mitochondrial PDH-E1 alpha (AT1G01090) and beta (AT1G30120) subunits decreased significantly in response to drought stress.

The aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) superfamily is a diverse family of proteins controlling aldehyde metabolism. ALDH enzymes convert aldehydes to their corresponding carboxylic acids utilizing NAD+ or NADP+ as a cofactor to yield NADH or NADPH. In contrast to PDC family proteins, which are confined to plants and fungi, the ALDH family is ubiquitous in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms; including plants11. Aldehyde compounds play an essential role in several catabolic and biosynthetic pathways and also contribute to the maintenance of the cellular redox balance8,11,12,13. Plant ALDHs perform a diverse array of functions in many catabolic and biosynthetic pathways, including amino acid metabolism, glycolysis, and carnitine biosynthesis8,11,12. In plants, several studies have reported the up-regulation of ALDH genes in response to a variety of stress conditions. Overexpression of ALDH genes can increase stress tolerance14,15. In general, the expression of ALDH genes in Arabidopsis is not regulated by anoxia. Rather, the expression of ALDH2B7 is up-regulated in response to ABA application and dehydration; suggesting that ALDH may play a role in aerobic detoxification of acetaldehyde. Additionally, in response to stress, ALDH activity may occur independent of ethanol fermentation9.

Microarray analyses have indicated that the expression of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 are up-regulated by drought stress. These data, combined with the drought tolerant phenotype exhibited by the hda6 mutant and the enhanced drought tolerance that is induced by the exogenous application of acetic acid5, strongly suggest that plants expressing PDC1 or ALDH2B7 under the control of a suitable promoter could significantly enhance drought stress tolerance.

In order to be of practical utility, drought tolerant plants should not exhibit any undesirable phenotypes16,17. Avoiding undesirable, non-target, responses could be achieved by regulating the expression of genes that convey drought tolerance through the selection of a promoter that regulates the desired genes in a strict spatial and temporal manner. In this case, an ideal promoter should induce gene expression in roots and shoot organs specifically in response to drought stress, particularly during the early phase of drought stress. An analysis of recent microarray data indicated that the expression of a gene encoding a tryptophan-rich sensory protein (TSPO) is significantly up-regulated in roots and shoots during early drought stress3. TSPOs are small ubiquitous transmembrane proteins that are found in prokaryotes, plants, animals, and humans18. Arabidopsis TSPO localizes to the Golgi apparatus and the expression of the TSPO gene, as well as the accumulation of the protein, is strictly regulated by abiotic stresses and ABA19,20,21. These data indicate that the TSPO promoter could potentially be utilized for regulating genes in transgenic plants that convey drought tolerance. Thus, transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing PDC1 or ALDH2B7 genes under the control of the TSPO promoter (pTSPO-PDC1 or pTSPO-ALDH2B7) were developed. The resulting transgenic plants exhibited a significant increase in drought stress tolerance. These results demonstrate that the elevated expression of acetic acid biosynthesis pathway genes using a TSPO promoter can significantly enhance drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis plants.

Results

Analysis of drought-inducible expression of PDC1, ALDH2B7, and TSPO genes

In Arabidopsis, previously generated microarray data related to drought stress response were analyzed in order to evaluate the expression of the PDC and ALDH gene family3 (Table 1). Among the 14 members of the Arabidopsis ALDH genes, expression of ALDH2B7 was up-regulated during the 5th to 9th day in roots following a drought stress treatment, expression of ALDH7B4 and ALDH10A8 was up-regulated during the 7th to 9th day, and the expression of ALDH2B4 was up-regulated only on the 9th day. In shoots, the expression of ALDH2B4, ALDH2B7, and ALDH7B4 was also significantly up-regulated in response to drought stress. ALDH2B4 and ALDH2B7 are predicted to localize to mitochondria, while ALDH7B4 is a cytosolic enzyme (Table 1). ALDH2B4 and ALDH2B7 are also phylogenetically related to each other; resulting in a subclade with ALDH2C4 (Fig. S1). The expression levels of ALDH2B4 and ALDH2B7 were both significantly up-regulated in root tissue by drought stress, however, the up-regulation of ALDH2B7 occurred much earlier than ALDH2B4. RT-qPCR analysis further confirmed that ALDH2B7 expression is significantly up-regulated in roots and shoots of WT plants in response to drought stress (Fig. 2).

RT-qPCR confirmation of up-regulation of ALDH2B7, PDC1, and TSPO in response to drought stress in WT plants. (A) Expression of PDC1, (B) ALDH2B7, and (C) TSPO in shoots of Arabidopsis plants grown in ceramics soil. (D Expression of PDC1, (E) ALDH2B7, and (F) TSPO in roots of Arabidopsis plants grown in ceramics soil. An asterisk above a column indicates that the value is significantly different from day 0 based on a t-test (p < 0.05). n = 3.

Among the 4 members of Arabidopsis PDC family, expression of PDC1 was significantly up-regulated in roots and shoots in response to drought stress, while the expression of PDC2 in roots was only slightly up-regulated on the 9th day after drought stress (Table 1). The expression of TSPO was similarly up-regulated in roots and shoots by drought stress (Table 1). RT-qPCR analysis further confirmed the up-regulation of PDC1, ALDH2B7 and TSPO in roots and shoots in response to drought stress (Fig. 2).

GUS analysis of TSPO and PDC1 promoter activity

In Arabidopsis, TSPO is a small, intronless gene located on chromosome 2 (Fig. S2A). In contrast, PDC1 contains 5 exons, while ALDH2B7 is composed of 11 exons (Fig. S2B,C). A 1.4 kb promoter sequence upstream of the ATG start codon of TSPO was used to drive the expression of uidA which allowed for subsequent analysis by GUS staining (Fig. S2D). Although the GUS expression driven by TSPO promoter was not detected during vegetative growth under normal growth conditions (Fig. 3A,B), analysis of four independent transgenic lines revealed expression during the early to late stages of flowering in anthers, ovaries, and the tips of siliques (Fig. 3C,D). GUS analysis of the TSPO promoter confirmed that TSPO expression is significantly up-regulated in roots and shoots beginning at day 3 of a drought stress treatment. Up to the 5th day of the drought stress treatment, GUS staining was evident in young leaves and also surrounding the vascular tissue (Fig. 4A–D). GUS expression was visible in all leaves by the 7th day of the drought stress treatment. GUS localization was also observed in root tissue, however, the GUS staining was weak in relative comparison to the staining in shoot tissue (Fig. 4C–E). These results demonstrated that the TSPO promoter is a good candidate to regulate the gene expression in a drought-specific manner.

Analysis of TSPO and PDC1 promoter driven GUS expression. (A–E) TSPO promoter driven GUS expression in plants grown in ceramic-based granular soil at (A) 0, (B) 1, (C) 3, (D) 5, and (E) 7 days after the initiation of the drought stress treatment. Plants were grown in a ceramic-based granular soil. (F,G) PDC1 promoter of GUS expression in non-stressed and drought stressed plants grown on MS. (F) non-stressed, control plants (G) plants removed from the MS medium and subjected to 2 h of exposure to dry air in a laminar airflow cabinet.

GUS localization driven by the PDC1 promoter was not observed in ten days-old plants growing on MS medium. In contrast, however, strong GUS localization was observed in roots and shoots two hours after plants were subjected to a dry air treatment by uprooting the plants and placing them in a laminar flow cabinet. These data indicate that the expression of PDC1 is readily induced by drought stress (Fig. 4F,G).

Localization of PDC1:GFP

In silico analysis indicated that PDC1 localizes to the cytoplasm, however, its localization has not been verified. Therefore, to confirm its localization, four independent transgenic lines expressing PDC1 fused to GFP under the control of 1.9 kb PDC1 promoter sequence were analyzed. Results confirmed that PDC1 localizes to the cytoplasm of Arabidopsis root cells (Fig. 5A–F). As shown in Table 1, ALDH2B7 is reported to localize to mitochondria12. These data suggest that PDC1 converts pyruvate into acetaldehyde in the cytoplasm, which may then be transferred to mitochondria where acetaldehyde is converted to acetate by ALDH2B7.

TSPO promoter driven expression of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 in transgenic plants

To characterize the effect of the TSPO promoter in planta, a total of nine pTSPO-PDC1 and seven pTSPO-ALDH2B7 homozygous transgenic lines were developed. Initial evaluation of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 expression driven by the TSPO promoter, and drought tolerance in the transgenic lines, reduced the number to five pTSPO-ALDH2B7 and four pTSPO-PDC1 lines (Data not shown). Under normal growth conditions, the expression of TSPO is very low and the expression of both PDC1 and ALDH2B7 driven by the TSPO promoter was also low under normal growth conditions (Fig. 6A,B). After analyzing expression under normal growth conditions, the transgenic lines were subsequently grown in ceramic granular soil and subjected to a simulated drought stress. RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that the expression of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 in the transgenic lines was specifically up-regulated by drought stress, relative to their expression in WT plants (Fig. 6).

Confirmation of PDC1 or ALDH2B7 expression in transgenic lines of Arabidopsis. (A,B) Expression of ALDH2B7 in transgenic lines (A) root and (B) shoots. (C–D) Expression of PDC1 in transgenic lines (C) root and (D) shoots. An asterisk above a column indicates that the value is significantly different from WT plants based on a t-test (p < 0.05). n = 3.

In pTSPO-ALDH2B7-2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 transgenic lines, ALDH2B7 expression in roots and shoots of lines was comparable to WT plants under normal, non-stress conditions. In contrast, the expression of ALDH2B7 was significantly higher in the roots and shoots of these lines, relative to their expression in WT plants, seven days after the plants were subjected to drought stress (Fig. 6A,B). These results demonstrate that the TSPO promoter can be effectively used to regulate gene expression in a drought-specific manner.

The expression of PDC1 was also significantly higher in pTSPO-PDC1 transgenic lines (pTSPO-PDC1-3, pTSPO-PDC1-5, pTSPO-PDC1-8, pTSPO-PDC1-9), relative to WT plants, in response to drought stress. In these lines, the expression of PDC1 in roots was also higher in transgenic plants compared to the expression of these genes in WT plants; even under non-stress conditions (Fig. 6C).

pTSPO-PDC1 or pTSPO-ALDH2B7 transgenic plants exhibit higher survival ratio under drought stress conditions

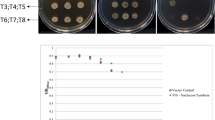

Different homozygous transgenic lines harboring pTSPO-PDC1 or pTSPO-ALDH2B7 were selected and subjected to a drought stress treatment. Three transgenic lines (pTSPO-ALDH2B7-4, pTSPO-ALDH2B7-6, and pTSPO-ALDH2B7-7) expressing ALDH2B7 under the control of the TSPO promoter exhibited a significantly higher survival ratio, relative to WT plants, in response to the drought stress treatment (Fig. 7A,B). Similarly, transgenic lines expressing pTSPO-PDC1 under control of the TSPO promoter also exhibited significantly higher survival ratio, relative to WT plants, under drought stress treatment (Fig. 7C,D). Importantly, no significant phenotypic changes, other than higher survival ratio under drought stress conditions, were observed in transgenic plants. The fresh weight of roots and shoots of plants expressing PDC1 or ALDH2B7 was comparable to WT plants when grown in ceramics granular soil (Fig. S3).

pTSPO-ALDH2B7 or pTSPO-PDC1 transgenic lines exhibit improved survival ratio under drought stress. (A) Survival ratio of pTSPO-ALDH2B7 lines. (B) WT and transgenic plants were re-watered after exposure to 15 days of drought stress (water withheld). (C) Survival ratio of pTSPO-PDC1 lines. (D) WT and transgenic plants were re-watered after exposure to 15 days of drought stress (water withheld). An asterisk above a column indicates that the value is significantly different from WT plants based on a t-test (p < 0.05). n = 4.

Microarray Analysis

Microarray analysis was performed to reveal the transcriptomic changes in pTSPO-PDC1 plants under control and drought stress conditions compared to WT plants. In WT plants, a total of 745 genes were significantly up-regulated in response to drought stress; among which, 499 genes were also up-regulated in pTSPO-PDC1 (Fig. 8A). A total of 795 genes were down-regulated in WT plants under drought stress; among which, 673 were also down-regulated in pTSPO-PDC1 plants under drought stress conditions (Fig. 8B). In pTSPO-PDC1 plants grown under control conditions, 171 genes were significantly up-regulated compared to WT plants grown under similar conditions. Among these, 78 genes were also up-regulated in WT plants under drought stress conditions (Table S1). Heatmap analysis highlights the expression changes in WT and transgenic plants under control and drought stress conditions (Fig. 8C,D). A total of 63 genes were up-regulated in pTSPO-PDC1 plants compared to WT plants under drought stress. In comparison to WT plants, the expression of PDC1 was higher in pTSPO-PDC1 plants under control and drought stress conditions (Table 2). These also included several genes that are involved in signaling (Such as ERF71) and are related to alternate respiratory pathways (such as NDB3 and NDB4). The expression of the Cox19-like CHCH family protein (AT5G09570), which is involved in positively regulating mitochondrial reactive oxygen response, was also significantly up-regulated22. Microarray analysis showed that ADH1 and ALDH2B7 expression levels are not up-regulated in pTSPO-PDC1 plants in either control or drought stress conditions. These results were further confirmed through RT-qPCR analysis (Fig. 9). Mapman analysis indicated that the TCA cycle is regulated in pTSPO-PDC1 lines to increase energy use efficiency under both control and drought stress conditions (Figs S4,S5). Gene ontology (GO) analysis also indicated that the expression of several catabolism related genes is altered in pTSPO-PDC1-5 plants under control as well as drought stress conditions (Figs S4,S5). Although there is no clear direction for these metabolic changes, it seems that additional acetic acid could also be used as an energy source to conserve cellular energy. As a result, this would provide transgenic plants with an advantage during drought stress conditions.

Summary of transcriptomic changes in WT and pTSPO-PDC1-5 in response to drought stress. (A,B) Venn diagram summarizing the number of genes up- (A) or down-regulated (B) in response to drought stress. (C,D) Heat map analysis of genes with at least two-fold increase or decrease in expression in pTSPO-PDC1-5 (P-5) plants compared to WT plants. (C) Genes differentially expressed in P-5 compared to WT plants when grown under well-watered conditions. (D) Genes differentially expressed in P-5 compared to WT plants when grown under drought stress conditions. (n = 3, FDR < 0.05, fold change > 2).

Confirmation of PDC1, ADH1 and ALDH2B7 expression in WT and pTSPO-PDC1 lines. Changes in the expression of PDC1 (A), ADH1 (B) and ALDH2B7 (C) in WT and pTSPO-PDC1 lines. Shoot samples were collected 11 days after drought stress treatment and plants that were maintained under watered conditions were used as controls. An asterisk above a column indicates that the value is significantly different from WT plants based on a t-test (p < 0.05). n = 3.

Discussion

Drought is a serious agricultural problem, and therefore, the development of drought tolerant plants is a very important technology that would allow us to better ensure our ability to meet the increasing demand of food as the population of the world increases1. Several strategies have been used to engineer transgenic plants that can tolerate low water availability, including the overexpression of late-embryogenesis-abundant (LEA) proteins, osmolyte biosynthesis genes, transcription factors and kinases, and ABA-signaling related genes. All of these approaches have resulted in the creation of transgenic plants with varying levels of increased drought tolerance1,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Transgenic maize lines have been tested in field conditions where they offered several advantages compared to WT plants under water limiting conditions30,31,32. In this regard, the molecular breeding of drought tolerant crops that utilize improved strategies could potentially alleviate the adverse effects of overexpressing specific genes to improve drought tolerance. The use of a suitable promoter to regulate the expression of genes that contribute to drought tolerance is essential in order to avoid any undesirable impacts on plant growth and yield16. Since roots sense water scarcity much earlier than shoots, an ideal promoter would first up-regulate target genes in roots and specifically during the early phase of drought stress.

In the present study, in order to identify a suitable promoter3, previously generated microarray data were used to analyze changes in the expression of genes in roots and shoots in soil-grown plants subjected to a drought stress. The analysis indicated that the Arabidopsis TSPO gene exhibited a basal, low-level of expression under non-stress conditions and was significantly up-regulated in roots and shoots during the early phase of drought stress (Table 1). RT-qPCR analysis further confirmed the expression pattern of TSPO in Arabidopsis roots and shoots. Promoter-GUS analysis also demonstrated that TSPO expression is very low under normal growth conditions. During the very early stage of drought stress response, TPSO is up-regulated and increases in expression as drought stress progresses. In Arabidopsis, TSPO has been reported to bind to the plasma membrane aquaporin (PIP2;7), as well as endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi membranes where it regulates the cell-surface expression of PIP2;7 under abiotic stress conditions20. The strict up-regulation of TSPO by ABA treatment21 and drought stress suggested that the TSPO promoter would be a good candidate to regulate the expression of transgenes in a drought responsive manner. The acetic acid pathway genes, PDC1 and ALDH2B7, were then selected and placed under the control of the TSPO promoter to determine if they would enhance drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants in a controlled manner.

PDC and ALDH family members play a functional role in the biosynthesis of acetic acid in plants7. The PDC gene family is confined to plants and fungi, while the ALDH family is ubiquitous in yeast, plants, and animals11,33,34,35. PDC1 transcripts comprise approximately 10–40% of the total PDC mRNA in seedlings under normal growth conditions, while this proportion reaches up to 99% under oxygen limiting conditions9. ABA and mannitol treatments also up-regulate the expression of PDC1 and ALDH2B79. Indeed the whole ethanol-acetic acid pathway is up-regulated by oxygen limiting conditions and ABA treatment, as well as under drought stress conditions3,9,36. PDC1 is expressed more highly in siliques and seeds9. In plants, members of ALDH2 family detoxify acetaldehyde generated during ethanol fermentation by converting it to acetate8,11,37. Acetate is further converted to acetyl-CoA via acetyl-CoA synthase activity. In Arabidopsis, 14 members of ALDH family have been described12 (Table 1 & Fig. S1). ALDH2B7 is phylogenetically related to ALDH2B4 and ALDH2C4 (Fig. S1). Characterization of mutants of the Arabidopsis ALDH family have revealed functions associated to drought stress. In the aldh2B7 mutant, the conversion of ethanol to fatty acids is not affected, while conversion is significantly decreased in the aldh2B4 single and aldh2B4/aldh2B7 double mutants. Thus, under normal growth conditions, ALDH2B4 has been suggested to play a dominant role in the PDH bypass pathway8. The expression of ALDH2B7 in response to drought stress is up-regulated much earlier than ALDH2B4 (Table 1), suggesting that the role of ALDH2B7 in the response to drought stress may be more critical than ALDH2B4.

Similarly, among the Arabidopsis PDC members, the expression of PDC1 is more highly up-regulated by drought stress than PDC2, PDC3, and PDC4 (Table 1). The expression of PDC1 was observed during different developmental stages of Arabidopsis (Fig. S6). As previously mentioned, Arabidopsis PDC1 and ALDH2B7 genes are involved in the acetic acid fermentation pathway (Fig. 1) and the expression of ALDH2B7 is up-regulated in response to ABA application and osmotic stress. Similar to PDC1, the expression of ALDH2B7 was also observed during different developmental stages of Arabidopsis (Fig. S7). The current study confirmed that the expression of ALDH2B7 is up-regulated in both roots and shoots by drought stress. A previous study suggested that ALDH may play a role in the aerobic detoxification of acetaldehyde and that ALDH activity during stress might occur independently of ethanol fermentation9. The role of Arabidopsis PDC genes in ethanol fermentation has also been previously described10, however, its role in the production of acetate through the PDH independent pathway has not been described in detail. The collective analysis of the published data clearly indicates that these genes could play an important role in drought stress response through a PDH independent pathway. It is plausible that the continuous production of acetic acid could have a negative impact on plant growth. This was experimentally verified in the current study by watering two-week-old Arabidopsis plants once a week for five weeks with 10 mM acetic acid. Plants treated with acetic acid were dwarfed and produced less biomass relative to control plants (Fig. S8). These results indicated that selecting a suitable promoter, such as the TSPO promoter, would be extremely important to the development of drought stress tolerant plants while avoiding any undesirable effects on growth and yield. Microarray data also suggested that plants expressing ALDH2B7 and PDC1 under the control of the TSPO promoter could provide significant tolerance to drought stress. Therefore, transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing either PDC1 or ALDH2B7 under the control of the drought stress-inducible TSPO promoter were developed to test this hypothesis.

A total of 7 and 9 homozygous transgenic lines were developed for pTSPO-PDC1 and pTSPO-ALDH2B7, respectively. RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that the level of expression of PDC1and ALDH2B7 under normal growth conditions was comparable to WT plants. In addition, in relative comparison to WT plants, the expression of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 in the transgenic plants was specifically up-regulated by drought stress. Three independent transgenic lines of pTSPO-ALDH2B7 and four lines harboring pTSPO-PDC1 exhibited significantly higher survival ratio under drought stress. These results confirmed our hypothesis that the regulation of acetic acid biosynthesis pathway genes could significantly enhance survival ability of plants under drought stress. Since the modulation of the acetic acid pathway via the constitutive overexpression of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 could negatively impact plant growth, the use of the TPSO promoter, which is specifically regulated by drought stress, can minimize off-types by driving expression only during periods of stress exposure. Regulating drought stress tolerance by modulating the expression of acetic acid pathway genes is a unique strategy. Although transgenic plants expressing pTSPO-ALDH2B7 or pTSPO-PDC1 have not been previously evaluated for drought stress tolerance, plants expressing PDC or ALDH family members have been tested for their response to other abiotic stresses8,9,10,15,38,39. PDC1, which is localized in the cytoplasm, converts pyruvate into acetaldehyde which may then be transferred to mitochondria where it is converted to acetate by ALDH2B7 in a well-coordinated manner. The development and analysis of transgenic plants exhibiting improved survival ratio under drought stress by modulating the expression of acetic acid pathway genes increases our understanding of the mechanisms responsible for drought stress tolerance in plants and also provides an opportunity to use this approach to ameliorate the injury caused by drought stress in field-grown crops. In a previous study, treatment of plants with acetic acid did not confer any undesirable phenotype in roots and shoots5. Similarly, the transgenic plants generated in the present study also did not exhibit any undesirable phenotypes. As a result, these observations confirm that the TSPO promoter is a good tool that can be used to regulate the expression of genes in a drought-responsive manner.

It is possible that the PDH bypass contributes to maintaining an optimal metabolic rate when plants are subjected to abiotic stresses and therefore minimizes the deleterious impact that abiotic stress has on plants. Acetyl-CoA plays a role in fatty acid metabolism. Exogenous application of labelled acetate and ethanol are readily incorporated into fatty acids and approximately 90% of this incorporation relies on the activity of the ACS enzyme7. Specific plant tissues, such as floral tissues, have been reported to undergo aerobic fermentation37,40,41,42, where pyruvate is converted to ethanol or acetate7. Subsequently, ACS converts the acetate to acetyl-CoA for use in fatty acid biosynthesis (Fig. 1). The importance of this pathway during flowering has been reported, however, it is not clear if acetate is processed in the same manner during drought stress. Importantly, the expression of ADH is significantly up-regulated by drought stress; however, the expression of mitochondrial components of PDH are significantly down-regulated (Fig. 1) by drought stress3. These observations indicate that the role of the PDH bypass pathway during drought response is extremely important for the synthesis of acetic acid, as well as acetyl-CoA. In addition to participating in fatty acid metabolism as part of a stress response7,43, the acetate produced by the enhanced expression of PDC1 or ALDH2B7 could also participate in histone acetylation, where the acetyl functional group of acetyl-CoA is transferred to histone44. Histone acetylation is an important aspect of the epigenetic regulation of gene expression in eukaryotes. In this process, acetyl-CoA acts as a metabolic signal regulating plant response to various abiotic stresses, as well as normal growth, through epigenetic changes involving histone acetylation44,45,46,47. Acetic acid enhances drought stress tolerance through jasmonate synthesis and enrichment of histone H4 acetylation; and by contributing to the induction of the jasmonate signaling pathway5. Acetic acid activates the COI1-mediated signaling pathway and the transient production of JA may define which downstream target genes are activated5 to enhance drought tolerance.

Microarray analysis revealed the up- and down-regulation of several genes related to primary and secondary metabolism (Figs S4 and S5). The expression of ADH1 is not significantly altered, which indicates that ethanol synthesis may not be related to drought stress tolerance in pTSPO-PDC1 lines. Although the expression of ALDH2B7 is also not significantly up-regulated in pTSPO-PDC1, the overlapping phenotype of pTSPO-PDC1 and pTSPO-ALDH2B7, as well as the exhibition of drought tolerance by the external application of acetic acid, supports the claim that acetic acid could increase drought stress tolerance in plants. Several signaling related genes, such as ERF71, were also up-regulated in pTSPO-PDC1 plants compared to WT plants. ERF71 mediates osmotic and hypoxia stress response in Arabidopsis48. In Arabidopsis, NAD(P)H dehydrogenases are located on both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane as part of the non-phosphorylating alternative pathway and play important roles in the development of the plant and its ability to cope with oxidative stress49. The expression of two members of NAD(P)H dehydrogenases (NDB3, NDB4) which face the intermembrane space50 was significantly up-regulated in pTSPO-PDC1 plants compared to WT plants, which suggests that transgenic plants are using alternative respiratory pathways. The changes in expression of other genes (Table 2, Table S1 & Figs S4 and 5) also suggest that pTSPO-PDC1 plants might be selectively regulating the metabolism using alternate energy pathways to conserve energy which gives them an advantage under drought stress conditions. GO analysis also highlights that the expression of several metabolic related genes was significantly altered in pTSPO-PDC1 compared to WT plants. Thus, in transgenic plants, in addition to JA signaling, metabolism is also regulated; which may help to conserve energy and thus provide an advantage to confer drought stress tolerance. It should be noted, however, that acetic acid mediated drought stress tolerance is a novel mechanism and further studies (such as NMR analysis) are needed to decide the fate of acetic acid in this energy conservation pathway.

In summary, the analysis of previously-generated microarray data resulted in the identification of the TSPO promoter that can be used to specifically up-regulate genes in both roots and shoots starting in the early phase of the response to drought stress. Transgenic plants expressing the acetic acid biosynthesis pathway genes, PDC1 or ALDH2B7, under the control of the TSPO promoter exhibited phenotypes with enhanced survival ratio under drought stress conditions. These results demonstrate that modulating the acetic acid biosynthesis pathway can be a useful strategy for the development of plants with the ability to survive longer under drought stress conditions. In current studies, we have developed and analyzed Arabidopsis plants which exhibit ability to survive under drought stress conditions. Since external application of acetic acid has been shown to confer drought stress tolerance in rapeseed, maize, rice and wheat plants in addition to Arabidopsis5, it is reasonable to propose that this transgenic technology may also be effective in other crop plants.

Materials and Methods

Development of transgenic lines

A 1.4-kb region upstream of the ATG start site of the TSPO gene in Arabidopsis was cloned using the forward and reverse primers, 5′-ATAGTAGACTGCGGCCGCACCATGGCA-3′ and 5′-TGTCCTGAGATCTAGATACAAACGAAACGTCCAAAAC-3′. A NotI site was introduced into the forward primer, and a XbaI site was introduced into the reverse primer. The obtained TSPO promoter was then cloned into the pGreenII 0029 and pGreenII 0229 vectors. ALDH2B7 and PDC1 genes were cloned downstream of the TSPO promoter in the pGreenII 0229 and the pGreenII 0029 vectors, respectively. The primers used for the cloning of PDC1 were 5′-CTCGAATTCCCCGGGTTAATTAAATTAATC-3′ and 5′-ATCAGGCCGTCGACGCCGGATC-3′ with introduced SmaI and SalI sites, respectively. The primers used for the cloning of ALDH2B7 were 5′-AATCGGCCCCCGGGTTAATTAAATTAATC -3′and 5′-TGGAGCTAGTCGACTTATGGCCGA-3′ and also contained introduced SmaI and SalI sites, respectively. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing either pTSPO-ALDH2B7 or pTSPO-PDC1 were created using Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101::pMP90)-mediated transformation and the floral dip method51. Neomycin phosphotransferase II (NPT II) and the bialaphos resistance gene (bar) were part of the generated constructs and used to select for transformed plants using kanamycin (km) and bialaphos for pTSPO-PDC1 and pTSPO-ALDH2B7, respectively.

In order to conduct a GUS analysis of the PDC1 promoter, a 1.9 kb region upstream of the PDC1 gene was amplified using the primers, 5′-CACCGACGCACTTTATTGTGTTGCAA-3′ and 5′-GGAAATGGGAAGGTTTGAGTTC-3′. The PCR product was cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen) vector. After sequence confirmation, the PDC1 promoter was subcloned into pMDC163 and expressed as the construct PDC1p::uidA. A similar approach was used for the GFP analysis, with an exception. Specifically, after sequence confirmation, the promoter construct was cloned into pMDC111 where it was used to drive expression of the GFP gene. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing either the PDC1 promoter fused to the GUS gene or the PDC1 promoter fused to the GFP gene were created using Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101)-mediated transformation with the floral dip method51. The vectors used for transformation are illustrated in Fig. S2D–H.

The gene sequences for TSPO, PDC1, and ALDH2B7 (Fig. S2A–C) were acquired from the TAIR website (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). The hygromycin phosphotransferase gene was included in the construct that was used to transform Arabidopsis plants with PDC1p::uidA, and PDC1p:PDC1::GFP and Hygromycin B was used to select successfully transformed plants. Homozygous transgenic lines were developed and used in the subsequent experiments.

Drought stress treatment

WT and transgenic seeds were sown in trays containing Dio propagation mix no. 2 professional soil (Dio Chemicals, Japan) and germinated and grown at 22 °C under a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle, and a ~100 µmol m−2 s−1 photon flux density. Two weeks after germination, plants were subjected to drought treatment by removing excess water from the trays and ceasing any subsequent watering. For microarray analyses, shoot samples were collected 11 days after drought stress treatment and plants that were maintained under watered conditions were used as controls. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 degrees until RNA extraction. Drought tests were performed with four replications and were repeated at least two times. Each replication consisted of 24 individual plants for WT and each transgenic line. In cases where the plants were grown in ceramic-based granular soil, the drought stress was applied as previously described3. Briefly, plants were grown on MS medium for 10 days at 22 °C and subsequently transferred to ceramic-based granular soil (size 2.5 L, Sakatanotane, Japan). After transfer to this substrate, plants were grown for an additional 7 days at 22 °C. The drought treatment was then administered by removing excess water from the trays and ceasing any subsequent watering. The survival ratio of WT and transgenic plants was calculated by counting the number of plants that survived at 24 and 48 hours after re-watering, relative to the initial number of total plants subjected to the drought treatment. Plants were harvested at 0 and 7 days after onset of the drought treatment and root and shoot fresh weights were measured.

RT-qPCR analysis

Plants from lines that were homozygous for the pTSPO-ALDH2B7 or pTSPO-PDC1 genes were developed and drought-inducible expression was confirmed by RT-qPCR for the ALDH2B7, PDC1, and TSPO genes. cDNA from each sample was synthesized from 200 ng of extracted RNA using a QuantiTect Reverse transcription kit (QIAGEN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The forward and reverse primers used for PDC1 were 5′-AGAGCACCATCCTCATTTCATT-3′ and 5′-TGGCTTTTTCTTTCTTGAGGAG-3′, respectively. The forward and reverse primers used for ALDH2B7 were 5′-CATGCTCATAGCAACAGACGA-3′ and 5′-CAGCAGCTAAACCGTACCTTG-3′, respectively. The forward and reverse primers used for TSPO were 5′-CTCAGTTTTTGCTCTGTTTGGTT-3′ and 5′-CAAACACGGCTTTACCAGATTAC-3′, respectively. For ADH1, the forward and reverse primers were 5′-AGACGATGCCTTCAAGACTCA-3′ and 5′-GGGAATGTCAGTTTTGGGTTT-3′, respectively. Actin 2 was used as an internal control and amplified using the forward and reverse primers, 5′-TGAAGTGTGATGTGGATATCAGG-3′ and 5′-GATTTCTTTGCTCATACGGTCAG-3′, respectively. Changes in expression were recorded according to the standard curve method.

Microarray analysis

Microarray analyses were carried out as described previously3 with few modifications. Total RNA (400 ng) was labeled with fluorescently-labeled Cy3, using a Quick Amp labeling kit (Agilent Technologies) and resulting cRNA was subsequently hybridized to an Agilent Arabidopsis custom microarray (GPL19830). Microarray analyses were performed with three biological replications. Arrays were scanned with a microarray scanner (G2505B, Agilent Technologies) and microarray data were processed and analyzed using GeneSpring GX (v.14.9, Agilent Technologies) with quantile normalization and median transformation. Statistical significance was assessed using a one way ANOVA with BH correction52 and a 95% confidence interval (Corrected P-value < 0.05). A Tukey’s HSD (honest significant difference) test with BH correction was performed as a post hoc test (Corrected P-value < 0.05). Genes with false discovery rate (FDR) values less than 0.05 and at least two-fold changes were regarded as up- or down-regulated. Heat map analyses were performed with an online tool heatmapper53. The normalized log2 values were then used to compare the transcriptomic changes using MapMan 3.6.0RC154. Gene ontology analyses were carried out using the PANTHER (protein annotation through evolutionary relationship) classification system database maintained at http://pantherdb.org/ 55. The microarray data has been deposited to GenBank with the accession number GSE110857.

TSPO and PDC1 promoter driven GUS analysis

Transgenic plants derived from five homozygous lines of plants transformed with the GUS gene driven by the TSPO or PDC1 promoter were used to analyze β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining. Plants used to evaluate TSPO driven GUS expression were grown in ceramic-based granular soil and samples were collected at 0, 1, 3, 5 and 7 days after the application of the drought treatment as previously described. GUS expression was observed in four independent transgenic lines. Plants used to analyze PDC1 promoter activity were grown on MS medium for 10 days and samples were collected at 0 and 2 h after a drought treatment was administered. The drought treatment was initiated by pulling plants from MS medium and placing them in a petri dish which was subjected to the airflow of a laminar hood. The GUS analysis was conducted by dipping the plants twice in phosphoric acid buffer and then incubating them overnight in 0.5 mM X-Gluc (10 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM phosphoric acid buffer (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 2% DMSO) at 37 °C. The solution was then replaced with serial dilutions of ethanol and the samples were subsequently stored in 100% ethanol until they were photographed.

Confirmation of the subcellular localization of PDC1

The cellular localization of PDC1, PDC2, PDC3 and PDC4 was predicted in silico using SUBA (Arabidopsis Subcellular Database) which is maintained at www.suba3.plantenergy.uwa.edu.au. The subcellular localization of PDC1 was also verified experimentally. Four independent homozygous lines of pPDC1:PDC1::GFP were examined in order to observe GFP localization in Arabidopsis roots using a LSM700 Laser scanning microscope with a 40 × Plan-Apochromat lens. A diode laser with a 488 nm excitation in conjunction with 488–555 nm and 560–700 nm) filters were used to observe the fluorescence of GFP. The obtained data were analyzed using ZEN 2011 software (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany).

Phylogenetic Analysis

Protein sequences were acquired from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) database and aligned by ClustalW in a CLC sequence viewer 8.0 (QIAGEN, Denmark). Subsequently, a phylogeny was constructed using a neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm with the Jukes-Cantor distance measurement method56,57. The bootstrap analysis was carried out for the branching arrangements with 1000 replicates58.

References

Todaka, D., Shinozaki, K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Recent advances in the dissection of drought-stress regulatory networks and strategies for development of drought-tolerant transgenic rice plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00084 (2015).

Yoshida, T., Mogami, J. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-dependent and ABA-independent signaling in response to osmotic stress in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 21, 133–139 (2014).

Rasheed, S., Bashir, K., Matsui, A., Tanaka, M. & Seki, M. Transcriptomic analysis of soil-grown Arabidopsis thaliana roots and shoots in response to a drought stress. Frontiers in Plant Science 7, 180, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00180 (2016).

Rasheed, S. et al. Drought stress differentially regulates the expression of small open reading frames (sORFs) in Arabidopsis roots and shoots. Plant Signaling & Behavior 11, e1215792, https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2016.1215792 (2016).

Kim, J.-M. et al. Acetate-mediated novel survival strategy against drought in plants. Nature Plants 3, 17097, https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2017.97 (2017).

To, T. K. et al. Arabidopsis HDA6 regulates locus-directed heterochromatin silencing in cooperation with MET1. PLoS Genetics 7, e1002055 (2011).

Lin, M. & Oliver, D. J. The role of acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 147, 1822–1829 (2008).

Wei, Y., Lin, M., Oliver, D. J. & Schnable, P. S. The roles of aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs) in the PDH bypass of Arabidopsis. BMC Biochemistry 10, 7 (2009).

Kürsteiner, O., Dupuis, I. & Kuhlemeier, C. The pyruvatedecarboxylase1 gene of Arabidopsis is required during anoxia but not other environmental stresses. Plant Physiology 132, 968–978 (2003).

Mithran, M., Paparelli, E., Novi, G., Perata, P. & Loreti, E. Analysis of the role of the pyruvate decarboxylase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana under low-oxygen conditions. Plant Biology 16, 28–34, https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12005 (2014).

Brocker, C. et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) superfamily in plants: gene nomenclature and comparative genomics. Planta 237, 189–210 (2013).

Stiti, N., Missihoun, T. D., Kotchoni, S. O., Kirch, H.-H. & Bartels, D. Aldehyde dehydrogenases in Arabidopsis thaliana: biochemical requirements, metabolic pathways, and functional analysis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2, 65, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2011.00065 (2011).

Zarei, A., Trobacher, C. P. & Shelp, B. J. Arabidopsis aldehyde dehydrogenase 10 family members confer salt tolerance through putrescine-derived 4-aminobutyrate (GABA) production. Scientific Reports 6, 35115, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35115 (2016).

Kirch, H.-H., Schlingensiepen, S., Kotchoni, S., Sunkar, R. & Bartels, D. Detailed expression analysis of selected genes of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Molecular Biology 57, 315–332 (2005).

Kotchoni, S. O., Kuhns, C., Ditzer, A., Kirch, H. H. & Bartels, D. Over-expression of different aldehyde dehydrogenase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana confers tolerance to abiotic stress and protects plants against lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. Plant, Cell & Environment 29, 1033–1048 (2006).

Nakashima, K. et al. Comparative functional analysis of six drought-responsive promoters in transgenic rice. Planta 239, 47–60, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-013-1960-7 (2014).

Kasuga, M., Liu, Q., Miura, S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. Improving plant drought, salt, and freezing tolerance by gene transfer of a single stress-inducible transcription factor. Nature Biotechnology 17, 287–291, https://doi.org/10.1038/7036 (1999).

Batoko, H., Jurkiewicz, P. & Veljanovski, V. Translocator proteins, porphyrins and abiotic stress: new light? Trends Plant Science 20, 261–263, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2015.03.009 (2015).

Guillaumot, D., Guillon, S., Morsomme, P. & Batoko, H. ABA, porphyrins and plant TSPO-related protein. Plant Signaling & Behavior 4, 1087–1090 (2009).

Hachez, C. et al. The Arabidopsis abiotic stress-induced TSPO-Related protein reduces cell-surface expression of the aquaporin PIP2;7 through protein-protein interactions and autophagic degradation. Plant Cell 26, 4974–4990, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.114.134080 (2014).

Guillaumot, D. et al. The Arabidopsis TSPO-related protein is a stress and abscisic acid-regulated, endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi-localized membrane protein. Plant Journal 60, 242–256 (2009).

Liang, M. et al. Subcellular distribution of NTL transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Traffic 16, 1062–1074 (2015).

Baldoni, E., Genga, A. & Cominelli, E. Plant MYB transcription factors: Their role in drought response mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, 15811–15851, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160715811 (2015).

Harb, A., Krishnan, A., Ambavaram, M. M. & Pereira, A. Molecular and physiological analysis of drought stress in Arabidopsis reveals early responses leading to acclimation in plant growth. Plant Physiology 154, 1254–1271, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.110.161752 (2010).

Iuchi, S. et al. Regulation of drought tolerance by gene manipulation of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, a key enzyme in abscisic acid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Journal 27, 325–333, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01096.x (2001).

Karakas, B., Ozias-Akins, P., Stushnoff, C., Suefferheld, M. & Rieger, M. Salinity and drought tolerance of mannitol-accumulating transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell & Environment 20, 609–616, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.1997.00132.x (1997).

Kuromori, T. et al. Overexpression of AtABCG25 enhances the abscisic acid signal in guard cells and improves plant water use efficiency. Plant Science, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.02.019 (2016).

Park, M. Y., Kang, J.-y. & Kim, S. Y. Overexpression of AtMYB52 confers ABA hypersensitivity and drought tolerance. Molecules & Cells 31, 447–454, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10059-011-0300-7 (2011).

Umezawa, T., Fujita, M., Fujita, Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. Engineering drought tolerance in plants: discovering and tailoring genes to unlock the future. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 17, 113–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2006.02.002 (2006).

Castiglioni, P. et al. Bacterial RNA chaperones confer abiotic stress tolerance in plants and improved grain yield in maize under water-limited conditions. Plant Physiology 147, 446–455 (2008).

Nemali, K. S. et al. Physiological responses related to increased grain yield under drought in the first biotechnology‐derived drought‐tolerant maize. Plant, Cell & Environment 38, 1866–1880 (2015).

Nuccio, M. L. et al. Expression of trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase in maize ears improves yield in well-watered and drought conditions. Nature Biotechnology 33, 862 (2015).

Ismond, K. P., Dolferus, R., De Pauw, M., Dennis, E. S. & Good, A. G. Enhanced low oxygen survival in Arabidopsis through increased metabolic flux in the fermentative pathway. Plant Physiology 132, 1292–1302 (2003).

Jackson, B. et al. Update on the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH) superfamily. Human Genomics 5, 1 (2011).

Sophos, N. A. & Vasiliou, V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase gene superfamily: the 2002 update. Chemico-Biological Interactions 143, 5–22 (2003).

Papdi, C. et al. The low oxygen, oxidative and osmotic stress responses synergistically act through the ethylene response factor VII genes RAP2. 12, RAP2. 2 and RAP2. 3. Plant Journal 82, 772–784 (2015).

op den Camp, R. G. & Kuhlemeier, C. Aldehyde dehydrogenase in tobacco pollen. Plant molecular biology 35, 355–365 (1997).

Huang, W. et al. Significant improvement of stress tolerance in tobacco plants by overexpressing a stress-responsive aldehyde dehydrogenase gene from maize (Zea mays). Plant Molecular Biology 68, 451–463 (2008).

Sunkar, R., Bartels, D. & Kirch, H.-H. Overexpression of a stress-inducible aldehyde dehydrogenase gene from Arabidopsis thaliana in transgenic plants improves stress tolerance. Plant Journal 35, 452–464 (2003).

Gass, N. et al. Pyruvate decarboxylase provides growing pollen tubes with a competitive advantage in petunia. Plant Cell 17, 2355–2368 (2005).

Mellema, S. et al. The ethanolic fermentation pathway supports respiration and lipid biosynthesis in tobacco pollen. Plant Journal 30, 329–336 (2002).

Tadege, M. & Kuhlemeier, C. Aerobic fermentation during tobacco pollen development. Plant Molecular Biology 35, 343–354 (1997).

Oliver, D. J., Nikolau, B. J. & Wurtele, E. S. Acetyl-CoA—Life at the metabolic nexus. Plant Science 176, 597–601, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.02.005 (2009).

Shen, Y., Wei, W. & Zhou, D.-X. Histone acetylation enzymes coordinate metabolism and gene expression. Trends in Plant Science 20, 614–621 (2015).

Kim, J.-M., Sasaki, T., Ueda, M., Sako, K. & Seki, M. Chromatin changes in response to drought, salinity, heat, and cold stresses in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 6, 114, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00114 (2015).

Sutendra, G. et al. A Nuclear pyruvate dehydrogenase complex is important for the generation of acetyl-CoA and histone acetylation. Cell 158, 84–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.046 (2014).

Chen, C. et al. Cytosolic acetyl-CoA promotes histone acetylation predominantly at H3K27 in Arabidopsis. Nature Plants. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-017-0023-7 (2017).

Park, H.-Y. et al. AtERF71/HRE2 transcription factor mediates osmotic stress response as well as hypoxia response in Arabidopsis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 414, 135–141 (2011).

Smith, C. et al. Alterations in the mitochondrial alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenase NDB4 lead to changes in mitochondrial electron transport chain composition, plant growth and response to oxidative stress. Plant and Cell Physiology 52, 1222–1237, https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcr073 (2011).

Carrie, C. et al. Type II NAD (P) H dehydrogenases are targeted to mitochondria and chloroplasts or peroxisomes in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Letters 582, 3073–3079 (2008).

Zhang, X., Henriques, R., Lin, S.-S., Niu, Q.-W. & Chua, N.-H. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nature Protocols 1, 641–646, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2006.97 (2006).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 57, 289–300, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.111.087866 (1995).

Babicki, S. et al. Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Research 44, W147–W153 (2016).

Thimm, O. et al. Mapman: a user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant Journal 37, 914–939, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02016.x (2004).

Mi, H., Muruganujan, A., Casagrande, J. T. & Thomas, P. D. Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nature Protocols 8, 1551–1566, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.092 (2013).

Jukes, T. H. & Cantor, C. R. In Mammalian protein metabolism Vol. 3 (ed Munro, H. N.) Ch. 24, 21–132 (Acedemic Press, 1969).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 4, 406–425 (1987).

Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791 (1985).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), Core Research for Evolutionary Science and Technology (CREST; JPMJCR13B4 to MS), grants from RIKEN, Japan [to MS] and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, (Innovative Areas 18H04791 and 18H04705 to MS). K.B. is supported through the RIKEN FPR program and S.R. is supported by the RIKEN JRA program. We are grateful to Junko Ishida, Dr. Kentaro Nakaminami and Dr. Akihiro Matsui (RIKEN CSRS) for supporting our experiments and useful discussions. We are also obliged to Dr. Kousuke Hanada to kindly provide data regarding the expression of PDC1 and ALDH2B7 in different plant parts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.K. and M.S. conceived the research. S.R., K.B. M.A. and M.T., conducted the experiments. S.R., K.B., J.M.K. and M.S. analyzed and discussed the data. K.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasheed, S., Bashir, K., Kim, JM. et al. The modulation of acetic acid pathway genes in Arabidopsis improves survival under drought stress. Sci Rep 8, 7831 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26103-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26103-2

This article is cited by

-

Modulation of antioxidant defense and PSII components by exogenously applied acetate mitigates salinity stress in Avena sativa

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Acetic acid: a cheap but chief metabolic regulator for abiotic stress tolerance in plants

Stress Biology (2024)

-

Acetic Acid Alleviates Salinity Damage and Improves Fruit Yield in Strawberry by Mediating Hormones and Antioxidant Activity

Erwerbs-Obstbau (2023)

-

Physio-biochemical Mechanisms of Acetic Acid Involved in Cold and Freezing Tolerance in Mexican Lime Plants (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle)

Erwerbs-Obstbau (2023)

-

Simple and universal function of acetic acid to overcome the drought crisis

Stress Biology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.