Abstract

The quick spread of the chestnut gall wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus in Europe constitutes an outstanding example of recent human-aided biological invasion with dramatic economic losses. We screened for the first time a set of five nuclear and mitochondrial genes from D. kuriphilus collected in the Iberian Peninsula, and compared the sequences with those available from the native and invasive range of the species. We found no genetic variability in Iberia in none of the five genes, moreover, the three genes compared with other European samples showed no variability either. We recorded four cytochrome b haplotypes in Europe; one was genuine mitochondrial DNA and the rest nuclear copies of mitDNA (numts), what stresses the need of careful in silico analyses. The numts formed a separate cluster in the gene tree and at least two of them might be orthologous, what suggests that the invasion might have started with more than one individual. Our results point at a low initial population size in Europe followed by a quick population growth. Future studies assessing the expansion of this pest should include a large number of sampling sites and use powerful nuclear markers (e. g. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) to detect genetic variability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global trade is increasing alien species introduction all over the world, many of which are agricultural pests favoured by a poor control of the movement of plant material1. The accidental introduction and spread of the oriental chestnut gall wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) in Europe constitutes one of the most spectacular invasions detected in recent times and has already provoked dramatic economic losses in Castanea sativa nut production2.

Dryocosmus kuriphilus was first detected in Italian chestnuts orchards in 2002, where infested plant material brought from China was introduced3,4. The pest has since then literally taken Europe by storm and can be currently found in more than a dozen European countries5. Females oviposit into the buds and larval development provokes the abnormal development of twigs and the formation of galls6. The galls hamper plant growth, alter floral development and provoke reductions in chestnut yields of up to 80%2,7.

The spread of D. kuriphilus out of Italy first reached nearby countries like France and Switzerland (2005 and 2009, respectively) and then Slovenia, Croatia or Austria; nowadays, the pest has already arrived at areas as far north as the Netherlands5. On the eastern margin, recent records confirm its presence in Turkey8 and in the west it was detected in 2012 in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula9. In Iberia, this gall wasp is now present in most chestnut forests and orchards, including the southernmost populations of this tree in Andalusia (Spain)10. The rapid spread of the pest has been favoured by the movement of infested material, as the eggs are difficult to detect within the dormant buds. Also, new populations may be founded by a single female and grow in number very quickly in this fecund thelytokous species (produces fertile eggs by parthenogenesis)11,12.

The extremely rapid expansion of the pest over Europe suggests multiple introductions by humans5, as it largely exceeds the dispersal rates estimated for this insect in 8 km/year13. Current efforts for the control of this pest rely on the introduction of a parasitoid native from the original distribution range of the pest in China, namely Torymus sinensis (Hymenoptera: Torymidae), which can reduce gall wasp numbers14. Nonetheless, in those areas where the pest does not occur, the most urgent measure consists in avoiding its arrival. In this sense, the use of molecular techniques allows detecting D. kuriphilus in infested plant material. DNA extraction from bud tissue before budburst, followed by a successful amplification of wasp genes, constitutes an undoubtable proof of the presence of wasp eggs15. Besides, genetic analyses may also inform about the origin of the invasive wasp populations, providing crucial information about pest dispersal aided by humans16.

The first molecular approach to assess the origin and spread of D. kuriphilus in Europe consisted in sequencing one mitochondrial gene (cytochrome oxidase I) from wasps in Slovenia, Croatia and western Italy5. The presence of a unique haplotype coincident with that recorded elsewhere in Italy17 and identical to the most widespread haplotype in China18, led them to propose that the invasion resulted from a single introduction from Asia and further expansion after a severe population bottleneck5. This article provides valuable information on the origin of the invasion and puts forward the invasive capability of this pest. However, when mutation rates differ across genes, as is the case in the fast-evolving hymenoptera mitochondrial genome19,20, sequencing more than one gene could show intra-specific genetic variability otherwise undetected.

In the present study, we sequenced and screened five genes (mitochondrial and nuclear) in an introduced population of the oriental chestnut gall wasp in Andalusia (southern Spain), far away from the origin of the invasion in Europe. Our specific objectives were: i) to analyse the intra-specific genetic variability of each gene among the Spanish samples ii) to compare the Iberian sequences with those available from Europe and Asia iii) to assess which of these genes could be suitable (i. e. variable enough) markers for future studies on the phylogeography and population genetics of the species.

Results

Only one haplotype was retrieved for each of the nuclear genes sequenced (28S and ITS2). The 28S (D3-D5 region) Iberian haplotype (Accession number MH116002) was identical to that obtained from a D. kuriphilus individual collected in Italy (Accession number DQ286819). In the case of ITS2, the Iberian haplotype (Accession number MH116003) showed no differences with those reported from Japan and Italy (Accession numbers AB200276 and JQ229194, respectively). No double peaks were detected at any site after a careful inspection of the chromatograms.

The sequence of cytochrome oxidase I (hereon cox1) was identical in the 24 individuals analysed (Accession number MH119939) and, at the same time, showed no differences with those previously reported from Italy and Slovenia (Accession numbers DQ286810 and KF308606) and with one of the haplotypes in China (JF411594). The cox1 gene tree built for Dryocosmus spp. and allied genera showed that D. kuriphilus constitutes a monophyletic clade (Fig. 1). Within this, D. kuriphilus sequences formed two clusters, one of them with wasps collected only within galls of Castanea henryi21. The Iberian haplotype was included in the other clade, which grouped sequences from individuals recorded on different species of Castanea (Fig. 1). All the sequences of the mitochondrial 16S (Accession number MH116001) were identical.

Cytocrome oxidase I gene tree for Dryocosmus spp. and allied genera (sequences available from Ács et al. (2007, ref.17). Tree topology was inferred using Bayesian inference with substitution models HKY+ Gamma for the first and third codon positions and F81+ inv for the second one. Support for each node is represented by the Bayesian probability value. Taxonomic identity of each sequence taken from GenBank, numbers besides scientific names indicate the accession numbers.

The case of cytochrome b (hereon cytb) deserves special attention: from the 24 Iberian wasp larvae we obtained two distinct haplotypes; the first one (hereon Iberia 1) was the most prevalent (Accession number MH119938), 18 individuals versus 6 that beared the haplotype Iberia 2 (Accession number MH119937). The two haplotypes were found in the three nearby sampling sites, and their relative prevalence did not differ among sites (Chisq = 0.33; df = 2; P = 0.84). According to the uncorrected genetic distance, the divergence between these two haplotypes was 12% (34 variable sites in a sequence 275 bp long) (Table 1a) and 13.2% applying the Kimura 2-parameter model (Table 1b). We repeated the PCRs and the sequencing to discard any potential error at any stage of the process. We confirmed that no error was made, the sequences were identical to the original and the same two distinct haplotypes were retrieved.

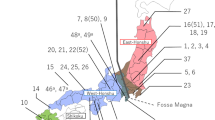

When we built the gene tree with all the cytb sequences available for Dryocosmus spp. (Fig. 2), we realised that such an extreme intra-specific divergence was not uncommon. From GenBank we downloaded three more sequences that corresponded to two highly divergent haplotypes: the first one was recorded in Italy (reference DQ286803) and the second in Italy and Hungary (references KU760838 and KU760839, respectively). They diverged more than 7% using either the uncorrected genetic distance or the K2P model (Table 1a and b). One of these haplotypes (DQ286803) clustered with Iberia 2 (from which it diverged in only one base located in the third codon position) (Table 1a and b; Fig. 2). Within the Dryocosmus spp. cytb gene tree these three haplotypes (four sequences) formed a monophyletic clade with a high node support (Fig. 2). By contrast, the haplotype Iberia 1 of D. kuriphilus grouped with Dryocosmus quadripetiolus (Fig. 2) and the K2P genetic divergence between them was 6.1%.

Cytocrome b gene tree including all the sequences available for Dryocosmus spp. Tree topology was inferred using Bayesian inference with the substitution model HKY+ Gamma for the three codon positions. Support for each node is represented by the Bayesian probability value. Taxonomic identity of each sequence taken from GenBank, numbers besides scientific names indicate the accession numbers.

Due to the striking genetic divergence among cytb haplotypes we conducted a series of tests to detect potential nuclear mitochondrial pseudogenes (numts). First, we inspected carefully the 24 cytb chromatograms of the Iberian samples and in none of them there were double peaks. Moreover, when the cytb haplotypes (the two Iberian and the other two recorded in Italy and Hungary) were translated into aminoacids in none of them there were any stop codons; no indels were found either. Yet, this is not enough to discard the existence of numts22. The GC content of the D. kuriphilus haplotypes ranged from 22.5 to 22.9%, what falls within the limits expected for mitochondrial DNA22. However, the mutation rates and patterns of the D. kuriphilus haplotypes grouped in the independent cluster (all except Iberia 1) (Fig. 2) deviated significantly from the reference values, thereby showing that they could be nuclear copies of mitochondrial genes. The pairwise comparison between the haplotype collected in Italy and Hungary and the haplotype Iberia 2 (we did not include the Italian DQ286803 because the sequence was almost identical to Iberia 2) showed that mutation rates in the second codon position exceeded by far the values expected in mitochondrial DNA (Table 2). For this reason, the relative frequency of nonsynonymous substitutions also exhibited extremely high values. Moreover, the relative frequencies of transversions and transitions in the third codon position did not agree with those reported for mitochondrial DNA, they were too high and too low respectively (Table 2). We got similar results when we compared the D. kuriphilus haplotypes of the separate cluster with the haplotype Iberia 1 or the closely related species Dryocosmus quadripetiolus (Table 2; Fig. 2). By contrast, when the sequences of the haplotype Iberia 1 and Dryocosmus quadripetiolus were compared, mutation rates agreed with those expected for mitochondrial DNA (Table 2) in all the parametres, with just a very slight deviation in the case of transversions and nonsynonimous substitution rates.

Discussion

Our comparison across-genes evidences the extremely low genetic diversity of the populations of the invasive D. kuriphilus in Europe, according with previous studies based on a single-gene5. The null intra-specific divergence of the nuclear 28S rDNA agrees with the slow mutation rates of this gene, which has shown little or no variability even between hymenoptera species of the same genus17. The gene ITS2 showed no variability either, despite nuclear internal transcribed spacers have shown inter-population variability in bees23. Moreover, we found no indels or nucleotide substitutions (absence of double peaks in the chromatograms) like those found in other insect species24. ITS2 homozigosity in D. kuriphilus is not surprising considering that one route to ITS intra-individual variability is the combination of different haplotypes inherited via sexual reproduction25 and this wasp is thelytokous (fertile eggs by parthenogenesis). However, variability might still arise through mutations, as in other species multiple clones of this gene may be found in the same individual24. The lack of variability could thus support the hypothesis on the low number of founders in the invasive populations.

The unique haplotype of the mitochondrial gene cox1 retrieved in the Iberian samples was shared with all the chestnut gall wasps sequenced from central Europe and northern Italy5 and with one of the six haplotypes recorded in China18. The gene tree including all the sequences labelled as D. kuriphilus in GenBank depicted two clusters with little genetic variability within each. The haplotype found in Europe for C. sativa grouped with haplotypes retrieved from wasps feeding on different species of Castanea spp.: C. mollissima, C. henryi, and C. seguinii in China18. The second cluster corresponded to wasps collected only on C. henryi21. The existence of cox1 haplotypes with a higher genetic divergence with respect to the rest had been reported before5,18, but their phylogenetic relatedness remained unknown. The present gene tree shows that they form a monophyletic group that would correspond to Dryocosmus zhuili, a new species that feeds only on C. henryi recently described on a morphological basis21. The absence of C. henryi in Europe would hinder the invasion by this more specialised species. By contrast, the wider trophic range of D. kuriphilus in its native range (it has been recorded on different host trees: C. crenata, C. mollissima, C. henryi, and C. seguinii)26 could have facilitated the colonization of a new host tree (C. sativa) not present in China, as a wide trophic niche generally favours pests27.

The European haplotype of cox1 was the most widespread one in China18. The arrival of the most frequent haplotype in the native distribution range to the invaded areas reflects a typical founder effect28. The rare alleles are less likely to reach the new populations founded after an invasion event, resulting in a decrease of the overall genetic diversity29. The mitochondrial gene 16S also showed null genetic variability but, as we sequenced it for the first time in the genus Dryocosmus, we could not compare it with any sequence from elsewhere in the native or invasive distribution range.

The striking intra-specific genetic divergence in cytb was provoked by the presence of pseudogenes. The genetic distance between the two D. kuriphilus cytb haplotypes recorded in Iberia largely exceeds the usual intra-specific genetic divergence reported for other Dryocosmus spp.26. Such intraspecific divergence also exists in the invasive populations of Italy and Hungary, but it had gone unnoticed because the sequences were reported by two different studies17,26. These values are also extremely high compared to the intraspecific variability reported for other mitochondrial genes (e. g. cytochrome oxidase I), which was generally below 1%30,31.

Exaggerated intra-specific genetic divergence in a mitochondrial gene often indicates the existence of mitochondrial nuclear insertions (numts)32; however, the sequences did not fulfil some of their characteristics. The typical double peaks in the chromatograms and their combination forming chimeric sequences33,34 were not detected, moreover, no stop codons or indels were found in any of the four haplotypes either. Nonetheless, further analyses showed that some of those haplotypes were really pseudogenes. Three of them formed a separate clade in the cytochrome b gene tree, whereas the remaining one (haplotype Iberia 1) was closer to other species of Dryocosmus (Fig. 2). The elevated rates in the second codon position, the proportions of transitions/transversions in the third codon position and the high rate of nonsynonymous substitutions showed that the haplotypes in the separate clusters were nuclear copies of the mitochondrial gene (numts). Only the haplotype Iberia 1 was genuine mitochondrial DNA.

The pseudogenes found in D. kuriphilus share some characteristics with those reported in other organisms. Studies with small mammals have shown that cytb pseudogenes also form separate clades in the gene trees35. Likewise, numts usually appear in the phylogeny in a basal position, with shorter branches from the common ancestor compared to the mitochondrial gene and closer to sister species33,34,35.

The infection by Wolbachia, may account for the high genetic divergence recorded in some species of insects36, yet it cannot explain our results. Wolbachia is a symbiont intracellular bacteria maternally inherited that increases the fitness of the females that bear it37. It has also male-killing abilities and promotes parthenogenetic reproduction, what favours the rapid spread of the haplotypes infected by Wolbachia thereby reducing the genetic diversity of the populations. Extreme intra-specific genetic divergence may occur when there is a Wolbachia-driven introgression. If a male mates with a female of a closely related species infected by Wolbachia and the offspring females are fertile, a new and very divergent mitochondrial haplotype could spread if the hybrid female backcrosses with the father’s species36. In Dryocosmus kuriphilus Wolbachia infection has been reported in some populations, but no males have been recorded so far11, what excludes this introgression scenario. Furthermore, as mitochondrial DNA does not recombine, such divergence should exist in all mitochondrial genes38 and it only occurs in cytb.

The detection of pseudogenes in D. kuriphilus recommends caution before drawing any conclusion in phylogenetic and population genetic studies. In fact, the sequences reported by other studies and uploaded to GenBank turned out to be pseudogenes17,25. In our study site we recorded both genuine mitochondrial DNA and pseudogenes, if well the real mitochondrial cytb was sequenced in the majority of the individuals (75%). We stress the need of performing in silico analyses of the sequences22 to detect them and interpret the results properly.

Despite their potential confounding effects, the mitochondrial copies of mitochondrial genes (numts) may provide interesting information about the species demography34. Previous studies have shown that clusters of numts may be orthologous34, that is, they would result from an ancient insertion of mtDNA in the nuclear genome and subsequent duplications. This might be the case of at least two of the pseudogene haplotypes recorded in our study (Iberia 1 and the Italian DQ286803), as they differ in only one base. If they were orthologous, we could not state that there have been multiple introductions in Europe from its native range, but at least say that not all the D. kuriphilus are clones because the invasion might have started with more than one individual.

Conclusion

Dryocosmus kuriphilus exhibits a very low genetic diversity, probably favoured by its strict parthenogenetic reproduction and the infection of Wolbachia (in the case of mtDNA)11. In its European invasive range genetic diversity is even lower as a consequence of the founder effect. Nuclear markers with low mutation rates (28S and ITS) and mitochondrial genes (citox1, cytb and 16S) have no variability in Europe. In the case of cytb we detected one pseudogene in some individuals from our study sites and two more from other European localities. The existence of pseudogenes stresses the need of performing careful in silico sequence analyses when working with mitDNA in this species. The pseudogenes may provide interesting information, though. Two of them might be orthologous and, if so, the invasion might have started with more than one individual, not all chestnut gall wasps in Europe would be clones. Future studies including more localities within the European invasive range and using preferably highly variable nuclear markers such as SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) will show the expansion routes of this pest that is provoking dramatic economic losses.

Methods

Study area and species

The study was carried out in the Refugio del Juanar, locality of Marbella (province of Málaga, 36° 34.79′ N 04° 53.13′ O, 820 m.s.l). In this area it is possible to find naturalized chestnut stands forming relict woodlands, as well as orchards for nut production, being an important economic resource for local farmers39.

The chestnut gall wasp D. kuriphilus (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) is a species native to Asia that was accidentally introduced in Italy in 20023. In the Iberian Peninsula it was first detected in the northeast in 20129; in the study area the first record dates from 2014. D. kuriphilus is an univoltine species, females oviposit into the buds in early summer dying afterwards. Larvae hatch and overwinter within the dormant buds until the following spring. Budburst starts in April in our study area, and the new branchlets that develop from infested buds grow abnormally forming fleshy galls on the shoots and leaves. Larvae feed and grow within those galls for approximately a month and then pupate, more than one larva are usually found together within the same gall. The fully developed adults drill an exit emergence hole to leave the gall in June15, then they fly and look for new buds to oviposit. Females do not need to copulate as they are telythokous; parthenogenesis is the only reproductive strategy known and to date as only females have been found11.

Sampling

Samples were collected during April and May 2015 in the area where the pest was first detected in southern Spain. Grown galls were picked from the trees in three nearby sites distant approximately 100 m (36° 34.7′ N – 36° 34.9′ N; 4° 53.1′ O – 4° 53.3′ O). In total, 389 galls were taken to the laboratory and opened to extract the larvae, which were immediately kept in ethanol 100% for further molecular analyses. From these larvae we randomly selected 24 (8 from each sampling site), which were taken to the genetics laboratory for DNA extraction and sequencing. The comparison of larval DNA with published reference sequences from previously determined individuals has proved as a very useful method of identification and assessment of unequivocal trophic relationships between plants and insects40.

Laboratory methods

DNA was extracted from larval tissue according to the salt extraction protocol41. For each individual we then amplified a total of five genes, two nuclear (28S and ITS2) and three mitochondrial (cytochrome oxidase I, cytochrome b and 16S). We chose those genes because for most of them (with the exception of 16S) there were reference sequences in GenBank to compare with. Also, mitochondrial DNA mutation rates are higher than those of nuclear DNA and intraspecific genetic divergence could differ between these two types of markers15.

For the nuclear gene 28S rDNA (D3-D5 region) and the mitochondrial DNA coding for the protein cytochrome b we used the primers and PCR protocols described in Sartor et al. (2012, ref.15); for the nuclear ITS2 (ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer region 2), located between the genes coding for the 5.8S and 28S rRNA, we followed Ji et al. (2003, ref.42). In the case of the mitochondrial 16S, coding for the large ribosomal subunit (16S rRNA), we employed general primers that have been used in a wide range of arthropods43. By last, the fragment of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome oxidase I, commonly used as universal DNA barcode, was amplified using the primers LEP (R1) and LEP (F1)44.

Sequencing was run on a 3730XL DNA analyser and sequences were edited using SEQUENCHER 4.1 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The chromatograms were carefully inspected to detect double peaks that, in the case of mitochondrial DNA, could be indicating the presence of nuclear insertions of mitochondrial DNA segments (so called numts)31,32 and, in nuclear genes, heterozygosity at a certain locus or multiple copies of the same gene23,24. All sequences were stored at the public repository GenBank.

When the edition was over the sequences of all genes, with the exception of the mitochondrial 16S rDNA, were aligned with all the haplotypes available at GenBank for each one. Alignments were created using CLUSTALW supplied via http://align.genome.jp (gap open and gap extension penalties were those provided by default by the software, 15 and 6.66 respectively). Sequences were trimmed on the extremes to reduce the proportion of missing data (see alignment lengths in Table 3). The alignment matrix of each gene was inspected using MacClade software version 4 to detect variable sites45. Both cox1 and cytb were translated into to aminoacids with a double objective: i) test for the presence of stop codons in the middle of the sequences of these intronless functional genes, as that would be also an indication of the presence of numts31,32, and ii) calculate the codon positions for further bayesian phylogenetic inference.

For the genes showing any variability we calculated the pairwise genetic distance using the software MEGA746. The distance between sequences was computed following two methods: i) the Kimura 2 Parameters model (K2P)47 and ii) the uncorrected genetic distance (total number of variable sites over the whole DNA sequence). We also used MEGA 7 to assess mutation rates, transitions/tranversions and nonsynonymous substitution rates in the in silico analyses to detect potential nuclear copies of mitochondrial DNA22.

We built two separate gene trees based on cytochrome oxidase I and cytochrome b. We did so to assess the phylogenetic position of the Iberian haplotypes of D. kuriphilus with respect to haplotypes of the same species from other geographic areas and also with respect to other species of the same or allied genera. We chose those genes due to the higher number of sequences available at GenBank. For cytochrome oxidase I we pooled the Iberian D. kuriphilus sequences with those reported from China18, Central Europe5 and Italy17. This last study also provided sequences from other allied genera of gall wasps that were included in the gene tree. In the case of cytochrome b we built the tree using exclusively sequences of species within the genus Dryocosmus. This was possible due to the availability of cytochrome b sequences for a total of 24 Dryocosmus spp.17,25.

Gene trees were built following Bayesian inference using Mr Bayes 3.248 applying the substitution model estimated by Partition Finder 1.1.149. The best substitution models were assessed by Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): for cytochrome oxidase I one partition was defined for each of the three codon positions, being the substitution model HKY + Gamma for the first and third and F81 + inv for the second position. In the case of cytochrome b, it grouped the 1st and 2nd codon positions on one side and left the 3rd in a separate partition; HKY + Gamma was the model selected in both of them. For the Bayesian inference two parallel runs of 10 million generations each were conducted using one cold and two incrementally heated Markov chains (Λ = 0.2), sampling every 1,000 steps. We first checked the standard convergence diagnostics implemented in MrBayes and then assessed the average standard deviation of the split frequencies to deduce that the Markov chain had reached stationarity. After 500,000 generations, the average standard deviation of the split frequencies stabilized in values close to zero (0.001). Hence, phylogenetic trees were summarized using the all-compatible consensus command with 25% burn-in. In the two gene trees Barbotinia oranensis was used as outgroup (as in Ács et al. (2007, ref.17).

References

Paini, D. R. et al. Global threat to agriculture from invasive species. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 7575–7579 (2016).

Battisti, A., Benvegnù, I., Colombari, F. & Haack, R. A. Invasion by the chestnut gall wasp in Italy causes significant yield loss in Castanea sativa nut production. Agr. Forest Entomol. 16, 75–79 (2014).

Quacchia, A., Moriya, S., Bosio, G., Scapin, I. & Alma, A. Rearing, release and settlement prospect in Italy of Torymus sinensis, the biological control agent of the chestnut gall wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus. BioControl 53, 829–839 (2008).

Brussino, G. et al. Dangerous Exotic Insect Threatening European Chestnut. Informatore Agrario 58, 59–61 (2002).

Avtzis, D. N. & Matosevic, D. Taking Europe by storm: a first insight in the introduction and expansion of Dryocosmus kuriphilus in central Europe by mtDNA. J. For. Soc. Croatia 137, 387–394 (2013).

Bernardo, U. et al. Biology and monitoring of Dryocosmus kuriphilus on Castanea sativa in Southern Italy. Agr. Forest Entomol. 15, 65–76 (2013).

Sartor, C. et al. Impact of the Asian wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Yasumatsu) on cultivated chestnut: Yield loss and cultivar susceptibility. Sci Hortic. 197, 454–460 (2015).

Çetin, G., Orman, E. & Polat, Z. First record of the Oriental chestnut gall wasp, Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) in Turkey. Bitki Koruma Bülteni 54, 303–309 (2014).

Pujade-Villar, J. & Torrell, A. Primeres troballes a la península Ibèrica de Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Hym., Cynipidae), una espècie de cinípid d’ origen asiàtic altament perillosa per al castanyer (Fagaceae). Orsis 27, 295–302 (2013).

Mena, J. D. et al. Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae) en poblaciones de castaño de la provincia de Málaga. Proceedings of the National Spanish Congress of Applied Entomology. Valencia, Spain, (2013).

Zhu, D. H., He, Y. Y., Fan, Y. S., Ma, M. Y. & Peng, D. L. Negative evidence of parthenogenesis induction by Wolbachia in a gall wasp species. Dryocosmus kuriphilus. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 124, 279–284 (2007).

Graziosi, I. & Rieske, L. K. Potential Fecundity of a Highly Invasive Gall Maker, Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). Environ. Entomol. 43, 1053–1058 (2014).

EFSA. Risk assessment of the oriental chestnut gall wasp, Dryocosmus kuriphilus for the EU territory and identification and evaluation of risk management options. EFSA Journal 8, 1619 (2010).

Ferracini, C. et al. Post-Release evaluation of non-target effects of Torymus sinensis, the biological control agent of Dryocosmus Kuriphilus in Italy. Biocontrol, https://doi.org/10.1007/S10526-017-9803-2 (2017).

Sartor, C., Marinoni, D. T., Quacchia, A. & Botta, R. Quick detection of Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) in chestnut dormant buds by nested PCR. B. Entomol. Res. 102, 367–371 (2012).

Stone, G. N. et al. The phylogeographical clade trade: tracing the impact of human-mediated dispersal on the colonization of northern Europe by the oak gall wasp Andricus kollari. Mol. Ecol. 16, 2768–2781 (2007).

Ács, Z., Melika, G., Pénzes, Z., Pujade-Villar, J. & Stone, G. N. The phylogenetic relationships between Dryocosmus Chilaspis and allied genera of oak gall wasps (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae: Cynipini). Syst. Entomol. 32, 70–80 (2007).

Lu, P. F., Zhu, D. H., Yang, X. H. & Liu, Z. Phylogenetic analysis of mtDNA COI gene suggests cryptic species in Dryocosmus kuriphilus associated with certain populations of Chinese chestnuts (Castanea spp.). Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 49, 161–167 (2012).

Oliveira, D. C. S. G., Raychoudhury, R., Lavrov, D. V. & Werren, J. H. Rapidly evolving mitochondrial genome and directional selection in mitochondrial genes in the parasitic wasp Nasonia (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 2167–2180 (2008).

Kaltenpoth, M. et al. Accelerated evolution of mitochondrial but not nuclear genomes of hymenoptera: New evidence from crabronid wasps. Plos One 7, e32826 (2012).

Zhu, D. H. et al. New gall wasp species attacking chestnut trees: Dryocosmus zhuili ssp. (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) on Castanea henryi from southeastern China. J. Insect Sci. 15, 1–7 (2015).

Arthofer, W., Avtzis, D. N., Riegler, M. & Stauffer, C. Mitochondrial phylogenies in the light of pseudogenes and Wolbachia: Re-assessment of a bark beetle dataset. ZooKeys 56, 269–280 (2010).

Ruiz, C., De May-Itzá, W. J., Quezada-Euán, J. J. G. & De La Rúa, P. Utility of the ITS1 region for phylogenetic analysis in stingless bees: A case study of the endangered Melipona yucatanica Camargo, Moure and Roubik (Apidae: Meliponini). Sociobiology 61, 470–477 (2014).

Shapoval, N. A. & Lukhtanov, V. A. Intragenomic variations of multicopy ITS2 marker in Agrodiaetus blue butterflies (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae). Comp. Cytogenet. 9, 483–497 (2015).

Kajtoch, L. & Lachowska-Cierlik, D. Genetic Constitution of Parthenogenetic Form of Polydrusus inustus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) -Hints of Hybrid Origin and Recombinations. Folia biologica (Kraków) 57, 149–156 (2009).

Tang, C. T. et al. New Dryocosmus Giraud species associated with Cyclobalanopsis and non-Quercus host plants from the Eastern Palaearctic (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae, Cynipini). J. Hymenoptera Res. 53, 77–162 (2016).

Bonal, R. et al. Diversity in insect seed parasite guilds at large geographical scale: the roles of host specificity and spatial distance. J. Biogeogr. 43, 1620–1630 (2016).

Roman, J. Diluting the founder effect: cryptic invasions expand a marine invader’s range. P. Roy. Soc. Lond. B Bio. 273, 2453–2459 (2006).

Neilson, M. E. & Wilson, R. R. mtDNA singletons as evidence of a post-invasion genetic bottleneck in yellowfin goby Acanthogobius flavimanus from San Francisco Bay, California. Mar. Ecol-Prog Ser. 296, 197–208 (2005).

Ratnasingham, S. & Hebert, P. D. N. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (www.barcodinglife.org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 355–364 (2007).

Bergsten, J. et al. The Effect of Geographical Scale of Sampling on DNA Barcoding. Syst. Biol. 61, 851–869 (2012).

Berthier, K., Chapuis, M. P., Moosavi, S. M. & Tohidi-Esfahani, D. G. A. Nuclear insertions and heteroplasmy of mitochondrial DNA as two sources of intra-individual genomic variation in grasshoppers. Syst. Entomol. 36, 285–299 (2011).

Triant, D. A. & DeWoody, J. A. The Occurrence, Detection, and Avoidance of Mitochondrial DNA Translocations in Mammalian Systematics and Phylogeography. J. Mammal. 88, 908–920 (2007).

Dubey, S., Michaux, J., Brünner, H., Hutterer, R. & Vogel, P. False phylogenies on wood mice due to cryptic cytochrome-b pseudogene. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 50, 633–641 (2009).

Triant, D. & DeWoody, J. A. Demography and phylogenetic utility of numt pseudogenes in the Southern Red-Backed Vole (Myodes gapperi). J. Mammal. 90, 561–570 (2009).

Fry, A. J., Palmer, M. R. & Rand, D. M. Variable fitness effects of Wolbachia infection in Drosophila melanogaster. Heredity 93, 379–389 (2004).

Charlat, S. et al. The joint evolutionary histories of Wolbachia and mitochondria in Hypolimnas bolina. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 1–9 (2009).

Montelongo, T. & Gómez-Zurita, J. Non-random Patterns of Genetic Admixture Expose the Complex Historical Hybrid Origin of Unisexual Leaf Beetle Species in the Genus Calligrapha. The American Naturalist 185, 113–134 (2015).

Martín, M. A., Moral, A., Martín, L. M. & Alvarez, J. B. The genetic resources of European sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Miller) in Andalusia, Spain. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 54, 379–387 (2007).

Bonal, R., Espelta, J. M. & Vogler, A. P. Complex selection on life-history traits and the maintenance of variation in exaggerated rostrum length in acorn weevils. Oecologia 167, 1053–1061 (2011).

Aljanabi, S. M. & Martinez, I. Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4692–4693 (1997).

Ji, Y. J., Zhang, D. X. & He, L. J. Evolutionary conservation and versatility of a new set of primers for amplifying the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer regions in insects and other invertebrates. Mol. Ecol. Notes 3, 581–585 (2003).

Kambhampati, S. & Smith, P. T. PCR primers for the amplification of four insect mitochondrial gene fragments. Insect Mol. Biol. 4, 233–236 (1995).

Hebert, P. D. N., Penton, E. H., Burns, J. M., Janzen, D. H. & Hallwachs, W. Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterfly Astraptes fulgerator. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 14812–14817 (2004).

Maddison, D. R. & Maddison, W. P. MacClade 4: Analysis of phylogeny and character evolution. 2005; Version 4.08a. http://macclade.org (2005).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–120 (1980).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Lanfear, R., Calcott, B., Ho, S. Y. W. & Guindon, S. Partitionfinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1695–1701 (2012).

Acknowledgements

RB and AMC are grateful to the Secretaría General de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación de la Consejería de Economía e Infraestructuras from the Regional Government of Extremadura (Spain) for the financial support (Atracción de Talento Investigador Programme). We are also grateful to Jesús Gómez-Zurita for valuable conversations on the results previous to manuscript writing. Comments of two anonymous reviewers contributed to improve a previous version of the manuscript. This research was partially supported by projects PPII-2014-01-P from Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha and AGL2013-48017-C2-1-R, AGL2014-54739-R and AGL2014-53822-C2-1-R from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) from the European Union.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B. participated in the genetics labwork, data analyses and manuscript writing. E.V.O. and J.D.M. participated in the field sampling and wasp identification in the lab. M.S. and J.M.A. worked in the genetics lab. A.M.C. participated in the data analyses and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonal, R., Vargas-Osuna, E., Mena, J.D. et al. Looking for variable molecular markers in the chestnut gall wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus: first comparison across genes. Sci Rep 8, 5631 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23754-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23754-z

This article is cited by

-

Gall size of Dryocosmus kuriphilus limits down-regulation by native parasitoids

Biological Invasions (2021)

-

Tracking seasonal emergence dynamics of an invasive gall wasp and its associated parasitoids with an open-source, microcontroller-based device

Journal of Pest Science (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.