Abstract

In the current study, the thermodynamics of the slag-metal equilibrium reaction between Inconel 718 Ni-based alloy and CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 electroslag remelting (ESR)-type slags were systematically investigated in the temperature range from 1773 to 1973 K (1500 to 1700 °C). The equilibrium Al content increased with increasing temperature, whereas the equilibrium Ti content decreased with increasing temperature at a fixed slag composition. The important factors for controlling the oxidation of Al and Ti in the Inconel 718 superalloy were TiO2 > Al2O3 > CaO > CaF2 > MgO in ESR-type slag and Al > Ti in a consumable electrode. The conventional method of sampling by means of a quartz tube could result in contamination of the molten metal and changes in the size of the “special reaction interface”. Therefore, a novel method was used in the present study to investigate the slag-metal reaction kinetics to accurately obtain the kinetic parameters. The mass transfer coefficient was determined by coupling with the kinetic model derived from the assumption that the reaction rate ([Al] + (TiO2) = [Ti] + (Al2O3)) was controlled by the mass transfer of [Ti], [Al], (TiO2) and (Al2O3) in the boundary layer, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inconel 718 is extensively used for aerospace and other components that operate at high temperatures and in corrosive environments, where materials with both high strength and excellent corrosion resistance are required1,2,3,4,5. The increasing demand for alloys with remarkable comprehensive performance necessitates the development of alloys with highly uniform microstructures and highly homogeneous composition. Electroslag remelting (ESR) is well known for cleanliness and homogeneity of the solidification structure of the resultant ingot. The poor homogeneity of the ingot’s composition, however, illustrates that some problems with the process remain unsolved6,7. Strong chemical reactions usually occur at the electrode-slag interface (ESI) or the droplet-slag interface (DSI) as well as at the metal pool-slag interface (MSI), as shown in Fig. 18. Consequently, in some cases, the concentrations of critical elements cannot be maintained within specifications or the elements cannot be uniformly distributed along the height of the ingots during the ESR process9.

Numerous studies of the aforementioned issues have been reported. The approaches mainly involve encapsulating a preformed consumable electrode by covering the cap between the electrode and water-cooled mold and blowing inert gases onto the surface of the slag bath10,11,12, adding an aluminium shot to the slag bath or an aluminium coating to the electrodes to reduce oxidation of the slag caused by rust on the surface of the consumable electrode and by air above the slag pool12,13,14. Furthermore, the oxidation of Ti and Al in Inconel 718 is unlikely to be avoided, as demonstrated by the following equilibrium between Al2O3 and TiO2 in the CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-based slag6:

Therefore, determining the thermodynamic equilibrium between the reactive elements considered and oxide components in ESR slag is very important to diminish the loss of Al and Ti during the ESR process.

In the present study, the dependence of the equilibrium content of Al in Inconel 718 on each component in CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slag in the temperature range from 1773 to 1973 K (1500 to 1700 °C) was investigated. Meanwhile, the effect of the Al content on the equilibrium Ti content in the Ni-based alloy was also studied, through which the appropriate composition of the consumable electrode was obtained.

Under conventional conditions, the melt-quenching method is used to investigate chemical reaction kinetics; that is, slag and metal samples are periodically collected using quartz tubes and quenched in ice water, which is the most commonly used approach15. However, the liquid metal containing reactive elements such as Al, Ti, rare-earth elements (REE), etc., can react with the quartz tube, viz., 4[Al] + 3SiO2 = 2Al2O3 + [Si], resulting in contamination of the molten metal16. In addition, the net flux of species i in the slag or the metal phase can be written as

where k i , \(\frac{A}{V}\), \({C}_{i}^{\ast }\) and C i represent the mass transfer coefficient of component i (m/s), the ratio of the interfacial reaction area to the effective liquid melt volume (we introduce the concept of “specific reaction interface” (SRI) (1 /m) in the present study, and concentrations at the slag-metal interface and in the bulk (mol/m3), respectively. The preceding experimental technique can increase the SRI value, either because of the turbulence of the reaction interface or because of a decrease in the absolute amount of melts during sampling17. Consequently, the changes in the value of the SRI cause the integration of Eq. (2) to become more complex and inconvenient16.

To solve the aforementioned problems, we investigated the reaction kinetics of Inconel 718 alloy with CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags using laboratory-scale experiments, which we conducted under the same experimental conditions (concentration, temperature, and protective atmosphere) by using several identical crucibles with the same melt contents. Meanwhile, we derived a kinetic model using the fundamental equation of heterogeneous reaction kinetics based on the concept of effective boundary layer proposed by Wagner to obtain kinetic parameters18.

Thermodynamic considerations

According to reaction (1), the relationship between the equilibrium content of Al in Inconel 718 and variables such as the activity a i of components i in CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags, chemical constitution of the consumable electrode, and the temperature of the slag can be obtained by simple mathematical derivation.

Calculating the equilibrium content of Al requires that the relevant parameters be obtained: (I) The mass action concentration (activity) N i of each component in the slag can be calculated using the reported activity model (for details of the modelling and solution procedure, see Eqs (1) through (3) in ref.19) based on the ion and molecule coexistence theory (IMCT)20. The basic meaning of N i is consistent with the traditionally applied activity a i in the slag, in which pure solid matter is chosen as the standard state and mole fraction is selected as a concentration unit. According to the hypothesis of the IMCT20,21,22, CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slag is composed of four simple ions (Ca2+, Mg2+, O2− and F−), two simple molecules (Al2O3 and TiO2), and approximately 15 complex species according to the reported binary and ternary phase diagrams in the temperature range from 1773 to 1973 K (1500 to 1700 °C)23. The chemical reaction formulas of complex molecules that are possibly formed, their standard Gibbs free energy changes \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{{\rm{r}}}{G}_{{\rm{m}},{\rm{c}}i}^{{\rm{\theta }}}\), the mole number n i , mass action concentration N i and the equilibrium constant \({K}_{{\rm{c}}i}^{{\rm{\theta }}}\) in 100 g CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags are listed in Table 1. The mass action concentration of complex molecules can be expressed by \({N}_{{{\rm{CaF}}}_{2}}\)(N1), NCaO(N2), \({N}_{{{\rm{Al}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{3}}\)(N3), NMgO(N4), \({N}_{{{\rm{TiO}}}_{2}}\)(N5) and \({K}_{{\rm{c}}i}^{{\rm{\theta }}}\). (II) The activity coefficient f%,i of Al and Ti can be calculated using the Wagner equation18; the interaction coefficients used in the present study are listed in Table 2. The chemical composition of Inconel 718 alloy is listed in Table 3. (III) The temperature range investigated during the ESR process was 1773 to 1973 K (1500 to 1700 °C).

The relationship between the calculated equilibrium Al content for a given Ti content (1.13) and the slag composition of component i in CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags in the temperature range from 1773 to 1973 K (1500 to 1700 °C) is illustrated in Fig. 2. The equilibrium Al content increases with increasing temperature at a constant slag composition. The dependence of the determined equilibrium Al content on the CaO content in the slag (CaF2:XCaO:Al2O3:MgO:TiO2 = 37:XCaO:25:3:10) at different temperatures is illustrated in Fig. 2(a). The figure shows a continuous increase in the equilibrium Al content with increasing addition of CaO. The calculated equilibrium Al content is greater than 0.43 (the Al content in the master alloy used in the present study) under appropriate conditions, viz., the temperature is greater than 1923 K (1650 °C) and (% CaO) > 22.68, which indicates that Al is not subject to oxidation. This phenomenon is consistent with the results of Jiang et al.24, who reported that the high CaO content in CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2-SiO2 slags can prevent the oxidation of Al in GH8825 during the ESR process. Similar results are shown in Fig. 2(b). In Fig. 2(c), the calculated equilibrium Al content in the molten metal at various temperatures is plotted against the TiO2 content. The equilibrium Al content decreases sharply under conditions of (% TiO2) < 1.1, and the point of intersection of the equilibrium Al content line and the isoconcentration line ([% Al] = 0.43) is shifted to the high-TiO2-content side when the temperature is increased. Similarly, Hou et al.25 found that the slag containing a low CaO content combined with extra TiO2 constantly added into the molten slag in the first temperature-rising period is suitable for electroslag remelting of 1Cr21Ni5Ti stainless steel. Figure 2(d) illustrates the evolution of the calculated equilibrium Al content in the Ni-based alloy when the proportion of MgO in the molten slag is different (0 ≤ (% MgO) ≤ 9.35), which shows that the equilibrium Al content decreases with increasing MgO content. At the temperature of 1923 K (1650 °C), as Fig. 2(d) shows, the equilibrium Al content is always less than 0.43 over the full composition range of MgO, indicating that satisfying the smelting requirements of Inconel 718 alloy only by adjusting the mass content of MgO in the molten slag is difficult. However, the oxidation of Al in the Ni-based alloy can be damped when the mass percent of MgO is less than 5.83% at 1973 K (1700 °C). A similar behaviour in the dependence of the equilibrium Al content is observed in Fig. 2(e).

The relationship between calculated equilibrium Ti content for a given Al content (0.43) and the slag composition of component i in CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags in the temperature range from 1773 to 1973 K (1500 to 1700 °C) is illustrated in Fig. 3. It can be observed that the equilibrium Ti content shows negative correlation with temperature in the range of 1773 to 1973 K (1500 to 1700 °C) with constant slag composition. Meanwhile, the effect of mass percent for CaO, Al2O3, TiO2, MgO, and CaF2 as components in CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags on the equilibrium Ti content illustrated in Fig. 3 shows completely opposite trend compared with Fig. 2.

As it is previously discussed, the effects of MgO and CaF2 on controlling the equilibrium Al content in Ni-based alloy compared that of TiO2, CaO, and Al2O3 in CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags are very mild. Zaitsev et al.26,27 also demonstrated that the activities of CaO and Al2O3 were not substantially changed by addition of CaF2 to the CaF2-CaO-Al2O3 slag system. However, CaF2 plays an important role in the ESR process to improve the fluidity and conductivity of the slag28. Therefore, the importance of factors for controlling the equilibrium Al content in Inconel 718 is ordered as TiO2 > Al2O3 > CaO > CaF2 > MgO in ESR slags.

To elaborate the Inconel 718 alloy composition design, the influence of slag composition on the calculated equilibrium Al content for five different Ti contents (0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.1 and 1.3) at 1873 K (1600 °C) is shown in Fig. 4, from which it can be found that all above mentioned observations in Fig. 2 are consistent with the trend shown in Fig. 4. The equilibrium Al content increases with increasing Ti content for a given slag composition at a constant temperature, which reveals that, on the prerequisite of satisfying the mechanical properties of the alloy, to properly increases Ti content can prevent oxidation of Al in the Inconel 718 superalloy. The influence of slag composition on the calculated equilibrium Ti content is shown in Fig. 5, which shows that the calculated equilibrium Ti content increases with increasing Al content (0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8). The determined equilibrium Ti content is greater than 1.13 for a fixed Al content at 0.8 in the full composition range of slag composition of component i in CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags ((% TiO2) > 3.23). However, the determined Al content for the upper limit Ti content (1.3) is less than 0.43 over the full composition range of slag composition ((% TiO2) > 6.25) shown in Fig. 4. These results demonstrate that the Al and Ti content in the consumable electrode can be designed to be the upper limit in the case where some mechanical properties are met, which is an effective method of controlling Al and Ti loss during the ESR process. What’s more, it can be obtained by comparing Figs 4 and 5 that the importance of factors for preventing oxidation of active elements in Inconel 718 is ordered as Al > Ti in the consumable electrode.

Experimental Materials and Methods

Metal and slag preparation

To begin the experiment, Inconel 718 alloy samples were produced in a MgO crucible in a vacuum-induction melting (VIM) furnace under a high-purity argon atmosphere; the chemical composition is listed in Table 3. Each of the master alloys was cut into a smaller size (1 to 3 cm3) to facilitate weighing. Analar-grade CaF2, CaO, MgO, Al2O3, and TiO2 were used as raw materials. The thoroughly mixed powders were melted at 1773 K (1500 °C) in a graphite crucible under a high-purity Ar atmosphere to ensure complete melting and homogenization; the liquid sample was then quenched on the cooled copper plate and ground. The chemical composition of the experimental slag is listed in Table 4.

Experimental apparatus and process

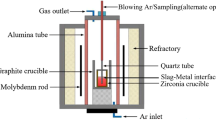

The slag-metal equilibrium reaction between CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slags and Inconel 718 alloy was conducted in a vertical resistance-heated alumina tube furnace equipped with MoSi2 heating elements. Figure 6 shows a schematic of the resistance furnace used in the present study. The temperature of the furnace was controlled by a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller connected to a B-type reference thermocouple. The temperature was calibrated to 1773 K (1500 °C) using another B-type thermocouple before the experiment. The kinetic experiments were carried out using the double-layer (DL) graphite crucible shown in Fig. 7. The experimental procedure is briefly summarized in steps as follows:

-

(1)

Pre-melted slag (12 g) was held in the upper graphite crucible with a small hole in its bottom after a carbon stopper was used to plug the hole. The inner wall of the upper crucible makes an angle of 110 degrees with the bottom to ensure that the melted slag drops fully into the lower separate crucible. Face-cleaned Inconel 718 alloy (22 g) was accommodated in a MgO crucible (ID: 25 mm; OD: 30 mm; H: 35 mm). The MgO crucible was then placed in the lower graphite crucible (ID: 31 mm; OD: 36 mm; H: 40 mm) to prevent the reactant from leaking.

-

(2)

The DL crucible with reactants was placed in a graphite tray, which was then positioned in the constant-temperature zone of a resistance furnace after the furnace temperature reached the pre-set temperature of 1773 K (1500 °C). High-purity Ar was flushed into the reaction chamber at a constant flow rate to avoid the oxidation of the Ni-based alloy.

-

(3)

Prior to the experiment, the time required for the slag and metal to melt completely was estimated; these estimates indicated that the samples had fully melted after the graphite crucible was placed into the resistance furnace for 10 min.

-

(4)

The moment the carbon stopper was removed (viz., the moment contact occurred between the molten slag and metal) was taken as the starting time of the reaction. After certain reaction time intervals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 10 min), the whole crucible containing liquid samples was rapidly removed from the furnace and quenched in ice water. The flow sheet for the experimental procedure is shown in Fig. 8. After completion of the experiments, the composition of the Ni-based alloy samples was analysed by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES).

Figure 7

Results and Discussion

Oxidation behaviour of Al and Ti through CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 slag

According to the calculated results in the section on ‘Relationship between equilibrium content of Al or Ti and slag composition at different temperatures’, three laboratory-scale experiments (T1, T2 and T3) with different slag compositions (Fig. 2(c)) were performed at 1773 K (1500 °C). The changes in concentration of Al and Ti in the metal phase are shown in Fig. 9 as a function of time for various slags. Figure 7(a) shows that the Al2O3 in molten slag was rapidly reduced by Ti during the first 3–5 min, after which the Al2O3 remained nearly constant. Similar results are also observed in Fig. 7(c). The Al and Ti contents remained constant as functions of time. Full details of the experimental results are given in Table 4. These results indicate that the calculated equilibrium content of Al and Ti in the metal phase shows reliable agreement with the measured values.

Establishment of the kinetic model

The interface chemical reaction is generally accepted to be rapid at metallurgical temperatures, which gives rise to the fact that the overall reaction rate is controlled only by mass transfer of a species to or from the slag-metal interface through the concentration boundary layer17. On the basis of this theory of Wagner29, the main assumptions in the developed kinetic model for elucidating the probable reaction mechanism between molten slag and Ni-based alloy can be briefly summarized as follows: (I) Only two phases (liquid slag and Ni-based alloy) are considered. (II) The interface chemical reaction reaches a local equilibrium at metallurgical temperatures, and this equilibrium does not control the overall rate of reaction. (III) Reactant and product do not accumulate at the slag-metal interface, and the mass transfer resistance occurs mainly at the boundary layer.

Therefore, reaction (1) may be divided into the following elementary steps:

-

(1)

Mass transfer of [Al] in the Ni-based alloy from the bulk to the slag-metal interface: [Al] → [Al]*;

-

(2)

Mass transfer of (TiO2) in the molten slag from the bulk to the slag-metal interface: (TiO2) → (TiO2)*;

-

(3)

Interface chemical reaction: 4[Al]* + 3(TiO2)* = 3[Ti]* + (Al2O3)*;

-

(4)

Mass transfer of [Ti]* in the Ni-based alloy from the slag-metal interface to the bulk: [Ti]* → [Ti];

-

(5)

Mass transfer of (Al2O3)* in the Ni-based alloy from the slag-metal interface to the bulk: (Al2O3)* → (Al2O3).

According to the fundamental equation of heterogeneous reaction kinetics based on the concept of the effective boundary layer, the flux of component i across unit area J i is defined as Eq. (4). A schematic of the effective boundary layer is shown in Fig. 10. The derivation process of the fundamental equation of heterogeneous reaction kinetics has been presented in detail elsewhere18.

If the mass transfer of Ti in liquid metal is the rate-controlling step, the following equation can be deduced by inserting a relationship between the molar concentration and mass concentration terms:

where DTi, δTi and hm represent the diffusion coefficient of Ti (m2/s), the thickness of the boundary layer in the metal phase (m), and the thinness of the molten metal (m). The equilibrium constant of the interface chemical reaction (1) can be written as:

where a%,i and f%,i are the activity and activity coefficient of composition i in a metal referred to the 1% standard state, with mass percentage [% i] as the concentration unit (−) and aR,i and γ i are the activity and activity coefficient of composition i in the slag relative to pure matter as a standard state, with mole fraction x i as the concentration unit (−).

In view of the small change in the composition of the components included in reaction (1) (e.g., Al, Ti, Al2O3, and TiO2), the activity coefficient for each aforementioned component can be regarded as approximatively constant. In particular, high concentrations of Al2O3 are found in the present study, indicating that the activity \({a}_{{{\rm{Al}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{3}}\) of Al2O3 can also be treated as a constant. These constants are hence incorporated into the equilibrium constant K of reaction (1). The collated equilibrium constant K1 can be expressed as

The maximum mass transfer rate of Ti in liquid metal can be obtained by substituting the mass percent at the slag-metal interface, i.e. [% Al]* and (% TiO2)*, with the mass concentration in bulk, as shown in Eq. (9):

The concentration [% Al] of Al in the bulk metal and the (% TiO2) of TiO2 in the bulk slag in Eq. (9) can be associated with the [% Ti] in the bulk metal via a stoichiometric relationship at any time during the reaction process:

where (% TiO2)0 and [% Al]0 represent the total amounts of TiO2 in the slag and Al in the molten metal, respectively. Combining Eq. (9) with Eqs (10) and (11), we obtain the following equation after simple mathematical derivation:

where Δ[% Ti] = [% Ti]t = t − [% Ti]t = 0 is the difference between the concentration of Ti in the liquid metal at time t and that at time zero. The model for TiO2 diffusion in the slag, Al diffusion in the metal, and Al2O3 diffusion through a slag boundary layer have also been derived with respect to the Ti content in the bulk metal in a parallel manner:

For mass transfer of Al in metal phase control,

For mass transfer of Al2O3 in slag phase control,

where K2 = ([% Ti]*3(% Al2O3)*2)/([% Al]*4(% TiO2)*3) and \({Q}_{2}=\frac{2}{3}\frac{{W}_{{\rm{m}}}}{{W}_{{\rm{s}}}}\frac{{M}_{{{\rm{Al}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{3}}}{{M}_{{\rm{Ti}}}}\).

Inspection of Eqs (12)–(15) shows that they can both be represented as a function of mass concentration of Ti in the bulk metal:

When the maximum mass transfer rate models for Ti and Al in the metal (Eqs (12) and (14)) and TiO2 and Al2O3 in the slag (Eqs (13) and (15)) are valid, the plot of F[(% Ti)] versus time t should give a straight line and the mass transfer coefficient k i can be acquired from its slope. For this purpose, the regressed formula of [% Ti] in the metal phase against the reaction time t can be expressed as a nonlinear function:

Figure 11 shows the data from Fig. 7(c) replotted according to Eqs (12)–(15). Although the experimental data appears to fit the line well, only the linear relationship between F[(%Ti)] and time t does not assure the mass transfer in the metal phase or the slag phase of being RCS. Therefore, the RCS and apparent activation energy of oxidation of Al and Ti in the Ni-based alloy by ESR slags will be carried out in the future. Certainly, the mass transfer rate of Al and Ti in the metal phase is much larger than the mass transfer rate of TiO2 and Al2O3 in the slag phase, rendering the mass transfer of TiO2 and/or Al2O3 in the slag phase likely to be the rate-controlling step. These results have been experimentally confirmed by several authors25,30,31. Recently, Hou et al.25 reported on the effect of slag composition on the oxidation kinetics of alloy elements during ESR of stainless steel experimentally using a 50-kg ESR furnace. They concluded that the rate-determining step of the oxidation reaction was the mass transfer of Al2O3 through the molten metal, SiO2 through the slag and TiO2 through both the metal and the slag phase.

Conclusions

In the present study, the thermodynamic analysis for the slag-metal equilibrium reaction between Inconel 718 Ni-based alloy and CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO-TiO2 ESR-type slags at various temperatures was systematically discussed. Meanwhile, the reaction mechanism was also investigated, coupling with the max mass transfer rate model. Our results are summarized as follows.

-

(1)

The equilibrium Al content showed a positive correlation with temperature in the range from 1773 to 1973 K (1500 to 1700 °C) with a constant slag composition, whereas the equilibrium Ti content showed the opposite trend.

-

(2)

The equilibrium Al and Ti contents depended weakly on the CaF2 and MgO contents in the studied slags, irrespective of the temperature, indicating that MgO can be used to tailor the physicochemical properties of the slags.

-

(3)

The thermodynamic results obtained from the IMCT calculation were in good agreement with the measurement results. The importance of factors for controlling the oxidation of Al and Ti in Inconel 718 superalloy was TiO2 > Al2O3 > CaO > CaF2 > MgO in ESR-type slag and Al > Ti in the consumable electrode.

-

(4)

The calculated results for controlling oxidation of reactive elements in the Ni-based alloy were in good agreement with the experimental results. An appropriate amount of TiO2 additive in the ESR slag can be quantitatively determined so that Al and Ti are not subject to oxidation during the ESR process.

-

(5)

The kinetic model was applied to the oxidation of Al in the Ni-based alloy by ESR slags. The results indicated that the mass transfer rate of Al and Ti in the metal phase was much larger than the mass transfer rate of TiO2 and Al2O3 in the slag phase.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Knorovsky, G. A., Cieslak, M. J., Headley, T. J., Romig, A. D. & Hammetter, W. F. Inconel 718: A solidification diagram. Metall. Trans. A. 20, 2149–2158 (1989).

Rahman, M., Seah, W. K. H. & Teo, T. T. The machinability of Inconel 718. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 63, 199–204 (1997).

Pawade, R. S., Joshi, S. S. & Brahmankar, P. K. Effect of machining parameters and cutting edge geometry on surface integrity of high-speed turned Inconel 718. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 48, 15–28 (2008).

Ulutan, D. & Ozel, T. Machining induced surface integrity in titanium and nickel alloys: A review. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 51, 250–280 (2011).

Liu, Y. C. et al. Recent progress on evolution of precipitates in Inconel 718 superalloy. Acta Metall. Sin. 52, 1259–1266 (2016).

Pateisky, G., Biele, H. & Fleischer, H. J. The Reactions of titanium and silicon with slags Al2O3-CaO-CaF2 in the ESR process. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 9, 1318–1321 (1972).

Li, S. J. et al. A Thermodynamic model to design the equilibrium slag compositions during electroslag remelting process: description and verification. ISIJ Int. 57, 713–722 (2017).

Melgaard, D. K., Williamson, R. L. & Beaman, J. J. Controlling remelting processes for superalloys and aerospace Ti alloys. JOM-US. 50, 13–17 (1998).

Li, Z. B. Electroslag metallurgy theory and practice (eds Liu, X. F. et al.), 141–148 (Metallurgical Industry Press, 2010).

Wegman, D. D., Compositional control and oxide inclusion level comparison of pyromet@718 and A-286 ingots electroslag remelted under air vs. argon atmosphere. Superalloys 1988: Proceedings of the sixth international symposium on superalloys sponsored by the high temperature alloys committee of the metallurgical society of AIME, (1988).

Chen, X. et al. Investigation of oxide inclusions and primary carbonitrides in Inconel 718 superalloy refined through electroslag remelting process. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 43, 1596–1607 (2012).

Shi, C. B., Chen, X. C., Guo, H. J., Zhu, Z. J. & Ren, H. Assessment of oxygen control and its effect on inclusion characteristics during electroslag remelting of die steel. Steel Res. Int. 83, 472–486 (2012).

Choudhury, A. State of the art of superalloy production for aerospace and other application using VIM/VAR or VIM/ESR. ISIJ Int. 32, 563–574 (1992).

Reyes-Carmona, F. & Mitchell, A. Deoxidation of ESR slags. ISIJ Int. 32, 529–537 (1992).

Kim, M. et al. A reaction between high mn-high al steel and CaO-SiO2-type molten mold flux: part I. Composition evolution in molten mold flux. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 44, 299–308 (2013).

Wang, C. Z. Research methods in metallurgical physical chemistry (eds Song, L. et al.), 492–494 (Metallurgical Industry Press, 2013).

Pomfret, R. J. & Grieveson, P. The kinetics of slag-metal reactions. Can. Metall. Quart. 22, 287–299 (1983).

Guo, H. J. Metallurgical physical chemistry (ed Yang, Y. Y.), 105–108 (Metallurgical Industry Press, 2013).

Duan, S. C., Guo, X. L., Guo, H. J. & Guo, J. A manganese distribution prediction model for CaO–SiO2–FeO–MgO–MnO–Al2O3 slags based on IMCT. Ironmak. Steelmak. 44, 168–184 (2017).

Zhang, J. Computational thermodynamics of metallurgical melts and solutions (ed Liu, X. F.), 241–245 (Metallurgical Industry Press, 2007).

Zhang, J. The calculating model of mass action concentrations for the slag system Na2O-SiO2. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing. 11, 208–212 (1989).

Zhang, J. Calculating model of mass action concentrations for the slag system MnO-SiO2. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing. 8, 1–6 (1986).

Eisenhüttenleute, V. D. & Allibert, M. Slag atlas. (Woodhead Publishing Ltd., 1995).

Jiang, Z. H. et al. Effect of slag on titanium, silicon, and aluminum contents in superalloy during electroslag remelting. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 47, 1465–1474 (2016).

Hou, D. et al. Effect of Slag Composition on the Oxidation Kinetics of Alloying Elements during Electroslag Remelting of Stainless Steel: Part-2 Control of Titanium and Aluminum Content. ISIJ Int. 57, 1410–1419 (2017).

Zaitsev, A. I., Korolyov, N. V. & Mogutnov, B. M. Thermodynamic properties of (xCaF2 + yAl2O3 + (1− x− y) CaO)(l) I. Experimental investigation. J. Chem. Therm. 22, 513–530 (1990).

Zaitsev, A. I., Korolyov, N. V. & Mogutnov, B. M. Thermodynamic properties of (xCaF2 + yAl2O3 + (1− x− y) CaO)(l) II. Model description. J. Chem. Therm. 22, 531–543 (1990).

Duckworth, W. E. & Hoyle, G. Electroslag Refining. (Chapman & Hall, 1969).

Wagner, C. & Elliott, J. F. The physical chemistry of steelmaking. (John Wiley & Sons, 1958).

Chen, C. X., Gao, R. F. & Zhao, W. X. Effect of slag composition on Mg, Al or Ti content in Ni-based superalloy during ESR. Acta Metall. Sin. 20, 137–145 (1984).

Chen, C. X., Wang, Y., Fu, J. & Chen, E. P. A study on the titanium loss during electroslag remelting high titaium and low aluminum content superalloy. Acta Metall. Sin. 17, 50–57 (1981).

Jerzak, W. & Kalicka, Z. Activity coefficients of manganese, silicon and aluminum in iron, nickel and Fe-Ni alloys. Arch. Metall. Mater. 55, 441–447 (2010).

Karasev, A. & Suito, H. Quantitative evaluation of inclusion in deoxidation of Fe-10 mass pct Ni alloy with Si, Ti, Al, Zr, and Ce. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 30, 249–257 (1999).

Pak, J. et al. Thermodynamics of titanium and nitrogen in an Fe-Ni melt. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 36, 489–493 (2005).

Yoshikawa, T. & Morita, K. Influence of alloying elements on the thermodynamic properties of titanium in molten steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 38, 671–680 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The author (Shengchao Duan) would like to express their sincere thanks to Dr. Fei Wang of Research Institute of High Temperature Materials, Central Iron and Steel Research Institute (CISRI) helped to design the experimental apparatus. Ph.D. Bin Li, Shao-ying Li and Xue-liang Zhang of School of Metallurgical and Ecological Engineering, and Professor Cheng-bin Shi as well as Ph.D. Ding-li Zheng of State Key Laboratory of Advanced Metallurgy (SKL) at University of Science and Technology Beijing (USTB) contributed to the discussion of the results. The authors are also thankful to the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos U1560203 and 51274031).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shengchao Duan wrote the article and made all the figures and tables in this article. Hanjie Guo and Jing Guo provided many suggestions for the designing of experiments. Xiao Shi, Ming-Tao Mao, Shao-Wei Han, and Wen-Sheng Yang contributed to perform the experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, S., Shi, X., Mao, M. et al. Investigation of the Oxidation Behaviour of Ti and Al in Inconel 718 Superalloy During Electroslag Remelting. Sci Rep 8, 5232 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23556-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23556-3

This article is cited by

-

Thermodynamic and Physical Properties of CaF2–(Al2O3–TiO2–MgO) System Slags for Electroslag Remelting of Inconel 18 Alloy

Materials Science (2023)

-

Oxygen Transfer Mechanism of ESR-Slag at Different Atmospheric Oxygen Contents

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (2022)

-

Determination of real-time oxygen transfer rate based on an electrochemical method

Journal of Iron and Steel Research International (2022)

-

Effect of Temperature on the Oxidation Behavior of Al and Ti in Inconel® 718 Alloy by ESR Slag with Different Amounts of CaO

JOM (2022)

-

Oxidation Behavior of K4750 Alloy at Temperatures Between 750 °C and 1000 °C

Acta Metallurgica Sinica (English Letters) (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.