Abstract

The aim of the study was to describe the sociodemographic and clinical features of the mothers and their offspring staying with them in prison. The study was planned as a cross-sectional, single-center study of mothers residing in Tarsus Closed Women’s Prison of Turkish Ministry of Justice along with their 0 to 6 years old offspring. Mothers were evaluated via Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. A psychologist blind to maternal evaluations applied the Denver Developmental Screening Test II (DII-DST). Children/mothers were also evaluated by a child and adolescent psychiatrist via K-SADS-PL. Twenty-four mothers with a mean age of 29.3 years were included. Most common diagnoses in mothers were nicotine abuse (n = 17, 70.8%), specific phobia (n = 8, 33.3%), alcohol abuse (n = 7, 29.2%) and substance abuse (n = 5, 20.8%). Twenty-six children (53.9% female) were living with their mothers in prison, and the mean age of those was 26.3 months. Results of the D-II-DST were abnormal in 33.3% of the children. Most common diagnoses in children were adjustment disorder (n = 7, 26.9%) separation anxiety disorder (n = 3, 11.5%) and conduct disorder (n = 2, 7.7%). A multi-center study is necessary to reach that neglected/under-served population and address the inter-generational transmission of abuse, neglect, and psychopathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“Conviction” and “imprisonment” are important stress factors for psychopathology. Those experiences involve separation from friends, relatives, and acquaintances, loss of freedom, self-esteem, and privacy. Life in prison brings with its restrictions, lack of control and choice1,2. Previous studies carried out in various countries reported that psychiatric problems were more common in prisoners compared to the community3,4,5,6. The prevalence of psychopathology varied between 43.0% from Australia to 94.0% from Canada. The prevalence in Turkish population samples was in between those rates (i.e. 67.2%)3,4,5,6,7. Female prison inmates may be especially prone to develop psychopathology7. Motherhood is an important experience in the life of females, and the experience of being an imprisoned mother can be especially traumatic8,9. Conviction and imprisonment interfere in various ways with motherhood experience such as limited communication with offspring and relatives, abrupt visits with long intervals, giving birth and raising children in prison, etc8,9.

According to official data 6287 Turkish women inmates (3.7% of total) were serving prison sentences in 2015 and current prison policies allows mothers with children up to 6 years old to serve sentences together. Approximately five thousand of those inmates are estimated to have children up to 18 years old (Mandiraci10). A recent report found that 668 children through the country were in prisons with their mothers (Anonymous11). This option is afforded to all incarcerated women with children and there is no legal limit to the number of children who can stay with their mothers. Once the children are 6 years old they were sent to the parent outside of prison or grandparents/ other relatives pending on the familial situation. Although all women inmates are offered free academic and vocational courses during their sentences children received relatively little attention. Prison kindergartens and opportunities to foster development are limited (Mandiraci10).

Despite the importance of studying inmate populations, especially the vulnerable ones like women and children and adolescents for psychopathology from a public health perspective, research on those are scarce. Young children living in prisons along with their mothers may be especially prone to psychopathology. Therefore, this study was conducted to evaluate the socio-demographic and clinical features of the mothers and their infant to −6 years old offspring staying with them in prison. In a literature review, to our knowledge, there was no previous study evaluating both mental status and development of children who live with their mothers in prison.

Materials and Methods

Study Center and Participants

The study was planned as a cross-sectional, single-center study of mothers residing in Tarsus Closed Women’s Prison of Turkish Ministry of Justice along with their 0 to 6 years old offspring. The study protocol was approved by Baskent University Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee (Project no: KA16/221) and Turkish Ministry of Justice. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in Declaration of Helsinki and National Code of Clinical Research. The criteria for inclusion were having infant to 6 years old offspring in prison, having sufficient Turkish fluency, normal level of intellectual functioning. Exclusion criteria were a lack of Turkish fluency and sub-average intellectual functioning. At the time of the study, the prison housed 309 inmates of which 27 had infant to 6 years old offspring staying in prison together. One was not fluent in Turkish and none were judged to have sub-average intellectual functioning rendering clinical evaluations ineffective. Two mothers refused to provide Informed Consent for participation leading to a final sample of 24 mothers with 26 children in prison.

Instruments

Prison Experience and Socio-demographic data Evaluation Form

This form was developed by the researchers and aimed to evaluate the socio-demographic features of mothers and their offspring. The form included information on mental disorders experienced both after and prior to imprisonment, any treatments received, attempts at self-harm and/or suicide, smoking and use of alcohol/illicit substances, family history of psychopathology, reasons for imprisonment, duration of imprisonment and prior experiences of imprisonment.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)

This is a structured, clinical interview to evaluate DSM-IV Axis I disorders involving six modules and diagnostic criteria of 38 diagnoses. It was developed by First and colleagues12 and adapted to Turkish in 1999. The Turkish form was demonstrated to have adequate reliability and validity13.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

This 21- item self-report inventory was developed by Beck et al. to evaluate levels of subjectively reported depressive symptoms14. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version were established by His et al.15. Each item is assessed on a 4-point Likert-type scale, and the cut-off for clinically significant depressive symptoms in Turkish version was reported to be 1716.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

This 21-item self-report of anxiety symptoms is also graded on a 4-point Likert-type scale with higher scores denoting elevated anxiety levels. It was developed by Beck and colleagues17 and reliability and validity of the Turkish version were reported by Ulusoy18.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MDSPS)

This 12-item, 7-point Likert-type self-report scale with scores ranging from 12 to 84 was developed to evaluate subjective levels of social support by Zimet and colleagues19. The scores are deemed to correlate with levels of perceived social support. Moreover, reliability and validity of the Turkish version were reported by Eker and Arkar20.

Childhood Trauma Screening Questionnaire- 53 item version (CTSQ-53)

This self- report scale for assessment of retrospective recollections of childhood traumatic experiences and neglect was initially developed as consisting of 70 items21 with later modifications leading to 53 and 28 item versions. All forms are 5-point Likert-type scales with subscales for emotional, physical and sexual abuse during childhood and physical and emotional neglect. The Turkish versions were found to be reliable and valid previously.22Here CTSQ-53 is used.

Denver-II- Developmental Screening Test (D-II-DST)

This screening test was initially developed in 1967 for developmental screening of 0 to 6 years old children. Multiple translations of the original exist and all demonstrated cross-cultural reliability and validity. The original test was revised in 1990, forming the Denver- II- Developmental Screening Test and reliability and validity of the Turkish version was established by Anlar and Yalaz22.

Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version-Turkish Version (K-SADS-PL-T)

K-SADS is a semi-structured interview to evaluate both present and lifetime pediatric psychiatric diagnoses according to DSM-IV-TR criteria23. The Turkish version was found to be reliable and valid previously24.

Study procedure

In this study mothers imprisoned with their 0 to 6 years, old offspring were evaluated via SCID-I. They later completed forms for BDI, BAI, MDSPS, CTSQ-53 for themselves (with help from the study team for the illiterate). Prison Experience and Socio-demographic data Evaluation Form was completed by mothers and the study clinicians. A psychologist blind to maternal evaluations applied the D-II-DST by interviewing mothers and children. Children and mothers were also evaluated by a child psychiatrist via K-SADS- PL to determine psychopathology. The main aims of the study were to describe the socio-demographic and clinical features of the mothers and their infant-6 years old offspring.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 22.0. Descriptive analyses were used to summarize data. Nominal and ordinal data were summarized as frequencies while metric data were summarized either as means and standard deviations or medians and inter-quartile ranges depending on outliers/ normality. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Results

Socio-demographic, clinical and psychometric results of mothers

Twenty-four mothers with a mean age of 29.3 (S.D. = 6.5) years were included in this study. The median period of incarceration was 365.0 days (IQR = 625.0). The mothers’ socio-demographic and clinical features were illustrated in Table 1.

Mean scores of mothers in CTSQ-53 were 10.9 (S.D. = 4.2, Range = 5.5–20.6) points. When previously reported cut-offs for the Turkish version of the CTSQ-53 was used19; all mothers scored in clinical ranges for emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect while none scored in the clinical range for total scores.

The majority of the mothers were married and home-makers (n = 23, 95.8%). For the majority, the marriage ceremony was religious (n = 13, 54.2%) and they had other offspring living outside of prison (n = 18, 75.0%). The level of education was low with ten being illiterate (41.7%) and 2 of the mothers being barely literate (8.3%). Apart from those most of the remaining had a secondary level of education (n = 8, 33.3%). Maternal grandparents were also mostly illiterate (62.5% and 45.8% for grandmothers and grandfathers; respectively). The spouses of the women were educated mostly at the secondary (33.3%) or primary (25.0%) school levels and worked mostly as unqualified workers (62.5%). Income of the families was mostly below the poverty level (83.3%). Three of the women were imprisoned with pending trials (12.5%) while the rest received their sentences and were serving them. For those with terms to serve mean duration remaining was 5.9 years (S.D. = 6.8). The crimes were theft (62.5%), substance use/dealing (20.8%) and murder (12.5%), in decreasing frequency. Half of the women were imprisoned previously for varying durations and offenses while 41.7% reported that their spouses and 70.8% indicated that other family members were currently serving prison terms. Almost half (41.7%) of the women stated that they were receiving treatment for chronic medical conditions (mostly asthma; n = 7, 29.2%).

A third of the mothers reported contact with mental health services before their imprisonment while 9 of them (37.5%) were receiving psychiatric treatment as prison inmates at the time of the study. Evaluation with SCID-I revealed psychopathology in the majority (n = 17, 70.8%), almost half receiving no treatment (Table 2). The family history of psychopathology was elicited from 45.8% of the mothers. Self- reported domestic abuse (54.2%) and history of self-harm (45.8%) was common while self- reported sexual abuse was rarer (8.3%).

Sociodemographic, clinical and psychometric results of children

The median number of children reported by mothers were 3.0 (IQR = 8.0). Most of the mothers had one child living in prison while two mothers have two of their children each, living along. Twenty-six children (53.9% female) were living with their mothers at the time of the study, and the mean age of those was 26.3 (S.D. = 16.1) months. Delivery for those children was mostly uncomplicated/vaginal and at term (75.0% and 79.2%; respectively). Motor- mental developmental milestones of children are listed in Table 3.

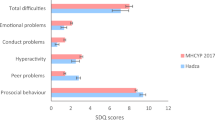

Children were living in prison along with their mothers for a median of 195.0 days (IQR = 375.0). Fifteen of the children (57.7%) were attending the prison kindergarten. Most (80.8%) could play with their toys in the prison while 45.8% could draw pictures/use pencils. However, only 4 of the children (15.4%) had books read to them by their mothers and/or spent special time together. Results of the D-II-DST were abnormal in 33.3% of the children. Additionally, one of the children had cerebral palsy (3.9%). Half of the children received psychiatric diagnosis via semi-structured evaluation by a child psychiatrist (Table 4). None of those children was previously evaluated by child psychiatrists, and they had been given no treatment previously.

Discussion

This single center, cross- sectional study of imprisoned mothers living with their infant to 6 years old offspring in Tarsus, Turkey aimed to evaluate their socio-demographic characteristics and clinical features of mothers and their offspring. As a result, we found that those mothers were mostly illiterate, poor and without formal education, their marriages were mostly religious, they had other family members serving/served prison times and that they have elevated rates of family psychopathology, domestic abuse, and self- harm. Motor-mental developmental milestones in offspring were within normal limits on average, although one-third showed signs of developmental delays. Imprisonment interfered with motherhood in our sample. The majority of the mothers and half of the offspring met criteria for psychopathology. Most common disorders in mothers were nicotine abuse, specific phobia and alcohol abuse while most common disorders in offspring were adjustment disorder, separation anxiety, and conduct disorder. Half of the mothers with psychopathology and all of the children with psychopathology were not receiving treatment for their problems.

Research has consistently shown that prisoners have high rates of psychiatric disorders globally25 although the status of imprisoned women has been relatively neglected7,8,9. Previous studies from US and UK reported rates of psychopathology among female inmates as being 70.0 to 76.0%8,9. Most of those studies reported that alcohol and substance abuse are relatively common with PTSD following closely8,9. Boşgelmez et al. indicated that the rate of lifetime suicide attempts/self- harm as 50.0% in her sample while that of domestic abuse was 63.3%7. In that study, rates for nicotine, substance, and alcohol abuse were found to be 60.0%, 13.3%, and 6.7%; respectively. Although there are other isolated studies conducted on Turkish women prison inmates, none focused on psychopathology per se26,27. All studies focusing on psychopathology among women inmates reported that despite their elevated levels, those disorders were frequently under-diagnosed and poorly treated. In our study, consistent with the literature, evaluation with SCID-I revealed psychopathology in the majority of women with almost half receiving no treatment and about one-third receiving psychiatric treatment as prison inmates at the time of the study. Rates for nicotine abuse were also similar to those previously reported.

According to Turkish Institute of Statistics; women formed 3.7% of the 173.814 people convicted/imprisoned in 2015. Also, according to those data, imprisoned women were mostly poorly educated, between 25–29 years and most common crimes committed were theft and producing/selling illicit substances28,29,30. Similar to the official statistics and previous literature, our sample of imprisoned/convicted women was also mostly uneducated and from lower socio-economic levels. The age range and committed crimes were also consistent with previous studies and reports.

Social support for prison inmates may involve friends, family, and institution and helps to protect their physical and psychological health7. Boşgelmez et al.7 reported that perceived social support among her sample in prison is significantly lower for female inmates and Çoban et al.29 indicated that women in prison perceived a moderate level social support. Consistent with those reports and according to MDSPS scores, the level of social support in our sample was also moderate.

The relationship between criminal offending and early childhood adverse experiences is one of the widely reported and supported tenets of developmental psychopathology. It is also valid for female offenders30,31,32,33,34. In our study, consistent with the literature all inmate mothers scored in clinical ranges for emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. It is also widely known that childhood adverse experiences increase the risk for developing internalizing and externalizing disorders over the lifespan35,36. We also found elevated rates of psychopathology in our sample. This finding may be due to limited and biased sample, recall and/or reporting bias and should be replicated with further studies.

The preschool period is a critical time for developing skills in various domains, and its effects are felt through the lifespan of the individual37. In children with risk factors, developmental delays are among the most frequently observed problems with a 3–25% prevalence in the first six years of life38. Risk factors identified in the literature that compromise children’s development and the developing brain include biological (e.g. stunting, infections, anemia, preterm birth), psychosocial (e.g., inadequate cognitive stimulation, exposure to violence, household dysfunction), socio-demographic risk factors (e.g., poverty)39,40,41,42 and poor mental health in mothers43. Childhood trauma and domestic violence in mothers themselves, as well as teenage motherhood, are also significant risks for the cognitive delay44,45,46. On the other hand; protective factors against delayed child development in at-risk samples include; daily interaction with child (i.e. reading, imitation games, singing), higher parenting self-efficacy, higher social support and community engagement47. Such protective factors may be especially important in imprisoned mothers48. Drastically, children spent imprisonment time with their mother in unacceptable and overpopulated prisons, and they become victims of the system similar to our findings. A recent report on the status of more than 1500 children of imprisoned parents from various countries of European Union found that parental imprisonment affects children independently of national affluence and conditions in prison in different ways. Those include stigmatization, separation/attachment issues, confusion/ambiguity about parents’ loss/incarceration. According to those results, mental health problems in those children are elevated, especially for those younger than 11 years49. Accordingly, modification in arrest/policing processes, consideration of children’s perspectives in legal proceedings and the importance of receiving information about imprisonment from parents are suggested to promote resilience49. Although 668 children were reported to live with their mothers in the Turkish prison system, there were no previous reports other than ours to evaluate their psychological status and development (Anonymous11). Therefore we can report that our results are consistent with findings from EU countries but ecological validity for other samples of children living in other prisons should be evaluated.

Some of the features of the study setting may have affected our results. A vast majority of mothers were at the low socio-economic level, had a psychiatric disorder, got married and gave birth during adolescence period, and literacy rate was quite low. Moreover, 50 inmates stayed in a ward in prison and unfortunately children had to sleep in the same bed with their mothers. This feature may have elevated rates of separation anxiety disorder in our sample. A room of the prison was reserved as kindergarten, but there was no child-friendly environment. Sometimes other women were angry with children for being noisy and swore at them. Quarrels broke out frequently inwards increasing the children’s insecurity. Fortunately, most of the children in our sample could play with their toys in the prison while almost half could draw pictures/use pencils. However, only 4 of the children (15.4%) had books read to them by their mothers and/or spent special time together. Reflecting the adverse conditions, one-third of our sample of children was delayed in developmental milestones. Half of the children received psychiatric diagnosis via semi-structured evaluation by a child psychiatrist. The most common diagnoses were adjustment disorder (especially among recent arrivals/younger children), separation anxiety and conduct disorder. A more structured and enriched environment, special interaction times between mothers and their children, developmentally informed child care, structured curricula for imprisoned mothers in child development and positive disciplinary practices, providing developmentally appropriate information to children about their surroundings and circumstances may reduce rates of psychopathology and prevent inter-generational transmission of traumatic experiences48,49,50.

Conclusion

This single-center, cross- sectional study of mothers in prison living with infant to 6 years old offspring in Tarsus Closed Women’s Prison aimed to evaluate the mothers via semi-structured interviews for psychopathology and self-report scales for childhood trauma, perceived social support, depression and anxiety and their offspring with developmental screening tests and semi-structured interviews. We found that the majority of mothers had low levels of education, living in poverty, married early and lacked civil protection for their marriages and offspring. Self- reports of domestic abuse and suicide were high while all mothers scored in clinical ranges for emotional abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect in self-reports. The majority had psychopathology, often unrecognized and untreated by the prison authorities. Most common diagnoses in mothers were nicotine abuse, specific phobia, alcohol and substance abuse and those with psychopathology tended to have elevated CTSQ-53 sexual abuse scores.

Children in prison were often neglected by their mothers themselves. Half of those fulfilled criteria for psychopathology while one-third were delayed in developmental screening tests. Most common diagnoses in children were adjustment disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and conduct disorder. None of the children with psychopathology were previously evaluated, and none received previous treatment. The main limitations of our study are its cross-sectional nature and dependence on mothers as sole informants. Sampling, recall and reporting bias may also have affected our results. There may also be differing motives for mothers to report problems in their offspring (i.e. to seek treatment, to have their sentences reduced and/or being granted extra privileges by the prison administration). Regardless of its limitations, this study shows that both imprisoned mothers and their preschool offspring may be under elevated risk of psychopathology and that their psychopathology may be often unrecognized. A multi-center study, preferably under the aegis of the Turkish Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry to evaluate mothers imprisoned with their 0 to 6 years old offspring may be necessary to reach this neglected and under-served population and address the inter-generational transmission of abuse, neglect, and psychopathology. Furthermore, we suggest opening child and mother-friendly prisons with special rooms, creches, and playgrounds. As per suggestions outlined in EU reports; modification in arrest/policing processes, consideration of children’s perspectives in legal proceedings and the importance of receiving information about imprisonment from parents may promote resilience and reduce psychopathology in offspring49.

References

Blaauw, E., Arensman, E., Kraaij, V., Winkel, F. W. & Bout, R. Traumatic life events and suicide risk among jail inmates: the influence of types of events, time period and significant others. J Trauma Stress 15, 9–16, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014323009493 (2002).

Keaveny, M. E. & Zauszniewski, J. A. Life events and psychological well-being in women sentenced to prison. Issues Ment Health Nurs 20, 73–89 (1999).

Baillargeon, J., Black, S. A., Pulvino, J. & Dunn, K. The disease profile of Texas prison inmates. Ann Epidemiol 10, 74–80 (2000).

Butler, T., Allnutt, S., Cain, D., Owens, D. & Muller, C. Mental disorder in the New South Wales prisoner population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 39, 407–413, https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01589.x (2005).

Corrado, R. R., Cohen, I., Hart, S. & Roesch, R. Comparative examination of the prevalence of mental disorders among jailed inmates in Canada and the United States. Int J Law Psychiatry 23, 633–647 (2000).

Kaya, N., Güler, Ö. & Çilli, A. Konya Kapalı Cezaevi’ndeki mahkumlarda psikiyatrik bozuklukların yaygınlığı. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi 5, 85–91 (2004).

Bosgelmez, S. Psychological trauma and its consequences in female and male prisoners Unpublished Dissertation thesis, Kocaeli University (2006).

Parsons, S., Walker, L. & Grubin, D. Prevalence of mental disorder in female remand prisoners. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 194–202 (2001).

Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M. & McClelland, G. M. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women. I. Pretrial jail detainees. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53, 505–512 (1996).

Mandiraci B. Structural problems related to execution policies and instutions of criminal sentences in Turkey and suggestions for solutions. Turkish Foundation for Economic and Social Studies. Istanbul. 2015 [Turkish].

Anonymous. Press Release of the Network to Prevent Violence Against Children for World Children’s Day. 2017. [http://www.cocugasiddetionluyoruz.net/1152/20-kasim-dunya-cocuk-haklari-gununde-turkiyede-durum.html] Accessed on 20.11.2017.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M. & Williams, J. B. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Clinical Version (SCID-I/CV, Version 2.0). (New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1997).

Özkürkçügil, A., Aydemir, Ö., Yıldız, M., Danacı, A. E. & Köroğlu, E. DSM-IV Eksen I bozuklukları için yapılandırılmış klinik görüşmenin Türkçe’ye uyarlanması ve güvenilirlik çalışması. İlaç ve Tedavi Dergisi 12, 233–236 (1999).

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J. & Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4, 561–571 (1961).

Hisli, N. B. D. Envanterinin üniversite öğrencileri için geçerliği, güvenirliği. Psikoloji Dergisi 7, 3–13 (1989).

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G. & Steer, R. A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 56, 893–897 (1988).

Ulusoy, M. Reliability and validity study for Beck Anxiety Inventory. Unpublished Dissertation (1993).

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G. & Farley, G. K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment 52, 30–41 (1988).

Eker, D. & Arkar, H. Çok Boyutlu Algılanan Sosyal Destek Ölçeği’nin factor yapısı, geçerlik ve güvenirliği. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi 10, 45–55 (1995).

Bernstein, D. P. et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry 151, 1132–1136, https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132 (1994).

Şar, V. & Öztürk, E. & İkikardeş, E. Validity and Reliability of the Turkish Version of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci 32, 1054–1063 (2012).

Anlar, B. & Yalaz, K. Denver II gelişimsel tarama testi, Türk çocuklarına uyarlanması ve standardizasyonu. HÜTF Ped. Nöroloji Bilim dalı, 1–43 (1995).

Ambrosini, P. J. Historical development and present status of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39, 49–58, https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200001000-00016 (2000).

Gökler, B. et al. Reliability and Validity of Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version-Turkish Version (K-SADS-PL-T). Turk J Child Adolesc Ment Health 11, 109–116 (2004).

Fazel, S., Hayes, A. J., Bartellas, K., Clerici, M. & Trestman, R. Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 871–881, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30142-0 (2016).

Celik, H. A. A sociological analysis of women criminals in the Denizli Open Prison. Unpublished Dissertation for the Degree of Master of Science in Socioogy Dissertation thesis, Middle East Technical University (2008).

Baris, G. Female offenders’ attitudes towards gender and violence and their violence experiences: Sincan Women’s Prison. Unpublished Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology Dissertation thesis, Middle East Technical University (2015).

http://www.tuik.gov.tr (2017).

Çoban, A. İ. & Akgün, R. Figuring Out Of Psycho-social Conditions And Determination The Social Supports Of Women Who Stays in Ankara Closed Penal Institution for Women. Toplum ve Sosyal Hizmet 22, 63–78 (2011).

Ortaköylü, L., Taktak, Ş. & Balcıoğlu, İ. Women and Crime. Yeni Symposium 42, 13–19 (2004).

Putkonen, H., Weizmann-Henelius, G., Lindberg, N., Rovamo, T. & Hakkanen, H. Changes over time in homicides by women: a register-based study comparing female offenders from 1982 to 1992 and 1993 to 2005. Crim Behav Ment Health 18, 268–278, https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.711 (2008).

Rossegger, A. et al. Women convicted for violent offenses: adverse childhood experiences, low level of education and poor mental health. BMC Psychiatry 9, 81, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-9-81 (2009).

Starzyck, K. B. & Marhall, W. L. Childhood family and personological risk factors for sexual offending. Aggression and Violent Behavior 8, 93–105 (2003).

Weizmann-Henelius, G., Viemero, V. & Eronen, M. The violent female perpetrator and her victim. Forensic Sci Int 133, 197–203 (2003).

Kendler, K. S. et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57, 953–959 (2000).

Springer, K. W., Sheridan, J., Kuo, D. & Carnes, M. Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl 31, 517–530, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.01.003 (2007).

Hertzman, C. & Power, C. Child development as a determinant of health across the life course. Current Paediatrics 14, 438–443 (2004).

Eratay, E., Bayoglu, B. & Anlar, B. Preschool Developmental Screening with Denver II Test in Semi-Urban Areas. J Pediatr Child Care 1, 4 (2015).

Aboud, F. E. & Yousafzai, A. K. In Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 2) (eds R. E. Black, R. Laxminarayan, M. Temmerman, & N. Walker) (2016).

Bradley, R. H. & Corwyn, R. F. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu Rev Psychol 53, 371–399, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 (2002).

Grantham-McGregor, S. et al. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 369, 60–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4 (2007).

McCormick, M. C., Litt, J. S., Smith, V. C. & Zupancic, J. A. Prematurity: an overview and public health implications. Annu Rev Public Health 32, 367–379, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090810-182459 (2011).

Tough, S. C. et al. Maternal mental health predicts risk of developmental problems at 3 years of age: follow up of a community based trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 8, 16, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-8-16 (2008).

Dubowitz, H. et al. Type and timing of mothers’ victimization: effects on mothers and children. Pediatrics 107, 728–735 (2001).

Thompson, R. Mothers’ violence victimization and child behavior problems: examining the link. Am J Orthopsychiatry 77, 306–315, https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.306 (2007).

Morinis, J., Carson, C. & Quigley, M. A. Effect of teenage motherhood on cognitive outcomes in children: a population-based cohort study. Archives of disease in childhood 98, 959–964, https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-302525 (2013).

McDonald, S., Kehler, H., Bayrampour, H., Fraser-Lee, N. & Tough, S. Risk and protective factors in early child development: Results from the All Our Babies (AOB) pregnancy cohort. Research in developmental disabilities 58, 20–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2016.08.010 (2016).

Eloff, I. & Moen, M. An analysis of mother–child interaction patterns in prison. Early Child Development and Care 173, 711–720 (2003).

Philbrick, K., Ayre, L. & Lynn, H. The impact of imprisonment on the child. In: Children of Imprisoned Parents: European Perspectives on Good Practice. Second Edition edn, 41–64 (2014).

Luthar, S. S. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. (New York: Cambridge University Press 2003).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Baskent University Research Fund (Project no: KA16/221). We are very thankful to the staff of Tarsus Closed Women’s Prison of Turkish Ministry of Justice for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O.K., E.A., A.E.T., G.G., B.A., N.A. and O.K. designed the research, performed the experiments and analyzed data. M.O.K., E.A., N.A., and O.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kutuk, M.O., Altintas, E., Tufan, A.E. et al. Developmental delays and psychiatric diagnoses are elevated in offspring staying in prisons with their mothers. Sci Rep 8, 1856 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20263-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20263-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.