Abstract

Analysis of cloud cover and its diurnal variation over the Tibetan Plateau (TP) is highly reliant on satellite data; however, the accuracy of cloud detection from both polar-orbiting and geostationary satellites over this area remains unclear. The new-generation geostationary Himawari-8 satellites provide high-resolution spatial and temporal information about clouds over the Tibetan Plateau. In this study, the cloud detection of MODIS and AHI is investigated and validated against CALIPSO measurements. For AHI and MODIS, the false alarm rate of AHI and MODIS in cloud identification over the TP was 7.51% and 1.94%, respectively, and the cloud hit rate was 73.55% and 80.15%, respectively. Using hourly cloud-cover data from the Himawari-8 satellites, we found that at the monthly scale, the diurnal cycle in cloud cover over the TP tends to increase throughout the day, with the minimum and maximum cloud fractions occurring at 10:00 a.m. and 18:00 p.m. local time. Due to the limited time resolution of polar-orbiting satellites, the underestimation of MODIS daytime average cloud cover is approximately 4.00% at the annual scale, with larger biases during the spring (5.40%) and winter (5.90%).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Tibetan Plateau (TP), which is the highest and largest plateau on Earth, is well known to modulate regional and global atmospheric circulation by acting as an elevated heat source and a very large natural barrier1,2,3,4. The TP is more sensitive to temperature and humidity changes than the adjacent regions because of the much thinner air mass over the plateau5,6. The diurnal variation in cloud cover over the TP links convection and precipitation processes and has shown potential in disaster mitigation, precipitation forecasting and numerical-model validation. However, studies on these topics are scarce7,8,9, likely for the following three reasons: 1) a lack of ground observations of clouds10, 2) the limited temporal resolution of polar-orbiting satellites11,12, and 3) the inability of first-generation geostationary satellites to provide accurate cloud discrimination13,14,15. Thus, the accuracy of cloud discrimination from satellites over the TP is not fully understood.

Moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) cloud cover data have been used to investigate intra-seasonal variation in cloud cover over the TP5 and to validate the International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project (ISCCP) cloud climatology dataset16,17,18. The MODIS instrument is carried by the Terra and Aqua satellites, which follow descending and ascending orbits and cross the Equator at approximately 10:30 and 13:30 local time, respectively19. Inferred cloud-cover statistics from MODIS do not consider temporal variation in clouds. The cloud dataset from the newly launched Himawari-8 geostationary satellite that includes the Advanced Himawari Imager (AHI) with 16 bands that span from 0.47 µm to 13.3 µm, facilitates the accurate determination of cloud properties with a spatial resolution of 2 km and a temporal resolution of 10 min20. This determination is an important advancement that can show the spatial and temporal patterns of cloud cover and be used to analyze the diurnal variation of clouds. The AHI and MODIS identify clouds with similarly high spatial resolution, wide spectral coverage and a large area over the TP; however, they provide different viewing geometries and temporal resolutions. Thus, investigating semidiurnal cycles in cloud cover over the TP with AHI and MODIS can help elucidate the uncertainties of cloud-cover statistics that are estimated from polar-orbiting satellites.

However, the estimated cloud cover from both polar-orbiting and stationary satellites is not yet sufficiently assessed21. The MODIS cloud mask is seldom validated over the TP, and operational AHI cloud mask is still lacking detailed accuracy assessment. The topography over the TP is complex, with large regions of mountainous areas that are covered by snow and ice that may be considered erroneously to be clouds by satellites22,23. In general, current cloud detection algorithms have not considered the unique topography and cloud characteristics of the TP21. Therefore, the accuracy of MODIS and AHI cloud detections need to be evaluated before adopting their data to investigations of cloud cover variation.

The aims of this study are to 1) validate the cloud detections from AHI and MODIS over the TP and 2) investigate deviations in monthly daytime average cloud cover as calculated from daytime twice-a-day MODIS observations and hourly AHI observations. In section 2, the dataset and analyses are described. In section 3, co-occurring AHI and MODIS estimations of cloud cover over four months are validated by using accurate cloud detections from the Cloud-Aerosol LiDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation (CALIPSO) instrument. Then, the semidiurnal cycles of cloud cover on a monthly scale are evaluated by using different sampling intervals from AHI measurements. We summarize our conclusions in section 4.

Data and analytical methodology

We defined the TP region as the area from 26 to 40°N and from 73 to 105°E. The satellite datasets included the Himawari-8/AHI level-2 daily cloud mask, the Aqua MODIS Collection 6 level-2 daily cloud fractions and the CALIPSO level-2 daily vertical feature mask (VFM). The time periods considered for the AHI, MODIS and VFM data were April, July, and October of 2016 and January of 2017 to evaluate cloud detection in different seasons. Although all of the AHI, MODIS and VFM datasets include nighttime observations, only daytime data were analyzed here because the AHI nighttime cloud data had not been released at the time of writing.

The AHI cloud mask was evaluated by using a sequence of snow/ice, cloud and aerosol tests, including radiative transfer and temporal-uniformity calculations24,25,26,27. The AHI cloud mask was generated at a grid scale of 5 × km, and each grid was categorized into one of four categories: clear, probably clear, probably cloudy and cloudy. Both the probably cloudy and cloudy results were validated in this study. The investigation of diurnal cycles in cloud variation over the TP requires a spatial resolution of less than 7 km and a temporal resolution of less than 3 h28,29. In addition, the morning and evening products have incomplete coverage over the TP at solar zenith angles above 80°. Therefore, we examined only semidiurnal variations using AHI hourly cloud data that spanned 2:00–10:00 UTC.

The MODIS level-2 cloud fractions are available twice-a-day (daytime) over the TP at 10:30 and 13:30 local time from 2002 to the present at a grid scale of 5 × 5 km30. The cloud fraction is calculated from the level 2 cloud mask, which is determined from a large number of threshold tests and has a spatial resolution of 1 × 1 km30. The cloud fraction expresses the probability of cloud fraction within a grid from 0 to 100%19. For consistency with the AHI cloudy detections, we defined cloudy MODIS pixels as those with probabilities greater than 95%.

The VFM products provide an accurate vertical distribution of six feature types: clouds, aerosols, clear air, stratospheric features, surface, and subsurface31,32. LiDAR is much more sensitive to optically thin clouds than passive sensors; additionally, the cloud detection of CALIPSO is not affected by snow or ice cover33,34. The VFM data had a vertical and horizontal resolution of 180 m and 1667 m, respectively, at altitudes of approximately 20.2–30.1 km, a vertical and horizontal resolution of 30 m and 333 m, respectively, at altitudes of approximately 0–8.2 km, and a vertical and horizontal resolution of 60 m and 1000 m, respectively, at altitudes of 8.2–20.2 km33. The VFM products are based on version 3.30 (April, July, and October 2016) and 3.40 (January 2017). To match the AHI and MODIS cloud detection results, the horizontal resolution of VFM profiles were sampled to 5 km resolution from 0–30.1 km by using the center profile. In the process, only cloudy features with high- and middle- confidence were adopted; features with low confidence as well as those transparent and broken clouds (indicated by VFM cloud subtype) were discarded.

Both the CALIPSO and Aqua satellites are in the A-Train constellation, flying in close formation. Therefore, the cloud measurements from the two sensors were assumed here to be acquired at nearly the same time. CALIPSO passes the TP at approximately 7:00 UTC every day. Therefore, we obtained the AHI measurements at 7:00 UTC to correspond with the VFM results. Only the top cloud layer was considered when classifying a VFM pixel as cloudy or not. To quantitatively assess the accuracy of AHI’s and MODIS’s cloud detections, we used the false alarm rate (FAR) and Cloud Hit Rate (CHR) to evaluate performance. The FAR represents the fraction of clear pixels incorrectly classified as cloudy22, and the CHR represents the fraction of cloudy pixels in the dataset that are correctly classified35.

where \({\rm{MODIS}}|{{\rm{AHI}}}_{cloudy}\) is the number of cloudy pixels in the MODIS or AHI cloud detections, and \({{\rm{VFM}}}_{non-cloudy}\) and VFM cloudy are the number of non-cloudy and cloudy pixels, respectively. “&” indicates the pixels in agreement, and N is the total number of cloudy pixels detected by MODIS or AHI. According to the requirements of VIIRS cloud mask, the FAR for cloud discrimination should be within 8% in different surface types36. VIIRS cloud mask inherit from MODIS algorithm with many improvements. Therefore, we adopt the high-level criteria (FAR < 8%) to access the whether the performance of MODIS and VIIRS cloud discrimination is reliable over the TP.

Results

Generally, higher confidence-level cloud detections indicate a higher possibility of cloud occurrence and greater cloud coverage within the grid. First, we compared AHI’s cloudy and probably cloudy pixels with simultaneous LiDAR measurements over the TP. Figure 1(a) indicates that pixels that were designated cloudy in the AHI cloud mask better matched the LiDAR observations than did the probably pixels, with an average FAR value of 7.51%. The probably cloudy pixels of AHI had an average FAR value of 12.13%. Figure 1(b) shows the joint assessment of AHI’s and MODIS’s cloudy identifications over the TP. The figure shows that the AHI cloudy results show larger bias than the MODIS cloudy results. Numbers for comparison are presented in Table 1. The average FAR values for AHI and MODIS were 7.51% and 1.94%, respectively. For the months of April, June, October, and January, the average FAR values of cloudy pixels for AHI were 4.44%, 2.23%, 12.06% and 11.32%, respectively, and those for MODIS were 0.42%, 0.59%, 1.20% and 5.54%, respectively. As shown in Table 2, the average CHR values for AHI and MODIS were 73.55% and 80.15%, respectively. For the months of April, June, October, and January, the average CHR values of cloudy pixels for AHI were 70.14%, 75.29%, 76.74% and 72.03%, respectively, and those for MODIS were 84.41%, 81.32%, 67.18% and 87.67%, respectively.

These FAR and CHR results indicate that MODIS’s cloudy estimates more closely matched the LiDAR measurements, partially because we implemented a very strict threshold (cloud fraction >95%) when selecting cloudy pixels for MODIS. In comparison with the MODIS cloudy results, the AHI cloudy results were generated with a relatively less strict requirement. Moreover, MODIS observes the TP at a lower orbit and from a smaller satellite viewing angles above the TP. In comparison, AHI’s orbital heights are much higher than those of MODIS, and the TP is located at the edge of the full Earth disk image of the Himawari-8 satellites; thus, it has greater geometric deformation.

A daily comparison of cloudy pixels between MODIS and AHI in the four investigated months was conducted to evaluate their performance in cloud detection (Fig. 2). Both AHI and MODIS yielded more accurate cloud-cover estimates during the spring and summer than during the autumn and winter. For example, the average FAR for cloudy pixels from AHI was less than 5.00% during the spring and summer, whereas the values for the autumn and winter exceeded 11.00%. Investigation of cloud-detection bias for the dates of October 31, 2016, January 1, 2017, and January 11, 2017, showed erroneous detection of snow or ice cover as clouds for both the AHI and MODIS cloud-detection algorithms. The TP is bounded by the southern and western Himalayas, the eastern Hengduan Mountains and the northern Kunlun Mountains, which have elevations that exceed 5000 m and are dominated by glaciers, and ground snow and ice in these regions increase during the autumn and winter37,38. We concluded that the cloudy results of MODIS show greater agreement with the VFM results than did the AHI results. In addition, although AHI and MODIS provide measurements from different platforms, both are able to discriminate clouds over the TP with a FAR of no more than 8% based on comparisons with CALIOP.

Using hourly AHI cloudy results (UTC 2:00–10:00), a cloud cover frequency map was produced for each of April, June, October, and January (Fig. 3). Significant semidiurnal variability in cloud cover was recognized the over TP, especially in mountain areas. This phenomenon was likely caused by cumulus growth on the south-facing slopes, which were inclined towards the sun39. During April, the cloud fraction increased from morning to evening, especially along the eastern and southern borders of the TP. However, the semidiurnal cloud-cover cycle was weaker in July than in the other three months. July’s cloud cover over the TP was relatively high throughout the day due to the influence of monsoons40, especially in the southern and western-to-northern areas of the TP. Evidence of variation in cloud cover from morning to evening was apparent for April, October and January, with the mean cloud-cover frequency (MCCF) decreasing until UTC 4:00 and then increasing until UTC 10:00.

Average cloud cover from 2:00 to 10:00 UTC based on AHI data in (a) May, (b) July, (c) October 2016 and (d) January 2017. The twilight is defined with solar zenith angles of 85°~93°. Besides, the morning and evening products have incomplete coverage over the TP at solar zenith angles above 80°, therefore in October and January some regions are blank. The figures were generated using the software ArcGIS 10.1 (http://www.esrichina.com.cn).

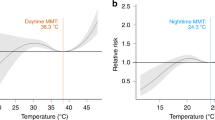

The second aim of this study was to identify the difference in MCCF between the polar-orbiting and geostationary satellites. MCCF is the sum of all cloud-cover frequency values divided by the number of pixels and was used to express the hourly cloud occurrences for each month. AHI and MODIS acquire similar observations but at different temporal resolutions. MODIS observes the TP almost four times a day, including the daylight portions of the UTC 04 and UTC 07 orbits. We compared the MCCF values derived from twice-a-day (MODIS-time) observations with those derived from hourly AHI observations. In the calculation, we used AHI cloud detections at UTC 4:00 and UTC 7:00 as surrogates for Terra and Aqua MODIS measurements to minimize the uncertainties associated with their cloud detection results. As depicted in Fig. 4, in January, April and October, the AHI MCCF values (black line) decreased from UTC 2:00–4:00 (local time, 8:00–10:00 a.m. and then increased until UTC 10:00 (local time, 18:00 p.m.). However, in July, the values remained stable before 12:00 a.m., with few oscillations, and increased thereafter. Similar to previous studies, in the present study, upper-tropospheric cirrus clouds that originated from deep convection in mountainous areas showed maxima close to sunset41. Furthermore, smaller semidiurnal cycles of cloud variation occurred in July and October, 2016, because the cloud cover in these two months continued to exhibit high values.

MCCF values for AHI hourly cloud cover over the TP in April, July, and October 2016 and January 2017. AHI cloud detections at UTC 4:00 and UTC 7:00 were used as Terra/MODIS and Aqua/MODIS measurements. The average FAR values for the AHI and MODIS-time measurements are displayed as black and red dashed lines, respectively.

Based on the validations, we assume that the Terra/MODIS and Aqua/MODIS observations can be represented adequately by the AHI cloud mask. We recalculated MODIS’s average cloud fraction by using the AHI cloud mask, which corresponds in time with the MODIS observations at UTC 4:00 and UTC 7:00, to examine the uncertainties that were associated with MODIS’s monthly daytime average cloud fraction without considering the semidiurnal cycle of cloud variability. Additionally, we calculated the true average cloud fraction based on the 9-h AHI cloud mask results. The black and red dashed lines in Fig. 4 represent the averaged AHI 9-h (UCT 2:00–10:00) MCCF values and averaged MODIS-time (UCT 4:00 and UTC 7:00) MCCF values, respectively. The averaged AHI MCCF values are larger than the averaged MODIS-time MCCF values in all four months. This finding indicates that if the MODIS-time cloud cover was used to calculate the monthly average daytime MCCF over the TP, the results would underestimate the MCCF because of the absence of semidiurnal cloud variation. Table 3 presents the differences between the averaged AHI 9-h and MODIS-time MCCF values. MODIS underestimated the monthly average daytime MCCF by 5.40%, 1.48%, 3.21%, and 5.90% in April, July, and October of 2016 and January of 2017, respectively. The average underestimation over these four months was 4.00%.

The validation is limited in the following several aspects: 1) The MODIS and AHI cloud detections were validated against the VFM cloud detections. The VFM measurements are taken in orbit and cannot provide validation over large-area regions. 2) The horizontal resolution of the VFM data at three different elevations ranged from 333 m to 1667 m. We sampled the VFM data to a horizontal resolution of 5 km using only the center profile, which might have introduced bias into the resampled VFM result. 3) Multiple MODIS images are necessary to encompass the TP on any given day due to its more limited spatial coverage, which means that the cloud fields over TP are not imaged at the same time. Therefore, in the analysis of the MODIS-estimated and AHI-estimated MCCF values, we used AHI cloud detections at UTC 4:00 and UTC 7:00 to substitute Terra/MODIS and Aqua/MODIS measurements, which may differ from the MODIS measurements.

Concluding remarks

In this study, cloud discrimination over the Tibetan Plateau is analyzed by the MODIS and AHI sensors. This study investigated the accuracy of AHI and MODIS cloud detections and evaluated the semidiurnal variation of cloud cover as derived from AHI high temporal-resolution observations. Treating the CALIPSO measurements as the truth data, our analysis of AHI and MODIS cloud detections over the TP along the CALIPSO track yielded FARs of 7.51% and 1.94%, respectively, and CHRs of 73.55% and 80.15%, respectively. The results indicate that AHI and MODIS cloud detections are reliable over the TP. We also compared diurnal cycles in the total cloud coverage in each season to investigate the estimated cloud-cover frequency from polar-orbiting and geostationary satellites. Similar trends in cloud-cover distributions occurred during all seasons, with minimum and maximum cloud-cover frequencies at 4:00 and 10:00 UTC, respectively. Due to the limit in temporal resolution, MODIS-time monthly average cloud-cover data underestimated the total cloud cover by approximately 4.00% on an annual basis. This tendency towards underestimation was greatest during the spring and winter. The temporal resolution of satellite-observed cloud climatology should be considered depending on the application.

Several unresolved issues remain. First, a more comprehensive understanding of the cloud-mask result difference of MODIS and AHI is required. Resolving this problem requires investigating instrument characteristics, algorithms and orbits. Second, a time-resolution threshold above which the average daily or monthly cloud-cover can be considered reliable may be created for regional and global cloud climatology studies. Finally, analysis of cloud property differences between sensors is an ongoing concern between the operational cloud retrieval groups42,43, AHI cloud mask, optical and microphysical properties estimated from CLAUDIA44 and CAPCOM45 algorithms. A comprehensive validation of AHI cloud properties on near-global scales is still needed. If AHI cloud optical and microphysical properties are accurate with polar-orbiting satellites, Himawari-8 cloud retrievals may be used in analyzing the uncertainties that are associated with the limited temporal resolution of polar-orbiting instruments in cloud variables such as the optical cloud thickness and effective radii.

Permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Che, H. Z. et al. Analysis of 40 years of solar radiation data from China, 1961–2000. Geophysical Research Letters 32, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004gl022322 (2005).

Fluteau, F., Ramstein, G. & Besse, J. Simulating the evolution of the Asian and African monsoons during the past 30 Myr using an atmospheric general circulation model. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 104, 11995–12018 (1999).

Ruddiman, W. & Kutzbach, J. Forcing of late Cenozoic northern hemisphere climate by plateau uplift in southern Asia and the American West. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 94, 18409–18427 (1989).

Guo, J. et al. The climatology of planetary boundary layer height in China derived from radiosonde and reanalysis data. Atmos. Chem. Phys 16, 13,309–313,319 (2016).

Gao, B. C. et al. Measurements of water vapor and high clouds over the Tibetan Plateau with the Terra MODIS instrument. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 41, 895–900, https://doi.org/10.1109/tgrs.2003.810704 (2003).

Yanai, M. H., Li, C. F. & Song, Z. S. Seasonal heating of the Tibetan Plateau and its effects on the evolution of the summer monsoon. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan 70, 319–351 (1992).

Gautam, R. et al. Accumulation of aerosols over the Indo-Gangetic plains and southern slopes of the Himalayas: distribution, properties and radiative effects during the 2009 pre-monsoon season. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 11, 12841–12863, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-12841-2011 (2011).

Duan, A. M. & Wu, G. X. Change of cloud amount and the climate warming on the Tibetan Plateau. Geophysical Research Letters 33, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006gl027946 (2006).

Sato, T., Miura, H. & Satoh, M. Spring diurnal cycle of clouds over Tibetan Plateau: Global cloud-resolving simulations and satellite observations. Geophysical Research Letters 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007gl030782 (2007).

Duan, J. P., Li, L. & Fang, Y. J. Seasonal spatial heterogeneity of warming rates on the Tibetan Plateau over the past 30 years. Scientific Reports 5, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11725 (2015).

Pinker, R., Zhang, B. & Dutton, E. Do satellites detect trends in surface solar radiation? Science 308, 850–854 (2005).

Wonsick, M. M., Pinker, R. T. & Govaerts, Y. Cloud Variability over the Indian Monsoon Region as Observed from Satellites. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 48, 1803–1821, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009jamc2027.1 (2009).

Ruthrich, F., Thies, B., Reudenbach, C. & Bendix, J. Cloud detection and analysis on the Tibetan Plateau using Meteosat and CloudSat. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres 118, 10082–10099, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50790 (2013).

Nakajima, T. Y., Tsuchiya, T., Ishida, H., Matsui, T. N. & Shimoda, H. Cloud detection performance of spaceborne visible-to-infrared multispectral imagers. Applied Optics 50, 2601–2616, https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.50.002601 (2011).

Fujinami, H. & Yasunari, T. Submonthly variability of convection and circulation over and around the Tibetan Plateau during the boreal summer. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan 82, 1545–1564, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.82.1545 (2004).

Li, Y. Q., Liu, X. D. & Chen, B. D. Cloud type climatology over the Tibetan Plateau: A comparison of ISCCP and MODIS/TERRA measurements with surface observations. Geophysical Research Letters 33, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006gl026890 (2006).

Rossow, W. B. & Schiffer, R. A. Advances in understanding clouds from ISCCP. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 80, 2261–2287 (1999).

Pincus, R., Platnick, S., Ackerman, S. A., Hemler, R. S. & Hofmann, R. J. P. Reconciling Simulated and Observed Views of Clouds: MODIS, ISCCP, and the Limits of Instrument Simulators. Journal of Climate 25, 4699–4720, https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-11-00267.1 (2012).

Ackerman, S. A. et al. Discriminating clear sky from clouds with MODIS. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres 103, 32141–32157, https://doi.org/10.1029/1998jd200032 (1998).

Bessho, K. et al. An Introduction to Himawari-8/9 Japan’s New-Generation Geostationary Meteorological Satellites. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan. Ser. II 94, 151–183, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2016-009 (2016).

Naud, C. M. & Chen, Y.-H. Assessment of ISCCP cloudiness over the Tibetan Plateau using CloudSat-CALIPSO. Journal of Geophysical Research 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009jd013053 (2010).

Hutchison, K. D., Iisager, B. D. & Hauss, B. The use of global synthetic data for pre-launch tuning of the VIIRS cloud mask algorithm. International Journal of Remote Sensing 33, 1400–1423, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2011.571299 (2012).

Shang, H. et al. Development of a daytime cloud and haze detection algorithm for Himawari-8 satellite measurements over central and eastern China. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016jd025659 (2017).

Imai, T. & Yoshida, R. Algorithm theoretical basis for Himawari-8 Cloud Mask Product. Meteorol. Satell. Center Tech. Note 61, 1–17 (2016).

Matsumoto, H. Research on solar power satellites and microwave power transmission in Japan. Microwave Magazine, IEEE 3, 36–45 (2002).

Ishida, H. & Nakajima, T. Y. Development of an unbiased cloud detection algorithm for a spaceborne multispectral imager. Journal of Geophysical Research 114, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008jd010710 (2009).

Letu, H., Nagao, T. M., Nakajima, T. Y. & Matsumae, Y. Method for validating cloud mask obtained from satellite measurements using ground-based sky camera. Appl Opt 53, 7523–7533, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.53.007523 (2014).

Joyce, R. J., Janowiak, J. E., Arkin, P. A. & Xie, P. CMORPH: A method that produces global precipitation estimates from passive microwave and infrared data at high spatial and temporal resolution. Journal of Hydrometeorology 5, 487–503 (2004).

Sato, T., Yoshikane, T., Satoh, M., Miltra, H. & Fujinami, H. Resolution Dependency of the Diurnal Cycle of Convective Clouds over the Tibetan Plateau in a Mesoscale Model. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan 86A, 17–31 (2008).

Frey, R. A. et al. Cloud detection with MODIS. Part I: improvements in the MODIS cloud mask for collection 5. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 25, 1057–1072, https://doi.org/10.1175/2008jtecha1052.1 (2008).

Hagihara, Y., Okamoto, H. & Yoshida, R. Development of a combined CloudSat-CALIPSO cloud mask to show global cloud distribution. Journal of Geophysical Research 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009jd012344 (2010).

Winker, D. M. et al. Overview of the CALIPSO mission and CALIOP data processing algorithms. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 26, 2310–2323, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009jtecha1281.1 (2009).

Chan, M. A. & Comiso, J. C. Cloud features detected by MODIS but not by CloudSat and CALIOP. Geophysical Research Letters 38, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011gl050063 (2011).

Delanoe, J. & Hogan, R. J. Combined CloudSat-CALIPSO-MODIS retrievals of the properties of ice clouds. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009jd012346 (2010).

Mace, G. G., Jakob, C. & Moran, K. P. Validation of hydrometeor occurrence predicted by the ECMWF Model using millimeter wave radar data. Geophysical Research Letters 25, 1645–1648, https://doi.org/10.1029/98GL00845 (1998).

Kopp, T. J. et al. The VIIRS Cloud Mask: Progress in the first year of S-NPP toward a common cloud detection scheme. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 119, 2441–2456, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jd020458 (2014).

Cui, X. & Graf, H.-F. Recent land cover changes on the Tibetan Plateau: a review. Clim. Change 94, 47–61, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-009-9556-8 (2009).

Devasthale, A. & Fueglistaler, S. A climatological perspective of deep convection penetrating the TTL during the Indian summer monsoon from the AVHRR and MODIS instruments. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 10, 4573–4582, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-4573-2010 (2010).

Wylie, D. P. Diurnal Cycles of Clouds and How They Affect Polar-Orbiting Satellite Data. Journal of Climate 21, 3989–3996 (2008).

Yan, Y. F., Liu, Y. M. & Lu, J. H. Cloud vertical structure, precipitation, and cloud radiative effects over Tibetan Plateau and its neighboring regions. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres 121, 5864–5877, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015jd024591 (2016).

Wylie, D. P. & Woolf, H. M. The Diurnal Cycle of Upper-Tropospheric Clouds Measured by GOES-VAS and the ISCCP. Monthly Weather Review 130, 171–179 (2002).

Hamann, U. et al. Remote sensing of cloud top pressure/height from SEVIRI: analysis of ten current retrieval algorithms. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 7, 2839–2867 (2014).

Wu, D. L. et al. Towards Global Harmonization of Derived Cloud Products. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (2017).

Ishida, H., Nakajima, T. Y. & Letu, H. Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document of the CLAUDIA for GCOM/SLGI cloud screening. JAXA EORC (2011).

Nakajima, T. Y. & Letu, H. Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document of CAPCOM for GCOM/SLGI. JAXA EORC (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 4177011812) and National Natural Science Foundation for Youth Science Funds of China (Grant No. 10010108B1339-2451), the CAS Pioneer Hundred Talents Program, the China High-Resolution Earth Observation Projects (30-Y20A20-9003-15/17 and 32-Y20A17-9001-15-17-2), the International Partnership Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (131C11KYSB20160061). The authors are grateful to Meng Zhao from University of California at Irvine for useful discussions. Research product of cloud mask from Himawari-8 that was used in this paper’ was supplied by the P-Tree System, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). We also thank NASA for making the MODIS, CALIPSO and Himawari-8 data readily available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z.S. designed the research and wrote the main text, H.S.L.T. prepared the Himawari-8 data and wrote the cover letter and abstract, T.Y.N. provided detailed information on the Himawari-8 cloud algorithm, Z.M.W. downloaded the CALIPSO data and analyzed the Himawari-8 data, R.M. developed the code to interpret the MODIS cloud products, T.X.W. edited the manuscript for language issues, Y.H.L. contributed to the structure of the study, D.B.J. plotted Figs 1–2, S.S.L. calculated the FAR and CHR values and J.C.S. funded the research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shang, H., Letu, H., Nakajima, T.Y. et al. Diurnal cycle and seasonal variation of cloud cover over the Tibetan Plateau as determined from Himawari-8 new-generation geostationary satellite data. Sci Rep 8, 1105 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19431-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19431-w

This article is cited by

-

Effects of the Indian summer monsoon on the cloud characteristics over the Eastern Tibetan Plateau: a simulation study

Climate Dynamics (2024)

-

Radiative contributions of different cloud types to regional energy budget over the SACOL site

Climate Dynamics (2023)

-

Spatiotemporal Variations of Microwave Land Surface Emissivity (MLSE) over China Derived from Four-Year Recalibrated Fengyun 3B MWRI Data

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2022)

-

Interannual shift of tropical high cloud diurnal cycle under global warming

Climate Dynamics (2022)

-

The semi-diurnal cycle of deep convective systems over Eastern China and its surrounding seas in summer based on an automatic tracking algorithm

Climate Dynamics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.