Abstract

Using a non-targeted metabolomics platform, we recently identified C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine as non-traditional kidney function markers. The aims of this study were to obtain absolute concentrations of both metabolites in blood and urine from individuals with and without CKD to provide reference ranges and to assess their fractional excretions (FE), and to assess the agreement with their non-targeted counterparts. In individuals without/with CKD, mean plasma and urine concentrations for C-mannosyltryptophan were 0.26/0.72 µmol/L and 3.39/4.30 µmol/mmol creatinine, respectively. The respective concentrations for pseudouridine were 2.89/5.67 µmol/L and 39.7/33.9 µmol/mmol creatinine. Median (25th, 75th percentiles) FEs were 70.8% (65.6%, 77.8%) for C-mannosyltryptophan and 76.0% (68.6%, 82.4%) for pseudouridine, indicating partial net reabsorption. Association analyses validated reported associations between single metabolites and eGFR. Targeted measurements of both metabolites agreed well with the non-targeted measurements, especially in urine. Agreement for composite nephrological measures FE and urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio was lower, but could be improved by replacing non-targeted creatinine measurements with a standard clinical creatinine test. In summary, targeted quantification and additional characterization in relevant populations are necessary steps in the translation of non-traditional biomarkers in nephrology from non-targeted discovery to clinical application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major public health concern affecting approximately 10% of the population1. It is defined based on measures of kidney damage and kidney function. To assess kidney function, metabolites such as creatinine and urea are measured in blood and used to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR)2,3. Currently used markers of kidney function, however, have limitations. For example, plasma creatinine concentrations only exceed the normal range when more than 50% of kidney function has been lost and also depend on age, sex and race as proxies of muscle mass4. The identification of additional kidney function markers is therefore of clinical importance in the diagnosis, staging and monitoring of CKD.

Recently, we conducted a study in population-based cohorts using a non-targeted metabolomics approach for metabolite quantification to discover and replicate serum metabolites that may be useful kidney function markers beyond creatinine5. We identified C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine as strong correlates of estimated and measured GFR. Our study confirmed previous findings using similar non-targeted approaches6,7 and showed that, in contrast to serum creatinine, these potential alternative or complementary markers of kidney function showed little dependency on sex.

While non-targeted metabolomics methods have the advantage of detecting a broad spectrum of metabolites from different metabolic pathways, including metabolites of yet unknown identity8, they do not necessarily deliver absolute and accurate metabolite concentrations. This complicates the comparison of metabolite levels across populations and across the two biofluids of primary interest in nephrology, namely blood and urine. In our previous project, C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine were identified based on non-targeted gas and liquid chromatography coupled to (nominal mass) mass spectrometry (GC/MS, LC/MS). Actual molar concentration ranges of C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine in blood and urine, as well as their fractional excretions (FE), were not described.

On the way to clinical implementation, however, detailed knowledge about these two non-traditional markers in both healthy individuals and CKD patients is important. The first aim of the current study was to fill this gap by using a targeted approach to quantify C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine employing liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry in combination with stable isotope-labeled internal standards. The second aim was to systematically evaluate the agreement of non-targeted semi-quantitative and targeted absolute measurements for the two markers with special emphasis on composite measures of nephrological interest, the urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio and the FE. A schematic presentation of the project is provided in Fig. 1.

Results

Concentrations and fractional excretion of C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine

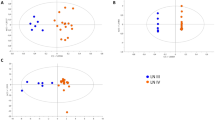

Targeted measurements of C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine were obtained for 111 control participants without diabetes and CKD from the QMDiab Study and for 382 CKD patients selected from the GCKD study (Table 1).

In the healthy QMDiab individuals, mean C-mannosyltryptophan concentrations were 0.26 µmol/L (SD: 0.05) in plasma and 3.39 µmol/mmol creatinine (SD: 0.80) in urine. Mean pseudouridine concentrations were 2.89 µmol/L (SD: 0.52) in plasma and 39.7 µmol/mmol creatinine (SD: 6.74) in urine (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The FE is an informative measure for kidney filtration markers, as it allows the assessment of a substance’s net secretion into urine or net reabsorption into the blood. The median (25th, 75th percentiles) of the FE were 76.0% (68.6%, 82.4%) for pseudouridine and 70.8% (65.6%, 77.8%) for C-mannosyltryptophan, suggesting partial net reabsorption for both metabolites. Graphical illustration of the distributions of the plasma and urine concentrations of both markers as well as their FEs showed that a natural logarithmic transformation was appropriate in most cases to reduce skewness (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In CKD patients, the mean plasma concentrations of C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine were clearly higher than in the QMDiab controls (Table 2 and Fig. 2). In urine, mean absolute concentrations of both metabolites were lower in CKD patients than in healthy controls. When accounting for urine dilution, mean concentrations of C-mannosyltryptophan in urine were higher among CKD patients than controls, but lower for pseudouridine. While the shape of the metabolites’ distributions did not differ markedly between the two cohorts (Supplementary Fig. S1), the plasma concentrations and FEs had a wider range in CKD patients (Table 2).

In the healthy QMDiab individuals, we observed a strong positive correlation between the concentrations of the two metabolites within a given biofluid (Spearman correlation coefficient [SCC]: plasma 0.74, urine 0.81), while the correlations between biofluids were weak to moderate (SCC comparing plasma to urine: C-mannosyltryptophan 0.40, pseudouridine 0.20). Similar results were obtained in CKD patients (Table 3). Table 3 also shows correlations between targeted metabolite measurements in CKD patients and different established clinical laboratory measurements of kidney function markers, including a creatinine test that currently represents the clinical standard for the measurement of creatinine. For creatinine in blood, the SCC of targeted mass spectrometry-based plasma measurements and serum standard laboratory measurements was 0.96, showing excellent correlation. The same held true for urine (SCC: 0.96, Supplementary Fig. S2).

Furthermore, we evaluated the associations of C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine with eGFR5 using absolute metabolite concentrations to provide estimated changes in eGFR per unit change of metabolite on an interpretable scale. Models including one of the metabolites showed highly significant associations (Supplementary Table S1 and S2). When including both metabolites at the same time, however, only association with pseudouridine remained significant.

Comparison of non-targeted and targeted measurements

The choice of the QMDiab study for this project allowed us to evaluate the important question whether data from non-targeted measurements are suitable to calculate composite measures used in nephrology, the urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio and the metabolite’s FE. The latter is of particular interest, because its calculation requires both serum (plasma) and urine concentrations of creatinine and the metabolite of interest, for which measurements that are not generated using an isotope-labeled standard may not be comparable. We therefore used data from the 110 QMDiab individuals, for whom both targeted and non-targeted measurements were available, to address this second aim.

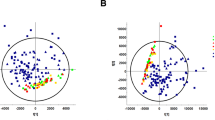

For pseudouridine, targeted and non-targeted measurements in plasma correlated well (SCC: 0.67) and even better in urine (SCC:0.90, Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained for creatinine (Fig. 3B). However, agreements weakened when combining these measurements into the urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio or the FE (Fig. 3C,D). The SCC for the FE of pseudouridine, for example, was only 0.32.

Comparison of ranks of targeted and non-targeted mass spectrometric measurements of pseudouridine and creatinine as well as respective composite measures of pseudouridine in individuals without CKD. (A) Pseudouridine, (B) Creatinine, (C) Urinary pseudouridine-to-creatinine ratio, (D) Fractional excretion – original version: using creatinine measurements from respective platform, i.e. targeted or non-targeted, (E) Fractional excretion – adapted version: using standard clinical laboratory measurement of creatinine. SCC: Spearman correlation coefficient corresponding to slope of displayed regression line of rank-transformed measurements.

Since creatinine is used both for accounting for urine dilution by calculating the urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio as well as in the calculation of FE, accurate quantification of creatinine is of particular importance. We thus investigated correlations with creatinine from a standard clinical laboratory test and found very good agreement with all other measurements of creatinine (SCC:>0.9, Supplementary Fig. S3), except for the non-targeted, nominal mass platform-based measurement of creatinine in plasma (SCC:0.67). We therefore examined whether the use of standard clinical creatinine in the estimation of the FEs would improve the agreement. Indeed, correlations for the FE of pseudouridine improved (SCC: from 0.32 to 0.68, Fig. 3E), suggesting that substitution of non-targeted creatinine with standard clinical creatinine for the calculation of FEs for metabolites can be appropriate when a standard creatinine test is available. Similar observations were also made for C-mannosyltryptophan (Supplementary Fig. S4 ).

Although such an approach might be useful, creatinine values from a standard clinical test may not always be available in population studies. While there is no non-creatinine alternative for the calculation of the FE, there are alternatives other than the urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio to correct urine metabolite concentrations for dilution. Firstly, osmolality can be quantified as part of a metabolomics study and can be used for this purpose. Secondly, when a larger number of metabolites are quantified simultaneously, individual dilution factors can be deduced using a probabilistic approach, called probabilistic quotient (PQ) normalization9. These alternative measures of urine dilution showed good correlation with urinary creatinine from the clinical assay (Supplementary Fig. S5). Thus, osmolality or PQ-normalization might be used to derive dilution-corrected concentrations of metabolites in urine when creatinine from a standard clinical test is not available.

Discussion

The validation and characterization of non-traditional biomarkers in healthy and diseased individuals is a challenging but necessary step on the way to their clinical use. Our study reports absolute blood plasma and urine concentrations of both C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine5 in individuals with and without CKD. Capitalizing on the absolute quantification of pseudouridine and C-mannosyltryptophan in both plasma and urine, our results provide evidence for net re-absorption of both metabolites during tubular passage.

Our study extends findings from previous studies in several ways: first, previous metabolomics studies in nephrology often carried out global screens based on non-targeted metabolite quantification and/or used targeted methods that did not contain isotope-labeled internal standards for all of the metabolites5,6,7,10,11,12,13. Here, we specifically focused on two non-traditional kidney function marker candidates that were measured using a targeted technique with isotope-labeled internal standards. Secondly, previous studies of pseudouridine and C-mannosyltryptophan have evaluated their concentrations in blood or urine14,15,16,17, but they had not compared their concentration ranges in individuals with and without CKD. In addition, the absolute quantification of these kidney function markers in both blood and urine minimizes the influence of matrix effects that can affect the calculation of FE.

The FE of a metabolite is an important measure when searching for renal filtration markers based on comparison with the clearance of exogenous kidney function markers such as inulin. In this setting, an ideal filtration marker should be produced at a constant rate and show neither evidence for net secretion nor reabsorption, i.e., a FE of 100%. Pseudouridine is a modified nucleoside originating from RNA catabolism18. Because of its constant production and excretion as well as its free filtration, it has been evaluated as an endogenous renal filtration marker as early as the 1980’s14. However, it had been dismissed as a filtration marker because of its partial net reabsorption, consistent with our and other estimates15. C-mannosyltryptophan results from N-glycosylation, a post-translational modification, of tryptophan19. Takahira and colleagues showed that C-mannosyltryptophan reflected inulin clearance much better than creatinine clearance did16. They concluded that C-mannosyltryptophan might be suited to replace inulin as a renal function marker, consistent with other reports demonstrating the superiority of C-mannosyltryptophan as a renal function marker as compared to creatinine17. In our study, the FE of C-mannosyltryptophan was 71% in individuals without CKD, similar to that observed for pseudouridine. Together with our previous study showing a high correlation of pseudouridine and C-mannosyltryptophan with measured GFR5, these results suggest that an FE close to 100% is not a prerequisite for a filtration marker. Future complementary filtration markers are likely to be identified in an agnostic manner similar to the one used in our previous study5.

While the targeted measurements of C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine in this study generally agreed well with the initial non-targeted measurements, agreement for the FE and the urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio, composite metabolite measures in nephrology, was lower. Potential explanations are the combined effects of the less than accurate mass spectrometric determination of analytes in the absence of stable isotope-labeled internal standards to correct for differences in the composition of biological matrices that may affect the ionization of the compounds of interest. This most likely explains the higher FE values reported by Solini et al. based on their non-targeted quantification of pseudouridine and C-mannosyltryptophan7. Although our data suggest that the FE should not be calculated using non-targeted measurements of C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine, this might not be true for all metabolites and could change with future improvements of measurement platforms.

Previous studies have also compared the agreement between non-targeted and targeted mass spectrometric measurements of metabolites20,21,22,23,24,25. Yet et al., for instance, compared two of the most frequently used mass spectrometry based metabolomics platforms, the non-targeted Metabolon platform and the Biocrates platform, which uses stable isotope-labeled internal standard for some but not all of its metabolites25. The authors found that correlations between metabolites quantified on both platforms varied largely, highlighting that general assumptions about agreements across metabolomics platforms are difficult. Overall, as in transcriptomics and proteomics studies, biomarkers discovered by non-targeted metabolomics methods should be validated prior to their clinical translation, by means of proper targeted methods that allow their accurate and, preferentially, absolute determination.

While this project provides valuable information on C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine, some potential limitations warrant mention: metabolite concentrations determined for control participants of the Qatari QMDiab study may not be globally representative. However, the generally higher concentrations in CKD patients are in line with our previous study examining these differences in a European sample, supporting generalizability at least within ethnic groups5.

In summary, accurate quantification of non-traditional biomarkers and their additional characterization in different population samples and biofluids are necessary steps prior to their potential clinical application.

Methods

Study populations

QMDiab study

The Qatar Metabolomics Study on Diabetes (QMDiab) was conducted in 2012 at the Dermatology Department of Hamad Medical Corporation in collaboration with the Weill Cornell Medical College in Doha, Qatar. This cross-sectional type 2 diabetes case-control study enrolled 374 participants of Arabic, South Asian, Filipino and other ancestry as described previously26. The QMDiab study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) and Weill and Cornell Medicine – Qatar (WCM-Q) under Research Protocol number 11131/11 and conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. After obtaining written informed consent from participants, samples of non-fasting plasma and spot urine were collected, put on dry ice for transport, processed and aliquoted using a standardized protocol and stored at −80 °C within 6 hours26. They were not thawed prior to metabolite measurements.

GCKD study

The German Chronic Kidney Disease (GCKD) study is a prospective cohort study of patients with CKD treated by nephrologists. It was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Erlangen (data coordinating center) and all other participating regional centers (Aachen, Berlin, Freiburg, Hannover, Heidelberg, Jena, Munich, Würzburg). The study was registered in the national registry for clinical studies (DRKS 00003971) and carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Between 2010 and 2012, 5,217 eligible adult patients provided written consent and were enrolled into the study27. All patients had CKD defined as eGFR of 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or either urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) > 300 mg/g or a protein-to-creatinine ratio >500 mg/g when eGFR was >60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Trained personnel obtained information; blood and spot urine were collected and immediately processed within a maximum of two hours (most within 30 minutes). They were shipped on dry ice on the same day to a central laboratory for routine clinical chemistry and to the study’s central biobank where they were immediately stored at −80 °C for future analyses28. Samples used in this study were thawed a maximum of two times prior to metabolite measurements. A complete description of the study design and the recruited study population can be found elsewhere27,29.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the parent studies, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Steering Committees of the parent studies.

Measurements

In this project, non-targeted and targeted mass spectrometric measurements of C-mannosyltryptophan, pseudouridine and creatinine in plasma and urine were obtained. A comprehensive description can be found in Supplementary Methods S1. Here, briefly: specimens of all QMDiab participants were sent to Metabolon Inc. (Durham, NC) for non-targeted quantifications using GC/MS and LC/MS in July 201226. All targeted quantifications were carried out by high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC/QQQMS) in the presence of the respective stable isotope-labeled internal standards at the Institute of Functional Genomics in Regensburg.

All measurements underwent stringent quality control. After cleaning, targeted measurements (µmol/L) were available from 111 consenting control participants in QMDiab (i.e. non-diabetic), who did not have CKD, and from a random sample of 382 CKD patients enrolled in the GCKD study. Paired measurements for both plasma and urine were obtained from all assessed control participants and 329 CKD patients. Non-targeted measurements (ion count) were available for 110 of the 111 non-CKD individuals of QMDiab with targeted measurements. Overall, the final datasets were rather complete with respect to measurements (<1% missing values per analyte and study).

Moreover, measurements of creatinine in blood (QMDiab: plasma, GCKD: serum) and urine using standard clinical laboratory methods were available. Serum cystatin C and urinary albumin were also available from CKD patients and osmolality from non-CKD individuals. GFR was estimated using the creatinine- or cystatin C-based Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula2,3, and UACR (mg/g) was derived from respective urinary measurements of albumin and creatinine.

Statistical analyses

The study sizes of the two study populations (non-CKD cohort: N = 111, CKD cohort: N = 382) were sufficient to describe the distribution and variability of the two continuous metabolites, C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine in plasma and in urine (unit: µmol/L) as well as their fractional excretions (FE, unit: %). Urinary measurements were standardized to creatinine measured from the respective platform (urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio, unit: µmol/mmol creatinine). Fractional excretion was calculated for each metabolite as

Numeric and graphical (boxplot, density plot) presentations were used to describe the distributions of single metabolites and FEs. Correlations between two single numerical measurements were quantified using Spearman correlation coefficient (SCC).

Multivariable linear regression was utilized to assess the associations between measured metabolites in plasma and urine (independent variables) with both creatinine-based eGFR and cystatin C-based eGFR (dependent variables) in CKD patients. Three types of models were considered: (A) models including C-mannosyltryptophan, (B) models including pseudouridine, and (C) models including both C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine. For each type and outcome, models adjusting for an increasing number of covariates were fitted: (1) no further adjustment, (2) adjusted for age and sex, and (3) adjusted for age, sex and 8 additional variables known to be associated with CKD: history of coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, anti-hypertensive medication use, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, C-reactive protein, high-density lipoprotein and triglycerides. All continuous variables (outcomes, metabolites, covariates) except age were log-transformed for association analyses. Only individuals with complete information were used for association analysis (N = 317, 96%).

The targeted and non-targeted measurements of C-mannosyltryptophan and pseudouridine were compared in the QMDiab study, with special emphasis on the urinary metabolite-to-creatinine ratio and the FE. For each metabolite measured on different platforms within a specific matrix, SCCs were calculated, linear regression models were fitted and data were graphically presented in scatter plots. Bland-Altman plots were used to assess systematic differences in agreement30. Following a non-parametric approach to obtain more robust findings, comparisons were performed using ranks of measurements. In contrast, creatinine measurements (standard clinical laboratory test, targeted and non-targeted quantification) were compared based on original scales, the unit used in routine clinical tests.

R software (version 3.2.3, www.r-project.org; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for statistical analyses.

References

Eckardt, K. U. et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet 382, 158–69 (2013).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150, 604–12 (2009).

Inker, L. A. et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 367, 20–9 (2012).

Stevens, L. A., Coresh, J., Greene, T. & Levey, A. S. Assessing kidney function–measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med 354, 2473–83 (2006).

Sekula, P. et al. A Metabolome-Wide Association Study of Kidney Function and Disease in the General Population. J Am Soc Nephrol 27, 1175–88 (2016).

Niewczas, M. A. et al. Uremic solutes and risk of end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes: metabolomic study. Kidney Int 85, 1214–24 (2014).

Solini, A. et al. Prediction of Declining Renal Function and Albuminuria in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes by Metabolomics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101, 696–704 (2016).

Adamski, J. & Suhre, K. Metabolomics platforms for genome wide association studies–linking the genome to the metabolome. Curr Opin Biotechnol 24, 39–47 (2013).

Dieterle, F., Ross, A., Schlotterbeck, G. & Senn, H. Probabilistic quotient normalization as robust method to account for dilution of complex biological mixtures. Application in 1H NMR metabonomics. Anal Chem 78, 4281–90 (2006).

Goek, O. N. et al. Serum metabolite concentrations and decreased GFR in the general population. Am J Kidney Dis 60, 197–206 (2012).

Goek, O. N. et al. Metabolites associate with kidney function decline and incident chronic kidney disease in the general population. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28, 2131–8 (2013).

Rhee, E. P. et al. A combined epidemiologic and metabolomic approach improves CKD prediction. J Am Soc Nephrol 24, 1330–8 (2013).

Rhee, E. P. et al. Metabolomics of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: A Case-Control Analysis in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study. Am J Nephrol 43, 366–74 (2016).

Bernert, J. T. Jr., Bell, C. J., Guntupalli, J. & Hannon, W. H. Pseudouridine is unsuitable as an endogenous renal clearance marker. Clin Chem 34, 1011–7 (1988).

Dzurik, R., Lajdova, I., Spustova, V. & Opatrny, K. Jr. Pseudouridine excretion in healthy subjects and its accumulation in renal failure. Nephron 61, 64–7 (1992).

Takahira, R. et al. Tryptophan glycoconjugate as a novel marker of renal function. Am J Med 110, 192–7 (2001).

Yonemura, K., Takahira, R., Yonekawa, O., Wada, N. & Hishida, A. The diagnostic value of serum concentrations of 2-(alpha-mannopyranosyl)-L-tryptophan for normal renal function. Kidney Int 65, 1395–9 (2004).

Colonna, A., Russo, T., Esposito, F., Salvatore, F. & Cimino, F. Determination of pseudouridine and other nucleosides in human blood serum by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem 130, 19–26 (1983).

Gutsche, B., Grun, C., Scheutzow, D. & Herderich, M. Tryptophan glycoconjugates in food and human urine. Biochem J 343(Pt 1), 11–9 (1999).

Suhre, K. et al. Metabolic footprint of diabetes: a multiplatform metabolomics study in an epidemiological setting. PLoS One 5, e13953 (2010).

Psychogios, N. et al. The human serum metabolome. PLoS One 6, e16957 (2011).

Mandal, R. et al. Multi-platform characterization of the human cerebrospinal fluid metabolome: a comprehensive and quantitative update. Genome Med 4, 38 (2012).

Raffler, J. et al. Genome-Wide Association Study with Targeted and Non-targeted NMR Metabolomics Identifies 15 Novel Loci of Urinary Human Metabolic Individuality. PLoS Genet 11, e1005487 (2015).

Klepacki, J. et al. Amino acids in a targeted versus a non-targeted metabolomics LC-MS/MS assay. Are the results consistent? Clin Biochem 49, 955–61 (2016).

Yet, I. et al. Genetic Influences on Metabolite Levels: A Comparison across Metabolomic Platforms. PLoS One 11, e0153672 (2016).

Mook-Kanamori, D. O. et al. 1,5-Anhydroglucitol in saliva is a noninvasive marker of short-term glycemic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99, E479–83 (2014).

Eckardt, K. U. et al. The German Chronic Kidney Disease (GCKD) study: design and methods. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27, 1454–60 (2012).

Prokosch, H. U. et al. Designing and implementing a biobanking IT framework for multiple research scenarios. Stud Health Technol Inform 180, 559–63 (2012).

Titze, S. et al. Disease burden and risk profile in referred patients with moderate chronic kidney disease: composition of the German Chronic Kidney Disease (GCKD) cohort. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30, 441–51 (2015).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1, 307–10 (1986).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the willingness of the patients to participate in the GCKD study. The enormous effort of the study personnel of the various regional centers is highly appreciated. We thank the large number of nephrologists who provide routine care for the patients and collaborate with the GCKD study. A list of nephrologists currently collaborating with the GCKD study is available at http://www.gckd.org. A list of the GCKD Investigators is included in Supplementary Information. The GCKD study is funded by grants from the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant number 01ER0804), the KfH Foundation for Preventive Medicine and corporate partners. The work of AK was funded by the CRC 1140 and grant KO 3598/3-1 of the German Research Foundation (DFG). KS was supported by ‘Biomedical Research Program’ funds at Weill Cornell Medicine in Qatar, a program funded by the Qatar Foundation. The article processing charge was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the University of Freiburg in the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: W.G., K.U.E., K.S., G.K., P.J.O., A.K. Data acquisition/data analysis: P.S., K.D., F.C.V., L.E., R.P.M., A.K. Drafting of manuscript: P.S., K.D., G.K., A.K. Revision/final approval of manuscript: P.S., K.D., F.C.V., W.G., L.E., R.P.M., K.U.E., K.S., G.K., P.J.O., A.K. The corresponding author (P.S.) has full access to the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

RPM is employed by Metabolon, Inc. He contributed to the logistics and optimization of MS spectrometry and to MS data interpretation. Metabolon Inc. was not involved in the design of the study, statistical analysis or interpretation of the results.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sekula, P., Dettmer, K., Vogl, F.C. et al. From Discovery to Translation: Characterization of C-Mannosyltryptophan and Pseudouridine as Markers of Kidney Function. Sci Rep 7, 17400 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17107-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17107-5

This article is cited by

-

Urinary metabolite profiling and risk of progression of diabetic nephropathy in 2670 individuals with type 1 diabetes

Diabetologia (2022)

-

Quantification of serum C-mannosyl tryptophan by novel assay to evaluate renal function and vascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Yeast- and antibody-based tools for studying tryptophan C-mannosylation

Nature Chemical Biology (2021)

-

The relationship between blood metabolites of the tryptophan pathway and kidney function: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Monomeric C-mannosyl tryptophan is a degradation product of autophagy in cultured cells

Glycoconjugate Journal (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.