Abstract

The magnetic transition-metal (TM) @ oxide nanoparticles have been of great interest due to their wide range of applications, from medical sensors in magnetic resonance imaging to photo-catalysis. Although several studies on small clusters of TM@oxide have been reported, the understanding of the physical electronic properties of TMn@(ZnO)42 is far from sufficient. In this work, the electronic, magnetic and optical properties of TMn@(ZnO)42 (TM = Fe, Co and Ni) hetero-nanostructure are investigated using the density functional theory (DFT). It has been found that the core-shell nanostructure Fe13@(ZnO)42, Co15@(ZnO)42 and Ni15@(ZnO)42 are the most stable structures. Moreover, it is also predicted that the variation of the magnetic moment and magnetism of Fe, Co and Ni in TMn@ZnO42 hetero-nanostructure mainly stems from effective hybridization between core TM-3d orbitals and shell O-2p orbitals, and a magnetic moment inversion for Fe15@(ZnO)42 is investigated. Finally, optical properties studied by calculations show a red shift phenomenon in the absorption spectrum compared with the case of (ZnO)48.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Semiconducting hybrid materials with improved functionalities such as optical, electric and magnetic properties have been considered as potential candidates for a wide range of applications. For example, Rh, Pd and Pt particles supported on oxides, such as CeO2 and Al2O3, are widely used in catalysis1,2; magnetic iron-oxide nanoparticles have been investigated as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging3, which is of important use in cancer therapy. In particular, the physical properties of ZnO doped with ions of transition metal elements have been one of the most intriguing research topics in current materials science4,5,6,7,8,9. The characteristics of ZnO with Zn being a transition metal enables it to easily dope magnetic transition metal (TM) ions such as Mn2+, Fe3+, Co2+ and Ni2+ in place of Zn2+ in the crystal of ZnO. Dietl et al. discovered room temperature ferromagnetism in Mn- doped ZnO thin film, receiving tremendous attention to ZnO based materials10. Since then several studies have been carried out in ZnO based materials with different combinations of TM ions4,11,12. Some reports revealed the importance of point defects such as oxygen, zinc vacancies and interstitials in magnetic ordering13,14. Mishra and Das15 studied the optical characteristics of Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles using FTIR. Sawalha et al.16 investigated the electrical conductivity of pure and doped ZnO ceramic systems. Their experiments indicated that donor concentration, point defects, and adsorption–desertion of oxygen were affected by the Fe doping for ZnO. Moreover, Shi and Duan17 studied the magnetic properties of TM (Cr, Fe and Ni) doped in ZnO nanowires by first-principles theory. Xiao et al.18 calculated the structural and electronic properties of Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles, and the results showed that Fe doped ZnO nanoparticles were structurally more stable than the isolated FeO and ZnO phases.

In recent years, core-shell structures in which metals form the core and ZnO constitutes the shell have attracted intense interest due to their significantly high effectiveness in improving the photo-catalytic activity and the synergistic effect among components19,20,21,22. The core-shell architecture avoids exposing the inner core to the environment and thus maximizes the interaction between the building blocks. Moreover, the composition, size and morphology of the inner core and outer shell are important aspects of structural property and would most probably affect its stability. So far, to the best of our knowledge, investigations on the physical mechanism for the effect of composition, size and morphology of magnetic TM-core/ZnO-shell heterogeneous nanoparticles are very rare. Here, we report the theoretical studies on a series of TMn@(ZnO)42 (TM = Fe, Co and Ni) heterostructures by using the density functional theory (DFT). The structural, magnetic and optical properties of such core-shell heterostructures have been investigated. Variation of magnetic moment are studied and stable structures are founded among different models, especially for the moment inversion of Fe15@(ZnO)42. Furthermore, a red shift phenomenon is also obtained for the absorption spectrum of Fe15@(ZnO)42 compared with the case of (ZnO)48. We expect that our results for TMn@(ZnO)42 can help to understand the effects of the encapsulation on the structure, stability, and magnetic properties of TM clusters.

Results and Discussion

The structural properties of TMn@(ZnO)42 hetero-nanostructure

In simulation, due to the multiplicity and indeterminacy of core-shell hetero-structure, it is always a challenge to optimize the stable structure of metal-oxide heterogeneous with increasing number of atoms. In the following calculations, the TMn@(ZnO)42 core-shell model is built to investigate stable structure of TMn@(ZnO)42 with different n (n = 6–18). Considering the rationality of the structure, the magic number nanostructure of (ZnO)48 with D 3d symmetry is firstly chosen to be the initial configurations due to the fact that the (ZnO)48 model has the highest binding energy23. Therefore, six ZnO in the center of relaxed (ZnO)48 are removed, and magnetic TM-core TMn clusters are constructed. The central empty position to put the magnetic TM-core relies on their lowest energy configurations according to the literatures24 with some considerations on the chemical bond length and interatomic interaction. Then, core-shell nanostructures of TMn@(ZnO)42 which contain TMn inner core atoms and ZnO outer shell with 42 pairs of Zn-O atoms are built. First, all atoms are fully relaxed by using conjugate gradient algorithm and reach the criteria of the convergence tolerance for energy and maximum force. To further test the thermodynamic stability, we perform first-principles molecular dynamic simulations with a Nose-Hoover thermostat at 500 K in the canonical NVT ensemble. During the whole process of 10 ps simulations, the trajectories are calculated with a chosen time step of 1 fs. We find that there is no structure transform of the Fen@(ZnO)42 core-shell phase, except for Fe7@(ZnO)42 (see the Supporting Information I). Then, we optimize the structure of the annealed Fe7@(ZnO)42 and replace the original structure. These results suggest that combination of the structure optimization and molecular dynamic simulations is needed for the precise prediction of structure.

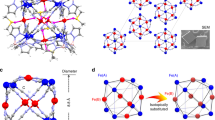

According to our scheme, the stable configurations of TMn@(ZnO)42 clusters are obtained as shown in Fig. 1. The inner core TMn and outer shell (ZnO)42 configurations separated from the optimized geometry configurations of TMn@(ZnO)42 are also illustrated in Fig. 1. It is noted that the encapsulated TMn (n = 6–7 for Fe, n = 6–9 for Co and Ni) clusters shift towards the (ZnO)42 inside surface, indicating the presence of an attractive interaction of the TMn clusters caused by the (ZnO)42 inside surface. However, large TMn clusters (n = 8–16 for Fe, n = 10–18 for Co and Ni) are nearly located at the center of the cages due to the inner core TMn cluster and outer shell cage sizes. The shells of n from 6 to 12 are a cage-like structure while the shells of n ≥ 13 have a tendency to change into a sphere, which may imply that with the increase of n, the shell is increasingly inclined to become a spherical structure. The exact symmetry for each TM cluster is C1 except that Ni12 is C2. The nine kinds of Fen (n = 6–13 and 15) inner core configurations picked from the optimized geometry configurations of Fen@(ZnO)42 are displayed in Fig. 2 for the convenience of comparison with the structure of Fen clusters demonstrated in the literature24. It can be seen that large parts of the core structure of Fen@(ZnO)42 are not similar to the case of Fen, which is mainly due to the TM-oxygen interaction. Furthermore, it is intriguing that, in the TMn clusters, the TM atom located at the prominent position and the center of TMn (yellow balls in Fig. 1) have relatively small local magnetic moments. Therefore, there is a strong tendency of the magnetic TMn clusters for lower symmetry structures, which helps to increase their energy stability due to the splitting of the highest occupied states. From the results of bond lengths (see Fig. 1), the Fen clusters are much more non-compact than the Con and Nin structures, indicating that the core is more close to shell for Fen@(ZnO)42. This trend may affect the magnetic moments (see Supporting Information II) of the TMn@(ZnO)42 systems and induce more abnormal effect. (e.g. the atom with larger local magnetic moments for Fe shows inversion for the Fe atoms close to O atoms).

The optimized geometries of TMn@(ZnO)42 core-shell nanostructure. The pink, purple and blue balls show the positions of O, Zn and TM atoms, respectively. The small or abnormal magnetic moment of TM atoms are shown by yellow balls. The numbers below the inner core configurations indicate the average bond lengths (Å) within 3.00 Å (see Supporting Information III and supporting information I for enlarged picture of core-shell structures).

To investigate the structural stability, second-order differences of total energies (Δ 2 E) for TMn@(ZnO)42 nanostructure are calculated and displayed in Fig. 3. The second-order differences of total energies are calculated by equation:

where E n and n refer to the total energy of TMn@(ZnO)42 and the number of TM atoms, respectively.

The second-order differences of total energies Δ 2 E n of TMn@(ZnO)42 nanostructure. It is noted that the largest Δ 2 E n are found at n = 13, 15 and 15 for TM = Fe, Co and Ni in TMn@(ZnO)42 core-shell structures, respectively, indicating that Fe13@(ZnO)42, Co15@(ZnO)42 and Ni15@(ZnO)42 are the most stable structure.

As shown in Fig. 3, the relatively large peaks of Δ 2 E n are found at n = 13, 15 and 15 for TM = Fe, Co and Ni in TMn@(ZnO)42 core-shell structures, respectively, demonstrating that Fe13@(ZnO)42, Co15@(ZnO)42 and Ni15@(ZnO)42 are the most stable configurations among all the clusters in the size range of the present study. It is also find that clusters of 7, 13 and 15 atoms are particularly stable, and these three sizes for metal cluster are well-known “magic numbers”25. The calculated Zn-O bond lengths and O-Zn-O bond angle of the (ZnO)48 and M@ZnO (we use M@ZnO to represent all TMn@(ZnO)42 for TM = Fe, Co, Ni and n = 13, 15, 15 in the following discussion) are listed in Table 1 together with other calculated work23, from which it can be seen that our results of (ZnO)48 reach an agreement with the other studies23. It is also obvious that there is a contraction behavior for the outer-shell of M@ZnO compared with (ZnO)48, indicating that doping at the center with a magnetic TM atom could provide strong bonding among surface atoms, that is, the Zn-O bonding of M@ZnO is stronger than the (ZnO)48 cluster due to the interaction of M-O.

The magnetic and electronic structure properties of TMn@(ZnO)42 hetero-nanostructure

The magnetic properties of encapsulated TMn (TM = Fe, Co and Ni) clusters inside (ZnO)42 are calculated based on the stable geometries discussed above. All of the transition metal atom magnetic moments of the TMn@(ZnO)42 core-shell nanostructure are shown in Tables 2–4. More details of magnetic moments are described in the Supporting Information II. The following trends can be observed: (i) Except for a few cases, the magnetic moments decrease from outside to inside for core transition metal atoms. For example, for relatively stable structure Fe15@(ZnO)42, Co15@(ZnO)42, and Ni13@(ZnO)42, the center Fe, Co, Ni atoms have the magnetic moments 1.996, 1.167, and 0.226 μB/atom, which are significantly smaller than the other magnetic moments such as 2.64, 1.78, and 0.68 μB/atom, the average value for Fe, Co and Ni, respectively. (ii) As is presented in Table 5, a general feature is that local magnetic moments tend to have some relationship with the TM-O distance and the small distance corresponds to a small magnetic moment. Especially for several Fen@(ZnO)42 systems, e.g., Fe15@(ZnO)42, it is found that some Fe local magnetic solutions change from ferromagnetic to antiferromagnetic phases (e.g. −2.176 μB/atom) with the Fe-O distance decreased. A similar phenomenon can also be found in the TM@Mg12O12 26 and TM m @C n 27. (iii) For most of the systems, we observed a large number of atomic configurations with slightly different magnetic moments. These results indicate that one of the magnetic configurations might be more favorable or a wide range of magnetic configurations might exist at real experimental conditions, and experimental techniques might access only the average results.

To obtain a better understanding for the origin of TM magnetic moments difference, we take relatively stable compound mentioned above as examples to present the charge density difference and investigate the p-O and d-TM projected DOS (see Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Charge transfer data of the typical atom have been marked out in Fig. 4, demonstrating that, apart from the transition metal atoms neighboring oxygen atoms, the charge transfer numbers increase from outside to inside for core transition metal atoms. For instance, the Fe, Co, Ni atoms at the center of core have the charge transfer numbers 0.1431, 0.2181 and 0.2155, which are much larger than the numbers of other transition metal atoms and correspond to smaller magnetic moments as discussed previously. More intriguingly, because of the interaction with O atoms, transition metal atoms near O atoms have a large charge transfer, leading to smaller magnetic moment and even magnetization reversal has been found.

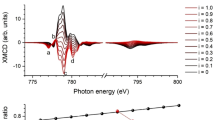

Figure 5 shows the PDOS of the representative atoms for up (↑) and down (↓) spins, demonstrating differences in the shape of PDOS among transition metal atoms at different position. This shape differences are mainly a shift to high energy or low energy, which can be explained by the decrease or increase of the effective hybridization between core TM-3d orbitals and the shell O-2p orbitals, resulting in the charge transfer from core TM to shell O. The charge density difference is demonstrated in Fig. 4. Near to the Fermi level (\({{\rm{E}}}_{{\rm{F}}}\)), a large overlap between O 2p and TM 3d is clearly seen for atoms with minimal TM-O distance, showing a strong hybridization between O and TM atoms. This also explains why all the core-shell clusters have relative large core-shell interaction energy.

In the case of Fe15@(ZnO)42, as the interaction of TM-O increases, spin-split becomes significant for the d- projected DOS, resulting in a large magnetic moment change from the center of the core to the edge of the core. In Fig. 4, we take Fe5, Fe9 and Fe14 as an example. Fe5 is in the center of the core with a magnetic moment 1.996 μB/atom. Fe9 and Fe14 are located on the edge of the core with a moment −2.714 μB/atom and −0.767 μB/atom, indicating an inverse direction compared with other moments. It can be seen that the O atoms neighboring Fe9 and Fe14 are O33 and O31 respectively. At the same time, these two O atoms have the largest two negative magnetic moments (−0.108 μB/atom and −0.064 μB/atom) and they have a very large charge transfer at the same time. So the moment inversion could be interpreted by the strong interaction between Fe-O atoms, which could also be utilized to understand the magnetic moment difference for different core atoms. Similar spin-split can also be seen in Co15@(ZnO)42 and Ni13@(ZnO)42, where the spin-up and spin-down DOS become asymmetric. For Co and Ni at more outer positions or with smaller TM-O distances, this asymmetry is more significant. For Co15@(ZnO)42 and Ni13@(ZnO)42, spin-split becomes less obvious because of the weaker TM-O interaction than Fe15@(ZnO)42, resulting in the less magnetic moment change. For instance, magnetic moment for Co15@(ZnO)42 is 1.167 μB/atom for Co8 at the center of core, 1.861 μB/atom (Co1) for atom at the edge of core but far from O atom. And 1.700 μB/atom (Co7) for atom at the edge is close to O (O17) atom. At the same time, see Figs 4 and 5, the moment of O (O17) close to Co (Co7) is 0.059 μB/atom and the moment of O (O29) near Ni (Ni6) is 0.027 μB/atom, which is not large enough and leads to less TM moment changes. Moreover, in Fig. 4, less charge transfer from core Co or Ni to shell O also shows weaker interaction than Fe15@(ZnO)42.

In addition, it is indicated from Table 5 and Supporting Information II that the magnetic moment of transition metal is related to the coordination number, the average TM-TM bond length and the distance of TM-O, e.g. large coordination number usually lead to small magnetic moment; and a small bond length of TM-TM or TM-O also tends to result in a small moment. The variation moments of TM atom may arise from the contribution of the synergistic effect of the coordination number and bond length. For Co, Ni atoms at the center of the core, their moments are small due to the largest coordination number among all the core atoms. Although Co1 has a larger coordination number compared with Co11, the average bond length between Co1 and neighbor Co atoms (2.458 Å) is larger than the case of Co11 with adjacent Co atoms (2.448 Å). At the same time, the distance of Co-O atoms is largest for Co1-O. As a result, the final moment of Co1 is strongest in Co15@(ZnO)42, indicating that the magnetic moment of atoms are deeply related to the geometry configuration of each atoms, which is consistent with the result from charge transfer.

Indeed, although the 3d orbitals are usually spatially extended and the delocalization is even more enhanced by hybridization with oxygen orbitals in TMn@(ZnO)42, electron correlations can still play an important role in 3d systems, especially for Fen@(ZnO)42 where the electronic configuration maximizes the correlation effects due to the delicate balance of charge states in Fen@(ZnO)42. Thus, we then focus on the results obtained at Coulomb energy U = 4.5 eV and exchange parameter J = 0.89 eV for all Fe ions.

As given in Tables 2 and 3, a general feature is that inclusion of U leads to local magnetic moments increased. Comparing the results for the magnetic state with and without U, for example, for relatively stable structure Fe15@(ZnO)42, we find that U will lead to different correlation behaviors with various Fe-O distances: (I)The center Fe atom shows the magnetic moments 2.718 μB/atom, which are smaller than the other values (3.056 μB/atom), which is consistent with the LDA results. (II) For the medium Fe-O distance, Fe correspond to an intermediately correlated by U and magnetic moment tend to around 3 μB/atom, which consistent with the literature value28. (III) Our LDA + U calculations finding a significant role of electron-electron correlations in small Fe-O distance atoms. Especially for the two nearest distances, it is found that the Fe local magnetic solutions change from antiferromagnetic (−2.176, −0.767) to ferromagnetic (3.093, 3.093) phases. From this point of view, stronger interaction of Fe-O makes the magnetic value and ordering more sensitive to correlation effects. And a similar phenomenon can also be found in the other Fen@(ZnO)42 compounds.

This can also be observed by comparing the DOS between the results from LDA and LDA+U, given in the Fig. 5(a). In Fe15@(ZnO)42, as the interaction of TM-O increases, spin-split become more obvious, resulting in a large magnetic moment change as compared with LDA result. For Fe9, with the strong interaction between Fe-O atom, the DOS spin-up shifted to lower energy and spin-down pushed towards higher energy more significantly. And inclusion of U leads to a transition of the magnetic ordering, coinciding with the above analyses. At the same time, charge density difference also reflects the same tendency (see Fig. 4(a)).

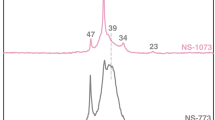

The optical properties of M@ZnO and (ZnO)48

In order to investigate the influence of magnetic TM inner-core on the optical properties of ZnO shell cage, the dielectric function of M@ZnO and pure (ZnO)48 nanostructures are all calculated for comparison and the optical absorption of core-shell structure and pure (ZnO)48 is illustrated in Fig. 6. Compared with the (ZnO)48, the optical absorption peaks of core-shell structure Fe13@(ZnO)42, Co15@(ZnO)42 and Ni15@(ZnO)42 have an obvious red shift at 147.56 nm, compared with pure (ZnO)48 at 123.95 nm, which is due to the effect of Fe, Co, Ni core. The spectral line of the Ni15@(ZnO)42 appeared to have a smaller peak at about 255.84 nm while both Fe13@(ZnO)42 and Co15@(ZnO)42 have no peak there. According to the DOS of Ni15@(ZnO)42 (shown in Fig. 5(d)), we found that this smaller peak originates from the stronger interaction between Ni-O atoms and more abundant charge transfer of O–Zn atom (see Supporting Information II). We contrast the DOS of M@ZnO (Fig. 5(d)) and conclude that the influence on Zn-O interaction for the case of introducing Ni atoms is weaker than the case of Co, Fe atoms, particularly at <3 eV. Moreover, it is noted that, at around the 400 nm (in the visible light), all the core-shell structures and (ZnO)48 have a distinct peak, although with some differences in the height of the peak, coming from the contribution of electrons transfer of O–Zn atom at shell.

Figure 6 also exhibits the imaginary part and real part of dielectric function of M@ZnO and pure (ZnO)48. For the real part of dielectric function of Fe13@(ZnO)42, Co15@(ZnO)42 and Ni15@(ZnO)42, It is found that there are no obvious differences among them. Moreover, both of the real parts of dielectric functions of (ZnO)48 and M@ZnO are all positive. Unlike the M@ZnO, in the lower energy region (<3.2 eV), (ZnO)48 does not have a major peak and is quite smooth but in the higher energy region (>10 eV), all of the tendency of curves become consistent with each other. In addition, as the DOS presented in Fig. 5(d), M@ZnO shows a typical half-metallic behavior from spin majority and minority components, which is in keeping with the result of the real part of dielectric function. In addition, the spin polarization of Fe, Co and Ni is the major contribution for DOS around the Femi level.

Furthermore, the imaginary part of dielectric function shows that the curve of (ZnO)48 has no distinct peak while M@ZnO appears to have a larger peak at around 0.85–1.47 eV, which is mainly due to the contribution of Co, Fe, Ni atoms in the core. It indicates that there is an evident absorptive action in the infrared region and the margin of visible light, especially in the case of Fe15@(ZnO)42, whose peak of absorption is closer to the visible light region. Finally, due to the interaction between O atom in shell and metal atom in core, the peak at 9.68 eV of (ZnO)48 vanishes and the curve decreases to zero rapidly.

Conclusions

The structural, magnetic and optical properties of TMn@(ZnO)42 (TM = Fe, Co and Ni) core-shell nanostructures are studied by the First-principles calculations. Our results indicate that Fe13@(ZnO)42, Co15@(ZnO)42 and Ni15@(ZnO)42 core-shell nanostructure are the most stable configurations. Compared with (ZnO)48 value, the Zn-O bonding of M@ZnO is stronger due to the interaction of TM-O. The special magnetism mainly effect by O atoms and TM atoms, which can be attributed to the strong TM-O hybridization and charge transfer. It is also found that this strong interaction induces some magnetic moment inversion for Fe13@(ZnO)42. Furthermore, the optical properties of M@ZnO are systematically investigated based on absorption coefficient. Compared with the absorption spectrum of the (ZnO)48, we find that an obvious red shift has occurred, and it is in accordance with the behavior of the calculated electronic structure.

Methods

All calculations in this paper are performed in the VASP codes29,30 based on density functional theory (DFT)31,32 within the projector augmented wave (PAW)33. The exchange and correlation potential is treated with the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) methods as described by Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE)34. The electron wave functions are expanded in plane wave with a cutoff energy of 480 eV. All atoms are fully relaxed and the convergence tolerance for energy and maximum force are set to 1.0 × 10−5 eV and −5 × 10−3 eV/Å. For k-point sampling, we use a single Γ point for the geometry optimizations in the first Brillouin zone. Spin-polarization is taken into account in this work. In a second step we supplement the LDA calculations by including a Coulomb energy U = 4.5 eV35 and exchange parameter J = 0.89 eV36 on Fe 3d orbitals within the LDA + U scheme. In the calculations, the free TMn@(ZnO)42 is located in a rectangular supercell with a size of 30 × 30 × 30 Å3. The interaction between periodic images could be neglected on this size.

In order to predict the stable structures, we perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations. The initial configuration of the Fen@(ZnO)42 is annealed at 500 K. MD simulations are carried out in the NVT ensemble with a time step of 1 fs for a total time of 10 ps. The temperature is controlled by using the Nosé–Hoover method37.

References

Silva, J. L. D. et al. Formation of the cerium orthovanadate Ce V O 4: DFT + U study. Physical Review B 76, 125117 (2007).

Vajda, S. et al. Subnanometre platinum clusters as highly active and selective catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Nat. Mater. 8, 213–216 (2009).

Braun, K. et al. Gain of a 500-fold sensitivity on an intravital MR contrast agent based on an endohedral gadolinium-cluster-fullerene-conjugate: a new chance in cancer diagnostics. Int J Med Sci 7, 136–146 (2010).

Sharma, P. et al. Ferromagnetism above room temperature in bulk and transparent thin films of Mn-doped ZnO. Nat. Mater. 2, 673–677 (2003).

Beltrán, J. et al. Magnetic properties of Fe doped, Co doped, and Fe + Co co-doped ZnO. Journal of Applied Physics 113, 17C308 (2013).

Tang, J. et al. Spin transport in Ge nanowires for diluted magnetic semiconductor-based nonvolatile transpinor. ECS Trans 64, 613–623 (2014).

Shanmuganathan, G. & Banu, I. S. Room temperature optical and magnetic properties of (Cu, K) doped ZnO based diluted magnetic semiconductor thin films grown by chemical bath deposition method. Superlattices Microstruct 75, 879–889 (2014).

Fusil, S. et al. Magnetoelectric devices for spintronics. Annual Review of Materials Research 44, 91–116 (2014).

Zhang, F. et al. Electronic Structure and Magnetism of Mn-Doped ZnO Nanowires. Nanomaterials 5, 885–894 (2015).

Dietl, T. et al. Zener model description of ferromagnetism in zinc-blende magnetic semiconductors. Science 287, 1019–1022 (2000).

Han, S. et al. Magnetism in Mn-doped ZnO bulk samples prepared by solid state reaction. Applied Physics Letters 83, 920–922 (2003).

Radovanovic, P. V. & Gamelin, D. R. High-Temperature Ferromagnetism in Ni2+ -Doped ZnO Aggregates Prepared from Colloidal Diluted Magnetic Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Physical review letters 91, 157202 (2003).

Hong, N. H. et al. Role of defects in tuning ferromagnetism in diluted magnetic oxide thin films. Physical Review B 72, 045336 (2005).

Elfimov, I. et al. Possible path to a new class of ferromagnetic and half-metallic ferromagnetic materials. Physical review letters 89, 216403 (2002).

Mishra, A. & Das, D. Investigation on Fe-doped ZnO nanostructures prepared by a chemical route. Materials Science and Engineering: B 171, 5–10 (2010).

Sawalha, A. et al. Electrical conductivity study in pure and doped ZnO ceramic system. Physica B 404, 1316–1320 (2009).

Shi, H. & Duan, Y. First-principles study of magnetic properties of 3 d transition metals doped in ZnO nanowires. Nanoscale Res Lett 4, 480 (2009).

Xiao, J. et al. Evidence for Fe2 + in wurtzite coordination: iron doping stabilizes ZnO nanoparticles. Small 7, 2879–2886 (2011).

Dhiman, P. et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel Fe@ZnO nanosystem. Journal of alloys and compounds 578, 235–241 (2013).

Biswas, S. et al. Semiconducting properties of a ferromagnetic nanocomposite: Fe@ ZnO. Indian J Phys 89, 703–708 (2015).

Majhi, S. M. et al. Facile approach to synthesize Au@ZnO core–shell nanoparticles and their application for highly sensitive and selective gas sensors. ACS Appl Mat Interfaces 7, 9462–9468 (2015).

Das, S. et al. Solar-photocatalytic disinfection of Vibrio cholerae by using Ag@ZnO core–shell structure nanocomposites. J Photochem Photobiol, B 142, 68–76 (2015).

Li, C. et al. First-principles study on ZnO nanoclusters with hexagonal prism structures. Applied physics letters 90, 223102 (2007).

Qing-Min Ma et al. Structures, binding energies and magnetic moments of small iron clusters: A study based on all-electron DFT. Solid State Communications 142, 114–119 (2007).

Sakurai, M. et al. Magic numbers in transition metal (Fe, Ti, Zr, Nb, and Ta) clusters observed by time-of-flight mass spectrometry. The Journal of Chemical Physics 111, 235 (1999).

Javan, M. B. Magnetic properties of Mg 12 O 12 nanocage doped with transition metal atoms (Mn, Fe, Co and Ni): DFT study. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 385, 138–144 (2015).

Tereshchuk, P. & Silva, J. L. D. Encapsulation of small magnetic clusters in fullerene cages: A density functional theory investigation within van der Waals corrections. Physical Review B 85, 195461 (2012).

Horng-Tay Jeng et al. Charge-Orbital Ordering and Verwey Transition in Magnetite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 156403 (2004).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Physical Review B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Computational Materials Science 6, 15–50 (1996).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Physical review 136, B864 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Physical review 140, A1133 (1965).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Physical Review B 59, 1758 (1999).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Physical review letters 77, 3865 (1996).

Anisimov, V. I. et al. Charge-ordered insulating state of Fe3O4 from first-principles electronic structure calculations. Phys. Rev. B 54, 4387 (1996).

Anisimov, V. I., Zaanen, J. & Andersen, O. K. Band theory and Mott insulators: Hubbard U instead of Stoner I. Phys. Rev. B 44, 943 (1991).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank Xingyun Zhu and Qihang Zhang for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. Hu, C.T. Ji and Q. Liu performed the DFT calculation. Y.W. Hu, X.X. Wang and J.R. Huo wrote the manuscript. Y.P. Song gave instruction on this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Ji, C., Wang, X. et al. The structural, magnetic and optical properties of TMn@(ZnO)42 (TM = Fe, Co and Ni) hetero-nanostructure. Sci Rep 7, 16485 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16532-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16532-w

This article is cited by

-

First-principles calculation of Aun@(ZnS)42 (n = 6–16) hetero-nanostructure system

Rare Metals (2020)

-

The selectivity of the transition metals encapsulated in a Fe9O12 cage

Research on Chemical Intermediates (2019)

-

Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic degradation of chlorpyrifos by novel Fe: ZnO nanocomposite material

Nanotechnology for Environmental Engineering (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.