Abstract

200 million patients suffer from malaria, a parasitic disease caused by protozoans of the genus Plasmodium. Reliable diagnosis is crucial since it allows the early detection of the disease. The development of rapid, sensitive and low-cost diagnosis tools is an important research area. Different studies focused on the detection of hemozoin, a major by-product of hemoglobin detoxification by the parasite. Hemozoin and its synthetic analog, β-hematin, form paramagnetic crystals. A new detection method of malaria takes advantage of the paramagnetism of hemozoin through the effect that such magnetic crystals have on Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) relaxation of water protons. Indeed, magnetic microparticles cause a shortening of the relaxation times. In this work, the magnetic properties of two types of β-hematin are assessed at different temperatures and magnetic fields. The pure paramagnetism of β-hematin is confirmed. The NMR relaxation of β–hematin suspensions is also studied at different magnetic fields and for different echo-times. Our results help to identify the best conditions for β–hematin detection by NMR: T 2 must be selected, at large magnetic fields and for long echo-times. However, the effect of β-hematin on relaxation does not seem large enough to achieve accurate detection of malaria without any preliminary sample preparation, as microcentrifugation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2015, 200 million patients were suffering from the tropical disease malaria, and half a million died from the infection the same year1. The protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium causing the disease are transferred to humans by Anopheles mosquito bites. In the fight against malaria, reliable diagnosis tools are crucial since they allow the early detection of the disease, which increases the efficiency of the treatments, but also because they prevent overprescription of antimalarial drugs which may lead to drug resistance. The standard diagnosis method consists in the examination of Giemsa stained blood smears by light microscopy, which requires efficient microscopes and trained microscopists. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) analysis of DNA extracted from the patient’s blood is also very sensitive, but rather expensive and difficult to use on the field. As the disease is mainly present in developing countries, the diagnosis tests must be rapid, cheap and easy to implement. Therefore, rapid diagnosis tests (RDTs) – based on lateral flow immunochromatographic detection of malaria antigens – were created and are now widely used2,3 even if their sensitivity is clearly lower than that of microscopy and PCR4,5. In this context, the development of new, rapid and sensitive diagnosis tools remains an important research area. Some groups focused on the detection of a major by-product of malaria infection, hemozoin. Indeed, during their proliferation in red cells, the parasites feed on haemoglobin, which results in the release of free heme. This redox agent being toxic, the parasite transforms it into an insoluble polymer, hemozoin, the so-called “malaria pigment”. Hemozoin and its synthetic analog, β-hematin, have comparable structural properties but their immunogenic properties may differ because of different crystal sizes and/or shapes6,7,8,9. They are both paramagnetic because they contain Fe3+ ions in high-spin configuration10,11,12,13. Values of the magnetic susceptibility of hemozoin and β-hematin were published by Brémard et al.10, Bohle et al.11, Hackett et al.14 and Butykai et al.15. In 2016, a study16 surprisingly proposed a superparamagnetic model for β-hematin, which however remains to be confirmed. The magnetic properties of hemozoin are at the origin of two detection methods which were recently proposed. The first method15,17 uses the magnetic moment of the pigment crystals to align them in a specific direction which makes them magnetically driven optical polarizers. The second method, evaluated by two different groups18,19, tries to take advantage of the paramagnetism of hemozoin through the effect that such magnetic crystals can have on Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) properties of neighbouring water protons in whole blood. Indeed, magnetic nano- and micro-particles cause a shortening of the relaxation times T 1 and T 2 of water protons, a phenomenon which is at the origin of the use of iron oxide particles as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) contrast agents. Karl et al.19 were the first to show the influence of hemozoin on water transverse relaxation time T 2. Even if the effect was noticeable, they concluded that it was unlikely that this technique could achieve the requested sensitivity to become an efficient diagnosis tool on the field, since they were only able to detect parasitemia levels higher than 10,000 parasites per µl of blood, corresponding to 0.2% infected Red Blood Cells (RBC). A few years later, Peng et al.18 and Kong et al.20 reported a new technique for the rapid and sensitive detection of Plasmodium infected RBC using the measurement of T 2. Their micromagnetic resonance relaxometry system uses the transverse relaxation of RBC pellets – obtained after microcentrifugation of a patient’s blood sample – to detect parasitemia levels of less than 10 parasites per µl, which is comparable to the detection limit of light microscopy, the gold standard. The marked discording conclusions of the two studies led to a reaction of Karl et al.21 who questioned the sensitivity reported by Peng et al.

In this work, the magnetic properties of two types of β-hematin will be assessed, to discriminate between paramagnetic and superparamagnetic behaviours, and the NMR relaxation of β-hematin-containing suspensions will be studied at different magnetic fields, in order to determine the best experimental conditions for the hemozoin and malaria detection by NMR.

Results

Electron Microscopy

Figure 1 shows the electron microscopy images of commercial and home-made synthetic β-hematin (“Mons sample”). As expected22, the crystals present a rod shape. An estimation of the mean size and standard deviation of the crystals long axis was obtained by measuring 60 particles. For the commercial sample, L = 1.01 ± 0.34 µm while for the Mons sample L = 0.67 ± 0.28 µm. This is slightly over the size of Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale and P. malariae hemozoin crystals (long axis, 0.30 to 0.50 µm)23.

Magnetometry

Figure 2 shows the dependence of the β-hematin samples magnetisation (expressed in Bohr magneton per iron ion) on magnetic field strength at 1.85 K. The curves do not present any hysteresis and are similar for both samples. The shape of the curves does not correspond to a Brillouin function, because of the anisotropy of the iron magnetic moments in the β-hematin crystals15. Our data are in agreement with previously published data obtained at 2 K15. A good agreement is also obtained when looking at the evolution of the magnetisation at 0.5 T with the inverse of temperature (1/T) (Fig. 3). Finally, the room temperature susceptibility of our samples is clearly comparable to what was previously reported for β-hematin and hemozoin (Table 1). However, our results are clearly not in agreement with the data of Inyushin et al.16 who observed a Langevin dependence of the magnetization with the field at room temperature, with a saturation magnetisation of about 60,000 A/m while we obtain a non-saturated magnetization of 450 A/m in similar conditions at 1.5 T, more than two orders of magnitude less.

NMR relaxometry

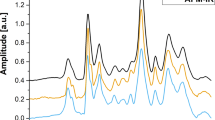

Figure 4 presents the T 1 NMRD profiles – the curve showing the evolution of the longitudinal relaxation rate with the magnetic field – of β-hematin suspensions. 1/T 1 monotonously decreases with the field for both samples with a broad dispersion after 1 MHz, similar to what was observed for methemoglobin24. The effect of β-hematin on the longitudinal relaxation of water is really weak. Indeed, the relaxation rate (1/T 1) normalised by the β-hematin concentration (in mg/mL) is always smaller than 0.55 s−1 mL mg−1. When expressed in terms of relaxivity – relaxation rate normalized by the iron concentration in mM – it gives less than 0.35 s−1 mM−1 which is far below the relaxivities of usual MRI contrast agents. This is also an order of magnitude smaller than the relaxivity of methemoglobin25. The transverse relaxation of water protons is more affected by the presence of β-hematin crystals as shown in Fig. 5. For both samples, the transverse relaxation rate 1/T 2 significantly increases with the field. This increase is more important for the commercial β-hematin compared to the Mons β-hematin. Such an increase reflects the field-dependent increase of the magnetic moment of the crystals. Their effect on transverse relaxation becomes stronger when they present larger magnetic moments. This is consistent with the predictions of the classical relaxation theories26. The transverse relaxation rate normalised by the β-hematin concentration (in mg/mL) are given in Table 2 for our samples at 20 MHz and 60 MHz together with values obtained from the literature. Finally, the influence of the interecho time on the transverse relaxation was also investigated. Transverse relaxation is more efficient for large interecho times as it is often the case for magnetic compounds (Fig. 6). The effect is more pronounced for the Mons sample. The differences of NMR results between the two samples can easily be explained by the differences of size and shape of the β-hematin crystals in the samples. It should here be stressed that the effect of paramagnetic crystals on the NMR relaxation of water protons is dependent on many parameters, not only on the magnetic susceptibility of the particles.

Discussion

Our results confirm the pure paramagnetism of β-hematin. It seems the superparamagnetism reported recently16 had another origin than the presence of β-hematin; this may come from a contamination of β-hematin by a superparamagnetic agent, such as hematite27. This clearly impacts the potential of conventional NMR relaxometry for the detection of malaria: paramagnetic particles are much harder to detect than superparamagnetic ones.

From the NMR point of view, graph 4 shows that transverse relaxation has to be used, since longitudinal relaxation is far too small. At 60 MHz, the normalized transverse relaxation rate obtained in this work (Table 2) is in good agreement with the value reported by Karl et al.19 for β-hematin suspensions. But our data bring more information: 1/T 2 increases with the field (Fig. 5) and also with the interecho time used in the CPMG sequence (Fig. 6). Using a large magnetic field is better, but it is hardly feasible in small and low-cost NMR systems. For example, the micromagnetic resonance system proposed by Peng used a field of 20 MHz. Moreover, long echo times are preferable to yield large values of 1/T 2, but they cannot be used in those micro-NMR systems whose magnetic field homogeneity is rather bad. For such systems, the purely instrumental dependence of T 2 on the echo time would mask the effect of β-hematin. This is why Peng et al. used an interecho time of 60 µs, a value smaller than the lowest value we tested.

A clear limitation of our study is the use of simple aqueous suspensions of β-hematin crystals instead of whole blood samples. The transposition of our conclusions to blood may not be straightforward. But to understand what is happening in blood, we believe that a first and necessary step is the study of simpler system, i.e. aqueous suspensions. In order to compare our results with those obtained for infected RBC samples containing hemozoin (from Karl et al. and Peng et al.), the following approximation was applied. Assuming that, in each parasitized RBC, 50% of hemoglobin has been converted into hemozoin, one can roughly estimate that an hemozoin content of 30 µg hemozoin/ml corresponds to a 1% parasitemia, as shown in Newman et al.17. This allows to normalize the 1/T 2 values obtained for infected RBCs samples (Table 2). The results of Karl et al. for hemozoin are in good agreement with our results for β-hematin. Considering only those results, it seems that conventional NMR relaxometry alone cannot be used for a sensitive diagnosis of malaria through detection of Plasmodium species: the normalized transverse relaxation rates of hematin/hemozoin are too small. This fully agrees with the conclusions of Karl et al.19 but not with those of Peng et al.18 who achieved an excellent sensitivity. Indeed, from Fig. 2a of the latter study, one can estimate that, for a parasitemia level of 1%, the transverse relaxation rate increase measured after centrifugation was 7 s−1. This leads to a normalized transverse relaxation rate which is about 170 times larger than what was obtained in this work for the same magnetic field. This difference in the normalized relaxation rate clearly explains the diverging conclusions of Karl et al. and Peng et al. The large value of the normalized relaxation rates obtained by Peng et al. may be related to the microcentrifugation step they applied before the NMR measurements. Indeed, centrifugation concentrates the infected red blood cells that present a higher density than the normal red blood cells. Moreover, in real blood, maybe the use of ultra-short echoes allows to probe other compartments of protons - like macromolecular protons28 - which could be more affected by the presence of hemozoin? Anyway, without preliminary centrifugation of the sample and the use of ultra-short echoes, the sensitivity of the NMR method would have been much worse. This is clearly something to take into account when trying to develop/adapt NMR methods for the detection of malaria: conventional relaxometry alone is not enough.

Methods

Samples

A sample of 5 mg of β-hematin (lot HMZ-38-01) was purchased from InvivoGen (Toulouse, France). This sample is referred to as “commercial β-hematin” throughout the paper.

A second sample of β-hematin was synthesized according to published protocols29,30 with slight modifications; briefly, a solution of 4.54 mM porcine hemin (Sigma-Aldrich, >98% pure) in 0.04 M NaOH was adjusted to pH 4.0 with 2% propionic acid dropwise and incubated at 70°C for 18 h. The formed crystals were filtered on cellulose, washed with 1 M acetic acid, dried over phosphorus pentoxide, manually powdered and stored at 4°C. The powder was characterized by infrared spectroscopy, yielding 3 bands characteristic of hemozoin7 at 1711, 1662 and 1209 cm−1. This sample is referred to as “Mons β-hematin” throughout the paper.

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy images were acquired directly on the powders with a Hitachi Scanning Electron Microscope, model SU8020 using a 3 kV voltage.

Magnetometry

All the magnetic measurements were carried out on a mini high field measurement system from Cryogenics Limited (London, UK) with the vibrating sample option. The maximum field is 5 T and the minimum temperature is 1.7 K. The measurements were directly performed on powders of β-hematin. When the diamagnetic contribution of the sample holder was non negligible (more than 1% of the total magnetic moment), it was subtracted from the raw data. It was especially the case at low fields and high temperature. For the comparison of the susceptibility values with the literature data, the density of β-hematin was needed. We used the value of 1440 kg/m3 reported by Coronado et al.8. The molecular weight of β-hematin was taken as 633.5 g/mol.

NMR relaxometry

For NMR results, the magnetic field is expressed in terms of the proton Larmor frequency: a field of 1 Tesla corresponds to a Larmor frequency of 42.6 MHz. The suspensions were sonicated during 3 min before the session of NMR measurements and the tubes were vigorously shaken by hand before each NMR measurement. Low-field NMRD profiles (T 1) of aqueous suspensions were measured from 0.015 to 40 MHz with a Spinmaster fast field-cycling relaxometer (STELAR, Mede, Italy) using 600 µL of suspensions in a dedicated NMR tube. The T 2 and T 1 measurements at higher fields were carried out on a homemade variable field relaxometry system using an electromagnet and a lapNMR RF spectrometer covering a range of Larmor frequency from 10 to 90 MHz. The CPMG sequence was used, with an interecho time of 1 ms unless other mention. The temperature of all the NMR measurements was 25 °C ± 1°C.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

WHO|World Malaria Report 2015. WHO Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2015/report/en/. (Accessed: 13th April 2017).

Abba, K. et al. Rapid diagnostic tests for diagnosing uncomplicated non-falciparum or Plasmodium vivax malaria in endemic countries. in Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011431.

Batwala, V., Magnussen, P., Hansen, K. S. & Nuwaha, F. Cost-effectiveness of malaria microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests versus presumptive diagnosis: implications for malaria control in Uganda. Malar. J. 10, 372 (2011).

Reyburn, H. et al. Rapid diagnostic tests compared with malaria microscopy for guiding outpatient treatment of febrile illness in Tanzania: randomised trial. BMJ 334, 403–403 (2007).

Gatti, S. et al. A comparison of three diagnostic techniques for malaria: a rapid diagnostic test (NOW Malaria), PCR and microscopy. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 101, 195–204 (2007).

Slater, A. F. et al. An iron-carboxylate bond links the heme units of malaria pigment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 325–329 (1991).

Jaramillo, M. et al. Synthetic Plasmodium-like hemozoin activates the immune response: a morphology - function study. PloS One 4, e6957 (2009).

Coronado, L. M., Nadovich, C. T. & Spadafora, C. Malarial hemozoin: From target to tool. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 1840, 2032–2041 (2014).

Coban, C. et al. The malarial metabolite hemozoin and its potential use as a vaccine adjuvant. Allergol. Int. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Allergol. 59, 115–124 (2010).

Brémard, C., J. Girerd, J., C. Merlin, J. & Moreau, S. Iron (III) porphyrin aggregates grafted on agarose gel as models of hemoglobin degradation products. J. Mol. Struct. - J MOL STRUCT 267, 117–122 (1992).

Bohle, D. S. et al. Structural and Spectroscopic Studies of β-Hematin (the Heme Coordination Polymer in Malaria Pigment). In Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers II 572, 497–515 (American Chemical Society, 1994).

Bohle, D. S., Debrunner, P., Jordan, P. A., Madsen, S. K. & Schulz, C. E. Aggregated Heme Detoxification Byproducts in Malarial Trophozoites: β-Hematin and Malaria Pigment Have a Single S = 5/2 Iron Environment in the Bulk Phase as Determined by EPR and Magnetic Mössbauer Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 8255–8256 (1998).

Sienkiewicz, A. et al. Multi-frequency high-field EPR study of iron centers in malarial pigments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4534–4535 (2006).

Hackett, S., Hamzah, J., Davis, T. M. E. & St Pierre, T. G. Magnetic susceptibility of iron in malaria-infected red blood cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1792, 93–99 (2009).

Butykai, A. et al. Malaria pigment crystals as magnetic micro-rotors: key for high-sensitivity diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 3, 1431 (2013).

Inyushin, M. et al. Superparamagnetic Properties of Hemozoin. Sci. Rep. 6, 26212 (2016).

Newman, D. M. et al. A Magneto-Optic Route toward the In Vivo Diagnosis of Malaria: Preliminary Results and Preclinical Trial Data. Biophys. J. 95, 994–1000 (2008).

Peng, W. K. et al. Micromagnetic resonance relaxometry for rapid label-free malaria diagnosis. Nat. Med. 20, 1069–1073 (2014).

Karl, S., Gutiérrez, L., House, M. J., Davis, T. M. E. & St Pierre, T. G. Nuclear magnetic resonance: a tool for malaria diagnosis? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 85, 815–817 (2011).

Fook Kong, T. et al. Enhancing malaria diagnosis through microfluidic cell enrichment and magnetic resonance relaxometry detection. Sci. Rep. 5 (2015).

Karl, S., Mueller, I. & St Pierre, T. G. Considerations regarding the micromagnetic resonance relaxometry technique for rapid label-free malaria diagnosis. Nat. Med. 21, 1387–1387 (2015).

Solomonov, I. et al. Crystal nucleation, growth, and morphology of the synthetic malaria pigment beta-hematin and the effect thereon by quinoline additives: the malaria pigment as a target of various antimalarial drugs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2615–2627 (2007).

Noland, G. S., Briones, N. & Sullivan, D. J. The shape and size of hemozoin crystals distinguishes diverse Plasmodium species. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 130, 91–99 (2003).

Koenig, S. H., Brown, R. D. & Lindstrom, T. R. Interactions of solvent with the heme region of methemoglobin and fluoro-methemoglobin. Biophys. J. 34, 397–408 (1981).

Bertini, I., Luchinat, C. & Parigi, G. 1h nmrd profiles of paramagnetic complexes and metalloproteins. in (ed. Chemistry, B.-A. in I.) 57, 105–172 (Academic Press, 2005).

Gillis, P., Moiny, F. & Brooks, R. A. OnT2-shortening by strongly magnetized spheres: A partial refocusing model. Magn. Reson. Med. 47, 257–263 (2002).

Strangway, D. W., McMahon, B. E., Honea, R. M. & Larson, E. E. Superparamagnetism in hematite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2, 367–371 (1967).

Stanisz, G. J., Li, J. G., Wright, G. A. & Henkelman, R. M. Water dynamics in human blood via combined measurements of T2 relaxation and diffusion in the presence of gadolinium. Magn. Reson. Med. 39, 223–233 (1998).

Blauer, G. & Akkawi, M. On the preparation of beta-haematin. Biochem. J. 346, 249–250 (2000).

Ncokazi, K. K. & Egan, T. J. A colorimetric high-throughput β-hematin inhibition screening assay for use in the search for antimalarial compounds. Anal. Biochem. 338, 306–319 (2005).

Acknowledgements

F.R.S.-FNRS and UMONS are acknowledged for financial support. Sophie Laurent and Céline Hénoumont are acknowledged for the access to the field cycling relaxometer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.O.N. and P.D. synthesized the β-hematin sample, Y.G. and Q.L.V. performed the experiments, Y.G. wrote the main manuscript and all authors reviewed the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gossuin, Y., Okusa Ndjolo, P., Vuong, Q.L. et al. NMR relaxation properties of the synthetic malaria pigment β-hematin. Sci Rep 7, 14557 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15238-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15238-3

This article is cited by

-

Hemozoin in malaria eradication—from material science, technology to field test

NPG Asia Materials (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.