Abstract

Non-forest ecosystems (predominant in semi-arid and arid regions) contribute significantly to the increasing trend and interannual variation of land carbon uptake over the last three decades, yet the mechanisms are poorly understood. By analysing the flux measurements from 23 ecosystems in Australia, we found the the correlation between gross primary production (GPP) and ecosystem respiration (Re) was significant for non-forest ecosystems, but was not for forests. In non-forest ecosystems, both GPP and Re increased with rainfall, and, consequently net ecosystem production (NEP) increased with rainfall. In forest ecosystems, GPP and Re were insensitive to rainfall. Furthermore sensitivity of GPP to rainfall was dominated by the rainfall-driven variation of LAI rather GPP per unit LAI in non-forest ecosystems, which was not correctly reproduced by current land models, indicating that the mechanisms underlying the response of LAI to rainfall should be targeted for future model development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

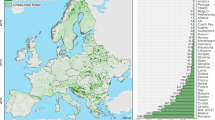

Recent studies have demonstrated that both the trend and inter-annual variation (IAV) of terrestrial carbon uptake over the past three decades were dominated by global non-forest (not covered with forest) ecosystems, and that Australian non-forest ecosystems (Types I and II as shown in Fig. 1 include grassland, savanna, woody savanna, shrubland and cropland) accounted for 57% of global terrestrial carbon uptake during the very wet year of 2010/20111,2. These results are supported by remote sensing based estimates of vegetation biomass change over this period (estimated to be 0.05 Pg C year−1) in semi-arid savannas and shrublands of Australia and southern Africa3. Compared with temperate and tropical forest ecosystems in the world, these non-forest ecosystem generally are much less productive, and their significant contributions to both the trend and IAV of global terrestrial carbon uptake were unexpected. The underlying mechanisms driving this large contribution are not well resolved.

Distribution and definition of climate (Köppen-Geiger) and biome (IGBP land cover) space across Australia (total area = 7.56 × 106 km2). Type I is non-forest and semi-arid ecosystems (77.6% of total area). Type II is non-forest and not semi-arid (18.8%). Type III is forested ecosystems and not semi-arid (3.5%). Combination of Type I and II is defined as non-forest ecosystems in our study. Solid points are locations of the 23 flux sites across Australia. Map was drawn using R version 3.2.4 (http://www.R-project.org/).

Net ecosystem production (NEP) is a small difference between two large fluxes, namely gross primary production (GPP) and ecosystem respiration (Re). Identifying the main drivers of these component carbon fluxes (GPP and Re) is critical for understanding the global carbon cycle, predicting future trajectories for atmospheric CO2 concentration and therefore climate change. At an inter-annual scale, variation of NEP substantially depends on the variability of climatic drivers and the different responses of GPP and Re to those drivers4. GPP was found to be more sensitive to drought events than Re 5. Globally, annual rainfall and mean annual temperature drive much of the inter-annual variability in GPP and Re 6,7,8, particularly for non-forest ecosystems. For example decrease in rainfall after 2011 resulted in the the savanna ecosystems in central Australia switching from a strong sink to a weak source of C9. Furthermore, previous studies found that the net ecosystem carbon balance of Australian non-forest ecosystems was principally driven by year-to-year fluctuations in rainfall via changes in both ecosystem GPP and Re 10,11,12.

Australia is the driest permanently inhabited continent on Earth, and is dominated by non-forest ecosystems. To identify the key mechanisms controlling the IAV of NEP for Australian terrestrial ecosystems, we analyzed carbon fluxes from 23 Australian eddy flux sites, which together covered all major Australian ecosystem types13. This study will identify the key mechanisms causing interannual variability in terrestrial ecosystem C balances of Australian forest and non-forest ecosystems, and assess whether those mechansims are correctly represented by some of the most advanced global land models. To achieve the second aim, we also compared the observed variances of log-transformed GPP, LAI, GPP/LAI and the covairnace between log-transformed LAI and GPP/LAI with the simulations from four process-based ecosystem models from the TRENDY (Trends in net land-atmosphere carbon exchange) compendium14.

Results

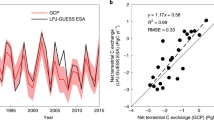

Contrasting sensitivities of non-forest and forest ecosystems to rainfall

We first calculated the anomalies of annual flux variables (ΔGPP, ΔRe and ΔNEP) by subtracting each annual mean value from the multi-annual mean of each ecosystem type (non-forest or forest ecosystem, see Table 1). The range of ΔGPP and ΔRe anomalies of the non-forest ecosystems were 2.22 and 1.47 times larger than their respective values of forest ecosystems (Fig. 2a). This was despite the fact that the range in precipitation anomalies for non-forest (−800~1400 mm) was smaller thant that for forest (−1200~4000 mm). The linear correlation between ΔRe and ΔGPP anomalies was significant for the non-forest ecosystems (ΔRe = 0.76ΔGPP, r 2 = 0.93, P < 0.001), but not significant (we took P < 0.05 as significant) for the forest ecosystems (ΔRe = 0.2ΔGPP, r 2 = 0.004, P = 0.29, Fig. 2a). ΔNEP were significantly and positively correlated with ΔGPP for both non-forest (ΔNEP = 0.24ΔGPP, r 2 = 0.55, P < 0.001) and forest (ΔNEP = 0.8ΔGPP, r 2 = 0.36, P < 0.001) ecosystems (Fig. 2b). ΔNEP was significantly and positively correlated with ΔRe for non-forest ecosystems (ΔNEP = 0.22ΔRe, r 2 = 0.29, P < 0.001) but negatively correlated with ΔRe for forest ecosystems (ΔNEP = −0.82ΔRe, r 2 = 0.42, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2c). Therefore GPP and Re are positively correlated, and they together affect the internnual variation of NEP in non-forest ecosystems. However GPP and Re are not significantly correlated, and they affect NEP independently in forest ecosystems (Fig. 2).

The relationships between annual anomalies of carbon flux anomalies from from the mean of all sites for each ecosystem type in Australia. (a) The correlation between gross primary production (GPP) and ecosystem respiration (Re). (b) The correlation between net ecosystem production (NEP) and GPP. (c) The correlation between NEP and Re. Anomalies were calculated as the annual fluxes minus the mean value of annual fluxes at all sites for each ecosystem type. Red and green solid circles denoted the flux anomalies for non-forest and forest ecosystems, respectively. The solid lines (red for non-forest and green for forest) are the best-fitted linear regression equations with the shaded area for 95% confidence intervals.

The different correlations among the component carbon fluxes between non-forest and forest ecosystems are important for identifying the different key driver of interannual variations of NEP. Among all climatic variables in Australia, coefficient of variation of annual rainfall is greatest. Both ΔGPP and ΔRe were positively and significantly correlated with Δrainfall (r 2 = 0.58, P < 0.001 for ΔGPP and r 2 = 0.60, P < 0.001 for ΔRe, Fig. 3a) in non-forest ecosystems but not significantly in forest ecosystems. Sensitivity of GPP to rainfall anomalies (slope of linear regression equal to 0.96 gC m−2 mm−1 H2O) for the non-forest ecosystems was larger than that for Re (0.78 gC m−2 mm−1H2O), although the difference was not statistically different (P = 0.09).

Responses of gross primary production (GPP) or ecosystem respiration (Re) anomalies to rainfall anomalies for non-forest (a) and forest (b) ecosystems in Australia. Open circles and triangles represent GPP and Re anomalies, respectively. The dashed and dotted lines represent the best-fitted linear regressions between the anomalies of annual GPP or Re and rainfall anomalies, and the red or green regions represent 95% confidence intervals. Ecosystems tended to be source when annual rainfall was below the multi-year mean, or a sink otherwise. Site measured rainfall were used in the analysis.

Because of the systematically greater sensitivity of ΔGPP to rainfall than ΔRe to rainall and high correlation between ΔGPP and ΔRe for non-forest ecosystem, ΔRe/ΔGPP is relatively conservative (0.79 ± 0.54), and ΔNEP is also found to increase significantly with an increase in rainfall for non-forest ecosystems (see Fig. 3a). Therefore the non-forest ecosystems are stronger carbon sink (more positive NEP) when annual rainfall is above the multi-year mean, (see Fig. 3a). For forest ecosystems, we found no significant correlation between ΔGPP, or ΔRe or ΔNEP with rainfall (ΔGPP = −0.05ΔRainfall, r 2 = 0.04, P = 0.13 and ΔRe = 0.05ΔRainfall, r 2 = 0.03, P = 0.16, see Fig. 3b), and the ratio of ΔRe/ΔGPP is quite variable (−0.34 ± 1.89), therefore NEP (carbon sink or source) was independent of inter-annual variation in rainfall.

The response of canopy LAI to rainfall anomalies

Because of the high and positive correlation between GPP and Re, and GPP and NEP for the non-forest ecystems, we consider that Re is largely limited by carbon substrate and that NEP is largely driven by the variation of GPP for non-forest ecosystems. To analyse the variation of GPP for both non-forest and forest ecosystems, we further decompose GPP into GPP per unit LAI and LAI to determine which component, GPP/LAI or LAI dominates the variation of GPP. For non-forest ecosystems by normalizing each variable within its range. That method was previously used to study NEP anomalies1. We found that GPP/LAI and LAI was not significantly correlated (r 2 = 0.009, P = 0.18), and variation of GPP was largely related to both LAI (with a slope of 0.88, r 2 = 0.75, P < 0.001) and GPP/LAI (with a slope of 0.86 and r2 = 0.33, P < 0.001, see Table 2). In contrast, neither GPP/LAI nor LAI per se were significantly correlated with GPP anomalies (r 2 = 0, P = 0.27 for GPP/LAI and r 2 = 0, P = 0.33 for LAI, r 2 = 0.78, P < 0.001 for GPP/LAI and LAI, see Table 2), as a result of the significant and negative correlation between GPP/LAI and LAI (with a slope of −0.84 and r 2 = 0.78, P < 0.001, see Table 2) for forest ecosystems. Furthermore, rainfall anomalies explained 49% of LAI anomalies for non-forest ecosystems (P < 0.001, see Table 2). Because the sensitivity of LAI to rainfall was large and significant for non-forest ecosystems (slope = 0.84, P < 0.001) but not significant in forest ecosystems (slope = 0.09, P = 0.53), we conclude that the main mechanism controlling inter-annual variations of GPP in non-forest ecosystems is the rainfall driven large variation in canopy LAI and to less extent in GPP/LAI.

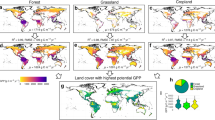

Comparing the observed and simulated mechanisms by the TRENDY models

To quantify the contributions of GPP/LAI and LAI to the variance of GPP, we used the log-tranformation, ie log(GPP) = log(GPP/LAI) + log(LAI). Therefore var(log(GPP)) can be further decomposed into the contributions by the variations of log(GPP/LAI) and log(LAI) and their covariance using the observations from 23 flux towers in Australia or the four TRENDY14 model simulations for both non-forest and forest ecosystems in Australia.

On average the TRENDY models failed to reproduce the dominant role of LAI in controlling GPP IAV for non-forest ecosystems (Fig. 4a) and overestimated the variances of log(LAI), log(GPP/LAI) and their covariance for forest ecosystems by more than 100% (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, the observed covariance between log(LAI) and log(GPP/LAI) was positive, and only contributed about 15% of the variance of log(GPP) in non-forest ecosystems, whereas the covariance of the modelled (log(GPP/LAI) and log(LAI) is negative and nearly as large as the total variance of log(GPP) and log(LAI) for the non-forest ecosystems (Fig. 4a). As a result, the variance of the modelled log(GPP) is only 9% of the variance of the observed log(GPP). The contribution of the covariance of the observed log(GPP/LAI) and log(LAI) to the variance of the observed log(GPP) is different, i.e. negative for non-forest ecosystems and positive for forest ecosystems. This observed difference between non-forest and forest ecosystem was not correctly simulated by the TRENDY models. (see Fig. 4).

Discussion

Most Australian non-forest ecosystems are shrublands and savannas that together significantly contributed to the IAV of global land carbon uptake over the last three decades1. Recent studies demonstrated that the Australian non-forest ecosystems are well adapted to the climate conditions with highly variable rainfall15,16. This study has further demonstrated that it is the rapid response of canopy LAI, and to much less extent the response of GPP/LAI that is the dominant the large contribution of Australian non-forest ecosystems to global land sink IAV. It can be very difficult to quantify the contributions of GPP/LAI and LAI to the variance of GPP if GPP/LAI and LAI are strongly correlated, as for the forest ecosystems in this study. For non-forest ecosystems, the correlation between GPP/LAI and LAI is quite weak (r2 = 0.009, p = 0.18), then decomposing GPP as the product of GPP/LAI and LAI allows us to identify whether GPP/LAI or LAI dominate the variation of GPP.

The dominant role of rainfall in controlling GPP of non-forest ecosystems in Australia was consistent with previous studies on semiarid ecosystems in Africa17,18,19,20 and South America21. Rainfall IAV in non-forest ecosystems (mostly in semi-arid or arid regions) are typically proportionally larger than those experienced in forest ecosystems (in wet regions)22 and we have shown that this also is true at the global scale using Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) data for 2001–2013 (Fig. S1). Large IAV of rainfall in Australia resuls from strong interactions amongst El Niño–southern oscillation, the Indian Ocean dipole and the southern annular mode9,23,24, and will likely intensity under future warmer conditions25. Therefore the non-forest ecosystems in Australia and other parts of the world will likely continue playing a significant role in the global carbon cycle and interannual variation in the growth rate of atmospheric CO2 concentration into the future.

In Australian non-forest ecosystems, both GPP and Re were highly sensitive to rainfall, which drove the ecosystem towards being a carbon sink in wetter years, and conversely, a source in drier years. The non-forest ecosystems can respond to large rainfall events during dry period by rapidly initiating leaf flush and leaf expansion (hence increased LAI), and increasing soil N mineralisation to supply nutrients. As result, photosynthesis (GPP) is enhanced. Rainfall-induced increases in canopy LAI and GPP also increase ecosystem autotrophic respiration (both growth and maintenance respiration). Furthermore increases in available soil moisture and soil nutrients arising from increased soil mineralizationstimulate heterotrophic respiration (soil microbial respiration)26. This interpretation is clearly supported by the strong correlation between annual Re and rainfall in the non-forest ecosystems (Fig. 2b), and is also consistent with observations globally10,11,12. A previous analysis of observations from 238 flux sites found that GPP was about 50% more sensitive to a drought event than Re 5, and that difference is larger than the observed from the non-forest systems in this study. However, if only the flux data for OSH (open shrubland) are used, the difference in the responses of GPP and Re to drought as estimated from the global dataset by Schwalm et al.5 is quite similar to our finding here. For forest ecosystems, Schwalm et al. found a very weak and no sensitivity of GPP or Re to drought, which is also consistent with our results (Fig. 3b).

In Australia, non-forest ecosystems encompass almost all of the mesic savanna and shrubland ecosystems, and these ecosystems have higher levels of available N than forest ecosystems, but only when soil is wet26. This rainfall-driven fluctuation in available soil N, together with increased soil moisture during wet periods, result in a tight coupling between GPP, Re and NEP. As a result, the NEP of the grassland component in savanna and shrubland ecosystems is highly dependent on rainfall9. In contrast, forest ecosystems in Australia occur in regions with less seasonally varying and higher rainfall and do not respond IAV of rainfall as strongly as non-forest ecosystem. In addition, forests have deep root systems which access deep soil moisture reserves and/or groundwater and hence maintain moderate LAI and GPP during relatively dry years27,28,29. Further, forests have multi-annual leaf life spans30, which might account for the lack of response to IAV in rainfall. That is why there was no significant correlation of rainfall with LAI, GPP nor NEP for the Australian forest ecosystems.

Canopy LAI is determined by not only climatic variables (e.g. rainfall) but alo likely the increasing atmospheric CO2. FACE (Free-Air CO2 Enrichment) experiments have found that canopy LAI increased under higher CO2 for some forest species31. Modelling studies also concluded that increase in CO2 reduced stomatal conductance and caused increase in GPP and LAI, particularly in water limited environments32. Limited by short time span, effects of CO2 change on canopy LAI and GPP were not considered in our analyses here, and will be taken into account in future studies. In addition, fire disturbance can be another important factor influencing Australian net ecosystem exchange and inter-annual variation at multiple scales from leaf to landscape33. While the significantly different responses of carbon fluxes to rainfall have been identified between forest and non-forest ecosystem in Australia, interaction of rainfall variation with other elements of the ecosystem (e.g. herbivory) and disturbance (e.g. fire) have not been explored here, and should be considered when accounting Australian terrestrial net biome exchange and their inter-annual variation34.

The four state-of-the-art process-based global land models from TRENDY did not correctly simulate the different responses of LAI to interannual variation of rainfall between forest and non-forest ecosystems, they were unable to predict correctly the dominated role of LAI in contronling GPP IAV for non-forest ecosystems, and overestimated the magnitudes of IAV of log-transformed GPP, LAI, GPP/LAI and the covariance between the latter two variables for Australian forest ecosystems. Importantly, the TRENDY model simulated similar covariance betweeon log(LAI) and log(GPP/LAI) across both non-forest and forest ecosystems, whereas the observed covariance are different in sign between these two types of ecosystems (Fig. 4). This suggests that state-of-the-art process-based ecosystem models as currently structured, need further improvement for forest ecosystems. Explaining the differential responses of ecosystem production to canopy dynamics and rainfall anomalies amongst non-forest and forest ecosystems should be targeted as a high priority in future model improvement, particularly when these models are used to project the trend and IAV in terrestrial ecosystem carbon status.

Methods

Eddy covariance flux observations

We used observations from 23 flux tower sites within the OzFlux network13 (http://www.ozflux.org.au). This dataset consists of 126 site-years data across most major ecosystems types in Australia. All flux data were gap-filled using an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model35. An ANN model was also used to estimate daytime Re from night-time observations of ecosystem respiration. GPP was calculated as the difference between NEP and Re, but these are not independently derived. Further information about the 23 flux towers is provided in Table 1. Original field-based flux data were at a half-hour time-step, and were aggregated to annual values f all correlation analysis.

TRENDY simulations

Four models (Table 3), with available LAI and carbon fluxes (GPP, Re and NEP) from the latest version of the TRENDY project14 were used in this study. The four models used were CABLE36, CLM37, LPJ38, and VISIT39 (Table 2). We used the S2 simulations wherever a time-invariant pre-industrial land use mask40 was applied.

TRENDY model results were used to simulate how carbon fluxes of terrestrial ecosystems respond to changes in climate and atmospheric concentrations of CO2. All four models were operated at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°, and covered the period 1901 to 2013. To match the period of flux tower measurements, model results during 2001–2013 were used in this study.

Satellite datasets

LAI data were obtained from the MOD15A2.005 product of 0.05° × 0.05° spatial resolution and monthly time resolution (http://e4ftl01.cr.usgs.gov/MOLT/MOD15A2.005/), and aggregated to yearly value for analysis. A 3 km by 3 km window centred on the flux tower of each site was used to approximate the footprints of flux towers. Missing values of LAI were filled using the singular spectrum analysis (SSA) method41.

Classification of ecosystems

The MODIS land cover type product (http://e4ftl01.cr.usgs.gov/MOTA/ MCD12C1.051) at a spatial resolution of 0.05° by 0.05° in 2012 was used for classifying the 14 sites into different ecosystem types. First, we classified Australian ecosystems into six biomes based on the MODIS IGBP land cover map for 2012. These six biomes are: evergreen broadleaf (EBF), cropland (CRO), grassland (GRA), savanna (SAV), woody savanna (WSA) and shrubland (OSH). Then all EBF were defined as forest ecosystems and non-EBF biomes were defined as non-forest ecosystems. Water bodies, wetland, urban and other built-up areas, bare or sparsely vegetated land areas were ignored. Our defined non-forest ecosystems (Type I and II, Fig. 1) had an 81% overlap area with those ecosystems in arid or semi-arid climatic zones as defined using the Köppen-Geiger method42 (Fig. 1).

Climate data

Monthly rainfall data at a spatial resolution of 0.05° by 0.05° were obtained from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (http://www.bom.gov.au/jsp/awap/). Annual rainfall was calculated as the sum of monthly rainfall.

References

Poulter, B. et al. Contribution of semi-arid ecosystems to interannual variability of the global carbon cycle. Nature 509, 600–603 (2014).

Ahlström, A. et al. The dominant role of semi-arid ecosystems in the trend and variability of the land CO2 sink. Science 348, 895–899 (2015).

Liu, Y. Y. et al. Recent reversal in loss of global terrestrial biomass. Nature Clim Change 5, 470–474 (2015).

Kanniah, K. D., Beringer, J. & Hutley, L. B. Environmental controls on the spatial variability of savanna productivity in the Northern Territory, Australia. Agric For Meteorol 151, 1429–1439 (2011).

Schwalm, C. R. et al. Assimilation exceeds respiration sensitivity to drought: A FLUXNET synthesis. Global Change Biol 16, 657–670 (2010).

Le Quéré, C. et al. Global carbon budget 2014. Earth Syst Sci Data Discuss 7, 521–610 (2014).

Yi, C. et al. Climate control of terrestrial carbon exchange across biomes and continents. Environmental Research Letters 5 (2010).

Seddon, A. W. R., Macias-Fauria, M., Long, P. R., Benz, D. & Willis, K. J. Sensitivity of global terrestrial ecosystems to climate variability. Nature 531, 229–232 (2016).

Cleverly, J. et al. Productivity and evapotranspiration of two contrasting semiarid ecosystems following the 2011 global carbon land sink anomaly. Agric For Meteorol 220, 151–159 (2016).

Ma, S., Baldocchi, D. D., Hatala, J. A., Detto, M. & Curiel Yuste, J. Are rain-induced ecosystem respiration pulses enhanced by legacies of antecedent photodegradation in semi-arid environments? Agric For Meteorol 154–155, 203–213 (2012).

Jenerette, G. D., Scott, R. L. & Huxman, T. E. Whole ecosystem metabolic pulses following precipitation events. Funct Ecol 22, 924–930 (2008).

Fan, Z., Neff, J. C. & Hanan, N. P. Modeling pulsed soil respiration in an African savanna ecosystem. Agric For Meteorol 200, 282–292 (2015).

Beringer, J. et al. An introduction to the Australian and New Zealand flux tower network - OzFlux. Biogeosciences Discuss 2016, 1–52 (2016).

Sitch, S. et al. Recent trends and drivers of regional sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Biogeosci 12, 653–679 (2015).

Haverd, V., Smith, B. & Trudinger, C. Dryland vegetation response to wet episode, not inherent shift in sensitivity to rainfall, behind Australia’s role in 2011 global carbon sink anomaly. Global Change Biol 22, 2315–2316 (2016).

Vanessa, H., Benjamin, S. & Cathy, T. Process contributions of Australian ecosystems to interannual variations in the carbon cycle. Environmental Research Letters 11, 054013 (2016).

Williams, C. A. et al. Interannual variability of photosynthesis across Africa and its attribution. J Geophys Res - Biogeosci 113 (2008).

Zhu, L. & Southworth, J. Disentangling the Relationships between Net Primary Production and Precipitation in Southern Africa Savannas Using Satellite Observations from 1982 to 2010. Remote Sensing 5, 3803 (2013).

Guan, K. et al. Seasonal coupling of canopy structure and function in African tropical forests and its environmental controls. Ecosphere 4, art35 (2013).

Ciais, P., Piao, S. L., Cadule, P., Friedlingstein, P. & Chédin, A. Variability and recent trends in the African terrestrial carbon balance. Biogeosci 6, 1935–1948 (2009).

Brando, P. M. et al. Seasonal and interannual variability of climate and vegetation indices across the Amazon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 14685–14690 (2010).

Knapp, A. K. & Smith, M. D. Variation Among Biomes in Temporal Dynamics of Aboveground Primary Production. Science 291, 481–484 (2001).

Cleverly, J. et al. The importance of interacting climate modes on Australia’s contribution to global carbon cycle extremes. Sci Rep 6, 23113 (2016).

Rogers, C. & Beringer, J. Describing rainfall in northern Australia using multiple climate indices. Biogeosciences Discuss 2016, 1–39 (2016).

Cai, W. et al. Increased frequency of extreme La Nina events under greenhouse warming. Nature Clim Change 5, 132–137 (2015).

Soper, F. M. et al. Natural abundance (δ15N) indicates shifts in nitrogen relations of woody taxa along a savanna–woodland continental rainfall gradient. Oecologia 178, 297–308 (2015).

Smettem, K. R. J., Waring, R. H., Callow, J. N., Wilson, M. & Mu, Q. Satellite-derived estimates of forest leaf area index in southwest Western Australia are not tightly coupled to interannual variations in rainfall: implications for groundwater decline in a drying climate. Global Change Biol 19, 2401–2412 (2013).

Li, L et al. Improving the responses of the Australian community land surface model (CABLE) to seasonal drought. J Geophys Res 117 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multi-decadal trends in global terrestrial evapotranspiration and its components. Sci Rep 6, 19124 (2016).

Wright, I. J. & Westoby, M. Leaves at low versus high rainfall: coordination of structure, lifespan and physiology. New Phytol 155, 403–416 (2002).

Norby, R. J. & Zak, D. R. Ecological Lessons from Free-Air CO2 Enrichment (FACE) Experiments. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 42, 181–203 (2011).

Macinnis-Ng, C., Zeppel, M., Williams, M. & Eamus, D. Applying a SPA model to examine the impact of climate change on GPP of open woodlands and the potential for woody thickening. Ecohydrology 4, 379–393 (2011).

Beringer, J. et al. Fire in Australian savannas: from leaf to landscape. Global Change Biol 21, 62–81 (2015).

Hutley, L. B. et al. Impacts of an extreme cyclone event on landscape-scale savanna fire, productivity and greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental Research Letters 8, 045023 (2013).

Beringer, J., Hutley, L. B., Tapper, N. J. & Cernusak, L. A. Savanna fires and their impact on net ecosystem productivity in North Australia. Global Change Biol 13, 990–1004 (2007).

Wang, Y. P., Law, R. M. & Pak, B. A global model of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles for the terrestrial biosphere. Biogeosci 7, 2261–2282 (2010).

Lawrence, D. M. et al. Parameterization improvements and functional and structural advances in Version 4 of the Community Land Model. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 3, M03001 (2011).

Sitch, S. et al. Evaluation of ecosystem dynamics, plant geography and terrestrial carbon cycling in the LPJ dynamic global vegetation model. Global Change Biol 9, 161–185 (2003).

Akihiko, I. & Motoko, I. Water-Use Efficiency of the Terrestrial Biosphere: A Model Analysis Focusing on Interactions between the Global Carbon and Water Cycles. Journal of Hydrometeorology 13, 681–694 (2012).

Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of land-use scenarios for the period 1500–2100: 600 years of global gridded annual land-use transitions, wood harvest, and resulting secondary lands. Clim Change 109, 117–161 (2011).

Alexandrov, T. A method of thrend extraction using singular spectrum analysis. Revstat-Statistical Journal 7, 1–22 (2009).

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B. & Rubel, F. World map of the Koppen-Geiger climate classification updated. MetZe 15, 259–263 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by an ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award project (DE120103022). JB is funded by an ARC Future Fellowship (FT110100602). Support for collection and archiving was provided through the Australia Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (TERN) (http://www.tern.org.au). Collection of flux tower data used in this paper were supported by the Australian Research Council (DP0344744, DP0772981, LE0882936, DP0451247 and DP130101566).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.H.L. and Y.P.W. contributed to design this study. J.B., Y.P.W., D.E. and L.H.L. co-wrote the manuscript. H.S., X.J.L. and L.C. performed the analysis. J.B. provided a large portion of flux data. S.L.P., J.B., L.H., J.C., Q.Y., A.H., L.Z., and Y.Q.Z. contributed significantly to the discussion of results, manuscript refinement and provision of EC data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Wang, YP., Beringer, J. et al. Responses of LAI to rainfall explain contrasting sensitivities to carbon uptake between forest and non-forest ecosystems in Australia. Sci Rep 7, 11720 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11063-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11063-w

This article is cited by

-

Automated predictive analytics tool for rainfall forecasting

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Ungulates Attenuate the Response of Mediterranean Mountain Vegetation to Climate Oscillations

Ecosystems (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.