Abstract

Late Permian Karoo Basin tectonics in South Africa are reflected as two fining-upward megacycles in the Balfour and upper Teekloof formations. Foreland tectonics are used to explain the cyclic nature and distribution of sedimentation, caused by phases of loading and unloading in the southern source areas adjacent to the basin. New data supports this model, and identifies potential climatic effects on the tectonic regime. Diachronous second-order subaerial unconformities (SU) are identified at the base and top of the Balfour Formation. One third-order SU identified coincides with a faunal turnover which could be related to the Permo-Triassic mass extinction (PTME). The SU are traced, for the first time, to the western portion of the basin (upper Teekloof Formation). Their age determinations support the foreland basin model as they coincide with dated paroxysms. A condensed distal (northern) stratigraphic record is additional support for this tectonic regime because orogenic loading and unloading throughout the basin was not equally distributed, nor was it in-phase. This resulted in more frequent non-deposition with increased distance from the tectonically active source. Refining basin dynamics allows us to distinguish between tectonic and climatic effects and how they have influenced ancient ecosystems and sedimentation through time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Karoo Basin of South Africa represented a large depocenter situated in southern Gondwana supported by the Kaapvaal Craton in the northeast and the Namaqua-Natal Metamorphic Belt (NNMB) in the southwest1, 2. Deposition and accumulation in the Karoo Basin began with the Dwyka Group (320–280 Ma)3, followed by the Ecca, Beaufort, and Stormberg groups respectively, finally terminating after more than 100 Million years of sedimentation with the igneous basaltic outpourings of the early Jurassic Drakensberg Group1, 4,5,6,7,8,9. Theories on the origin of accommodation in the Karoo Basin and distance from the Paleo-Pacific subduction zone (>1500 km)10 and Gondwanan Mobile Belt (GMB) include, activation of the Southern Cape Conductive Belt, a crustal geophysical anomaly11, fault-controlled subsidence2, 12, and continent-continent collision with south dipping subduction zone13. Despite disagreements, most workers recognize foreland basin tectonics with a north dipping subduction zone in the Karoo basin and it is only the timing of the onset of foreland tectonics that has been seriously disputed. It is now clear that by the time of deposition of the Dwyka Group, foreland tectonics were already operating3, 14,15,16. Thus the Karoo Basin was most likely a foreland basin from its formation and these conditions continued until its termination at the end of the Stormberg Group1, 17. Additionally, northward thinning of strata, condensed, diachronous, and missing lithostratigraphic units away from the source area reflects many characteristics of modern foreland systems18,19,20,21,22. Thus, foreland tectonics, with dynamic subsidence resulting from orogenic loading by flat-slab subduction23, 24, is currently the most popular explanation for the generation of accommodation in the main Karoo Basin1, 3, 5, 10, 16, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34.

Flexural tectonics partitioned the Karoo Basin into the foredeep, forebulge, and backbulge flexural provinces with a dominantly southerly sediment source area1, 4. Orogenic loading and unloading in the GMB changed the forebulge and foredeep’s positions, and this resulted in deposition in the proximal basin in the south during loading and distal regions of the Karoo Basin in the north during unloading. Where a time lag occurred between orogenic loading and basinal subsidence24, 26 the upper and lower boundaries of lithostratigraphic units are diachronous, and have proximal and distal equivalents. Thus, many of the upper and lower boundaries of lithostratigraphic groups are diachronous or have proximal and distal equivalents1, 4, 35. This is reflected in the geologic record as the preservation of large-scale (second-order) fining upward depositional sequences bounded by subaerial unconformities (SU)1, 36, 37. Thus the SU in this study were identified by relatively abrupt changes in lithology (e.g. renewed fining upward cycles), mean change in paleocurrent direction, changes in fluvial style (e.g. from high to low sinuosity), and rarely by palaeoclimatic changes and faunal turnover38.

Modern and ancient foreland basins like the Karoo Basin are bounded by tectonically active source areas. Episodic tectonic activity results in the rejuvenation of fluvial systems leading to deposition of coarser sediment, and cessation in tectonic activity results in an overall fining upward sequence37. These cycles are recognized in the Beaufort Group39 by fluvial systems that are characterized by an initial pulse of high energy fluvial transport (e.g. sandstone-rich lithological unit), often underlain by an SU, followed by increasingly finer grained sediment as tectonic activity ceased1 and river gradients declined. Similarly, this cyclicity is used to identify the position of SUs in Upper Cretaceous fluvial deposits in southern Utah40, 41.

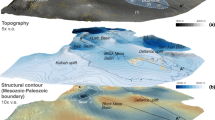

The most recent sequence stratigraphic research on the Beaufort Group’s Balfour Formation identified six, unconformity-bound third-order depositional sequences within a 2150 m interval36, which are the result of smaller-scale orogenic events. Recently, the Late Permian Beaufort Group stratigraphy has been revised42, 43 (Fig. 1). This study reviews the tectonic setting of the Late Permian Karoo Basin and uses sequence stratigraphy to provide an updated basin development model. It also discusses the implications of our increased understanding of Late Permian Karoo Basin dynamics and how to recognize the climatic overprint on foreland basin sequences.

(A) Map of South Africa’s Karoo Basin showing local geology and position of the field sites. The field sites are near Gariep Dam (GD), Cradock (CR), Nieu Bethesda (NB), and Beaufort West (BW). (B) Current lithostratigraphic subdivisions of strata correlated to the Daptocephalus and Lystrosaurus assemblage zones. All cartographic information was reported by PAV and by referring to written literature cited from35, 66,67,68. All this information was reproduced by PAV using Inkscape (vers. 0.91, https://inkscape.org/en/release/0.91/platforms/).

Results

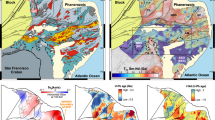

Composite sections of the four field sites (Fig. 2), and a suggested basin model for the Late Permian Karoo Basin (Fig. 3) present the results. The composite sections document two fining-upward sequences in the Balfour and upper Teekloof formations. Our study also identifies three subaerial unconformities (SU) using the criteria outlined previously (Fig. 2). Two second-order SUs are present at the base and top of the Balfour Formation1 and one third-order SU is noted in the middle of the Balfour Formation, which only attains a maximum thickness of 513 m. This contradicts previous observations on the sequence stratigraphy of the Balfour Formation, whose six third-order SU over a 2150 m stratigraphic interval36 are based only on estimated Late Permian lithostratigraphic thicknesses44, 45. Our study extends the second-order SU at the base of the Balfour Formation west to the base of the Oukloof Member (upper Teekloof Formation) and northwards towards the basin’s forebulge (Figs 2 and 3), updates biostratigraphic ranges, and absolute dates46, 47 show the SU are diachronous. Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone tetrapod fauna provide further evidence for out-of-phase sedimentation because they occur in different lithostratigraphic units in different parts of the foreland system. From absolute dates which constrain their stratigraphic distribution in the eastern basin, the conclusion can be made that the SU boundaries are older in the western part of the basin (Fig. 2).

Composite sections created for the field sites of this study. Faunal ranges of Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone index taxa are shown in conjunction with stratigraphic position of low and high sinuosity fluvial systems, second-order and third-order subaerial unconformities (SU), palaeocurrents, and absolute dates. The migration of this SU east and northwards fits with observations made from faunal ranges that uppermost Permian stratigraphic succession is more complete in the south than in the north of the basin. All vertical and cartographic information was recorded and reproduced by PAV and reproduced using Inkscape (vers. 0.91, https://inkscape.org/en/release/0.91/platforms/).

(A) Sequence stratigraphic framework for the Late Permian-Lower Triassic Karoo Basin in relationship to new paroxysm dates61 and the stratigraphic hinge line1. Thick wavy lines depict the second-order sequence boundaries (SU). Thinner wavy lines indicate a third-order SU. (B) Schematic models for the evolution of the Karoo Basin during Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone times in the Late Permian to Lower Triassic. Letters represent field sites Beaufort West (B), Cradock (C), Nieu Bethesda (N), Gariep Dam (G). Proximal represents the entire foredeep in this diagram and distal is the back bulge. The Cape Fold Belt (CFB) represents the source of sediment and tectonic activity south of the basin. Numbered 1–4, the basin schematics depict changes in orogenic loading and unloading and the effect this had creation of accommodation in the Karoo foreland basin. All information was reported and reproduced by PAV using Inkscape (vers. 0.91, https://inkscape.org/en/release/0.91/platforms/).

Discussion

Although some of the SU presented in this study have been observed in the Karoo Basin by previous workers1, 34, 36, 48,49,50, they were interpreted as having a purely tectonic origin as uplift leads to increased stream gradients, sediment input, and accommodation proximal to the source area1, 36. However, climatic, and tectonic signatures are shown to overprint one another during the onset and aftermath of the Permo-Triassic mass extinction event (PTME)51,52,53,54,55,56,57. This study provides some evidence that climatic changes associated with the PTME were occurring much lower in the stratigraphy than previously documented. Thus it is concluded the third-order tectonic SU could be overprinted by these palaeoclimatic changes. This is supported by a newly identified faunal turnover and abundance changes marked by the appearance of Lystrosaurus maccaigi and disappearance of Dicynodon lacerticeps, Theriognathus microps, and Procynosuchus delaharpeae in this SU. Palaeoclimatic changes at the point of the third-order SU in the Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone are identified by a decrease in the occurrence of subaqueous environments in the overbank facies42. In addition, distal attenuation of the Balfour Formation towards the north indicates there was more accommodation for sediment proximally, and point to more non-deposition distally during the Late Permian42, 43. Although this faunal turnover is not identified at the base of the SU in the Beaufort West field site, it implies that the third-order SU is diachronous. Diachroneity has been identified at major lithostratigraphic boundaries of the Karoo Supergroup, such as the Ecca-Beaufort contact, Katberg-Burgersdorp contact, and Burgersdorp-Molteno contact1, 58,59,60 and is evidence of tectonic influences controlling sediment distribution in the foredeep.

New Tectonic Model

All evidence collected indicates that cyclic, out-of-phase sedimentation in the Karoo Basin during the Late Permian resulted from a strong tectonic influence south of the basin which was also the source of clastic material. Our depositional model refines third-order detail in addition to the mostly first and second-order framework of the Karoo Basin sedimentary fill1, 36. Each second or third-order sequence correlates to an orogenic cycle of thrusting followed by unloading. New paroxysm dates61 fall within the dates of known active orogenic loading.

It is interesting to note that although out-of-phase, the western and eastern basin (Teekloof and Balfour formations) show similar lithostratigraphic sequences and it is clear they were influenced by similar tectonic and climatic events in the basin (Fig. 3). The western and eastern sectors of the Karoo Basin could represent two distinct Distributive Fluvial Systems (DFS)62, 63 and the geophysically- defined “Willowmore arch”64, which is interpreted as a palaeotopographic high, was present between these two parts of the basin. This may explain some differences between the two parts of the basin but essentially, they are reflecting similar tectonic events in the foreland system defined by fairly repetitive, and roughly synchronous, depositional cycles37. This also entertains the possibility of alternative controls on subsidence that caused the basin to contain down-warped depressions and upward arches formed by the interplay of the foreland compressional tectonics and local rheology and structural integrity of the basement rocks. The Kaapvaal Craton situated below the distal basin would have been more rigid and buoyant than the Namaqua-Natal Metamorphic Belt which comprises the basement rocks of the proximal foredeep and back bulge. Structural anomalies could have controlled tectonics locally2, 65, and may have contributed to the out-of-phase deposition created by flexural tectonics of the foreland system. This study’s basin model has four stages which explain the inferred tectonic setting of the Late Permian Karoo Basin (Fig. 3).

Stage 1 Follows orogenic uplift in the Gondwanide Mobile Belt with the onset of sedimentation of the Balfour in the southeast and upper Teekloof formations in the southwest of the basin which began at the base of the first second-order SU and represents the beginning of a fining-upward cycle deposited by low sinuosity rivers (the eastern Oudeberg and western Oukloof members). Distally, there was non-deposition as no lithostratigraphic equivalent is documented close to the forebulge. Once sediment supply became less than available accommodation, the sequence began to fine-upward, depositing argillaceous material by high sinuosity rivers (the eastern Daggaboersnek and western Steenkampsvlakte members).

Another minor orogenic loading event initiated stage 2, resulting in the out-of-phase deposition of the arenaceous Javanerskop member in the west and Ripplemead member in the east above the third-order SU. On current biostratigraphic evidence43, the Javanerskop member appears to be slightly older than the Ripplemead member and is present only in the south east and central Karoo Basin. Coincidently, the decrease in sinuosity of the fluvial systems leads to reduced overbank preservation, and disappearance of lacustrine systems.

Stage 3 is an unloading phase resulting in distal progradation of sediment when accommodation became available in the distal foredeep. This explains the attenuated but similar stratigraphy. The third-order sequence began to fine upwards, terminating in the argillaceous Elandsberg and Palingkloof members (Figs 2 and 3). This sequence was overprinted by climatic changes during the onset of the PTME55 as indicated by paleoclimatic changes and a newly identified faunal turnover. Stage 4 marks the beginning of deposition of the early Triassic lower Katberg Formation during a new orogenic loading phase.

Conclusions

Flexural tectonics imposed phases of orogenic loading and unloading during the Late Permian Karoo Basin. This was the major control on the distribution of accommodation in the foredeep of the Karoo Basin as demonstrated by northward thinning wedge-shaped deposition of strata and cyclic sedimentation bounded by two second-order, and one third-order subaerial unconformities (SU)37, 40, 41, 62, 63. Foreland tectonics meant that progradation of sediment northwards (distal foredeep) during orogenic loading and unloading was not in phase with the south (proximal foredeep) which resulted in an incomplete and attenuated stratigraphic record to the north, and diachronous SU between the west and eastern parts of the basin.

Throughout the depositional cycle of the Late Permian Beaufort Group, little evidence for significant climatic change has been documented1, 34, 36, but tectonic and climatic signals are notoriously difficult to tease apart in the geologic record27, 37. The revised Late Permian stratigraphy and tectonics42, 43 indicate that there was some climatic change overprinting the tectonic signatures imposed by orogenic loading1 at least by the Upper Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone (DaAZ), and the third-order SU, as fauna began to go extinct or decrease in abundance42, 43. This new basin model, in combination with revised Late Permian stratigraphic investigations, tells us that environmental changes may have been occurring earlier than previously documented and they could be related to the effects of the PTME55. Thus, understanding ancient ecosystems has important implications for the understanding basin dynamics, especially in the Late Permian Karoo Basin where there is much evidence for a coeval terrestrial counterpart to the global Permo-Triassic mass extinction (PTME)51, 53, 55,56,57. There is still much debate concerning what role tectonics and climate played in this major biotic crisis, and studies such as this contribute to understanding this important event in Earth’s history.

Methods and Materials

The study area encompassed the stratigraphic range of the Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone (Balfour and upper Teekloof formations). Four field sites were chosen near Cradock, Nieu Bethesda, Beaufort West, and Gariep Dam (Fig. 1). Numerous fossils were collected and stratigraphically recorded. Vertical sections measured compiled four composite sections, one for each field site. This was done to investigate Late Permian Karoo Basin litho, bio, and sequence stratigraphy. This research also required referral to research conducted by previous workers to corroborate findings36, 54.

References

Catuneanu, O., Hancox, J. P. & Rubidge, B. S. Reciprocal flexural behaviour and contrasting stratigraphies: A new basin development model for the Karoo retroarc foreland system, South Africa. Basin Research 10, 417–439 (1998).

Tankard, A. J., Welsink, H., Aukes, P., Newton, R. & Stettler, E. Tectonic evolution of the Cape and Karoo basins of South Africa. Marine and Petroleum Geolology 26, 1379–1412 (2009).

Catuneanu, O. Retroarc foreland systems–evolution through time. Journal of African Earth Sciences 38, 225–242 (2004).

Catuneanu, O. et al. The Karoo basins of south-central Africa. Journal of African Earth Sciences 43, 211–253 (2005).

Cole, D. I. Evolution and development of the Karoo Basin. Inversion tectonics of the Cape Fold Belt, Karoo and cretaceous basins of Southern Africa. 87–99 (1992).

Duncan, R. A., Hooper, P. R., Rehacek, J. & Marsh, J. S. The timing and duration of the Karoo igneous event, southern Gondwana. Journal of Geophysical Research 138, 127–138 (1997).

South African Committee for Stratigraphy. Geological Survey of South Africa Handbook (eds Kent, L. E) Ch. 8, 1–690 (1980).

Smith, R. M. H., Eriksson, P. G. & Botha, W. J. A Review of the Stratigraphy and Sedimentary Environments of the Karoo-Aged Basins of Southern Africa. Journal of African Earth Sciences 16, 143–169 (1993).

Tankard, A. J. et al. Crustal evolution of southern Africa: 3.8 Billion Years of Earth History. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Pysklywec, R. N. & Mitrovica, J. X. The role of subduction-induced subsidence in the evolution of the Karoo basin. Journal of Geology 107, 155–164 (1999).

De Wit, M. J., Jeffery, M., Bergh, H. & Nicholaysen, L. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Publications (1988).

Turner, B. R. Tectonostratigraphical development of the Upper Karoo foreland basin: Orogenic unloading versus thermally-induced Gondwana rifting. Journal of African Earth Sciences 28, 215–238 (1999).

Lindeque, A., De Wit, M. J., Ryberg, T., Weber, M. & Chevallier, L. Deep crustal profile across the southern Karoo Basin and Beattie Magnetic Anomaly, South Africa: an integrated interpretation with tectonic implications. South African Journal of Geology 114, 265–292 (2011).

Bordy, E. M. & Catuneanu, O. Sedimentology and palaeontology of upper Karoo aeolian strata (Early Jurassic) in the Tuli Basin, South Africa. Journal of African Earth Sciences 35, 301–314 (2002).

Bordy, E. M. & Catuneanu, O. Sedimentology of the lower Karoo Supergroup fluvial strata in the Tuli Basin, South Africa. Journal of African Earth Sciences 35, 503–521 (2002).

Isbell, J. L., Cole, D. I. & Catuneanu, O. Carboniferous-Permian glaciation in the main Karoo Basin, South Africa: Stratigraphy, depositional controls, and glacial dynamics. Geological Society of America Special Papers 441, 71–82 (2008).

Bordy, E. M., Hancox, P. J. & Rubidge, B. S. Basin development during the deposition of the Elliot Formation (Late Triassic-Early Jurassic), Karoo Supergroup, South Africa. South African Journal of Geology 107, 397–412 (2004).

DeCelles, P. G. & Cavazza, W. A comparison of fluvial megafans in the Cordilleran (Upper Cretaceous) and modern Himalayan foreland basin systems. Geological Society of America Bulletin 111, 1315–1334 (1999).

DeCelles, P. G. & Giles, K. A. Foreland basin systems. Basin Research 8, 105–123 (1996).

Gibling, M., Tandon, S., Sinha, R. & Jain, M. Discontinuity-bounded alluvial sequences of the southern Gangetic Plains, India: aggradation and degradation in response to monsoonal strength. Journal of Sedimentary Research 75, 369–385 (2005).

Horton, B. & DeCelles, P. G. Modern and ancient fluvial megafans in the foreland basin system of the central Andes, southern Bolivia: Implications for drainage network evolution in fold‐thrust belts. Basin Research 13, 43–63 (2001).

Horton, B. K. & DeCelles, P. G. The modern foreland basin system adjacent to the Central Andes. Geology 25, 895–898 (1997).

Catuneanu, O., Beaumont, C. & Waschbusch, P. Interplay of static loads and subduction dynamics in foreland basins: Reciprocal stratigraphies and the “missing” peripheral bulge. Geology 12, 1087–1090 (1997).

Mitrovica, J. X., Beaumont, C. & Jarvis, G. T. Tilting of continental interiors by the dynamical effects of subduction. Tectonics 8, 1079–1094 (1989).

Catuneanu, O. Sequence stratigraphy of clastic systems: concepts, merits, and pitfalls. Journal of African Earth Sciences 35, 1–43 (2002).

Catuneanu, O. Basement control on flexural profiles and the distribution of foreland facies: The Dwyka Group of the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Geology 32, 517–520 (2004).

Catuneanu, O. Principles of sequence stratigraphy, First edition. (Elsevier, 2006).

Le Roux, J. P. Heartbeat of a mountain: diagnosing the age of depositional events in the Karoo (Gondwana) Basin from the pulse of the Cape Orogen. Geologische Rundschau 84, 626–635 (1995).

Lock, B. E. Flat-plate subduction and the Cape Fold Belt of South Africa. Geology 8, 35–39 (1980).

Miall, A. D., Catuneanu, O., Vakarelov, B. K. & Post, R. The Western interior basin. Sedimentary basins of the world 5, 329–362 (2008).

Uličný, D. Sequence stratigraphy of the Dakota Formation (Cenomanian), southern Utah: interplay of eustasy and tectonics in a foreland basin. Sedimentology 46, 807–836 (1999).

Visser, J. N. J. Deposition of the Early to Late Permian Whitehill Formation during a sea-level highstand in a juvenile foreland basin. South African Journal of Geology 95, 181–193 (1992).

Visser, J. N. J. Sea-level changes in a back-arc-foreland transition: the late Carboniferous-Permian Karoo Basin of South Africa. Sedimentary Geology 83, 115–131 (1993).

Visser, J. N. J. & Dukas, B. A. Upward-fining mega-cycles in the Beaufort Group, north of Graaff-Reinet, Cape Province. Transactions of the Geological Society of South Africa. 82, 149–154 (1979).

Rubidge, B. S. et al. Biostratigraphy of the Beaufort Group (Karoo Supergroup). 1–46 (Biostratigraphic series 1, 1995).

Catuneanu, O. & Elango, H. N. Tectonic control on fluvial styles: the Balfour Formation of the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Sedimentary Geology 140, 291–313 (2001).

Catuneanu, O. et al. Sequence stratigraphy: Methodology and nomenclature. Newsletters on Stratigraphy 43/3, 173–245 (2011).

Miall, A. D. & Arush, M. Cryptic sequence boundaries in braided fluvial successions. Sedimentology 48, 971–985 (2001).

Le Roux, J. P. Genesis of stratiform U-Mo deposits in the Karoo Basin of South Africa. Ore Geology Reviews 7, 485–509 (1993).

Shanley, K. W. & McCabe, P. J. Perspectives on the sequence stratigraphy of continental strata. AAPG bulletin 78, 544–568 (1994).

Shanley, K. W. & McCabe, P. J. AAPG special volumes: Memoir 64 (eds J. C., Van Wagoner & G. T., Bertram) 103–136 (1995).

Viglietti, P. A., Rubidge, B. S. & Smith, R. M. H. Revised lithostratigraphy of the Upper Permian Balfour and Teekloof formations of South Africa’s Karoo Basin. South African Journal of Geology. *Accepted (2016).

Viglietti, P. A. et al. The Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone (Lopingian), South Africa: A proposed biostratigraphy based on a new compilation of stratigraphic ranges. Journal of African Earth Sciences 113, 153–164 (2016).

Johnson, M. R. South African code of stratigraphic terminology and nomenclature. (Geological Survey of South Africa, 1996).

Johnson, M. R. & Keyser, A. W. Explanatory notes. 1: 250 000 Geological Series 3226 King Williams Town. Government Printer, Pretoria (1976).

Gastaldo, R. A. et al. Is the vertebrate-defined Permian-Triassic boundary in the Karoo Basin, South Africa, the terrestrial expression of the end-Permian marine event? Geology 43, 1–5 (2015).

Rubidge, B. S., Erwin, D. H., Ramezani, J., Bowring, S. A. & de Klerk, W. J. High-precision temporal calibration of Late Permian vertebrate biostratigraphy: U-Pb zircon constraints from the Karoo Supergroup, South Africa. Geology 10, 1–4 (2013).

Johnson, M. R. Stratigraphy and sedimentology of the Cape and Karoo sequences in the Eastern Cape Province. (Masters dissertation 1966).

Johnson, M. R. Stratigraphy and sedimentology of the Cape and Karoo sequences in the Eastern Cape Province. (Doctoral dissertation 1976).

Smith, R. M. H. Fluvial facies, vertebrate taphonomy, and palaeosols of the Teekloof Formation (Permian) near Beaufort West, Cape Province, South Africa. (Doctoral dissertation 1989).

Botha, J. & Smith, R. M. H. Rapid vertebrate recuperation in the Karoo Basin of South Africa following the End-Permian extinction. Journal of African Earth Sciences 45, 502–514 (2006).

Hiller, N. & Stavrakis, N. Permo-Triassic fluvial systems in the southeastern Karoo basin, South Africa. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 45, 1–21 (1984).

Smith, R. M. H. Changing fluvial environments across the Permian-Triassic boundary in the Karoo Basin, South Africa and possible causes of tetrapod extinctions. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 117, 81–104 (1995).

Smith, R. M. H. & Botha, J. The recovery of terrestrial vertebrate diversity in the South African Karoo Basin after the end-Permian extinction. Comptes Rendus Palevol 4, 623–636 (2005).

Smith, R. M. H. & Botha-Brink, J. Anatomy of a mass extinction: sedimentological and taphonomic evidence for drought-induced die-offs at the Permo-Triassic boundary in the main Karoo Basin, South Africa. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 396, 99–118 (2014).

Smith, R. M. H. & Ward, P. D. Pattern of vertebrate extinctions across an event bed at the Permian-Triassic boundary in the Karoo Basin of South Africa. Geology 29, 1147–1150 (2001).

Viglietti, P. A., Smith, R. M. H. & Compton, J. Origin and palaeoenvironmental significance of Lystrosaurus bonebeds in the earliest Triassic Karoo Basin, South Africa. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 392, 9–21 (2013).

Hancox, P. J. A Stratigraphic, sedimentological and palaeoenvironmental synthesis of the Beaufort–Molteno contact, in the Karoo Basin. (Doctoral dissertation 1998).

Neveling, J. Biostratigraphic and sedimentological investigation of the contact between the Lystrosaurus and Cynognathus Assembalge Zones (Beaufort Group; Karoo Supergroup). (Doctoral dissertation 2002).

Rubidge, B. S., Hancox, J. P. & Catuneanu, O. Sequence analysis of the Ecca-Beaufort contact in the southern Karoo of South Africa. South African Journal of Geology 103, 81–96 (2000).

Hansma, J., Tohver, E., Schrank, C., Jourdan, F. & Adams, D. The timing of the Cape Orogeny: New 40 Ar/39 Ar age constraints on deformation and cooling of the Cape Fold Belt, South Africa. Gondwana Research (2015).

Weissmann, G. S. et al. Fluvial form in modern continental sedimentary basins: distributive fluvial systems. Geology 38, 39–42 (2010).

Weissmann, G. S. et al. Fluvial geomorphic elements in modern sedimentary basins and their potential preservation in the rock record: A review. Geomorphology 250, 187–219 (2015).

Van Eeden, O. R. The Geology of the Republic of South Africa: An Explanation of the 1 1000 000 Map, 1970 Edition. Vol. 18, 1–85 (Government Printer, South Africa 1972).

Tankard, A. J., Welsink, H., Aukes, P., Newton, R. & Stettler, E. Phanerozoic passive margins, cratonic basins and global tectonic maps (eds Roberts, D. G., Bally, A. W.) 869–945 (Elsevier, 2012).

Cole, D. I. et al. The Geology of the Middelburg Area. Explanation sheet 3124 (scale: 1:250 000). (2004).

Cole, D. I. & Wipplinger, P. E. Sedimentology and molybdenum potential of the Beaufort Group in the main Karoo basin, South Africa. (Geological Survey of South Africa 2001).

Kitching, J. W. The distribution of the Karroo vertebrate fauna. Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research Memoir 1 (1977).

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by financial support from the Palaeontological Scientific Trust (PAST) and its Scatterlings of Africa programmes, as well as the African Origins platform of the National Research Foundation (NRF) ((AOGR)UID¼826103). The support of the DST/NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences (CoE in Palaeosciences) towards this research is hereby acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.A.V., B.S.R., R.M.H. wrote the article. P.A.V. conducted the investigation and all fieldwork.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Viglietti, P.A., Rubidge, B.S. & Smith, R.M.H. New Late Permian tectonic model for South Africa’s Karoo Basin: foreland tectonics and climate change before the end-Permian crisis. Sci Rep 7, 10861 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09853-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09853-3

This article is cited by

-

The base of the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone, Karoo Basin, predates the end-Permian marine extinction

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Mesozoic deposits of SW Gondwana (Namibia): unravelling Gondwanan sedimentary dispersion drivers by detrital zircon

International Journal of Earth Sciences (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.