Abstract

Spiral waves are shown to undergo directional drifts in the presence of ac and polarized electric fields when their frequencies are twice of the spiral frequencies. Here, we propose a quantitative description for the spiral wave drift induced by weak electric fields, and provide the explicit equations for the spiral wave drift speed and direction. Numerical simulations are performed to demonstrate the quantitative agreement with analytical results in both weakly and highly excitable media.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Excitable media represent a wide class of nonequilibrium systems which play an important role in physical, chemical, and biological applications1, 2. Spiral waves are among the most paradigmatic examples of spatiotemporal self-organizing structures in excitable media, such as cardiac tissue3, 4, aggregations of Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae5, the oxidation of CO on platinum6, and the Belousov-Zhabotinsky (BZ) reaction7. In cardiology, such self-sustained spiral wave activities play an essential role in cardiac arrhythmia and fibrillation8,9,10,11,12,13. This, with the intrinsic interest of those structures, has led to an important research effort in order to understand the dynamic of spiral waves.

The BZ reaction is the most extensively studied system which supports spiral waves. The authors in ref. 14 reported the first experimental observation of a directional drift of the spiral wave along a straight line, during the periodic modulation of the excitability of an excitable medium with a frequency close to the nature rotation frequency of the spiral. This directional drift phenomenon for spiral waves subjected to the external periodic forcing has been confirmed in numerous experiments as well as numerical simulations. And its mechanism has also been studied in refs. 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Based on the case of a weakly excitable medium, an initial mathematical treatment of the directional drift for rigidly rotating spiral waves under a periodic forcing was provided23. This approach is based on a kinematic model of spiral dynamics in which one disregards the thickness of the excited area, and models the spiral as a one-dimensional curve. In ref. 24, the periodic forcing of spiral waves was considered from a dynamically systematic view point. It was shown that much of the spiral behavior could be deduced simply from the interaction of dynamics with system symmetries. In ref. 25, an asymptotic derivation of a kinematic theory for the spiral wave motion in the weakly excitable and free-boundary limit was presented. The mechanism of the directional drift of spiral waves subjected to the external periodic forcing was studied and a drift velocity formula for spirals was obtained. In refs. 26,27,28, the directional drift for rigidly rotating spiral waves under the periodic forcing was studied by using the response function theory for both weak and high excitabilities.

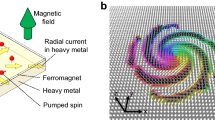

In the presence of a dc electric field, spiral waves in the BZ reaction drift with a velocity whose two components are parallel and perpendicular to the applied field29, 30. The component of the drift perpendicular to the electric field changes its sign with chirality of the spiral wave. A numerical study31 showed that depending on the parameter regime, the drift direction of the spiral could be either parallel (with small core) or antiparallel (with large core) to the dc electric field. The small core corresponds to highly excitable media, and the large core to weakly excitable media. The mechanism of the spiral drift by dc electric fields has been studied25, 31,32,33,34,35,36. However, most analytical studies are restricted to the weak or high excitability limit. By using the response function theory of spiral waves, the drift of spirals by dc electric fields was studied28, 37, 38. The theoretical results are quantitatively consistent with the numerical ones for both weak and high excitabilities. The theory was first proposed for the autonomous dynamics of scroll waves in the case of small curvatures and twists39, 40, and then extended to the drift of spiral waves in response to small perturbations26. Recently, an efficient numerical method of calculating response functions has been presented in an arbitrary model with differentiable right-hand sides27, 41. By using the response function theory, the drift laws for spiral waves on curved anisotropic surfaces were investigated. And an asymptotic theory that predicts the drift of spiral waves on general curved surfaces with the anisotropic diffusion has been developed42. The response function theory has also been used to study the change of the filament tension for scroll waves caused by a circularly polarized electric field43.

Spiral waves in the BZ reaction undergo a directional drift when the frequency of an ac electric field is twice that of the spiral frequency44. The direction of the spiral drift changes continuously between 0 and 2π when the initial rotation phase of the spiral varies from 0 to π. A kinematical model for spirals subjected to a strong ac electric field was proposed on a phenomenological basis45. This kinematical model has succeeded in capturing many aspects of the drift of spiral waves induced by strong ac electric fields. However, it has not been derived from the underlying reaction-diffusion equations. Thus, its parameters need to be adjusted, and cannot be obtained from the underlying reaction-diffusion equation. And the drift of spiral waves induced by weak ac electric fields has been studied from a theoretical point of view25, 46. But an analytical and quantitative explanation for this mechanism is needed.

Recently, a polarized electric field that possesses chirality was theoretically proposed47 and has been implemented in the BZ experiment48. It allows us to study the response of spiral waves to a chiral electric field. The drift behavior of spiral waves under the influence of a polarized electric field was investigated numerically. An analytical derivation which neglects the deformation of the spiral is consistent with the numerical results qualitatively47. However, an analytical derivation which takes account of the deformation for this mechanism is still lacking. Analytical results directly from the reaction diffusion equation are of importance, for a deeper understanding of the mechanism of the drift and a wider application of the spiral wave control.

In this paper, we derive the drift velocities of spiral waves due to weak ac and polarized electric fields using the response function theory, and compare the analytical results with the velocities obtained in direct numerical simulations for both weak and high excitabilities. The detailed forms of electric fields are shown in Table 1.

Results

The theory of wave propagation in excitable media in the presence of an electric field \(\overrightarrow{E}=({E}_{x},{E}_{y})\) can be described by reaction diffusion equations,

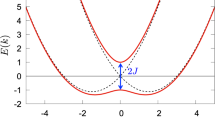

where u = [u, v]T, \({\bf{F}}({\bf{u}})={[f(u,v),g(u,v)]}^{T}\), and \(\mathop{{\bf{D}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}\) and \(\mathop{{\bf{M}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}\) are constant matrices. In this paper, we use the FitzHugh-Nagumo kinetics49, 50, i.e., \(f(u,v)=(u-{u}^{3}/3-v)/\varepsilon \) and \(g(u,v)=\varepsilon (u+\beta -\gamma v)\). \(\mathop{{\bf{D}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}\) and \(\mathop{{\bf{M}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}\) are both set to be \((\begin{array}{cc}1 & 0\\ 0 & 0\end{array})\). Throughout this work, we choose a set of parameter values as ε = 0.22, β = 0.58, and γ = 0.8, such that the medium is highly excitable (see Fig. 1(a)). In the weakly excitable one, parameters are chosen as ε = 0.22, β = 0.78, and γ = 0.8 (see Fig. 1(b)). The spiral tip is defined as the intersections of two isolines of u = 0 and v = 0.

In the absence of electric fields, a rigidly rotating spiral wave solution to Eq. (1) is in the form of

where \(\overrightarrow{R}\) is the center of rotation, Φ is the initial rotation phase, ω > 0 is the angular frequency, and \(\rho (\overrightarrow{r}-\overrightarrow{R})\) and \({\vartheta }(\overrightarrow{r}-\overrightarrow{R})\) are polar coordinates centered at \(\overrightarrow{R}\). The spiral tip whose position vector is \({\overrightarrow{\zeta }}_{tip}(t)\) rotates in a circle centered at \(\overrightarrow{R}\). Without loss of generality, we choose the angle between \({\overrightarrow{\zeta }}_{tip}(t=0)\) and the positive x axis as the initial rotation phase Φ, which is measured counterclockwise from the positive x axis. The rotation direction is determined by the chirality σ, i.e. σ = +1 for the counterclockwise rotating spiral and σ = −1 for the clockwise one51, 52.

Derivation of the drift equations

In the following, without loss of generality, we only consider the drift of the clockwise rotating spiral, which can be easily extended to study the drift of the counterclockwise rotating spiral. It is convenient that the drift velocity of the spiral is analyzed in the system of reference of the spiral, i.e. the system of reference corotating with the spiral’s initial phase and angular velocity ω around the spiral’s center of rotation. In this system of reference, the polar angle is given by \(\theta ={\vartheta }+\omega t-{\rm{\Phi }}\), with \(\overrightarrow{R^{\prime} }=\mathop{0}\limits^{\rightharpoonup }\) and Φ′ = 0. According to the response function theory26, a small perturbation \(-\mathop{{\bf{M}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}\overrightarrow{E}\cdot \overrightarrow{\nabla }{\bf{u}}\) acts on a rigidly rotating spiral by causing translational and rotational shifts. In particular, a solvability condition leads to the following equation for the drift velocity of the spiral:

where \(R(t)=X+iY\) is the complex coordinate of the instant spiral center, and \(\dot{R}(t)\) is the drift velocity. The inner product 〈w, v〉 stands for the scalar product in the functional space in the system of reference of the spiral (Φ′ = 0)

and W (1) is one of the response functions of the spiral. Mathematically, it is the eigenfunction of the adjoint linearized operator corresponding to the critical eigenvalue −iω.

To study the directional drift of spirals, it is convenient to average the motion of the spiral over the rotation period. After the central moving average over the spiral wave rotation period, the drift velocity can be expressed as

\(\dot{R}\) can also be written as \(\dot{R}=|\dot{R}|{e}^{i{\rm{\Theta }}}\), where \(|\dot{R}|\) is the drift speed, and Θ the drift direction. In Eq. (3b), \(\mathop{{\bf{M}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}\overrightarrow{E}\cdot \overrightarrow{\nabla }{\bf{U}}=\mathop{{\bf{M}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}{E}_{x}{\partial }_{x}{\bf{U}}+\mathop{{\bf{M}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}{E}_{y}{\partial }_{y}{\bf{U}}\). It follows that

where

are two of the Goldstone modes of the spiral, i.e. the eigenfunctions of the linearized operator corresponding to the critical eigenvalues iω and −iω, respectively. Substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (3b), we obtain finally

Thus a drift velocity formula in terms of the electric fields, the response functions, the Goldstone modes, and the initial rotation phase of the spiral is given.

For simplicity, we write the resultant as

such that \(|\dot{R}|\) and Θ can be explicitly written. In Table 2, we compute the drift coefficients μ 1, v 1, μ 2, and v 2 for both weak and high excitabilities using the open source software “DXSpiral”41.

DC electric fields

From the general drift velocity formula in Eq. (5), we first discuss the case of dc electric fields. When a dc electric field is applied, only the first component in Eq. (5) contributes to the directional drift of the spiral. And the drift velocity reads as

Substitution of Eq. (6) into Eq. (8) gives the drift speed and direction as

From Table 2, one can calculate the theoretical predictions in two excitabilities as \({|\dot{R}|}_{weak}={\rm{0.008413}},\) \({{\rm{\Theta }}}_{weak}={\rm{3.999}}\) and \({|\dot{R}|}_{high}={\rm{0.004284}},\,{{\rm{\Theta }}}_{high}={\rm{6.211}}\), respectively. And from the direct numerical simulations (see Fig. 1(c) and (d)), we get \({|\dot{R}|}_{weak}={\rm{0.008415}},\,{{\rm{\Theta }}}_{weak}={\rm{4.004}}\) and \({|\dot{R}|}_{high}={\rm{0.004276}},\,{{\rm{\Theta }}}_{high}={\rm{6.209}}\) for the two excitabilities, respectively. Quantitative differences between theoretical predictions and numerical simulations are relatively small. The relative differences are less than 0.2% for both weak and high excitabilities. Equation (9) shows that both \(|\dot{R}|\) and Θ are independent of the initial rotation phase Φ. This is also observed in numerical simulations. Note that the drift equations of spirals by dc electric fields in Eqs (8) and (9) are identical to the results obtained in refs. 28, 37, 38.

AC electric fields

The spiral wave undergoes a directional drift in the presence of an ac electric field when ω e = 2ω (see Fig. 2(a) and (b)). In this resonant case, the drift velocity in Eq. (5) becomes

First row: Trajectories of spiral tips movement under the influence of an ac electric field with ω e = 2ω, ϕ e = 0, and Φ = 0. Second row: Drift speed as a function of Φ with ϕ e = 0. Third row: Drift angle as a function of Φ with ϕ e = 0. In the second and the third rows, the circles represent numerical simulations and the lines represent theoretical predictions. Left column: Highly excitable medium. Right column: Weakly excitable medium.

Using Eq. (7), one obtains

From above equations, we can draw following conclusions about the resonant drift induced by ac electric fields, which are independent of the special models. Firstly, the drift speed \(|\dot{R}|\) is independent of the initial rotation phase Φ of the spiral and the initial phase ϕ e of the ac electric field, which are confirmed by direct numerical simulations in Figs 2(c),(d) and 3(a) and (b). The analytically obtained values \(|\dot{R}|\) agree well with the ones obtained by simulations in both weakly and highly excitable media. Secondly, for the fixed ϕ e , the drift direction Θ changes continuously when the initial rotation phase Φ varies. And Θ is linear in Φ. The change of Θ is twice as much as that of Φ, i.e., ΔΘ = 2ΔΦ. Thus ΔΘ = 2π if ΔΦ = π. This means that the drift direction Θ keeps invariant when the change of Φ is π. The analytical values Θ are quantitatively consistent with the numerical simulations, as shown in Fig. 2(e) and (f). Thirdly, for the fixed Φ, the spiral drifts in different directions when we change ϕ e , but the change of Θ is equal to that of ϕ e , i.e., ΔΘ = Δϕ e . Numerical simulations are performed to demonstrate the quantitative agreement with the analytically obtained values Θ in both weakly and highly excitable media, as shown in Fig. 3(c) and (d). Note that the numerical and theoretical results of the spiral drift induced by strong ac electric fields in refs. 44 and 45 showed that \(|\dot{R}|\) does depend on Φ, and Θ is not linear in Φ. The reason is clear. Since in refs. 44 and 45 E 0 is equal to 2.0, but in our case E 0 is 0.005. According to the response function theory, the analytical results obtained in this paper are valid for weak electric fields. On the other hand, the relation between Θ and ϕ e was not studied in refs. 44 and 45. Thus, further laboratory works on the spiral drift induced by weak ac electric fields are expected. We note that spiral wave fronts may break above some electric field threshold53.

Drift velocity as a function of ϕ e in the presence of an ac electric field with ω e = 2ω and Φ = 0. Top row: Theoretical (lines) and numerical (circles) drift speed vs ϕ e . Bottom row: Theoretical (lines) and numerical (circles) drift angle vs ϕ e . Left column: Highly excitable medium. Right column: Weakly excitable medium.

Polarized electric fields

The general drift velocity formula in Eq. (5) can also be applied to the case of polarized electric fields. In the resonant case (ω e = 2ω), the spiral drifts along a straight line, and the drift velocity reads as

Substituting Eq. (7) into Eq. (12), one can obtain

A significant feature predicted in Eq. (13) is that when the electric field is circularly polarized and its rotation follows that of the spiral (ϕ xy = 0.5π), the drift speed \(|\dot{R}|\) reaches its maximal value. On the contrary, opposite rotation between the spiral and electric field (ϕ xy = 1.5π) locks the spiral. This prediction is confirmed by numerical simulations, and the analytically obtained values \(|\dot{R}|\) are quantitatively consistent with the ones obtained by simulations, as shown in Fig. 4(a–d). And the drift direction Θ changes continuously when Φ or ϕ e varies. Their relations are ΔΘ = 2ΔΦ and ΔΘ = Δϕ e , which are the same results as in ac electric fields. Moreover, the spirals drift in different directions when we change the phase difference ϕ xy , and the change of the drift direction is half as much as that of the phase difference, i.e., ΔΘ = 0.5Δϕ xy . This unexpected prediction is also confirmed by direct numerical simulations, and the analytical values Θ agree well with the numerical ones, as shown in Fig. 4(e,f).

First row: Drifting behaviors of spirals under the influence of a clockwise (ϕ xy = 0.5π) and a counterclockwise (ϕ xy = 1.5π) circularly polarized electric fields with ω e = 2ω, ϕ e = 0, and Φ = 0. Second row: Dependence of theoretical (lines) and numerical (circles) drift speed on ϕ xy with ϕ e = 0 and Φ = 0. Third row: Dependence of theoretical (lines) and numerical (circles) drift angle on ϕ xy with ϕ e = 0 and Φ = 0. When the drift speed is 0 (ϕ xy = 1.5π), the drift angle cannot be defined. Left column: Highly excitable medium. Right column: Weakly excitable medium.

In conclusion, we have studied the drift of spiral waves induced by weak electric fields analytically, since analytical results are of crucial importance for a deeper and more comprehensive understanding to the mechanism of the spiral wave drift. Using the response function theory, we propose a theory of the spiral wave drift due to weak ac and polarized electric fields. Explicit equations for the spiral wave drift speed and direction in terms of Φ, E 0, ϕ e , and ϕ xy are obtained directly from the reaction diffusion equations, which are independent of the special models and should be of general significance. These analytical results are quantitatively confirmed by numerical simulations in both weakly and highly excitable media. Although ac electric fields44 and polarized electric fields48 have been realized in the BZ system, laboratory works on the spiral drift induced by weak ac and polarized electric fields have not been investigated. We hope that the theoretical results in Eqs (11) and (13) can be verified in experiments.

Methods

In direct numerical simulations of the FitzHugh-Nagumo model in Eq. (1), we use an explicit Euler method and no-flux boundary conditions with the space step at Δx = Δy = 0.05 and time step at Δt = 0.0005 for the grids 500 × 500 in Cartesian coordinate system.

We compute V (1)(Φ′ = 0), V (−1)(Φ′ = 0), and W (1)(Φ′ = 0) using the open source software “DXSpiral”41. Since “DXSpiral” is dealing with spiral waves on a polar grid in a disk, to get a similar precision with Δx = 0.05 in direct numerical simulations, we use a disk of radius at 12.5 with 250 radial and 124 circumferential grid cells. Note that in the computation, the initial rotation phase of the spiral in the system of reference of the spiral should be set to be 0, i.e. Φ′ = 0. In our computations, we find that \(\langle {{\bf{W}}}^{(1)}({\rm{\Phi }}^{\prime} ),\mathop{{\bf{M}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}{{\bf{V}}}^{(-1)}({\rm{\Phi }}^{\prime} )\rangle \) is dependent on Φ′, but \(\langle {{\bf{W}}}^{(1)}({\rm{\Phi }}^{\prime} ),\mathop{{\bf{M}}}\limits^{{\boldsymbol{\frown }}{}}{{\bf{V}}}^{(1)}({\rm{\Phi }}^{\prime} )\rangle \) is not. This is related to the fact that the drift velocity of the spiral induced by the dc electric field does not depend on the initial rotation phase of the spiral, while the drift velocity induced by the ac electric field depends on the initial rotation phase.

References

Winfree, A. T. The Geometry of Biological Time (New York: Springer, 2001).

Zykov, V. S. Modelling of Wave processes in Excitable Media (Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press, 1988).

Davidenko, J. M., Pertsov, A. V., Salomonsz, R., Baxter, W. & Jalife, J. Stationary and drifting spiral waves of excitation in isolated cardiac muscle. Nature (London) 355, 349 (1992).

Gray, R. A., Pertsov, A. M. & Jalife, J. Spatial and temporal organization during cardiac fibrillation. Nature (London) 392, 75 (1998).

Sawai, S., Thomason, P. A. & Cox, E. C. An autoregulatory circuit for long-range self-organization in Dictyostelium cell populations. Nature (London) 433, 323 (2005).

Jakubith, S., Rotermund, H. H., Engel, W., Von Oertzen, A. & Ertl, G. Spatiotemporal concentration patterns in a surface reaction: Propagating and standing waves, rotating spirals, and turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 3013 (1990).

Winfree, A. T. Spiral waves of chemical activity. Science 175, 634 (1972).

Jalife, J. Ventricular fibrillation: Mechanisms of initiation and maintenance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62, 25 (2000).

Cherry, E. M. & Fenton, F. H. Visualization of spiral and scroll waves in simulated and experimental cardiac tissue. New J. Phys. 10, 125016 (2008).

Karma, A. Physics of cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 313 (2013).

Luther, S. et al. Low-energy control of electrical turbulence in the heart. Nature (London) 475, 235 (2011).

Feng, X., Gao, X., Pan, D. B., Li, B. W. & Zhang, H. Unpinning of rotating spiral waves in cardiac tissues by circularly polarized electric fields. Sci. Rep. 4, 04831 (2014).

Qu, Z. L., Hu, G., Garfinkel, A. & Weiss, J. N. Nonlinear and stochastic dynamics in the heart. Phys. Rep. 543, 61 (2014).

Agladze, K. I., Davydov, V. A. & Mikhailov, A. S. Observation of a helical-wave resonance in an excitable distributed medium. JETP Lett. 45, 767 (1987).

Steinbock, O., Zykov, V. & Müller, S. C. Control of spiral-wave dynamics in active media by periodic modulation of excitability. Nature (London) 366, 322 (1993).

Zykov, V., Steinbock, O. & Müller, S. C. External forcing of spiral waves. Chaos 4, 509 (1994).

Braune, M., Schrader, A. & Engel, H. Entrainment and resonance of spiral waves in active media with periodically modulated excitability. Chem. Phys. Lett. 222, 358 (1994).

Schrader, A., Braune, M. & Engel, H. Dynamics of spiral waves in excitable media subjected to external periodic forcing. Phys. Rev. E 52, 98 (1995).

Nettesheim, S., Von Oertzen, A., Rotermund, H. & Ertl, G. Reaction diffusion patterns in the Catalytic Co-oxidation on Pt(110): Front propagation and spiral waves. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 9977 (1993).

Zykov, V. S., Bordiougov, G., Brandtstädter, H., Gerdes, I. & Engel, H. Periodic forcing and feedback control of nonlinear lumped oscillators and meandering spiral waves. Phys. Rev. E 68, 016214 (2003).

Kantrasiri, S., Jirakanjana, P. & Kheowan, O.-U. Dynamics of rigidly rotating spirals under periodic modulation of excitability. Chem. Phys. Lett. 416, 364 (2005).

Xu, L., Li, Z., Qu, Z. & Di, Z. Resonance drifts of spiral waves on media of periodic excitability. Phys. Rev. E 85, 046216 (2012).

Mikhailov, A., Davydov, V. & Zykov, V. Complex dynamics of spiral waves and motion of curves. Physica D 70, 1 (1994).

Mantel, R. M. & Barkley, D. Periodic forcing of spiral waves in excitable media. Phys. Rev. E 54, 4791 (1996).

Hakim, V. & Karma, A. Theory of spiral wave dynamics in weakly excitable media: Asymptotic reduction to a kinematic model and applications. Phys. Rev. E 60, 5073 (1999).

Biktashev, V. & Holden, A. Resonant drift of autowave vortices in two dimensions and the effects of boundaries and inhomogeneities. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 5, 575 (1995).

Biktasheva, I. V., Barkley, D., Biktashev, V. N., Bordyugov, G. V. & Foulkes, A. J. Computation of the response functions of spiral waves in active media. Phys. Rev. E 79, 056702 (2009).

Biktasheva, I. V., Barkley, D., Biktashev, V. N. & Foulkes, A. J. Computation of the drift velocity of spiral waves using response functions. Phys. Rev. E 81, 066202 (2010).

Steinbock, O., Schütze, J. & Müller, S. C. Electric-field-induced drift and deformation of spiral waves in an excitable medium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 248 (1992).

Agladze, K. I. & Kepper, P. D. Influence of electric field on rotating spiral waves in the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction. J. Phys. Chem. 96, 5239 (1992).

Krinsky, V., Hamm, E. & Voignier, V. Dense and sparse vortices in excitable media drift in opposite directions in electric field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3854 (1996).

Muñuzuri, A. P., Gómez-Gesteira, M., Pérez-Muñuzuri, V., Krinsky, V. I. & Pérez-Villar, V. Mechanism of the electric-field-induced vortex drift in excitable media. Phys. Rev. E 48, R3232 (1993).

Mitkov, I., Aranson, I. & Kessler, D. A. Interaction of spiral waves with external fields in excitable media. Phys. Rev. E 52, 5974 (1995).

Wellner, M., Pertsov, A. M. & Jalife, J. Spiral drift and core properties. Phys. Rev. E 59, 5192 (1999).

Di, Z., Qu, Z. L., Weiss, J. N. & Garfinkel, A. A kinematic study of spiral wave drift due to an electric field. Phys. Lett. A 308, 179 (2003).

Wellner, M. Algebraic study of drifting spiral waves. Phys. Rev. E 94, 042421 (2016).

Henry, H. & Hakim, V. Scroll waves in isotropic excitable media: Linear instabilities, bifurcations, and restabilized states. Phys. Rev. E 65, 046235 (2002).

Henry, H. Spiral wave drift in an electric field and scroll wave instabilities. Phys. Rev. E 70, 026204 (2004).

Keener, J. P. The dynamics of three dimensional scroll waves in excitable media. Physica D 31, 269 (1988).

Biktashev, V. N., Holden, A. V. & Zhang, H. Tension of organizing filaments of scroll waves. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. A 347, 611 (1994).

Barkley, D., Biktashev, V. N., Biktasheva, I. V., Bordyugov, G. & Foulkes, A. DXSpiral: A code for studying spiral waves on a disk, http://cgi.csc.liv.ac.uk/~ivb/SOFTware/DXSpiral.html (2010).

Dierckx, H., Brisard, E., Verschelde, H. & Panfilov, A. V. Drift laws for spiral waves on curved anisotropic surfaces. Phys. Rev. E 88, 012908 (2013).

Li, T. C. et al. Phase-locked scroll waves defy turbulence induced by negative filament tension. Phys. Rev. E 93, 012216 (2016).

Muñuzuri, A. P., Gómez-Gesteira, M., Pérez-Muñuzuri, V., Krinsky, V. I. & Pérez-Villar, V. Parametric resonance of a vortex in an active medium. Phys. Rev. E 50, 4258 (1994).

Muñuzuri, A. P., Pérez-Muñuzuri, V., Gómez-Gesteira, M., Krinsky, V. I. & Pérez-Villar, V. Mechanism of parametric resonance of vortices in excitable media. Int. J. Bif. Chaos 4, 1245 (1994).

Deng, L. Y., Zhang, H. & Li, Y. Q. Resonant drift of two-armed spirals by a periodic advective field and periodic modulation of excitability. Phys. Rev. E 81, 016204 (2010).

Chen, J. X., Zhang, H. & Li, Y. Q. Drift of spiral waves controlled by a polarized electric field. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 014505 (2006).

Ji, L., Zhou, Y., Li, Q., Qiao, C. & Ouyang, Q. Experimental evidence of using a circularly polarized electric field to control spiral turbulence. Phys. Rev. E 88, 042919 (2013).

FitzHugh, R. Impulses and physiological states in theoretical models of nerve membrane. Biophys. J. 1, 445 (1961).

Nagumo, J., Arimoto, S. & Yoshizawa, S. An active pulse transmission line simulating nerve axon. Proc. IRE 50, 2061 (1962).

Zhang, H., Hu, B. B., Li, B. W. & Duan, Y. S. Topological constraints on scroll and spiral waves in excitable media. Chin. Phys. Lett. 24, 1618 (2007).

Pan, J. T., Cai, M. C., Li, B. W. & Zhang, H. Chiralities of spiral waves and their transitions. Phys. Rev. E 87, 062907 (2013).

Taboada, J. J., Muñuzuri, A. P., Pérez-Muñuzuri, V., Gómez-Gesteira, M. & Pérez-Villar, V. Spiral breakup induced by an electric field in a Belousov-Zhabotinsky medium. Chaos 4, 519 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We thank V. N. Biktashev for making valuable comments on this manuscript and helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants Nos. 11675141, 11375149, 11447026.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z., X.G., F.F.Z. mostly contributed to the analytical part and T.C.L., B.Z., D.B.P. mostly contributed to the numerical part. T.C.L., X.G., B.Z., H.Z. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, TC., Gao, X., Zheng, FF. et al. A theory for spiral wave drift induced by ac and polarized electric fields in chemical excitable media. Sci Rep 7, 8657 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09092-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09092-6

This article is cited by

-

Influence of a circular obstacle on the dynamics of stable spiral waves with straining

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Termination of a pinned spiral wave by the wave train with a free defect

Nonlinear Dynamics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.