Abstract

The glass forming ability (GFA) of metallic glasses (MGs) is quantified by the critical cooling rate (R C). Despite its key role in MG research, experimental challenges have limited measured R C to a minute fraction of known glass formers. We present a combinatorial approach to directly measure R C for large compositional ranges. This is realized through the use of compositionally-graded alloy libraries, which were photo-thermally heated by scanning laser spike annealing of an absorbing layer, then melted and cooled at various rates. Coupled with X-ray diffraction mapping, GFA is determined from direct R C measurements. We exemplify this technique for the Au-Cu-Si system, where we identify Au56Cu27Si17 as the alloy with the highest GFA. In general, this method enables measurements of R C over large compositional areas, which is powerful for materials discovery and, when correlating with chemistry and other properties, for a deeper understanding of MG formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The glass forming ability (GFA) is most directly quantified by the inverse of the critical cooling rate (R C), the minimum cooling rate required to avoid crystallization upon solidification resulting in vitrification into a fully amorphous state. Despite its significance, R C has only been directly measured for a minute fraction of metallic glass (MG) forming systems1,2,3,4,5,6. The majority of R C quantifications have been estimated using indirect methods. This is due to challenges in experimentally measuring R C, particularly for glass formers with R C exceeding 104 K s−1. Therefore, a method to directly measure R C would be both scientifically and technologically powerful. Even more impactful would be the ability to measure R C over large composition ranges as it would enhance alloy development and provide insight into the mechanistic origins of glass formation.

Strategies to effectively consider large numbers of alloys are based on combinatorial synthesis paired with high-throughput characterization of properties. Such combinatorial strategies, well established in pharmaceutical research7, are relatively new in materials science and particularly MG research. First combinatorial methods applied in MG research include measurements of mechanical properties8,9,10,11, thermophysical properties12,13,14, functional properties15,16,17, thermoplastic formability18, and microstructure evolution11,12,19,20,21. Attempts were made to draw conclusions about GFA from some of those measurements10,12,18,21. More recently approaches to measure GFA directly have been limited in cooling rate, in alloy composition, and generally in versatility21,22,23,24.

In this study, we use a combinatorial approach to directly measure R C across a significant fraction of the composition space in a ternary system. Through indirect laser spike annealing (LSA), we melt and cool co-sputtered alloy libraries over a range of controlled cooling rates. Employing structural and chemical characterization, R C as a function of composition is determined and Au56Cu27Si17 was identified as the alloy with the highest GFA in the Au-Cu-Si system.

Results

Experimental setup for R C measurements using laser heating

To measure R C, the synthesized alloy library must be melted and cooled in a controlled manner. Using LSA as a heating method provides localized, concentrated heat flux with precise control over the heating and cooling profile25,26,27,28, which is ideal for combinatorial studies. However, directly exposing the laser onto an alloy film library can produce inconsistent temperature profiles. This is due to the composition-dependence of the absorption coefficient, which can vary significantly in a ternary system29,30. To avoid associated uncertainty in temperature and cooling rates, the alloy library is heated indirectly (Fig. 1). We realize this by co-sputtering the alloy library onto a substrate that is designed specifically for photo-thermal heating (see Methods). Such a substrate consists of a heat sink that is optically transparent to the laser and a photo-thermal absorbing layer. When the laser impinges on the substrate side, the radiation is transmitted through the heat sink and then absorbed by the absorbing layer, consequently heating the alloy via conduction. Tuning the incident laser heat flux via the laser scan speed determines the temperature profile, hence the cooling rate, experienced by the alloy.

Schematic of the experimental setup for R C measurements via laser spike annealing. We use a CO2 laser with a 60 W continuous wave (CW) maximum output, operating at a wavelength of 10.6 μm. Compatible with this wavelength, intrinsic (undoped) Si, which has low absorption at 10.6 μm32,51, is selected as the heat sink material. For the photo-thermal absorbing layer, we use 30 nm tungsten (W)52, which is electrically insulated with 30 nm Si3N4 to prevent reflective thick film behavior53 from the ~1 μm Au-Cu-Si ternary alloy library. This setup is mounted onto a fixture with adjustable height (z) for laser focus while the laser optics are motorized on two axes (x and y) such that the laser can be delivered to the substrate at known positions and scan speeds. Altering the laser scan speed, in this case v x, varies the temperature profile. The samples are characterized using XRD, OM, and EDS mapping.

Determination of cooling rates

To demonstrate the proposed method, we first chose a film of constant composition Au55Cu25Si20 (Fig. 2)31. Its composition was verified by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). To vary the temperature profiles, the laser translational scan speed (v x in Fig. 1) was systematically changed. X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements, utilizing a beam mask commensurate to the heat affected zone size (2 mm), and optical microscopy (OM) were then carried out ex-situ (Fig. 2). For the slowest scan speed of 0.2 cm s−1, large dendrites are observed (Fig. 2b) indicating melting and slow crystallization during cooling. XRD results reveal that with increasing laser scan speed, the amount of crystallinity and crystal size decreases.

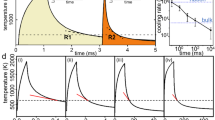

Determination of cooling rates at different laser scan speeds. (a) XRD diffractograms measured from Au55Cu25Si20 films melted using multiple laser scan speeds. With higher scan speeds, the amorphous fraction increases, indicating faster cooling rates with faster scan speeds. (b–f) OM images, with a high magnification inset, of the Au55Cu25Si20 film surface as a function of various laser scan speeds. Scale bars are 250 μm and 25 μm in the insets. For laser scan speeds exceeding 9.2 cm s−1, the features are not clearly resolved by OM. The heat affected zone size is measured from the extent over which the microstructural features are observed in the direction perpendicular to the laser scan. (g) Simulated temperature profiles of laser heating experiments at variable scan speeds. The simulation was fitted with experimental values of the measured heat affected zone size. The T L was taken from measured values of bulk samples of Au55Cu25Si20 31 and T Nose was approximated to be 0.8T L. The inset shows the calculated cooling rate at 0.8T L as a function of laser scan speed.

To quantify the cooling rates for a given laser scan speed and power, simulations of the LSA process were conducted over the range of scan speeds where melting was visually observed and XRD measurements (Fig. 2a) on the remelted region indicated a transition from crystalline to amorphous. These simulations assumed a Gaussian-shaped heat source (see Methods). The laser power and peak width were determined by fitting the heat affected zone size, measured from OM images at different scan speeds (Fig. 2b–f), to produce the most representative simulations. The cooling rates could be extracted from the simulated temperature profiles of a particular point along the laser scan line (Fig. 2g). The cooling rate from the temperature profile that defines R C is the cooling rate at the nose temperature (T Nose) of the time-temperature-transformation (TTT) diagram. Across multiple Au-Cu-Si-based MG chemistries, T Nose is approximately 0.8 times the liquidus temperature (T L)5,6,31. Our simulations reveal a monotonic increase of the cooling rate with the laser scan speed (Fig. 2g inset), which is coupled with the maximum temperature (Fig. 2g). Hence, only scan speeds that result in maximum temperatures exceeding T L are considered. The R C of Au55Cu25Si20 MG is 3.4 × 104 K s−1, as determined from the simulation for a scan speed of 9.2 cm s−1.

It should be noted that the simulations do not consider the temperature-dependence of the absorption coefficient of Si, and therefore can be expected to slightly overestimate the cooling rate. These deviations are relatively low for relevant temperatures, as the optical absorption of Si32 is four orders of magnitude lower than that of W33 at T L of Au55Cu25Si20 (654 K)31.

To ensure that the measured R C reflects the intrinsic behavior of the alloy, one has to consider that at the outline of the heat affected zone resulting from LSA, a solid-liquid interface exists. Here, the unmelted solid could act as a nucleation site during solidification of the melted alloy. Whether or not this situation affects R C measurements away from the interface can be concluded by the size of the solidifying grains, which has to be comparable to the melted zone size in order to significantly influence the observed R C (Fig. 2b–f). This situation is only present at very slow cooling rates (Fig. 2b), much lower than the intrinsic R C. Hence, we can conclude that the measured R C is independent of the heterogeneous nucleation of from the solid-liquid interface, and is an innate property.

GFA as a function of composition

The ultimate goal of the developed method is to determine R C over large compositional regions. To realize such compositional regions, we fabricate compositional libraries by combinatorial co-sputtering from three sputtering guns in a tetrahedral arrangement16,20. Using this method we cover a composition range where Au varies from 32 to 93 at.%, Cu from 5 to 55 at.%, and Si from 1 to 39 at.%. Using EDS and XRD mapping, the composition and structure, respectively, as a function of position on the wafer is determined (Fig. 3). As-sputtered, the entire alloy library experienced a cooling rate of ~1010 K s−1. This is summarized in the Gibbs triangle indicating amorphous and crystalline regions (Fig. 3a). The as-sputtered state represents the fastest cooling rate in this investigation.

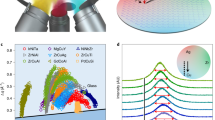

Composition-dependent R C. Gibbs triangles with red circles depicting the fully amorphous state and navy blue circles depicting states with detectable crystalline phases of (a) as-sputtered films, which experienced a cooling rate of 1010 K s−1, and films that have been laser-treated with scan speeds of (b) 11.5 cm s−1, (c) 9.2 cm s−1, and (d) 6.9 cm s−1. Based on temperature profile simulations (Fig. 2g), the R C for the amorphous regions are approximately (b) 5.5 × 104 K s−1, (c) 3.4 × 104 K s−1, and (d) 1.7 × 104 K s−1. (e) By compiling the mapped out regions of the amorphous phase as a consequence of multiple laser scan speeds (a–d), contours of R C as a function of composition can be plotted. The black region represents considered compositions that crystallized, even upon sputtering. The symbols indicate the composition with the highest measured GFA, reported ternary MG compositions with high GFA21,31 and dotted lines indicating a range, reported binary MG compositions36,37, the global eutectic composition34, and the composition with the lowest nucleation temperature12. The compositions in all the Gibbs triangles (a–e) are in at.%.

In order to determine R C for the alloys with potentially the highest GFA in the Au-Cu-Si system, similar laser scan speeds that were used to determine R C of Au55Cu25Si20 (Fig. 2) of 6.9, 9.2, and 11.5 cm s−1 were applied for LSA of the alloy libraries (Fig. 3b–d). The cooling rates near T Nose that the amorphous regions were exposed to are 1.7 × 104 K s−1, 3.4 × 104 K s−1, and 5.5 × 104 K s−1, respectively. For a scan speed of 11.5 cm s−1, the amorphous region shrank significantly in comparison to the one for the as-sputtered data. For example, the maximum of Au variation over which the library remains amorphous reduces from 39 to 66 at.% to 42 to 60 at.%. When the scan speed is further decreased to 9.2 cm s−1, the amorphous region narrows further such that only the best glass formers in the compositional space vitrify upon solidification. Here the range in Au content is only 48 to 56 at.%. Vitrified alloys from the 9.2 cm s−1 scan speed have R C values comparable to Au55Cu25Si20. For a scan speed of 6.9 cm s−1, all considered alloys crystallize.

Across multiple laser scan speeds, R C can be calculated from the slowest laser scan speed applied to vitrify the alloy. Once the slowest laser scan speed is determined, the numerical value of R C is obtained as the cooling rate at 0.8T L from the corresponding simulation (Fig. 2g). T L is extracted from the ternary phase diagram34. As the final result, R C is plotted as a function of composition (Figs 3e and 4a).

Comparison of composition-dependent GFA obtained from direct measurements with indirect GFA parameters (a) Contours of R C as a function of composition. (b) The measured R C is converted to d C based on casting into a mold with infinite thermal mass and thermal conductivity, i.e. only the thermal properties of the melt were considered39. Given R C in K s−1, the d C in meters is equal to \(\sqrt{\frac{0.01}{{R}_{C}}}\). (c) T rg = T g/T L where T g was estimated41 by first calculating the elastic moduli42,43 and calibrating with a known T g that was determined by calorimetry31 (calculation details discussed in caption of Supplementary Fig. 1), while T L was extracted from the ternary liquidus projection34. (d) Applying an efficient cluster-packing structural model for metallic glasses45, 100% efficiently packed lines for various <Z Si,tot, Z Cu,tot, Z Au,tot> structures were calculated for the composition region of interest. Indicated as a red line is the <10, 13, 15> structure, which is recommended by the authors of the model45 for the Au-Cu-Si system.

Discussion

The GFA for a large compositional space was directly determined using XRD and EDS mapping of alloy libraries heated with lasers at multiple scan speeds (Figs 3e and 4a). Upon sputtering, the composition range of Au between 39 to 66 at.%, Cu between 13 to 41 at.%, and Si 16 to 35 at.% forms the amorphous phase. The region of the highest GFA (R C ≤ 3.4 × 104 K s−1) spans from Au56Cu27Si17, along the approximately constant Cu line until Au48Cu28Si24. This region coincides, within margins of error, with Au55Cu25Si20, which is the alloy with the highest previously reported GFA as determined through cumbersome and numerous trial-and-error experiments31. The results are also consistent with the region of highest GFA determined by nanocalorimetry, which is the range between Au58Cu25Si17 and Au52Cu29Si19 21.

From our results, we can draw conclusions about the change of GFA with composition. When the Cu content is maintained between 25 to 30 at.%, R C is less sensitive to the Si concentration; R C increases gradually from 3.4 × 104 K s−1 to about 3 × 105 K s−1 when Si content increases from 17 to 29 at.% and then R C increases rapidly to over 1010 K s−1 when the Si concentration is 31 at.% or higher. On the low Si side, GFA drops abruptly once the Si content drops below 16 at.%. For the most extreme case, R C changes from 3.4 × 104 K s−1 to over 1010 K s−1 when the Si concentration decreases from 17 to 15 at.%. This implies that within a 2 at.% composition difference, R C can change by as much as six orders of magnitude. The degree of variations in GFA with composition are much larger than the variations recently reported for metal-metalloid glass formers35. However, it is conceivable that for the proposed method, particularly for this example system, some alloys crystallized rapidly even at ambient or sputtering temperatures (~293 to 323 K). Hence, an alloy that vitrified upon sputtering may have crystallized prior to characterization and would be identified as crystalline upon sputtering. Obviously, this situation is more likely to occur in alloys with glass transition temperatures (T g) in the vicinity of ambient temperatures such as for binary Au-Si glasses36. Evidence for such a scenario is the fact that Au75Si25 37 and Au81.4Si18.6 36 have both been reported to vitrify upon splat quenching (~106 K s−1 38), whereas sputtered (~1010 K s−1) Au-Si alloys are identified as crystalline. Hence, the composition-dependence of GFA, measured using the proposed method, should be carried out for alloy regions where T g is significantly larger than ambient temperature, arguably >340 K (Supplementary Fig. 1).

R C can be converted to the critical casting thickness (d C), the maximum thickness that a material can be made fully amorphous via quenching39; an often more practical measure (Fig. 4b). For Au-Cu-Si alloys with the highest GFA (R C of 3.4 × 104 K s−1), the d C is calculated to be 540 μm, consistent with reported values31. This confirms the proposed approach and indicates that there is no ternary bulk (d C ≥ 1 mm) MG (BMG) in the Au-Cu-Si system.

The availability of R C over such a large and unprecedented range of compositions (Figs 3e and 4a) makes it possible to test the validity of indicators of GFA that are widely used and provide insight into motives for glass formation. The reduced glass transition temperature (T rg = T g/T L), proposed by Turnbull, has been suggested to correlate directly with GFA40. However, like for most GFA indicators, T rg relies on parameters that are not known a priori and therefore have to be estimated (Fig. 4c). Here, T g was estimated41 as a function of composition by initially calculating the elastic moduli42,43 then correlating the elastic moduli values to T g which in turn was calibrated with a known T g determined by calorimetry31; T L was obtained from the liquidus projection of the ternary phase diagram34. In the composition range under consideration, the estimated T g values span from 326 to 376 K (Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with experimentally determined values44. Because the variation in T g is significantly less than the variation in T L, the composition dependence of T rg is primarily dictated by the change in T L.

Based on T rg, alloys with high GFA are expected to be near eutectic compositions. This is consistent with our reported findings (Figs 3e and 4a). The range of high GFA (R C ≤ 105 K s−1) corresponds to regions where T rg is above 0.4, i.e. between 14 and 27 at.% Si. Moving towards low Si concentrations, at ~15 at.%, the rapid drop in the measured GFA coincides with a steep decline in T rg. At the higher Si concentrations, the GFA drop is more gradual, despite a substantial decrease in T rg. Overall, the trends predicted by T rg agree broadly with the experimental GFA, although deviations as large as 10 at.% are possible. For example, the composition region of maximum T rg does not coincide with the compositions of maximum GFA determined experimentally.

A recently proposed model45, based on efficient cluster-packing, has also been tested against the experimentally determined composition dependence of R C (Fig. 4d). In short, the model identifies compositions and atomic size differences such that packing clusters are simultaneously efficiently packed about each constituent element. For ternary systems, the most efficiently packed structures form a line in the Gibbs triangle45.

The lines of 100% efficiently packed structures were calculated for compositions in the vicinity of the glass-forming range (Fig. 4d)45,46. The notation for indicating cluster packing structures is <Z Si,tot, Z Cu,tot, Z Au,tot>, where Z i,tot is the total number of atoms present in the first shell of a cluster centered about element i. The <10, 13, 15> structure has been suggested to represent Au-Cu-Si glass formers45. This line coincides with the line for the <10, 12, 15> structure and does indeed intersect with the center of the experimentally determined glass-forming range. Other structures, namely <10, 14, 16> and <10, 14, 17> coincide with the periphery of the experimentally determined glass-forming range. However, the line for the structure predicted by the efficient cluster-packing model, <10, 12, 14>, did not intersect with any glass formers. This comparison suggests that efficient cluster-packing model can assist in reducing the overall composition space, however this reduction is small.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness, practicality, and speed of the proposed technique to experimentally measure GFA over large composition ranges, a comparison with the total number of potential bulk glass forming alloys has to be made. It has been estimated that the number of potential BMG forming alloys is on the order of 106 alloys out of 1012 unique alloys with two to five constituent elements47. Assuming a fabrication rate of 1000 alloys per day with the proposed method, it would still require over 2,700,000 years to synthesize and characterize the entire alloy space. This comparison suggests that prior to the combinatorial method, a significant reduction in the composition space is required to tackle the complex phenomena of glass formation and to identify many of the yet to be discovered MG and BMG alloys. Here, using theoretical predictions based on parameters that are known a priori to identify glass forming systems and reduce the composition space of interest will be powerful48. Subsequently these suggested composition ranges would be characterized with our proposed combinatorial method to identify MG and BMG formers. In a final step, a small number of selected alloys, which are suggested by the combinatorial method, would be fabricated in bulk form and characterized by using highly precise and established bulk characterization methods. Thus, the proposed method can be considered the missing link for effective MG discovery.

Methods

Sample Fabrication, Laser Heating, and Characterization

The layered film structure is fabricated by confocal DC magnetron co-sputtering (AJA International ATC 2200) with elemental targets with purity exceeding 99.95%. The sputtering guns are arranged in a tetrahedral arrangement at a default angle of 29.8 degrees from the vertical. Prior to any sputtering step, a base pressure level of 10–6 Pa and a working pressure of 0.3 Pa of flowing ultra high purity (UHP) Ar is achieved. The substrates were 100 mm diameter, 500 μm thick, double-side polished, intrinsic Si wafers (UniversityWafer, Inc.). Firstly, 30 nm of W was sputtered at 70 W power. Then, 30 nm of Si3N4 was sputtered by reactive sputtering, using a Si sputtering gun at 70 W under flowing UHP Ar and additionally flowing 10 standard cm3 min−1 of UHP N2 gas. Finally, 1 μm of Au-Cu-Si alloy is co-sputtered with powers of 41 W, 37 W, and 175 W for Au, Cu, and Si, respectively. For a constant composition film, the substrate is rotated during the sputtering process. To fabricate alloy libraries with compositional gradients, the substrates are left stationary. Changing the sputtering power and tilt angles of each specific sputtering gun would alter the compositional spread of the libraries.

The as-sputtered alloy film is first characterized with automated XRD (Rigaku Smartlab) using Cu Kα radiation with a 2 mm beam mask and automated EDS (Oxford Instruments X-Max detector attached to a Zeiss Sigma VP Field Emission scanning electron microscope) to determine the structure and composition, respectively, as a function of position on the wafer. Next, the sample undergoes LSA using a 60 W CO2 laser (Universal Laser Systems VLS 6.60) at a set laser scan speed, incident from the heat sink (Si wafer) side. The laser scan lines are spaced 5 mm apart center-to-center to avoid heat affected zone interactions. Finally, the sample is then characterized with XRD and OM (Nikon ME600 with ThorLabs CCD camera).

Temperature profile simulations

Temperature profile simulations were done using the commercial package COMSOL Multiphysics® for time-dependent thermal finite element method simulations, informed by the experimental results. A 100 mm intrinsic Si wafer was modeled using temperature-dependent thermal conductivity, density, and specific heat capacity49. The wafer is assumed to be thermally isotropic. All surfaces are air-cooled with no forced convection (h = 5). Ambient temperature and the wafer edge were assumed to be 300 K. The laser was modeled as a Gaussian-shaped surface heat source, where the peak width and power was fitted with experimental measurements of the heat-affected zone size, which was measured using the OM images with ImageJ50 software. The thin photo-thermal and alloy layers, having high thermal diffusivities and low thermal masses, are assumed to be isothermal to the top surface of the Si wafer. The temperature profiles for different scan speeds (Fig. 2g) were recorded from one fixed point, located 1.27 cm from the origin of laser incidence and along the path of the laser scan to allow time to reach a stable temperature.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

12 December 2018

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Nishiyama, N. & Inoue, A. Supercooling investigation and critical cooling rate for glass formation in Pd–Cu–Ni–P alloy. Acta Materialia 47, 1487–1495 (1999).

Mukherjee, S., Schroers, J., Johnson, W. L. & Rhim, W. K. Influence of Kinetic and Thermodynamic Factors on the Glass-Forming Ability of Zirconium-Based Bulk Amorphous Alloys. Physical Review Letters 94, 245501 (2005).

Zhong, L., Wang, J., Sheng, H., Zhang, Z. & Mao, S. X. Formation of monatomic metallic glasses through ultrafast liquid quenching. Nature 512, 177–180 (2014).

Pogatscher, S., Leutenegger, D., Hagmann, A., Uggowitzer, P. J. & Löffler, J. F. Characterization of bulk metallic glasses via fast differential scanning calorimetry. Thermochimica Acta 590, 84–90 (2014).

Pogatscher, S., Uggowitzer, P. J. & Löffler, J. F. In-situ probing of metallic glass formation and crystallization upon heating and cooling via fast differential scanning calorimetry. Applied Physics Letters 104, 251908 (2014).

Bai, F. X., Yao, J. H., Wang, Y. X., Pan, J. & Li, Y. Crystallization kinetics of an Au-based metallic glass upon ultrafast heating and cooling. Scripta Materialia 132, 58–62 (2017).

Macarron, R. et al. Impact of high-throughput screening in biomedical research. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 10, 188–195 (2011).

Schnabel, V. et al. Revealing the relationships between chemistry, topology and stiffness of ultrastrong Co-based metallic glass thin films: A combinatorial approach. Acta Materialia 107, 213–219 (2016).

Guo, Q. et al. Compositional dependence of Young’s moduli for amorphous Cu–Zr films measured using combinatorial deposition on microscale cantilever arrays. Scripta Materialia 64, 41–44 (2011).

Li, Y., Guo, Q., Kalb, J. A. & Thompson, C. V. Matching Glass-Forming Ability with the Density of the Amorphous Phase. Science 322, 1816–1819 (2008).

Deng, Y. P. et al. A combinatorial thin film sputtering approach for synthesizing and characterizing ternary ZrCuAl metallic glasses. Intermetallics 15, 1208–1216 (2007).

Ding, S., Gregoire, J., Vlassak, J. J. & Schroers, J. Solidification of Au-Cu-Si alloys investigated by a combinatorial approach. Journal of Applied Physics 111, 114901–114906 (2012).

McCluskey, P. J. & Vlassak, J. J. Glass transition and crystallization of amorphous Ni–Ti–Zr thin films by combinatorial nano-calorimetry. Scripta Materialia 64, 264–267 (2011).

McCluskey, P. J. & Vlassak, J. J. Combinatorial nanocalorimetry. Journal of Materials Research 25, 2086–2100 (2010).

Ryusuke, Y., Seiichi, H., Junpei, S. & Akira, S. Combinatorial Search for Low Resistivity Pd–Cu–Si Thin Film Metallic Glass Compositions. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 45, 5911 (2006).

Liu, Y. et al. Combinatorial development of antibacterial Zr-Cu-Al-Ag thin film metallic glasses. Scientific Reports 6, 26950 (2016).

Doubek, G. et al. Guided Evolution of Bulk Metallic Glass Nanostructures: A Platform for Designing 3D Electrocatalytic Surfaces. Advanced Materials (2015).

Ding, S. et al. Combinatorial development of bulk metallic glasses. Nature Materials 13, 494–500 (2014).

Sakurai, J., Hata, S., Yamauchi, R. & Shimokohbe, A. Combinatorial arc plasma deposition search for Ru-based thin film metallic glass. Applied Surface Science 254, 720–724 (2007).

Li, Y. et al. Combinatorial Strategies for Synthesis and Characterization of Alloy Microstructures over Large Compositional Ranges. ACS Combinatorial Science 18, 630–637 (2016).

Gregoire, J. M. et al. Combining combinatorial nanocalorimetry and X-ray diffraction techniques to study the effects of composition and quench rate on Au–Cu–Si metallic glasses. Scripta Materialia 66, 178–181 (2012).

Tsai, P. & Flores, K. M. A combinatorial strategy for metallic glass design via laser deposition. Intermetallics 55, 162–166 (2014).

Tsai, P. & Flores, K. M. A Laser Deposition Strategy for the Efficient Identification of Glass-Forming Alloys. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 46, 3876–3882 (2015).

Tsai, P. & Flores, K. M. High-throughput discovery and characterization of multicomponent bulk metallic glass alloys. Acta Materialia 120, 426–434 (2016).

Harris, T. R. Optical properties of Si, Ge, GaAs, GaSb, InAs, and InP at elevated temperatures. Air Force Institute of Technology (2010).

Green, M. A. & Keevers, M. J. Optical properties of intrinsic silicon at 300 K. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 3, 189–192 (1995).

Zhou, X., Zhao, A., Yuan, M. & Yu, X. Study on infrared absorption of tungsten nanofilms. SPIE Proceedings 8202, 820217 (2011).

Lang, W., Kühl, K. & Sandmaier, H. Absorbing layers for thermal infrared detectors. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 34, 243–248 (1992).

Wang, X., Bellouard, Y. & Vlassak, J. J. Laser annealing of amorphous NiTi shape memory alloy thin films to locally induce shape memory properties. Acta Materialia 53, 4955–4961 (2005).

Jung, B. et al. Sub-millisecond post exposure bake of chemically amplified resists by CO2 laser heat treatment. SPIE Proceedings 7639, 76390L (2010).

Singer, J. P. et al. Alignment and reordering of a block copolymer by solvent-enhanced thermal laser direct write. Polymer 55, 1875–1882 (2014).

Singer, J. P., Kooi, S. E. & Thomas, E. L. Focused laser spike (FLaSk) annealing of photoactivated chemically amplified resists for rapid hierarchical patterning. Nanoscale 3, 2730–2738 (2011).

Cretu, C. & van der Lingen, E. Coloured gold alloys. Gold Bulletin 32, 115–126 (1999).

Liu, J. et al. Combinatorial exploration of color in gold-based alloys. Gold Bulletin 48, 111–118 (2015).

Schroers, J., Lohwongwatana, B., Johnson, W. L. & Peker, A. Gold based bulk metallic glass. Applied Physics Letters 87, 061912 (2005).

Ordal, M. A., Bell, R. J., Alexander, R. W., Newquist, L. A. & Querry, M. R. Optical properties of Al, Fe, Ti, Ta, W, and Mo at submillimeter wavelengths. Applied Optics 27, 1203–1209 (1988).

Chen, H. S. & Turnbull, D. Thermal Properties of Gold‐Silicon Binary Alloy near the Eutectic Composition. Journal of Applied Physics 38, 3646–3650 (1967).

Klement, W., Willens, R. H. & Duwez, P. O. L. Non-crystalline Structure in Solidified Gold-Silicon Alloys. Nature 187, 869–870 (1960).

Villars, P. & Okamoto, H. Au-Cu-Si Liquidus Projection of Ternary Phase Diagram: Datasheet from “PAULING FILE Multinaries Edition – 2012” in SpringerMaterials (http://materials.springer.com/isp/phase-diagram/docs/c_1500096). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg & Material Phases Data System (MPDS), Switzerland & National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS), Japan.

Lin, X. H. & Johnson, W. L. Formation of Ti–Zr–Cu–Ni bulk metallic glasses. Journal of Applied Physics 78, 6514–6519 (1995).

Wang, W. H. Elastic moduli and behaviors of metallic glasses. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 351, 1481–1485 (2005).

Wang, W. H. Correlations between elastic moduli and properties in bulk metallic glasses. Journal of Applied Physics 99, 093506 (2006).

Callister, W. D., Rethwisch, D. G. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction, Ninth edn. Wiley (2014).

Laws, K. J., Miracle, D. B. & Ferry, M. A predictive structural model for bulk metallic glasses. Nature Communications 6, 8123 (2015).

Na, J. H. et al. Compositional landscape for glass formation in metal alloys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 9031–9036 (2014).

Ruhl, R. C. Cooling rates in splat cooling. Materials Science and Engineering 1, 313–320 (1967).

Turnbull, D. Under what conditions can a glass be formed? Contemporary Physics 10, 473–488 (1969).

Wang, C., Liao, Y.-C., Chu, J. P. & Hsueh, C.-H. Viscous flow and viscosity measurement of low-temperature imprintable AuCuSi thin film metallic glasses investigated by nanoindentation creep. Materials & Design 123, 112–119 (2017).

Miracle, D. B., Sanders, W. S. & Senkov, O. N. The influence of efficient atomic packing on the constitution of metallic glasses. Philosophical Magazine 83, 2409–2428 (2003).

Li, Y., Zhao, S., Liu, Y., Gong, P. & Schroers, J. How many bulk metallic glasses are there? Personal Communication (2017).

Miracle, D., Majumdar, B., Wertz, K. & Gorsse, S. New strategies and tests to accelerate discovery and development of multi-principal element structural alloys. Scripta Materialia 127, 195–200 (2017).

Shanks, H. R., Maycock, P. D., Sidles, P. H. & Danielson, G. C. Thermal Conductivity of Silicon from 300 to 1400 °K. Physical Review 130, 1743–1748 (1963).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by National Science Foundation (NSF) DMREF/GOALI 1436268. The authors are grateful for characterization facilities provided by NSF MRSEC DMR 1119826 (CRISP) and the Yale Institute for Nanoscience and Quantum Engineering (YINQE). The authors would like to thank Glenn Weston-Murphy for his help with the laser equipment. The authors would also like to thank Sungwoo Sohn, Frederick J. Walker, Chinedum O. Osuji, Michael Loewenberg, and Corey S. O’Hern for fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.B., J.P.S., and J.S. designed the study. P.B., J.L., and S.A.K. fabricated the samples. P.B. and T.M. performed the laser heating experiments and OM imaging. P.B., J.L., and Y.L. performed the XRD measurements. B.E.S. and C.C.B. performed the EDS measurements. J.P.S. performed the temperature profile simulations. J.P.S., J.J.V., and J.S. advised the research. All authors contributed to the data analysis, discussion, and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bordeenithikasem, P., Liu, J., Kube, S.A. et al. Determination of critical cooling rates in metallic glass forming alloy libraries through laser spike annealing. Sci Rep 7, 7155 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07719-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07719-2

This article is cited by

-

Elemental partitioning-mediated crystalline-to-amorphous phase transformation under quasi-static deformation

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Substantially enhanced homogeneous plastic flow in hierarchically nanodomained amorphous alloys

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Rational design and glass-forming ability prediction of bulk metallic glasses via interpretable machine learning

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Compositional dependence of the fragility in metallic glass forming liquids

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of an amorphous solid

Nature (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.