Abstract

An efficient and recyclable palladium (II) catalyst supported on a double-structured amphiphilic polymer composite was reported previously containing a polymer hydrogel within macroporous polystyrene (PS) microspheres. However, some critical questions have been unaddressed. First, the catalyst accelerated the heterogeneous ligand-free batch Suzuki-Miyaura reaction in a H2O/EtOH mixture solution at room temperature in the presence of air, which could be ascribed to the “on-water” effect taking place at the interface of the aqueous–organic and basic-aqueous phases created by sodium carbonate in H2O/EtOH. To this acceleration, the double-structured amphiphilic polymer composite can also contribute by providing hydrogels inside the macroporous PS that served as a microreactor. This microreactor allowed the reactions to quickly proceed across the two immiscible (i.e. aqueous-organic and basic-aqueous) phases. Moreover, hydrogels containing hydroxyl groups can also serve as phase-transfer catalysts (PTC) to promote the Suzuki reaction. Second, the deactivated catalyst recovered its initial catalytic activity after overnight air exposure. This observation indicates the importance of oxygen in the activation/deactivation of Pd metals, as determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements which revealed different Pd oxidation states with various morphologies before and after Suzuki reactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of organic transformations at mild conditions has dramatically improved the environment, economy, and safety of consumers within the last two decades. Transition metal-catalysed C–C cross coupling reactions such as the Suzuki–Miyaura have been pivotal in the development of a variety of important pharmaceutical synthesis routes1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. These reactions typically require high amounts of catalyst (1–10 mol%) and long reaction times (from several hours to a few days)9,10,11, and thereby require safer and greener reaction conditions being both efficient and cost-effective12,13,14,15,16,17. However, only a few methods for carrying out the reaction in an aqueous medium at room temperature have been developed. To circumvent this phase-transfer limitation in the aqueous medium associated with the water-insoluble nature of the substrates, methods based on the utilisation of surfactants, inverse phase-transfer catalysts, supramolecular reactors and water-soluble ligands have been largely used to enhance the reaction rates. However, this area still requires to be further explored.

From an industrial viewpoint, the deposition of Pd nanoparticles on supports is preferred since the obtained catalysts are easier to handle, recover, and re-use within the selected process. Apart from the aforementioned advantages, we believe that these supported Pd catalysts bearing various functional groups can further improve the coupling reaction. For instance, the use of polymers as catalyst supports in continuous flow reactions allows recovering the leached Pd in a similar way as to a chromatography resin. Polymers such as polyethylene oxide (PEO) can be used as phase-transfer catalysts (PTC) to accelerate aqueous-phase Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions18, 19.

The present study is a follow-up of our previously published communication20 containing experimentally based detailed discussions, with some complicated questions left unanswered. In this study, heterogeneous refers to the dissolution of some of the reactants in the reaction mixture to form a suspension. On the other hand, homogeneous refers to the complete dissolution of all reactants in the reaction mixture to form a homogeneous solution. The present study will first examine the accelerated completion of the heterogeneous Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction in a H2O/EtOH solution in the presence of our polymer composite-supported Pd catalysts (reaction conditions: 0.25 mmol 4-bromobenzaldehyde, 0.275 mmol phenyl boronic acid, 1 mL H2O/EtOH (v/v 1:1), 0.01–1 mmol% Pd, room temperature in the presence of air and 5–10 min for reaction completion). In contrast, the homogenous solutions with all reactants dissolved (under the same reaction conditions, except for 10 mL H2O/EtOH (v/v 1:1), 0.06 mol% Pd) required more than 6–8 h to complete the coupling reaction20. Additionally, this study will try to answer the following questions: (i) Why is not possible to reuse the catalyst right after a Suzuki coupling reaction? and (ii) Could the catalyst recover its initial catalytic activity after being kept under air overnight or longer? To provide answer to these questions, we conducted Suzuki coupling reactions with bromoarenes bearing electron withdrawing and donating groups under batch and continuous-flow reaction conditions. Several reaction parameters (e.g. reactant concentrations, water to ethanol ratio and Pd loading) were investigated to tentatively disclose the underlying mechanism of the accelerated Suzuki reactions while also elucidating the role of the polymer support in this process.

Results and Discussion

Kinetics of aqueous heterogeneous batch reactions

Heterogeneous aqueous reactions are advantageous in that they allow high reactant concentrations and simple product isolation while also being safer and less costly as compared to those carry out in organic solvents. As previously reported, our polymer composite-supported Pd catalyst could be used for ligand-free Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions at room temperature. First, the catalytic efficiencies of PCS1 and PCS2 were compared with those of two commercial polymer composite-supported Pd catalysts (Pd/C and PdEnCatTM40) under heterogeneous reaction conditions. The Pd loading used was 1 mol% for the two commercial catalysts. At this Pd loading, PCS1 and PCS2 showed extremely fast coupling reaction rates and therefore their results were not included herein. In this sense, the Suzuki coupling reaction of 4-bromobenzaldehyde with phenyl boronic acid is typically completed in less than 5 min with PCS1 at a Pd loading greater than 0.01% (1 mol% for PCS2). As shown in Fig. 1, PCS1 is the most efficient supported Pd catalyst able to complete the reaction in 30 min and 2 h at only 0.006 and 0.001 mol% Pd, respectively. In contrast, commercial Pd/C at 1 mol% Pd showed a conversion of ca. 95% after 2 h, while PdEnCatTM40 with the same Pd loading reached 78% conversion after 4–5 h of reaction. Additionally, an induction period was observed for the two commercial catalysts (ca. 1 and 3 h for Pd/C and PdEnCatTM40, respectively), thereby revealing some adverse effects of the reactant mixture over the supported Pd active sites. In contrast, no induction period was observed for PCS1 and PCS2. Instead, the conversion of the reactant proportionally increased with the reaction time during the first half of the catalytic process at various Pd loadings. Additionally, we compared the research data disclosed recently on various Pd catalysts for aqueous Suzuki reactions (see Supplementary Table S1), and concluded that our polymer composite supported catalyst predominantly showed superior catalytic efficiencies while being more environmentally friendly.

Kinetics of the heterogeneous coupling of 4-bromobenzaldehyde with phenyl boronic acid catalysed by Pd catalyst PCS1 at Pd loadings of 0.006 mol% (red empty circle) and 0.001% mol (black empty square), by PCS2 at Pd loadings of 0.1 mol% (red solid circle) and 0.01 mol% (black solid square), by Pd/C (1 mol%, blue solid triangle), and by PdEnCatTM40 (1 mol%, green solid star) under concentrated batch condition. (4-bromobenzaldehyde 0.25 M, phenyl boronic acid 0.275 M, H2O/EtOH (v/v 1:1, total volume 1 mL) at room temperature without argon protection.

Kinetics of Aqueous Homogenous Batch Reactions

With the aim to confirm whether this ultrafast nature of the Suzuki reaction could be achieved under homogenous/dilute batch conditions, we investigated the conversion of bromoarenes with both electron-withdrawing and electron-donating functional groups as a function of time. As shown in Fig. 2, PCS1 (Pd loading of only 0.006 mol%) under heterogeneous conditions showed coupling rates in the following order: 1a > 1b > 1c. Under homogenous conditions (i.e. 10-fold diluted reactant concentration and Pd loading increased 10-fold to 0.06 mol%) the Pd catalyst 1a and 1b showed conversion higher than 98% within 8 h in the presence of electron-withdrawing groups, and this conversion decreased to ca. 70% in the case of 1c (bearing an electron-donating functional group) and remained constant with time. These results summarizing the effect of various functional groups are in agreement with those previously published in the literature21. However, the dilution employed might also contribute to decrease the reaction rate. This might indicate that the reaction did not take place in the aqueous phase since the reaction rates “in-water” are typically faster under dilute conditions22. Thus, we propose that the ultra-fast Suzuki coupling observed herein might occur at the interface of the solvent mixture (i.e. “on-water” reactions)23.

Conversion of aryl bromides (0.25 mmol) at different intervals in the batch Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of phenyl boronic acid (0.275 mmol) in H2O/EtOH (1:1 v/v) under heterogeneous (1 mL) and homogeneous conditions (10 mL) at room temperature. Concentrations of aryl bromides and phenyl boronic acid are 0.25 M and 0.275 M, 0.025 M and 0.0275 M, respectively. The Pd loadings with respect to aryl bromides are 0.006 mol% and 0.06 mol%, for concentrated and dilute reactions, respectively.

On-water effect on the acceleration of the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction under heterogeneous batch conditionsn

The causes behind the rate acceleration in homogenous water-based reactions have been extensively investigated24. In the case of heterogeneous aqueous reactions, several factors such as the concentration of the reactants, the water/organic solvents ratio, the phase splitting of the reaction media, and the stirring speed might account for the observed on-water acceleration effect. In heterogeneous Suzuki coupling reactions, a microscopic phase separation is present between two phases: aqueous-organic phase with lower pH and aqueous basic phase with higher pH25. Phenyl boronic acid is ionized in the aqueous basic phase. Thus, unlike the positive ions that are repelled from the interfaces, phenyl boronic acid is present mostly in excess at the interfaces of the two phases26. On the other hand, organic acryl bromide molecules should be present in the aqueous–organic phase such that the coupling mainly occurs at the organic–water interface rather than in the organic phase. As shown in Fig. 3, 0.25 M solutions of 1a (electron-withdrawing group) and 1c (electron-donating group) were hardly converted when in a total volume of reaction of 1 mL of pure ethanol or water. However, the coupling rates increased with the ethanol to water (v/v) or water to ethanol ratios up to 0.5.Notably, two parameters might influence the reaction rates provided the Suzuki coupling reactions take place at the water–ethanol interface: a) the solubility of the reactants in ethanol (aryl bromides) and water (phenyl boronic acids and sodium carbonate); and b) the interface area between the aqueous–organic (acryl bromide/ethanol) and the basic aqueous (containing phenyl boronic acid and sodium carbonate) phases. The former is determined by the relative amounts and ratio of the solvent mixture, whereas the latter is influenced by solvent mixture ratio and the stirring intensity. In our case, although ethanol is miscible in water, the addition of sodium carbonate induced phase splitting, as commonly observed for water-miscible solvents such as tetrahydrofuran (THF), dioxane and methanol typically employed for the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction. The extended UNIQUAC model27 previously described in detail this liquid–liquid split of the aqueous ethanol solution containing Na2CO3. As for the on-water reactions, the difference between the homogenous and heterogeneous reactions can be attributed to the reaction occurring at the extensive aryl bromide/ethanol oil droplet interfaces, these reactions being significantly faster than those in the bulk. For a given total amount of reactants, the rate of the surface reaction is inversely proportional to the size of the droplets since small droplets have larger total surface area-to-volume ratios28. Obviously, in dilute homogenous reactions, the surface area of the aryl bromide/ethanol-water mixture is very low or nearly zero, thereby allowing the Suzuki coupling reaction to proceed in the homogenous bulk solution without the occurrence of the on-water acceleration process and explaining the low conversion of bromoarenes in pure ethanol and water (Fig. 3). The interface area may reach a maximum at water/ethanol ratios close to 1, thereby allowing the on-water effect. This phenomenon was also described by Sharpless et al. for other organic transformations. These authors observed significantly lower reaction times (by a factor of 300) for a heterogeneous mixture of reactants on water as compared to a homogenous solution of reactants in water29. From the viewpoint of the molecular reactions, the -OH groups of water play a vital role in the on-water catalysis. At the emulsion/heterogeneous interface, some OH groups can migrate into the organic phase being readily available to catalyse the reactions. In the homogenous solution, the existing H-bond network from the water molecules surrounds the reactant before releasing the OH groups to catalyse the reactions28, 30. This process requires both time and energy, thereby decreasing the rate of the homogeneous reactions versus the heterogeneous reactions.

Investigation of the influence of the ratio H2O/EtOH on the conversion of aryl bromides (0.25 M) in batch Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, with phenyl boronic acid (0.275 M) in H2O/EtOH under concentrated condition in 10 min at room temperature in air with PCS1 at 0.01 mol% Pd loading with respect to the aryl bromides.

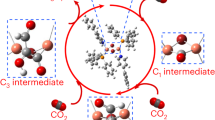

Mechanism and role of the polymer support in the on-water Suzuki–Miyaura reactions

To characterize the role of the support in this unique on-water acceleration reaction, we compared its catalytic activity with those of commercial supported catalysts (i.e. Pd/C and PdEnCatTM40), and the results are summarized. (see Supplementary Table S2). Pd/C and PdEnCatTM40 also catalysed the Suzuki coupling reaction at room temperature, and moderate yields of the products were obtained within one to several hours. According to the merchant’s website, PdEnCatTM40 can convert 94% of 4-bromoanisole to the desired product within 8–12 h in a toluene/water/ethanol (4/2/1) solvent mixture at an elevated temperature of 80 °C 31, which indicates the importance of a proper solvent selection. In terms of the role of the different supports, activated carbon in Pd/C might only serve as a support since the inner walls of the reaction flask were observed to have a black film of Pd metal after the Suzuki coupling reaction. In contrast, no precipitation of black metal was observed during the entire coupling process for both PdEnCatTM40 and polymer composite-supported PCS1 and PCS2 catalysts. PdEnCatTM40 was supported on a macroporous polyurea matrix, whereas the supports of PCS1 and PCS2 consisted of soft hydrophilic polymer gels with hydroxyl or amide functionalities. Therefore, these polymeric matrices functioned as a support while also interacting with Pd and preventing it from agglomeration or deactivation processes. However, PdEnCatTM40 showed an induction time and did not accelerate the heterogeneous Suzuki reaction (Fig. 1), thereby implying that hydrophobic polyurea is less effective than the hydrophilic hydrogels of PCS1 and PCS2. We also propose that the use of hydrophilic PHPA gels as PTCs can contribute to the on-water acceleration of the Suzuki coupling reaction.

Polymers have been widely used as PTC. For instance, PEG has been often utilised as a PTC in a variety of processes (e.g. Suzuki coupling reactions18), given the ability of the poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) chains to form complexes with the metal ions19 while also being capable of transferring active ArB(OH)3− species from the aqueous to the organic phase18. The mechanism is that the oxygen in the PEO chains accepts H+ from phenylboronic acid to maintain the electron neutrality of the surrounding environment. Likewise, ArB(OH)3− species can also passively accumulate around the polymer chains.

Likewise, in the case of PCS1, numerous -OH groups from the PHPA hydrogel also attract H+, thereby allowing the migration of ArB(OH)3− species from the basic aqueous to the aqueous–organic phase and accelerating the Suzuki coupling reactions. The chemical nature of the supports in PCS2 and PdEnCatTM40 (i.e. amide groups) did not increase the coupling reaction rate to the same extent of PCS1. Furthermore, the amphiphilic nature of the polymer composite supports as well as their three-dimensional network resulted in swollen hydrogels that facilitated the diffusion of different reactants and product molecules in and out of the macropores. These polymer chains with a hydrated conformation (in case of hydrophilic polymers) were previously observed to present maximum catalytic activity32. A possible mechanism for the heterogeneous batch Suzuki coupling reaction over PCS1 is depicted in Fig. 4 that considers the above discussions and theories.

Kinetics of aqueous homogenous continuous flow reactions

Supported Pd catalysts can be used for Suzuki coupling reactions at room temperature without the addition of ligands and inert gas protection. Thus, these catalysts are more suitable for large scale continuous flow reactions at the industrial scale. However, the longevity and stability of these catalysts require further testing. The apparatus employed for the flow reaction is depicted (see Supplementary Fig. S3). The PCS1-catalysed coupling reaction between 4-bromobenzaldehyde and several phenyl boronic acids was monitored with the conversion of 4-bromobenzaldehyde as a function of time (Fig. 5). Nearly 99% of the reactant was converted within 3–40 min, and this conversion was higher than 80% within 100 min (residence time: ca. 3 min; Pd loading: 0.033 mmol, concentration: 0.0125 M), thereby suggesting the high efficiency of the supported catalyst. Conversion moderately decreased with time (>50% for both 0.0125 and 0.025 M 4-bromobenzaldehyde solutions within 230 min). As expected, further increasing of the concentration to 0.05 and 0.1 M led to more severe and progressive deactivation of the supported Pd catalyst. Thus, higher concentrations of reactants have opposite effects on the heterogeneous batch and homogenous continuous flow reactions, and obviously no “on water” effect was observed in the continuous flow reactions. This can also be ascribed to the homogeneity of the reaction mixture as explained for homogeneous batch reaction.

Identification of the active Pd species in Suzuki coupling reactions

The true nature of the active Pd species in heterogeneous Suzuki coupling reactions was also investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements. The asymmetric shapes of the Pd 3d bands in all the XPS spectra (see Supplementary Fig. S4) suggest the presence of several Pd species in the catalytic system. Two pairs of peaks with different intensities were observed after the deconvolution of the curves. The binding energies (BE) of the Pd 3d bands of PCS1 before and after the Suzuki and Heck reactions under different reaction conditions are summarized in Table 1. In the case of the as-prepared PCS1, the presence of double peaks at ca. 337.2 (Pd3d 5/2) and 342.5 eV (Pd3d 3/2) confirmed the successful immobilization of Pd(II) on the polymer composite support33. After the Suzuki and Heck reactions, large amounts of Pd(II) (>60%) were in situ reduced to Pd(0), and this was accompanied with a colour change in the catalyst (from light yellow to grey). Although only two Pd species were studied herein, the presence of “electron deficient” Pd species (Pdδ+, 0 < δ < 1) cannot be ruled out34. The strong interaction between the metal and oxygen atoms on the supports resulted in XPS spectra revealing higher metal oxidation states35. As stated in our previously published report, PCS1 and PCS2 were unsuccessfully reused after successive Suzuki coupling reactions. However, we further discovered that keeping the used catalysts under air overnight or longer was beneficial to recover the initial activity of the catalysts for Suzuki coupling reaction cycles. An XPS analysis of the Pd species revealed that a large fraction of Pd(0) was oxidized to Pd(II)/Pdδ+ under air as previously reported by two independent research findings36, 37. For example, the Pd(0) species sequestered within G4-OH were gradually oxidized to Pd(II) with time under laboratory atmosphere37. Remarkably, no isolated PdO species were observed, thus it was hypothesized that the Pd ions were coordinated to/with the dendrimer internal structure. Furthermore, this oxidative reaction was reversible, as the oxidized Pd nanoparticles were found to be reduced to Pd(0) by either hydrogen gas or during the Suzuki coupling reaction38. In our study, the high amounts of Pd(0) produced after the first Suzuki reaction were catalytically inactive. In contrast, used PCS1 containing a high fraction of Pd(II)/Pdδ+ species upon air oxidation was catalytically active. Thus, Pd(II)/Pdδ+ (Pd in higher oxidation states) are proposed to favour the Suzuki coupling reactions, whereas both Pd(0) and Pd(II) are the catalytically active species for the Heck reaction. Even the Pd(0) species were formed after both the reactions, they may present different physical properties and therefore different catalytic activities, which will be discussed in the following part.

Crystalline structure of the supported Pd catalyst

PCS1 was analysed before and after the Suzuki and Heck reactions by X-ray diffraction (XRD). It is well known that the crystalline structure of the metal is important to its catalytic activity. For instance, the catalytic selectivity of Pt in the benzene hydrogenation reaction was found to be strongly affected by the shape of the nanoparticles39. As shown in Fig. 6A, broad diffraction peaks centred at ca. 2θ = 41.2° can be ascribed to amorphous Pd(II) on as prepared PCS1, which is in agreement with the XPS results. After 1st Suzuki coupling reaction, PCS1 showed only one broad peak at ca. 39.5°, which is a characteristic of amorphous metallic palladium Pd(0) (Fig. 6B). After air oxidation, used PCS1 showed a broad peak (Fig. 6C) similar to that for Pd(II) (Fig. 6A) with reduce intensity. In contrast, the diffractogram of the catalyst after 1st Heck reaction showed one sharp peak at ca. 40.2° and two weak peaks at 46.7 and 68.2°, which correspond to the (111), (200), and (220) crystallographic planes of the face-centred cubic crystalline (fcc) phase of Pd metal (Pd(0))40. The (111) peak was significantly more intense than that of the (200) plane, indicating randomly oriented three-dimensional assembly of the Pd crystals41. The intensities of the three peaks of crystalline Pd(0) decreased after the 10th Heck reaction, thereby suggesting partial loss of the ordered structure during the cycle reaction. Thus, the different morphology of the Pd(0) species in PCS1 after the 1st Suzuki and 1st Heck reaction also contributed to its different recyclability in the both reactions.

XRD patterns of polymer composite supported Pd catalyst PCS1: (A) as-prepared polymer composite supported Pd (II) catalyst. (B) After 1st heterogeneous batch Suzuki reaction of 4-bromobenzaldehyde with phenyl boronic acid; (C) kept in air after 1st heterogeneous batch Suzuki reaction; (D) after 1st Heck reaction; (E) after 10th Heck reaction of iodobenzene with butyl acrylate.

Change in the surface of the polymer composite

In the design of our polymer composite support, the macroporous hard polymer skeleton PS provided a structural protection for the soft gels PHPA and PDMAA. These gels grow and interpenetrate within the pores of the skeleton, thus leading to a three-dimensional network. The different swellabilities of the gels in aqueous and organic solvents and the morphological change of the support during the organic transformations may have also influenced their interactions with the supported metal catalysts and consequently their catalytic activities. Thus, the surface composition of the support was examined by XPS. The carbon to oxygen (C/O) atomic ratios were calculated as follows: NC/NO = (IC/SC)/(IO/SO)42. In the case of PCS1, the C/O atomic ratio for the support remained nearly unchanged after the first Suzuki coupling reaction (1.98 versus ca. 2.03 for pure PHA), thereby implying that the surface of the support surface was mainly covered with PHA hydrogels in the aqueous solution. This value increased to ca. 2.3 after the first and tenth Heck reactions in n-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), which suggests the hydrophilic moieties in the organic solvent such as hydroxyl groups removed from the support surface by retracting inside the deeper PS macropores. To confirm this, pore properties of PCS1 before and after the both coupling reactions were also measured with BET and results summarized (see Supplementary Table S5). Obviously, after the Heck reaction, the pore volume and diameter were reduced substantially in NMP, whereas the pore property of the support was slightly changed in H2O/ethanol for the Suzuki reaction. On the other hand, the peak intensity ratio of Pd 3d to C1s was 0.195 after the first Suzuki coupling reaction (versus 0.084 for the as-prepared PCS1 and 0.023 after the first Heck reaction). These results imply the presence of a more significant number of Pd ions on the support surface or, alternatively, the formation of larger Pd nanoparticles during the Suzuki reaction as compared with the Heck reaction process.

Conclusions

We herein addressed the questions related to the efficiency and recyclability of Pd(II) catalyst supported on a double-structured amphiphilic polymer composite. The observed rate increase of the heterogeneous ligand-free Suzuki-Miyaura reaction in water/ethanol at room temperature in the presence of air has been scarcely investigated in the literature. We ascribed this difference between the heterogeneous and homogenous reactions to the on-water effect taking place on the interfaces of the aqueous-organic (at low pH) and the basic aqueous (at high pH) phases which was discussed in detail. The hydrogels contained in the polymer composite, along with its hydroxyl groups, can also serve as PCT in organic transformations promoting the Suzuki reaction. Additionally, the deactivated catalyst in the Suzuki reactions can recover its initial catalytic activities after an overnight air treatment. XPS and XRD studies revealed the presence of different Pd oxidative states and various Pd morphologies before and after the Suzuki and Heck reactions, with oxygen likely playing a key role in the activation and deactivation of the Pd metal. In summary, this double-structured polymer composite-supported Pd material is an efficient and cost-effective catalyst for performing green Suzuki reactions.

Experimental

Materials

Pd(OAc)2 (99%, Sigma-Aldrich), phenylboronic acid (97%, Fluka), 4-bromobenzaldehyde (99%, Alfa Aesar), 4-bromoanisole (99%, Alfa Aesar), were used as received. The synthesis of polymer composite supported Pd catalyst was described in literature11. Pd(OAc)2 catalyst was supported on polymer composites containing polystyrene (PS) macroporous spheres and polymer hydrogels, with poly(2-hydroxypropyl acrylate) being denoted as PCS1 (Pd loading 0.065 mmol/g), and poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) as PCS2 (Pd loading 0.075 mmol/g). Pd/C (palladium on activated charcoal, 10% Pd basis, 0.939 mmol/g) and PdEncatTM40 (0.4 mmol/g) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

1 HNMR measurement was conducted on an Avance III spectrometer (400 MHz, Bruker, Germany). Briefly, the final experimental mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (DCM) and the organic layer was collected and vacuum dried. Then the product was dissolved in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) for 1HNMR measurements using TMS as internal standard, and conversions were determined on the bases of aryl halides.

X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted on a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. The samples were mounted in a low background sample holder and scanned at a rate of 0.02 step−1 over the 80° ≥ 2 ≥ 30° range with a scan time of 5 s step−1. The diffractograms were compared with the references for identification purpose.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed on an ESCALAB 250 spectrometer, using Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV, pass energy 20.0 eV). The base pressure of the instrument is <2.0 × 10−8 mbar. A Shirley background was applied to subtract the inelastic background of core-level peaks. The model peak to describe XPS core-level lines for curve fitting was a product of Gaussian and Lorentzian functions. Charge effects were corrected by using the C 1s peak at 285.0 eV. The instrument was also calibrated by using Au wire. XPS spectra were recorded at 90°.

Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) test was performed on a surface area & pore size analyser (Beckman SA3100, USA) with N2 adsorption at 77 K.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP-AES) test: The Pd content of the catalysts was measured on an IRIS intrepid spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). For typical sample preparation, ca. 20 mg of supported Pd catalyst was reflux in 2 mL concentrated acids (HCl:HNO3 = 3:1 v/v). After the solid was completely decomposed, the clear solution was diluted to 10 mL in volumetric flask with DI water. Characteristic wavelengths of 229.651, 340.458 and 360.955 nm were monitored and linear calibration curves were generated.

Batch and Continuous-flow Suzuki Cross-coupling Reactions

For batch-type reactions, a two-neck round flask was loaded with phenyl boronic acid (0.275 mmol), acryl bromides (0.25 mmol), Na2CO3 (0.95 mmol), Pd catalyst (0.001–1 mol%) and 1 mL of H2O/EtOH (v/v 1:1). The reaction mixture was vigorously stirred for a given reaction time. The reaction mixture slurry was subsequently diluted with 5 mL of H2O and 5 mL of dichloromethane (DCM) and filtered. The organic phase was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted twice with 5 mL of DCM. The combined organic layers were washed with 5 mL of water, and the organic solvent was removed under reduced pressure.

For the continuous flow reactions, a homogenous solution containing 4-bromobenzaldehyde, phenyl boronic acid and sodium carbonate in a H2O/EtOH (1:1) mixture at given concentrations was pumped through a 20 mL syringe using a PHD 2000 syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, UK) set at predetermined rates. During the reaction, approximately 30 drops of the product sample were collected at certain time intervals and subsequently extracted with 1 mL DCM. The conversion and yields were determined in the same way as mentioned previously.

Data availability statement

The authors declare all data available in manuscript and supporting information files.

References

Miyaura, N., Yamada, K. & Suzuki, A. A new stereospecific cross-coupling by the palladium-catalyzed reaction of 1-alkenylboranes with 1-alkenyl or 1-alkynyl halides. Tetrahedron Lett. 20, 3437–3440 (1979).

Miyaura, N. & Suzuki, A. Stereoselective synthesis of arylated (E)-alkenes by the reaction of alk-1-enylboranes with aryl halides in the presence of palladium catalyst. Chem. Comm. 19, 866–867 (1979).

Suzuki, A. Synthetic Studies via the cross-coupling reaction of organoboron derivatives with organic halides. Pure Appl. Chem. 63, 419–422 (1991).

Miyaura, N. & Suzuki, A. Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Organoboron Compounds. Chem. Rev. 95, 2457–2483 (1995).

Suzuki, A. Recent advances in the cross-coupling reactions of organoboron derivatives with organic electrophiles. J. Organomet. Chem. 576, 147–168 (1999).

Johansson Seechurn, C. C. C., Kitching, M. O., Colacot, T. J. & Snieckus, V. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling: a historical contextual perspective to the 2010 Nobel prize. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 5062–5085 (2012).

Molander, G. A. & Wolf, J. P. Science of Synthesis: Cross Coupling and Heck Type Reactions, (ed. Larhed, M.) Vols 1–3 (Stuttgart, 2013).

Meijere, A. & de Bräse, S. Metal Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions and More; (ed. Oestreich, M.) (Weinheim, 2014).

Churruca, F., SanMartin, R., Tellitu, I. & Domínguez, E. N-Heterocyclic NCN-pincer palladium complexes: a source for general, highly efficient catalysts in Heck, Suzuki, and Sonogashira coupling reactions. Synlett. 20, 3116–3120 (2005).

Inés, B. et al. A nonsymmetric pincer-type palladium catalyst in Suzuki, Sonogashira, and Hiyama couplings in neat water. Organometallics 27, 2833–2839 (2008).

Inés, B., Moreno, I., SanMartin, R. & Domínguez, E. A Nonsymmetric pincer-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura arylation of benzyl halides and other nonactivated unusual coupling partners. J. Org. Chem. 73, 8448–8451 (2008).

Gallon, B. J., Kojima, R. W., Kaner, R. B. & Diaconescu, P. L. Palladium nanoparticles supported on polyaniline nanofibers as a semi-heterogeneous catalyst in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 7251 (2007).

Wan, Y. et al. Ordered mesoporous Pd/silica-carbon as a highly active heterogeneous catalyst for coupling reaction of chlorobenzene in aqueous media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4541 (2009).

Casalnuovo, A. L. & Calabrese, J. C. Palladium-catalyzed alkylations in aqueous media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 4324–4330 (1990).

Ohtaka, A. Recyclable Polymer-Supported Nanometal Catalysts in Water. Chem. Rec. 13, 274–285 (2013).

Lipshutz, B. H., Petersen, T. B. & Abela, A. R. Room-Temperature Suzuki-Miyaura Couplings in Water Facilitated by Nonionic Amphiphile. Org. Lett. 10, 1333–1336 (2008).

Sharavath, V. & Ghosh, S. Palladium nanoparticles on noncovalently functionalized graphene-based heterogeneous catalyst for the Suzuki–Miyaura and Heck–Mizoroki reactions in water. RSC Adv. 4, 48322–48330 (2014).

Liu, L., Zhang, Y. & Wang, Y. Phosphine-Free Palladium Acetate Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction in Water. J. Org. Chem. 70, 6122–6125 (2005).

Totten, G. E. & Clinton, N. A. J. Macromol. Sci. Polymer Rev. 38, 77–142 (1998).

Ng, Y. H., Wang, M., Han, H. & Chai, C. L. L. Organic polymer composites as robust, non-covalent supports of metal salts. Chem. Commun. 5530–5532 (2009).

Kantam, M. L. et al. Polyaniline supported palladium catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of bromo- and chloroarenes in water. Tetrahedron 63, 8002–8009 (2007).

Zuo, Y. J. & Qu, J. How does aqueous solubility of organic reactant affect a water-promoted reaction? J. Org. Chem. 79, 6832–6839 (2014).

Röhlich, C., Wirth, A. S. & Köhler, K. Suzuki coupling reactions in neat water as the solvent: where in the biphasic reaction mixture do the catalytic reaction steps occur? Chem. Eur. J. 18, 15485–15494 (2012).

Chanda, A. & Fokin, V. V. Organic Synthesis “On Water”. Chem. Rev. 109, 725–748 (2009).

Lennox, A. J. J. & Lloyd-Jones, G. C. Transmetalation in the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling: the fork in the trail. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 7362–7370 (2013).

Knipping, E. M. et al. Experiments and simulations of ion-enhanced interfacial chemistry on aqueous NaCl aerosols. Science 288, 301–306 (2000).

Thomsen, K., Iliuta, M. C. & Rasmussen, P. Extended UNIQUAC model for correlation and prediction of vapour-liquid-liquid-solid equilibria in aqueous salt systems containing non-electrolytes. Part B. Alcohol (ethanol, propanols, butanols)-water-salt systems. Chem. Eng. Sci. 59, 3631–3647 (2004).

Jung, Y. & Marcus, R. A. On the theory of organic catalysis “on water”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5492–5502 (2007).

Narayan, S. et al. “On Water”: Unique Reactivity of Organic Compounds in Aqueous Suspension. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 3275–3279 (2005).

Mucha, M. et al. Unified molecular picture of the surfaces of aqueous acid, base, and salt solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 7617–7623 (2005).

Sigma-Aldrich,China, Pd EnCat™ encapsulated palladium catalysts, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/china-mainland/zh/technical-documents/articles/chemfiles/pd-encat-encapsulated0.html (2017).

Bortolotto, T. et al. Polymer-coated palladium nanoparticle catalysts for Suzuki coupling reactions. J. Colloid interface Sci. 439, 154–161 (2015).

Narayanan, R. & El-Sayed, M. A. Effect of catalysis on the stability of metallic nanoparticles: suzuki reaction catalyzed by PVP-palladium nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 8340–8347 (2003).

Winkler, K. et al. Structure and properties of C60–Pd films formed by electroreduction of C60 and palladium(II) acetate trimer: evidence for the presence of palladium nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 13, 518–525 (2003).

Elechiguerra, J. L. et al. Corrosion at the Nanoscale: The Case of Silver Nanowires and Nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 17, 6042–6052 (2005).

Bedford, R. B., Blake, M. E., Butts, C. P. & Holder, D. The Suzuki coupling of aryl chlorides in TBAB-water mixtures. Chem. Commun. 466–467 (2003).

Scott, R. W. J., Ye H., Henriquez, R. R. & Crooks, R. M. Synthesis, characterization, and stability of dendrimer-encapsulated palladium nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 3873–3878 (2003).

Diallo, A. K., Ornelas, C., Salmon, L., Aranzaes, J. R. & Astruc, D. Homeopathic catalytic activity and atom-leaching mechanism in Miyaura-Suzuki reactions under ambient conditions with precise dendrimer-stabilized Pd Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 8644–8648 (2007).

Bratlie, K. M., Lee, H., Komvopoulos, K., Yang, P. D. & Somorjai, G. A. Platinum nanoparticle shape effects on benzene hydrogenation selectivity. Nano Lett. 7, 3097–3101 (2007).

Ganesan, M., Freemantle, R. G. & Obare, S. O. Monodisperse thioether-stabilized palladium nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and reactivity. Chem. Mater. 19, 3464–3471 (2007).

Wang, C., Daimon, H., Onodera, T., Koda, T. & Sun, S. H. A general approach to the size- and shape-controlled synthesis of platinum nanoparticles and their catalytic reduction of oxygen. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3588–3591 (2008).

Sabbatini, L. Surface Characterization of Advanced Polymers. (ed. Zambonin, P. G.) (Weinheim, 1993).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Henan Collaborative Innovation Center of Molecular Diagnosis and Laboratory Medicine (XTCX-2015-ZD3), and Henan Educational Committee Program for Science and Technology Development of Universities (16A180015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: W.M., Y.H.J., and Performed the experiments: W.M., X.H., J.F. and Y.H.J. Analysed the data: W.M. and Y.H.J. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: W.M., X.H., J.F. and Y.H.J. Wrote the paper: W.M. and Y.H.J. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Xue, H., Ju, F. et al. Acceleration of Batch-type Heterogeneous Ligand-free Suzuki-Miyaura Reactions with Polymer Composite Supported Pd Catalyst. Sci Rep 7, 7006 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06499-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06499-z

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.