Abstract

Environmental stressors, gonadal degenerative diseases and tumour development can significantly alter the oocyte physiology, and species fertility and fitness. To expand the molecular understanding about oocyte degradation, we isolated several spliced variants of Japanese anchovy hatching enzymes (AcHEs; ovastacin homologue) 1 and 2, and analysed their potential in oocyte sustenance. Particularly, AcHE1b, an ovary-specific, steroid-regulated, methylation-dependent, stress-responsive isoform, was neofunctionalized to regulate autophagic oocyte degeneration. AcHE1a and 2 triggered apoptotic degeneration in vitellogenic and mature oocytes, respectively. Progesterone, starvation, and high temperature elevated the total degenerating oocyte population and AcHE1b transcription by hyper-demethylation. Overexpression, knockdown and intracellular zinc ion chelation study confirmed the functional significance of AcHE1b in autophagy induction, possibly to mitigate the stress effects in fish, via ion-homeostasis. Our finding chronicles the importance of AcHEs in stress-influenced apoptosis/autophagy cell fate decision and may prove significant in reproductive failure assessments, gonadal health maintenance and ovarian degenerative disease therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustainable species maintenance largely depends on the quality of eggs or oocytes. Gonadal atresia and oocyte degeneration are steroid responsive energy-sustaining phenomena, and are also widely acknowledged egg quality and reproductive success indicators in vertebrates1, 2. High throughput sequencing and functional genomics studies using zebrafish, salmonids and flat fish, emphasizes the importance of follicular atresia in vertebrate reproduction3,4,5. Despite the importance of germ cell/oocyte in reproduction and ovarian atresia3,4,5, little else is known about the molecular paradigm of atresia in oocytes.

Programmed cell death (PCD), first coined by Lockshin and Williams in 1964, is functionally important for several physiological processes, including gonadal maintenance and atresia6. Two pathways of PCD, apoptosis and autophagy, have been well characterized in several species7. While apoptosis and autophagy may occur together or distinctly, the expected outcome is the physiological removal of marked cells, leading to the development of new structures (morphogenesis), removal of damaged cells, and tissue homeostasis.

In vertebrate ovaries, gonadotropins, oestrogens, growth hormones, growth factors (IGF, EGF/TGFα, basic FGF), cytokines (interleukin-1β) and nitric oxide act in concert to ensure the survival of gonia and pre-ovulatory follicles6. However, in contrast, the ovarian androgens, interleukin-6 and gonadal GnRH-like peptides act as apoptotic factors8. Moreover, intra- and extracellular ion homeostasis of several divalent cations (Zn, Ca, etc.) have been reported to alter cellular atresia8, 9. Several metalloproteinases/choriolytic genes (ovastacin, hatching enzyme (HE), etc.) are also known to induce atresia in vertebrates10. In human, SAS1B (a.k.a ovastacin) is expressed in growing oocytes and uterine tumors, and has been postulated to be a major candidate for uterine tumor therapy11, 12. However, despite speculation and ovarian expression, the involvement of choriolytic genes in oocyte degeneration is still largely unknown11,12,13. Indepth knowledge of such phenomenon will advance the modus operandi required for egg quality assessment, gonadal degenerative disease therapy, and targeted ovarian or uterine cancer/tumor treatment.

Genomic duplication and alternative splicing are the two major driving forces for evolution14, 15. Evolutionarily, although fish occupies the lowest pane of vertebrate clade, it also possesses several attributes necessary to address complex research questions, thereby making these aquatic models efficacious for human disease study. Fish ovaries are a suitable experimental model system for studying PCD, due to the presence of both atretic and non-atretic oocytes5. Surprisingly, both human and rodent ovastacins are more similar to teleostean HE, than Xenopus HE10, thus rendering fish as an excellent alternative for exploring the pros and cons of mammalian ovarian atresia. Therefore, the present investigation was conducted to gain insight into the nature of the underlying molecular relationship of oocyte degeneration and hatching enzymes. The conserved oocyte specific expression profiles of hatching enzyme homologues across vertebrates urged us to focus only on the oocytes and not on the follicles.

Japanese anchovy (Engraulis japonicus) is a fast growing, heterogametic, primitive marine daily-breeding teleost, and possesses excellent demarcation between atretic and non-atretic oocytes. This fish has relatively large sized gonads, which gives it a unique advantage over the other relatively established models, i.e. zebrafish and medaka, to facilitate multiple experiments from the same gonad without any individual variations. Moreover, the previously identified five AcHE homologues were found to have significant role in embryonic chorion lysis16, which led us to hypothesize that at least some of the homologues might be essential for gonadal atresia, especially oocyte degeneration.

Results

Epigenetically regulated alternative splicing of HEs

Gonadal atresia, particularly chorionic degradation, involves a complex enzymatic regulation, similar to embryonic hatching16, 17. Donato et al.13 suggested the existence of hatching enzymes in atretic ovaries; however, the mechanisms underlying the hatching enzymes regulated gonadal degeneration has not yet been elucidated in detail. Furthermore, the existence of multiple isoforms of teleostean HEs makes it difficult to establish their specific importance in oocyte degeneration17, 18. In an attempt to gain additional insight, we measured the gonadal expression profiles of all existing AcHEs (Supplementary Fig. 1), and selected AcHE1 and 2 for further analysis. Alternative splicing is a useful mechanism for the post-transcriptional functional diversification of any specific gene, and plays a critical role in sexual development, ovarian maintenance and cell death, in various organisms15, 19,20,21,22,23. Thus, we explored the ovarian full-length cDNA library with various AcHE-specific primers and isolated spliced variants of AcHE1 and 2 (hereafter designated as AcHE1a, 1b, 2a, 2b and 2c, consisting of 273 (30.99KD), 208 (23.58KD), 276 (31.16KD), 300 (34.05KD) and 293aa (35.21KD), respectively) that possessed 3′ UTR of different sizes. Although all the isolated AcHE isoforms clustered into the type 1-hatching enzyme group (Supplementary Fig. 1), only AcHE1a and 2c were identical with the pre-reported AcHE1 and 2, respectively16 (Supplementary Table 1). Alternatively spliced variants of high coriolytic enzyme (HCE) were also recorded in medaka, which were clustered into the same phylogenetic group (Supplementary Fig. 1), and showed predominant ovarian expression (Data not shown). Our in silico putative protein analysis also showed different structural and folding patterns amongst the alternatively spliced isoforms (Fig. 1A–C, Supplementary Table 2). Differences in C-terminal lengths and alterations in the Astacin-extended-Zinc-binding domain (HEXXHXXGXXHEXXRXDR)16 suggests that varying translational differences, i.e. protein localization, protein folding, etc., are responsible for the functional diversity15.

Alternative splicing of AcHEs. In silico structural analysis of putative proteins depicted significant structural differences among AcHE1a (A), 1b (B) and 2a (C), especially in protein folding pattern in C-terminal region. Note: yellow asterisk (*) indicates the astacin (red ribbon shaped) domain. Schematic diagram show the alternative splicing of AcHE1 and 2, where, black boxes represents exon and dotted line indicates intron (D). Strong male dominated methylation of AcHE1, and not AcHE2, (E) was observed in Japanese anchovy adult gonads. Note: The graphical data are presented as percent mean ± SE; asterisk ‘#’ denotes significant sexual differences at each loci (P < 0.01); N = 15 individuals per sex, randomly collected from three distinct mature fish population @ 5/population; and the schematic diagram depicting the general methylation profile in female/male gonad and putative ERE (oestrogen responsive element) and PRE (progesterone responsive element) sites.

In order to clarify the role of the alternatively spliced isoforms in anchovy development and maturation, we evaluated tissue-biased mRNA profiles during adulthood. AcHE1a, 2a, 2b and 2c were predominant in the ovary and testis, whereas AcHE1b showed ovary-specific expression (Supplementary Fig. 2). Sex-dependent genomic methylation has been reported to regulate alternative splicing in various organisms24,25,26,27. To investigate further, we analyzed several intronic loci (depicted in silico) near the alternative splicing sites of both AcHE1 and 2 genes (Fig. 1D,E). More variable methylation was observed in AcHE1-intron-3 and AcHE2-intron-5 (harbouring alternative splicing sites) than their respective preceding introns (Fig. 1E, Supplementary Fig. 2). However, only AcHE1-intron-3 consistently depicted a sexually dimorphic methylation pattern (Fig. 1E), which proves that female-dominated AcHE1b expression is an outcome of the sex-biased methylation24,25,26,27.

The stage-specific occurrence of different spliced isoforms was observed during the course of ovarian development, with AcHE1a and 1b being abundant in immature ovaries, AcHE2a in atretic ovaries, and AcHE2b and 2c in all gonadal stages (Supplementary Fig. 2). A more comprehensive analysis using isolated oocytes (Fig. 2A) and in situ hybridization (ISH) (Supplementary Fig. 2) demonstrated that AcHE1 isoforms were predominant in immature and pre-atretic oocytes, while AcHE2 isoforms were mainly restricted to atretic oocytes. AcHE1 and 2 isoforms, but not AcHE3, 4 and 5, were undetected in the hydrated or ovulated oocytes (Supplementary Fig. 1). The varying expression patterns of AcHEs suggest that AcHE1 and 2 variants play some role in oocyte maintenance, while the other three isoforms are involved in the hatching mechanism. Genomic duplication and alternative splicing have been identified as the main navigators of neofunctionalization in eukaryotes14, 15, 28. Previously, predicted cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation sites (important for calcium ion channel maintenance in ovaries29) were markedly less prevalent in AcHE1b (Supplementary Table 2), which, in addition to sex-biased methylation and ovary-specific expression, insinuates the differential role of AcHE1b in ovarian maintenance28. Since we observed similar expression patterns for AcHE2b and 2c in different groups of female germ cells (Fig. 2A), we hereafter focused on the AcHE1a, 1b, 2a and 2b variants and their roles in oocyte maintenance and degeneration.

Steroidogenic alterations of AcHE in ovary. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) profiling determined the oocyte-stage responsive expression of AcHE isoforms in adult gonad (A). Progesterone treated gonads exhibited higher amplitude of AcHE1b, 2a and 2b transcription (B), and overall ovarian degeneration (C, black boundary) than other treatments (N = 12). The graphs are drawn using the ratio between treatment and controls (each separately normalized with respective internal control) of same time and stage. Sex steroid modulation altered the epimethylation status (N = 15) of AcHE1-intron-3 (D) and caused various extent of steroid responsive oocyte degeneration (E–G), thus suggesting that ovarian maturation and AcHE productions are interrelated. Fluorescent ISH (FISH) displayed the co-localization of AcHE1b and Beclin1 in various stages of oocytes of DHP treated gonad, (H). Note: Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and different letters (a, b, etc.) denotes significant differences at P < 0.05; significance was separately calculated for each loci in graph D, while for other graphs, the significance was calculated for each group. S1–S5 represents different atretic stages (Supplementary Fig. 3); PO- Primary oocyte; PN- Peri-nuclear oocyte; Inset microphotographs represents the respective control.

Steroid responsive modulation of HEs

In various animals, gonadal atresia is initiated just after the progesterone surge, thus highlighting progesterone-atresia inter-connections30, 31. The occurrence of AcHEs in pre-atretic and atretic ovaries raises the possibility of progesterone involvement in AcHE transcription. The introns of AcHE1 and 2 were found to possess several putative half-ERE and PRE32 sites (Fig. 1E). Upon maturation, teleostean females undergo major hormonal changes and the presence of putative steroid recognition sites increases the possibility of potential crosstalk between AcHEs and sex steroids. The involvement of oestrogen and progesterone in genomic demethylation has also been recently reported33. Depending on the concentration of these steroids, the methylation pattern may change, and induce atresia. To verify our hypothesis, we performed in vivo progesterone and 17α-20β-dihydroxy-4-pregnen-3-one (DHP, maturation-inducing hormone in fish34) treatments, and detected excessive genomic demethylation and abundant transcription of AcHE1b, 2a, and 2b, along with accelerated gonadal atresia (Fig. 2B–H), while mild increase was recorded at each time points in the control counterparts (Supplementary Table 3). Contrary to our expectations, the addition/suppression of oestrogen had lesser impact on AcHE transcription compared to progesterone and DHP. Thus, we concluded that although oestrogen initiated differential AcHE transcription, progesterone is necessary for excessive AcHE production and possibly for further induction of atresia.

Atresia and AcHE regulation

Gonadal atresia, a nutrient-circulating process, is activated in a synchronized manner and involves both autophagy and apoptosis7, 35. Starvation and high temperature (HT) are known to induce atresia in various animals36. In order to confirm the involvement of AcHEs in the initiation of autophagy/apoptosis, we examined the starved and HT-reared (27 and 30 °C) females, and observed significant time-dependent enhancements in AcHE1b transcription (Fig. 3A). This result further accentuated the crucial role of AcHE1b in the regulation of ovarian degeneration. Thereafter, we quantified the atretic cell population (Supplementary Fig. 3) and transcription of major atretic genes (P53, Beclin1 and LC3a, Fig. 3F), in order to validate the extent of the progression of atresia. Histologically, starved and HT-reared fish showed varying levels of atresia (Fig. 3B–D), depending on the level of stress5. AcHE1b expression was strongly correlated with stage 1 (S1) atretic oocytes (a slight break in the oocyte wall and excessive cell proliferation in the surrounding granulosa (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 4)) and autophagy markers (Beclin1 and LC3a) (Supplementary Table 5), while the other AcHE variants were more closely involved in apoptosis (P53) (Supplementary Table 5). This was further supported by the strong demethylation of AcHE1-intron-3 in HT-reared fish (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these results indicate that stressors induce varying levels of changes by the following pathways: (i) increased production of heat shock proteins (HSP) and their receptors, which subsequently promotes the production of several HSP-related cell death factors37, 38, and/or (ii) an accelerated demand for energy, which leads to glycogen breakdown, localized increments of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, phosphoenolpyruvate, and glucose-6-phosphate (enzymes for glucose production), and further increase in reactive oxygen species39. The latter pathway is known to involve autophagy instead of apoptosis39. We measured the amount of autophagosome formation (Fig. 3I) and autophagic protein (LC3 and ULK1) production (Fig. 3J), and found that both dramatically increased upon stress. Since we also observed stress-responsive co-induction of AcHE1b, Beclin1 and LC3a in the degenerating ovaries/oocytes (Fig. 3F–H), we speculate that AcHE1b favours autophagy during atresia.

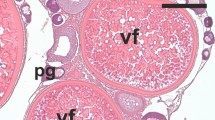

Role of AcHEs in ovarian atresia. Starvation and high temperature induced time-dependent AcHEs production (A), and moderate (C) to severe (D) oocyte degeneration compared to control (B). S1 atretic cell counts of starved (Y-axis 1) and 30 °C-reared (Y-axis 2) fish plotted against relative AcHE1b mRNA expression (in a polynomial trendline fit), showed positive correlation (E). Although, both apoptotic (P53) and autophagy (Beclin1 and LC3a) marker genes displayed strong modulations in various treatment groups (F), Tricolour FISH-FIHC revealed that AcHE1b (green colour; FISH) co-localized only with Beclin1 (red colour, FIHC) (G) but not with P53 (pink colour, FIHC) (H), highlighting the AcHE1b and autophagy interaction. Both autophagosome abundance (I) and autophagic protein production (J), but not P53 production (J), further corroborates the AcHE1b specific autophagy regulation. Note: Graphical data are presented as mean ± SEM, and different letters (a, b, etc.) denotes significant differences at P < 0.05. Oogonia (Og) and Primary oocyte (PO), Peri-nuclear oocyte (PN), cortical alveoli (CA), vitellogenic (VO), mature (MO) and atretic (AO) oocytes are marked accordingly. GADPH was used as internal control for western blotting.

Neofunctionalization of AcHE1b in autophagy

The involvement of AcHE1b in oocyte maintenance and autophagy regulation was ascertained by overexpressing AcHE1a/b-mCherry and AcHE2a/b-cyan at different oocyte stages, and monitoring the cellular degradation for 120h. Although AcHE1b induced extensive damage at all oocyte stages, AcHE1a triggered cell death in the vitellogenic and mature oocytes (Fig. 4A–G), while AcHE2a and 2b OV (overexpression) only degraded the late vitellogenic oocytes (Fig. 4A). A detailed time-dependent quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis (24, 72 and 120h post transfection, hpt) showed that AcHE1b induced Beclin1 and LC3a production, while all the other OV groups had an abundance of P53 expression (Supplementary Fig. 4). AcHE1a and 2a OV specifically triggered the expression of the other alternatively spliced isoforms and vice-versa (Fig. 4H–I). This might be due to some inbuilt defence mechanism against the extensive unidirectional progression of gonadal atresia. To further confirm the involvement of AcHE1b in autophagy, the knockdown (KD) of different AcHEs was performed, and the transcriptional and protein profiles of Beclin1, LC3 and P53, and ACHE production were assessed. AcHE1a KD gonads depicted elevated levels of AcHE1b, Beclin1 and LC3a, while AcHE1b KD samples portrayed higher levels of AcHE1a and P53 transcripts (Fig. 4J–N). Our fluorescent immunohistochemistry (FIHC) and western blotting data also displayed similar trend (Fig. 4M,I).

Functional analysis of AcHEs. Ex vivo AcHE OV induced various levels of oocyte mortality, highest in AcHE1b OV oocytes (A). Toluidine blue staining confirmed extensive degradation (‘#’) in AcHE1b OV oocytes (B) than their control counterpart (C). Live imaging of AcHE1a and 1b OV immature oocytes depicted strong reporter gene expression in ooplasm (D,F) (at 24 hpt) and extensive degeneration (white arrow, at 120 hpt) in AcHE1b OV transfected oocytes (G) only. The same oocytes were examined for cyan-βactin-UTR mRNA localization to confirm the extent of transfection (E). QPCR analysis of different overexpressed oocytes showed that AcHE1a/2a OV could, respectively, induce AcHE1b/2b transcription and vice-versa (H). The specificity of overexpression and knockdown were confirmed by western blotting with eel hatching enzyme antibody (I). The same blots were re-analysed with LC3 and P53 antibody to respectively confirm the autophagic and apoptotic responses (I). GADPH was used as internal control. In vivo AcHE1a/2a KD caused significant upregulation of autophagy genes while AcHE1b KD induced apoptosis, confirmed by Trichrome staining (J–L), FISH (M) and qPCR (N), Note: Graphical data are presented as mean ± SEM, and different letters (a, b, etc.) denotes significant differences at P < 0.05. Immature oocyte contains both peri-nuclear and chromatin nuclear oocytes. VTG = vitellogenic; Blue arrow denotes Beclin1 expression.

Cellular Zinc (Zn+2) concentrations and transport are critical for autophagy40. Depletion of intracellular Zn+2 by TPEN (N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis-(2-pyridylmethyl) ethylenediamine), but not cellular Zn+2 by DTPA (diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid), ensued the induction of apoptosis in the hepatocytes41. We added intracellular (TPEN) and extracellular (DPTA) Zn+2 chelator in the AcHE1b OV oocyte culture, and observed significant reduction in autophagy and simultaneous induction of apoptosis in the former, while no distinct changes were recorded in the latter (Fig. 5A–E). Interestingly, zinc inhibits Bax and Bak activation, cytochrome c release and other subsequent steps of apoptosis42 and favours AMPK activation43, thus triggering ULK-Beclin-LC3 mediated autophagy pathway. Moreover, P53 OV oocytes displayed extensive degeneration along with slight induction of AcHE1b, while Beclin1 OV oocytes did not show this induction (data not shown). Notably, different oocyte stages exhibited a ubiquitous expression of Beclin1 and LC3a, while P53 was only observed in the mature oocytes (Supplementary Fig. 4). This confirms that AcHE1b is present in various stages of oocytes and triggers autophagy, and further protects the fish from extensive oocyte degeneration, as and when required.

AcHE1b and Zinc (Zn+2) transport. AcHE1b OV immature oocytes were treated with intra (TPEN) or extra (DPTA) cellular Zn+2 chelator and the ratio of intra and extra cellular Zn+2 ion concentration, and AcHE1b, Beclin1 and P53 transcription (A) was measured. ULK1 and LC3 antibodies were used to confirm to extent of autophagy in DMSO (B), TPEN (C) and DPTA (D) treated AcHE1b OV oocytes. Western blotting analysis also substantiated the autophagic/apoptotic alterations (E). Our data suggests that AcHE1b regulates the Zn+2 ion balance, which further decides the cell fate. General mechanism of AcHE-atresia regulation is drawn based on our analysis (F).

Discussion

Genome duplication and differential alternative splicing are the two very important factors in teleostean functional diversification, that affects the expression, sub-cellular distribution, and functional activities of various gene products14, 15, 28. Unlike AcHE1b, other AcHEs did not show any sex-biased expression, which suggests their conserved role in several other sexually unrelated areas, i.e. hatching and sperm-oocyte interactions30, 44. The evolutionarily primitive status of Japanese anchovy, the complex exon-intron interaction-based diversification of HEs45 and the alternative splicing of AcHE1 likely emphasizes on the initiation of a neofunctionalization event. Follicular atresia and oocyte degeneration are well-known female-specific phenomena13, 46. Ovary-specific expression, female-biasness and steroid-responsive demethylation of AcHE1-intron-3, along with strong correlation with atretic oocytes, makes AcHE1b, a prime candidate for ovarian atresia regulation in Japanese anchovy. The ectopic OV and KD of AcHE1b, respectively, mimicked the two different modes of PCD, autophagy and apoptosis, and caused oocyte elimination.

Gonadal atresia, under both natural and stressful conditions, involves the sequential disintegration of oocyte germinal vesicles, cytoplasmic organelles and surrounding somatic cells, which are later removed by different independent machineries2. Previously, apoptosis was considered to be an active player in these physiological processes; however, recent biochemical and morphological evidence have revealed a more intricate involvement of autophagic cell death in oocyte elimination during atresia35, 47. The localization of transiently overexpressed AcHE1b in all stages of oocytes, along with the fact that ovarian autophagy is paramount to maintain the primordial oocyte pool in murine newborns35, 47, emphasizes the strong autophagy-AcHE1b relationship. This concept was further boosted by the strong correlation evidenced between AcHE1b and autophagy markers. Autophagy regulates apoptotic luteal cell death by controlling the Bax-to-Bcl-2 ratio and the subsequent activation of caspases48. Atresia induction or AcHEs OV in anchovy gonads elevated the expression of both apoptotic and autophagic genes. Furthermore, AcHE1a/2a OV gonads also showed a modest transcription of AcHE1b/2b, respectively, which together with the cogent association between P53 and AcHE1a/2a/2b isoforms, implies a strong concentration responsive inter-relationship between the different AcHE isoforms. These interconnections eventually promote gonadal degeneration by either skipping or adding autophagy to the process.

The steroidogenic regulation of gonadal atresia is not an uncommon phenomenon among vertebrates31, 49. DHP and AI (aromatase inhibitor) mediated altered methylation of the AcHE1 gene, and the strong progesterone-dependent upregulation of AcHE1b and autophagy markers, in addition to progesterone inducing autophagy by the mTOR pathway suppression50, confirms the involvement of steroids in gonadal atresia31, 49. In goat follicles, steroids regulate the Zn+2 concentrations, which is essential for hatching enzymes51 and autophagy40. Our work demonstrated the prevalence of several autophagic genes in AcHE1b expressing atretic oocytes. Since AcHEs are localized in the inner periphery of the chorion, and autophagic genes are specifically expressed in cell organelles, we presumed that some intermediary ion channel9, 40 or chemical cue (possibly responsive to different AcHE concentrations) is crucial for the induction of autophagy. Reversion of AcHE1b OV related autophagic effect by intracellular Zn+2 ion chelator, further strengthens the above hypothesis and also suggests that AcHE1b might be essential for zinc ion mediated autophagy maintenance in oocytes41,42,43. It is important to note that the addition of calcium (Ca+2) increased the germ cell survivability in medaka, reared at HT (unpublished data). The involvement of trace elements in autophagy8, 9, 40 and fewer cAMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation sites37 in AcHE1b, suggests that the HEs differentially trigger the uni/bidirectional ion flow and influence the cell elimination fate. Due to the differential steroid responsive transcription of AcHE, it is acceptable to assume that apoptosis/autophagy cell fate decision greatly depends on the alternatively splicing of HEs. However, the effects of several influencing factors, such as the nutritional and stress conditions of oocytes36, occurrence of follicular atresia and resorption52, whole body physiology46, ratios of different circulating steroids49 and the immune status of fish15, needs to be thoroughly investigated in order to clarify the consequences of stress on the reproductive success or failure of an organism.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The studies were carried out in accordance with the Institutional Ethics Committee of Ehime University, Ehime, Japan, strictly adhering to the guidelines set for the usage of animals by this committee. All in vivo experiments and fish maintenance were conducted following protocols and procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee at Ehime University, Japan. All surgeries were performed under Tricaine-S anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Experimental procedures

A detailed description of procedures used in this study is provided in Supplementary Information, Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Plasmid construction, sequence analysis, qPCR, histology, ISH and western blotting

All plasmids for ISH, qPCR standard preparation, and AcHE OV and KD, were constructed following previously published methodology53 with slight modification, wherever necessary (details in Supplementary Materials and Methods).

cDNA sequences of AcHE alternatively spliced isoforms were obtained from Japanese anchovy gonadal cDNA. Publically available database information were combined with laboratory generated data to obtain the phylogenetic tree, signal peptide and domain analysis, protein secondary structure and phosphorylation analysis, and 3D structure prediction15.

Changes in gene expression were quantified using the CFX-96 Realtime PCR system (Biorad, USA) using previously published protocols53, with minor modifications. The PCR conditions included an initial denaturation at 94 °C (2 min) followed by 40 cycles at 94 °C (30 s) and 60 °C (1 min). The geometric mean of ef1α and βactin were used to normalize the data.

Bouin fixed, paraffin embedded samples (at least 10 fish per group) were used for standard Hematoxylin & Eosin (HE) staining and fluorescent immunohistochemistry (FIHC), while, 4% paraformaldehyde fixed samples were used for ISH, Fluorescent ISH (FISH) and FISH-FIHC, using sense and anti-sense fluorescein or digoxigenin-labelled RNA probes (transcribed in vitro, using RNA labelling kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany))54, 55.

300 µg crude protein extract was loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Merck Millipore, German), blocked with PVDF blocking buffer (Toyobo, Japan), incubated with diluted antibody (1:10000) overnight, washed with TBST (20 mM tris-base, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% tween-20, pH 7.5), incubated with 1:20000 dilution of secondary goat anti-rabbit/mouse HRP-conjugated Ab (Vector Laboratories) for 1h and band revelations were achieved by Pierce ECL Plus Western Blot Kit (Thermofisher Scientific, Japan), while imaging was done using ImageQuant LAS-4000 (GE Healthcare, USA).

Experimental animals, designs, sample collection and data analysis

All the experiments were conducted using Adult Japanese anchovy maintained at 24 ± 2 °C, fed with commercially available feed (3 times a day, @ 4% body weight), if not otherwise mentioned, following Animal Care and Maintenance instructions of Ehime University Animal Use and Ethics Committee. Specifically, experimental groups were either starved, kept at high temperature (27 and 30 °C), fed with E2 (17β-estradiol, Wako, Japan, @ 10 mg kg−1 feed) or AI (aromatase inhibitor, Exemestine, GmBH, Germany, @ 100 mg kg−1 feed) mixed feed, injected with Progesterone (@100 ng/fish), DHP (@1 ng/fish), or transfected with AcHE, P53, Beclin1 antisense or sense mRNA (10 ng mRNA/individual) premixed with TransIT®-QR Delivery Solution (Mirus-bio,USA). All the experiments were conducted for 30 days, except Progesterone and DHP (6 days), AcHE (10 days), and P53 and Beclin1 (1day, followed by 3 days of in vitro culture) transfection. Individual fish were biopsied to assess the gonadal maturity status and phenotypic sex, and acclimatised (2 weeks) prior to the commencement of actual experiment. Steroid doses and other conditions were determined using a series of pilot experiments. Ontogeny samplings were carried out at 4 (immature), 5 (maturing), 6 (mature) months after fertilization (maf), and one half of each gonad was used for either qPCR or histological analysis.

All experiments were conducted for a minimum of three times, and One-Way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test, or Student’s t-test, was performed to assess the statistical differences of relative mRNA expression (using SPSS version 22). In the starvation, high temperature, E2, AI experiment, each tanks were used as replicate; while progesterone, DHP, AcHE KD exposed individuals were used as replicate. All experimental data are shown as mean ± SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05, if not otherwise mentioned. The correlations were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficient method.

Methylation analysis

Sex-biased methylation specific loci were identified using specific primers (designed using MethPrimer (http://www.urogene.org/cgi-bin/methprimer/methprimer.cgi)) of AcHE1 and AcHE2 intronic sequences (provided by Prof. Kawaguchi). Ovarian, testicular and experimental gonadal genomic DNAs were isolated, bisulfate treated using EZ methylation kit (Zymo, USA), PCR amplified using gene specific primers, cloned and sequenced. At least 5 gonads/experimental group/biological replicate were individually assessed, while 20 clones per gonad were used for sequence comparison.

Isolation and culture of female germ cells, overexpression of AcHEs, zinc ion estimation and autophagosome measurement

Germ cells and oocytes of five adult Japanese anchovy were enzymatically digested, gently suspended in L15 media (containing 1% FBS), chronologically sieved through 100, 40, 20, 5 μm mesh (Nytal, Switzerland), segregated using percoll (wherever necessary, to obtain early and late vitellogenic, immature and primary oocytes, and oogonia), separately cultured (100nos/well of 6 well dish) for 24 hours, using DMEM/F12 glutamax media (Gibco, USA) and 10% FBS (Gibco, USA), transfected with different AcHE overexpression plasmids (in triplicates) and analysed by confocal microscopy (Zeiss Axio 700), qPCR and histology. Controls were simultaneously prepared using empty vector transfected samples. Both isolation and transfection experiments were repeated for five times, and the averages of five different experiments were used for data analysis. Cells larger than 100 μm were further segregated into mid-vitellogenic, mature and hydrated fractions, using inverted microscope (Nikon, Japan), wherever necessary. Ovulated eggs were dissected out from five ovulating females during ovulation. Parallel experiments were conducted to ascertain the phenotypic degradation of cells (viable cell population) using tryphan blue stain (0.6 mg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature.

Similarly prepared and transfected (with AcHE1b OV plasmid) germ cells were treated (4 hpt) with either TPEN or DTPA (@1nM) Zn+2 ion Chelator56, and autophagic status were assessed by qPCR and FIHC. The cellular and medium zinc concentration was measured using Amplite™ Fluorimetric Zinc Ion Quantitation Kit (AAT bioquest), following manufacturer’s instructions.

Autophagosomes were measured using CYTO-ID Autophagy detection kit (Enzo, Japan), following manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, freshly dissociated cell mixture from different treatment groups were fixed with using 2% formaldehyde for 20 min, perforated with Glycine, washed with PBS, blocked using 2% FBS-PBS-0.001% Triton X for 1h, incubated with Alexa 488 tagged LC3 (1:300) antibody overnight, washed repeatedly, mounted on glass slides for microscopic observation and photomicrographed, using Axio-710 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany) and finally analysed using Image J software.

References

Mermillod, P. et al. Factors affecting oocyte quality: who is driving the follicle? Reprod. Domest. Anim. 43, 393–400 (2008).

Tingaud-Sequeira, A. et al. New insight into molecular pathways associated with flatfish ovarian development and atresia revealed by transcriptional analysis. BMC Genomics 10, 434 (2009).

Cerdà, J., Bobe, J., Babin, P. J., Admon, A. & Lubzens, E. Functional genomics and proteomic approaches for the study of gamete formation and viability in farmed finfish. Rev. Fish. Sci. 16(S1), 54–70 (2008).

Yamamoto, Y., Luckenbach, J. A., Young, G. & Swanson, P. Alterations in gene expression during fasting-induced atresia of early secondary ovarian follicles of coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 201, 1–11 (2016).

Thome, R. G. et al. Dual roles for autophagy during follicular atresia in fish ovary. Autophagy 5(1), 117–9 (2009).

Hsueh, A. J., Eisenhauer, K., Chun, S. Y., Hsu, S. Y. & Billig, H. Gonadal cell apoptosis. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 51, 433–55 (1996).

Morais, R. D., Thome, R. G., Lemos, F. S., Bazzoli, N. & Rizzo, E. Autophagy and apoptosis interplay during follicular atresia in fish ovary: a morphological and immunocytochemical study. Cell Tissue Res. 347(2), 467–78 (2012).

Kondratskyi, A. et al. Calcium-permeable ion channels in control of autophagy and cancer. Front. Physiol. 4, 272 (2013).

Bhardwaj, J. K. & Sharma, R. K. Changes in trace elements during follicular atresia in goat (Capra hircus) ovary. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 140(3), 291–8 (2011).

Quesada, V., Sanchez, L. M., Alvarez, J. & Lopez-Otin, C. Identification and characterization of human and mouse ovastacin: a novel metalloproteinase similar to hatching enzymes from arthropods, birds, amphibians, and fish. J. Biol. Chem. 279(25), 26627–34 (2004).

Pires, E. S. et al. Membrane associated cancer-oocyte neoantigen SAS1B/ovastacin is a candidate immunotherapeutic target for uterine tumors. Oncotarget 6(30), 30194–211 (2015).

Pires, E. S. et al. SAS1B protein [ovastacin] shows temporal and spatial restriction to oocytes in several eutherian orders and initiates translation at the primary to secondary follicle transition. Dev. Dyn. 242(12), 1405–26 (2013).

Donato, D. M. et al. Atresia in temperate basses: cloning of hatching enzyme (choriolysin) homologues from atretic ovaries. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 28(1), 329–30 (2003).

Sano, K., Kawaguchi, M., Watanabe, S. & Yasumasu, S. Neofunctionalization of a duplicate hatching enzyme gene during the evolution of teleost fishes. BMC Evol. Biol. 14, 221 (2014).

Mohapatra, S. et al. Steroid responsive regulation of IFNγ2 alternative splicing and its possible role in germ cell proliferation in medaka. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 400, 61–70 (2015).

Kawaguchi, M. et al. Different hatching strategies in embryos of two species, Pacific herring Clupea pallasii and Japanese anchovy Engraulis japonicus, that belong to the same order Clupeiformes, and their environmental adaptation. J. Exp. Zool. B: Mol. Dev. Evol. 312(2), 95–107 (2009).

Gomis-Ruth, F. X., Trillo-Muyo, S. & Stocker, W. Functional and structural insights into astacin metallopeptidases. Biol. Chem. 393(10), 1027–41 (2012).

Sterchi, E. E., Stocker, W. & Bond, J. S. Meprins, membrane-bound and secreted astacin metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med. 29(5), 309–28 (2008).

Chen, L., Bush, S. J., Tovar-Corona, J. M., Castillo-Morales, A. & Urrutia, A. O. Correcting for differential transcript coverage reveals a strong relationship between alternative splicing and organism complexity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31(6), 1402–13 (2014).

Hammes, A. et al. Two splice variants of the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene have distinct functions during sex determination and nephron formation. Cell 106(3), 319–29 (2001).

Krovel, A. V. & Olsen, L. C. Sexual dimorphic expression pattern of a splice variant of zebrafish vasa during gonadal development. Dev. Biol. 271(1), 190–7 (2004).

Yu, A. M., Idle, J. R., Herraiz, T., Küpfer, A. & Gonzalez, F. J. Screening for endogenous substrates reveals that CYP2D6 is a 5-methoxyindolethylamine O-demethylase. Pharmacogenetics 13(6), 307–19 (2003).

Ruirui, K. et al. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing, cell death, and cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. 158, 189–212 (2013).

Maunakea, A. K., Chepelev, I., Cui, K. & Zhao, K. Intragenic DNA methylation modulates alternative splicing by recruiting MeCP2 to promote exon recognition. Cell Res. 23, 1256–69 (2013).

Shao, C. et al. Epigenetic modification and inheritance in sexual reversal of fish. Genome Res. 24, 604–15 (2014).

Wang, X., Werren, J. H. & Clark, A. G. Genetic and epigenetic architecture of sex-biased expression in the jewel wasps Nasonia vitripennis and giraulti. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 112(27), E3545–54 (2015).

Yearim, A. et al. HP1 is involved in regulating the global impact of DNA methylation on alternative splicing. Cell Rep. 10(7), 1122–34 (2015).

Schwerk, C. & Schulze-Osthoff, K. Regulation of apoptosis by alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell. 19(1), 1–13 (2005).

Tosti, E. Calcium ion currents mediating oocyte maturation events. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 4, 26 (2006).

Chaffin, C. L. & Stouffer, R. L. Role of gonadotrophins and progesterone in the regulation of morphological remodelling and atresia in the monkey peri-ovulatory follicle. Hum. Reprod. 15(12), 2489–95 (2000).

Nishiyama, M., Chiba, H., Uchida, K., Shimotani, T. & Nozaki, M. Relationships between plasma concentrations of sex steroid hormones and gonadal development in the brown hagfish, Paramyxine atami. Zoolog. Sci. 30(11), 967–74 (2013).

Yin, P. et al. Genome-wide progesterone receptor binding: cell type-specific and shared mechanisms in T47D breast cancer cells and primary leiomyoma cells. PLoS One 7(1), e29021 (2012).

Li, L. et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor status affect genome wide DNA methylation profile in breast cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19(21), 4273–7 (2010).

Nagahama, Y. & Yamashita, M. Regulation of oocyte maturation in fish. Dev. Growth Differ. 50, S195–219 (2008).

Escobar, M. L., Echeverría, O. M. & Vázquez-Nin, G. H. Role of Autophagy in the Ovary Cell Death in Mammals. Autophagy - A Double-Edged Sword - Cell Survival or Death? eds Bailly, Y. (InTech) ISBN: doi:10.5772/54777 (2013).

Corriero, A. et al. Evidence that severe acute stress and starvation induce rapid atresia of ovarian vitellogenic follicles in Atlantic bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus (L.) (Osteichthyes: Scombridae). J. Fish Dis. 34(11), 853–60 (2011).

Takayama, S., Reed, J. C. & Homma, S. Heat-shock proteins as regulators of apoptosis. Oncogene 22(56), 9041–7 (2003).

Song, X., Chen, Z., Wu, C. & Zhao, S. Abrogating HSP response augments cell death induced by As2O3 in glioma cell lines. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 37(4), 504–11 (2010).

Berger, L. & Wilde, A. Glycolytic metabolites are critical modulators of oocyte maturation and viability. PLoS One 8(10), e77612 (2013).

Liuzzi, J. P., Guo, L., Yoo, C. & Stewart, T. S. Zinc and autophagy. Biometals 27(6), 1087–96 (2014).

Nakatani, T., Tawaramoto, M., Opare Kennedy, D., Kojima, A. & Matsui-Yuasa, I. Apoptosis induced by chelation of intracellular zinc is associated with depletion of cellular reduced glutathione level in rat hepatocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 125(3), 151–63 (2000).

Ganju, N. & Eastman, A. Zinc inhibits Bax and Bak activation and cytochrome c release induced by chemical inducers of apoptosis but not by death-receptor-initiated pathways. Cell Death Differ. 10(6), 652–61 (2003).

Eom, J. W., Lee, J. M., Koh, J. Y. & Kim, Y. H. AMP-activated protein kinase contributes to zinc-induced neuronal death via activation by LKB1 and induction of Bim in mouse cortical cultures. Mol. Brain 9, 14 (2016).

Sano, K. et al. Purification and characterization of zebrafish hatching enzyme – an evolutionary aspect of the mechanism of egg envelope digestion. FEBS. J. 275(23), 5934–46 (2008).

Kawaguchi, M. et al. Remarkable consistency of exon-intron structure of hatching enzyme genes and molecular phylogenetic relationships of teleostean fishes. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 94(3), 567–76 (2012).

Townson, D. H. & Combelles, C. M. H. Ovarian Follicular Atresia. Basic Gynecology - Some Related Issues, eds Darwish, A. (InTech), doi:10.5772/2252 (2012).

Gawriluk, T. R. et al. Autophagy is a cell survival program for female germ cells in the murine ovary. Reproduction 141(6), 759–65 (2011).

Choi, J., Jo, M., Lee, E. & Choi, D. Induction of apoptotic cell death via accumulation of autophagosomes in rat granulosa cells. Fertil. Steril. 95(4), 1482–6 (2011).

Goldman, S. & Shalev, E. Progesterone receptor isoforms profile, modulate matrix metalloproteinase 2 expression in the decidua. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 197(6), 604.e1–8 (2007).

Zielniok, K., Motyl, T. & Gajewska, M. Functional interaction between 17β- estradiol and progesterone regulate autophagy during acini formation by bovine mammary epithelial cells in 3D cultures. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 382653 (2014).

Hannon, P. R., Brannick, K. E., Wang, W., Gupta, R. K. & Flaws, J. A. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate inhibits antral follicle growth, induces atresia, and inhibits steroid hormone production in cultured mouse antral follicles. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 284(1), 42–53 (2015).

Matsuda, F., Inoue, N., Manabe, N. & Ohkura, S. Follicular growth and atresia in mammalian ovaries: regulation by survival and death of granulosa cells. J. Reprod. Dev. 58(1), 44–50 (2012).

Chakraborty, T., Zhou, L. Y., Chaudhari, A., Iguchi, T. & Nagahama, Y. Dmy initiates masculinity by altering Gsdf/Sox9a2/Rspo1 expression in medaka (Oryzias latipes). Sci. Rep. 6, 19480 (2016).

Chakraborty, T. et al. Different expression of three estrogen receptor subtype mRNAs in gonads and liver from embryos to adults of the medaka. Oryzias latipes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 333(1), 47–54 (2011).

Zhou, L. Y. et al. Rspo1-activated signalling molecules are sufficient to induce ovarian differentiation in XY medaka (Oryzias latipes). Sci. Rep. 6, 19543 (2016).

Cho, Y. E. et al. Zinc deficiency negatively affects alkaline phosphatase and the concentration of Ca, Mg and P in rats. Nutr. Res. Pract. 1(2), 113–9 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. M. Kawaguchi (Sophia University, Japan), Dr. Craig V. Sullivan (Carolina AquaGyn, USA), and Dr. R. Goto (Ehime University, Japan) for their help. We also sincerely thank Mr. K. Ohno and Mr. M. Tanaka of Ehime University, Japan, for maintaining Japanese anchovy for the experiments. This work was in part supported by Grants from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan; Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Kakenhi, Grant Nos. 23688022, 16804981 and 23380110; and Ehime University Post-Doctoral Research Grant, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.C., S.M. & M.T. contributed equally to this work. T.C., S.M., L.Z. & T.M. conceived & designed research. T.C., S.M. & M.T. performed most of the experiments. Ka.O. conducted ontogeny analysis, Y.-W.R. maintained the fish stock, Y.K. helped in different plasmid designing, construction and validation. T.C., K.O., L.Z., Y.N. & T.M. provided chemicals and materials for experiments. T.C., S.M. & K.O. performed statistical analyses. T.C., S.M. & Y.N. prepared manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chakraborty, T., Mohapatra, S., Tobayama, M. et al. Hatching enzymes disrupt aberrant gonadal degeneration by the autophagy/apoptosis cell fate decision. Sci Rep 7, 3183 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03314-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03314-7

This article is cited by

-

Molecular cloning, characterization, and expression patterns of the hatching enzyme genes during embryonic development of pikeperch (Sander lucioperca)

Aquaculture International (2023)

-

Translocation of promoter-conserved hatching enzyme genes with intron-loss provides a new insight in the role of retrocopy during teleostean evolution

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.