Abstract

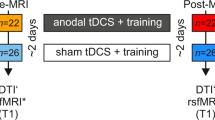

Cognitive training and brain stimulation show promise for ameliorating age-related neurocognitive decline. However, evidence for this is controversial. In a Registered Report, we investigated the effects of these interventions, where 133 older adults were allocated to four groups (left prefrontal cortex anodal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) with decision-making training, and three control groups) and trained over 5 days. They completed a task/questionnaire battery pre- and post-training, and at 1- and 3-month follow-ups. COMT and BDNF Val/Met polymorphisms were also assessed. Contrary to work in younger adults, there was evidence against tDCS-induced training enhancement on the decision-making task. Moreover, there was evidence against transfer of training gains to untrained tasks or everyday function measures at any post-intervention time points. As indicated by exploratory work, individual differences may have influenced outcomes. But, overall, the current decision-making training and tDCS protocol appears unlikely to lead to benefits for older adults.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data files are available at: https://osf.io/e2u73.

Code availability

Analysis code is provided at: https://osf.io/e2u73.

References

United Nations Development Programme. Human development report 2013: the rise of the South: human progress in a diverse world http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/14/hdr2013_en_complete.pdf (2013)

Park, D. C. & Reuter-Lorenz, P. The adaptive brain: aging and neurocognitive scaffolding. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60, 173–196 (2009).

Harper, S. Ageing Societies (Routledge, 2014).

Kievit, R. A. et al. Distinct aspects of frontal lobe structure mediate age-related differences in fluid intelligence and multitasking. Nat. Commun. 5, 5658 (2014).

DeCarli, C. Mild cognitive impairment: prevalence, prognosis, aetiology, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2, 15–21 (2003).

Kramer, J. H. et al. Longitudinal MRI and cognitive change in healthy elderly. Neuropsychology 21, 412–418 (2007).

Mungas, D. et al. Longitudinal volumetric MRI change and rate of cognitive decline. Neurology 65, 565–571 (2005).

Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 64, 135–168 (2013).

Cahn-Weiner, D. A., Boyle, P. A. & Malloy, P. F. Tests of executive function predict instrumental activities of daily living in community-dwelling older individuals. Appl. Neuropsychol. 9, 187–191 (2002).

Grigsby, J., Kaye, K., Baxter, J., Shetterly, S. M. & Hamman, R. F. Executive cognitive abilities and functional status among community-dwelling older persons in the San Luis Valley health and aging study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 46, 590–596 (1998).

Perceval, G., Flöel, A. & Meinzer, M. Can transcranial direct current stimulation counteract age-associated functional impairment? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 65, 157–172 (2016).

Jones, K. T., Stephens, J. A., Alam, M., Bikson, M. & Berryhill, M. E. Longitudinal neurostimulation in older adults improves working memory. PLoS ONE 10, e0121904 (2015).

Stephens, J. A. & Berryhill, M. E. Older adults improve on everyday tasks after working memory training and neurostimulation. Brain Stimul. 9, 553–559 (2016).

Flöel, A., Rösser, N., Michka, O., Knecht, S. & Breitenstein, C. Noninvasive brain stimulation improves language learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20, 1415–1422 (2008).

Meinzer, M., Lindenberg, R., Antonenko, D., Flaisch, T. & Floel, A. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation temporarily reverses age-associated cognitive decline and functional brain activity changes. J. Neurosci. 33, 12470–12478 (2013).

Cohen Kadosh, R., Soskic, S., Iuculano, T., Kanai, R. & Walsh, V. Modulating neuronal activity produces specific and long-lasting changes in numerical competence. Curr. Biol. 20, 2016–2020 (2010).

Iuculano, T. & Cohen Kadosh, R. The mental cost of cognitive enhancement. J. Neurosci. 33, 4482 (2013).

Holland, R. & Crinion, J. Can tDCS enhance treatment of aphasia after stroke? Aphasiology 26, 1169–1191 (2012).

Manor, B. et al. Reduction of dual-task costs by noninvasive modulation of prefrontal activity in healthy elders. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 28, 275–281 (2015).

Harty, S. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation over right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex enhances error awareness in older age. J. Neurosci. 34, 3646 (2014).

Filmer, H. L., Varghese, E., Hawkins, G. E., Mattingley, J. B. & Dux, P. E. Improvements in attention and decision-making following combined behavioral training and brain stimulation. Cereb. Cortex 27, 3675–3682 (2017).

Russo, R., Wallace, D., Fitzgerald, P. B. & Cooper, N. R. Perception of comfort during active and sham transcranial direct current stimulation: a double blind study. Brain Stimul. 6, 946–951 (2013).

Horvath, J. C., Carter, O. & Forte, J. D. Transcranial direct current stimulation: five important issues we aren’t discussing (but probably should be). Front. Syst. Neurosci. 8, 2 (2014).

O’Connell, N. E. et al. Rethinking clinical trials of transcranial direct current stimulation: participant and assessor blinding is inadequate at intensities of 2mA. PLoS ONE 7, e47514 (2012).

Filmer, H. L., Dux, P. E. & Mattingley, J. B. Applications of transcranial direct current stimulation for understanding brain function. Trends Neurosci. 37, 742–753 (2014).

Nilsson, J., Lebedev, A. V., Rydström, A. & Lövdén, M. Direct-current stimulation does little to improve the outcome of working memory training in older adults. Psychol. Sci. 28, 907–920 (2017).

Mancuso, L. E., Ilieva, I. P., Hamilton, R. H. & Farah, M. J. Does transcranial direct current stimulation improve healthy working memory?: A meta-analytic review. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 28, 1063–1089 (2016).

Chambers, C. The Seven Deadly Sins of Psychology: A Manifesto for Reforming the Culture of Scientific Practice (Princeton Univ. Press, 2017).

Antal, A. et al. Low intensity transcranial electric stimulation: safety, ethical, legal regulatory and application guidelines. Clin. Neurophysiol. 128, 1774–1809 (2017).

Wagenmakers, E.-J. et al. Bayesian inference for psychology, part I: theoretical advantages and practical ramifications. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 25, 35–37 (2018).

Jeffreys, H. The Theory of Probability (Oxford Univ. Press, 1961).

Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, R. D. & Iverson, G. Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 16, 225–237 (2009).

Berryhill, M. E. & Jones, K. T. tDCS selectively improves working memory in older adults with more education. Neurosci. Lett. 521, 148–151 (2012).

Learmonth, G., Thut, G., Benwell, C. S. Y. & Harvey, M. The implications of state-dependent tDCS effects in aging: behavioural response is determined by baseline performance. Neuropsychologia 74, 108–119 (2015).

Perceval, G., Martin, A. K., Copland, D. A., Laine, M. & Meinzer, M. Multisession transcranial direct current stimulation facilitates verbal learning and memory consolidation in young and older adults. Brain Lang. 205, 104788 (2020).

Arciniega, H., Gözenman, F., Jones, K. T., Stephens, J. A. & Berryhill, M. E. Frontoparietal tDCS benefits visual working memory in older adults with low working memory capacity. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 57 (2018).

Woods, A., et al. in Practical Guide to Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (eds. Knotkova, H., Nitsche, M. A., Biksom, M. & Woods, A.) 569–595 (Springer International, 2019).

Indahlastari, A. et al. Modeling transcranial electrical stimulation in the aging brain. Brain Stimul. 13, 664–674 (2020).

Emonson, M. R. L., Fitzgerald, P. B., Rogasch, N. C. & Hoy, K. E. Neurobiological effects of transcranial direct current stimulation in younger adults, older adults and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia 125, 51–61 (2019).

Mahdavi, S. & Towhidkhah, F. Computational human head models of tDCS: influence of brain atrophy on current density distribution. Brain Stimul. 11, 104–107 (2018).

Yu, J., Lam, C. L., Man, I. S., Shao, R. & Lee, T. M. Multi-session anodal prefrontal transcranial direct current stimulation does not improve executive functions among older adults. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 26, 372–381 (2019).

Hanley, C. & Tales, A. Anodal tDCS improves attentional control in older adults. Brain Stimul. 12, 399 (2019).

Batsikadze, G., Moliadze, V., Paulus, W., Kuo, M. F. & Nitsche, M. A. Partially non-linear stimulation intensity-dependent effects of direct current stimulation on motor cortex excitability in humans. J. Physiol. 591, 1987–2000 (2013).

Reato, D. et al. in Practical Guide to Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation: Principles, Procedures and Applications (eds. H. Knotkova, M. A. Nitsche, M. Bikson, & A. J. Woods) 45–80 (Springer International, 2019).

Boggio, P. S. et al. Modulation of decision-making in a gambling task in older adults with transcranial direct current stimulation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 31, 593–597 (2010).

Fertonani, A., Brambilla, M., Cotelli, M. & Miniussi, C. The timing of cognitive plasticity in physiological aging: a tDCS study of naming. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 131 (2014).

Manenti, R., Brambilla, M., Petesi, M., Ferrari, C. & Cotelli, M. Enhancing verbal episodic memory in older and young subjects after non-invasive brain stimulation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 5, 49 (2013).

Bikson, M. & Datta, A. Guidelines for precise and accurate computational models of tDCS. Brain Stimul. 5, 430–431 (2012).

Raz, N., Rodrigue, K. M., Kennedy, K. M. & Land, S. Genetic and vascular modifiers of age-sensitive cognitive skills: effects of COMT, BDNF, ApoE, and hypertension. Neuropsychology 23, 105–116 (2009).

Plewnia, C. et al. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on executive functions: influence of COMT Val/Met polymorphism. Cortex 49, 1801–1807 (2013).

Puri, R. et al. Duration-dependent effects of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on anodal tDCS induced motor cortex plasticity in older adults: a group and individual perspective. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7, 107 (2015).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113 (1971).

Dipietro, L., Caspersen, C. J., Ostfeld, A. M. & Nadel, E. R. A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 25, 628–642 (1993).

Barnett, S. M. & Ceci, S. J. When and where do we apply what we learn?: A taxonomy for far transfer. Psychol. Bull. 128, 612–637 (2002).

Kennedy, K. M. & Raz, N. Aging white matter and cognition: differential effects of regional variations in diffusion properties on memory, executive functions, and speed. Neuropsychologia 47, 916–927 (2009).

Bherer, L. et al. Training effects on dual-task performance: are there age-related differences in plasticity of attentional control? Psychol. Aging 20, 695–709 (2005).

Dux, P. E., Asplund, C. L. & Marois, R. Both exogenous and endogenous target salience manipulations support resource depletion accounts of the attentional blink. J. Vis. 9, 120–120 (2009).

Potter, M. C. Short-term conceptual memory for pictures. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 2, 509 (1976).

Potter, M. C. Very short-term conceptual memory. Mem. Cogn. 21, 156–161 (1993).

Lahar, C. J., Isaak, M. I. & McArthur, A. D. Age differences in the magnitude of the attentional blink. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 8, 149–159 (2001).

Bender, A., Filmer, H., Garner, K., Naughtin, C. & Dux, P. On the relationship between response selection and response inhibition: an individual differences approach. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 78, 2420–2432 (2016).

Unsworth, N., Heitz, R., Schrock, J. & Engle, R. An automated version of the operation span task. Behav. Res. Methods 37, 498–505 (2005).

Rush, B. K., Barch, D. M. & Braver, T. S. Accounting for cognitive aging: context processing, inhibition or processing speed? Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 13, 588–610 (2006).

Madden, D. J. Aging and visual attention. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 16, 70–74 (2007).

Heaton, R. K., PAR Staff. Wisconsin card sorting test: Computer version 4-research edition (WCST: CV4) (PAR, 2003).

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y. & Plumb, I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 42, 241 (2001).

Gunning-Dixon, F. M. & Raz, N. Neuroanatomical correlates of selected executive functions in middle-aged and older adults: a prospective MRI study. Neuropsychologia 41, 1929–1941 (2003).

Luck, T. et al. Prevalence of DSM-5 mild neurocognitive disorder in dementia-free older adults: results of the population-based LIFE-Adult-Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 25, 328–339 (2017).

Boggio, P. S. et al. Temporal cortex direct current stimulation enhances performance on a visual recognition memory task in Alzheimer disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 80, 444–447 (2009).

Rami, L. et al. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on memory subtypes: a controlled study. Neuropsychologia 41, 1877–1883 (2003).

Floel, A. et al. Prefrontal cortex asymmetry for memory encoding of words and abstract shapes. Cereb. Cortex 14, 404–409 (2004).

Rossi, S. et al. Prefontal cortex in long-term memory: an “interference” approach using magnetic stimulation. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 948–952 (2001).

Sandrini, M., Cappa, S. F., Rossi, S., Rossini, P. M. & Miniussi, C. The role of prefrontal cortex in verbal episodic memory: rTMS evidence. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 15, 855–861 (2003).

Epstein, C. M., Sekino, M., Yamaguchi, K., Kamiya, S. & Ueno, S. Asymmetries of prefrontal cortex in human episodic memory: effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on learning abstract patterns. Neurosci. Lett. 320, 5–8 (2002).

Brady, T. F., Konkle, T., Alvarez, G. A. & Oliva, A. Visual long-term memory has a massive storage capacity for object details. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14325–14329 (2008).

Anguera, J. A. et al. Video game training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature 501, 97–101 (2013).

Hinton-Bayre, A. & Geffen, G. Comparability, reliability, and practice effects on alternate forms of the digit symbol substitution and symbol digit modalities tests. Psychol. Assess. 17, 237 (2005).

Roth, R. M., Isquith, P. K. and Gioia, G. A. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Adult Version: Professional Manual (Psychological Assessment Resources, 2005).

Holbrook, M. & Skilbeck, C. E. An activities index for use with stroke patients. Age Ageing 12, 166–170 (1983).

Turnbull, J. C. et al. Validation of the Frenchay Activities Index in a general population aged 16 years and older. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 81, 1034–1038 (2000).

Hawi, Z., Millar, N., Daly, G., Fitzgerald, M. & Gill, M. No association between catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene polymorphism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in an Irish sample. Am. J. Med. Genet. 96, 282–284 (2000).

Klem, G. H., Lüders, H. O., Jasper, H. & Elger, C. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 52, 3–6 (1999).

Dux, P. E., Ivanoff, J., Asplund, C. L. & Marois, R. Isolation of a central bottleneck of information processing with time-resolved fMRI. Neuron 52, 1109–1120 (2006).

Dux, P. E. et al. Training improves multitasking performance by increasing the speed of information processing in human prefrontal cortex. Neuron 63, 127–138 (2009).

Filmer, H. L., Mattingley, J. B. & Dux, P. E. Improved multitasking following prefrontal tDCS. Cortex 49, 2845–2852 (2013).

Park, S.-H., Seo, J.-H., Kim, Y.-H. & Ko, M.-H. Long-term effects of transcranial direct current stimulation combined with computer-assisted cognitive training in healthy older adults. NeuroReport 25, 122–126 (2014).

Fregni, F. et al. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex enhances working memory. Exp. Brain Res. 166, 23–30 (2005).

Boggio, P. S., Zaghi, S., Lopes, M. & Fregni, F. Modulatory effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on perception and pain thresholds in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Neurol. 15, 1124–1130 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank our research assistant A. Fox, who contributed substantially to data collection. P.E.D. and J.B.M. were supported by an ARC grant (DP180101885), H.L.F. by a UQ Fellowship (UQFEL1607881) and ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE190100299). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.H. was involved in all aspects of the study, including study design, project planning, recruitment and data collection, data analysis and manuscript preparation. H.L.F. also contributed to each of these aspects. Z.E.N. contributed to project planning and data collection. Z.H. and K.P. were responsible for extraction and analysis of genetic data. J.B.M. contributed to study design and manuscript preparation. P.E.D. was involved in study design, project planning, data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: Anne Marike-Schiffer.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Individual task and questionnaire statistics for one way ANOVA on baseline performance.

Note: BF >10 indicates strong support for H1 over H0; BF >3 indicates moderate support for H1 over H0; 1< BF <3 indicates anecdotal support for H1 over H0; 1/3< BF <1 indicates anecdotal support for H0 over H1; 1/10< BF <1/3 indicates moderate support for H0 over H1; BF <1/10 indicates strong evidence for H0 over H1; BF = 1 indicates no evidence for H0 or H1.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Individual task and questionnaire statistics for the group x time interaction for all time points.

Note: BF >10 indicates strong support for H1 over H0; BF >3 indicates moderate support for H1 over H0; 1< BF <3 indicates anecdotal support for H1 over H0; 1/3< BF <1 indicates anecdotal support for H0 over H1; 1/10< BF <1/3 indicates moderate support for H0 over H1; BF <1/10 indicates strong evidence for H0 over H1; BF = 1 indicates no evidence for H0 or H1.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Individual task statistics for the effect of genotype on baseline performance.

Note: COMT statistics are derived from one-way ANOVAs and BDNF statistics are derived from independent samples t-tests due to the exclusion of Met/Met alleles from analyses. BF >10 indicates strong support for H1 over H0; BF >3 indicates moderate support for H1 over H0; 1< BF <3 indicates anecdotal support for H1 over H0; 1/3< BF <1 indicates anecdotal support for H0 over H1; 1/10< BF <1/3 indicates moderate support for H0 over H1; BF <1/10 indicates strong evidence for H0 over H1; BF = 1 indicates no evidence for H0 or H1.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Individual task statistics for the genotype x group x time interaction.

Note: COMT statistics are derived from one-way ANOVAs and BDNF statistics are derived from independent samples t-tests due to the exclusion of Met/Met alleles from analyses. BF >10 indicates strong support for H1 over H0; BF >3 indicates moderate support for H1 over H0; 1< BF <3 indicates anecdotal support for H1 over H0; 1/3< BF <1 indicates anecdotal support for H0 over H1; 1/10< BF <1/3 indicates moderate support for H0 over H1; BF <1/10 indicates strong evidence for H0 over H1; BF = 1 indicates no evidence for H0 or H1.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figs. 1–16 and Supplementary References.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Horne, K.S., Filmer, H.L., Nott, Z.E. et al. Evidence against benefits from cognitive training and transcranial direct current stimulation in healthy older adults. Nat Hum Behav 5, 146–158 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00979-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00979-5

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the impact of intensified multiple session tDCS over the left DLPFC on brain function in MCI: a randomized control trial

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Microstructural and functional plasticity following repeated brain stimulation during cognitive training in older adults

Nature Communications (2023)

-

A systematic review and meta-analysis of transcranial direct-current stimulation effects on cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s disease

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)

-

Strategies to Promote Cognitive Health in Aging: Recent Evidence and Innovations

Current Psychiatry Reports (2022)

-

Self-reported Outcome Expectations of Non-invasive Brain Stimulation Are Malleable: a Registered Report that Replicates and Extends Rabipour et al. (2017)

Journal of Cognitive Enhancement (2022)