Abstract

The Montreal Protocol and its successive amendments have been successful in curbing emissions of ozone-depleting substances and potent greenhouse gases via production/consumption controls. Here we show that the radiative forcing and equivalent effective chlorine from hydrochlorofluorocarbons has decreased from 61.75 mW m−2 and 321.69 ppt, respectively, since 2021, 5 years before the most recent projected decrease. This important milestone demonstrates the benefits of the Protocol for mitigating climate change and stratospheric ozone layer loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Following evidence that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) released to the atmosphere cause the depletion of stratospheric ozone1, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was enacted to control the production and consumption of CFCs and other ozone-depleting substances (ODSs). With numerous amendments and adjustments to the Protocol, which was first adopted in 1987, the global phase out of the production of CFCs was completed in 2010. Because of these controls, and other anticipated reductions in future ODS emissions, Antarctic ozone (a common measure for ozone layer recovery) is estimated to return to 1980 levels shortly after the middle of the current century2.

CFCs were initially replaced by hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), primarily for refrigeration, air conditioning and blowing of foam insulation where non-ozone-depleting alternatives, for example, propane in domestic refrigeration, could not be found. While HCFCs have much lower ozone depletion potentials than the CFCs they replaced, they are still ODSs and potent greenhouse gases; HCFC-22, the most abundant HCFC in the atmosphere, has a global warming potential 1,910 times that of carbon dioxide on a 100 year time horizon3. Since non-ozone-depleting alternatives became available, for example hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), a phaseout of the production and consumption of HCFCs was mandated by the Copenhagen (1992) and Beijing (1999) Amendments to the Montreal Protocol and will be completed globally by 2040.

While the Montreal Protocol was introduced to safeguard stratospheric ozone through the phaseout of consumption and production of long-lived CFCs, which have high global warming potentials, it has also avoided substantial global warming4,5. The total direct radiative forcing due to CFCs in the atmosphere peaked in 2000 (ref. 6). Despite exceptional cases where emissions or atmospheric abundances of certain CFCs have increased, either through illicit production, emissions from processes allowed under the Montreal Protocol, or unknown reasons7,8,9, the overall trajectory for global radiative forcing from CFCs has declined since its peak. CFCs have atmospheric lifetimes of decades to centuries, while those of HCFCs are generally less than 20 years.

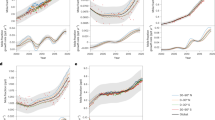

In this Brief Communication, we show that the global direct radiative forcing and equivalent effective chlorine (EECl) of HCFCs have fallen between 2021 and 2023 (EECl represents the globally averaged chlorine content of ODSs in the troposphere). Using measurements from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) and the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA), the global direct radiative forcing from HCFCs peaked in 2021 at 61.75 ± 0.056 mW m−2 (all errors are 1 standard deviation due only to measurement errors and global averaging; Methods) and EECl peaked at 321.69 ± 0.27 ppt. In 2022, these values dropped to 61.67 ± 0.058 mW m−2 and 321.35 ± 0.28 ppt and in 2023 to 61.28 ± 0.069 mW m−2 and 319.33 ± 0.33 ppt. Given the errors, there is an 84% (81%) probability that the global radiative forcing (EECl) peak occurred in 2021 not 2022. These trends are shown in Fig. 1 and are the averaged AGAGE and NOAA measurements. The results from each network, treated independently, also confirm this peak. The fall was most rapid in the northern hemisphere, reflecting emission changes. In the northern hemisphere, radiative forcing (EECl) has fallen from 63.76 ± 0.16 mW m−2 (332.59 ± 0.74 ppt) in 2021 to 63.11 ± 0.19 mW m−2 (329.35 ± 0.91 ppt) in 2023. The drop in radiative forcing and EECl was largely due to the atmospheric decline of the most abundant HCFC, HCFC-22, from its peak abundance of 248.96 ± 0.26 ppt in 2021 to 247.33 ± 0.32 ppt in 2023 (Extended Data Fig. 1). The second most abundant HCFC, HCFC-141b, showed a small decrease for the first time from 24.63 ± 0.026 ppt in 2022 to 24.51 ± 0.037 ppt in 2023. There was a renewed increase in emissions of HCFC-141b in 2017–2021, which was most probably due to HCFC-141b being released into the atmosphere when appliance foams containing HCFC-141b reached the end of their life10 and potentially from its release during its use as a feedstock in the production of polymers11. The third most abundant HCFC, HCFC-142b, has fallen monotonically from 22.35 ± 0.017 ppt since 2017. The timing of the apparent peak in HCFC radiative forcing and EECl is 5 years earlier than a previously projected maximum radiative forcing of 62.90 mW m−2 and EECl of 328.08 ppt in 2026 (based on HCFC-22, HCFC-141b and HCFC-142b only)11.

a, The total direct global radiative forcing from HCFCs until 2023 and the projected radiative forcing until 2100. b, The EECl from HCFCs until 2023 and the projected EECl until 2100. The projection is for HCFC-22, HCFC-141b and HCFC-142b only (Methods), which are shown to the right of the white dotted line. The category ‘other HCFCs’ contains HCFC-124, HCFC-132b, HCFC-31 and HCFC-133a. We assume all other HCFCs have a negligible contribution to radiative forcing and EECl. Thin black lines indicate the return to 1980 levels.

Several minor HCFCs, with abundances less than 1 ppt, show a mixed picture, with HCFC-124 abundances declining, but HCFC-31, HCFC-133a and HCFC-132b abundances either being relatively constant or increasing in recent years12. Emissions of these minor HCFCs are probably dominated by their leakage during the production of other chemicals12. Production of HCFCs and other ODSs during the manufacture of other chemicals—either as feedstocks, intermediates or by-products—is not controlled under the Montreal Protocol, since it had been assumed that emissions from such processes were negligible; yet recent studies suggest that ODS emissions from these sources are not9,13.

The radiative forcing from HCFCs in 2021 is around a fifth of that from CFCs at their peak of 286 mW m−2 in 2000 (ref. 6), an additional success of the Montreal Protocol. The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol initiated controls on production and consumption of HFCs, which have widely replaced HCFCs for many applications. Additional commitments have been made to reduce emissions of HFCs under the Paris Agreement and the Global Cooling Pledge14. However, despite the controls, the radiative forcing due to HFCs is still increasing.

The reduction in total radiative forcing of HCFCs further demonstrates the benefits of the Montreal Protocol in minimizing global temperature increases and its success in reducing stratospheric ozone loss. However, it remains to be seen how rapidly total radiative forcing and EECl from HCFCs will fall. Our projections show that HCFCs will return to their 1980 values in 2082 for radiative forcing and in 2087 for EECl (these projections are based on the dominant three HCFCs; Methods). Production and consumption of HCFCs are being phased out under the Montreal Protocol, whereas their emissions to the atmosphere are not directly controlled. Therefore, leakage of HCFCs from appliances and foams will continue over the product lifetimes, contributing to radiative forcing and EECl, as shown in Fig. 1, unless efforts are made to reclaim the HCFCs before their eventual release to the atmosphere. Furthermore, the use of HCFCs as feedstock for the production of other chemicals, such as HFCs and polytetrafluoroethylene15,16, is expected to continue long into the future. HCFC-22 is the dominant HCFC used as feedstock, and emissions from such use accounted for 4–8% (14.3–28.5 Gg yr−1) of total HCFC-22 emissions in 2019 (ref. 11). Global emissions of HCFC-22 have fallen since 2010 and are the main driver behind the decrease in radiative forcing and EECl from HCFCs. If the future global abundance of HCFC-22 is to exceed that observed in 2021, emissions of HCFC-22 from feedstock usage must be large enough for total emissions to return to or exceed their 2021 levels (around 347 Gg yr−1) for a sustained period. Avoidance of additional radiative forcing and EECl from emissions of HCFCs during the manufacture of other chemicals would require changes to the Protocol. Controls on by-product emissions of HFC-23 during HCFC and HFC production have recently been implemented as part of the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, where the emissions of HFC-23 should be avoided to the extent practicable. Any future increase in radiative forcing and EECl of HCFCs would be contrary to the goals of the Montreal Protocol.

Our latest observations show that the total radiative forcing and EECl from HCFCs has fallen for the first time. This demonstrates the success of the controls of the Montreal Protocol in mitigating loss of stratospheric ozone and its additional benefits to the climate. In the absence of future increases in ODS production, it was anticipated that Antarctic ozone recovery will occur later this century. The observed reduction in HCFC abundance is sooner than anticipated and may move forward this date for recovery when considered in future projections. The total radiative impact of all synthetic halogenated gases is still increasing, due to increasing abundances of HFCs and other fluorinated greenhouse gases. Adherence to the Kigali Amendment, Paris Agreement and Global Cooling Pledge should ensure that, in time, the radiative impact of HFCs will follow a similar decline to that observed for HCFCs.

Methods

Measurements of HCFCs

The compounds considered here in calculating total global HCFC radiative forcing and EECl are HCFC-22, HCFC-141b, HCFC-142b, HCFC-124, HCFC-132b, HCFC-133a and HCFC-31. Other HCFCs that have been detected in the atmosphere are not included on the basis of their low abundance, short lifetimes and radiative efficiencies3 and will have a negligible impact on the reported quantities. Atmospheric measurements are from the AGAGE and NOAA networks through 2023.

A general overview of the measurement approach in the AGAGE network is outlined in ref. 17, and in more detail for HCFC-22, HCFC-142b, HCFC-124 and HCFC-141b in ref. 18. The measurements of HCFC-132b, HCFC-31 and HCFC-133a are outlined in ref. 12, which were updated until 2023 for this work. The measurement record in this work began in 1978 for HCFC-22, 1973 for HCFC-141b, 1978 for HCFC-142b and 2003 for HCFC-124. The AGAGE measurement record consists of results from the analysis of archived air collected periodically at Trinidad Head and Kennaook/Cape Grim (Extended Data Table 1) before 1998 for HCFC-22 and HCFC-141b and before 1994 for HCFC-142b; high-frequency measurements at multiple sites were added in more recent years (Extended Data Table 1). Measurements of HCFC-133a began in 1973 and are taken from previous literature12 until 2014, after which measurements from the AGAGE network were used. The same applies to HCFC-132b, whose record started in 1978. Measurements of HCFC-31 were updated from a previous record12 through August 2023. All other AGAGE data used were through 2023. Details on the measurement locations of HCFC-132b and HCFC-133a before 2014, and locations of measurements of HCFC-31, are given in ref. 12. The NOAA measurements of HCFC-22, HCFC-142b and HCFC-141b from a globally distributed sampling network are outlined in ref. 19 and updated until 2023 in this work. The sampling locations are shown in Extended Data Table 1. NOAA measurements of HCFC-22 used in this work began in 1991, for HCFC-141b in 1990 and for HCFC-142b in 1992.

Calculation of global mean quantities and their uncertainties

The global mean well-mixed background surface mole fractions are estimated using background surface measurements from each network, which are assimilated into the AGAGE 12-box model20,21, using an approach described previously10,18. Measurements of HCFC-133a and HCFC-132b through 2014, and HCFC-31, were reanalysed using the same approach.

A single estimate of abundance is made using the mean of the global averages of the two global networks, at times when measurements from both networks are available. The global total radiative forcing of HCFCs in 2023 is 61.78, 61.71 or 61.75 mW m−2 using measurements from AGAGE, NOAA or both networks, where measurements from both networks are used for Fig. 1. Global total EECl in 2023 is 321.81, 321.56 or 321.69 ppt using AGAGE, NOAA or both measurement networks. All global mean mole fractions used to derive the global totals from all measurements are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1, for each network independently. Extended Data Fig. 1 shows that abundances measured by AGAGE and NOAA agree very well, albeit with some small differences for HCFC-142b, but very similar trends. The agreement in trends, over absolute values, is of particular importance in this work given that it is the timing of increases and decreases abundances that is of focus.

For clarity, uncertainties in the main text are reported assuming no error in the radiative efficiency (see next paragraph) and no error from the measurement calibration scales used by either network. Errors in calibration scales are additive or multiplicative adjustments to the measurements, and therefore, trends remain robust even in the presence of calibration differences. In the main text, the uncertainty is given as the 1 standard deviation uncertainty of the mean derived value from both networks (that have independent calibration), assuming that the measurement errors are fully correlated due to the similar approach to the measurements and derived quantities. This can be thought of as the random error in the reported quantities. The calibration error is included in the supplement for each network and gas alongside the respective mole fractions. When including the calibration error, the uncertainty in the maximum radiative forcing from HCFCs is 61.75 ± 0.55 mW m−2 and the EECl is 321.69 ± 2.71 ppt.

The total effective direct radiative forcing is calculated using the annual global mean surface mole fraction output from the 12-box model and the recommended adjusted effective radiative efficiency for each gas3. Uncertainties in the radiative efficiencies are ~14% for each HCFC with an atmospheric lifetime ⪆5 years and ~24% for those with lifetimes ⪅5 years22, and are added in quadrature to calculate the total uncertainty due to radiative efficiencies for HCFCs. These uncertainties are not included in the radiative forcing quoted in the main text, and therefore should be added in quadrature to other sources of uncertainty for an absolute uncertainty on radiative forcing. The peak HCFC radiative forcing including both calibration error and uncertainties in the radiative efficiencies is 61.75 ± 7.93 mW m−2. The uncertainty in the radiative efficiency does not impact the timing of the peak as this uncertainty will introduce a systematic rather than random error to the radiative forcing.

Projections of HCFCs

Projections of HCFCs are made following the approach in ref. 11, using the baseline scenario, but with updated production data of HCFCs reported to the United Nations Environment Programme through 2022 and updated surface mixing ratios for HCFC-22, HCFC-141b and HCFC-142b through 2023. The lifecycle and emissions of the other HCFCs are currently not sufficiently understood to make projections. We assume no production in non-Article 5 (developed) countries since 2020, following the Montreal Protocol phase-out schedule, and therefore all production is assumed to come from Article 5 (developing) countries. Bank estimates through 2023 were updated using the previously reported approach, with revised annual bank release fractions calculated. Because reported production over 2020–2022 was lower than that assumed in ref. 11 for 2023 and 2024, projected production in these two years is assumed to remain at the 2022 reported levels. The projected production in 2023 and 2024 is below what is required under the Montreal Protocol but still above the phase-down requirements starting in 2025. After 2024, projected production is taken from ref. 11. From 2025 to 2029, production is scaled proportionally, so that the total ozone depletion-weighted production was equal to 30% of the Protocol’s baseline HCFC production in Article 5 countries. Production is then scaled to reach 2.3% of the baseline production in 2030–2039. This assumes that the full allocation under the Montreal Protocol is not used, in line with the latest available production data. The approach taken in ref. 11 and here assumes that all of an ODS that is produced goes directly into the bank and then is released in the future with a constant bank release rate. This rate is assumed to be the bank release rate averaged over the final 7 years when emissions estimates are available. For these reasons the scenarios are probably high-end estimates of the future projections of these HCFCs, providing even more robustness to the main conclusion presented here.

Data availability

Monthly mean data used as input to derive the global mean quantities, projected mole fractions for HCFC-22, HCFC-141b and HCFC-142b, and estimated global mole fractions are available from ref. 23. AGAGE data, used to derive the monthly mean values, are available at http://agage.mit.edu/data/agage-data (last accessed 20 February 2024) and https://data.ess-dive.lbl.gov/ (current dataset ref. 24). The most recent NOAA atmospheric observations are available at https://gml.noaa.gov/aftp/data/hats/hcfcs/ (last accessed 20 February 2024).

Code availability

The 12-box model and the method used to quantify global mean mole fractions are available via GitHub at https://github.com/mrghg/py12box (last accessed 05 March 2024) and https://github.com/mrghg/py12box_invert (last accessed 05 March 2024) and refs. 25,26.

References

Molina, M. J. & Rowland, F. S. Stratospheric sink for chlorofluoromethanes: chlorine atom-catalysed destruction of ozone. Nature 249, 810–812 (1974).

Hassler, B. & Young, P. J. Update on global ozone: past, present and future. in Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022 Chap. 3 (World Meteorological Organization, 2023).

Burkholder, J. B. & Øivind, H. Summary of abundances, lifetimes, ODPs, REs, GWPs, and GTPs. in Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022, Annex (World Meteorological Organization, 2023).

Newman, P. A. et al. What would have happened to the ozone layer if chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) had not been regulated? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 2113–2128 (2009).

Young, P. J. et al. The Montreal Protocol protects the terrestrial carbon sink. Nature 596, 384–388 (2021).

Laube, J. C. et al. Update on ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) and other gases of interest to the Montreal Protocol. in Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022 Chap. 1 (World Meteorological Organization, 2023).

Montzka, S. A. et al. An unexpected and persistent increase in global emissions of ozone-depleting CFC-11. Nature 557, 413–417 (2018).

Park, S. et al. A decline in emissions of CFC-11 and related chemicals from eastern China. Nature 590, 433–437 (2021).

Western, L. M. et al. Global increase of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons from 2010 to 2020. Nat. Geosci. 16, 309–313 (2023).

Western, L. M. et al. A renewed rise in global HCFC-141b emissions between 2017–2021. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 9601–9616 (2022).

Daniel, J. S. & Reimann, S. Scenarios and information for policymakers. in Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022 Chap. 7 (World Meteorological Organization, 2023).

Vollmer, M. K. et al. Unexpected nascent atmospheric emissions of three ozone-depleting hydrochlorofluorocarbons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2010914118 (2021).

Lickley, M. et al. Quantifying contributions of chlorofluorocarbon banks to emissions and impacts on the ozone layer and climate. Nat. Commun. 11, 1380 (2020).

Keeping Cool in an Increasingly Hotter World: UNEP Spotlight (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023).

Andersen, S. O. et al. Narrowing feedstock exemptions under the Montreal Protocol has multiple environmental benefits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2022668118 (2021).

Mühle, J. et al. Global emissions of perfluorocyclobutane (PFC-318, c-C4F8) resulting from the use of hydrochlorofluorocarbon-22 (HCFC-22) feedstock to produce polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and related fluorochemicals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 3371–3378 (2022).

Prinn, R. G. et al. History of chemically and radiatively important atmospheric gases from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE). Earth System Science Data 10, 985–1018 (2018).

Simmonds, P. G. et al. Changing trends and emissions of hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and their hydrofluorocarbon (HFCs) replacements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 4641–4655 (2017).

Montzka, S. A. et al. Recent trends in global emissions of hydrochlorofluorocarbons and hydrofluorocarbons: reflecting on the 2007 adjustments to the Montreal Protocol. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 4439–4449 (2015).

Cunnold, D. M. et al. The Atmospheric Lifetime Experiment: 3. lifetime methodology and application to three years of CFCl3 data. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 88, 8379–8400 (1983).

Rigby, M. et al. Re-evaluation of the lifetimes of the major CFCs and CH3CCl3 using atmospheric trends. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2691–2702 (2013).

Hodnebrog, Ø. et al. Updated global warming potentials and radiative efficiencies of halocarbons and other weak atmospheric absorbers. Rev. Geophys. 58, e2019RG000691 (2020).

Western, L. M. Supplementary data to ‘Radiative forcing and equivalent effective chlorine due to hydrochlorofluorocarbons peaked in 2021’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.10782689 (2024).

Prinn, R. et al. The dataset of in-situ measurements of chemically and radiatively important atmospheric gases from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gas Experiment (AGAGE) and affiliated stations (2023R2). ESS-DIVE https://doi.org/10.15485/2216951 (2023).

Rigby, M. & Western, L. mrghg/py12box: v0.2.1. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.6857447 (2022).

Rigby, M. & Western, L. mrghg/py12box_invert: v0.0.2. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.6857794 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to those making measurements for their dedication to producing high-quality atmospheric trace gas measurements foremost the station manager and station operators. The AGAGE Medusa GC–MS system development, calibrations and measurements at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla and Trinidad Head, CA, USA; Mace Head, Ireland; Ragged Point, Barbados; Cape Matatula, American Samoa; and Kennaook/Cape Grim, Australia were supported by the NASA Upper Atmospheric Research Program in the United States with grants NNX07AE89G, NNX16AC98G and 80NSSC21K1369 to MIT and NNX07AF09G, NNX07AE87G, NNX16AC96G, NNX16AC97G, 80NSSC21K1210 and 80NSSC21K1201 to SIO (and earlier grants). The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) in the United Kingdom supported the University of Bristol for operations at Mace Head, Ireland (contracts 1028/06/2015, 1537/06/2018 and 5488/11/2021) and through the NASA award to MIT with the subaward to University of Bristol for Mace Head and Barbados (80NSSC21K1369). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the United States supported the University of Bristol for operations at Ragged Point, Barbados (contract 1305M319CNRMJ0028) and operations at Cape Matatula, American Samoa. In Australia, the Kennaook/Cape Grim operations were supported by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), the Bureau of Meteorology (Australia), the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (Australia), Refrigerant Reclaim Australia and through the NASA award to MIT with subaward to CSIRO for Cape Grim (80NSSC21K1369). Measurements at Jungfraujoch are supported by the Swiss National Programs HALCLIM (Swiss Federal Office for the Environment, FOEN), by the International Foundation High Altitude Research Stations Jungfraujoch and Gornergrat (HFSJG), and by the European infrastructure projects ICOS and ACTRIS. NOAA measurements were supported in part through the NOAA Cooperative Agreement with CIRES (NA17OAR4320101). This work received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Słodowska–Curie grant agreement no. 101030750 (L.M.W.). M.R. received funding from the Natural Environment Research Council Highlight Topic Investigating HALocabon impacts on the global Environment (InHALE, NE/X00452X/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M.W. conceived the project and led the analysis. J.S.D. created the projections of HCFCs. M.K.V., S.C., M.C., P.J.F., A.L.G., C.M.H., P.B.K., J.M., S.O.’D., K.M.S., S.R., I.V., D.Y., R.F.W. and S.A.M. made and provided measurement data, including its quality control and analysis. B.H., C.M.H. and P.K.S. provided calibration, quality control and analysis tools to make the measurements. L.M.W. and M.R. produced the globally averaged mole fractions using the 12-box model. R.G.P. provided oversight and management of the AGAGE network. L.M.W. led the writing of the article, with contributions from J.S.D., M.K.V., P.B.K., J.M., S.R., M.R., R.G.P. and S.A.M. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Nicole Miranda, Gunnar Myhre and Hua Zhang for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

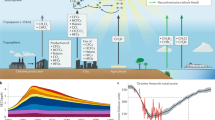

Extended Data Fig. 1 Global mean abundances of HCFCs.

Global mean mole fractions from each network and other available measurements to derive the reported quantities in the main text. Measurements other than those made by the AGAGE and NOAA networks are reported in Vollmer et al.12 and are updated here.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Western, L.M., Daniel, J.S., Vollmer, M.K. et al. A decrease in radiative forcing and equivalent effective chlorine from hydrochlorofluorocarbons. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 805–807 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02038-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02038-7