Phasing out coal requires expanding the notion of a ‘just transition’ and a roadmap that specifies the sequence of coal plant retirement, the appropriate policy instruments as well as ways to include key stakeholders in the process.

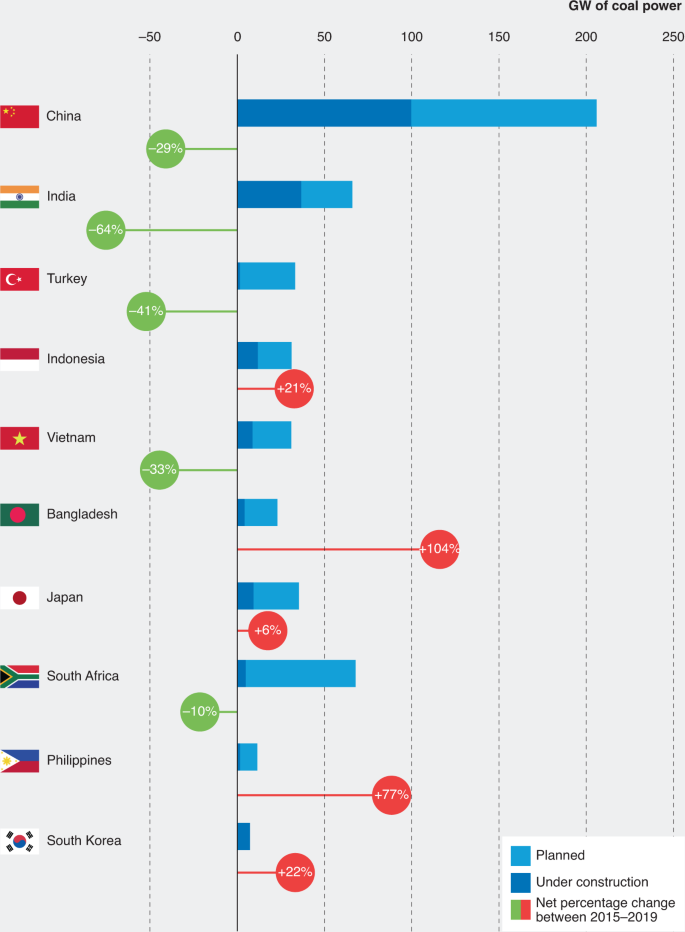

Despite decades of knowledge about its contribution to climate change, coal combustion still accounts for 40% of global CO2 emissions from energy use. The power sector must stop using coal without carbon capture and storage by approximately 2050 if the Paris Agreement climate goals are to be achieved1. This will not be easy. Globally, the coal mining industry alone employs about 8 million people and creates revenues of more than US$900 billion a year2. While growth in coal investments is slowing and COVID-19-induced electricity demand reductions have cut coal-fired electricity output in 2020, coal use is unlikely to decline substantially in the medium term. Reductions in the USA and Europe are offset by growth in China, India and other Asian countries3,4, thus locking in future demand (Fig. 1). African countries may follow next5.

Coal-fired power plants in the pipeline (planned, announced or under construction) as well as changes relative to 2015 (ref. 19). Percentage changes denote changes in the total pipeline between 2015–2019.

Still, the urgency of climate change action demands the world to reduce coal use without carbon capture and storage quickly, and cease it over coming decades6. Yet, focusing on the environmental and health related externalities7,8 of coal combustion will likely not be sufficient to phase out coal. Rather, it will be crucial that the coal phase out is seen as fair and that the process corresponds to political realities. Policymakers need to understand in more detail who will be affected by a transition away from coal, how these societal groups can be effectively compensated and how powerful vested interests can be counterbalanced.

Expanding the notion of just transition

It is understood that a coal phase-out can only succeed if it takes into account social objectives and priorities. The necessity of a ‘just transition’ is widely acknowledged (Box 1). Such dialogue typically emphasizes employment creation but often fails to include considerations related to (i) regional economic development, (ii) effects of higher energy prices for consumers and energy-intensive industries and (iii) how just transition dynamics may cascade beyond individual countries9. Hence, what is needed is a just and feasible transition providing decent work and quality jobs as well as regional economic futures while at the same time limiting adverse impacts on consumers and energy-intensive industries.

Regional economic futures

While the environmental and health effects of coal are well understood, policymakers in newly industrializing countries often highlight the importance of coal for industrial development in specific regions10. Planning for alternative regional economic futures to substitute for coal requires a clearer understanding of the upstream and downstream links of coal mining and coal-fired power generation to the broader economy. Such plans could include the provision of transport and communication infrastructure, investment in higher education to attract human capital and new business opportunities, as well as the relocation of government services.

Impacts on consumers and energy-intensive industries

Renewing energy supply systems can increase electricity system costs: for example, depreciated coal plants may produce electricity at lower costs than new alternative power generation assets. It is then a question of social equity to shield the poor from electricity price increases. This can be achieved by adjusting electricity tariffs, raising social spending or subsidizing energy efficiency, depending on the given institutional and political context.

Foregoing coal could also affect the competitiveness of industries such as steel, aluminium, chemicals and other important components of industrial strategy. This might raise the risk of ‘carbon leakage’; that is, the migration of energy-intensive industries to regions with laxer climate measures, thus undermining the benefits for the climate and making coal phase-outs politically more difficult. More fine-grained projections of leakage risks in different sectors under a wide range of scenarios are required to explore which policy instruments can effectively reduce leakage. Options include coordinated implementation of emission reductions among different countries, the free allocation of permits within emissions trading schemes, border carbon adjustments, carbon contracts for difference and mechanisms of technology transfer11.

Expanding the feasibility space for phasing out coal

The coal industry typically is a powerful stakeholder with vested interests in delaying coal phase-out. Strategies to overcome the influence of vested interests might include government payments for coal power plants that are being closed. In Germany, for example, the government agreed in early 2020 on a set of measures to phase out coal by 2038 with additional costs of €70–90 billion, including €4.35 billion to operators of (lignite) coal-fired power plants that, in turn, shut down their plants early; that is, before 2030. More cost-efficient alternatives that could be assessed include accelerated carbon pricing or industry-internal schemes whereby remaining power stations pay out plants that are retiring ahead of their end of economic life12. In addition, the interests of alternative energy producers can be leveraged to help build coalitions that create support for coal phase-out that partially offsets the opposition of those losing out13,14.

A phase-out roadmap in practice

A viable coal phase-out strategy will need to prevent new coal-fired power plants from being built. This prevents locking in long-lived assets and is usually politically easier to achieve than closing existing plants early. In many cases, expanding power supply through sources other than coal (that is, renewables or natural gas) is cost effective, even before considering the environmental and health costs of coal use. This will increasingly be the case as the cost of renewable energy technologies continues to fall. Nevertheless, there are factors that tend to favour continued investment in coal assets, including the security of supply in regions with abundant coal resources, the desire to protect jobs in the coal sector and in regional areas of coal production, dependence of public budgets on royalties from coal mining as well as political influence of owners of coal mines and power producers.

Coal phase-outs therefore require roadmaps based on a clear understanding of which plants are to be phased out when, which policies can be applied and how affected stakeholders can be included in the process.

Sequence phase-outs

The age profile of coal power plants differs greatly between countries. Industrialized countries typically built up a large part of their power infrastructure before 1990, whereas India, China and many other industrializing countries ramped up coal use in the last 15 to 30 years1 (economic logic suggests that relatively old, and typically less efficient, plants often found in developed countries should be decommissioned first). Other factors to consider are the public health impacts of associated air pollution and water use in densely populated areas. A realistic sequence of power plant closure will also need to take into account political and institutional constraints.

A nuanced understanding of the associated political barriers as well as feasible no-lose options can help to identify countries and regions where policy action in the near term is more likely than in.

Choosing the right instruments

Coal producers and consumers need to understand the real costs of coal, including local health damages and climate consequences for the climate. Removing any existing coal subsidies would be a step to creating a level playing field for clean energy sources to compete. Some jurisdictions may want to impose an additional carbon cost on coal plants to accelerate coal phase-out. To be socially equitable and politically acceptable, a carbon price could raise funds in support of affected workers, communities and consumers. It may be usefully embedded within a broader reform to the tax system geared to assist low-income households15.

In addition, central banks and financial regulators need to include the climate and financial risks associated with coal assets in the prudential management of banks, insurers and institutional investors16. Transparent disclosure of exposure to financial risks of climate policy could provide an important motivation for investors to reallocate assets away from coal17. Financial investors increasingly decline to invest in coal-based assets already, because they are seen as high risk18.

Stakeholder involvement and communication

Efforts to phase out coal will only succeed if stakeholders are involved early on in the decision process to ensure democratic legitimacy. This is particularly important during times in which populist parties increasingly depict climate change mitigation as a project undertaken by the political elite against the interests of the broader population, and where well-founded concerns about economic prosperity dominate public discourse.

Different forms of public deliberation, such as stakeholder dialogues, just transition commissions and citizen assemblies, reflect public opinion and could be apt to further agreement between different interests. This raises the question of how participants are selected, in which form and frequency discussions take place, how scientific knowledge is used as an input and how the results of public deliberation are used by policymakers. Policymakers could adapt their communication strategies on coal phase-out for different audiences that highlight the key benefits that align with individual concerns; for instance, emphasizing the importance of coal phase-out for climate change mitigation for one social group and the more localized benefits of reduced air pollution for others.

How to phase out coal

To achieve internationally agreed climate targets, the world will need to phase out coal rapidly and immediately. This may be politically even more difficult in the altered political and economic landscape after the coronavirus pandemic. Roadmaps for coal phase-out, smart use of a combination of policy instruments and effective integration of powerful stakeholders into the process are key to success.

References

Edenhofer, O., Steckel, J. C., Jakob, M. & Bertram, C. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 024019 (2018).

Global Coal Mining Industry - Market Research Report (IBISWorld, 2019); https://www.ibisworld.com/global/market-research-reports/global-coal-mining-industry/

Thurber, M. C. & Morse, R. K. in The Global Coal Market (eds Thurber, M. C. & Morse, R. K.) 3–34 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015).

Jewell, J., Vinichenko, V., Nacke, L. & Cherp, A. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 592–597 (2019).

Steckel, J. C., Hilaire, J., Jakob, M. & Edenhofer, O. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 83–88 (2020).

Luderer, G. et al. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 626–633 (2018).

Li, M., Zhang, D., Li, C.-T., Selin, N. E. & Karplus, V. J. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 084006 (2019).

Muller, N. Z., Mendelsohn, R. & Nordhaus, W. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 1649–1675 (2011).

Sovacool, B. K., Hook, A., Martiskainen, M. & Baker, L. Glob. Environ. Chang. 58, 101958 (2019).

Kalkuhl, M. et al. Nat. Energy 4, 897–900 (2019).

Jakob, M., Steckel, J. C. & Edenhofer, O. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 6, 297–318 (2014).

Jotzo, F. & Mazouz, S. B. E. J. Econ. Anal. 48, 71–81 (2015).

Kim, S. E., Urpelainen, J. & Yang, J. J. Public Policy 36, 251–275 (2016).

Hess, D. J. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 57, 101246 (2019).

Klenert, D. et al. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 669–677 (2018).

First Meeting of the Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) on January 24th in Paris. Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System (26 January 2018); https://www.ngfs.net/en/communique-de-presse/first-meeting-central-banks-and-supervisors-network-greening-financial-system-ngfs-january-24th-0

Guidelines on Reporting Climate-related Information (European Commission, 2019); https://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/policy/190618-climate-related-information-reporting-guidelines_en.pdf

The Investor Agenda. 2018 Global Investor Statement to Governments on Climate Change (COP24 Presidency Office, Ministry of the Environment, 2018).

Global Coal Plant Tracker (Global Energy Monitor, 2020).

Smith, S. Just Transition: A Report for the OECD (OECD Publishing, 2017); https://www.oecd.org/environment/cc/g20-climate/collapsecontents/Just-Transition-Centre-report-just-transition.pdf

Adoption of the Paris Agreement FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1 (UNFCCC, 2015).

Solidarity and Just Transition Silesia Declaration (COP24 Presidency Office, Ministry of the Environment, 2018); https://cop24.gov.pl/fileadmin/user_upload/Solidarity_and_Just_Transition_Silesia_Declaration_2_.pdf

Carley, S. & Konisky, D. M. Nat. Energy https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0641-6 (2020).

Jenkins, K. E. H., Sovacool, B. K., Błachowicz, A. & Lauer, A. Geoforum (in the press); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.05.012

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jakob, M., Steckel, J.C., Jotzo, F. et al. The future of coal in a carbon-constrained climate. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 704–707 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0866-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0866-1

This article is cited by

-

Limited impact of hydrogen co-firing on prolonging fossil-based power generation under low emissions scenarios

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Quantifying the spatiotemporal patterns and environmental impacts of surface coal mining in the Xilingol Steppe, Inner Mongolia

Regional Environmental Change (2024)

-

Insight into Energy Production and Consumption, Carbon Emissions and Agricultural Residues Resources Available for Energy and Environmental Benefits in China

Waste and Biomass Valorization (2024)

-

Coal-exit alliance must confront freeriding sectors to propel Paris-aligned momentum

Nature Climate Change (2023)

-

Co-firing plants with retrofitted carbon capture and storage for power-sector emissions mitigation

Nature Climate Change (2023)