Abstract

App-based interventions have the potential to enhance access to and quality of care for patients with schizophrenia. However, less is known about the current state of schizophrenia apps in research and how those translate to publicly available apps. This study, therefore, aimed to review schizophrenia apps offered on marketplaces and research literature with a focus on accessibility and availability. A search of recent reviews, gray literature, PubMed, and Google Scholar was conducted in August 2022. A search of the U.S. Apple App Store and Google Play App Store was conducted in July 2022. All eligible studies and apps were systematically screened/reviewed. The academic research search produced 264 results; 60 eligible studies were identified. 51.7% of research apps were built on psychosis-specific platforms and 48.3% of research apps were built on non-specific platforms. 83.3% of research apps offered monitoring functionalities. Only nine apps, two designed on psychosis-specific platforms and seven on non-specific platforms were easily accessible. The search of app marketplaces uncovered 537 apps; only six eligible marketplace apps were identified. 83.3% of marketplace apps only offered psychoeducation. All marketplace apps lacked frequent updates with the average time since last update 1121 days. There are few clinically relevant apps accessible to patients on the commercial marketplaces. While research efforts are expanding, many research apps are unavailable today. Better translation of apps from research to the marketplace and a focus on sustainable interventions are important targets for the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing access to care for people with schizophrenia remains a global health priority1. Given their scalable potential, digital mental health and especially smartphone-based solutions have become a topic of great interest2. In the last decade, research on smartphone apps for people with schizophrenia has expanded, with results suggesting uses cases around early diagnosis, real-time monitoring, psychoeducation, relapse prevention, and even therapeutic interventions3,4,5. But to what degree has this research translated into digital tools that patients today can access and utilize? This paper thus aims to review both the research and commercial marketplaces for apps for people with schizophrenia and explore their availability and accessibility.

Smartphone apps represent an important solution to increasing access to care for people with schizophrenia. A preponderance of data suggests that not only do people with schizophrenia own smartphones at high rates but that they also are interested in using them as part of their recovery5,6,7,8,9,10. Despite often raised questions by the public regarding whether smartphone-based monitoring or interventions may make people with schizophrenia more paranoid, there remains scant data to support this unfounded claim11. Rather, people with schizophrenia have themselves been at the forefront of developing and researching new advances in the uses of smartphones for their condition12,13.

The driving force behind the interest in smartphones centers on increased access to care. The simple reality of the lack of a mental health workforce able to deliver care to people with serious mental illness was clear before COVID-19, and now is even more apparent14. Given the enormous mental health gap in services, impacting all countries in the world, digital solutions that are scalable represent a critical target for increasing access to care15. As the unmet need for care for people with schizophrenia is at the higher end of the spectrum, the concomitant interest in smartphone apps for this condition is clear. Apps have been proposed as tools to help with screening and monitoring of schizophrenia as well as tools to offer on-demand as well as just-in-time adaptive interventions16,17; and an active area of research for the last ten years.

Beyond access, interest in these apps is also fueled by the potential of smartphone apps to deliver more holistic and eclectic treatments beyond those readily accessible today. For example, smartphone apps can facilitate cognitive remediation treatments, peer support, cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis, and other services that may be challenging for patients to find today even in well-resourced countries5.

However, despite this potential, it is also clear from evidence across all of digital health that smartphone apps alone are not a panacea. Concerns around privacy, effectiveness, engagement, and clinical integration are now well-recognized barriers for all health-related apps, including mental health apps18. Even in 2022, mental health app privacy concerns continue to make national news19 and there is rising awareness for high quality studies that assess the impact of these apps against appropriate control conditions20,21. While practical experience suggests that apps for people with schizophrenia have not yet transformed care in 2022 and that there is no well-defined or practical distinction between clinician-prescribed apps and self-prescribed apps related to schizophrenia, little is actually known about the current state of the field or the availability of apps for practical patient use.

To understand the current state of apps for schizophrenia, this review aims to catalog these apps developed in the research space based on platforms and assess their current availability. In parallel, this review also aims to investigate the quality of apps currently offered on the Apple and Android marketplaces and assess any overlap or differences in features between the research apps. Towards understanding factors that may impact availability, this review focuses on apps as platforms rather than the clinical results of any one study.

Methods

Research articles search and a literature review

To analyze the current research on smartphone apps for individuals with psychosis, we searched recent reviews22,23, the gray literature, and standard academic databases including PubMed and Google Scholar. This intentionally surface-level search strategy of the academic literature was intentionally employed as a primary purpose of this dual review (which also searched app stores, see below) was to assess and compare the apps used in the most easily-identified research studies, to those available on publicly-accessible app marketplaces.

A search of PubMed and Google Scholar was performed on August 17, 2022, using the following search algorithm: (“smartphone*“ or “mobile phone*“ or “cell phone”)) AND (“app” or “apps” or “application” or “applications”)) AND (“schizophrenia” or “schizo” or “psychosis” or “psychotic”). However, a primary purpose of the review was to gain an assessment of the extent to which apps in readily-accessed research studies are aligned with those apps widely available on the marketplace, and there is no reason to believe that any missed studies more difficult to identify would significantly impact our data collection.

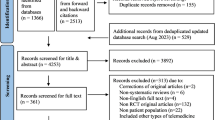

A total of 309 articles were revealed. After removing duplicates, a total of 264 articles remained.

Two authors (SK and DJ) screened each title/abstract for eligibility using the Covidence systematic review management tool24. Articles were excluded if they (1) delivered an intervention that is not mobile app-based (2) were unrelated to psychosis.

A total of 166 articles were reviewed in full text by 3 authors (SK, DJ, and JT) using the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: articles were excluded if they (1) utilized the same research app as other articles (2) were review articles (3) were non-specific to psychosis (4) were commentary or perspective articles (5) were conference abstracts (6) used the apps not intended for patients’ use, (7) were primarily focused on supporting different condition(s) such as smoking, or (8) were primarily focused on digital antipsychotic medication with the smartphone app only supporting the digital medicine. Consequently, a total of 60 research apps were included (Fig. 1). In this article, the term “research apps” will be used solely when referring to the mobile apps utilized by the academic article.

Public app marketplace mobile application search and an app audit

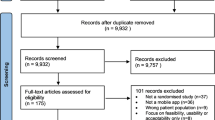

To analyze the current marketplace for psychosis apps, a search of the Apple App Store and Google Play App Store was conducted on July 24, 2022. There were no inclusion criteria for the commercial mobile application search since the aim of this study was to determine the most accessible and easily obtainable psychosis apps for a layperson. The terms “Schizophrenia” and “Psychosis” were entered. A total of 675 apps returned, which was reduced to 537 apps after duplicates across Apple and Android were eliminated. In the first phase of screening, returned apps were excluded if they (1) were not available in English (2) developed to include contents unrelated to mental health (eg dating apps) (3) were non-specific to schizophrenia or psychosis (4) claimed to primarily support different condition(s) (5) intended for test preparation (6) intended for non-patient use, and (7) cost more than $10.00 to download; this price limit was set on the premise that an app should be economically accessible and determined based on our team’s clinical experience and patient interactions.

Subsequently, a total of 512 apps were excluded. Two authors (SK and JT) downloaded and used the remaining 25 apps and reviewed each app for approximately 30 min. These apps were then further screened and excluded if they (1) contained outdated information as determined by a patient advisory panel (2) were non-functional (3) required access code, and (4) contained potentially dangerous or stigmatizing information as determined by a patient advisory panel. Outdated information included references and diagnosis excluded from the DSM-5. Potentially dangerous or stigmatizing information included home remedy recommendations without a proper side effects warning and a phrase that perpetuates negative labeling and perception. Subsequently, a total of six marketplace apps were included. The term “marketplace apps” will be utilized exclusively when referring to the psychosis mobile apps returned on the public app marketplace.

Therapeutic, monitoring, and psychoeducation (TMP) classification

There is no established nosology for the categorization of the main features or functionalities of research apps and marketplace apps. Thus, we opted to categorize these features or functionalities broadly into three categories: therapeutic, monitoring, and psychoeducation. For ‘therapeutic’ we counted any features that aim to improve symptoms, behavior or cognitive functioning, such as psychotherapy, skills training, peer support, and tailored daily activities. For “monitoring” we counted any features that help patients to track symptoms, treatment progress, or medications. For ‘psychoeducation’, we counted any features that offered reference or didactic information. Using this nosology, it is possible for the same app to offer therapeutic, monitoring, and psychoeducation functionalities.

Specific platform and non-specific platform

We further classified apps as built or running on specific vs non-specific platforms. A specific platform would be a custom app designed to run only that program. For example, an app built on specific platform would only provide psychoeducation regarding schizophrenia. A non-specific app may be a broad survey platform customized with relevant clinical content or an app platform customized to support specific content. For example, a non-specific app could be a survey-administering app that brings up different question sets based on a set-specific code. A researcher may create a set of questions relevant to schizophrenia patients and administer those questions using a non-specific app.

Data analysis process

A total of 60 research articles and their respective research apps were analyzed, and the data extracted including availability on the public app marketplace, access code requirement, supporting study authors and year, research app example features, TMP framework categorization, and specific vs non-specific platform. All research apps available for download were assessed to evaluate accessibility and categorized as restricted access (requires access code) or full access (does not require an access code).

A total of six marketplace apps were analyzed. Data analyzed included the date of last update, app descriptions, and the TMP framework categorization. The six marketplace apps were also rated based on the M-health Index and Navigation Database (MIND) derived from the American Psychiatric Association’s app evaluation framework25,26. MIND is the largest public database that allows any users to make an informed decision in choosing a mental health app. The rating included 105 objective questions pertaining to app origin, functionality, and accessibility; privacy and security; evidence and clinical foundations; features and engagement; interoperability and data sharing27.

Statistical analysis

The download availabilities of specific and non-specific research apps were compared using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 537 unique marketplace apps were identified on the United States Apple App Store and Google Play App Store when the terms “Schizophrenia” and “Psychosis” were searched. As shown in Fig. 2, 256 of 537 apps (47.7%) were not related to psychosis, and 32 of 537 apps (6.0%) were not developed to be used by individuals with psychosis. There were two apps (0.4%) that specifically stated they supported psychosis in addition to two or more different conditions, including eating disorder, PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, plus 27 other conditions, and 194 apps (36.1%) that claimed to support mental health wellness or provide information about mental health. Only 25 apps (4.7%) claimed to primarily support psychosis. However, of the 25 apps, one app was non-functional, seven were inaccessible without an access code, three apps contained outdated information such as reference to non-current diagnosis like Disorganized, Catatonic and Undifferentiated schizophrenia which have been removed from the DSM-5 for over five years. Eight apps contained stigmatizing or dangerous information such as telling users to “remember that it’s [schizophrenia] all in your head” or providing herbal supplement advice without discussing potentially dangerous medication interactions. Outdated information included references and diagnoses that had been excluded from the DSM-5, and dangerous information included a list of medications that can cause harmful drug interactions with antipsychotics. The accessibility to obtaining an access code was limited as users had to either (1) contact the app developer (2) contact the research group (3) partake in the research study or (4) be a patient at a specific clinic. Thus, a total of six easily accessible, appropriate, and psychosis-specific marketplace apps (1.1%) were evaluated using the MIND framework (Fig. 2).

Marketplace App

Of the six easily accessible, appropriate, and psychosis-specific marketplace apps, five apps solely presented psychoeducation (83.3%). Only one app, which was last updated 1587 days ago (4.34 years ago), offered therapeutic and monitoring functionalities without providing psychoeducation. All six apps were not updated frequently with the average time since last updated being 1121 days (3.07 years ago)—well exceeding the 180 days update metric adopted by the American Psychiatric Association, which prompts a concern for an app quality and safety28 (Table 1).

All six of these apps were free to download with one offering in-app purchases (16.7%) and five totally free (83.3%). One of the six apps was available on the Apple App Store, and all six apps were available on the Google Play App Store. Of the six apps, four apps had a privacy policy and only one app allowed users to delete data. Moreover, only one app allowed users to opt-out of data collection, and none of the apps claimed to meet Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, 1996 (HIPPA) – established to protect an individual’s protected health information29. Only one app included a published supporting study examining the app’s feasibility30.

Research App Feature

Of the 60 unique academic articles on smartphone apps for psychosis, 31 articles utilized apps designed with a psychosis-specific platform, and 29 articles used apps built on a non-specific platform to deliver psychosis-specific features. 50 of the 60 research apps provided symptom monitoring features while 30 research apps exclusively offered monitoring features, 14 research apps offered therapeutic and monitoring features, 3 research aps offered monitoring and psychoeducation features, and 3 research apps offered therapeutic, monitoring, and psychoeducation features, see Tables 2, 3. Although nine research apps included psychoeducation in addition to monitoring or therapeutic features, no research app solely provided psychoeducation (Tables 2, 3).

Research app accessibility

Regarding research app accessibility, 31 of the 60 research apps were not available on the public app marketplace. The remaining 29 research apps were available to be downloaded for free; however, 20 of the 29 research apps required an access code or special credential to access the app features. Thus, only nine research apps were available and easily accessible on the public app marketplace.

Research apps with psychosis-specific platform and non-specific platform differed significantly in their download availability on the public app marketplace (χ2 = 4.241, p = 0.039), with 64.5% of psychosis-specific platform apps and 37.9% of non-specific platform apps unavailable to be downloaded. Subsequently, research apps with non-specific platform had significantly higher download availability on the public app marketplace compared to that of research apps with psychosis-specific platform. However, both research apps with psychosis-specific platform and non-specific platform had limited accessibility with 29.0% and 37.9% of the apps requiring an access code, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

Study results suggest that while many academic apps have been developed to support people with schizophrenia, very few suitable apps are actually available for use today. The situation is related to the commercial marketplaces where hundreds of apps are returned in searches but there are less than ten that are accessible and clinically relevant. Despite impressive research efforts, people with schizophrenia are today able to access a paucity of apps. A focus on translating research efforts into accessible apps should become the priority for the field.

We identified sixty unique apps used in schizophrenia research. Of these 60 apps, 31 (51.7%) were not available at all meaning that it is challenging to replicate or expand on their results. This result is perhaps not surprising given the challenges and costs associated with maintaining apps. For example, Krzystanek, a developer of MONEO app included in the results31,32, explains “the investor who wanted to commercialize it [the MONEO app] was not up to the task, so the project was suspended.”33 However, our results do suggest one potential solution as we found that apps developed on non-specific platforms were significantly more available today than those created on customized app platforms (χ2 = 4.241, p = 0.039). While a customized app offers clear advantages, using a broader platform may offer a more rapid and sustainable approach, especially for early phase work.

While there are many reasons a research app may not be available for easy public use, our result that 20 (33.3%) were also not accessible as they required an access code is notable given the goal of most apps is to increase access to care. While our results cannot directly support why, it is likely that these apps themselves are necessary to use in concert with a care program and not as standalone self-help tools. Using apps to augment care can certainly help increase access to care, but raises the need for concomitant training, workforce, implementation, and clinical infrastructure to support scalability. In reviewing the relevant literature, we found such documentation was often lacking although it represents an important target for new and ongoing app efforts.

Of the 60 research apps, only nine (15.0%) research apps were available to download and directly use. However, these results must be interpreted with caution as only two of these nine apps was created on a schizophrenia specific platform and the other seven on non-specific app platforms. Examples of non-specific platforms include WeChat, MovisensXS, and mindLAMP (developed by the authors) meaning that a patient or clinician would need to customize or add content to the platform for it to be ready for clinical use. This may often involve a licensing fee depending on the app or at least some degree of technical knowledge, reflecting a further barrier to access.

While there is room to improve accessibility of research apps, our results suggest this work is necessary as the current marketplace offerings are concerning. After an exhaustive search of apps on the Apple App Store and Google Play App Store, we found only 25 psychosis-specific marketplace apps from the 537 our search revealed. Even though there exist other curated third-party health app marketplaces (e.g., Psyberguide34) that provide information regarding app availability, there is no reason to believe that any missed marketplace apps would change our results. Of these 25 apps, only six were deemed clinically appropriate with the other 19 offering inaccurate, outdated, stigmatizing, or inappropriate content. For example, one app tells users to “remember that it’s [schizophrenia] all in your head.”35 Two apps recommend “St John’s Wort [which] works as an antidepressant in patients with schizophrenia disorder”36,37 as a part of the home remedies without clear warnings of dangerous medication interactions38. Three apps offered psychoeducation about “Disorganized, Catatonic and Undifferentiated schizophrenia”39,40,41 which have been removed from the DSM-5 for over five years42.

Considering the six (1.1% of 537 marketplace app) that were deemed clinically appropriate, five apps (only available on Google Play App Store) solely provided information/psychoeducation, and only one app (available on both Apple App Store and Google Play App Store) included therapeutic and monitoring features. The paucity of apps with therapeutic features may be that apps with therapeutic or diagnostic features are subject to Food and Drug Administration’s regulation as those apps do not fall under the “wellness” app category43. However, all six apps are not currently updated with an average time since last updated being 1121 days (3.07 years ago). Of note, while these apps were not updated recently, the psychoeducation they provided was so general that the content was not out of date. Still, considering that these are the apps most readily accessible to people with schizophrenia today it is clear that the potential of apps to increase access to care has yet to be fulfilled. Furthermore, the scarcity of clinically appropriate schizophrenia apps on Apple App Store compared to Google Play App Store raises a concern as this disparity can potentially induce health inequalities.

Our results suggest clear and tangible next steps. For research to accelerate to increase access to care, it is necessary to either build apps on non-specific platforms or to make apps built on specific platforms directly available for people to use. While advanced apps are being studied, there is a clear need to provide simple but up to date apps directly on the Apple and Android marketplaces so that people with schizophrenia can at least benefit from higher quality psychoeducation and app offerings.

Our results also suggest a broader question around when an app is necessary for schizophrenia specifically versus when a more transdiagnostic app will suffice. For example, medication tracking is a common feature across nearly every health condition and the added value of a schizophrenia specific vs general medication tracker remains an open question. Similarly, apps which help support people to engage in regular physical activity, adopt healthy eating patterns, quit smoking or even or manage common physical health conditions such as type-2 diabetes are theoretically just as important (or more so) for use in schizophrenia as the general population44. In our team’s work with the MIND website which evaluates apps, we often find ourselves helping people create toolkits of apps that utilize useful features across a range of apps to create the right set of resources for each patient. Research onto a common or transdiagnostic set of app functions for mental health, including schizophrenia, could help focus schizophrenia research on the unique challenges of the field and avoid unnecessary duplication of work.

Our findings expand on prior research results that support our results. Prior studies from our team have examined the top 10 apps for schizophrenia and found similar results28,45, but those studies did not exhaustively search for every app as we did here. Another review found that the number of commercially available apps with academic evidence from across all health fields is scarce but did not focus on schizophrenia and is based on older 2017 data46. Our results complement past reviews of research apps for people with schizophrenia22,23 that also found few available for patients although here we found nearly twice the number of research apps as compared to prior studies – perhaps reflecting accelerating interest in this space.

Like all reviews, ours has several limitations. We only search for research papers in English and are aware that given the many diverse names used to characterize this research, our search term may have missed some studies. However, a primary purpose of the review was to gain an assessment of the extent to which apps in readily-accessed research studies are aligned with those widely available on the marketplace, and there is no reason to believe that any missed studies more difficult to identify would reveal a preponderance of research apps in a way that would change our results. Our marketplace search was exhaustive, but we also realize searches from different regions (ie outside of the United States) may yield different results such as emerging work from China47. A search with more keywords may have included more apps but given only 1.1% of the returned results were relevant, we felt our search was already comprehensive.

Data availability

All data are presented in the paper or shared directly on mindApps.org

References

Asher, L., Fekadu, A. & Hanlon, C. Global mental health and schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 31, 193–199 (2018).

Ben-Zeev, D., Buck, B., Kopelovich, S. & Meller, S. A technology-assisted life of recovery from psychosis. npj Schizophr. 5, 1–4 (2019).

Torous, J., Choudhury, T., Barnett, I., Keshavan, M. & Kane, J. Smartphone relapse prediction in serious mental illness: a pathway towards personalized preventive care. World Psychiatry 19, 308 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Enhancing attention and memory of individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis with mHealth technology. Asian J. Psychiatry 58, 102587.v (2021).

Torous, J. et al. The growing field of digital psychiatry: current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry 20, 318–335 (2021).

Young, A. S. et al. Mobile phone and smartphone use by people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Serv. 71, 280–283 (2020).

Lee, K., Bejerano, I. L., Han, M. & Choi, H. S. Willingness to use smartphone apps for lifestyle management among patients with schizophrenia. Arch. Psychiatric Nursing 33, 329–336 (2019).

Torous, J., Wisniewski, H., Liu, G. & Keshavan, M. Mental health mobile phone app usage, concerns, and benefits among psychiatric outpatients: comparative survey study. JMIR Mental Health 5, e11715 (2018).

Iliescu, R., Kumaravel, A., Smurawska, L., Torous, J. & Keshavan, M. Smartphone ownership and use of mental health applications by psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 299, 113806 (2021).

Naslund, J. A., Aschbrenner, K. A. & Bartels, S. J. How people with serious mental illness use smartphones, mobile apps, and social media. Psychiatric Rehabilit. J. 39, 364 (2016).

Firth, J. & Torous, J. Smartphone apps for schizophrenia: a systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 3, e4930 (2015).

Torous, J. & Roux, S. Patient-driven innovation for mobile mental health technology: case report of symptom tracking in schizophrenia. JMIR Mental Health 4, e7911 (2017).

Torous, J., Myrick, K. J., Rauseo-Ricupero, N. & Firth, J. Digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Mental Health 7, e18848 (2020).

Behavioral Health Workforce Report. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/behavioral-health-workforce-report.pdf.

Keynejad, R., Spagnolo, J. & Thornicroft, G. WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: updated systematic review on evidence and impact. Evidence-Based Mental Health 24, 124–130 (2021).

Ben-Zeev, D. The digital mental health genie is out of the bottle. Psychiatric Serv. 71, 1212–1213 (2020).

Ben-Zeev, D. et al. Development and usability testing of FOCUS: a smartphone system for self-management of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilit. J. 36, 289 (2013).

Torous, J. et al. Towards a consensus around standards for smartphone apps and digital mental health. World Psychiatry 18, 97 (2019).

Mozilla. Top mental health & prayer apps fail at privacy, security. Mozilla Foundation. Retrieved from https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/blog/top-mental-health-and-prayer-apps-fail-spectacularly-at-privacy-security/.

Goldberg, S. B., Lam, S. U., Simonsson, O., Torous, J. & Sun, S. Mobile phone-based interventions for mental health: A systematic meta-review of 14 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. PLOS Digital Health 1, e0000002 (2022).

Ghaemi, S. N., Sverdlov, O., van Dam, J., Campellone, T. & Gerwien, R. A Smartphone-Based Intervention as an Adjunct to Standard-of-Care Treatment for Schizophrenia: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Formative Res. 6, e29154 (2022).

Camacho, E., Levin, L. & Torous, J. Smartphone apps to support coordinated specialty care for prodromal and early course schizophrenia disorders: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e16393 (2019).

Rauch, L. R. “Mind the Gap (S)“in Mental Health Care. How Mhealth Applications are Integrated in Clinical Practice for Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: A Scoping Review (University of Twente, 2022).

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

Lagan, S. et al. Mental health app evaluation: Updating the American Psychiatric Association’s framework through a stakeholder-engaged workshop. Psychiatric Serv. 72, 1095–1098 (2021).

Henson, P., David, G., Albright, K. & Torous, J. Deriving a practical framework for the evaluation of health apps. Lancet Digital Health 1, e52–e54 (2019).

Lagan, S., Sandler, L. & Torous, J. Evaluating evaluation frameworks: a scoping review of frameworks for assessing health apps. BMJ Open 11, e047001 (2021).

Wisniewski, H. et al. Understanding the quality, effectiveness and attributes of top-rated smartphone health apps. Evidence-Based Mental Health 22, 4–9 (2019).

Edemekong, P. F., Annamaraju, P., & Haydel, M. J. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (StatPearls Publishing, 2018).

Torous, J. et al. Characterizing smartphone engagement for schizophrenia: results of a naturalist mobile health study. Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses (2017).

Krzystanek, M. et al. The effect of smartphone-based cognitive training on the functional/cognitive markers of schizophrenia: a one-year randomized study. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3681 (2020).

Krzystanek, M., Borkowski, M., Skałacka, K. & Krysta, K. A telemedicine platform to improve clinical parameters in paranoid schizophrenia patients: Results of a one-year randomized study. Schizophr. Res. 204, 389–396 (2019).

Redzisz, M. Krzystanek: I don’t know the word “impossible”. Sztuczna Inteligencja (2020). Available at: https://www.sztucznainteligencja.org.pl/en/krzystanek-i-dont-know-the-word-impossible/.

Garland, A. F., Jenveja, A. K. & Patterson, J. E. Psyberguide: A useful resource for mental health apps in primary care and beyond. Families Syst. Health 39, 155 (2021).

Schizophrenia guide—apps on google play. play.google.com. Available at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.andromo.dev667101.app757058&hl=en_US&gl=US.

Home remedies for Schizophreni—apps on Google Play. play.google.com. Available at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.memi.HoRemedieFSchizoph&hl=en_US&gl=US.

Remedies For Schizophrenia—Apps on Google Play. Play.google.com. Available at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.ChandSekh.RemdFrSchizop&hl=en_US&gl=US.

Van Strater, A. C. & Bogers, J. P. Interaction of St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) with clozapine. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 27, 121–124 (2012).

Understanding Schizophrenia—Apps on Google Play. play.google.com. Available at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.How.to.Understand.Schizophrenia&hl=en_US&gl=US.

Schizophrenia Guide - Apps on Google Play. play.google.com. Available at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.Schizophrenia.Information.to.know&hl=en_US&gl=US.

Facts about schizophrenia—apps on Google Play. play.google.com. Available at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.schizophrenia.fact&hl=en_US&gl=US.

Abuse, S. & Administration, M. H. S. Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 changes on the national survey on drug use and health. CBHSQ Methodology Report (2016).

Torous, J., Stern, A. D. & Bourgeois, F. T. Regulatory considerations to keep pace with innovation in digital health products. npj Digital Med. 5, 1–4 (2022).

Firth, J. et al. A meta‐review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 19, 360–380 (2020).

Mercurio, M. et al. Longitudinal trends in the quality, effectiveness and attributes of highly rated smartphone health apps. Evidence-based Ment. Health 23, 107–111 (2020).

Byambasuren, O., Sanders, S., Beller, E. & Glasziou, P. Prescribable mHealth apps identified from an overview of systematic reviews. NPJ Digital Med. 1, 1–12 (2018).

Zhang, X., Lewis, S., Firth, J., Chen, X., & Bucci, S. Digital mental health in China: a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 51, 2552–2570 (2021).

Kidd, S., McKenzie, K., Wang, W., Agrawal, S. & Voineskos, A. Examining a digital health approach for advancing schizophrenia illness self-management and provider engagement: protocol for a feasibility trial. JMIR Res. Protocols 10, e24736 (2021).

Kidd, S. A. et al. Feasibility and outcomes of a multi-function mobile health approach for the schizophrenia spectrum: App4Independence (A4i). PLoS ONE 14, e0219491 (2019).

Berry, N. et al. Developing a theory-informed smartphone app for early psychosis: learning points from a multidisciplinary collaboration. Front. Psychiatry 11, 602861 (2020).

Bucci, S. et al. Actissist: proof-of-concept trial of a theory-driven digital intervention for psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 1070–1080 (2018).

Bucci, S. et al. Digital interventions in severe mental health problems: lessons from the Actissist development and trial. World Psychiatry 17, 230 (2018).

Granholm, E. et al. Mobile-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for negative symptoms: open single-arm trial with schizophrenia patients. JMIR Ment. Health 7, e24406 (2020).

Depp, C. A., Perivoliotis, D., Holden, J., Dorr, J. & Granholm, E. L. Single-session mobile-augmented intervention in serious mental illness: a three-arm randomized controlled trial. Schizophr. Bull. 45, 752–762 (2019).

Granholm, E. et al. 18.2 Mobile-assisted cognitive behavior therapy for negative symptoms (mCBTn) in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 45, S118–S118 (2019).

Lewis, S. et al. Smartphone-enhanced symptom management in psychosis: open, randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e17019 (2020).

Cella, M. et al. Blending active and passive digital technology methods to improve symptom monitoring in early psychosis. Early Intervention Psychiatry 13, 1271–1275 (2019).

Palmier-Claus, J. E. et al. The feasibility and validity of ambulatory self-report of psychotic symptoms using a smartphone software application. BMC Psychiatry 12, 1–10 (2012).

Lim, M. H., et al. A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in young people with psychosis. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. 55, 877–889.

Lim, M. H. et al. A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in youth mental health. Front. Psychiatry 10, 604 (2019).

Buck, B. et al. mHealth-assisted detection of precursors to relapse in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 12, 642200 (2021).

Adler, D. A. et al. Predicting early warning signs of psychotic relapse from passive sensing data: an approach using encoder-decoder neural networks. JMIR mHealth uHealth 8, e19962 (2020).

Buck, B. et al. Capturing behavioral indicators of persecutory ideation using mobile technology. J. Psychiatric Res. 116, 112–117 (2019).

Taylor, K. M., Bradley, J., & Cella, M. A novel smartphone‐based intervention targeting sleep difficulties in individuals experiencing psychosis: a feasibility and acceptability evaluation. Psychol. Psychother.: Theory Res. Practice 95, 717–737 (2022).

Eisner, E. et al. Feasibility of using a smartphone app to assess early signs, basic symptoms and psychotic symptoms over six months: a preliminary report. Schizophr. Res. 208, 105–113 (2019).

Eisner, E. et al. Development and long-term acceptability of ExPRESS, a mobile phone app to monitor basic symptoms and early signs of psychosis relapse. JMIR mHealth uHealth 7, e11568 (2019).

Achtyes, E. D. et al. Off-hours use of a smartphone intervention to extend support for individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders recently discharged from a psychiatric hospital. Schizophr. Res. 206, 200–208 (2019).

Jonathan, G., Carpenter-Song, E. A., Brian, R. M. & Ben-Zeev, D. Life with FOCUS: a qualitative evaluation of the impact of a smartphone intervention on people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilit. J. 42, 182 (2019).

Ben-Zeev, D., Brian, R. M., Aschbrenner, K. A., Jonathan, G. & Steingard, S. Video-based mobile health interventions for people with schizophrenia: Bringing the “pocket therapist” to life. Psychiatric Rehabilit. J. 41, 39 (2018).

Sedgwick, O., Hardy, A., Greer, B., Newbery, K. & Cella, M. “I wanted to do more of the homework!”—Feasibility and acceptability of blending app‐based homework with group therapy for social cognition in psychosis. J. Clin. Psychol. 77, 2701–2724 (2021).

Kim, S. W. et al. Development and feasibility of smartphone application for cognitive‐behavioural case management of individuals with early psychosis. Early Intervention Psychiatry 12, 1087–1093 (2018).

Smelror, R. E., Bless, J. J., Hugdahl, K. & Agartz, I. Feasibility and acceptability of using a mobile phone app for characterizing auditory verbal hallucinations in adolescents with early-onset psychosis: exploratory study. JMIR Formative Res. 3, e13882 (2019).

Visser, L., Sinkeviciute, I., Sommer, I. E. & Bless, J. J. Training switching focus with a mobile‐application by a patient suffering from AVH, a case report. Scand. J. Psychol. 59, 59–61 (2018).

Fulford, D. et al. Do cognitive impairments limit treatment gains in a standalone digital intervention for psychosis? A test of the digital divide. Schizophr. Res.: Cognition 28, 100244 (2022).

Fulford, D. et al. Preliminary outcomes of an ecological momentary intervention for social functioning in schizophrenia: pre-post study of the motivation and skills support app. JMIR Ment. Health 8, e27475 (2021).

Fulford, D. et al. Development of the Motivation and Skills Support (MASS) social goal attainment smartphone app for (and with) people with schizophrenia. J. Behav. Cogn. Ther. 30, 23–32 (2020).

Kreyenbuhl, J. et al. Development and feasibility testing of a smartphone intervention to improve adherence to antipsychotic medications. Clinical Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 12, 152–167 (2019).

Steare, T. et al. A qualitative study of stakeholder views on the use of a digital app for supported self-managementin early intervention services for psychosis. BMC psychiatry 21, 1–2 (2021).

Steare, T. et al. Smartphone-delivered self-management for first-episode psychosis: the ARIES feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 10, e034927 (2020).

Steare, T. et al. App to support Recovery in Early Intervention Services (ARIES) study: protocol of a feasibility randomised controlled trial of a self-management Smartphone application for psychosis. BMJ open 9, e025823 (2019).

Han, M., Lee, K., Kim, M., Heo, Y., & Choi, H. Effects of a metacognitive smartphone intervention with weekly mentoring sessions for individuals with schizophrenia: a quasi-experimental study. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 1-11 (2022).

Haesebaert, F. et al. PLAN-e-PSY, a mobile application to improve case management and patient’s functioning in first episode psychosis: protocol for an open-label, multicentre, superiority, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 11, e050433 (2021).

Schlosser, D. A. et al. Efficacy of PRIME, a mobile app intervention designed to improve motivation in young people with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 1010–1020 (2018).

Schlosser, D. et al. Feasibility of PRIME: a cognitive neuroscience-informed mobile app intervention to enhance motivated behavior and improve quality of life in recent onset schizophrenia. JMIR Res. Protocols 5, e5450 (2016).

Barbeito, S. et al. Mobile app–based intervention for adolescents with first-episode psychosis: study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychiatry 10, 27 (2019).

Hui, C. L. M. et al. ReMind, a smartphone application for psychotic relapse prediction: a longitudinal study protocol. Early Intervention Psychiatry 15, 1659–1666 (2021).

Bonet, L., Torous, J., Arce, D., Blanquer, I. & Sanjuan, J. ReMindCare app for early psychosis: pragmatic real world intervention and usability study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 8, e22997 (2020).

Bonet, L., Torous, J., Arce, D., Blanquer, I. & Sanjuán, J. ReMindCare, an app for daily clinical practice in patients with first episode psychosis: A pragmatic real‐world study protocol. Early Intervention psychiatry 15, 183–192 (2021).

Hardy, A. How inclusive, user-centered design research can improve psychological therapies for psychosis: development of SlowMo. JMIR Ment. Health 5, e11222 (2018). et a.

Gire, N. et al. ‘Care co-ordinator in my pocket’: a feasibility study of mobile assessment and therapy for psychosis (TechCare). BMJ Open 11, e046755 (2021).

Gire, N., Mohmed, N., McKeown, M., Duxbuy, J. & Husain, N. Development of a mHealth Intervention (TechCare) for first episode psychosis: a focus group study with mental health professionals. BJPsych Open 8, S52–S52 (2022).

Husain, N. et al. TechCare: mobile assessment and therapy for psychosis–an intervention for clients in the early intervention service: a feasibility study protocol. SAGE Open Med. 4, 2050312116669613 (2016).

Jongeneel, A. et al. Reducing distress and improving social functioning in daily life in people with auditory verbal hallucinations: study protocol for the ‘Temstem’randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 8, e020537 (2018).

Stürup, A. E. et al. TAILOR–tapered discontinuation versus maintenance therapy of antipsychotic medication in patients with newly diagnosed schizophrenia or persistent delusional disorder in remission of psychotic symptoms: study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials 18, 1–12 (2017).

Weintraub, M. J. et al. App-enhanced transdiagnostic CBT for adolescents with mood or psychotic spectrum disorders. J. Affective Disorders 311, 319–326 (2022).

de Almeida, R. S., Couto, A., Marques, A., Queirós, C. & Martins, C. Mobile application for self-management in schizophrenia: a pilot study. J. Technol. Human Serv. 36, 179–190 (2018).

ALMEIDA, R. F. et al. Development of weCope, a mobile app for illness self-management in schizophrenia. Arch. Clin. Psychiatry (São Paulo) 46, 1–4 (2019).

Nicholson, J., Wright, S. M. & Carlisle, A. M. Pre-post, mixed-methods feasibility study of the WorkingWell mobile support tool for individuals with serious mental illness in the USA: a pilot study protocol. BMJ Open 8, e019936 (2018).

Nicholson, J., Wright, S. M., Carlisle, A. M., Sweeney, M. A. & McHugo, G. J. The WorkingWell mobile phone app for individuals with serious mental illnesses: proof-of-concept, mixed-methods feasibility study. JMIR Mental Health 5, e11383 (2018).

Bain, E. E. et al. Use of a novel artificial intelligence platform on mobile devices to assess dosing compliance in a phase 2 clinical trial in subjects with schizophrenia. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 5, e7030 (2017).

Barnett, I. et al. Relapse prediction in schizophrenia through digital phenotyping: a pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 1660–1666 (2018).

Torous, J., Kiang, M. V., Lorme, J. & Onnela, J. P.New tools for new research in psychiatry: a scalable and customizable platform to empower data driven smartphone research. JMIR Mental Health 3, e5165 (2016).

Torous, J. et al. Characterizing the clinical relevance of digital phenotyping data quality with applications to a cohort with schizophrenia. NPJ Digital Med. 1, 1–9 (2018).

Dabit, S., Quraishi, S., Jordan, J. & Biagianti, B. Improving social functioning in people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders via mobile experimental interventions: Results from the CLIMB pilot trial. Schizophr. Res.: Cogn. 26, 100211 (2021).

Biagianti, B., Schlosser, D., Nahum, M., Woolley, J. & Vinogradov, S. SU133. CLIMB: a mobile intervention to enhance social functioning in people with psychotic disorders: results from a feasibility study. Schizophr. Bull. 43, S210–S210 (2017).

Biagianti, B., Schlosser, D., Nahum, M., Woolley, J. & Vinogradov, S. Creating live interactions to mitigate barriers (CLIMB): a mobile intervention to improve social functioning in people with chronic psychotic disorders. JMIR Ment. Health 3, e6671 (2016).

Ben-Zeev, D. et al. A smartphone intervention for people with serious mental illness: fully remote randomized controlled trial of CORE. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e29201 (2021).

Fichtenbauer, I., Priebe, S. & Schrank, B. Die deutsche Version von DIALOG+ bei PatientInnen mit Psychose–eine Pilotstudie. Psychiatrische Praxis 46, 376–380 (2019).

Priebe, S. et al. The effectiveness of a patient-centred assessment with a solution-focused approach (DIALOG+) for patients with psychosis: a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial in community care. Psychother. Psychosomatics 84, 304–313 (2015).

Omer, S., Golden, E. & Priebe, S. Exploring the mechanisms of a patient-centred assessment with a solution focused approach (DIALOG+) in the community treatment of patients with psychosis: a process evaluation within a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 11, e0148415 (2016).

Zarbo, C. et al. Assessing adherence to and usability of Experience Sampling Method (ESM) and actigraph in patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder: a mixed-method study. Psychiatry Res. 314, 114675 (2022).

Minor, K. S. et al. Personalizing interventions using real-world interactions: Improving symptoms and social functioning in schizophrenia with tailored metacognitive therapy. J. Consulting. Clin. Psychol. 90, 18 (2022).

Minor, K. S., Davis, B. J., Marggraf, M. P., Luther, L. & Robbins, M. L. Words matter: Implementing the electronically activated recorder in schizotypy. Personality Disorders: Theory Res. Treatment 9, 133 (2018).

Moran, E. K., Culbreth, A. J., Kandala, S. & Barch, D. M. From neuroimaging to daily functioning: a multimethod analysis of reward anticipation in people with schizophrenia. J. Abnormal Psychol. 128, 723 (2019).

Lopez-Morinigo, J. D. et al. Use of ecological momentary assessment through a passive smartphone-based app (eB2) by patients with schizophrenia: acceptability study. J. Medical Internet Res. 23, e26548 (2021).

Gumley, A. I. et al. Digital smartphone intervention to recognise and manage early warning signs in schizophrenia to prevent relapse: the EMPOWER feasibility cluster RCT. Health Technol. Assessment (Winchester, England) 26, 1 (2022).

Allan, S. et al. Developing a hypothetical implementation framework of expectations for monitoring early signs of psychosis relapse using a mobile app: qualitative study. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e14366 (2019).

Niendam, T. A. et al. Enhancing early psychosis treatment using smartphone technology: a longitudinal feasibility and validity study. J. Psychiatric Res. 96, 239–246 (2018).

Lahti, A. C., Wang, D., Pei, H., Baker, S. & Narayan, V. A. Clinical utility of wearable sensors and patient-reported surveys in patients with schizophrenia: Noninterventional, observational study. JMIR Ment. Health 8, e26234 (2021).

Raugh, I. M. et al. Geolocation as a digital phenotyping measure of negative symptoms and functional outcome. Schizophr. Bull. 46, 1596–1607 (2020).

Raugh, I. M. et al. Digital phenotyping adherence, feasibility, and tolerability in outpatients with schizophrenia. J. Psychiatric Res. 138, 436–443 (2021).

Moitra, E., Park, H. S. & Gaudiano, B. A. Development and initial testing of an mHealth transitions of care intervention for adults with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders immediately following a psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatric Q. 92, 259–272 (2021).

Berrouiguet, S. et al. Ecological assessment of clinicians’ antipsychotic prescription habits in psychiatric inpatients: a novel web-and mobile phone–based prototype for a dynamic clinical decision support system. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e5954 (2017).

Berrouiguet, S. et al. Development of a web-based clinical decision support system for drug prescription: non-interventional naturalistic description of the antipsychotic prescription patterns in 4345 outpatients and future applications. PLoS ONE 11, e0163796 (2016).

Shvetz, C., Gu, F., Drodge, J., Torous, J. & Guimond, S. Validation of an ecological momentary assessment to measure processing speed and executive function in schizophrenia. npj Schizophr. 7, 1–9 (2021).

Ranjan, T., Melcher, J., Keshavan, M., Smith, M., & Torous, J. Longitudinal symptom changes and association with home time in people with schizophrenia: an observational digital phenotyping study. Schizophr Res. 243, 64–69 (2022).

Henson, P., Rodriguez-Villa, E. & Torous, J. Investigating associations between screen time and symptomatology in individuals with serious mental illness: longitudinal observational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e23144 (2021).

Terp, M., Jørgensen, R., Laursen, B. S., Mainz, J. & Bjørnes, C. D. A smartphone app to foster power in the everyday management of living with schizophrenia: qualitative analysis of young adults’ perspectives. JMIR Ment. Health 5, e10157 (2018).

Bell, I. H. et al. Smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment and intervention in a coping-focused intervention for hearing voices (SAVVy): study protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials 19, 1–13 (2018).

Michel, C. et al. An ecological momentary assessment study of age effects on perceptive and non-perceptive clinical high-risk symptoms of psychosis. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry 31, 1–12 (2022).

Reinertsen, E. et al. Continuous assessment of schizophrenia using heart rate and accelerometer data. Physiol. Measurement 38, 1456 (2017).

Reinertsen, E., Shashikumar, S. P., Shah, A. J., Nemati, S. & Clifford, G. D. Multiscale network dynamics between heart rate and locomotor activity are altered in schizophrenia. Physiol. Measurement 39, 115001 (2018).

Vaessen, T. et al. ACT in daily life in early psychosis: an ecological momentary intervention approach. Psychosis 11, 93–104 (2019).

Reininghaus, U. et al. Efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy in daily life (ACT-DL) in early psychosis: study protocol for a multi-centre randomized controlled trial. Trials 20, 1–12 (2019).

van Aubel, E. et al. Blended care in the treatment of subthreshold symptoms of depression and psychosis in emerging adults: a randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy in daily-life (ACT-DL). Behav. Res. Ther. 128, 103592 (2020).

Hanssen, E. et al. An ecological momentary intervention incorporating personalised feedback to improve symptoms and social functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 284, 112695 (2020).

Meyer, N. et al. Capturing rest-activity profiles in schizophrenia using wearable and mobile technologies: development, implementation, feasibility, and acceptability of a remote monitoring platform. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 6, e8292 (2018).

Meyer, N. et al. The temporal dynamics of sleep disturbance and psychopathology in psychosis: a digital sampling study. Psychol. Med. 52, 1–10 (2021).

Bell, I. H. et al. Smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment and intervention in a blended coping-focused therapy for distressing voices: Development and case illustration. Internet Interv. 14, 18–25 (2018).

Kumar, D. et al. A mobile health platform for clinical monitoring in early psychosis: implementation in community-based outpatient early psychosis care. JMIR Ment. Health 5, e8551 (2018).

Traber-Walker, N. et al. Evaluation of the combined treatment approach “robin”(standardized manual and smartphone app) for adolescents at clinical high risk for psychosis. Front. Psychiatry 10, 384 (2019).

Berry, A., Drake, R. J., Butcher, I. & Yung, A. R. Examining the feasibility, acceptability, validity and reliability of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep measures in people with schizophrenia. Ment. Health Physical Activity 21, 100415 (2021).

Cinemre, B., Gulerce, M. & Gulkesen, K. H. A self-management app for patients with schizophrenia: a pilot study. Stud. Health Technol. Informatics 289, 357–361 (2022).

Parrish, E. M. et al. Remote ecological momentary testing of learning and memory in adults with serious mental illness. Schizophr. Bull. 47, 740–750 (2021).

Sigurðardóttir, S. G., Islind, A. S. & Óskarsdóttir, M. Collecting Data from a Mobile App and a Smartwatch Supports Treatment of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. In Challenges of Trustable AI and Added-Value on Health. 239–243. (IOS Press, 2022).

Atkins, A. S. et al. Validation of the tablet-administered Brief Assessment of Cognition (BAC App). Schizophr. Res. 181, 100–106 (2017).

Atkins, A. et al. M25. development and validation of the brief assessment of validation in schizophrenia (BAC-App). Schizophr. Bull. 43, S220 (2017).

Zhu, X. et al. A mobile health application-based strategy for enhancing adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia. Arch. Psychiatric Nurs. 34, 472–480 (2020).

Yu, Y. et al. New path to recovery and well-being: cross-sectional study on Wechat use and endorsement of Wechat-based mHealth among people living with schizophrenia in China. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e18663 (2020).

Xiao, S., Li, T., Zhou, W., Shen, M. & Yu, Y. WeChat-based mHealth intention and preferences among people living with schizophrenia. PeerJ 8, e10550 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Spencer Roux, Kerris Myrick, and Charley Stroymer for providing their insight and feedback about certain commercial marketplace apps. This work was supported by a grant from the Sydney Baer Junior Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T. conceptualized and supervised the study. S.K. and J.T. performed the literature search and data extraction. S.K., D.J. and J.T. carried out the screening and selection of articles. S.K. and J.T. carried out the screening and selection of apps. S.K. and J.T. performed all data analyses. The manuscript was drafted by S.K., J.F. and J.T. and all authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, S., Firth, J., Joshi, D. et al. Accessibility and availability of smartphone apps for schizophrenia. Schizophr 8, 98 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00313-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00313-0