Abstract

Magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene (MATTG) recently emerged as a highly tunable platform for studying correlated phases of matter, such as correlated insulators and superconductivity. Superconductivity occurs in a range of doping levels that is bounded by van Hove singularities, which stimulates the debate of the origin and nature of superconductivity in this material. In this work, we discuss the role of spin-fluctuations arising from atomic-scale correlations in MATTG for the superconducting state. We show that in a phase diagram as a function of doping (ν) and temperature, nematic superconducting regions are surrounded by ferromagnetic states and that a superconducting dome with Tc ≈ 2 K appears between the integer fillings ν = −2 and ν = −3. Applying a perpendicular electric field enhances superconductivity on the electron-doped side which we relate to changes in the spin-fluctuation spectrum. We show that the nematic unconventional superconductivity leads to pronounced signatures in the local density of states detectable by scanning tunneling spectroscopy measurements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the discovery of superconductivity and correlated insulating states in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene (MATBG)1,2, twisted van der Waals materials have become indispensable for the design of novel quantum materials at will3. In the quickly developing field of twistronics4, tremendous theoretical5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 and experimental27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 efforts have been undertaken to unravel the nature of strong correlations47,48 and to access new moiré engineered structures with twisted double-bilayer graphene49,50,51,52, twisted trilayer graphene53,54,55,56,57, transition metal dichalcogenide homobilayers and heterobilayers58,59,60,61,62 as well as other materials63,64,65 at the frontier of condensed matter research3.

These systems are fascinating because of the precise control of electronic properties and correlations that can be achieved by tuning twist angle1,2, doping level1,2,27, temperature28,29, pressure30,66, and external screening31,32,33,67. The appearance of almost flat bands at so-called “magic angles,” first predicted in early theoretical works68,69,70,71, puts a variety of exotic correlated phases within experimental reach, including correlated insulators27,28,29,30,31,32,37,40,41,42,43,44,45,46, orbital ferromagnetism27,38,39,72, and magnetic field induced Chern insulators33,34,35,36,73.

Among the findings that have sparked the most interest in the field of twistronics is the discovery of robust and reproducible superconductivity in MATBG1,27,30, with preliminary evidence for possible superconductivity also present in twisted double-bilayer graphene49,50,51, ABC trilayer graphene aligned to hexagonal boron nitride74, and twisted transition metal dichalcogenides58. Very recently, another graphitic moiré system that features reproducible, highly tunable superconductivity (as well as correlated insulators) has been discovered: magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene (MATTG)53,54,55, where the twist angle alternates by +θ and −θ between each graphene layer [see Fig. 1a]. Experiments on MATTG find superconductivity at doping levels between integer fillings of ν = −2 and ν = −3, where ν corresponds to the number of electrons per moiré unit cell relative to charge neutrality53,54,55. Additionally, refs. 53,55 report superconductivity between fillings of ν = 2 and ν = 3, which is much weaker in ref. 54 but can be stabilized upon application of a perpendicular displacement field. Furthermore, displacement fields are found to give rise to additional superconducting (SC) features between fillings of ν = 1 and ν = 2 and between ν = −1 and ν = −253. This demonstrates that (i) superconductivity in MATTG seems to preferentially appear in between integer fillings of the flat bands and that (ii) superconductivity in MATTG can be readily tuned through a perpendicular displacement field, which makes MATTG a particularly attractive platform for studying strongly correlated physics.

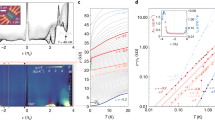

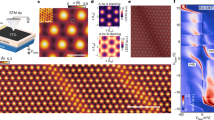

a The atomic structure of MATTG consists of three superimposed graphene sheets. While the outer graphene sheets are aligned (AA stacked) and untwisted, the inner layer (black) is twisted at an angle θ (−θ) relative to the lower (upper) sheet. b Band structure of MATTG at θ = 1.61°. Long-range electron–electron interactions are taken into account through Hartree corrections that lead to a doping-dependent band structure. The flat band dispersion is strongly affected by the filling factor ν (blue: ν = +3, black: ν = 0, red: ν = −3), whereas the Dirac cone remains unaffected. c Local density of states (LDOS) in the outer layer of MATTG for ν = −2.5. The left panel clearly shows that the flat bands are mostly localized in the AAA regions. The right panel shows the spatial distribution of the LDOS in the top layer at energies of the remote valence band (RV1), remote conduction band (RC1), valence flat band (VFB), and conduction flat band (CFB), reflecting the C3z symmetry of the non-interacting Hamiltonian. d Phase diagram of MATTG for θ = 1.61° around ν = −2.5. Our numerical calculations reveal a superconducting dome driven by low-energy AFM spin-fluctuations that range from ν = −2.35 to ν = −2.7 with an upper critical temperature of Tc ≈ 2 K. The average amplitude of the order parameter \(| \bar{{{\Delta }}}|\) is reduced with increasing temperature and vanishes toward the integer fillings ν = −3 and ν = −2, where ferromagnetic phases (FM) dominate. At high temperatures, the system remains paramagnetic (PM). e, f Magnetic correlations in MATTG at zero (left) and nonzero ΔD = ±30 meV (right) perpendicular displacement field. The lower panel displays the critical Hubbard interaction strength Uc needed for the onset of magnetic order as a function of filling. The type of magnetic order is color-coded through an order parameter that continuously interpolates between AFM and FM order (red: FM, yellow: AFM, for a definition, see Supplemental Methods). The upper panels display a sketch [which is confirmed quantitatively for filling between ν = −3 and ν = −2 in d] of parameter regions that can host unconventional SC driven by AFM spin-fluctuations for U ≈ 5 eV (dashed black horizontal line). As magnetic interactions can only provide the pairing glue for superconductivity as long as the system remains paramagnetic, i.e. U < Uc, this mechanism supports SC at ν = −2 − δ and around ν = +2 + δ. Screening effects caused by the dielectric environment may change the position of the superconducting domes to different fillings (blue to green SC domes). Applying an electric field to the sample (f) enhances superconducting regions at the electron-doped side at ν = +2 + δ.

The coexistence of correlated insulating and SC states in MATTG has further elicited questions about their intrinsic relationship in graphene-based moiré materials. In particular, the question of whether the SC states are of unconventional nature and driven by electron–electron interaction, or conventional and mediated by electron–phonon coupling, is still intensely debated at the moment even for MATBG24,32,48.

The aim of this work is to shed light on this controversial question by presenting how unconventional superconductivity in MATTG can arise from spin fluctuation exchange on the atomic scale. Starting from a fully atomistic tight-binding (TB) description of the system, we investigate the effect of long-ranged electron–electron interactions on the phase diagram of MATTG. To this end, we derive a microscopic pairing interaction \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\) in the fluctuation–exchange approximation (FLEX) and solve the non-linear Bogoliubov-de Gennes (BdG) equations as a function of filling and temperature. Our results indicate that spin-singlet superconductivity can be driven by magnetic fluctuations in between integer fillings. At the same time, superconductivity is shown to depend sensitively on the value of the carbon pz Hubbard-U, which is influenced by experimental details such as environmental screening and the application of fields, and that it can be moved from one between-integer filling to another. For a suitably chosen interaction strength and without a displacement field, we find superconductivity is strongest in between fillings of ν = −2 and ν = −3 (with critical temperature Tc ≈ 2 K) as well as around ν = +2 + δ, while being surrounded by ferromagnetic (FM), semi-metallic or metallic states. We show that, for fixed interaction strength, a perpendicular electric field weakens the SC dome on the hole-doped side but enhances superconductivity at doping levels around ν = +2 + δ. Hereby we demonstrate that correlated and SC features driven by electronic interactions in MATTG are highly tunable by a perpendicular electric field which corroborates recent experimental findings53,54,55, in particular those of ref. 54. We then analyze the nature of the SC state further and show that according to our atomistic calculations MATTG hosts unconventional, nematic d-wave superconductivity that displays clear signatures of C3z symmetry breaking in the local density of states (LDOS).

Results

Atomic, electronic, and magnetic structure

The atomic structure of MATTG is constructed from three stacked sheets of graphene, where the outer layers (l = 1, 3) are perfectly aligned and the middle layer (l = 2) is twisted by ±θ relative to the encapsulating layers, as schematically depicted in Fig. 1a. Different regions in the moiré unit cell of MATTG can be labeled according to the stacking sequence of the trilayer. At the center of rotation, the stacking is of AAA type, where carbon atoms of all layers reside vertically displaced on top of each other, as shown in the inset of Fig. 1. In between the AAA regions, the local geometry successively changes from ABA to domain wall (DW) and BAB stacking. The atomic structure described is invariant under the mirror reflection symmetry σh that exchanges the upper and lower layer (1 ↔ 3, 2 ↔ 2) and under threefold rotations around the \(\hat{z}\) axis described by the point group C3z.

To account for lattice reconstruction effects, which have been shown to be important in the field of twistronics47, we first relax the positions of MATTG using classical force fields (see “Methods”). According to the reflection symmetry σh, we find that the central layer remains flat, while the atoms of the outer layers undergo significant out-of-plane displacements, which is in good agreement with other work75,76. In fact, recent results75 indicate that perfect alignment between the outer layers, as considered in this study, is energetically favored over a relative shift between the outer layers, i.e., AAB/BAA stacking, and hence should be the most relevant stacking configuration that is naturally realized in experimental samples.

To model the electronic structure of MATTG, we use a microscopic TB parametrization for the pz orbitals of the carbon atoms77 combined with ab initio density functional theory (DFT) simulations (see Supplementary Methods and “Methods”). To match the dispersion obtained from DFT, we complement the TB model with an additional onsite potential of −35 meV acting on the middle layer. As a result, the flat bands intersect with the Dirac cone below the Dirac point, which was also noted in previous work for MATTG by Lopez-Bezanilla and Lado76. As shown in Fig. 1b, we find that for θ = 1.61°, the low-energy electronic structure of MATTG consists of a set of flat bands (similar to MATBG), which are intersected by a Dirac cone with a large Fermi velocity75,76,78 compared to the flat band kinetic energy scales. The twist angle investigated here is very close to the magic angle of 1.54°, which exhibits the smallest flat band width79.

In MATBG, long-ranged electron–electron interactions were found to strongly alter the electronic structure, which has important consequences for the observation of broken symmetry phases. MATTG is an ostensibly similar system, and therefore, we also treat the long-ranged part of the electron interactions using a self-consistent Hartree theory in the atomistic TB framework (see Supplementary Methods and “Methods”)5,80. Through the Hartree potential, the electronic structure of MATTG in the normal state acquires a filling dependence, which shifts the electronic bands to higher or lower energies depending on the doping level. We show in Fig. 1b that the dispersion of the flat bands of MATTG in the normal state is indeed very sensitive to long-ranged electron interactions: removing electrons lowers the K-point energies of the flat bands relative to the Γ-point, which is similar to the doping dependence of MATBG5,80, and is accompanied by a global shift of the flat bands relative to the Dirac cone to more negative energies. In contrast, adding electrons increases the K-point energies of the flat bands relative to the Γ-point, and shifts the whole flat band manifold to higher energies relative to the Dirac cone. The Dirac cone with its large Fermi velocity is insensitive to long-ranged electron interactions.

The LDOS in the outer layer of MATTG, as shown in Fig. 1c for a doping level of ν = −2.5, exhibits large peaks in the AAA regions for energies within the range of the flat bands (the conduction flat band and valence flat band). This behavior is consistent with the earlier prediction that the flat-band physics in MATTG is similar to that of MATBG79. Although the flat bands have their largest spectral weight in the central layer, significant weight is distributed on the outer layers such that the van Hove singularities associated with the flat bands should be observable in scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) experiments. This is shown in the left panel of Fig. 1c, where the flat bands give rise to C3z symmetric signatures in the LDOS. At larger energies (remote conduction band RC1 and remote valence band RV1), the states become more delocalized [see right panel of Fig. 1c].

Having captured the effect of long-range electron–electron interactions in the doping-dependent band structure, we study the influence of the remaining short-ranged terms, i.e., a repulsive Hubbard-U, by calculating the atomistic susceptibility \({\hat{\chi }}_{0}\) in the magnetic channel. To this end, we employ the random phase approximation (RPA) in its static, long-wavelength limit8,9 (see “Methods”). As the effect of the Hartree potential on the band structure of MATTG is very similar to the MATBG case, the consequence we expect is a broader range of twist angles showing correlated states driven by short-range interactions8. For a given filling and temperature (ν, T), the magnetic susceptibility \({\hat{\chi }}_{0}\) contains information about (i) the critical interaction strength Uc, that is the minimal value of U needed to drive the system from the paramagnetic regime (U < Uc) into magnetic order (U≥Uc) and (ii) the type of magnetic order depending on the distribution of magnetic moments in the moiré unit cell.

In Fig. 1e, we show Uc as a function of filling at T = 1.3 K. The color maps indicate the type of magnetic ordering [yellow: antiferromagnetic (AFM) and red: ferromagnetic (FM)]. A precise definition of the order parameter that continuously interpolates from FM to AFM order is given in the Supplemental Methods. We find that small values of Uc are observed at (or close to) the integer fillings ν = ±3, −2, ±1 driving FM order. Small values of Uc indicate that the system is very susceptible to this kind of magnetic order as already a small interaction value U is sufficient to trigger the magnetic instability. Interestingly, for ν = −3, −2, ±1 these dips in Uc are surrounded by AFM regions exhibiting a much larger Uc. Such behavior was previously observed in MATBG7 and indicates that, depending on the value of the Hubbard-U, these AFM instabilities may not be strong enough to actually occur, which opens the door for possible spin-fluctuation mediated superconductivity.

To investigate the influence of an external, perpendicular electric field, we set the onsite energies of the outer layers to ΔD = ±30 meV, which models the presence of a displacement field similar in magnitude (see Supplementary Methods) to that applied in the experiments of ref. 54 to achieve their highest SC transition temperatures. In Fig. 1f, we show the same RPA analysis for this additional interlayer potential. In contrast to what was found without an electric field, we now observe small values of Uc close to ν = +2 electrons. We observe an increase in the small value of Uc at ν = +1, and the value at ν = +3 remains relatively unchanged by the displacement field. Moreover, on the hole-doped side Uc is increased strongly almost over the whole doping range, which is where the lowest values of Uc were observed without a displacement field. Interestingly, now an AFM region which is surrounded by FM regions emerges around ν = +2.5. Within this AFM region, Uc is large, which yields a paramagnetic phase with AFM fluctuations for U < Uc.

Spin-fluctuation-induced superconductivity

To model unconventional superconductivity in MATTG, we assume that Cooper pairs are formed due to intricate effects arising from microscopic electron–electron interactions. Hence, this approach differs from the conventional BCS theory with electron–phonon coupling as the predominant pairing mechanism. In the vicinity of magnetic (semi-metallic or metallic) instabilities described above, a spin-polarized electron may travel through the graphene lattice and polarize the other electrons’ spin around it such that an attractive interaction arises between the electrons and they finally form a bound state81. Technically, we capture this effect of transverse and longitudinal spin-fluctuations by the microscopic pairing vertex \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\), which we derive using the FLEX. We then solve the non-linear BdG equations self-consistently, using the full atomistic FLEX pairing vertex to obtain information about the nature of the SC state (for details see “Methods” section and Supplementary Methods).

When MATTG is doped near ν = −2.5 in the absence of a displacement field, our unconventional BCS theory reveals nematic superconductivity that originates from AFM spin-fluctuation exchange. As shown in Fig. 1, as a function of filling and temperature, the system features an SC dome enclosed by FM instabilities at integer fillings ν = −2 and ν = −3. The transition temperature of the SC phase is substantially influenced by the spin-fluctuation spectrum. As AFM tendencies are weakened with increasing temperature and FM instabilities dominate around the integer fillings, the SC region is effectively confined between ν = −2 and ν = −3 with an upper critical temperature of Tc ≈ 2 K. For even larger temperatures, the flat bands of the system are no longer resolved due to temperature broadening and the system continuously returns to ordering tendencies inherited from the untwisted system9. This can be clearly recognized by the FM ordering tendencies disappearing at high T.

The driving force behind this SC phase originates from low-energy AFM spin-fluctuations81 that can provide an attractive potential for electrons in MATTG. The non-uniform real-space profile of the spin-mediated pairing vertex \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\) in the moiré unit cell (see Supplementary Methods) shows that these attractive components are strongest on nearest-neighbor bonds in the single graphene sheets of MATTG, thus suggesting in-plane Cooper pairs. The low-energy spin-fluctuations are strengthened in the vicinity of the magnetic instability, i.e., when the value of the repulsive Hubbard-U is slightly below the critical interaction strength U ≲ Uc. In this parameter regime, the system shows no magnetic order, but the attractive interactions mediated by the spin fluctuations can provide the pairing glue for unconventional spin-singlet superconductivity between the integer fillings. At the same time, singlet Cooper pairs may not be relevant close to the FM instabilities as the effective interaction \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\) is purely repulsive in the singlet channel.

The only free parameter in our approach is the value of the Hubbard-U, which cannot easily be extracted from first-principles due to a large number of atoms in the moiré unit cell. Besides, transport measurements are very sensitive to the dielectric environment which may screen the interactions more strongly. This can be achieved by, for example, varying the distance between the MATTG sample and the metallic gate(s)32,67, using a dielectric substrate with a larger dielectric constant82 or placing an AB stacked graphene bilayer in the immediate vicinity of the sample31. In our study, we adopt U = 5.1 eV, which is a realistic value for graphene-based materials obtained from first-principles calculations83,84. Choosing this particular value of the Hubbard interaction supports spin-fluctuation induced superconductivity for ν = −2 − δ on the hole-doped side and ν = + 2 + δ on the electron-doped side, which is schematically visualized by the blue SC domes in the top panel of Fig. 1e. Based on our argument, we propose that the SC instabilities can shift to different fillings if the dielectric screening reduces the Hubbard-U to smaller values. For example, if the interaction strength is screened to U = 4.4 eV as visualized by the green dashed line in Fig. 1e, SC domes shift toward AFM regions in the phase diagram where U ≲ Uc. As can be seen in the top panel of the same figure, this results in the formation of two SC domes (green) at fillings ν = −1 − δ on the hole-doped side and at ν = +1 − δ on the electron-doped side.

As recent experiments have demonstrated the displacement field tunability of the SC phase53,54, we further investigate the system in the presence of an electric field (ΔD = ±30 meV), with the results shown in Fig. 1f. We observe that the spin-fluctuation spectrum undergoes major changes such that superconductivity is enhanced at the electron-doped side and an SC dome spreads over almost the entire filling range between ν = + 2 and ν = + 3, which is in agreement with recent experimental findings53,54. This highly tunable filling dependence of the SC domes under the influence of an electric field is caused by modifications in the low-energy bandstructure of MATTG76 and hence the spin-fluctuation spectrum. As depicted in Fig. 1e, f, FM, semi-metallic, or metallic states move to the electron side at ν = + 2, + 3, and the vacated phase space in between is taken over by SC domes driven by AFM fluctuations in the paramagnetic phase. We relate these findings to those of the experimental reports53,54 in more detail in the “Discussion” section below.

Nematic SC order

Next, we analyze the nature of the SC spin-singlet order parameter \(\hat{{{\Delta }}}\) that is obtained from our atomistic BCS theory for unconventional superconductivity (see “Methods” section for details). We concentrate on U = 5.1 eV, T = 0.2 K and ν = −2.5, firmly placing the system in an SC state. Here the SC order shows clear nematic signatures of C3z-symmetry breaking on the atomic (carbon-carbon) bond scale and the moiré length scale, see Fig. 2a, b. First, the spatially resolved order parameter amplitude ∣Δ(ri)∣ obtained from averaging the order field \(\hat{{{\Delta }}}={{{\Delta }}}_{ij}\) over nearest-neighbor bonds, and shown in Fig. 2a, depicts clear signatures of C3z symmetry breaking on the moiré scale. The nematic SC ground-state is threefold degenerate consisting of three order parameters with nematic axis C2 varying by rotation around 120°. All three states are degenerate in free energy, thus breaking the original C3z symmetry of the Hamiltonian spontaneously. Furthermore, we find that the order parameter is completely real-valued and thus restores time-reversal symmetry in contrast to any chiral \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\pm i{d}_{xy}\) SC state. In fact, we find that complex–linear combinations of the d-wave components \({{{\Delta }}}_{ij}=\cos (\theta ){f}_{{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}}^{ij}+\sin (\theta ){e}^{i\phi }{f}_{{d}_{xy}}^{ij}\) are energetically disfavored [see Fig. 2e]. The amplitude distribution of the order parameter is strongly enhanced in the AAA regions along the nematic C2 axis in the middle layer of MATTG and is a factor of ~10 smaller in the outer two layers as depicted in Fig. 2a. At the same time, the order parameter vanishes in the ABA and BAB regions as expected due to the lack of states in the non-interacting Hamiltonian.

a Spatially resolved atomistic gap \(| {{\Delta }}({{{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}}}_{i})| /\max \{| {{\Delta }}({{{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}}}_{i})| \}\) in the outer layer of MATTG. Our analysis reveals three degenerate real-valued ground states that break C3z rotational symmetry on the moiré scale along the nematic axis C2 (black arrow). b Layer-wise representation of the order parameter field. The value of ∣Δ(ri)∣ is larger by a factor of ~10 in the middle layer compared to the outer layers with most weight being concentrated in the AAA regions. The phase of the superconducting gap is shifted by π between single layers. Additionally to the nematicity on the moiré scale, we find strong local atomic-scale nematicity in the orientation of the d-wave components τ(ri) (black streamlines). The moiré nematicity is clearly visible due to the emergence of a vortex–antivortex pattern near the AAA regions. c Local density of states (LDOS) in the superconducting state \({\hat{{{\Delta }}}}_{3}\) from a in the AAA region of the outer layer of MATTG. Peaks at selected energies (1)–(4), which correspond to flat bands being gapped by the order parameter, show clear signatures of C3z symmetry breaking. In subpanel (2), the influence of the C2 nematic axis is visible: for low energies, quasiparticles are forbidden to occupy the AAA regions along the direction of C2 due to the presence of the superconducting condensate but accumulate on both sides where the gap amplitude vanishes. This leads to a strong degree of C3z symmetry breaking as visualized by the color code in the main panel. d Strength of the superconducting order and its projections on the honeycomb d-wave components as a function of the Hubbard-U. The d-wave order parameter increases exponentially as a function of interaction strength U. The s+ projection has negligible weight. e Free energy of all complex superpositions of the real-valued irreducible representations dxy and \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\). The minima in free energy occur for the real-valued nematic solutions (and their U(1) transformations) only.

In addition, we characterize the SC order parameter on the atomic scale, where the symmetry is given by the D6h point group of the single graphene sheets. As the FLEX pairing vertex \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\) is most attractive on nearest-neighbor bonds, we project the gap onto the complete basis set fη spanned by the irreducible representations of D6h, which consists of the extended s-wave η = s+ and two d-wave components dxy and \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\), see “Methods.” Our analysis reveals that the real-valued order parameter shows nematic d-wave characteristics with vanishing s-wave amplitude, similar to atomistic calculations in MATBG7,85. To this end, we define a real-valued two-component vector for each carbon atom \({{{{{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}}}}({{{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}}}_{i})={\sum }_{j}{{{\Delta }}}_{ij}{({f}_{{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}}^{ij},{f}_{{d}_{xy}}^{ij})}^{{{{{{\rm{T}}}}}}}\) that captures the spatially varying orientation in the d-wave components and is displayed as streamlines in Fig. 2b. There exists a local d-wave nematicity on the carbon-carbon bond scale that forms a vortex-antivortex structure close to the AAA and ABA/BAB regions and is aligned to the C2 nematic axis on the moiré scale. Interestingly, the phase of τi from the middle to the outer layers of MATTG is shifted by π, which is a consequence of the interlayer repulsion in the normal-state Hamiltonian. This π-locked Josephson coupling was previously also observed between the two graphene sheets in MATBG and is expected to stabilize the nematic phase7,85.

The averaged amplitude of the nematic SC order parameter \(| \bar{{{\Delta }}}| =\langle | {{\Delta }}({{{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}}}_{i})| \rangle\) is sensitive to the choice of the Hubbard-U with respect to the critical interaction strength Uc predicted by the RPA analysis. In Fig. 2d, we show that for ν = −2.5 and T = 0.2 K nematic superconductivity is only present if U − Uc ≲ 0.1 eV in our approximation. Approaching the magnetic instability U → Uc, the overall amplitude of the pairing interaction \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\) increases and the gap parameter grows exponentially as a function of interaction strength and density of states ρ(ϵ) on the Fermi surface \(\propto \exp \left[-1/(\rho ({E}_{F})| {\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}| )\right]\) as expected in a weak-coupling theory. This also emphasizes the sensitivity of superconductivity to screening the interactions or to changes in the spin-fluctuation spectrum, as for example by a displacement field as demonstrated in Fig. 1e, f.

The nematic properties of the SC state lead to clear signatures of C3z-symmetry breaking in the LDOS. Figure 2c depicts the LDOS at the AAA region in the outer layer of MATTG. We find that the SC state gaps the flat bands in MATTG, while the highly dispersive Dirac cone remains partially ungapped (within the energy resolution 0.01 meV of our calculations) as each Dirac cone shows two nodes on the Fermi surface, see Fig. 3. For low energies E ≲ ∣Δ∣, quasi particle excitations are forbidden in the AAA regions along the nematic axis C2 due to the large gap amplitude in the SC condensate as shown in the subpanel (2) of Fig. 2c. For larger energies [subpanels (1), (3), (4)] the system continuously goes back to a spectral weight distribution similar to the normal-state Hamiltonian shown in Fig. 1 with a lower degree of C3z symmetry breaking. To analyze the behavior of the Dirac cone and the flat bands in more detail, in Fig. 3a we show the density of states (DOS) in the SC phase either for the full system (black thick line) and restricted to the central layer (thin gray line). In the BCS formalism, condensation of Cooper pairs occurs on the energy scale of \(| \bar{{{\Delta }}}|\), whereas electronic excitations are described in terms of fermionic quasiparticles with energy \(\pm {E}_{n,{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}\approx \pm \sqrt{{({\epsilon }_{n,{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}-\mu )}^{2}+| {{{\Delta }}}_{n,{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}{| }^{2}}\) that are shifted relative to the energies in the normal state ϵn,k by the order parameter amplitude (in momentum-band space) ∣Δn,k∣, resulting in a particle-hole symmetric DOS. In the DOS of all layers, we find separate features of the Dirac cone (highlighted by the red line) and the flat bands. While the flat bands are fully-gapped (black line), the Dirac cone remains partially ungapped and leads to separate linear signatures ~∣E∣ (red line).

a The density of states in the superconducting state captures fermionic quasiparticle excitations with energies \(\pm {E}_{n,{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}\approx \pm \sqrt{{({\epsilon }_{n,{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}-\mu )}^{2}+| {{{\Delta }}}_{n,{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}{| }^{2}}\) that result in the DOS being particle-hole (ph) symmetric. In the DOS of all layers (black line), we find clear and separate features of the Dirac cone (highlighted by the red line) and the flat bands: While the flat bands are fully gapped on an energy scale of ~1 meV (black line), the Dirac cone leads to separate linear signatures ~∣E∣ (green dashed line) in the DOS. The partial DOS of the middle layer of MATTG (gray line) shows no contribution from the Dirac cone’s DOS ~∣E∣ but contains contributions of the flat bands only. This is in agreement with the Dirac cone having dominant spectral weight in the outer layers, whereas the flat bands dominate in the middle layer. b, c Quasiparticle energy landscape E(k) as a function of momentum in the Brillouin zone of MATTG. In the superconducting phase, the Dirac cones at K and \({K}^{\prime}\) each show two nodes in the quasiparticle spectrum reflecting the C3z symmetry breaking nature of the nematic superconducting phase in momentum space. These nodes become distinguishable by the dark blue regions in c indicating the vanishing gap amplitude ∣Δn,k∣ → 0 as the quasiparticle energies approach E(k) → 0. d Schematic sketch of the Dirac cone in the normal state (upper panel) and superconducting phase (lower panel). In the non-interacting case \(\hat{{{\Delta }}}=0\) and at filling ν = −2.5, the chemical potential (yellow plane) cuts the Dirac cone at energies higher than the Dirac point such that the tip of the Dirac cone is mirrored by ph-symmetry and the Fermi surface consists of a ring (black line). In the superconducting phase, the quasiparticle spectrum shows two nodes at this Fermi surface (green arrows) but is gapped away from these points.

First, the flat bands of MATTG are fully gapped on an energy scale of ~1 meV (black line) corresponding to the average gap amplitude \(| \bar{{{\Delta }}}|\). Although the gap can reach values of 10 meV in the AAA regions where it is strongly amplified, the DOS is sensitive only to the spatially averaged value of the gap. Comparing this to the density of states of only the middle layer (thin gray line) illustrates that the Dirac cone has dominant weight on the outer layers only: the linear contribution to the density of states of all layers is not present in the central layer and a true gap of ~1 meV opens up. This shows that the dominant contribution to the flat bands resides in the central layer.

Next, we analyze the band splitting of the Dirac cones by calculating the quasiparticle spectrum E(k) throughout the Brillouin zone (BZ) of MATTG, see Fig. 3b. The Dirac cones located at K and \({K}^{\prime}\) each show two nodes in the quasiparticle spectrum that reflect the C3z symmetry breaking of the nematic SC state in momentum space. In Fig. 3c, these nodes become visible by the dark blue regions indicating the vanishing gap amplitude \(| \bar{{{\Delta }}}| \to 0\) as the quasiparticle energies approach E(k) → 0. In Fig. 3d, we sketch the situation close to the Dirac cone for the chosen filling of ν = −2.5. The chemical potential (yellow plane) cuts the Dirac cone at energies higher than the one of the Dirac point such that the tip of the Dirac Cone is mirrored due to the particle-hole symmetry of the quasiparticle spectrum and the Fermi surface consists of a ring (black line). In the SC phase, the particle-hole symmetric quasiparticle spectrum shows two nodes on this Fermi surface [green arrows in Fig. 3d]. Away from these nodes, the Dirac cone is slightly gapped. Collectively, this leads to a linearly increasing DOS around the Fermi-level, in contrast to the constant contributions that would be present if the Dirac Cones remained completely ungapped.

Since the flat bands (Dirac Cone) can be labeled according to the symmetric (anti-symmetric) irreducible representation of the mirror reflection symmetry σh, the different contributions to the DOS suggest that superconductivity in MATTG is mainly driven by the flat bands, whereas superconductivity in the Dirac Cone is only induced by proximity to the flat bands. This is also reflected in the real-space properties of the order parameter \(\hat{{{\Delta }}}\). Since the Dirac Cone belongs to the anti-symmetric irreducible representation it only has spectral weight on the outer layers (l = 1, 3), where superconductivity is significantly suppressed relative to the middle layer. Meanwhile, the SC state is fully gapped in the central layer, which must originate from the flat bands. We hence argue that quasiparticle excitations in the Dirac Cone are only possible due to proximity to the flat bands.

Discussion

Our work emphasizes the role of spin-fluctuation exchange in the formation of SC instabilities in MATTG. By including both long-ranged (Hartree) and short-ranged (Hubbard-U) electron–electron interactions in our microscopic theory, we find that without a displacement field, FM ordering dominates around integer fillings ν = −3, −2, −1 and 1 even at relatively small interaction strengths (U ≈ 3–4 eV). In between these integer fillings stabilizing AFM order requires a larger interaction strength (U ≈ 4–5 eV). Intriguingly, estimating U from the monolayer graphene case puts the interaction strength right at the border of these different ordering tendencies. This allows superconductivity mediated by spin fluctuations in between integer fillings for values smaller than the critical interaction required to stabilize AFM order. This superconductivity is bounded by the above-mentioned stronger FM order when approaching integer fillings, naturally restricting the region of superconductivity to dome structures in a ν–T phase diagram.

At zero electrical field, choosing e.g. U = 5.1 eV, we find the strongest superconductivity for fillings between ν = −3 and ν = −2 caused by low-energy AFM spin-fluctuations in the paramagnetic phase. In this regime, superconductivity occurs within a characteristic dome shape in the ν–T phase diagram exhibiting a critical temperature of Tc ≈ 2 K. This is also where refs. 53,54 find clear signatures of an SC state. A weaker SC feature is predicted around ν = + 2, which, however, within our approach is not surrounded by FM order. In ref. 53 superconductivity was reported at a similar filling, while ref. 54 only finds very weak indications of superconductivity around that filling without displacement field.

Including a displacement field, FM order is weakened at the hole side and strengthened at the electron side at least for integer fillings of ν = +2 and +3, which we attribute to dramatic changes in the spin-fluctuation spectrum. Superconductivity is strengthened in between these fillings in agreement with ref. 54. The additional SC features, which appear only in ref. 53 at fillings between ν = +1 and +2 and in between ν = −1 and −2 deserve further study. At values of U for which we can robustly argue for superconductivity between ν = ±2 and ±3, AFM order has already taken over at filling between ν = ±1 and ±2. This might hint towards an insufficiency of our mean-field approach, overestimating the strength of AFM order due to the absence of quantum fluctuations and neglecting interchannel feedback. From a methodological point of view, it would be conducive to study MATTG using unbiased methods like the functional renormalization group or tensor product states, although this may require a fundamental advance to numerically treat the large moiré unit cell without restricting the analysis to the low-energy bands.

As next steps, we suggest the experimental scrutiny of (i) the filling dependence of the SC phase when tuning the electronic interactions by screening32 and of (ii) the emergent nematicity. The latter should yield clear signatures of C3z-symmetry breaking in the LDOS being accessible within STM measurements. Since recent experimental work55 suggests that the SC phase might be of non-spin-singlet type close to the filling ν = −2.4, this also deserves further theoretical investigation in our approach as FM spin-fluctuations, which surround the SC dome in our phase diagram, are known to drive spin-triplet SC phases86. Revealing the intrinsic interplay between spin-singlet and spin-triplet phases is an exciting avenue of future research.

Methods

Moiré structure

The commensurate moiré unit cell of twisted trilayer graphene (TTG) can be defined using the same convention as twisted bilayer graphene (TBG)77. We start from perfectly aligned, AAA stacked trilayer graphene with a carbon atom of each layer residing at the origin of the x–y plane, and twist the middle layer anti-clockwise with respect to the encapsulating layers about the z-axis. This creates a structure with a single moiré pattern because of the alignment of the encapsulating layers.

For atomistic methods, commensurate moiré unit cells must be constructed. Following ref. 77, commensurate moiré structures are defined by two integers n and m, which specify the twist angle, θ, via

The corresponding triangular moié lattice has a length scale that is determined through the twist angle via

where a0 is the lattice constant of graphene. For our simulations, we use n, m = 20, 21 (θ = 1.61°), which leads to a commensurate unit cell of size L(θ) = 8.59 nm that contains N = 7566 carbon sites.

We relax the atomic positions of TTG using classical force fields implemented in LAMMPS87. For the intralayer potential, we use AIREBO-morse88, and for the interlayer potential, we use Kolmogorov–Crespi potential89. We take the lattice parameter of graphene to be a0 = 2.42 Å.

Atomistic modeling and Hartree calculations

In real space, the atomistic TB Hamiltonian takes the form

The operator \({c}_{i\sigma }^{({{\dagger}} )}\) annihilates (creates) an electron at site ri with spin σ. The pz electrons are coupled via Slater-Koster hopping parameters77:

Here ez is a unit vector that points perpendicular to the graphene sheets, d0 = 1.362 a0 is the vertical spacing of graphite, δ0 = 0.184 a0 is the transfer integral decay length, and \({a}_{{{{{{\rm{cc}}}}}}}={a}_{0}/\sqrt{3}\) is the distance between two nearest neighboring carbon atoms (in pristine graphene). The term Vppσ = 0.48 eV describes the interlayer hopping while Vppπ = −2.7 eV models the intralayer hopping.

To obtain good agreement with DFT calculations for the electronic structure at charge neutrality, we add an additional onsite energy term through

where this term only exists on the inner, twisted layer (2), as indicated by the subscript of the Hamiltonian.

We performed self-consistent Hartree TB calculations following the method outlined in ref. 80. Full details of the method have been outlined in the Supplementary Methods for completeness. We utilize a 8 × 8 regular grid in the BZ to calculate the electron density and a 11 × 11 set of moiré unit cells to converge the Hartree potential in real space. An on-site interaction of 17 eV is used with a 1/∣r∣ potential with a dielectric constant of 1 for all other interactions. We work in the limit of zero temperature and employ a linear mixing scheme to iteratively converge the set of equations.

The full TB Hamiltonian consists of the following contributions

The hopping terms are included through \({\hat{H}}^{0}\), Hartree interactions are included through \({\hat{H}}^{H}\), the additional onsite potential energy is included through \({\hat{H}}^{{{\Delta }}}\), and finally an electric field is included through \({\hat{H}}^{E}\). Further details of the Hartree contributions and the inclusion of the electric field can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Density functional theory

DFT calculations were carried out using ONETEP90 on large twist angle TTG structures, see Supplementary Methods for results. We utilized the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange–correlation functional91 with projector-augmented-wave pseudopotentials92, a kinetic energy cutoff of 800 eV, and a minimal basis of four non-orthogonal generalized Wannier functions per carbon atom. Due to the metallic nature of TTG, we use the ensemble-DFT approach93. Our calculations are converged such that the total energy change between iterations is <25 meV.

Magnetic susceptibility

To account for magnetic fluctuations, we add a Hubbard interaction acting on the graphene pz orbitals in the Hamiltonian \({\mathsf{H}}\) :

To treat the four-fermion term \({\mathsf{H}}^{{{\rm{I}}}}\), we employ the RPA in the static, long-wavelength limit q = (q, q0) → 0 as presented in ref. 9. To this end, we calculate the atomistic magnetic susceptibility \({\hat{\chi }}_{0}\):

The Green’s function \(\hat{G}({{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}},{k}_{0})={G}_{ij}({{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}},{k}_{0})\) as a function of Matsubara frequency k0, moiré momentum k is given by

with \(\hat{H}({{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}})\) the “non-interacting” TB Hamiltonian including the Hartree corrections and μ is the chemical potential corresponding to the filling factor used in the Hartree potential.

We find that the critical Hubbard-U needed for the onset of magnetic ordering is given by Uc = −1/λ0, with λ0 being the lowest eigenvalue of \({\hat{\chi }}_{0}\). The magnetic ordering is proportional to the corresponding eigenvector \({\overrightarrow{v}}_{0}\). For numerical evaluation of the Matsubara sum in Eq. (8), we use the exact same frequency grid presented in ref. 8 and thus are able to take into account the effect of low-temperature instabilities. We sample the moiré BZ with Nk = 24 points for the RPA simulations.

Fluctuation–exchange approximation

To account for pairing instabilities mediated by charge- and spin-fluctuation exchange, we derive a microscopic pairing interaction \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\) in the FLEX that incorporates effects of transverse and longitudinal spin-fluctuations. In terms of the full atomistic RPA susceptibility \({\hat{\chi }}_{0}\), the scattering between Cooper pairs in the singlet channel is described by the pairing vertex81

For diagrammatic details on the derivation of the FLEX pairing vertex, the reader may refer to the Supplementary Methods. In the static, long-wavelength limit q = (q, q0) → 0, the spatial profile of the long-ranged interaction vertex strongly depends on the magnetic fluctuations predicted by the RPA analysis, see Supplementary Methods. The latter limit proves to contain the relevant physics when starting with local repulsive interactions. The RPA susceptibility \({\hat{\chi }}_{0}\) predicts spin correlations at length scales intermediate to the carbon–carbon bond scale and moiré length scale, thus being described by orderings at q = 0. The system hence shows the same ordering tendencies in all moiré unit cells with variable correlations present on the carbon-carbon bond scale.

SC state

To analyze the SC properties of the system, we decouple the effective pairing vertex \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\) in mean-field approximation, allowing only for symmetric spin-singlet bond order parameters Δij = Δji due to the proximity to AFM tendencies in between the integer fillings

The resulting mean-field Hamiltonian can be rewritten in the Nambu spinor basis \({\psi }_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}^{{{\dagger}} }={({\overrightarrow{c}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}\uparrow }{\overrightarrow{c}}_{-{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}\downarrow }^{{{\dagger}} })}^{{{{{{\rm{T}}}}}}}.\) The full 2N-dimensional Hamiltonian for the spin-dependent pz orbitals of the carbon atoms is of BdG form

The BdG bilinear form is diagonalized by a block-structured unitary transform \({\hat{U}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}\)

The matrices \({\hat{u}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}\left({\hat{v}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}}\right)\) are N × N matrices, which describe the particle (hole) amplitudes of the fermionic Bogoliubov quasiparticles γk with energies ±Ek. The latter are defined as

Together with Eq. (11), this yields a set of non-linear equations that needs to be solved self-consistently:

To this end, we start with an initial guess \({{{\Delta }}}_{ij}^{\,{{\mbox{init}}}\,}\) and iterate until convergence is achieved using a linear mixing \({\hat{{{\Delta }}}}^{n+1}=(1-\alpha ){\hat{{{\Delta }}}}^{n}-\alpha {\hat{{{\Delta }}}}^{n-1}\) scheme to avoid bipartite solutions in the fixed point iteration. In all of our calculations, we set the relative error for convergence of \(\hat{{{\Delta }}}\) to ϵ = 10−6 and set the mixing parameter to α = 0.2. Here, we only account for the gap parameter \(\hat{{{\Delta }}}\) at the Γ-point of the BZ. This approximation may not change the underlying physics significantly as our microscopic interaction \({\hat{{{\Gamma }}}}_{2}\) in the static, long-wavelength limit (q → 0) carries no momentum dependence and the size of the BZ of MATTG is drastically reduced due to the large real-space unit cell. Still, we checked that our results do not change qualitatively when taking a dense mesh with up to 24 k-points in the BZ into account. Furthermore, we track the free energy F of the system for different initial guesses and during each self-consistency run to ensure proper convergence of the BdG algorithm, see Supplementary Methods.

To determine the local amplitude of the SC state from the bond-related order field \(\hat{{{\Delta }}}={{{\Delta }}}_{ij}\), we introduce a three-dimensional vector \(\overrightarrow{{{\Delta }}}({{{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}}}_{i})={({{{\Delta }}}_{i,i+{{{{{{\boldsymbol{\delta }}}}}}}_{1}},{{{\Delta }}}_{i,i+{{{{{{\boldsymbol{\delta }}}}}}}_{2}},{{{\Delta }}}_{i,i+{{{{{{\boldsymbol{\delta }}}}}}}_{3}})}^{{{{{{\rm{T}}}}}}}\) that contains the SC bonds to all (three) neighboring sites of the carbon atom located at ri. The norm of this order parameter field yields the lattice-resolved amplitude ∣Δ(ri)∣, whereas the overall amplitude \(| \bar{{{\Delta }}}| =\langle | {{\Delta }}({{{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}}}_{i})| \rangle\) follows from averaging this quantity over all sites in the moiré unit cell. Here, we only take the l = 1, 2, 3 nearest neighbor carbon-carbon bonds δl into account. This is equivalent to considering all SC bonds \(| \bar{{{\Delta }}}| \approx | | \hat{{{\Delta }}}| |\) as nearest-neighbor sites are strongly favored in terms of attractive interaction generated by the spin-fluctuations exchange mechanism, see Supplementary Methods.

Symmetry classification of the gap parameter and LDOS

To characterize the SC order parameter with respect to different pairing channels on the atomic carbon–carbon bond scale, we project the order parameter onto the complete basis set formed by the irreducible representations of the D6h point group

where η denotes different spin-singlet pairing channels: the extended s-wave s+ and two d-wave components dxy and \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\). The coefficients fη(δl) are form factors that correspond to the pairing channel and are obtained by symmetrizing the bond functions δl with the irreducible representations of the point group D6h of graphene. The form factors are: \({s}^{+}=(1,1,1)/\sqrt{3}\), \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}=(2,-1,-1)/\sqrt{6}\) and \({d}_{xy}=(0,1,-1)/\sqrt{2}\). Here, we only take the l = 1, 2, 3 nearest neighbor carbon-carbon bonds δl into account, as they are dominant in terms of attractive interaction strength, see Supplementary Methods. The LDOS in the SC phase is given by

To this end, we assume that the gap does not change significantly when calculated at different points in the (mini)-BZ such that \(\hat{{{\Delta }}}({{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}})\approx \hat{{{\Delta }}}({{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}}=0)\). Applying this Γ-point approximation, we diagonalize the Nambu Hamiltonian Eq. (12) for up to 100 × 100 points in the BZ of MATTG. To speed up the convergence, we use an adaptive momentum mesh that allows for finer sampling around the K and \({K}^{\prime}\) points. The δ-function in Eq. (17) is approximated by a Lorentzian kernel with broadening η = 0.03 meV. The DOS is obtained from the LDOS by adding up the contribution of all sites. To capture the degree of C3z symmetry breaking in the LDOS in the nematic SC phase, we compute the energy-resolved anisotropy \({\zeta }^{{C}_{3z}}(E)\) by comparing the LDOS at each site \(\overrightarrow{\rho }(E)\) with its counterpart Rφρi(E) resulting from rotation around φ ∈ {120°, 240°}:

Note that the nematic SC order parameter breaks C3z symmetry on the microscopic (graphene) sub-lattice and moiré scale. Since the latter is easier to access experimentally, we smear the LDOS in real space with a Gaussian envelope of width σ = a0 such that \({\zeta }^{{C}_{3z}}(E)\) only captures the degree of C3z symmetry breaking on the moiré scale.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Simulation codes are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80–84 (2018).

Kennes, D. M. et al. Moiré heterostructures: a condensed matter quantum simulator. Nat. Phys. 17, 155–163 (2021).

Carr, S. et al. Twistronics: manipulating the electronic properties of two-dimensional layered structures through their twist angle. Phys. Rev. B 95, 075420 (2017).

Guinea, F. & Walet, N. R. Electrostatic effects, band distortions, and superconductivity in twisted graphene bilayers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 13174–13179 (2018).

Kennes, D. M., Lischner, J. & Karrasch, C. Strong correlations and d+id superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 98, 241407(R) (2018).

Fischer, A., Klebl, L., Honerkamp, C. & Kennes, D. M. Spin-fluctuation-induced pairing in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 103, L041103 (2021).

Klebl, L., Goodwin, Z. A. H., Mostofi, A. A., Kennes, D. M. & Lischner, J. Importance of long-ranged electron-electron interactions for the magnetic phase diagram of twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 103, 195127 (2021).

Klebl, L. & Honerkamp, C. Inherited and flatband-induced ordering in twisted graphene bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 100, 155145 (2019).

Gonzalez-Arraga, L. A., Lado, J. L., Guinea, F. & San-Jose, P. Electrically controllable magnetism in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 107201 (2017).

Xie, M. & MacDonald, A. H. On the nature of the correlated insulator states in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 097601 (2020).

González, J. & Stauber, T. Kohn-luttinger superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 026801 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Jiang, K., Wang, Z. & Zhang, F. Correlated insulating phases of twisted bilayer graphene at commensurate filling fractions: a Hartree-Fock study. Phys. Rev. B 102, 035136 (2020).

Goodwin, Z. A. H., Corsetti, F., Mostofi, A. A. & Lischner, J. Attractive electron-electron interactions from internal screening in magic angle twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 100, 235424 (2019).

González, J. & Stauber, T. Time-reversal symmetry breaking versus chiral symmetry breaking in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 102, 081118(R) (2020).

Cea, T. & Guinea, F. Band structure and insulating states driven by coulomb interaction in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 102, 045107 (2020).

Klebl, L., Kennes, D. M. & Honerkamp, C. Functional renormalization group for a large moiré unit cell. Phys. Rev. B 102, 085109 (2020).

Yan, X., Law, X. K. T. & Lee, P. A. Kekulé valence bond order in an extended Hubbard model on the honeycomb lattice with possible applications to twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 98, 121406(R) (2018).

Wu, F., MacDonald, A. H. & Martin, I. Theory of phonon-mediated superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 257001 (2018).

Choi, Y. W. & Choi, H. J. Strong electron-phonon coupling, electron-hole asymmetry, and nonadiabaticity in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 98, 241412(R) (2018).

Padhi, B., Setty, C. & Phillips, P. W. Doped twisted bilayer graphene near magic angles: Proximity to wigner crystallization, not mott insulation. Nano Lett. 18, 6175–6180 (2018).

Yu, T., Kennes, D. M., Rubio, A. & Sentef, M. A. Nematicity arising from a chiral superconducting ground state in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene under in-plane magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 127001 (2021). Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01426.

Samajdar, R. et al. Electric-field-tunable electronic nematic order in twisted double-bilayer graphene. 2D Mater. 8, 034005 (2021). Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.08385.

Qin, W., Zou, B. & MacDonald, A. H. Critical magnetic fields and electron-pairing in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.10504 (2021).

Lin, Y.-P. & Nandkishore, R. M. Chiral twist on the high-Tc phase diagram in moiré heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 100, 085136 (2019).

Lin, Y.-P. & Nandkishore, R. M. Parquet renormalization group analysis of weak-coupling instabilities with multiple high-order van hove points inside the Brillouin zone. Phys. Rev. B 102, 245122 (2020).

Lu, X. et al. Superconductors, orbital magnets and correlated states in magic-angle bilayer graphene. Nature 574, 653–657 (2019).

Cao, Y. et al. Strange metal in magic-angle graphene with near planckian dissipation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 076801 (2020).

Polshyn, H. et al. Large linear-in-temperature resistivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 15, 1011–1016 (2019).

Yankowitz, M. et al. Tuning superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 363, 1059–1064 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Tuning electron correlation in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene using coulomb screening. Science 371, 1261–1265 (2021).

Stepanov, P. et al. Untying the insulating and superconducting orders in magic-angle graphene. Nature 583, 375–378 (2020).

Saito, Y., Ge, J., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Young, A. F. Independent superconductors and correlated insulators in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 926–930 (2020).

Das, I. et al. Symmetry-broken chern insulators and rashba-like landau-level crossings in magic-angle bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 17, 710–714 (2021).

Wu, S., Zhang, Z., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Andrei, E. Y. Chern insulators, van hove singularities and topological flat bands in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Mater. 20, 488–494 (2021).

Nuckolls, K. P. et al. Strongly correlated chern insulators in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 588, 610–615 (2020).

Arora, H. S. et al. Superconductivity in metallic twisted bilayer graphene stabilized by wse 2. Nature 583, 379–384 (2020).

Serlin, M. et al. Intrinsic quantized anomalous hall effect in a moiré heterostructure. Science 367, 900–903 (2020).

Sharpe, A. L. et al. Emergent ferromagnetism near three-quarters filling in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 365, 605–608 (2019).

Zondiner, U. et al. Cascade of phase transitions and dirac revivals in magic-angle graphene. Nature 582, 203–208 (2020).

Wong, D. et al. Cascade of electronic transitions in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 582, 198–202 (2020).

Xie, Y. et al. Spectroscopic signatures of many-body correlations in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 572, 101–105 (2019).

Kerelsky, A. et al. Maximized electron interactions at the magic angle in twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 572, 95–100 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. Charge order and broken rotational symmetry in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 573, 91–95 (2019).

Choi, Y. et al. Electronic correlations in twisted bilayer graphene near the magic angle. Nat. Phys. 15, 1174–1180 (2019).

Cao, Y. et al. Nematicity and competing orders in superconducting magic-angle graphene. Science 372, 264–271 (2021).

Carr, S., Fang, S. & Kaxiras, E. Electronic-structure methods for twisted moiré layers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 748–763 (2020).

Balents, L., Dean, C. R., Efetov, D. K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity and strong correlations in moiré flat bands. Nat. Phys. 16, 725–733 (2020).

Burg, G. W. et al. Correlated insulating states in twisted double bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 197702 (2019).

Shen, C. et al. Correlated states in twisted double bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 520–525 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Tunable spin-polarized correlated states in twisted double bilayer graphene. Nature 583, 221–225 (2020).

Rubio-Verdú, C. et al. Universal moiré nematic phase in twisted graphitic systems. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.11645 (2020).

Park, J. M., Cao, Y., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Tunable strongly coupled superconductivity in magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene. Nature 590, 249–255 (2021).

Hao, Z. et al. Electric field–tunable superconductivity in alternating-twist magic-angle trilayer graphene. Science 371, 1133–1138 (2021).

Cao, Y., Park, J. M., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Pauli-limit violation and re-entrant superconductivity in moiré graphene. Nature 595, 526–531 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Correlated insulating states and transport signature of superconductivity in twisted trilayer graphene superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 166802 (2021).

Shi, Y. et al. Tunable van hove singularities and correlated states in twisted trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 17, 619–626 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Correlated electronic phases in twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 19, 861–866 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Simulation of Hubbard model physics in wse2/ws2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 353–358 (2020).

Xian, L. et al. Realization of nearly dispersionless bands with strong orbital anisotropy from destructive interference in twisted bilayer mos2. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–9 (2021).

Regan, E. C. et al. Mott and generalized wigner crystal states in wse2/ws2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 359–363 (2020).

Vitale, V., Atalar, K., Mostofi, A. A. & Lischner, J. Flat band properties of twisted transition metal dichalcogenide homo- and heterobilayers of mos2, mose2, ws2 and wse2. 2D Mater. 8, 045010 (2021). Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.03259.

Xian, L., Kennes, D. M., Tancogne-Dejean, N., Altarelli, M. & Rubio, A. Multiflat bands and strong correlations in twisted bilayer boron nitride: doping-induced correlated insulator and superconductor. Nano Lett. 19, 4934–4940 (2019).

Ni, G. X. et al. Soliton superlattices in twisted hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 10, 4360 (2019).

Kennes, D. M., Xian, L., Claassen, M. & Rubio, A. One-dimensional flat bands in twisted bilayer germanium selenide. Nat. Commun. 11, 1124 (2020).

Carr, S., Fang, S., Jarillo-Herrero, P. & Kaxiras, E. Pressure dependence of the magic twist angle in graphene superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085144 (2018).

Goodwin, Z. A. H. et al. Critical role of device geometry for the phase diagram of twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 101, 165110 (2020).

Bistritzer, R. & MacDonald, A. H. Moiré bands in twisted double-layer graphene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12233–12237 (2011).

Dos Santos, J. L., Peres, N. & Neto, A. C. Graphene bilayer with a twist: electronic structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 256802 (2007).

Shallcross, S., Sharma, S., Kandelaki, E. & Pankratov, O. Electronic structure of turbostratic graphene. Phys. Rev. B 81, 165105 (2010).

Morell, E. S., Correa, J., Vargas, P., Pacheco, M. & Barticevic, Z. Flat bands in slightly twisted bilayer graphene: tight-binding calculations. Phys. Rev. B 82, 121407 (2010).

Kang, J. & Vafek, O. Strong coupling phases of partially filled twisted bilayer graphene narrow bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 246401 (2019).

Park, J. M., Cao, Y., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Flavour Hund’s coupling, correlated chern gaps, and diffusivity in moiré flat bands. Nature 592, 43–48 (2021). Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.12296.

Chen, G. et al. Signatures of tunable superconductivity in a trilayer graphene moiré superlattice. Nature 572, 215–219 (2019).

Carr, S. et al. Ultraheavy and ultrarelativistic dirac quasiparticles in sandwiched graphenes. Nano Lett. 20, 3030–3038 (2020).

Lopez-Bezanilla, A. & Lado, J. L. Electrical band flattening, valley flux, and superconductivity in twisted trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033357 (2020).

Trambly de Laissardière, G., Mayou, D. & Magaud, L. Localization of dirac electrons in rotated graphene bilayers. Nano Lett. 10, 804–808 (2010).

Zhu, Z., Carr, S., Massatt, D., Luskin, M. & Kaxiras, E. Twisted trilayer graphene: A precisely tunable platform for correlated electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 116404 (2020).

Khalaf, E., Kruchkov, A. J., Tarnopolsky, G. & Vishwanath, A. Magic angle hierarchy in twisted graphene multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 100, 085109 (2019).

Goodwin, Z. A., Vitale, V., Liang, X., Mostofi, A. A. & Lischner, J. Hartree theory calculations of quasiparticle properties in twisted bilayer graphene. Electron. Struct. 2, 034001 (2020).

Berk, N. F. & Schrieffer, J. R. Effect of ferromagnetic spin correlations on superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 17, 433–435 (1966).

Pizarro, J. M., Rösner, M., Thomale, R., Valentí, R. & Wehling, T. O. Internal screening and dielectric engineering in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 100, 161102 (2019).

Schüler, M., Rösner, M., Wehling, T. O., Lichtenstein, A. I. & Katsnelson, M. I. Optimal Hubbard models for materials with nonlocal coulomb interactions: graphene, silicene, and benzene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 036601 (2013).

Wehling, T. O. et al. Strength of effective coulomb interactions in graphene and graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 236805 (2011).

Löthman, T., Schmidt, J., Parhizgar, F. & Black-Schaffer, A. M. Nematic superconductivity in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene from atomistic modeling. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.11555 (2021).

Ran, S. et al. Nearly ferromagnetic spin-triplet superconductivity. Science 365, 684–687 (2019).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comp. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

O’Connor, T. C., Andzelm, J. & Robbins, M. O. Airebo-m: a reactive model for hydrocarbons at extreme pressures. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 024903 (2015).

Kolmogorov, A. N. & Crespi, V. H. Registry-dependent interlayer potential for graphitic systems. Phys. Rev. B 71, 235415 (2005).

Prentice, J. C. At The onetep linear-scaling density functional theory program. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 174111 (2020).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Garrity, K. F., Bennett, J. W., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Pseudopotentials for high-throughput dft calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 81, 446–452 (2014).

Ruiz-Serrano, À. & Skylaris, C.-K. A variational method for density functional theory calculations on metallic systems with thousands of atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 054107 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Vitale for useful discussions on DFT simulations and X. Liang for useful discussions on the relaxations of the system. Z.A.H.G. was supported through a studentship in the Centre for Doctoral Training on Theory and Simulation of Materials at Imperial College London funded by the EPSRC (EP/L015579/1). We acknowledge funding from EPSRC grant EP/S025324/1, support from the Thomas Young Centre under grant number TYC-101, and the Imperial College London Research Computing Service (https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/2232) for computational resources used in carrying out this work. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) is acknowledged for support through RTG 1995, within the Priority Program SPP 2244 2DMP and under Germany’s Excellence Strategy-Cluster of Excellence Matter and Light for Quantum Computing (ML4Q) EXC2004/1 - 390534769. We acknowledge support from the Max Planck-New York City Center for Non-Equilibrium Quantum Phenomena. RPA, BdG, and LDOS calculations were performed with computing resources granted by RWTH Aachen University under projects rwth0589 and rwth0595.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F., Z.A.H.G., and L.K. performed atomistic modeling. D.M.K. and L.K. conceptualized and supervised the project. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fischer, A., Goodwin, Z.A.H., Mostofi, A.A. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-021-00410-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-021-00410-w

This article is cited by

-

Ising superconductivity induced from spin-selective valley symmetry breaking in twisted trilayer graphene

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Advance in two-dimensional twisted moiré materials: Fabrication, properties, and applications

Nano Research (2023)

-

Evidence for unconventional superconductivity in twisted trilayer graphene

Nature (2022)

-

Formation of One-Dimensional van der Waals Heterostructures via Self-Assembly of Blue Phosphorene Nanoribbons to Carbon Nanotubes

Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica (2022)