Abstract

Disorder can have remarkably disparate consequences in superconductors, driving superconductor–insulator transitions in ultrathin films by localizing electron pairs and boosting the supercurrent carrying capacity of thick films by localizing vortices (magnetic flux lines). Though the electronic 3D-to-2D crossover at material thicknesses d ~ ξ (coherence length) is well studied, a similarly consequential magnetic crossover at d ~ Lc (pinning length) that should drastically alter material properties remains largely underexamined. According to collective pinning theory, vortex segments of length Lc bend to adjust to energy wells provided by point defects. Consequently, if d truncates Lc, a change from elastic to rigid vortex dynamics should increase the rate of thermally activated vortex motion S. Here, we characterize the dependence of S on sample thickness in Nb and cuprate films. The results for Nb are consistent with collective pinning theory, whereas creep in the cuprate is strongly influenced by sparse large precipitates. We leverage the sensitivity of S to d to determine the generally unknown scale Lc, establishing a new route for extracting pinning lengths in heterogeneously disordered materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perfect crystallinity is an uncommon material characteristic. For superconductors, it is not only rare, but also often undesirable, as defects are prerequisite for these materials to host high dissipationless currents. This is because disorder can immobilize (pin) vortices, whose motion induces dissipation that adversely affects superconducting properties. Most real materials have heterogeneous defect structures, a preferential feature1,2 to produce high critical current densities Jc because no single defect type is effective at pinning vortices over a wide range of temperatures and magnetic fields. Understanding vortex matter in heterogeneous microstructures poses a tremendous challenge because the effects of combinations of defects are not simply additive, but are often competitive.2,3 Considering systems with only one defect type, a flux line or bundle of lines can be pinned by the collective action of many weak defects (weak collective pinning)4,5 or the independent action of stronger defects.5,6,7 In the former case, individual defects are too weak to pin a vortex, while density fluctuations by ensembles of defects contained within a correlation volume \(V_{\mathrm{c}}\sim R_{\mathrm{c}}^2L_{\mathrm{c}}\) (depicted in Fig. 1) produce a finite pinning force. The volume Vc determines the characteristic pinning energy scale Uc. Because collective pinning theory considers only point defects, it is unclear—and beyond the scope of this theory—how Vc and Uc are affected by even a sparse distribution of larger defects coexisting with point defects.

Correlation volumes in different pinning scenarios. Illustration of pinning volumes for the single vortex, vortex bundle, and mixed pinning regime (from left to right). The volume Vc = \(L_{\mathrm{c}}R_{\mathrm{c}}^2\) (indicated by a dashed ellipsoid) contains many point defects (red) and/or few large inclusions (yellow) and determines the creep rate. The bottom row indicates the situation where Lc is truncated by the sample thickness d. The description of pinning in systems with heterogeneous defects poses an unsolved problem

A further complication to understanding vortex dynamics arises when thermal fluctuations sufficiently energize vortices to overcome the current-dependent activation energy U(J). Vortices then depin (creep) from defects causing the persistent current density to decay logarithmically over time t as J(t) ∝ [1 + (μT/Uc)ln(t/t0)]−1/μ, where 1/t0 is a microscopic attempt frequency and μ > 0 is the glassy exponent.8 This decay defines a creep rate S ≡ −d ln J/d ln t = T/[Uc + μT ln(t/t0)]. With few exceptions, most studies of vortex creep have been performed on single crystals or thick films (e.g., coated conductors with d ≳ 1 μm).9 Yet the broad, often detrimental impact of vortex motion on thin-film-based devices10,11,12 warrants a better understanding of creep in thin films. For sufficiently thin samples, d < Lc, the activation energy and creep rate should acquire an explicit dependence on thickness5,13,14 and the vortex (or bundle) should no longer behave elastically, but rather rigidly. This should produce faster creep.

In this Letter, we present a systematic study of the dependence of the creep rate on film thickness in two very different superconductors: niobium (Nb) and (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x. Niobium is commonly used for device applications, and features a low critical temperature Tc = 9.2 K, moderately large Ginzburg–Landau parameter κ = λ/ξ ~ 11 (our film), and low Ginzburg number9 Gi ~ 10−8. Here, ξ and λ are the in-plane coherence length and penetration depth, respectively. Our film was deposited using DC magnetron sputtering to a thickness of 447 nm, is polycrystalline, and the microstructure includes point defects and grain boundaries. The cuprate (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x has high Tc = 92 K, κ ~ 95, and Gi ~ 10−2 and is a primary choice for high-current applications.15 It was grown epitaxially to a thickness of 900 nm using metal organic deposition, and its microstructure consists of point defects, a sparse distribution of Y2Cu2O5 (225) precipitates (diameter ~94 nm, spacing ~272 nm) and twin boundaries, all common in as-grown cuprate films.16,17

Results and discussion

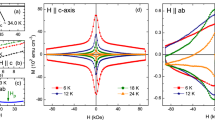

Using a SQUID magnetometer, we performed magnetization measurements M(t) ∝ J(t) to determine the temperature-dependent creep rate S(T), Jc, and Tc. We alternated between these measurements and thinning the films using a broad beam Ar+ ion mill to characterize changes in these parameters with decreasing sample thickness. Further details of the experimental procedures are provided in the Methods section. Figure 2a compares S(T) at different film thicknesses for Nb measured in a 0.3 T field. Creep is similar for d = 447 and 393 nm, while subsequent thinning causes successive increases in S(T) that are more pronounced at higher temperatures. This progression from a thickness-independent to thickness-dependent S(T) is suggestive of the sought-after 3D-to-2D transition.

Thickness-dependent vortex creep in Nb film. a Comparison of the temperature-dependent creep rates, S(T), for a Nb film at different thicknesses d in a field of 0.3 T. The error bars (standard deviation in the logarithmic fit to M(t)) are smaller than the point sizes. We were unable to measure creep below 5.5 K due to flux jumps. b Temperature dependence of the collective pinning length for vortex bundles in our Nb film based on Eq. (1), our experimental data for Jc (inset), and the assumption that λ(T = 0) ≈ 80 nm.36 c Difference in creep rate of thinned film and that of the original film (d = 447 nm) versus the ratio of the film thickness to the collective pinning length, d/Lc(T). Creep rate deviates from bulk behavior when film becomes thinner than \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{vb}}(T)\). The insets illustrate the bulk (right panel) and truncated (left panel) collective pinning volumes, applicable for d > Lc and d < Lc, respectively. d Creep versus film thickness at different temperatures on a log–log plot. The dotted lines are linear fits for \(d \le L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{vb}}\) used to extract the exponent α (slopes of fits) of the power-law S ∝ d−α, plotted in the inset

We now compare the experimental data with predictions from weak collective pinning theory,4,5 which distinguishes two main (bulk) regimes: the pinning volume may contain single vortices (sv) or vortex bundles (vb) with characteristic longitudinal and transverse correlation lengths

Here, Jd is the depairing current density, a0 = (4/3)1/4(Φ0/B)1/2 is the vortex spacing, B is the magnetic induction and γ > 1 is the uniaxial anisotropy parameter. Note that Eq. (1) neglects the narrow regime of small vortex bundles for which a0 < Lc < λ2/a0 and Rc rapidly grows from ξ to λ. The pinning energy governing the creep rate is Uc ≈ c66(ξ/Rc)2Vc, where c66 is the shear modulus. Given an applied field of 0.3 T (a0 ≈ 89 nm ~ λ) and Lc determined from critical current density data, the system clearly is in the vortex bundle regime, \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{vb}}\)(T) > λ2/a0, see Fig. 2b. Based on these findings, we re-plot the data from Fig. 2a to display the change in creep rate from that of the original film (ΔS) versus \(d{\mathrm{/}}L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{vb}}(T)\), see Fig. 2c. We observe that S abruptly deviates from bulk behavior when the film becomes thinner than Lc(T), revealing the 3D-to-2D transition.

Two-dimensional collective pinning was first experimentally realized in studies18,19,20,21,22 of the field-dependent pinning force in amorphous superconducting films of thickness \(d \ll L_{\mathrm{c}}\). On the 2D side of the transition, the longitudinal correlation length is capped by the sample thickness, Lc → d, and the transverse correlation length13,14

replace the bulk expressions in Eq. (1). The energy Uc then scales as

Plotting S(d) for fixed temperatures, Fig. 2d, we observe a relatively flat (d-independent) region at nearly all temperatures for large values of d and power-law behavior S ∝ d−α for small values of d. Using S ~ T/Uc, the exponent 0.5 < α < 1 (Fig. 2d inset) assumes values in agreement with Eq. (3).

The creep data further allows us to define the effective activation energy U* ≡ T/S = Uc + μT ln(t/t0), hence providing direct access to the glassy exponent μ. This exponent captures the diverging behavior of the current-dependent activation barrier U(J) ~ Uc(Jc/J)μ away from criticality, that is, for \(J \ll J_{\mathrm{c}}\), and assumes different values for creep of single vortices versus bundles.4 Near criticality, the behavior is non-glassy and the exponent is named p < 0 instead of μ. A detailed analysis of the system’s glassiness is provided in the Supplementary Information (see Fig. S5) and further confirms the transition from elastic to rigid vortex behavior at d ≈ Lc.

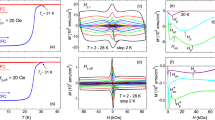

We performed a complementary study on the cuprate film at 1 T. The evolution of S(T) with thinning, plotted in Fig. 3a, again reveals successive increases in S that are more pronounced at higher temperatures. In the original film, S(T) is non-monotonic, showing a shallow dip between 25 and 45 K; this is typical of YBa2Cu3O7−x and has been associated with the presence of large precipitates.23 Notwithstanding a fixed density of precipitates at all thicknesses, the dip disappears with thinning, indicative of changes in vortex–precipitate interactions. Moreover, when the film is thinnest (d = 262 nm), the creep rate grows monotonically with T and qualitatively adheres to the Anderson–Kim model describing creep of rigid vortices.24

Thickness-dependent vortex creep in (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x film in a field of 1 T. a Comparison of the temperature-dependent creep rates, S(T), for the (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x (YGdBCO) film at different thicknesses d. The error bars (standard deviation in the logarithmic fit to M(t)) are smaller than the point sizes. b Collective pinning length \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{vb}}(T)\) for (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x in the bundle regime based on Eq. (1), our experimental data for Jc (inset), and the assumption that λab(0) ≈ 140 nm is equivalent to YBa2Cu3O7−x.37,38 The calculated pinning length is too small to account for the dependence S(d) observed in a

The calculated length \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{vb}}(T)\), shown in Fig. 3b, is far too small to reconcile the observed thickness dependence of S. We hence conclude that, though sparse, the large 225 precipitates of size \(b \gg L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{vb}}\) must substantially influence effective pinning scales.25,26,27 Accounting for these inclusions as strong defects, the pinning length cannot be smaller than b. This raises an important question: can a meaningful pinning length \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}(T)\) (mixed pinning, mp) be extracted from the experimental data in heterogeneously disordered samples?

Again, plotting S(d) on a log – log scale (Fig. 4a), we observe that at low temperatures S is relatively independent of d and conclude that creep is bulk-like, that is, Lc < d for all thicknesses. At higher temperatures, S and therefore the energy U* acquire a thickness dependence, which follows the power-law U* ∝ dα. The transition from the thickness-independent to thickness-dependent U* appears as a kink in U*(d), as shown in the inset to Fig. 4b. We identify \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\) as the position of this kink and find a linear dependence on temperature (Fig. 4b). This length decreases with decreasing magnetic field, as concluded from a similar analysis of data collected at 0.3 T, presented in detail in the Supplementary Information. This trend agrees with theoretical predictions within strong pinning theory.27

Pinning length in (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x film. a Creep rate versus film thickness at different temperatures for (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x (YGdBCO) film on a log – log plot. The dotted lines are linear fits for \(d \le L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}(T)\). b Effective pinning length \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\) at 0.3 and 1 T. (See Supplementary Information for all 0.3 T data). The circles and diamonds show points extracted from the U*(d) data. The inset shows an example of how \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\) was extracted for T = 10–25 K at 1 T. Linear fits to this data (solid lines) and extrapolations (dashed lines) defining \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}(T,H)\) are shown. c Difference in creep rate of thinned film and that of the original film (d = 900 nm) versus the ratio of the film thickness to the effective pinning length, \(d{\mathrm{/}}L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}(T)\). Creep rate increases sharply when film becomes thinner than \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\). The insets illustrate the bulk (right panel) and truncated (left panel) pinning volumes, applicable for \(d > L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\) and \(d < L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\), respectively

Figure 4c highlights the effectiveness of our method: there is an abrupt departure in S from that of the original film when the thickness falls below the extracted pinning length. We conclude that in the prevailing case of heterogeneously disordered superconductors, for which collective pinning by small defects and strong pinning by large precipitates coexist, a pinning length is indeed well defined. This length is much larger than predicted by collective pinning theory, consistent with theoretical expectations.25,26,27

The magnetic 3D-to-2D crossover should invoke a change in Jc versus d. Figure 5a shows the normalized Jc versus \(d{\mathrm{/}}L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\), using a criterion of Jc ≡ J(ti = 5s) (see Supplementary Information and references therein for details) and where \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\) is extracted from the creep measurements as discussed above. Around \(d{\mathrm{/}}L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\sim 1\), there is an abrupt transition from a thickness-independent to a thickness-dependent regime, at which point Jc increases with decreasing d. We observed similar behavior in a Nb film around d/Lc, for which results are displayed in Fig. 5b.

Increase in critical current with decreasing film thickness. a \(J_{\mathrm{c}}{\mathrm{/}}J_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{bulk}}\) at different temperatures versus the ratio of the film thickness to the effective pinning length, \(d{\mathrm{/}}L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}(T)\). Here, Jc is extracted using a criterion of ti = 5 s (see Supplementary Information for details) and \(J_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{bulk}}\) ≡ Jc(d = 871 nm) at each specified temperature. Jc increases sharply when film becomes thinner than \(L_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{mp}}\). b \(J_{\mathrm{c}}{\mathrm{/}}J_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{bulk}}\) for a Nb film cut from the same substrate as the film in which creep was measured. Here \(J_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{bulk}}\) ≡ Jc(d = 500 nm) and the data displayed represents film thicknesses d = 500, 270, 164, 138, 111, 85, and 58 nm

Governing the energy barrier to vortex motion, the pinning length plays a major role in the emergence of fascinating phenomena such as glassiness and plasticity. It is therefore a crucial parameter to consider when pursuing the ambitious materials-by-design paradigm and development of a universal description of vortex matter. This work opens the door for further studies to unveil pinning lengths in other superconductors and could impact work on other problems that similarly involve the interplay between disorder and collective interactions, such as systems containing skyrmions,28 domain walls,29 or disordered polymers.30

Methods

Film growth and characterization

The (Y0.77,Gd0.23)Ba2Cu3O7−x film measured in this study was grown epitaxially on buffered Hastelloy substrates using metal organic deposition from Y-trifluoroacetate, Gd-trifluoroacetate, and Ba-trifluoroacetate and Cu-naphthenate solutions. A stack of NiCrFeO, Gd2Zr2O7, Y2O3, MgO (deposited using ion beam-assisted deposition), LaMnO3, and CeO2 layers form the interposing buffer. Characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy, the film contains a sparse distribution (3 × 1019/m3) of Y2Cu2O5 precipitates, which are on average 94 nm in diameter and spaced 272 nm apart (see ref.17 for TEM images). The Nb film was deposited on a SiO2 substrate by DC sputtering and contains ~10-nm-sized grains.31 As discussed in the main text, Nb has low κ and low Gi, while (Y0.77,Gd0.23)Ba2Cu3O7−x has both high κ and Gi. The relevance of these parameters is as follows: κ is related to the energy required for vortex core formation (almost negligible in (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x) and Gi captures the relevance of thermal fluctuations in the material, that is, materials with larger Gi suffer more from vortex creep.4,9,32

Thinning was achieved by broad beam Ar+ ion milling on a rotating, water-cooled stage. To prevent significant changes in the surface roughness, we milled at a low beam voltage of 300 V and current of 12 mA. Atomic force microscopy studies revealed milling rates of ~12 and ~9 nm/min and root mean square surface roughnesses of 30 and 5 nm for the (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x film and Nb film, respectively. As a redundant verification of the rate calibration, the thickness of the (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x film after all milling steps was measured using focused ion beam and cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy.

Magnetization measurements

Magnetization studies were performed using a Quantum Design SQUID magnetometer. For all measurements, the magnetic field was applied perpendicular to the film plane. Creep data were taken using an established approach33 where the decay in the magnetization over time was captured by repeatedly measuring M every 15 s at a fixed T and H. To accomplish this, the field was initally swept high enough (ΔH > 4H*) that vortices, which first form at the film peripheries, permeate the center of the sample. In this case, H* is the field of full flux penetration and the Bean critical state model defines the vortex distribution. A brief measurement of M(t) in the lower branch was collected, then for the upper branch M was repeatedly measured for an hour. After subtracting the background (determined by the differences in the upper and lower branches) and adjusting the time to account for the difference between the initial application of the field and the first measurement (maximize correlation coefficient), \(S = - {\mathrm{d}}{\kern 1pt} {\mathrm{ln}}{\kern 1pt} M{\mathrm{/}}{\mathrm{d}}{\kern 1pt} {\mathrm{ln}} t\) was calculated from the slope of a linear fit to ln M versus ln t. The critical current density was calculated from the magnetization data using the Bean model,34,35 Jc = 20ΔM/[w(1 − w/3l)]. Here, ΔM is the difference between the first few points from the upper and lower branches of M(t), w ~ l ~ 4–5 mm specifies sample width and length. Tc was determined from temperature-dependent magnetization curves recorded at 0.002 T. For both the Nb film and the (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x film, thinning did not change Tc.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings in this study are available within the article or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Maiorov, B. Synergetic combination of different types of defect to optimize pinning landscape using BaZrO3-doped YBa2Cu3O7. Nat. Mater. 8, 398–404 (2009).

Kwok, W.-K. et al. Vortices in high-performance high-temperature superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 116501 (2016).

Miura, M. et al. Mixed pinning landscape in nanoparticle-introduced YGdBa2Cu3Oy films grown by metal organic deposition. Phys. Rev. B 83, 184519 (2011).

Blatter, G., Feigel’man, M. V., Geshkenbein, V. B., Larkin, A. I. & Vinokur, V. M. Vortices in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 1125–1388 (1994).

Larkin, A. I. & Ovchinnikov, Y. N. Pinning in type II superconductors. J. Low Temp. Phys. 34, 409–428 (1979).

Ovchinnikov, Y. N., & Ivlev, B. I. Pinning in layered inhomogeneous superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 43, 8024–8029 (1991).

Blatter, G., Geshkenbein, V. B., & Koopmann, J. A. G. Weak to strong pinning crossover. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 067009 (2004).

Malozemoff, A. P. & Fisher, M. P. A. Universality in the current decay and flux creep of Y-Ba-Cu-O high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 42, 6784–6786 (1990).

Eley, S., Miura, M., Maiorov, B. & Civale, L. Universal lower limit on vortex creep in superconductors. Nat. Mater. 16, 409–413 (2017).

Stan, G., Field, S. B. & Martinis, J. M. Critical field for complete vortex expulsion from narrow superconducting strips. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 097003 (2004).

Song, C., Defeo, M. P., Yu, K. & Plourde, B. L. T. Reducing microwave loss in superconducting resonators due to trapped vortices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 232501 (2009).

Wang, C. et al. Measurement and control of quasiparticle dynamics in a superconducting qubit. Nat. Commun. 5, 5836 (2014).

Brandt, E. H. Collective pinning in a film of finite thickness. J. Low Temp. Phys. 64, 375–393 (1986).

Kes, P. H., & Wördenweber, R. Computations on the dimensional crossover in collective pinning. J. Low Temp. Phys. 67, 1–15 (1987).

Wesche, R. High-temperature Superconductors: Materials, Properties, and Applications, Vol. 6 (Springer Science and Business Media, New York, 1998).

Foltyn, S. R. et al. Materials science challenges for high-temperature superconducting wire. Nat. Mater. 6, 631–642 (2007).

Miura, M. et al. Upward shift of the vortex solid phase in high-temperature-superconducting wires through high density nanoparticle addition. Sci. Rep. 6, 20436 (2016).

Kes, P. H. & Tsuei, C. C. Two-dimensional collective flux pinning, defects, and structural relaxation in amorphous superconducting films. Phys. Rev. B 28, 5126–5139 (1983).

Wordenweber, R., Kes, P. H. & Tsuei, C. C. Peak and history effects in two-dimensional collective flux pinning. Phys. Rev. B 33, 3172–3180 (1986).

Toyota, N., Inoue, A., Fukase, T. & Masumoto, T. Upper critical field and related properties of superconducting amorphous alloys Zr-Si. J. Low Temp. Phys. 55, 393–410 (1984).

Yoshizumi, S., Carter, W. L., Fukase, T. & Geballe, T. H. Flux-pinning and inhomogeneities or defects in amorphous superconducting Mo5Ge3 films. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 61 and 62, 589–594 (1984).

Osquiguil, E. J., Frank, V. L. P. & de la Cruz, F. Two dimensional collective flux pinning in melt spun superconducting amorphous Zr70Cu30. Solid State Commun. 55, 227–230 (1984).

Haberkorn, N. et al. High-temperature change of the creep rate in YBa2Cu3O7−δ films with different pinning landscapes. Phys. Rev. B 85, 174504 (2012).

Anderson, P. W. & Kim, Y. B. Hard superconductivity: theory of the motion of Abrikosov flux lines. Rev. Mod. Phys. 36, 39 (1964).

Gurevich, A. Pinning size effects in critical currents of superconducting films. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 20, S128–S135 (2007).

Koshelev, A. E. & Kolton, A. B. Theory and simulations on strong pinning of vortex lines by nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 84, 104528 (2011).

Willa, R., Koshelev, A. E., Sadovskyy, I. A., & Glatz, A. Strong pinning regimes by spherical inclusions in anisotropic type-II superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol 31, 1 (2018).

Reichhardt, C., Ray, D., & Reichhardt, C. J. O. Collective transport properties of driven skyrmions with random disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 217202 (2015).

Lemerle, S. et al. Domain wall creep in an ising ultrathin magnetic film. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 849–852 (1998).

Halpin-Healy, T., & Zhang, Y.-C. Kinetic roughening phenomena, stochastic growth, directed polymers and all that. Aspects of multidisciplinary statistical mechanics. Phys. Rep 254, 215–414 (1995).

Henry, M. D. et al. Stress dependent oxidation of sputtered niobium and effects on superconductivity. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 083903 (2014).

Ginzburg, V. L. Some remarks on phase transitions of second kind and the microscopic theory of ferroelectric materials. Sov. Phys. Solid State 2, 1824 (1961).

Yeshurun, Y., Malozemoff, A. P. & Shaulov, A. Magnetic relaxation in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 911–949 (1996).

Bean, C. P. Magnetization of high-field superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 36, 31–39 (1964).

Gyorgy, E. M., Van Dover, R. B., Jackson, K. A., Schneemeyer, L. F. & Waszczak, J. V. Anisotropic critical currents in Ba2YCu3O7 analyzed using an extended Bean model. Appl. Phys. Lett. 55, 283–285 (1989).

Grebinnik, V. G. et al. The comparative study of irreversibility effects in Nb Foil and High-temperature superconducting ceramics by μSR. Hyperfine Interact. 63, 123–130 (1990).

Farber, E., Deutscher, G., Contour, J. P., & Jerby, E. Penetration depth measurement in high quality YBa2Cu3O7-x thin films. Eur. Phys. J. 5, 159–162 (1998).

Langley, B. W., Anlage, S. M., Pease, R. F. W., & Beasley, M. R. Magnetic penetration depth measurements bya microstrip resonator technique of superconducting thin films. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 62, 1801 (1991).

Acknowledgements

All magnetization measurements (S.E.), ion milling and atomic force microscopy performed by S.E. at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies (CINT), contributions from L.C., and theory (R.W.) were funded by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Science and Engineering Division. CINT is a user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science. M.M. and M.S. are supported by JSPS KAKENHI (17H03239 and 17K18888) and a research grant from the Japan Power Academy. M.D.H. was supported by the LDRD program at Sandia National Laboratory (SNL). We acknowledge and thank the staff of the SNL MESA fabrication facility as well as Dr. Charles Thomas Harris of CINT at SNL for focused ion beam milling and cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy. R.W. also acknowledges support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) through the Early Postdoc.Mobility program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.E. conceived and designed the experiment, performed the magnetization measurements, ion milling, atomic force microscopy, data analysis, and assisted with theoretical analysis. R.W. spearheaded the theoretical analysis. S.E. and R.W. wrote the manuscript. L.C. assisted with theoretical analysis and manuscript preparation. M.L. assisted with data collection. M.M. and M.S. grew and performed the microstructure characterization on the (Y,Gd)Ba2Cu3O7−x films. M.D.H. deposited and performed the microstructure characterization on the Nb films.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eley, S., Willa, R., Miura, M. et al. Accelerated vortex dynamics across the magnetic 3D-to-2D crossover in disordered superconductors. npj Quant Mater 3, 37 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0108-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0108-1