Abstract

Area laws are a far-reaching consequence of the locality of physical interactions, and they are relevant in a range of systems, from black holes to quantum many-body systems. Typically, these laws concern the entanglement entropy or the quantum mutual information of a subsystem at a single time. However, when considering information propagating in spacetime, while carried by a physical system with local interactions, it is intuitive to expect area laws to hold for spacetime regions. In this work, we prove such a law for quantum lattice systems. We consider two agents interacting in disjoint spacetime regions with a spin-lattice system that evolves in time according to a local Hamiltonian. In their respective spacetime regions, the two agents apply quantum instruments to the spins. By considering a purification of the quantum instruments, and analyzing the quantum mutual information between the ancillas used to implement them, we obtain a spacetime area law bound on the amount of correlation between the agents’ measurement outcomes. Furthermore, this bound applies both to signaling correlations between the choice of operations on the side of one agent, and the measurement outcomes on the side of the other; as well as to the entanglement they can harvest from the spins by coupling detectors to them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

How much information is available to an observer, given access to a spacetime region, about the rest of spacetime? Because of the locality of physical interactions, the boundary of the region seems most relevant for information acquisition. Intuitively, we might expect this information to scale proportionally to the size of the region’s boundary.

We shall address this question within the framework of quantum lattice systems. The investigation of quantum information properties of such systems is of great interest in its own right, as they have profound implications both on the field of condensed matter physics and on quantum computing. Furthermore, such systems can serve as lattice approximations of relativistic quantum field theories. The vacuum state of such theories displays a rich entanglement structure1,2,3 which can be ‘harvested’, i.e. it is possible to produce an entangled state of two initially uncorrelated detectors by making them interact with the field alone.4,5,6,7,8,9 Fundamental bounds on such entanglement harvesting are also of great interest.

In quantum lattice systems with local interactions, the Lieb–Robinson bound provides a limit on the speed of propagation of information.10 As a result, an effective light-cone structure emerges. In ref. 11 it was shown that an observer, Bob, effectively cannot detect whether or not Alice has manipulated her part of the system in the past, if he performs measurements outside of her light cone. It was further shown that correlations between parts of the system cannot be created by the time evolution in time intervals shorter than that needed for a signal, traveling at the Lieb–Robinson velocity, to reach from one part to the other.

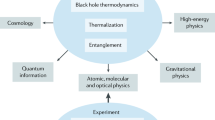

Area law bounds on the entanglement entropy are a further consequence of the locality of interactions. First studied in relation to black hole thermodynamics,12,13,14,15 they were observed to hold in ground states of non-critical quantum lattice systems (see ref. 16 for a review). They deal with the entanglement structure of specific states, e.g. ground states of local Hamiltonians, or their thermal states.17 Yet another property of local Hamiltonians11,18 is that the rate at which they generate entanglement between two regions of the lattice is governed by an area law.

The mentioned results provide bounds on the amount of information that can be shared between regions. In each bound the amount of information scales with the size of the region considered. It is worth noting that the scaling is not the same in all bounds. In the Lieb–Robinson bound there is a prefactor which scales with the volume of the smaller of the two regions,11 as opposed to the area law results. Scaling with time appears only in the results about entanglement rates.11,18 All these results demonstrate how the locality of interactions restricts the propagation of information between spacetime regions. The question of its overall spacetime scaling, however, remains open.

To address this question, we adopt an operational definition for the notion of propagation of information between spacetime regions. We consider two agents, Alice and Bob, restricted to probing a time-evolving lattice spin system in disjoint spacetime regions, using quantum instruments of their choice. We consider both signaling and non-signaling correlations between the settings and the outputs of the measurement devices used by Alice and Bob.

In this article, we prove a spacetime area law bound on correlations in the presence of local dynamics. We show that both the maximal correlation between measurement outcomes, and the maximal signaling capacity between spacetime regions, are bounded by the area of the boundary separating them. Note that this is a co-dimension 1 surface in spacetime whereas the above-mentioned results regarding entropy area laws for spacetime regions12,13,14,15 refer to the area of a co-dimension two surfaces in spacetime. We prove this bound for finite-dimensional quantum lattice systems in which time evolution is governed by local Hamiltonians, and for one-dimensional quantum cellular automata.

We shall employ purifications of the instruments used to probe the system. This will be shown to reduce the problem of bounding correlations to that of bounding the von Neumann entropy of the reduced state of ancillas used for the purification of Alice’s instruments. Apart from serving as a computational aid, the purified setup highlights the affinity of our setup to that of entanglement harvesting,4,5,6,7,8,9 where such ancillas are called probes or detectors.

The most general quantum instrument can be implemented by introducing an ancillary quantum system in a pure state (which we denote by |0〉); applying a unitary on both system and ancilla; and performing a projective measurement on a part of the composite system to obtain the recorded measurement outcome and the corresponding post-measurement state of the system.19 When performing a sequence of measurements, each one involving a fresh ancillary system, such projective measurements can be deferred to the end of the overall process. Up to that point, the physical system and the ancillas undergo a joint unitary evolution. In ref. 20 it was shown that the resulting state of the ancillas (before the projective measurements are made) can be represented by a matrix product state.21 This is illustrated in Fig. 1. Following the same approach, we will represent the state of the ancillas after the measurement process as a tensor network state.22

Equivalent representations of a purified quantum instrument. The recorded measurement outcome is produced by a projective measurement (represented by the dashed half circle) of the ancilla system (initially in the state |0〉). This measurement can be deferred to a later time. The LHS shows the details of the purification. The RHS representation is an isometry from the input space to the output and ancilla spaces. When consecutive measurements are performed on a system, the resulting state of the ancilla systems at the end of the process admits a matrix product state representation which is obtained by concatenating copies of the RHS.20

Results

For the sake of clarity we shall first present the setting of the problem for a system in one spatial dimension. In this case, the graphical representation of the problem is instructive and easy to follow (see Fig. 2). The generalization to higher spatial dimensions is straightforward and our results apply to spin lattices of any spatial dimension.

Consecutive local operations followed by Hamiltonian time evolution realize a tensor network state of the ancillas used to perform the operations. The circles on the left represent the initial state. The white squares represent local instruments with the upward pointing legs representing the ancillas, as in Fig. 1. The shaded rectangles represent the unitary time evolution operators. A is the spacetime region of interest. X is the number of spins on which measurements in A are performed—the spatial extent of A. T = τΔt is the total duration of A in time, where τ is the number of time steps and Δt is the duration of time evolution between measurements

Consider a ‘spin’ chain, i.e. identical d-dimensional quantum systems positioned on a one-dimensional lattice. Let \({\cal{H}}\) be the Hilbert space representing one such spin, we denote by \({\cal{L}}\left( {\cal{H}} \right)\) the space of linear operators on \({\cal{H}}\). Let the chain initially be in an arbitrary state \(\rho _0 \in {\cal{L}}\left( {{\cal{H}}^{ \otimes N}} \right)\) and evolve in time according to a unitary time evolution generated by a finite range interaction Hamiltonian \(H = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i h_i\), where the sum runs over all spins i in the chain, each term hi has a finite range, R, and acts on at most n(R) spins contained in a ball of radius R around spin i. We assume that the interaction strength is bounded by \(\left\| h \right\|: = \mathop {{{\mathrm {sup}}}}\nolimits_i \left\| {h_i} \right\|\) for any size of the lattice. For brevity we present the proof in the case of strictly finite range Hamiltonians. The same proof works for Hamiltonians with sufficiently strongly decaying interactions, precisely, for quasi-local Hamiltonians as per ref. 18

At times (t1,t2,…) a quantum instrument acts separately on each spin (for now, assume that this happens instantaneously, we shall relax this assumption in result 2). The different measurements (we use the terms measurement, quantum operation and quantum instrument interchangeably) are performed at spacetime points (x,t), where x is the position of the spin in the chain and t is the time of the measurement. We purify each measurement device, thereby associating to each spacetime point an ancillary quantum system. The state of the ancillas after interacting with the spins is given by the tensor network state shown in Fig. 2.

Let A be a spacetime region comprised of X neighboring spins and spanning a time interval of duration T = τΔt, where τ is the number of time steps and Δt is the length of time evolution between measurements (see Fig. 2). We measure the spatial extent of a system in units of the lattice spacing, so that in one dimension, length is equal to the number of spins. For ease of notation, the time intervals between measurements are taken to be equal. The same result holds for arbitrary time intervals. Alice controls the measurements inside the region A and Bob the ones outside of it.

We shall formulate our bound in terms of the quantum mutual information between the ancillas associated to the measurements performed by Alice and the rest of the system (which includes Bob’s ancillas and the physical spins at the end of the measurement process).

The quantum mutual information of a bipartite quantum system in a state \(\rho \in {\cal{L}}\left( {{\cal{H}}_{\mathrm {A}} \otimes {\cal{H}}_{\mathrm {B}}} \right)\) is given by19

where S(ρ) = −Trρ log ρ is the von Neumann entropy and ρA = TrBρ is the reduced state of the system A.

Before stating our results, we demonstrate that the quantum mutual information between the ancillas purifying the agents’ instruments is an upper bound on the operational quantities of interest, namely: (a) the classical mutual information between measurement outcomes of Alice and Bob; and (b) the classical channel capacity from Alice’s instrument settings to Bob’s outcomes when signaling is considered. Further note that the distillable entanglement is also bounded by the quantum mutual information.23

Quantum mutual information is non-increasing with respect to applying completely positive and trace preserving (CPTP) maps separately on each subsystem.19 In particular, tracing out parts of subsystems does not increase mutual information. We therefore assume w.l.o.g. that the initial state of the spins is pure. If it were a mixed state, we could consider a purification, and the mutual information would only be higher. For a pure system the quantum mutual information is equal to twice the von Neumann entropy of the reduced state.

The same monotonicity property further implies that the classical mutual information between the probability distributions for the outcomes of measurements performed by Alice and those performed by Bob, is bounded by the quantum mutual information (point (a)). To see this recall that those measurement outcomes are obtained by performing projective measurements on the ancilla systems and note that the map which transforms the state of the ancillas to a diagonal density matrix which encodes the probabilities for the measurement’s outcomes is CPTP.

When considering a signaling scenario in which Alice can choose an instrument setting a with probability p(a), we can encode this probability distribution in the state of an additional ancilla \(|p\rangle = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_a \sqrt {p(a)} |a\rangle _{}^{}\) and apply different unitaries conditioned on this state. As above, we can then bound the classical mutual information between p(a) and the probability distribution governing Bob’s outcomes. If our bound does not depend on the distribution p(a) (as will be the case in our results 1 and 2, since both do not depend on the initial state of the ancillas), then the classical channel capacity19 from Alice’s choice of settings to Bob’s outcomes is also bounded (point (b) above).

Note that in the case of one spatial dimension, if the evolution between time steps is given by a matrix product operator24 (this is exactly the case when the spins’ evolution is governed by a quantum cellular automaton,25 since those have been shown to coincide with translationally invariant matrix product unitary operators26), then the proof of a spacetime area law bound on the quantum mutual information follows immediately from the representation of the state of the ancillas as a two-dimensional tensor network state in Fig. 2. To see this note that tensor network states obey an area law bound on the entanglement entropy of subsystems.22 Replacing the time evolution operators in Fig. 2 by matrix product operators we see that the number of bonds cut by the red line defining Alice’s subsystem equals the area of the spacetime region A (=2T + 2X). Thus, we obtain an upper bound on the entropy of Alice’s reduced density matrix which is proportional to \(|\partial {\mathbf{A}}|_{}^{}\).

We shall now state our results for spin lattices of any spatial dimensions.

Result 1 Let a spin lattice in D dimensions, with each spin described by a d-dimensional Hilbert space, initially be in a state ρ0, and let the spins evolve in time according to a finite range Hamiltonian \(H = {\sum} h_i\) with range R and bounded interaction strength \(\left\| h \right\| = \mathop {{{\mathrm {sup}}}}\nolimits_i \left\| {h_i} \right\|\) independently of system size. Let arbitrary quantum instruments be applied individually on each spin at times (t1,t2,…). Let Σ be a subset of the lattice and let (tα,tβ) be a time interval so that together they define a spacetime region A = Σ×(tα,tβ). Let ρ be the state of the combined system of spins and ancillas at the end of the measurement process; then there exists a constant C > 0 which depends only on D and R, such that the following bound holds for the quantum mutual information between the ancillas (denoted A) corresponding to measurements performed inside the region A and the rest of the system Ā:

where |∂A| = 2|Σ| + T|∂Σ|, with T = tβ−tα ( = τΔt for equal time steps) and where ∂Σ denotes the boundary of the region Σ and |⋅| counts the number of elements in a set.

The proof of Result 1 is given in the “Methods” section below. From the proof it will become clear that the same bound holds even when both Alice and Bob are allowed to perform collective measurements within their regions at each time step, as well as, when they are allowed to reuse ancillas from previous time steps for their measurements. This observation leads to the following extension of Result 1 to a setting where measurements are continuous in time, particular cases of which are entanglement harvesting scenarios.

Result 2 Let a and b be arbitrary finite dimensional ancillary systems; let Σ be a subset of the spin lattice and \({\bar \Sigma }\) be its complement; and let H0 be a finite range Hamiltonian for the spins with range R as in Result 1. Let the system initially be in a pure state \(|\psi \rangle _{\Sigma \bar \Sigma } \otimes |0\rangle _a \otimes |0\rangle _b\). Let \({\cal{T}} = (t_\alpha ,t_\beta )\) be a time interval of length T = tβ−tα and let the time-dependent Hamiltonian of the system be

where HX,Y denotes a time-dependent interaction Hamiltonian between systems X and Y; and \({\cal{X}}_{\cal{T}}(t)\) the indicator function of the interval \({\cal{T}}\) (equals unity for \(t \in {\cal{T}}\) and zero otherwise). For any t ≥ tβ, the quantum mutual information between the ancillas a and b satisfies:

were the constant C depends only on D and R as in Result 1;

The proof of Result 2 is given in the “Methods” section below.

Discussion

We have considered local operations performed on a lattice spin system evolving under local dynamics. We showed that the mutual information between outcomes of local measurements is bounded by a spacetime area law. In particular, the amount of classical information that an agent, localized within a spacetime region, can send outside or infer about the outside is at most proportional to the area of the region’s boundary. Agents trying to harvest entanglement from the spin lattice by coupling detectors to it will run into the same bound.

The results obtained in the present article complement the results in ref. 11 There, the Lieb–Robinson bound is used to determine where information can travel in (discretized) spacetime. Our result bounds how much of it can be shared between spacetime regions. Furthermore, this work is a rigorous demonstration of an intuitively compelling idea that provides a link between quantum information and spacetime geometry. This idea, that information travels across boundaries of spacetime regions, is at the heart of a recent approach to the foundations of quantum theory,27,28 where it is used to motivate the association of quantum states to boundaries of arbitrary spacetime regions.

The proven bounds hold independently of the instruments used, the details of the purification and of the dimensions of the ancillary systems, and can be, therefore, regarded as an intrinsic property of the dynamics. Based on this observation, we suggest that the maximal mutual information between ancillary systems of measurement devices can be used as a measure of correlation intrinsic to a general quantum process. We discuss this further in a supplement to this article, a link to which can be found in the “Additional Information” section. There we define the proposed measure precisely within the process matrix formalism.29 This discussion is intended mainly for readers interested in various operational approaches to multipartite signaling quantum correlations.29,30,31,32,33,34

We have restricted our analysis to finite-dimensional systems in a non-relativistic setting. In relativistic quantum field theory, the dimension of the local Hilbert space at one spacetime point is infinite, which makes the results presented here unapplicable a priori. However, it seems reasonable to expect that a similar result should hold for relativistic quantum field theories which can be accurately simulated by a spin lattice with local interactions (see e.g. refs. 35,36,37). We expect that by restricting the admissible initial states and Hamiltonians, similar bounds could be obtained for regularized quantum field theories. We leave these questions for future study.

Methods

We first prove Result 1. As in the “Results” section, we begin by considering the one-dimensional case. Consider the following division of the spins and ancillas into three sets: (A) the ancillas inside the region A (encircled by the dashed red line in Fig. 2); (B) the spins which Alice measures; and (C) the rest of the spins and ancillas. The sequence of measurements can now be represented by the circuit diagram in Fig. 3, which is key to understanding how the subsystem A gets entangled with the rest of the system.

The circuit representation of Fig. 2. As described in the main text, subsystem A consists of the ancillas inside the region A (encircled by the dashed red line in Fig. 2); subsystem B consists of the spins which Alice measures; subsystem C consists of the rest of the spins and ancillas. The white gates correspond to the action of the instruments (unitary interaction between spins and ancillas). The shaded gates represent the unitary time evolution. The time axis is aligned with that of Fig. 2

Denote by t0 the time of the last measurement which precedes the measurements inside A, let tm: = t0 + mΔt and let tf be the time of the final measurement. From tτ onward, the system A does not interact with the system BC (see Fig. 3), therefore the entropy of A at the end of the entire process, SA(tf), which is the quantity which we wish to bound, is equal to SA(tτ).

In the time interval (t0,tτ) systems AB and C interact only via the time evolution operators acting on the physical spins. The small incremental entangling (SIE) theorem proved in refs. 18,38 bounds the rate of entanglement generation by the time evolution operator and allows us to bound the increase of SC = SAB with each time step. Using a Trotter expansion of the time evolution operator, it is easily shown that the only terms in the Hamiltonian able to generate entanglement (increase SC) are the ones that act across the boundary between systems B and C. When there are M such terms, i.e. when the Hamiltonian decomposes as \(H = H_C + H_B + \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{i = 1}^M H_{CB}^i\), and when each term is supported on at most n spins, the SIE theorem implies that the change of the entropy SC after evolving for a (finite) period of time Δt is bounded by

where c is a numerical constant from the SIE theorem.

In the 1D case, M— the number of interaction terms between systems B and C, is equal to 2(n−1). Next, bound the total increase in SC in the time interval of interest by

where in the last step we used the fact that at time t0 the system AB is in a product state and the state of A is pure. Using the triangle inequality for SAB39 and Equation 1 we obtain

Recalling that SA(tτ) = SA(tf) we obtain

where dB is the dimension of \({\cal{H}}_B\), i.e. dB = dX, and we bounded SB(t) by its maximum possible value. Plugging in the bound for ΔS we obtain the desired area law

where C(n): = 2c(n−1)2 and c from the SIE theorem (w.l.o.g. \(\left\| h \right\|c > 1\)). This proves Result 1 in the case of one spatial dimension (since \(|\partial {\mathbf{A}}| = 2X + 2T_{}^{}\)).

The proof is essentially the same when space is D-dimensional. The circuit diagram representation in Fig. 3 holds true. It remains only to compute M, the number of interaction terms across the boundary between systems B and C. Let n(D,R) be the number of spins inside a ball of radius R. For a finite range Hamiltonian with range R, the number of interaction terms acting on a single spin in the lattice is then at most n(D,R). Ignoring multiple counting of the same terms, we can bound M by \(|\partial \Sigma | \cdot n(D,R)_{}^{}\). Plugging this into the above ΔS and using \(S_B \le |\Sigma |{\mathrm {log}}\,d_{}^{}\) in eq (1) proves Result 1.

For the proof of Result 2 first note that Fig. 3 does not change neither if both Alice and Bob are allowed to perform collective measurements at each time step, nor if they reuse ancillas from previous time steps. Further note that only the time interval \({\cal{T}}\) is of interest because before and after it the ancilla a does not interact with any other system. Next we use the Trotter decomposition in order to arrive to a setting with discrete time steps, in which we can apply the same reasoning as in the proof of Result 1. Split the time interval \({\cal{T}}\) into m equal intervals, and in each one approximate the time evolution operator using the (first order) Lie–Trotter–Suzuki product formula.40 The approximate time evolution operator takes the form:

where tl is the middle of the lth time interval \(t_l = t_\alpha + \frac{{l \times T}}{m} - \frac{T}{{2m}}_{}^{}\). When applied to the initial state of the system, this sequence of unitary operators is described by the same circuit diagram Fig. 3 with subsystems: A: = a, B: = Σ and \(C: = \bar \Sigma \cup b_{}^{}\). I.e. the operators \({\mathrm {e}}^{ - i\frac{T}{{2m}}H_0}\) are represented in Fig. 3 by the gray gates; and \({\mathrm {e}}^{ - i\frac{T}{{2m}}H_{b,\bar \Sigma }}\) and \({\mathrm {e}}^{ - i\frac{T}{{2m}}H_{a,\Sigma }}\) by the white gates. For any m, Fig. 3 and the entropy inequalities in the proof of Result 1, imply that the von Neumann entropy of the ancilla a is bounded by the spacetime area law corresponding to the box \(\Sigma \times {\cal{T}}\) (there are τ = 2m time steps of duration \(\frac{T}{{2m}}\)). This bound holds true for any m and does not depend on its value. In ref. 40 it was shown that for a sufficiently smooth time-dependent Hamiltonian, the error of the Lie–Trotter–Suzuki formula vanishes as m tends to infinity. Using the continuity of the von Neumann entropy with respect to the state, we conclude that the same bound holds for the exact time evolution. The bound on the quantum mutual information follows from the fact that for pure states it is equal to twice the von Neumann entropy of the reduced state, and the fact that it is non-increasing with respect to tracing out subsystems.19

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Unruh, W. G. Notes on black-hole evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 14, 870–892 (1976).

Summers, S. J. & Werner, R. The vacuum violates bell’s inequalities. Phys. Lett. A 110, 257–259 (1985).

Summers, S. J. & Werner, R. Bell’s inequalities and quantum field theory. ii. Bell’s inequalities are maximally violated in the vacuum. J. Math. Phys. 28, 2448–2456 (1987).

Martin-Martinez, E., Brown, E. G., Donnelly, W. & Kempf, A. Sustainable entanglement production from a quantum field. Phys. Rev. A 88, 052310 (2013).

Reznik, B., Retzker, A. & Silman, J. Violating bell’s inequalities in vacuum. Phys. Rev. A 71, 042104 (2005).

Reznik, B. Entanglement from the vacuum. Found. Phys. 33, 167–176 (2003).

Olson, S. J. & Ralph, T. C. Entanglement between the future and the past in the quantum vacuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 110404 (2011).

Sabín, C., Peropadre, B., del Rey, M. & Martin-Martinez, E. Extracting past–future vacuum correlations using circuit qed. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 033602 (2012).

Retzker, A., Cirac, J. I. & Reznik, B. Detecting vacuum entanglement in a linear ion trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 050504 (2005).

Lieb, E. H. & Robinson, D. W. The finite group velocity of quantum spin systems. Commun. Math. Phys. 28, 251–257 (1972).

Bravyi, S., Hastings, M. B. & Verstraete, F. Lieb-robinson bounds and the generation of correlations and topological quantum order. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 050401 (2006).

Srednicki, M. Entropy and area. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 666–669 (1993).

Callan, C. & Wilczek, F. On geometric entropy. Phys. Lett. B 333, 55–61 (1994).

Bombelli, L., Koul, R. K., Lee, J. & Sorkin, R. D. Quantum source of entropy for black holes. Phys. Rev. D 34, 373–383 (1986).

Sorkin, R. D. 1983 paper on entanglement entropy: “On the Entropy of the Vacuum outside a Horizon”. (B. Bertotti, F. de Felice & A. Pascolini, eds) In Proc. 10th International Conference on General Relativity and Gravitation, Padua, Italy, July 4–9, 1983, Contributed Papers, vol. II, pp. 734–736, (Consiglio Nazionale Delle Ricerche, Roma, 1983).

Eisert, J., Cramer, M. & Plenio, M. B. Colloquium: area laws for the entanglement entropy. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 277–306 (2010).

Wolf, M. M., Verstraete, F., Hastings, M. B. & Cirac, J. I. Area laws in quantum systems: mutual information and correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 070502 (2008).

Mariën, M., Audenaert, K. M. R., Van Acoleyen, K. & Verstraete, F. Entanglement rates and the stability of the area law for the entanglement entropy. Commun. Math. Phys. 346, 35–73 (2016).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010).

Markiewicz, M., Przysiężna, A., Brierley, S. & Paterek, T. Genuinely multipoint temporal quantum correlations and universal measurement-based quantum computing. Phys. Rev. A 89, 062319 (2014).

Pérez-García, D., Verstraete, F., Wolf, M. M. & Cirac, J. I. Matrix product state representations. Quantum Inf. Comput. 7, 401 (2007).

Verstraete, F., Murg, V. & Cirac, J. Matrix product states, projected entangled pair states, and variational renormalization group methods for quantum spin systems. Adv. Phys. 57, 143–224 (2008).

Devetak, I. & Winter, A. Distillation of secret key and entanglement from quantum states. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 461, 207–235 (2005).

Cirac, J. I., Pérez-García, D., Schuch, N. & Verstraete, F. Matrix product density operators: Renormalization fixed points and boundary theories. Ann. Phys. 378, 100–149 (2017).

Schumacher, B. & Werner, R. F. Reversible quantum cellular automata, arXiv:quant-ph/0405174 (2004).

Cirac, J. I., Pérez-García, D., Schuch, N. & Verstraete, F. Matrix product unitaries: structure, symmetries, and topological invariants. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2017, 083105 (2017).

Oeckl, R. A local and operational framework for the foundations of physics, arXiv:1610.09052[quant-ph] (2016).

Oeckl, R. A. “General boundary” formulation for quantum mechanics and quantum gravity. Phys. Lett. B 575, 318–324 (2003).

Oreshkov, O., Costa, F. & Brukner, Č. Quantum correlations with no causal order. Nat. Commun. 3, 1092 (2012).

Chiribella, G., D’Ariano, G. M. & Perinotti, P. Quantum circuit architecture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 060401 (2008).

Chiribella, G., D’Ariano, G. M. & Perinotti, P. Theoretical framework for quantum networks. Phys. Rev. A 80, 022339 (2009).

Hardy, L. The operator tensor formulation of quantum theory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 370, 3385–3417 (2012).

Cotler, J., Jian, C.-M., Qi, X.-L. & Wilczek, F. Superdensity operators for spacetime quantum mechanics. J. High. Energy Phys. 2018, 93 (2018).

Pollock, F. A., Rodríguez-Rosario, C., Frauenheim, T., Paternostro, M. & Modi, K. Non-markovian quantum processes: complete framework and efficient characterization. Phys. Rev. A 97, 012127 (2018).

Jordan, S. P., Lee, K. S. M. & Preskill, J. Quantum algorithms for quantum field theories. Science 336, 1130–1133 (2012).

Martinez, E. A. et al. Real-time dynamics of lattice gauge theories with a few-qubit quantum computer. Nature 534, 516 EP- (2016).

Preskill, J. Simulating quantum field theory with a quantum computer. In Proc. 36th International Symposium on Lattice Field Theory (Lattice 2018), (East Lansing, MI, USA, 2018). https://doi.org/10.22323/1.334.0024.

Van Acoleyen, K., Mariën, M. & Verstraete, F. Entanglement rates and area laws. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 170501 (2013).

Araki, H. & Lieb, E. H. Entropy inequalities. Comm. Math. Phys. 18, 160–170 (1970).

Wiebe, N., Berry, D., Hoyer, P. & Sanders, B. C. Higher order decompositions of ordered operator exponentials. J. Phys. A 43, 065203 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank Frank Verstraete for bringing the SIE theorem to our attention and Marius Krumm, Alessio Belenchia, Simon Milz and Jordan Cotler for fruitful discussions. We acknowledge the support of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) through the Doctoral Program CoQuS and the project I-2526-N27 and the research platform TURIS, as well as support from the European Commission via Testing the Large-Scale Limit of Quantum Mechanics (TEQ) (No. 766900) project. P.A.G. acknowledges support from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Nature et Technologies (FRQNT). This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.B. contributed to the initial idea for this work. I.K. developed the idea and formulated the problem as it is presented. I.K. and P.A.G. proved the results under the supervision of C.B. All authors contributed to the final version of both article and supplementary discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kull, I., Allard Guérin, P. & Brukner, Č. A spacetime area law bound on quantum correlations. npj Quantum Inf 5, 48 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0171-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0171-x