Abstract

Respiratory diseases remain a significant cause of global morbidity and mortality and primary care plays a central role in their prevention, diagnosis and management. An e-Delphi process was employed to identify and prioritise the current respiratory research needs of primary care health professionals worldwide. One hundred and twelve community-based physicians, nurses and other healthcare professionals from 27 high-, middle- and low-income countries suggested 608 initial research questions, reduced after evidence review by 27 academic experts to 176 questions covering diagnosis, management, monitoring, self-management and prognosis of asthma, COPD and other respiratory conditions (including infections, lung cancer, tobacco control, sleep apnoea). Forty-nine questions reached 80% consensus for importance. Cross-cutting themes identified were: a need for more effective training of primary care clinicians; evidence and guidelines specifically relevant to primary care, adaption for local and low-resource settings; empowerment of patients to improve self-management; and the role of the multidisciplinary healthcare team.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) impose a significant burden on global health1. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019 suggested that respiratory conditions account for 7.7 million deaths per year1; CRD and respiratory infections (including tuberculosis) account for the third and fourth causes of death after cardiovascular disease and cancer2,3. Furthermore, the number of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) for CRD has increased by 20% since 19902,3. Tobacco smoking, the leading cause of CRD, is the second most important risk factor for global disease burden while indoor and outdoor air pollution are included in the top ten risk factors2. Commentaries by the GBD highlight the gap between current policies, activity and burden and the importance of universal health coverage3.

Primary care has a core role in the prevention, diagnosis and management of all respiratory diseases4; indeed, respiratory symptoms are the most common reason for primary care consultations5. However, significant evidence gaps remain, with a corresponding lack of evidence-based guidelines, quality standards and training to support primary care practice5,6. Progress is further challenged by the diversity of healthcare issues presented in primary care and the various models adopted for primary care worldwide5. Prioritising research needs helps guide researchers, research funders, and policymakers and will ultimately improve clinical guidelines and patient care globally7. Although relevant prioritisation studies exist8,9, there is still a need for a systematic and transparent approach in the specific area of primary care respiratory research7, and furthermore to ensure that the priorities are relevant to countries with different risk factor profiles and phases of development10. To date, there has been a general lack of investment in primary care respiratory research and an up-to-date specific needs statement will provide impetus to redress that balance11.

The International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) is a clinically-led charity that aims to promote research into the care, management and prevention of respiratory diseases in the community12. Its vision is a “world breathing and feeling well through universal access to right care”. Current membership includes 37 full and 24 associate member countries12 representing an estimated 155,000 primary healthcare professionals worldwide from high-, middle- and low-income countries in Europe, Asia, North and South America, Australia, and Africa13. In 2010, the IPCRG published its first Research Needs Statement for primary care respiratory research, identifying 145 research questions within five domains: asthma, rhinitis, COPD, smoking and respiratory infections6. This was prioritised in 2012 through an e-Delphi exercise culminating in a final list of 62 questions14. Now, 8 years on, changing needs and contexts require an update.

In this paper, we provide a new agenda for primary care respiratory research, obtaining consensus on the most important respiratory research questions from the perspective of practising primary care healthcare professionals representing a wide range of backgrounds and settings worldwide.

Methods

Overview of the e-Delphi processes

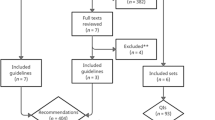

An e-Delphi exercise with three rounds was undertaken to build consensus on the most important priorities for respiratory research in primary care15,16 (Fig. 1). It commenced in May 2019 and was completed in August 2020 and included research questions suggested by practising primary healthcare professionals from across the world, with input from a panel of experts to verify and refine these questions, and two further rounds to rate the priorities. In addition, the open comments from the first Delphi round were analysed qualitatively to identify cross-cutting themes.

Recruitment

National coordinators from all IPCRG member countries were asked to purposively select and invite (by email) clinicians (doctors, nurses and any other healthcare professionals) working with respiratory patients in community settings in their countries to represent a broad range of views and experience. Specific inclusion criteria included the ability to complete online surveys in English and working in/with primary care settings to deliver care to patients with respiratory conditions.

e-Delphi 1: initial open-ended questionnaire

All data were collected through the Jisc Online Survey tool17 The initial questionnaire included three open questions seeking opinions on the most common respiratory conditions encountered in their clinical practice; the most clinically important conditions (in terms of burden and impact) and to suggest research questions relevant to their stated conditions for which they perceived evidence to be lacking. Participants were asked to consider the following domains: diagnosis, management, monitoring, self-management and prognosis. This questionnaire was piloted for clarity and ease of use by members of the IPCRG Research Committee and amended accordingly.

Evidence verification stage

To ensure that the questions suggested by participants reflected genuine evidence gaps and were answerable as research questions, 27 academic experts (Supplementary Table 1) with topic-specific expertise related to primary care, associated with the IPCRG, reviewed and verified evidence against the questions suggested by participants, refining and grouping similar questions, removing duplicates and adding questions where appropriate (including referring to unanswered questions from the previous prioritisation exercise5,14) to produce a final list of relevant and answerable questions. Experts were provided with instructions and a standardised proforma to produce the modified final questions. Additionally, they were asked to provide justification and evidence from the literature in support of their final list of questions.

e-Delphi round 2: first rating stage

All participants from the e-Delphi round 1 were invited to rate each question from the final list of research questions through two e-Delphi rating stages. During the first rating stage, participants rated each question on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 to 5 based on clinical importance (1 = Not at all important to 5 = Very important).

e-Delphi round 3: second rating stage

All participants from the e-Delphi round 2 were invited to re-rate the same list of questions from the previous round. At this stage, each participant was asked to consider the mean score, their individual score and any justification/comments provided by the participants on the questions in e-Delphi round 2, before re-rating the questions. Consensus for the e-Delphi was defined in round 3 for any question when 80% or more of participants rated it as 4 or 5 (important or very important).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present the characteristics of participants and responses. Treemap charts were used to present the relative proportions of conditions mentioned in the questions. All questions were ranked by consensus score within three main topics: Asthma, COPD and Other, and within each topic, further ranked within 5 domains: prevention, diagnosis, management, self-management, monitoring and prognosis. The mean rating score was used in the final ranking to separate questions with the same consensus score. In the few cases where the consensus score and the mean rank score were identical, questions were listed in alphabetical order. All analyses were carried out using the analysis functions in the Jisc Online Survey tool and Microsoft Excel.

In-depth qualitative analysis of cross-cutting themes from the initial questionnaire

The qualitative analysis focussed on the raw open-ended research questions received in the initial questionnaire and aimed to highlight cross-cutting needs, issues and possible solutions relevant to the care of respiratory patients in primary care. Thematic analysis was carried out by AAA using NVIVO 12 software. Three other authors (RJ, PA, KL) independently reviewed the data, which was followed by a discussion between these four authors to reach an agreement on the final themes.

Ethics

This study was approved by the University of Birmingham Ethics Committee (ERN_19-0303B). The study complied with all relevant ethical regulations for work with human participants, and informed consent was obtained from all participants at the start of the online survey.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Participants

A total of 112 participants from 27 countries took part in the initial online e-Delphi survey. Participants came from a wide range of backgrounds, roles, and experiences (see Table 1). Participants represented all main global regions including Europe (n = 46, 41%), Asia (n = 37, 33%), Africa (n = 14, 12.5%), South America (n = 9, 8%), North America (n = 3, 2.7%) and Oceania (n = 3, 2.7%). There were similar numbers of high-income and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) represented, but with a higher proportion of participants from LMICs (n = 67, 60%). Supplementary Table 2 provides further detail on the distribution of participants within the high-, middle- and low-income countries.

Women accounted for 58% (n = 65) of the participants, and most (n = 90, 80.3%) were between the ages of 25–54 years. While some participants worked in hospital settings (also treating community patients) (n = 16, 14.3%), the majority worked mainly in primary care or community settings (n = 74, 66.1%). Overall, 65 (58%) were family physicians, 13 (11.6%) hospital doctors, 12 (10.7%), clinician-researchers, 11 (9.9%) were nurses and 8 (7.1%) were other healthcare workers. Sixty-six (58.9%) participants reported being in their roles for more than ten years, and 72 (64.3%) had respiratory-related special interests or qualifications. Rounds 2 and 3 included 52 and 34 of the original respondents respectively with a generally similar demographic distribution to round 1 except in round 3 where a larger proportion of women remained than in previous rounds (n = 22, (65%) women), a lower proportion of family physicians (n = 14, (41%)), but a greater proportion with more experience (n = 25 (73%)) reported 10 or more years’ experience in their role). The income distribution of countries was generally similar throughout the 3 rounds.

Responses to the initial survey (round 1)

Question 1 (most common conditions)

Asthma was the most frequently mentioned respiratory condition encountered by respondents in their clinical practice (17.2%), followed by COPD (15.2%). However, as a clustered group of conditions, respiratory infections (TB, pneumonia, URTI, bronchitis/bronchiolitis, influenza) were mentioned most often (34.8% of all responses). Respiratory symptoms such as cough and breathlessness rather than specific clinical conditions were mentioned in 6.7% of responses.

Question 2 (most important conditions)

Although respiratory infections as a clustered group of conditions were perceived to be the most clinically important (29.9%), asthma was reported to be the most important single condition (25.7%), followed by COPD (24.5%), Fig. 2 illustrates the proportional distribution (percentages) of the most clinically important respiratory conditions.

Suggested research questions (question 3) and the Evidence Verification Stage

A total of 608 research questions were suggested by participants and grouped into 19 topics representing common categories of respiratory conditions. After verification and review by the expert group, and removal of duplicates, 176 research questions were finalised, categorised pragmatically into 14 topics and entered into the remaining two e-Delphi rounds. Figure 3 illustrates the proportional distribution (frequencies) of respiratory research questions as finalised by experts in the Evidence Verification Stage. The greatest proportion of questions was related to the management of COPD, followed by asthma self-management, asthma management, COPD diagnosis and screening, tuberculosis in primary care and tobacco control.

Consensus and ranking

Overall, 80% consensus was reached in 49 (27.7%) of the 176 rated questions. Asthma accounted for 19 (38.8%) of these questions while COPD accounted for 17 (34.7%) questions. Two questions (4%) reached a consensus of 100%: “What is the best way to manage chronic/ persistent cough in primary care?” and “What are the best ways to monitor asthma in primary care?”. Furthermore, 20 (40%) questions reached 90–99% consensus, while 27 questions (55.1%) reached a consensus of 80–89%. Table 2 lists the top 10 questions by consensus scores. Detailed rankings within asthma, COPD and other respiratory conditions are provided in Tables 3 to 5. Supplementary Table 3 lists all 176 questions with their scores.

Qualitative analysis of cross-cutting themes from the initial questionnaire

A thematic analysis of the original 608 questions contributed by participants produced six cross-cutting themes relevant to primary care clinicians (Table 6) (Fig. 4). Despite the availability of relevant evidence, the first main theme highlights a need for education and accessible guidelines tailored for the primary care context reflecting a lack of awareness by some primary care clinicians of current recommendations about how to manage respiratory conditions. The second main theme provides insight into gaps in evidence for diagnosing and treating respiratory conditions in primary care. Themes 3 and 4 focus on the need for locally relevant information, both in terms of local evidence to inform decisions but also locally relevant and practical solutions for primary care, and particularly in low-resource settings. The final two areas of interest were the need to improve patient empowerment to manage their own conditions and the growing importance of the wider multidisciplinary healthcare team.

Discussion

We have used the e-Delphi method to rank the global priorities for respiratory research in primary care by drawing on the views and experiences of primary healthcare professionals from a wide range of settings and backgrounds. This supersedes the previous 2012 IPCRG priorities14 and uniquely provides a primary care perspective on respiratory problems.

While respiratory infections as a clustered group of conditions remained the most frequent and clinically important reason for consultation in primary care, COPD and asthma were considered the most frequent and clinically important individual conditions. This reflects both our previous findings14 and the current global burden18. TB was highlighted more frequently than in the 2012 IPCRG priority exercise, reflecting greater involvement of clinicians from LMICs.

While the most common research questions suggested by participants related to the diagnosis, management and self-management of COPD and asthma, there were a significant number of questions relating to tobacco control, reflecting a worldwide lack of progress in this area, especially in LMIC countries10,19. However, after the consensus-building stages of the e-Delphi, the most highly ranked research priorities (Table 2) concerned the management of chronic cough, brief advice for smoking cessation, management of multimorbidity, adherence to inhalers, monitoring of asthma and earlier diagnosis of COPD. The findings reflect the wide range of problems encountered in primary care, from prevention through to management of complexity, and emphasise the need for influencing behaviour change among both patients and clinicians. Many questions also related to how best to implement known effective interventions.

Additional cross-cutting themes included questions involving the role of the multidisciplinary team, the need for locally relevant data and guidance, empowerment of patients to be involved in their own healthcare, and the use of simple accessible tests for diagnosis and monitoring. A further theme identified the need for more effective clinical education for delivering best-practice care.

Compared with our previous prioritisation exercise14, there were a greater number of participants, fewer with an academic focus, and more from LMIC settings. In addition, open-ended questions were sought from a wider range of healthcare professionals without restriction on broad topic areas. This approach was reflected in our findings, with a more diverse range of research questions and the inclusion of additional topics e.g. TB, sleep apnoea and lung cancer. New topics emerged as priorities, such as the need for research about shared and multidisciplinary care, and the need for greater understanding of the role of inhaled corticosteroids in the management of COPD and asthma. However, some research topics remained important including the need for simple and accessible tools and tests, improvement of patient self-management skills (including inhaler adherence), and the most efficient and effective ways to help people quit tobacco in busy primary care settings. Research questions about comorbidities have progressed from simple descriptions to the management of people with multimorbidity. Training and education of primary care professionals remains an important topic.

Since the last IPCRG research prioritisation exercise, there have also been a number of other relevant respiratory research prioritisation exercises20,21,22,23 although all are more narrow in scope, focussing on specific conditions or geographical settings. The exercise specific to Portugal was based on the previous IPCRG research needs and set in primary care20. Similar to our recent findings, they emphasised the importance of methods of empowering patient self-management, optimising adherence to asthma and COPD medication and inhaler technique and reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing20. The patient-led EARIP asthma programme also prioritised optimising self-management support and medication adherence/inhaler technique but also highlighted the need for simple diagnostic tools and relevant training for healthcare professionals21. Another project-focused prioritisation publication considered specifically the research needs in LMIC countries in South Asia, prioritising research questions relevant to COPD awareness and early identification22. The James Lind alliance projects are more specific, and the current COPD exacerbation project is yet to be report24.

A major strength of this study is the large sample size and diverse representation of the participants from high-, middle- and low-income countries. While most participants in this study were primary care physicians, there was a representation of other healthcare professionals, including secondary care doctors with relevant experience, nurses, pharmacists, academic clinicians and other healthcare workers. Not surprisingly, two-thirds of participants reported an additional respiratory qualification or special interest in respiratory care, which may have affected generalisability, but only a few had a special interest in research.

While we received a large response rate for the initial survey of potential research questions, not all were able to participate in the subsequent rating rounds, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Relatively fewer family physicians and participants with special respiratory interests participated in the rating rounds, which may have affected the final priority order. However, the distribution of participants from low, medium and high-income settings remained similar throughout.

One of the objectives of this study was to cover the breadth of respiratory conditions relevant to primary care. The bottom-up approach adopted with the open-ended questions helped to identify all important conditions observed in practice, including TB, lung cancer, interstitial lung diseases and sleep apnoea. A thorough evidence review stage was added to ensure that questions were refined and validated against current evidence by academic subject experts, thus avoiding duplication, questions already researched, or those not feasible for research. Inevitably there may have been some subjectivity involved; however, they were given standard guidance with a structured proforma and several experts were involved in most topic areas. The list of research questions was then prioritised by the non-expert participants, thus ensuring wider views were obtained on the most important questions.

Furthermore, using qualitative methods to analyse participants’ responses in-depth enabled us to triangulate the e-Delphi prioritisation and introduced an additional perspective on respiratory research gaps. This helped to highlight important issues beyond specific respiratory conditions that could be helpful in improving the care of respiratory patients in primary care globally.

Unfortunately, due to limited time and resources, it was not feasible to involve members of the public and patient groups or other stakeholders within this study. Their views should now be sought to provide further insight and alternative perspectives and we welcome Brief Communications and Comment.

Finally, full generalisability cannot be ensured, as we were only able to accept participants who had access to the internet and could complete the survey in English (including through self-arranged translators), which could be more of a problem in the primary care setting compared with secondary care.

The implications of our prioritised research questions will be far-reaching. It is widely accepted that the only way to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, including a reduction in tobacco use, reduction in premature mortality from chronic respiratory diseases and improving wellbeing, is by orienting health systems towards primary care and supporting universal access25. However, this access needs to be to good quality primary healthcare26. Therefore, this study has identified clear knowledge gaps for primary care, which need to be addressed and tailored to the preferences of local primary care professionals.

Questions and themes elicited from this study can now be used to guide researchers and funders when planning research and allocating resources. Respiratory research has hitherto been relatively poorly funded, but it is clear from our work that more funding is urgently required and focussed on the greatest need. Our prioritised list of research questions generated by practising healthcare professionals ensures relevance and improves the chance of effective implementation. Research inspired by these priorities will contribute to the improvement in the respiratory health of patients in primary care, both locally and globally.

The requirement for prioritised respiratory research needs relevant to primary care is vital now more than ever10. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented pressure on healthcare systems globally and prompted a re-organisation of the healthcare landscape11. This has impacted the way primary healthcare including vaccination for, diagnosis and management of respiratory conditions, is being delivered worldwide, with the use of remote and telephone consultations increased substantially12. COVID-19 has introduced a significant impact on the core competencies of primary care, which is affecting the continuity of care and changing the way primary healthcare will be provided in the near and distant future14. As COVID-19 has created new opportunities and innovations in medical research15,16, it will be important to tailor prioritised primary care respiratory research needs to fit into this new era of medical research. It is crucial, therefore, to allow for any new and dynamic changes in primary care when shaping prioritised primary care respiratory research.

The findings of this study also suggest a need to invest in evidence implementation with the publication of locally relevant primary care guidance, supported by effective methods of translation into practice. This exercise has also been signposted to areas of training needs for primary care professionals.

Finally, addressing these key areas of research will have wider implications for primary care because many of the respiratory research needs are generalisable to other conditions.

In conclusion, this e-Delphi exercise provides a prioritised list of respiratory-related research questions, which can be used by funders and researchers to commission and conduct research studies relevant to primary care clinicians globally. The findings also emphasise the need for primary care relevant guidance supported by effective approaches to achieve implementation. By driving this research agenda, we anticipate a shift in research funding and activity to improve the respiratory health and healthcare of patients managed in primary care worldwide.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Soriano, J. B. et al. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3 (2020).

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Five insights from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31404-5 (2020).

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 (2020).

European Respiratory Society. in The European Lung White Book. Respiratory Health and Disease in Europe. Ch. 35. (European Lung Foundation, Sheffield, 2013).

Finley, C. R. et al. What are the most common conditions in primary care? Systematic review. Can. Fam. Physician 64(11), 832–840 (2018).

Pinnock, H. et al. The International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) Research Needs Statement 2010. Prim. Care Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00021 (2010).

Yoshida, S. Approaches, tools and methods used for setting priorities in health research in the 21st century. J. Glob. Health https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.06.010507 (2016).

Bousquet, J. et al. Prioritised research agenda for prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases. Euro. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00012610 (2010).

Vardavas, C. I. et al. H2020 funding for respiratory research: scaling up for the prevention and treatment of lung diseases. Euro. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01417-2019 (2019).

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 (2020).

Williams, S. et al. Respiratory research funding is inadequate, inequitable, and a missed opportunity. Lancet Respir. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30329-5 (2020).

IPCRG. Desktop helper 11 Remote consultations https://www.ipcrg.org/dth11https://www.ipcrg.org/aboutus (2021).

World Bank Data Team. New country classifications by income level: 2018–2019. (The World Bank Group, 2018).

Pinnock, H. et al. Prioritising the respiratory research needs of primary care: the international primary care respiratory group (IPCRG) e-Delphi exercise. Prim. Care Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00006 (2012).

Sumsion, T. The Delphi technique: an adaptive research tool. Br. J. Occup. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802269806100403 (1998).

Hsu, C. & Sandford, B. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract. Assessment, Res. Eval. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2070(99)00018-7 (2007).

Online Surveys. Jisc online survey tool. https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/ (2020).

Soriano, J. B. et al. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X (2017).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evauation. Global Burden of Disease Compare. (University of Washington, 2019).

Araújo, V., Teixeira, P. M., Yaphe, J. & Correia De Sousa, J. The respiratory research agenda in primary care in Portugal: a Delphi study. BMC Fam. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0512-1 (2016).

Masefield, S. et al. The future of asthma research and development: a roadmap from the European Asthma Research and Innovation Partnership (EARIP). Euro. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02295-2016 (2017).

Rudan, I. et al. Setting research priorities for global respiratory medicine within the national institute for health research (NIHR) global health research unit in respiratory health (RESPIRE). J. Glob. Health https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.08.020314 (2018).

Stephens, R. J. et al. Research priorities in mesothelioma: a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Lung Cancer https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.05.021 (2015).

NIHR. James Lind Alliance. https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/ (2020).

Hone, T., Macinko, J. & Millett, C. Revisiting Alma-Ata: what is the role of primary health care in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals? Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31829-4 (2018).

Ghebreyesus, T. A. How could health care be anything other than high quality? Lancet Glob. Health https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30394-2 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The IPCRG is very grateful to all the healthcare professionals across the world who took part in this e-Delphi survey, to LC for facilitating survey recruitment and to Neil Fitch for administrative assistance for the final report. IPCRG commissioned this work which was donated by all authors. IPCRG provided travel and administrative support and a free conference place to the lead researcher and incentivised responses by funding a prize draw for a free conference place for a forthcoming IPCRG conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.A. designed, conducted and analysed the study with supervision from R.J. A.B., Fv.G., J.K., K.L., C.N., I.T., S.W. and O.Y. advised on the protocol and materials. S.W. facilitated the recruitment and response of participants and advised on interpretation and write-up of the paper. P.A., K.L., R.J. and R.A. advised on the interpretation of qualitative component. P.A., A.B., I.B., Jv.B., N.C., A.D., Fv.G., M.E., S.H., A.K., B.K., K.L., C.N., C.M.N., E.M., L.M., S.P., H.P., D.P., D.R., S.S., J.C.S., B.S., S.J.S., S.T., I.T., A.T., D.W. and S.W. provided academic expertise in refining the research questions. A.A.A. and R.J. wrote the final draft with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.A. holds grants related to respiratory epidemiology from the NIHR. She chairs the NIHR Public Health Research Funding Committee. Jv.B. has received consultancy fees, honorarium and research funding from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Pill Connect, Teva and Trudell Medical to consult, give lectures, provide advice and conduct independent research, all paid to his institution. J.C.S. has in the last 3 years received payment for participating in educational activities from Boheringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Novartis and Mundipharma. R.J. reports grants from the NIHR and participation in a Boehringer Ingelheim primary care advisory board during this project. J.K. reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from Chiesi Pharmaceuticals, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from GSK, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants from MundiPharma, grants from TEVA, outside the submitted work, all paid to his institution; and J.K. holds 72.5% of shares in the General Practitioners Research Institute. K.L. has received personal fees for lectures and educational activities from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi and served on advisory boards arranged by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Boehringer Ingelheim. L.M. has received payment for participating in educational activities, consultancy, or support to attend clinical meetings from Hero España, Merck-Allergopharma, ALK-Abelló, Laboratorios Jofre-Roig, Laboratorios Leti, Faes Farma, Novartis, Inmunotek, GSK, and Alter. D.P. has board membership with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Circassia, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Thermofisher; consultancy agreements with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Theravance; grants and unrestricted funding for investigator-initiated studies (conducted through Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd) from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Circassia, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Respiratory Effectiveness Group, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Theravance, UK National Health Service; payment for lectures/speaking engagements from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyorin, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals; payment for the development of educational materials from Mundipharma, Novartis; payment for travel/accommodation/meeting expenses from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mundipharma, Mylan, Novartis, Thermofisher; funding for patient enrolment or completion of research from Novartis; stock/stock options from AKL Research and Development Ltd which produces phytopharmaceuticals; owns 74% of the social enterprise Optimum Patient Care Ltd (Australia and UK) and 74% of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd (Singapore); 5% shareholding in Timestamp which develops adherence monitoring technology; is peer reviewer for grant committees of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme, and Health Technology Assessment; and was an expert witness for GlaxoSmithKline. H.P. in the last 3 years was paid by Teva to write a piece on supported self-management for their website. Organisations with which she is involved, or conferences/meetings at which she has spoken receive multi-company sponsorship. D.R. has in the last 3 years received payment for participating in educational activities, consultancy or support to attend clinical meetings from: AZ,BI, GSK, Chiesi, Novartis, Trudell, Meda, Regeneron and Medscape. He is a board member of the Primary care and allied health section of the European Academy of Allergy and clinical Immunology and vice president of the Respiratory Effectiveness Group. B.S. has received honoraria for educational activities and lectures from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, MEDA and TEVA and has served on advisory boards arranged by AstraZeneca, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim and MEDA. S.S. has served as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Propeller Health, Sanofi, and Regeneron; and received a grant from Propeller Health. All payments were made to his university. A.T. has grants for respiratory research from AstraZeneca, Chiesi and CSL Behring, and has additional consultancy or honoraria for educational work for GSK and Boehringer Ingelheim. S.T. holds grants related to COPD and asthma from the NIHR. I.T. has in the last 3 years received payment for participating in educational activities, consultancy or received grants from: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and ELPEN. She is the Editor in Chief of the npjPCRM. O.Y. holds a grant related to respiratory health from the NIHR. A.B., R.A., A.A.A., D.A., I.B., N.C., A.D., M.E., Fv.G., S.H., A.K., B.K., D.K., E.M., C.Mc., C.N., S.P., S.J.S., D.W., S.W. and A.K.T. declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdel-Aal, A., Lisspers, K., Williams, S. et al. Prioritising primary care respiratory research needs: results from the 2020 International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) global e-Delphi exercise. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 32, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-021-00266-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-021-00266-4

This article is cited by

-

Recognising the importance of chronic lung disease: a consensus statement from the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (Lung Diseases group)

Respiratory Research (2023)

-

Improving Primary Healthcare Education through lessons from a flock of birds

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2023)