Abstract

Most patients with chronic respiratory disease live in low-resource settings, where evidence is scarcest. In Kyrgyzstan and Vietnam, we studied the implementation of a Ugandan programme empowering communities to take action against biomass and tobacco smoke. Together with local stakeholders, we co-created a train-the-trainer implementation design and integrated the programme into existing local health infrastructures. Feasibility and acceptability, evaluated by the modified Conceptual Framework for Implementation Fidelity, were high: we reached ~15,000 Kyrgyz and ~10,000 Vietnamese citizens within budget (~€11,000/country). The right engaged stakeholders, high compatibility with local contexts and flexibility facilitated programme success. Scores on lung health awareness questionnaires increased significantly to an excellent level among all target groups. Behaviour change was moderately successful in Vietnam and highly successful in Kyrgyzstan. We conclude that contextualising the awareness programme to diverse low-resource settings can be feasible, acceptable and effective, and increase its sustainability. This paper provides guidance to translate lung health interventions to new contexts globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) are a major burden to health worldwide, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) being the third leading cause of death1. The vast majority of deaths related to CRD occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)2,3,4. While the prevalence of major risk factors to CRD—smoking and household air pollution (HAP)—is commonly high in LMICs, means to combat the risks are low5,6,7,8,9,10. Preventing CRD is the most affordable and effective strategy for decreasing the burden4. This would involve solutions such as smoking cessation and providing alternatives for cooking and heating on solid fuels in poorly ventilated homes. However, for decades, implementation of such interventions in local communities has demonstrated to be challenging11,12,13,14.

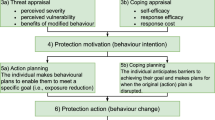

An important reason for implementation failure is the misalignment of local knowledge and beliefs with the interventions offered and their implementation strategies15,16,17,18,19. If there is no locally perceived need for change, motivation for behaviour change is low20,21. Particularly in rural areas of LMICs, awareness about CRDs and the risks of tobacco and biomass fuel smoke is low. COPD as a disease, and the implications of asthma, are often unknown to local community members, policy makers and health workers4,22. This affects the quality of care and prevents communities from taking simple steps to avoid smoke exposure5,23,24,25,26,27. In addition, the use of biomass fuels is determined by poverty28,29. Motivating low-income household to purchase cleaner stoves and fuels is generally beyond their means28,30,31. Therefore, for successfully reducing risk behaviour, preventive interventions are needed that understand and address these barriers to behaviour change.

An intervention to raise awareness about CRDs and empower communities with realistic measures to reduce exposure to risk factors was conducted in Uganda32. The programme was underpinned by the capability, opportunity, motivation—behaviour (COM-B) model. Changing behaviour of individuals, groups or populations involves addressing one or more of the COM elements33. By raising knowledge and awareness of CRD and the harms of smoke exposure (capability) and providing realistic, affordable solutions to prevent exposure (opportunity), participants were stimulated (motivation) to reduce risk behaviour (behaviour). This awareness programme had a cascading train-the-trainer structure and started with healthcare workers (HCWs) with medical knowledge, who then trained community health workers (CHWs) with limited medical knowledge, who trained their communities. CHWs were considered the key players in raising awareness. They are chosen from their own community and play a crucial role in providing primary healthcare in low-resource settings; often, they are the only ones available to provide direct medical assistance in their community34,35. The programme demonstrated to be feasible, acceptable and effective32. Potentially, this programme could be widely applicable to other settings across the world.

However, effectively translating evidence-based interventions to other settings is considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as among the biggest challenges of the twenty-first century36. Failure to adequately translate and implement interventions can seriously comprise their effectiveness37,38. Practical guidance on how to translate a preventive programme addressing awareness on CRD and empowering communities to change risk behaviour is unavailable. Therefore, our aim was to study the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of translating an awareness programme targeting risks to CRD to two completely different contexts in Kyrgyzstan and Vietnam and provide lessons learned from this process.

Results

Details on the awareness programme and the deployed implementation strategy are provided in Box 1. A structured evaluation of the programme’s feasibility, acceptability and fidelity is detailed in Table 1.

Feasibility

The awareness programme was implemented as planned, without delays within the 3-year timeline of the FRESH AIR (Free Respiratory Evaluation and Smoke-exposure reduction by primary Health cAre Integrated gRoups) project (Table 1). Costs remained within the budgeted €11,000 per setting, although there were local variations (Table 2). For example, travel costs were high in Kyrgyzstan, with rough mountainous terrains. In Vietnam, norms in the health infrastructure prescribed that all additional training time for health workers had to be financially compensated.

Fidelity

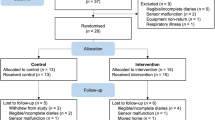

Generally, the steps of the programme were adhered to as intended (Fig. 1 and Table 1). We co-developed the local implementation strategy with local stakeholders, co-created the programme’s materials (Fig. 2) and completed a train-the-trainer cascade. We slightly deviated from the planned delivery method in Kyrgyzstan; the relatively long travel times due to rough terrains in Kyrgyzstan resulted in an adapted structure in our cascade.

Essential components of the implementation strategy

Adequate knowledge of the local context was essential to successful programme implementation. This included knowledge of the health and political infrastructure, to ensure embedment of the programme into it. For example, capitalising on the vital role of CHWs demonstrated to be an effective and sustainable delivery strategy. CHWs were already trusted by communities and trained to deliver knowledge; the programme simply additionally equipped them with relevant medical knowledge to spread. Adequate knowledge of the local context also included knowledge of local beliefs and behaviours regarding respiratory symptoms and risks. For example, a polite Vietnamese habit to invite a male stranger to a conversation is offering him a cigarette. The programme hence needed to address how to join a conversation without having to smoke the cigarette.

We also considered it crucial to collaborate with local authorities, promote community participation and engage local knowledgeable and influential stakeholders (Supplementary Methods). Engaging stakeholders from the beginning enabled us to learn about the local context and also created the sense of ownership needed for sustained use of the programme. Although the bureaucratic approval process of the programme’s materials by national authorities resulted in a delay of several months, this collaboration with local authorities was needed for a sustained implementation.

We did not reach consensus on the necessity to train through a full cascading structure. The local Kyrgyz team believed that omitting workstream 2 (Fig. 1) would increase implementation success, while the coordinating team had the impression that for efficiency and sustainability of the programme, preferably all workstreams should be involved.

Lastly, flexibility was an important component. Many important stakeholders or contextual factors only revealed themselves along the way; the programme and delivery should be highly adaptable to continue to promote compatibility with the context.

Effectiveness

On the immediate psychological capability level in the COM-B, the percentage of questions answered correctly on the knowledge questionnaire improved significantly among all groups in both countries (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Results). In Kyrgyzstan, knowledge was initially more limited, but improvements were larger. Notably, in Kyrgyzstan we did not assess the initial group of HCWs as this group included local FRESH AIR team members.

HW health worker (CHW and social worker), HCW healthcare worker, CHW community health worker. All differences between pre- and post-training scores were significant (P < 0.05; Wilcoxon signed-rank tests). In Kyrgyzstan, the ten HCWs were not included, as some members were part of the FRESH AIR team.

On the longer-term behavioural level, acceptability of the improved stoves was high: 100% of the stove users in Kyrgyzstan and 89.8% in Vietnam recommended the new stove to others. Stove stacking occurred in 15% of the Kyrgyz households and 85.5% of the Vietnamese39. In Vietnam, the improved cookstoves were often considered too small: 44% continued to use the traditional cookstove for cooking every day and 36% for several times a week.

Discussion

In this study, we translated an awareness programme on the risks of biomass fuel and tobacco smoke to lung health, proven effective in Uganda, to two completely different low-resource settings: Kyrgyzstan and Vietnam. We demonstrated that the implementation of the programme was highly feasible and acceptable in both new settings. It was highly effective in Kyrgyzstan and moderately effective in Vietnam. Essential determinants for implementation success were (1) adequate knowledge of the local context and embedding the programme into it (using existing health infrastructures), (2) collaborating with local influential stakeholders and motivating communities to actively participate and (3) flexibility throughout the process.

Other cascading train-the-trainer awareness programmes for lung health have previously demonstrated to be feasible in LMICs40,41. However, these studies mainly focussed on tobacco as a risk factor to lung health, while the need to address HAP is increasingly recognised42. Interestingly, these other programmes reported several essential factors of the implementation strategy comparable to those we had identified. Where we identified engaging influential and knowledgeable stakeholders, an Indian awareness programme on tobacco similarly defined the involvement of local role models (teachers) and leadership engagement (support from the school principals) as crucial40. Where we identified motivating the community, a PALSA study on CRD guidelines in South Africa reported actively involving participants in the delivery of the intervention41. Costs of these programmes were not reported, so cannot be compared. Both studies also reported the importance of compatibility of the intervention and implementation strategy with the local context, although they did not specifically emphasise the importance of embedding the programme into the local health infrastructures. A large overview of reviews on CHW programmes published in the Lancet Global Health in 2018 reported this embedment as a key recommendation for implementation success43.

We achieved statistically significant knowledge increases among all groups in both countries. The larger knowledge increase in Kyrgyzstan compared to Vietnam could be due to the lower baseline knowledge in Kyrgyzstan. Vietnam has had a longer tradition of patient education and patient self-management (and has established patient groups already decades ago). This may imply that awareness programmes could cover more advanced content in countries like Vietnam. Besides a higher increase in knowledge, also the acceptability and adequate use of cookstoves were higher in Kyrgyzstan compared to Vietnam after the awareness programme. This may indicate, in line with literature, that better knowledge on the risks of HAP to lung health is associated with higher success of clean cooking programmes15,16. Notably, rates for adequate adoption of the stoves were substantially higher in Kyrgyzstan compared to stove adoption rates from other studies. Adoption rates are often not reported in clean cookstove studies; if they are, it is commonly mentioned the rates are ‘strikingly low’, ‘disappointing’, or around 4–10%11,44. However, stove stacking occurred substantially more frequently in Vietnam in our study, suggesting that, besides knowledge, other causes also contribute to inadequate clean cooking practices. For example, characteristics of the stove are known to influence implementation success15,16; Vietnamese participants in the FRESH AIR stove programme considered their stove too small and continued to use their old one concurrently39. Hence, with many factors contributing to the adequate use of improved stoves, programme implementation should ideally go hand in hand with all favourable factors, such as favourable market developments and policies15,16. This gives this cascading train-the-trainer programme a particularly powerful potential when applied by policy makers, health workers and communities together, because then all different factors can be addressed simultaneously.

This study both aligns with the recent WHO guideline that emphasises on the role of CHWs in the prevention and treatment of (non-)communicable diseases35 and responds to the call to enhance focus on contexts during implementation45,46. Furthermore, we systematically applied and evaluated a uniform programme design in two completely different settings, enabling us to assess its wider applicability. This approach addresses the challenge of inconsistency in methodology and implementation assessment between training programmes for CHWs47. Another strength is the action research approach involving the whole system (from Ministry of Health to community), while generating real-world evidence. For example, the district health officers appointed the first HCWs to be trained. They supposedly selected the most capable and motivated HCWs, which is precisely what would happen in a non-study setting. Such an approach reduces selection bias and potential underestimations of the programme’s effect. Furthermore, the focus on implementation (fidelity) and its context—knowing what is ‘in the black box’—combined with effectiveness enabled us to relate the observed effect to the intervention with more confidence48,49. We are also among the few community-based implementation studies that included programme costs as an outcome50. The cascading train-the-trainer approach is designed to continue programme activities after the initial project has ended, thus contributing to the development of a sustainable system that builds knowledge and capacity among health workers and raises awareness in communities. As a limitation, our budget did not allow for observation of all implementation activities in vivo (precise number of delivered sessions, number of participants reached, etc.). Therefore, we relied on health workers’ self-reported implementation integrity. Social desirability might have tempted workers to over-report their implementation efforts51, possibly leading to an overestimation of fidelity. However, the number of completed knowledge questionnaires allowed us to triangulate and confirm the self-reported number of HCWs and CHWs trained and provide us with a minimum number of trained community members. Furthermore, although the effect was assessed at multiple levels in this study, each had its limitation. Validated questionnaires assessing knowledge about the risks of biomass and tobacco smoke did not exist to our knowledge. We therefore developed these questionnaires ourselves. In addition, the results from the questionnaires could be subject to selection bias. Also, although acceptability of the stoves was very high in both countries and stove stacking was particularly low in Kyrgyzstan39, we were unable to conclude whether these longer-term outcomes were causally related to the awareness programme. Many other factors are associated with adequate stove use15 and there was no control group. Tobacco-related behaviour change was not measured. Also, the financial barrier for behaviour change was less prominent in our study as the people received a small compensation for study participation (the price of the cheapest stove option in Vietnam or a stove donated by the World Bank in Kyrgyzstan). Therefore, conclusions on indications for effectiveness should be interpreted with caution.

Exposure to HAP and tobacco smoke continues to place a high burden on LMICs, not only through CRD but also through stroke, cardiovascular disease, ischaemic heart disease, pneumonia and lung cancer42,52. Beyond the health burden, there is a substantial socioeconomic burden of CRD in LMICs53. Effectiveness of previous lung health programmes is often hampered by implementation failure, further draining resource potential from already resource-limited settings and leading to poor health outcomes11. By demonstrating a feasible, acceptable and effective translation of an awareness programme in Uganda to two completely different settings—in Kyrgyzstan and Vietnam—we provide a potential guide for universal translation to other settings. The programme can be implemented on itself or, as applies to our FRESH AIR project, be an excellent starting point to prepare for smoking cessation programmes54 or clean cooking interventions39. This same implementation strategy of the programme could also be used to address other relevant health topics beyond lung health. We recommend to establish a relation with the community before implementing an awareness programme, for example by conducting a rapid assessment55 of the local context first. This will help to address the identified essential determinants for implementation success (adequate knowledge of the local context and embedding the programme into it, collaborating with local influential stakeholders and motivating communities to actively participate and flexibility).

To conclude, contextually translating a train-the-trainer awareness programme from Uganda to Kyrgyzstan and Vietnam, and potentially other low-resource settings, can be feasible, acceptable and effective for increasing awareness on lung health and its risk factors. Increased awareness empowers communities to take action to reduce exposure to biomass and tobacco smoke, which can ultimately lead to better lung health in low-resource settings.

Methods

Study design

This prospective implementation study was conducted between 2016 and 2018 within the FRESH AIR research project56. Reporting of this study was guided by the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (Supplementary Methods)57. The programme itself and the implementation strategy are detailed in Box 1, and the programme’s design is detailed in Fig. 1.

Setting

We purposively selected Kyrgyzstan and Vietnam, as they represented two distinct low-resource settings with a high prevalence of CRDs and exposure to biomass and tobacco smoke31,58. In the highlands of Kyrgyzstan, >95% of households use wood or dung as their main fuel for their stoves (for cooking and heating); in the lowlands, approximately 30% use wood or coal31,39. Tobacco consumption is 26% (50% for men, 4% for women)59. In the Long An province of Vietnam, 75% of the households use solid fuels (65% use wood) for cooking39. Their tobacco consumption is 23% (47% for men, 1% for women)59. Pre-FRESH AIR fieldwork31,60 had revealed poor awareness on CRD in these countries. The exact settings were based on opportunity and the relationship already established with communities during earlier work. Further information on the settings is detailed in Supplementary Methods.

Study population

Any HCW, CHW and community member was eligible to participate in the programme; there were no additional inclusion or exclusion criteria. The group of HCWs to initiate the train-the-trainer cascade was selected with help from locally influential stakeholders with expert knowledge of the context, such as district health officers. These HCWs then conveniently selected other HCWs or CHWs, usually within their vicinity. Subsequently, the CHWs trained (almost all) community members living in their village.

Outcomes

We considered translation of the programme ‘feasible’ when it could be implemented with reasonable effort, budget and time and ‘acceptable’ if those delivering or receiving the programme responded emotionally and cognitively collaborative61. ‘Fidelity’ was considered to be high if the steps in programme were adhered to as intended (Fig. 1). Effectiveness was assessed at multiple levels; the immediate effect on CRD-related awareness (psychological capability in the COM-B) was assessed by knowledge questionnaires. The longer-term effect was expressed in degree of acceptability of improved stoves distributed in a subsequent FRESH AIR programme and behaviour (adequate use of the stoves)39. In this latter programme, households could select a locally manufactured improved cookstove/heater that they considered most suitable.

Data collection and instruments

Data on the feasibility and acceptability of the programme, and lessons learned, were collected during face-to-face and online discussions throughout the entire implementation process. We discussed these topics until consensus was reached. The short-term effectiveness was assessed by a questionnaire for HCWs and one for both CHWs and community members. All HCWs and CHWs were invited to fill out the questionnaires as part of the training. Questionnaires contained several true/false/I-don’t-know statements relating to the programme’s content (Supplementary Methods). They were filled out before and after the training. Respondents were instructed to choose ‘true’/‘false’ when confident about an answer and to choose ‘I-don’t-know’ otherwise. The questionnaires were adapted according to lessons learned in Uganda32. They were translated to Russian and Vietnamese, respectively, back-translated to English, compared with the original versions and tailored accordingly. Acceptability and adequate use of improved stoves of the subsequent FRESH AIR programme were assessed by questionnaires and observations of stove stacking, respectively.

Analysis

Feasibility and acceptability of the programme, and lessons learned, were qualitatively analysed, guided by the modified Conceptual Framework for Implementation Fidelity62,63. This framework focusses on adherence to complex health interventions, potential moderators and identifying ‘essential components’ for achieving the intended outcome (Table 2, left column). Effectiveness on awareness was determined by changes in people’s mean score on the pre- and post-training knowledge questionnaire, analysed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (IBM SPSS Statistics version 25, Armonk, NY, USA). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Indications for longer-term behavioural effectiveness (acceptability and adequate use of improved stoves) were calculated using descriptive statistics.

Sample size and selection

We pragmatically aimed for 400 pre- and post-training community questionnaires. This number was chosen based on the maximum number of households that the budget allowed. Community members were randomly invited, stratified by gender, by the CHWs who gave the training. For the effect on acceptability and adequate use, 20 households in Kyrgyzstan and 76 in Vietnam were randomly invited in the stove programme.

Ethics

The study complied with all ethical regulations and was approved by the research ethical review board of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam (188/DHYD-HD;06/27/2016) and the National Center of Cardiology and Internal Medicine Ethics Committee in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan (5;03/03/2016). All participants with an improved stove provided written, informed consent before enrolment in the study. In case of illiteracy, the information was read to the participant and a thumb-print was provided instead. Other activities were within existing job descriptions (CHWs and HCWs) or regarded the attendance of routine educational activities upon personal initiative (community members).

Reflexivity

Our team was diverse in terms of gender, age, professional background and nationality, contributing to diverse perspectives and richer data. To avoid hierarchy being at play, we emphasised that every person’s input during evaluations was equally valuable.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data and meta-data will be available within a reasonable timeframe upon reasonable request.

Change history

20 October 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Global Burden of Disease - Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir. Med. 5, 691–706 (2017).

World Health Organization. Factsheet chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. https://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/en/ (2020).

World Health Organization. Factsheet asthma. https://www.who.int/respiratory/asthma/en/ (2020).

Forum of International Respiratory Societies. The Global Impact of Respiratory Disease 2nd edn (European Respiratory Society, Sheffield, 2017).

Beran, D., Zar, H. J., Perrin, C., Menezes, A. M., Burney, P. & Forum of International Respiratory Societies Working Group Collaboration. Burden of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and access to essential medicines in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Respir. Med. 3, 159–170 (2015).

Pleasants, R. A., Riley, I. L. & Mannino, D. M. Defining and targeting health disparities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 11, 2475–2496 (2016).

Torres-Duque, C. A. Poverty cannot be inhaled and it is not a genetic condition. How can it be associated with chronic airflow obstruction? Eur. Respir. J. 49, 1700823 (2017).

Brakema, E. A. et al. COPD’s early origins in low-and-middle income countries: what are the implications of a false start? npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 29, 6 (2019).

Sood, A. et al. ERS/ATS workshop report on respiratory health effects of household air pollution. Eur. Respir. J. 51, 1700698 (2018).

Townend, J. et al. The association between chronic airflow obstruction and poverty in 12 sites of the multinational BOLD study. Eur. Respir. J. 49, 1601880 (2017).

Brakema, E. A. et al. Let’s stop dumping cookstoves in local communities. It’s time to get implementation right. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 30, 3 (2020).

Dogar, O., Elsey, H., Khanal, S. & Siddiqi, K. Challenges of integrating tobacco cessation interventions in TB programmes: case studies from Nepal and Pakistan. J. Smok. Cessat. 11, 108–115 (2016).

Mendis, S. et al. Gaps in capacity in primary care in low-resource settings for implementation of essential noncommunicable disease interventions. Int. J. Hypertens. 2012, 584041 (2012).

Thomas, E., Wickramasinghe, K., Mendis, S., Roberts, N. & Foster, C. Improved stove interventions to reduce household air pollution in low and middle income countries: a descriptive systematic review. BMC Public Health 15, 650 (2015).

Puzzolo, E., Pope, D., Stanistreet, D., Rehfuess, E. A. & Bruce, N. G. Clean fuels for resource-poor settings: a systematic review of barriers and enablers to adoption and sustained use. Environ. Res. 146, 218–234. (2016).

Rosenthal, J. et al. Implementation science to accelerate clean cooking for public health. Environ. Health Perspect. 125, A3–A7 (2017).

Damschroder, L. J. et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 4, 50 (2009).

Nilsen, P. & Bernhardsson, S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19, 189 (2019).

Brakema, E. A. et al. Implementing lung health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a FRESH AIR systematic review and meta-synthesis. Eur. Respir. J. 56, 2000127 (2020).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211 (1991).

Hochbaum, G. M. Public Participation in Medical Screening Programs: A Sociopsychological Study (Public Health Service, PHS Publication 572, Washington, DC, 1958).

Mortimer, K., Cuevas, L., Squire, B., Thomson, R. & Tolhurst, R. Improving access to effective care for people with chronic respiratory symptoms in low and middle income countries. BMC Proc. 9(Suppl 10), S3 (2015).

Fullerton, D. G., Bruce, N. & Gordon, S. B. Indoor air pollution from biomass fuel smoke is a major health concern in the developing world. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102, 843–851 (2008).

World Health Organization. Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases: Guidelines for Primary Health Care in Low Resource Settings. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee (WHO, Geneva, 2012).

Perez-Padilla, R., Schilmann, A. & Riojas-Rodriguez, H. Respiratory health effects of indoor air pollution. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14, 1079–1086 (2010).

van Gemert, F. et al. Impact of chronic respiratory symptoms in a rural area of sub-Saharan Africa: an in-depth qualitative study in the Masindi district of Uganda. Prim. Care Respir. J. 22, 300–305 (2013).

Amegah, A. K. & Jaakkola, J. J. Household air pollution and the sustainable development goals. Bull. World Health Organ. 94, 215–221 (2016).

van Gemert, F. A. et al. The complications of treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in low income countries of sub-Saharan Africa. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 12, 227–237 (2018).

Landrigan, P. J. et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 391, 462–512 (2018).

Warwick, H. A. D. Joint statement WHO/UNDP: indoor air pollution-the killer in the kitchen. Indian J. Med. Sci. 58, 458–459 (2004).

Brakema, E. A. et al. High COPD prevalence at high altitude: does household air pollution play a role? Eur. Respir. J. 53, 1801193 (2019).

Jones, R., Kirenga, B., Buteme, S., Williams, S. & van Gemert, F. A novel lung health programme addressing awareness and behaviour-change aiming to prevent chronic lung disease in rural Uganda. Afr. J. Respir. Med. 14, 2–9 (2019).

Michie, S., Atkins, L. & West, R. The Behavioural Change Wheel (Silverback Publishing, Sutton, 2014).

Lehmann, U. & Sanders, D. Community health workers: what do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programs, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. https://chwcentral.org/resources/community-health-workers-what-do-we-know-about-them-the-state-of-the-evidence-on-programmes-activities-costs-and-impact-on-health-outcomes-of-using-community-health-workers/ (2007).

World Health Organization. WHO Guideline on Health Policy and System Support to Optimize Community Health Worker Programmes. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee (WHO, Geneva, 2018).

World Health Organization. Bridging the “know–do” gap - meeting on knowledge translation in global health. https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/training/capacity-building-resources/high-impact-research-training-curricula/bridging-the-know-do-gap.pdf (2006).

Durlak, J. A. & DuPre, E. P. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41, 327–350 (2008).

Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of Innovations 5th edn (Free Press, New York, 2003).

van Gemert, F. et al. Effects and acceptability of implementing improved cookstoves and heaters to reduce household air pollution: a FRESH AIR study. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 29, 32 (2019).

Nagler, E. M. et al. Designing in the social context: using the social contextual model of health behavior change to develop a tobacco control intervention for teachers in India. Health Educ. Res. 28, 113–129 (2013).

Bheekie, A. et al. The Practical Approach to Lung Health in South Africa (PALSA) intervention: respiratory guideline implementation for nurse trainers. Int. Nurs. Rev. 53, 261–268 (2006).

World Health Organization. Household air pollution and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/household-air-pollution-and-health (2018).

Cometto, G. et al. Health policy and system support to optimise community health worker programmes: an abridged WHO guideline. Lancet Glob. Health 6, e1397–e1404 (2018).

Brakema, E. A. et al. Implementing lung health interventions in low- and middle-income countries - a FRESH AIR systemaktic review and meta-synthesis. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00127-2020 (2020).

O’Donovan, J., O’Donovan, C., Kuhn, I., Sachs, S. E. & Winters, N. Ongoing training of community health workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic scoping review of the literature. BMJ Open 8, e021467 (2018).

Holman, D., Lynch, R. & Reeves, A. How do health behaviour interventions take account of social context? A literature trend and co-citation analysis. Health (Lond.). 22, 389–410 (2018).

Redick, C., Dini, H. & Long, L. The current state of CHW training programs in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia: what we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to do. http://www.chwcentral.org/sites/default/files/1mCHW_mPowering_LitReview_Formatted.compressed.pdf (2014).

Jean Shoveller, S. V., Ruggiero, EricaDi, Greyson, Devon, Thomson, Kim & Knight, Rodney A critical examination of representations of context within research on population health interventions. Crit. Public Health 26, 487–500 (2016).

Daivadanam, M. et al. The role of context in implementation research for non-communicable diseases: answering the ‘how-to’ dilemma. PLoS ONE 14, e0214454 (2019).

Wolfenden, L. et al. Identifying opportunities to develop the science of implementation for community-based non-communicable disease prevention: a review of implementation trials. Prev. Med. 118, 279–285 (2019).

Goenka, S. et al. Process evaluation of a tobacco prevention program in Indian schools–methods, results and lessons learnt. Health Educ. Res. 25, 917–935 (2010).

Carreras, G. et al. Burden of disease attributable to second-hand smoke exposure: a systematic review. Prev. Med. 129, 105833 (2019).

Brakema, E. A. et al. The socioeconomic burden of chronic lung disease in low-resource settings across the globe - an observational FRESH AIR study. Respir. Res. 20, 291 (2019).

McEwen, A. et al. Adapting Very Brief Advice (VBA) on smoking for use in low-resource settings: experience from the FRESH AIR project. J. Smok. Cessat. 14, 190–194 (2019).

Beebe, J. Basic concepts and techniques of rapid appraisal. Hum. Organ. 54, 42–51 (1995).

Cragg, L., Williams, S. & Chavannes, N. H. FRESH AIR: an implementation research project funded through Horizon 2020 exploring the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of chronic respiratory diseases in low-resource settings. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 26, 16035 (2016).

Pinnock, H. et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ 356, i6795 (2017).

World Health Organization. Air pollution in Viet Nam. http://www.wpro.who.int/vietnam/mediacentre/releases/2018/air_pollution_vietnam/en/ (2018).

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases (NCD country profile 2018) https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-profiles-2018/en/ (2018).

Nguyen, V. N., Huynh, T. T. H. & Chavannes, N. H. Knowledge on self-management and levels of asthma control among adult patients in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Int. J. Gen. Med. 11, 81–89 (2018).

Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M. & Francis, J. J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17, 88 (2017).

Carroll, C. et al. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement. Sci. 2, 40 (2007).

Hasson, H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement. Sci. 5, 67 (2010).

World Health Organization. Evaluating Energy and Health Interventions: A Catalogue of Methods (WHO, 2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues, who previously worked on this awareness programme with us in Uganda, for the important pre-work for the current study, in particular Bruce Kirenga, Shamim Buteme and Rupert Jones. We thank the International Primary Care Respiratory Group for introducing us to the primary care networks involved in this study and for their support on stakeholder engagement. We thank Job van Boven for critically reviewing the manuscript. We acknowledge REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) for facilitating a secure, web-based application for capturing research data. Lastly, we thank the local FRESH AIR teams, stakeholders, health workers and communities for their essential contributions to make this study possible. This study was funded by the EU Research and Innovation programme Horizon 2020 (Health, Medical research and the challenge of ageing) under grant agreement no. 680997, Trial register: TRIAL ID NTR5759, http://www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/admin/rctsearch.asp?Term=23332. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

F.v.G., in collaboration with S.W., T.S., P.A. and C.d.J., designed this study. E.A.B. provided input on the local context for the design based on explorative fieldwork. The organisation, including the training, was led by F.v.G., supported by E.A.B., and conducted by T.S., B.E., M.M. and A.T. in Kyrgyzstan and P.L.A., N.N.Q., L.H.T.C.H. and T.N.D. in Vietnam. The data were acquired by F.v.G., N.N.Q. and A.T. and analysed by E.A.B., F.v.G. and C.d.J. E.B. wrote the manuscript together with F.v.G.; C.d.J., R.v.d.K. and S.W. revised it. All authors gave input to the final version. E.A.B., F.v.G., R.v.d.K., S.W. and C.d.J. had the final responsibility for the decision to submit the study for publication. All authors had full access to the data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brakema, E.A., van Gemert, F.A., Williams, S. et al. Implementing a context-driven awareness programme addressing household air pollution and tobacco: a FRESH AIR study. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 30, 42 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-020-00201-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-020-00201-z