Abstract

The next generation of space-based experiments will go hunting for answers to cosmology’s key open questions which revolve around inflation, dark matter and dark energy. Low earth orbit and lunar missions within the European Space Agency’s Human and Robotic Exploration programme can push our knowledge forward in all of these three fields. A radio interferometer on the Moon, a cold atom interferometer in low earth orbit and a gravitational wave interferometer on the Moon are highlighted as the most fruitful missions to plan and execute in the mid-term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The standard cosmological model provides a simple framework to explain a variety of observations, ranging from sub-galactic scales to the size of the observable universe. Yet many open questions remain: the model relies on an unknown mechanism for the production of perturbations in the early universe, on an unknown matter component, generically referred to as dark matter, and on an unknown mechanism that leads to an accelerated expansion of the universe, generically referred to as dark energy.

The next generation of space-based experiments are our best chance of unveiling these mysteries. A united front of low earth orbit and lunar missions, as outlined in the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Human and Robotic Exploration (HRE)1, will break unprecedented ground on all of these fronts. Alongside the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna2, a radio interferometer on the Moon, a cold atom interferometer in low earth orbit and a gravitational wave interferometer on the Moon would provide a full-coverage approach to unravelling the key open questions in cosmology today.

In section “Key knowledge gaps” the key knowledge gaps in cosmology are highlighted, in section “Priorities for the space programme” specific suggestions for experiments that should be the priorities for ESA’s space programme and which questions they will answer are laid out, before concluding and discussing the future outlook in section “Future outlook and summary”.

Key knowledge gaps

Inflation

The theory of inflation is arguably the most promising model of the physics of the early universe3. The paradigm postulates that quantum fluctuations went on to seed the cosmological perturbations that we see imprinted on the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) and were the beginnings of all of the structure in the universe today. And yet, much remains to be understood about the properties of the quantum field that supposedly led to the initial period of exponential expansion of the universe. Whilst the paradigm is fully consistent with cosmological data4,5,6, we still currently lack direct smoking-gun evidence supporting it, as well as a specific model for how one or more scalar fields drove the expansion.

On large scales, k ~ 10−3 − 0.1 Mpc−1, observations of the CMB temperature anisotropies by Planck6 have confirmed to incredible precision that density perturbations were small (fluctuations of order 10−5) and almost scale-invariant. The simplest single-field, slow-roll models of inflation are able to describe this spectrum of the density perturbations. However, deviations from scale-invariance on small scales could indicate a more complicated model that exhibits a feature in the inflationary potential. Such models could have interesting observational signatures, such as ultra-compact mini-haloes7,8 or primordial black holes9. Furthermore, primordial non-Gaussianity has been constrained to be small, fNL,local = − 0.9 ± 5.1, on large scales10. This constraint has limited the viability of many models of inflation that predicted larger values of primordial non-Gaussianity, for example DBI inflation and EFT inflation11,12. However, reaching the fNL,local < 1 threshold will provide strong evidence that observations are not consistent with multi-field models of inflation13. The final piece of the puzzle can be provided by the tensor-to-scalar ratio, which is currently constrained to be less than 0.16, a measurement of which would indicate the energy scale at which inflation happened.

Dark matter

Similarly, the existence of dark matter is supported by a wide array of independent observations, but we still know very little about the fundamental nature of this elusive component of the universe. In the past four decades, a strong effort went into the search for a particular class of candidates: weakly interacting massive particles14. However, no experiment has yet found evidence for these particles, and attention has turned to different classes of dark matter candidates in regions of parameter space where they would have evaded strong constraints from direct detection before now, for example axion-like-particles (ALPs)15,16,17 or primordial black holes (PBHs)18.

Axion-like-particles are in particular a popular dark matter candidate15,16,17. The QCD (quantum chromodynamics) axion was first postulated in the 70s to solve the strong CP problem19. However, ALPs more generally, often motivated by string theories in which ultra-light particles are ubiquitous, display the qualities required to explain all or part of the dark matter. Whilst searches for the standard axion with a mass of order of a few hundred keV have yielded no detections, "invisible” axions with very small masses are still viable candidates. Search strategies vary depending on the mass of the axion, which can’t be theoretically predicted, but the most common approach is to probe their interactions with electromagnetic fields and constrain the axion-photon coupling20. Astrophysical observations are able to look for signatures of axion to photon conversion in the presence of electromagnetic fields, for example, by looking for such processes in the vicinity of the magnetosphere of neutron stars21,22,23, or their production in the solar core, triggered by X-rays scattering off electrons and protons in the presence of the Sun’s strong magnetic fields24.

For masses less than 1eV, axions are a sub-set of the broader class of ultra-light dark matter models, with masses down to (theoretically) 10−24 eV, although Lyman-alpha forest constraints have ruled out axion masses less than 2 × 10−20 eV25, see26 for a review. Ultra-light dark matter models postulate a new ultra-light boson, which displays wave-like properties on galactic scales, but behaves like cold dark matter on larger scales where the cold dark matter (CDM) paradigm has strong support from observations. The behaviour on galactic scales, due to the Bose-Einstein condensate which forms, can have interesting signatures that could explain small-scale problems with CDM27,28 and would have distinctive features for distinguishing between models such as fuzzy dark matter, self-interacting fuzzy dark matter and superfluid dark matter29,30.

Another promising candidate that received a lot of renewed attention after the LIGO/Virgo observations of order 10 solar mass binary black hole mergers is primordial black holes31,32,33. They are the only proposed explanation of dark matter that requires no new physics beyond the standard model, which makes them an attractive candidate. However, strong constraints have now been placed across the parameter space via microlensing, gravitational waves and CMB observations which have essentially ruled them out as making up the entirety of the dark matter budget in all but one window around an asteroid mass. See e.g., Ref. 34 for a review of current constraints. There is also the possibility of two-component dark matter models that include primordial black holes and another particle, with interesting signatures of interaction between the two35,36.

Dark energy

Dark energy is a generic term for the mechanism responsible for the observed accelerated expansion of the universe. One of the key questions that may bring us closer to the identification of dark energy is whether its energy density has remained constant throughout the history of the universe, as would be the case if it arises from the so-called vacuum energy, or whether it evolves with time, as appropriate for an evolving quantum field. See e.g., Ref. 37 for a review.

A diversified experimental approach involving astronomical surveys and gravitational waves searches are arguably our best hope to make progress in the search for smoking-gun evidence of inflation, identification of dark matter, and understanding of dark energy. We will highlight possibilities for future space-based experiments that can break new ground on these frontiers.

Priorities for the space programme

Space experiments may soon provide important clues on the nature of inflation, dark matter and dark energy. As an overview of the current context, we list in Table 1 some experiments that might in particular enable gravitational wave searches for signatures of dark matter and primordial gravitational waves with space-borne interferometers as well as indirect detection of dark matter and probing primordial fluctuations with Moon-based radio telescopes. We choose to focus on three key probes as most relevant in the framework of ESA’s Human and Robotic Exploration Directorate1 to address the knowledge gaps discussed above:

-

A.

a radio interferometer on the Moon (RIM)

-

B.

a space gravitational wave detector using cold atoms (AEDGE)

-

C.

a gravitational waves interferometer on the Moon (GWIM)

Radio interferometer on the Moon

The most relevant experiment for ESA’s Directorate of Human and Robotic Exploration is the radio interferometer on the Moon38,39,40,41. The rationale for this experiment is that placing a radio telescope on the far side of the Moon would give it access to wavelengths shorter than 30 MHz. Radiation at these frequencies is distorted or completely absorbed by the Earth’s ionosphere. An interferometer on the Moon will bypass this limitation, as well as shield the instruments from the background generated by terrestrial radio sources. Furthermore, the size of the array, which determines the resolution of the detector, is less restricted than an Earth-based detector like the Hydrogen Epoch of Reionization Array (HERA)42, the Low Frequency Array (LoFAR)43 or the Square Kilometre Array (SKA)44.

A radio telescope on the Moon would allow us to peer into the so-called dark ages of the universe45, i.e., the epoch between the emission of the CMB and the reionization of the universe, triggered by the formation of the first stars. By studying the redshifted 21-cm line absorption feature, we can obtain unprecedented information on the history of reionization, and search for the signatures of dark matter annihilation or decay by looking for specific forms of the absorption feature46,47.

Furthermore, a radio interferometer on the Moon could in principle have baselines as long as 300km, which would enable unprecedented access to information about very small scales48,49,50. Measuring the 21cm power spectrum would provide a tracer for the underlying dark matter power spectrum. This could unlock information about dark matter sub-structures, the existence of primordial black holes, and the validity of slow-roll inflationary models. Tomographic analysis will also enable information to be gathered at a range of redshifts, providing new insight into the evolution of our Universe between the time of the CMB and today.

Finally, a lunar radio telescope would allow us also to efficiently probe the so-called primordial non-gaussianity via the 21cm bispectrum51,52,53, which would provide a powerful test of the theory of inflation. 21cm observations will complement upcoming large-scale structure surveys which will help us to understand how structures are evolving, allowing for even more information to be extracted from the as yet un-probed region both in terms of redshift and access to small scales. 21cm observations from the Moon therefore add to the line of inquiry on all three fronts: inflation, dark matter and dark energy.

Arguably the largest challenge to overcome will be how to deal with extremely large foregrounds. They are expected to be 6 or 7 orders of magnitude larger than the signal being sought, and therefore systematics will need to be incredibly well understood. Extremely careful subtraction of galactic foregrounds54,55 will need to be performed so that any signal found in the data can be confidently interpreted56,57,58.

Cold atom interferometer

The direct detection of gravitational waves (GW) with LIGO/Virgo, that led to the Nobel prize for Physics in 2017, has opened new opportunities for cosmology. The space interferometer LISA has been selected to be ESA’s third large-class mission, and it is scheduled to be launched in 2034. Experience with the electromagnetic spectrum shows the importance of measurements over a range of frequencies, and we note that there is a gap between the frequencies covered by LIGO/Virgo, as well as proposed detectors Einstein Telescope and Cosmic Explorer on Earth, and LISA in space, in the deci-Hz band.

A promising candidate to explore this frequency band is the AEDGE mission concept59, which is based on novel quantum technology utilising Cold Atom (CA) techniques. Gravitational waves alter the distance between the cold atom clouds as they pass through the interferometer.

AEDGE will be able to probe the gravitational waves due to coalescing intermediate mass black holes with masses 100 − 105 M⊙. This could shed light on the existence of intermediate black holes, and their potential role as seeds for the growth of supermassive black holes60. Additionally, black holes in the pair-instability mass gap will enter the deci-Hz range. If this gap is populated then it will motivate a deeper understanding of supernova collapse, or the need to invoke alternative mechanisms for producing such large black holes such as hierarchical mergers61,62,63. Improved constraints on order 100M⊙ primordial black holes should also be possible, which would complement constraints from the CMB on this mass range64.

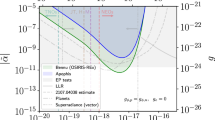

AEDGE can also probe a wide array of dark matter candidates. Scalar field dark matter, for instance, causes quantities such as the electron mass and the fine structure constant to oscillate with frequency and amplitude determined by the dark matter mass and local density. This leads to variation in the atomic transition frequencies, which imprint on the relative phase difference between cold atom clouds that atom interferometers measure.

Proposed AEDGE sensitivities will enable the coupling between scalar dark matter and electrons, photons or via the Higgs-portal to be probed with up to 10 orders of magnitude improvement, with respect to current constraints from MICROSCOPE65, on mass ranges between 10−18 and 10−12eV. Other couplings can also be probed, for example the axion-nucleon coupling for axion-like DM lighter than 10−14eV, or the coupling between a dark vector boson and the difference between baryon and lepton number66,67.

Furthermore, AEDGE offers a new channel for probing strong gravity regimes, where any deviations from general relativity are most likely to be noticeable. For example, precise measurements of post-Newtonian parameters would offer powerful probes of the predictions of general relativity and searches for deviations due to, for example, a graviton mass68. Comparing measurements in different frequency ranges will also make possible sensitive probes of Lorentz invariance69.

An opportunity to learn about the nature of dark matter from gravitational wave signals can also be realised by observations of coalescing black holes in the deci-Hz band. Intermediate mass black holes (103 − 105M⊙) and primordial black holes (of any mass) may be surrounded by dense dark matter spikes70,71. If these black holes form binaries with a much lighter companion, i.e., intermediate and extreme mass ratios (q = m2/m1 < 10−2.5), then the dark matter may imprint a dephasing on the gravitational waveform of the inspiralling binary. The amount of dephasing could teach us something about the nature of the dark matter surrounding the black holes, for example whether it’s cold and collisionless, or whether it’s an ultra-light scalar field. LISA will have sensitivity to such effects for larger mass systems72,73,74, future ground-based gravitational wave observatories will have sensitivity to low-mass systems, and an experiment such as AEDGE could bridge the gap to cover the entire frequency range and promote multi-band searches for the same signal. The gravitational wave signal could also be accompanied by an electromagnetic counterpart that might provide information about an environment involving dark matter if the particle is able to convert to radiation or interact with it in some way like it does in the case of, for example, axions.

Possible non-black hole binary cosmological targets for the deci-Hz band include GWs from first-order phase transitions in the early Universe, e.g., during electroweak symmetry breaking in modifications of the Standard Model with additional interactions, or during the breaking of higher gauge symmetries75. The deci-Hz frequency range could also probe different parameter ranges for such transitions, and combining measurements with those by other experiments like LISA or LIGO/Virgo could help unravel different contributions, e.g., from bubble collisions, sound waves and turbulence76,77. Another cosmological target for the deci-Hz band is the possible GW spectrum produced by cosmic strings78. In standard cosmology this spectrum would be almost scale-invariant, but there could be modifications due to a non-standard evolution of the early Universe. A detection or constraint on such observables could additionally provide clues as to the nature of dark matter, especially in the case of ultra-light dark matter particles which are expected to be produced alongside GWs from phase transitions in the early Universe and topological defects such as cosmic strings.

As outlined in the Cold Atom in Space Community Roadmap79, AEDGE, its pathfinder experiments, and other cold-atom experiments in space would also be able to make sensitive measurements relevant to several other aspects of fundamental physics, including the gravitational redshift, the equivalence principle, possible long-range fifth forces80,81, variations in fundamental constants and popular models of dark energy82.

With the AION experiment in the UK83, the MAGIS experiment in the US84, the MIGA experiment in France85, the ZAIGA experiment in China86, as well as the proposed European ELGAR project87, there is already a large programme of terrestrial cold atom experiments in place. These experiments serve as terrestrial pathfinders for a large-scale mission like AEDGE, and it would be important to complement those with a dedicated technology development programme to pave the way for space-based cold atom pathfinder experiments. First, dedicated pathfinders could be hosted at the International Space Station, building the foundation of a medium-class mission. This could then lead in the long-term to a large-class mission such as AEDGE to explore the ultimate physics potential of the deci-Hz band.

A gravitational waves interferometer on the Moon

In addition to a cold atom interferometer such as AEDGE, a lunar-based gravitational wave (GW) interferometer is ideal for probing GW frequencies in the range between deci-Hz to 5 Hz, which is where both Earth- and space-based detectors have less sensitivity88,89. Preliminary estimates suggest that such an instrument would allow us to trace the expansion rate of the universe up to redshift z ~ 3, test General Relativity and the standard cosmological model up to redshift z ~ 100, and probe the existence of primordial black holes, as well as dark matter in neutron star cores90,91.

Future outlook and summary

We have outlined recommendations for how the future experiments in ESA’s Human and Robotic Exploration Directorate fit into a strategy for answering the key fundamental questions in cosmology that we have highlighted in Table 1. These experiments will operate from either low earth orbit or the Moon, and are ambitious plans which should take place in the middle term, to give time for pathfinders and terrestrial experiments to pave the way for the development of the necessary technologies to make these moonshot missions possible. With many complementarities between experiments, European Space Agency’s (ESA) Human and Robotic Exploration programme has the potential to make dramatic and perspective-changing discoveries in cosmology and astroparticle physics.

References

European Space Agency. European Space Agency Agenda 2025. https://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/ESA_Agenda_2025_final.pdf (2021).

Amaro-Seoane, P. et al. Laser interferometer space antenna. https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.00786 (2017).

Guth, A. H. Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Phys. Rev. D. 23, 347–356 (1981).

Kogut, A. et al. First-year wilkinson microwave anisotropy probe (WMAP) observations: Temperature-polarization correlation. Astrophysical J. Suppl. Ser. 148, 161–173 (2003).

Hinshaw, G. et al. First-year wilkinson microwave anisotropy probe (WMAP) observations: data processing methods and systematic error limits. Astrophysical J. Suppl. Ser. 148, 63–95 (2003).

Collaboration, P. Planck 2018 results. Astron. Astrophys. 641, A10 (2020).

Aslanyan, G. et al. Ultracompact minihalos as probes of inflationary cosmology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 141102 (2016).

Bringmann, T., Scott, P. & Akrami, Y. Improved constraints on the primordial power spectrum at small scales from ultracompact minihalos. Phys. Rev. D 85, 125027 (2012).

García-Bellido, J. & Morales, E. R. Primordial black holes from single field models of inflation. Phys. Dark Universe 18, 47–54 (2017).

Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. IX. Constraints on primordial non-Gaussianity. Astron. Astrophys. 641, A9 (2020).

Chen, X. Primordial non-gaussianities from inflation models. Adv. Astron. 2010, 1–43 (2010).

Renaux-Petel, S. Primordial non-gaussianities after planck 2015 : an introductory review. Comptes Rendus Phys. 16, 969–985 (2015).

Byrnes, C. T. & Choi, K.-Y. Review of local non-gaussianity from multifield inflation. Adv. Astron. 2010, 1–18 (2010).

Schumann, M. Direct detection of WIMP dark matter: concepts and status. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 46, 103003 (2019).

Choi, K., Im, S. H. & Shin, C. S. Recent progress in the physics of axions and axion-like particles. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 71, 225–252 (2021).

Ringwald, A. Axions and axion-like particles. https://arxiv.org/abs/1407.0546 (2014).

Irastorza, I. G. & Redondo, J. New experimental approaches in the search for axion-like particles. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 102, 89–159 (2018).

Bertone, G. & Tait, T. M. P. A new era in the search for dark matter. Nature 562, 51–56 (2018).

Chadha-Day, F., Ellis, J. & Marsh, D. J. E. Axion dark matter: What is it and why now? https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.01406 (2021).

Semertzidis, Y. K. & Youn, S. Axion dark matter: How to see it? https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.14831 (2021).

Witte, S. J., Noordhuis, D., Edwards, T. D. & Weniger, C. Axion-photon conversion in neutron star magnetospheres: the role of the plasma in the goldreich-julian model. Phys. Rev. D. 10.1103/PhysRevD.104.103030 (2021).

Hook, A. & Huang, J. Probing axions with neutron star inspirals and other stellar processes. J. High Energy Phys. 2018, 36 (2018).

Foster, J. W. et al. Extraterrestrial axion search with the breakthrough listen galactic center survey. https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.08274 (2022).

Moriyama, S. et al. Direct search for solar axions by using strong magnetic field and X-ray detectors. Phys. Lett. B 434, 147–152 (1998).

Rogers, K. K. & Peiris, H. V. Strong bound on canonical ultralight axion dark matter from the lyman-alpha forest. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 071302 (2021).

Ferreira, E. G. M. Ultra-light dark matter. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.03254 (2020).

Popolo, A. D. & Delliou, M. L. Small scale problems of the ΛCDM model: a short review. Galaxies 5, 17 (2017).

Bullock, J. S. & Boylan-Kolchin, M. Small-scale challenges to the ΛCDM paradigm. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 55, 343–387 (2017).

Du, X., Behrens, C. & Niemeyer, J. C. Substructure of fuzzy dark matter haloes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 465, 941–951 (2017).

Khoury, J. Dark matter superfluidity. SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes 42 10.21468/SciPostPhysLectNotes.42 (2022).

Bird, S. et al. Did LIGO detect dark matter? Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 201301 (2016).

Sasaki, M., Suyama, T., Tanaka, T. & Yokoyama, S. Primordial black hole scenario for the gravitational-wave event GW150914. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 061101 (2016).

Sasaki, M., Suyama, T., Tanaka, T. & Yokoyama, S. Primordial black holes—perspectives in gravitational wave astronomy. Classical Quant. Grav. 35, 063001 (2018).

Green, A. M. & Kavanagh, B. J. Primordial Black Holes as a dark matter candidate. J. Phys. G 48, 043001 (2021).

Adamek, J., Byrnes, C. T., Gosenca, M. & Hotchkiss, S. WIMPs and stellar-mass primordial black holes are incompatible. Phys. Rev. D 100, 023506 (2019).

Bertone, G., Coogan, A. M., Gaggero, D., Kavanagh, B. J. & Weniger, C. Primordial black holes as silver bullets for new physics at the weak scale. Phys. Rev. D 100, 123013 (2019).

Mortonson, M. J., Weinberg, D. H. & White, M. Dark energy: a short review. https://arxiv.org/abs/1401.0046 (2014).

Aminaei, A. et al. Basic radio interferometry for future lunar missions. In 2014 IEEE Aerospace Conference, 1–19 (IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Society, 2014). Eemcs-eprint-24892; 2014 IEEE Aerospace Conference; Conference date: 01-03-2014 Through 08-03-2014.

Furlanetto, S. et al. Astro 2020 Science White Paper: Fundamental Cosmology in the Dark Ages with 21-cm Line Fluctuations. arXiv 10.48550/arXiv.1903.06212 (2019).

Burns, J. O. et al. Dark cosmology: investigating dark matter & exotic physics in the dark ages using the redshifted 21-cm global spectrum. https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.06147 (2019).

Duke, M., Mendell, W. & Roderts, B. Lunar bases and space activities of the 21st century. Strategies for A Permanent Lunar Base 57–68 (The Lunar and Planetary Institute, 1985).

DeBoer, D. R. et al. Hydrogen epoch of reionization array (HERA). Publ. Astronomical Soc. Pac. 129, 045001 (2017).

van Haarlem, M. P. et al. Lofar: the low-frequency array. AA 556, A2 (2013).

Dewdney, P. E., Hall, P. J., Schilizzi, R. T. & Lazio, T. J. L. W. The square kilometre array. Proc. IEEE 97, 1482–1496 (2009).

Koopmans, L. et al. Peering into the dark (ages) with low-frequency space interferometers. https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.04296 (2019).

Valdes, M., Ferrara, A., Mapelli, M. & Ripamonti, E. Constraining dark matter through 21-cm observations. Monthly Not. R. Astron. Soc. 377, 245–252 (2007).

Short, K., Bernal, J. L., Raccanelli, A., Verde, L. & Chluba, J. Enlightening the dark ages with dark matter. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2020, 020–020 (2020).

Bernal, J. L., Raccanelli, A., Verde, L. & Silk, J. Signatures of primordial black holes as seeds of supermassive black holes. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2018, 017–017 (2018).

Cole, P. S. & Silk, J. Small-scale primordial fluctuations in the 21 cm Dark Ages signal. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 501, 2627–2634 (2021).

Mena, O., Palomares-Ruiz, S., Villanueva-Domingo, P. & Witte, S. J. Constraining the primordial black hole abundance with 21-cm cosmology. Phys. Rev. D. 100, 043540 (2019).

Pillepich, A., Porciani, C. & Matarrese, S. The bispectrum of redshifted 21 centimeter fluctuations from the dark ages. Astrophys. J. 662, 1–14 (2007).

Muñ oz, J. B., Ali-Haïmoud, Y. & Kamionkowski, M. Primordial non-gaussianity from the bispectrum of 21-cm fluctuations in the dark ages. Phys. Rev. D 92, 083508 (2015).

Meerburg, P. D. et al. Primordial non-gaussianity. https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.04409 (2019).

Bernardi, G. et al. Foregrounds for observations of the cosmological 21 cm line. Astron. Astrophys. 500, 965–979 (2009).

Bernardi, G. et al. Foregrounds for observations of the cosmological 21 cm line. Astron. Astrophys. 522, A67 (2010).

Pober, J. C. et al. The importance of wide-field foreground removal for 21 cm cosmology: a demonstration with early MWA epoch of reionization observations. Astrophys. J. 819, 8 (2016).

Lucas Makinen, T. deep21: a deep learning method for 21 cm foreground removal. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 081 (2021).

Liu, A., Tegmark, M., Bowman, J., Hewitt, J. & Zaldarriaga, M. An improved method for 21-cm foreground removal. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 398, 401–406 (2009).

El-Neaj, Y. A. et al. AEDGE: Atomic experiment for dark matter and gravity exploration in space. EPJ Quantum Technol. 7, 6 (2020).

Latif, M. A. & Ferrara, A. Formation of Supermassive Black Hole Seeds. Vol. 33 (Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, 2016).

Di Carlo, U. N. et al. Binary black holes in the pair instability mass gap. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 497, 1043–1049 (2020).

Mehta, A. K. et al. Observing intermediate-mass black holes and the upper stellar-mass gap with LIGO and virgo. Astrophys. J. 924, 39 (2022).

Gerosa, D. & Fishbach, M. Hierarchical mergers of stellar-mass black holes and their gravitational-wave signatures. Nat. Astron. 5, 749–760 (2021).

Poulin, V., Serpico, P. D., Calore, F., Clesse, S. & Kohri, K. CMB bounds on disk-accreting massive primordial black holes. Phys. Rev. D 96, 083524 (2017).

Bergé, J. et al. MICROSCOPE mission: first constraints on the violation of the weak equivalence principle by a light scalar dilaton. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 141101 (2018).

Graham, P. W., Kaplan, D. E., Mardon, J., Rajendran, S. & Terrano, W. A. Dark matter direct detection with accelerometers. Phys. Rev. D. 93, 075029 (2016).

Poddar, T. K., Mohanty, S. & Jana, S. Vector gauge boson radiation from compact binary systems in a gauged Lμ - Lτ scenario. Phys. Rev. D 100, 123023 (2019).

Will, C. M. Bounding the mass of the graviton using gravitational-wave observations of inspiralling compact binaries. Phys. Rev. D. 57, 2061–2068 (1998).

KosteleckÃoe, V. A. & Mewes, M. Testing local lorentz invariance with gravitational waves. Phys. Lett. B 757, 510–514 (2016).

Eda, K., Itoh, Y., Kuroyanagi, S. & Silk, J. New probe of dark-matter properties: gravitational waves from an intermediate-mass black hole embedded in a dark-matter minispike. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 221101 (2013).

Eda, K., Itoh, Y., Kuroyanagi, S. & Silk, J. Gravitational waves as a probe of dark matter minispikes. Phys. Rev. D 91, 044045 (2015).

Kavanagh, B. J., Nichols, D. A., Bertone, G. & Gaggero, D. Detecting dark matter around black holes with gravitational waves: effects of dark-matter dynamics on the gravitational waveform. Phys. Rev. D 102, 083006 (2020).

Coogan, A., Bertone, G., Gaggero, D., Kavanagh, B. J. & Nichols, D. A. Measuring the dark matter environments of black hole binaries with gravitational waves. Phys. Rev. D. 105, 043009 (2022).

Ng, K. K., Isi, M., Haster, C.-J. & Vitale, S. Multiband gravitational-wave searches for ultralight bosons. Phys. Rev. D 102, 083020 (2020).

Zhou, R., Bian, L., Guo, H.-K. & Wu, Y. Gravitational wave and collider searches for electroweak symmetry breaking patterns. Phys. Rev. D 101, 035011 (2020).

Jinno, R. & Takimoto, M. Gravitational waves from bubble collisions: an analytic derivation. Phys. Rev. D 95, 024009 (2017).

Galtier, S. & Nazarenko, S. V. Direct evidence of a dual cascade in gravitational wave turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 131101 (2021).

Zhou, R. & Bian, L. Gravitational waves from cosmic strings and first-order phase transition. https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.13872 (2020).

Alonso, I. et al. Cold atoms in space: Community workshop summary and proposed road-map. https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.07789 (2022).

Battelier, B. Exploring the foundations of the physical universe with space tests of the equivalence principle. Exp. Astron. 51, 1695–1736 (2021).

Elder, B. et al. Chameleon dark energy and atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. D 94, 044051 (2016).

Sabulsky, D. O. et al. Experiment to detect dark energy forces using atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 061102 (2019).

Badurina, L. et al. AION: an Atom Interferometer Observatory and Network. JCAP 05, 011 (2020).

Abe, M. et al. Matter-wave atomic gradiometer interferometric sensor (magis-100). Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 044003 (2021).

Canuel, B. et al. Exploring gravity with the MIGA large scale atom interferometer. Sci. Rep. 8, 14064 (2018).

Zhan, M.-S. et al. ZAIGA: Zhaoshan long-baseline atom interferometer gravitation antenna. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D. 29, 1940005 (2020).

Canuel, B. et al. ELGAR – a European Laboratory for Gravitation and Atom-interferometric Research. Class. Quantum Gravity 37, 225017 (2020).

Lafave, N. L. & Wilson, T. L. The role of the moon in gravitational wave astronomy. In Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, vol. 23, 751 (LPSC, 1992).

Jani, K. & Loeb, A. Gravitational-wave lunar observatory for cosmology. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 044 (2021).

Dasgupta, B., Laha, R. & Ray, A. Low mass black holes from dark core collapse. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 141105 (2021).

Dasgupta, B., Gupta, A. & Ray, A. Dark matter capture in celestial objects: light mediators, self-interactions, and complementarity with direct detection. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2020, 023 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the European Space Agency for the opportunity to contribute this review article. P.S.C. acknowledges funding from the Institute of Physics, University of Amsterdam.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.B. and O.L.B. wrote the ESA science community white paper related to this topic, which P.S.C. adapted to form this perspective piece.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertone, G., Buchmueller, O.L. & Cole, P.S. Perspectives on fundamental cosmology from Low Earth Orbit and the Moon. npj Microgravity 9, 10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-022-00243-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-022-00243-2