Abstract

The development of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a life-threatening inflammatory bowel disease affecting preterm infants, is connected with gut microbiota dysbiosis. Using preterm piglets as a model for preterm infants we recently showed that fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from healthy suckling piglet donors to newborn preterm piglets decreased the NEC risk. However, in a follow-up study using donor stool from piglets recruited from another farm, this finding could not be replicated. This allowed us to study donor-recipient microbiota dynamics in a controlled model system with a clear difference in NEC phenotype. Preterm piglets (n = 38) were randomly allocated to receive control saline (CON), or rectal FMT using either the ineffective (FMT1) or the effective donor stool (FMT2). All animals were followed for four days before necropsy and gut pathological evaluation. Donor and recipient colonic gut microbiota (GM) were analyzed by 16 S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics. As expected, only FMT2 recipients were protected against NEC. Both FMT groups had shifted GM composition relative to CON, but FMT2 recipients had a higher lactobacilli relative abundance compared to FMT1. Limosilactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus crispatus strains of FMT recipients showed high phylogenetic similarity with their respective donors, indicating engraftment. Moreover, the FMT2 group had a higher lactobacilli replication rate and harbored specific glycosaminoglycan-degrading Bacteroides. In conclusion, subtle species-level donor differences translate to major changes in engraftment dynamics and the ability to prevent NEC. This could have implications for proper donor selection in future FMT trials for NEC prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a devastating intestinal inflammation primarily affecting infants born preterm with an incidence of up to 7%1,2. First reported in the early 1800s3, NEC has been intensively investigated but the underlying etiology is only partially understood1. In the neonatal period, the combination of impaired host antimicrobial defense mechanisms and gut dysbiosis (presence of opportunistic pathjogens and absence of commensals) might initiate a lethal hyperinflammatory reaction in the gut mucosa4,5,6. The preterm gut microbiome (GM) is often dominated by Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae7,8 and large-scale metagenomic studies have shown increased Proteobacteria9 and bacterial replication rates of Enterobacteriaceae prior to NEC incidence10. Although no single microbe has consistently been reported as a direct cause, accumulated evidence strongly indicates that gut microbial dysbiosis is an important risk factor for NEC.

Indeed, numerous GM-targeted interventions have been tested to prevent NEC. Examples include the use of prophylactic peroral aminoglycosides which reduces NEC incidence but is not considered feasible due to the risk of antimicrobial resistance and other potential side effects11. Prophylactic probiotic supplementation appears to reduce NEC incidence with few side effects12 and is routinely used in preterm infants, although the optimal combination of bacterial strains, dose, and timing is unknown. Regardless, the NEC incidence rate of 5–10% for very-low-birth-weight infants as well as the 10–30% mortality rate has not improved significantly the past 20 years2,13.

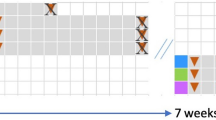

Through restoring the microbial diversity in the gastrointestinal tract, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been widely and effectively used to treat recurrent Clostridoides difficile infection (rCDI), showing high cure rates independent of specific donors14,15. However, FMT therapies targeting inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have shown discrepant clinical efficacy associated with the fecal donors16,17,18,19. Formula-fed preterm piglets display most clinical and pathological features of human NEC from feeding intolerance and bloated abdomen to intestinal necrosis and peritonitis20. This makes preterm piglets an appropriate model for microbial interventions in preterm neonates. Previously we have shown that rectal FMT can significantly reduce NEC incidence in preterm piglets while modulating the GM and host immune response with reduced mucosal proinflammatory TLR4 signaling21. Accordingly, using comparable donor material we failed to reproduce the NEC-reducing effect of FMT in a follow-up experiment. This led us to hypothesize that NEC prevention by FMT depends on the donor microbiome characteristics. In this controlled experiment, we randomly allocated preterm pigs to receive FMT from either of the two fecal donors or sterile saline (as illustrated in Fig. 1). To compare gut microbial responses and investigate engraftment patterns, we characterized the gut microbiota of donors and recipients using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics.

Fecal donor material was obtained from 2 different groups of term piglets (Donor 1 and 2) and rectally administered to preterm piglets born at 90% gestational age on one and two days of life. The preterm piglets were euthanized on day 5 of life. Respectively n = 13, 13, 12 for FMT1, FMT2 and CON. FMT1 rectal FMT with Donor 1, FMT2 rectal FMT with Donor 2, CON rectal FMT with sterile saline as control. The completed graphic was created with BioRender.com in an academic license (Supplementary Information).

Results

Donor-dependent host response existed in recipient piglets

FMT from Donor 2 significantly reduced the NEC incidence (CON vs. FMT2, 42 vs 0%, p = 0.0149, Fisher’s exact test), whereas FMT from Donor 1 only resulted in a non-significant NEC reduction (Fig. 2a). The pathological severity of FMT2 piglets decreased across all gut segments (Supplementary Fig. 1a), resulting in a significant reduction in pathological severity in FMT2 piglets relative to CON (Fig. 2b). Moreover, only FMT2 had reduced intestinal permeability as indicated by a lower urinary lactulose-mannitol ratio relative to CON piglets (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, FMT2 piglets showed reduced diarrhea severity for the duration of the study (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and had higher daily weight gain relative to FMT1 (Fig. 2d), while the digestive capacity of proteins (Fig. 2e) and carbohydrates (Fig. 2f) tended to be higher relative to CON. Gut histological evaluation showed no distinct change between treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. 1c–f). However, linear regression analysis suggested that histological data was strongly related to NEC severity, where myeloperoxidase (MPO) score in the colon and bacterial adhesion score explained most variance with R2 values larger than 0.5 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

FMT2 piglets showed superior survival and development status with lower NEC incidence (a) and necrosis severity (b) and improved gut barrier (c), daily weight gain (d), and digestive enzyme excretion (e, f). The label of * represents adjusted p < 0.05. Except for NEC incidence (two-sided Fisher’s exact test), the statistical difference was determined by Tukey’s post hoc test. Except for LM ratio and growth rate, n = 13, 13, 12, respectively, for FMT1, FMT2, and CON. For LM ratios, respectively n = 8, 8, 5 while n = 12, 12, 8 for growth rate. In boxplots, the inner fences are depicted as error bars. FMT1 rectal FMT with Donor 1, FMT2 rectal FMT with Donor 2, CON rectal FMT with sterile saline as control, NEC necrotizing enterocolitis, LM ratio urinary lactulose-mannitol ratio, SI DPPIV dipeptidyl-peptidase IV activity in the small intestine, SI Maltase maltase activity in the small intestine.

Fecal microbiota transplantation shifted the recipient gut microbiota in a donor-dependent manner

To determine GM changes induced by rectal FMT, we applied prokaryotic-specific 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing as well as broader profiling with shotgun metagenomics. The early-life GM of preterm pigs contained more Proteobacteria but fewer Bacteroidetes when compared to the composition of both donors (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The genus-level microbial composition of the two donors was quite similar (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c), despite resulting in two distinct phenotypes in the recipients. All recipients including FMT2 piglets had lower microbial Shannon diversity in the colon when compared to either of the two donors. However, the FMT2 group showed significantly higher gut microbial richness than FMT1 and CON (Fig. 3a, b). Both sequencing methods indicated that the GM of FMT2 piglets significantly differed from FMT1 and CON (Fig. 3c, d, Table 1). Donor and sow (maternal) effects were the two main independent factors affecting GM structure, which explained 15.4% and 6.4% of the total variance in a db-RDA model (Fig. 3e). NEC status explained only 5.8% and 4.1% of GM variation on unweighted UniFrac and binary Jaccard metrics, profiled by amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Shannon index calculated from 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (a) and Shotgun metagenomics (b); Unsupervised PCoA plots based on weighted UniFrac (c) and Bray Curtis dissimilarity metrics (d), and the db-RDA biplot showing the variance explained by FMT and SOW and the scaled loadings of core species (mean relative abundance > 1%) (e). The labels of * and ** represent adjusted p < 0.05 and 0.01 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test for Shannon index and PERMANOVA for beta diversity). Respectively n = 13, 13, 12 for FMT1, FMT2 and CON. In boxplots, the inner fences are depicted as error bars. FMT1 rectal FMT with Donor 1, FMT2 rectal FMT with Donor 2, CON rectal FMT with sterile saline as control, NEC necrotizing enterocolitis, 16S rRNA 16S ribosome RNA gene amplicon sequencing, Shotgun Shotgun metagenomics.

Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcaceae dominated the neonatal GM of preterm piglets. Distinct increases in lactobacilli and Streptococcus were observed in the colon samples of both FMT groups relative to CON (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). Db-RDA analysis revealed that Limosilactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus amylovorus and Streptococcus gallolyticus contributed most of the variation induced by FMT (Fig. 3e). We adopted DESeq2 to identify species differentially abundant between treatment groups. Besides the prevalence of lactobacilli and Streptococcus spp., we found significant reductions in Enterobacter cloacae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus orisratti, Clostridioides difficile and Enterococcus faecium in the gut of FMT2 piglets relative to CON (Fig. 4). In the colon samples of FMT1 piglets, we observed a distinctly decreased abundance of Lmb. reuteri, Lb. amylovorus, Ligilactobacillus agilis and Subdoligranulum variabile, but the higher relative abundance of Staph. aureus, E. faecium, and Strep. orisratti (FMT1 vs FMT2, adjusted p < 0.05, Wald test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction).

Differentially abundant core species (relative abundance > 1% among at least 10% of samples) are shown. The label of * represents adjusted p < 0.05 (Wald test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction). Respectively n = 13, 13, 12 for FMT1, FMT2 and CON. FMT1 rectal FMT with Donor 1, FMT2 rectal FMT with Donor 2, CON rectal FMT with sterile saline as control, NEC necrotizing enterocolitis. FMT, Fecal Microbiota Transplant.

Engrafted lactobacilli strains differed according to the respective donors

The relative abundance of lactobacilli increased in colon samples of both FMT treatment groups, but also distinctly differed in between (Fig. 5a). Lb. amylovorus, Lb. crispatus and Lmb. reuteri were the predominantly detected lactobacilli species and were found in the donors as well (Fig. 5b). The Lmb. reuteri and Lb. crispatus strains in the recipients showed different donor sources when we aligned their phylogenetic marker genes (Fig. 5c). The functional difference of engrafted lactobacilli strains was compared using PanPhlAn, and 798 gene families for Lmb. reuteri and 432 for Lb. crispatus were found to be different between the strains from FMT1 and FMT2 piglets (p < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test). These genes were associated with ABC transporters, fatty acid biosynthesis, amino acid biosynthesis/metabolism, and drug resistance (Supplementary Data 1 and 2).

The relative abundance (a) and dominant species (b) of lactobacilli, and strain tracking of Lmb. reuteri and Lb. crispatus by StrainPhlAn (c). Lactobacilli with minimum mean relative abundance of 1% are shown. The labels of *, ** and *** represent adjusted p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction). Respectively n = 13, 13, 12 for FMT1, FMT2 and CON. In boxplots, the inner fences are depicted as error bars. FMT1 rectal FMT with Donor 1, FMT2 rectal FMT with Donor 2, CON rectal FMT with sterile saline as control, 16S rRNA 16S ribosome RNA amplicon sequencing, Shotgun Shotgun metagenomics.

Shifted gut microbiota composition was linked to gastrointestinal improvements

In addition to the donor-dependent changes in the recipient GM, the altered microbial composition was associated with gastrointestinal improvements by FMT. Using NEC, diarrhea severity and histological data as indicators of gastrointestinal health, we conducted Pearson’s correlation analysis between the abundance of the core GM species and clinical variables. The abundances of Cl. difficile, C. perfringens and E. faecium positively correlated with NEC severity, MPO level and CD3+ cell density in the colon as well as bacterial adhesion score in the small intestine (Pearson’s coefficient > 0.4). Although we did not detect a direct correlation between lactobacilli and NEC severity, the diarrhea severity negatively correlated with Lmb. reuteri, Lgb. agilis and Subdo. variabile relative abundance (Fig. 6).

The core microbiome is used for correlation analysis (relative abundance > 1% among at least 10% of samples). The average NEC and diarrhea severity are taken as the indicators for gastrointestinal health, together with histological evaluation including goblet cell density, CD3+ cell density, and MPO score in colon and FISH score in the small intestine. The correlations are shown with absolute values of coefficients higher than 0.2. NEC necrotizing enterocolitis, MPO myeloperoxidase.

Furthermore, the shifted microbial structure led to microbial communities of differential functional capacities. We established a non-redundant pig GM gene catalog, annotated by the KEGG gene database. DESeq2 was adopted to identify differentially enriched KEGG modules between treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. 5). Compared with CON, the gut inhabitants in FMT2 piglets displayed distinct genetic enrichment involved in threonine (M00018), lysine (M00526, M00527), and acetate (M00579) biosynthesis. However, FMT1 piglets had fewer microbial genes encoding these functional capacities in the colon, but more genes associated with staphyloferrin B biosynthesis (M00875). Meanwhile, pathogenetic signatures from Salmonella enterica (M00856) and Escherichia coli (M00542) were detected in colon samples of FMT2 and FMT1 but rarely in that of CON (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Genome-resolved analysis revealed donor-specific patterns in recipient piglets

To conduct genome-resolved analysis between donors, we refined the output of four automatic binning tools (metabat2, maxbin2, concoct, vamb) and reconstructed in total 583 medium-quality MAGs including 394 high-quality ones (completeness > 90% and contamination < 5%). Different binning strategies were compared, and the subject-specific binning strategy generated more high-quality MAGs than binning on co-assemblies (Supplementary Fig. 6). To mitigate mis-mapping bias caused by sequence homology, we used the breadth of coverage > 50% to determine the presence of a MAG in the donors. Under this criterion, piglets receiving FMT from the two donors had 199 shared MAGs, while 53 MAGs were unique to Donor 2 and 57 were unique to Donor 1. The bacterial replication rate was estimated by the sequencing coverage trend across the genome using iRep. The lactobacilli population displayed higher iRep values in the gut of FMT2 piglets relative to FMT1, while in CON iRep values were difficult to determine, due to the low relative abundance of lactobacilli (Fig. 7a). Among 309 MAGs present in donors, 74 MAGs showed differential relative abundance in the gut of FMT1 and FMT2 recipients (adjusted p < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction). Consistently with the mapping-based method, most of these MAGs belonged to lactobacilli and Streptococcus (Fig. 7b). The MAGs of Lmb. reuteri, Lb. amylovorus and Subdo. variable were mainly recovered in the colon samples from FMT2 piglets and Donor 2. Lb. crispatus, Lmb. vaginalis and Strep. gallolyticus were detected in both recipient groups but the MAGs differed according to their respective donors. Using the microbial markers provided by PhyloPhlAn, we assessed the phylogenetic relationship of the recovered MAGs. No donor-specific phylogenetic separation of the MAGs was found (Supplementary Fig. 7).

The replication rate of lactobacilli genomes (a) and the abundance of engrafted MAGs (b) displayed donor-dependent differences. The functional similarity of donor-specific MAGs is shown by the db-RDA triplot with the scaled loadings of the glycosaminoglycans-degradation modules (c). Host-virus pairs are validated with spacers, where the colors of flows suggest the host taxonomy (d). The labels of * and ** represent adjusted p < 0.05 and 0.01 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction). Respectively n = 13, 13, 12 for FMT1, FMT2 and CON. In boxplots, the inner fences are depicted as error bars. FMT1 rectal FMT with Donor 1, FMT2 rectal FMT with Donor 2, CON rectal FMT with sterile saline as control.

The functional similarity of donor-specific MAGs was compared based on the presence of KEGG modules in the genomes (Fig. 7c). The Donor 2-specific MAGs possessed more KEGG modules of heparan sulfate degradation (M00078, adjusted p < 0.005, Fisher’s exact test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction), keratan sulfate degradation (M00079, adjusted p < 0.01, Fisher’s exact test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction) and carbohydrate metabolism genes associated with the pentose phosphate pathway and galactose (Supplementary Data 3). Heparan and keratan sulfate are ubiquitous glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in mammalian tissue. The two GAG-degradation modules were predominately harbored by Bacteroides e.g., B. vulgatus in Donor 2 (Breadth of coverage > 90%, Supplementary Data 4). The Donor 1-specific MAGs on the other hand showed functional enrichment in staphyloferrin B biosynthesis and drug-resistant efflux pump QacA, which likely originated from Staphylococcus aureus (Supplementary Data 3).

The viral genomes were categorized based on their presence in the respective donors. All vOTUs were found in the colon of recipients and approximately 95% detected in the donors, of which over 80% were shared by both donors (Supplementary Fig. 8). We compared the genetic similarity of the recovered vOTUs against the vConTACT2 reference phage genomes. A considerable number of vOTUs in the donors clustered with Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Escherichia, Klebsiella, and Salmonella) and lactobacilli phages (Supplementary Fig. 8), corresponding to the adequate host abundance there. Using the spacer sequences, 92 host-phage matches were found between the MAGs and vOTUs, with Escherichia, Streptococcus and lactobacilli phages being most prevalent (Fig. 7d). Most host-phages identified in the pairs were shared by the two donors, except for unique phages predicted to attack Escherichia, Faecalicoccus and Clostridiales, which were only harbored by Donor 2.

Discussion

FMT exhibits high cure rates (90% on average) when used to treat the overgrowth of one specific pathogen, Cl. difficile, in the gut22. The success of FMT in rCDI treatment is not affected by a specific donor23. In a cohort compromising of 1999 FMT recipients and 28 donors, the rCDI cure rate was found to be high for all donors22. Encouraged by this overwhelming success, researchers have extended the use of FMT in a range of diseases characterized by GM dysbiosis e.g., IBD24 and metabolic syndrome25. Contrarily, the super donor phenomenon appears to exist in FMT treatments of these diseases e.g., Crohn’s disease16, ulcerative colitis17,18, irritable bowel syndrome19 and type-2 diabetes25. We utilized a preterm piglet model to evaluate gut responses to FMT using two phenotypically similar donors and with a particular focus on NEC development. Using a randomized setup, preterm piglets from two litters were allocated into three treatment groups, FMT1, FMT2, and CON. Recipients of the superior donor feces (FMT2) showed no NEC cases relative to 23% NEC incidence in recipients of the inferior donor feces and 42% in the CON group. Relative to infants, NEC-like lesions of preterm piglets manifest more frequently in the ventricle and colon, and less so in the small intestine. As these gut segments are more densely populated with microbes, this could indicate that the microbial contribution to NEC development is more pronounced in piglets than infants. This model discrepancy should be considered when interpreting the data. Different animal models exist for studying NEC. Importantly, unlike the murine NEC model26, extra physical manipulations e.g., the cold or hypoxic stress was not introduced to induce NEC-like pathology27. Although the histological assessment did not show statistical differences between treatment groups, the NEC severity was strongly and positively correlated to the gastrointestinal MPO and FISH scores, as well as the CD3 + cell proportion (Supplementary Fig. 2). Besides, FMT2 piglets also exhibited improved gut function (e.g., barrier, digestion) and body weight gain relative to CON. Using a randomized design, each piglet was treated in single incubators separately to avoid possible confounding factors except the FMT donor. All in all, our data suggests the chosen donor is a determinant factor for the protective effect of FMT on preterm neonates.

A superior donor appears to be more essential for FMT use in multifactorial diseases such as IBD and NEC, which result from complex interactions between host immune response, host genetics, GM, and exogenous intake e.g., formula feeding. Gut dysbiosis is implicated in the etiology and development of these diseases but none is solely induced by overgrowth of one specific microbe as rCDI. Given the existing redox potentials in gut28, a preterm GM is usually characterized by relatively low microbial diversity and prolonged dominance of facultative anaerobes e.g., Enterobacter, Enterococcus, and Staphylococcus, but delayed colonization by obligate anaerobes e.g., Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides29. This might provide gastrointestinal conditions associated with high NEC risk. We noticed that the donor-dependent phenomenon was not only reflected in the host response but also in the shifted recipient GM. In the present study, the two different donors were the most important factor contributing to GM differences in the recipients, with an effect size 2–3 times higher than the second most important factor, namely the litter (Supplementary Fig. 4). Higher Shannon index and more lactobacilli but less Cl. difficile, C. perfringens and E. faecium were found in the colon of FMT2 piglets.

Pathogen resistance is a noted advantage provided by GM30, which is also expected to provide protection against NEC31. Using Pearson’s correlation analysis, we found the abundance of Cl. difficile and C. perfringens and E. faecium positively linked with increased pathological severity and gut inflammation. Although we cannot causally link these species with NEC, we still note that efficient FMT inhibited the colonization of opportunistic pathogens. Consistently, functional profiling of GM indicated the FMT2 group contained fewer microbial genes encoding staphyloferrin synthesis, but more genes associated with lysine and acetate biosynthesis in the gut. Staphyloferrin is a high-affinity siderophore excreted by S. aureus to acquire iron to proliferate32. This mechanism is employed by some pathogens to scavenge sequestrated iron from the host and plays an essential role in bacterial virulence33. The reduction of these genetic elements suggested a declined risk of invasive gastroenteritis by Staph. aureus. Lysine, considered to be an essential amino acid, has recently been found to be produced partially by GM and then absorbed by host34. GM-mediated amino acid metabolism could be essential for neonates given the high accretion of body protein. A disrupted GM, e.g., suppressed by antibiotics, is linked to decreased protein synthesis rate in the gut35. Orally administrated lysine is also reported to ameliorate diarrhea symptoms in a rodent model36. Besides, the superior Donor 2 resulted in recipient GM with a higher capacity for acetate production, which is in accordance with the reported increase of short-chain fatty acid production using the same donor21.

Donor species richness is reported to determine FMT success among IBD patients16. In this study, the two donor microbiotas had similar alpha diversity and composition but resulted in differential gut microbiome composition and clinical response among recipients. Hence, microbial richness alone may not ensure FMT efficiency. Our data suggest that even strain-level variation may play an important role and affect donor bacterial engraftment. The two donors had comparable lactobacilli composition; however, lactobacilli colonized recipients in a donor-dependent manner. Phylogenetic analysis indicated different strains of Lmb. reuteri and Lb. crispatus were present in the donors. Identified by PanPhlAn, Lmb. reuteri strains from the superior donor (Donor 2) conferred more drug resistance genes such as colistin resistance protein EmrB. The strain-level variation likely made the Lmb. reuteri from Donor 2 more robust to cope with environmental challenges and led to a higher replication rate of lactobacilli in the gut of FMT2 piglets. Besides, MAG-level analysis indicated that Donor 2 contained specific Bacteroides e.g., B. vulgatus conferring heparan and keratan sulfate utilization genes. Heparan and keratan sulfate are two major classes of GAGs on mammalian epithelial cells, which play a fundamental role in mutualistic bacteria adhesion37,38 as well as bacterial infectivity of pathogens. Given the high genome coverage of these MAGs solely in the superior donor, we suspected the GAG-degrading Bacteroides might competitively exclude other GAG-binding pathogens39. Bacteroides are considered as next-generation probiotics for their ubiquitous GAG-degrading capacity37 and production of anti-inflammatory lipopolysaccharide40. Gavage of B. vulgatus is reported to alleviate murine endotoxemia by suppressing lipopolysaccharide production in the gut41. One multi-donor FMT trial has also indicated that increased Bacteroides in donor stool is associated with ulcerative colitis remission in recipients42.

Although rectal FMT showed promising properties in terms of preventing NEC, we also noticed increased pathogenetic signatures from Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica in the guts of recipients. This highlights the risk of potential transmission of infectious agents during FMT, which also explains previously high sepsis cases through oral administration21. Even though the transferred enteropathogens did not violate the preventive effect of rectal FMT here, they might become a risk factor43. Interestingly, metagenomic data confirmed the existence of adequate Enterobacteriaceae phages in the donors, which may act in balancing the microbiome composition through host-phage interactions. In a follow-up study, we showed that fecal filtrate transplantation could also protect preterm pigs from NEC, reduce opportunistic pathogen (e.g., Klebsiella spp.) colonization, and restore the balance of gut bacteria and phages44.

Methods

Animals and experimental setup

Experimental animal procedures were approved by the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate (2014-15-0201-00418). Thirty-eight crossbred piglets (Landrace × Yorkshire × Duroc) from two sows were delivered at 90% gestion (106 days) and fitted with an oro-gastric feeding tube and an arterial catheter inserted through the transected umbilical cord. Animals were housed separately in heated incubators (37–38 °C) with oxygen supply as previously outlined27. To account for the lack of transplacental immunoglobulin transfer, passive immunization was provided by arterial infusion of maternal plasma (16 ml/kg) and followed by parenteral nutrient supplementation (2–4 ml/kg/h, Kabiven, Vamin, Fresenius-Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany). Increasing volumes of infant formula (3–12 ml/kg/3 h) were administered in the feeding tube from birth to day 5.

Fecal microbiota transplantation

Two donor solutions were prepared from pooled colon content of four 10-day-old healthy pigs (Landrace × Yorkshire × Duroc) from two different specific pathogen-free (SPF) herds and born by multiparous sows (Fig. 1). Donor herd 1 was reared without antibiotics and donors were non-siblings, whereas donor herd 2 was conventionally reared, selected donors derived from the same litter, and all piglets were given a long-lasting Amoxicillin injection on the day of birth. All donor pigs were of an age-adequate size and with no history of infectious disease or signs of diarrhea. The donor pigs were euthanized, and colon content was collected, pooled, diluted 1:1 in 20% sterile glycerol, and stored at −80 °C21. All individual donor samples were free of Vancomycin-resistant enterococci and extended-spectrum β-Lactamase-producing coliforms when assessed by plating on Vancomycin-containing Slanetz-Bartley agar and Cefotaxime-containing MacConkey agar, respectively45. Before use, donor feces were thawed and diluted to a working concentration of 0.05 g/ml after filtration through a 70-µm cell strainer to remove macroscopic debris. Animals were stratified by gender and birth weight and randomly allocated to receive rectal administration of 0.5 ml working fecal solution from donor herd 1 (FMT1, n = 13), donor herd 2 (FMT2, n = 13), or sterile physiological saline (CON, n = 12). The FMT was administered twice on days 1 and 2 (one dose per day).

Clinical evaluation and tissue collection

Animals were monitored by experienced personnel throughout the experiment, and weight and stool patterns were recorded daily. Predetermined humane endpoints resulting in immediate euthanasia included signs of systemic illness such as lethargy, respiratory distress, and hypoperfusion). On day 5, the remaining animals were euthanized with a lethal dose of intracardiac barbiturate under deep anesthesia. Three hours before scheduled euthanasia, animals received a 15 ml/kg oro-gastric bolus of lactulose and mannitol (5/5% w/v) to measure intestinal permeability by urinary recovery. After exposing the abdominal cavity, urine was collected by bladder puncture for lactulose and mannitol measurement46. Gross pathological evaluations of the stomach, small intestine, and colon were performed by blinded reviewers according to a validated six-grade NEC scoring system21. NEC was defined as pathology grade 4 (extensive hemorrhage) in at least one gastrointestinal segment, and both incidence and severity (maximum score across all three gut segments) were reported. Small intestine and colon tissues were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin-embedded for histological assessment of bacterial adhesion by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), goblet cell fraction determination by Alcian Blue-Periodic acid-Schiff (AB-PAS) staining, and T-cell and myeloid cell areas by CD3 and MPO immune staining, respectively21. The FISH signal was evaluated by a blinded investigator using an ordinal grading system (0–3) based on signal density and dissemination in the mucosa. Due to the high background signal, automated MPO image analysis was not possible. Instead, MPO stained tissue was evaluated using a composite ordinal grading system (0–7) consisting of cell signal density (0–3) and the extent of MPO-associated mucosa inflammation (0–4). Mucin (AB-PAS) and CD3 relative areas were quantified by image analysis using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Representative histological staining pictures for piglets with and without NEC in the small intestine are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. Relative to healthy (no NEC) segments, NEC samples showed eroded small intestines in a loose and incomplete epithelial structure, increased MPO activity, and bacterial aggregation in the epithelial lining. Frozen tissues were homogenized in 1.0% Triton X-100 and the homogenates were assayed for brush-border disaccharidase (lactase, maltase, and sucrase) and peptidase activities (aminopeptidases N, aminopeptidase A and dipeptidyl-peptidase IV) using a colorimetric method46. The enzyme activities were expressed per gram of wet intestine (proximal, middle, and distal), and one unit (U) of enzymatic activity represented the hydrolysis of 1 µmol substrate per minute at 37 °C. Colon content was collected and snap-frozen for 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics.

DNA extraction and high-throughput sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from colon content using Bead-Beat Micro AX Gravity Kit (A&A, Gdynia, Poland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified for prokaryotic community characterization by NextSeq 150 bp pair-end sequencing47 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Technical replicates of donors were sequenced for amplicon sequencing. For broader profiling, 150 bp pair-end metagenomic shotgun sequencing on Illumina Novaseq 6000 was conducted after PCR-free library preparation with KAPA HyperPrep Kit (KAPA Biosystems). The shotgun sequencing was carried out by a commercial sequencing service provider (Admera Health, South Plainfield, NJ, USA).

Bioinformatic processing of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing data

The raw reads of amplicon sequencing were merged and trimmed to construct zero-radius operational taxonomic units (zOTUs) after removing chimeras48,49. The Greengenes database (v13.8) was used as an annotation reference. Post analysis and visualization were performed using Phyloseq50. Raw zOTU data was rarefied at 11 000 counts to calculate Shannon diversity index and beta-diversity metrics (weighted and unweighted UniFrac distance metrics). For both amplicon and shotgun profiling, the genus-level taxonomic names of taxa previously belonging to the genus Lactobacillus were updated manually following the recently updated taxonomy for Lactobacillaceae by Zheng et al.51 When referring jointly to genera previously belonging to the genus Lactobacillus the term “lactobacilli” is used (as recommended in the announcement51).

Bioinformatic processing for shotgun metagenomics

The bioinformatic workflow for shotgun metagenomics and integration with clinical data followed the strategy illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 10, and GNU-parallel was used to execute jobs in parallel52. Quality control of raw reads utilized Read_qc module within metaWRAP53. PhiX174 control and host genome (Sus scrofa 11.1, GCA_000003025.6) were removed using BMTagger and followed by Trim Galore for adapter and quality trimming, resulting in total 317 Gb clean data with a mean depth of 7.9 Gb per sample. The taxonomic profiling was done with Kaiju54 through protein-translated search against all prokaryotic and viral proteins in the NCBI_nr database plus microbial eukaryotic proteins (2019.6) under the default settings. Kaiju-based results were summarized at phylum, genus, and species level to calculate the respective diversity index and GM abundance, and the unclassified reads (Mean: 4.4%, Min: 0.8%, Max: 20.2%) were removed. The abundance matrix was normalized with Hellinger’s transformation before calculating the binary Jaccard and Bray Curtis distance metrics. For de novo assembly, each sample was individually assembled with metaWRAP53 Assembly module under –use-metaspades mode55, and then all the reads were co-assembled under –use-megahit mode56.

Metagenome functional annotation

The individually- and co-assembled contigs were concatenated together for open reading frames (ORFs) prediction with MetaGeneMark57 (v3.38), followed by clustering with Linclust58 under the criteria of 95% identity and overlap > 90% (-min-seq-id 0.95, -c 0.9) to construct a non-redundant gene catalogue. Short ORFs with a length of less than 100 bp were removed with seqkit59. The remaining ORFs were annotated against the KEGG gene database (2019.05.15) using GhostKOALA60. Clean reads were mapped back to the non-redundant gene set using bwa61 and samtools62 to calculate gene abundance. Reads with mapping quality better than 30 were kept and each pair of reads mapped to the same gene counted once.

Metagenome-assembled genomes reconstruction

To avoid fragmented assemblies of similar strains63, individually assembled long scaffolds (>2000 bp) were binned with maxbin2, concoct, and metabat2 in the metaWRAP53 Binning module. Putative bins from each sample were dereplicated using dRep64 (-comp 50 -con 5 –sa 0.99) to generate a medium-quality bin set (completeness > 50% and contamination < 5%) for each binner. Two-step bin refinement was adopted with the Bin_refinement module to combine results from the three binners and another deep-learning-based binner Vamb (v2.1)65. For Vamb, genomic bins of more than 200 000 base pairs were included. This subject-specific binning strategy extracted more complete bins compared with direct binning on co-assemblies (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The abundance of refined bins was determined by the Quant_bins module in metaWRAP53. The ORFs of refined metagenomic assembled genomes (MAGs) were called using prodigal66 under metagenomic mode (-p meta) and annotated by the KEGG gene database using GhostKOALA60. The breadth of coverage (covered percentage of genomic size) of MAGs in each sample was estimated by coverm (https://github.com/wwood/CoverM). The MAGs with a breadth of coverage > 50% were considered “detected” in one sample. Based on the breadth of coverage information, MAGs were grouped as “Donor1-specific”, “Donor2-specific”, “Donor shared” and “Recipients specific”. The linkage and taxonomy of the MAGs were assessed by MAGpy67 to integrate results from PhyloPhlAn, Checkm, and blast against the UniProt database.

To estimate the bacterial replication rate (as a surrogate measure of growth rate), the generated MAGs were first dereplicated using dRep63 under 99% clustering threshold (the ANImf algorithm) and 25% minimum coverage overlap, and iRep68 values were calculated based on the mapped reads against the representative MAGs. Default settings for iRep were adopted.

Strain tracking of Lactobacillus crispatus and Limosilactobacillus reuteri

Lb. crispatus and Lmb. reuteri strains from the 2 donors were tracked using clade-specific marker genes from StrainPhlAn69 and functional gene alignment with PanPhlAn70. The reference assembly of Lb. crispatus and Lmb. reuteri on NCBI Refseq were downloaded to generate the respective gene database for PanPhlAn70. Genes on assemblies were called using Prokka71 and annotated against the KEGG gene database using GhostKOALA60.

Viral genome identification and host prediction with spacers

The viral genome assembly and identification followed standard operating procedures72 using VirSorter273 and checkV74, copped with DRAMv75 for manual check. The validated viral contigs (> 2000 bp) were clustered into viral taxonomic operational units (vOTUs) using Cd-dit76, which followed the MIUViG guidelines (>95% sequence identity and > 85% aligned coverage)77. These vOTUs were classified by vConTACT278 to construct gene-sharing networks, visualized through Cytoscape79. The coverage of the vOTUs was calculated to determine the presence in the samples with Minimap280 and the “jgi_summarize_bam_contig_depths” script in the MetaBAT281.

The spacer sequences were mined from vOTUs using two CRISPRs detection tools CRT82 and CRISPRDetect83, and host-virus pairs were validated using SpacePHARER84 to check the spacer presence in the MAGs, where only identical hits were considered as correct matches.

Statistics

All statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.1.2, and the results were visualized using R package ggplot285 unless stated otherwise. The phenotypic data except for NEC incidence (two-sided Fisher’s exact test) was analyzed by linear mixed models with treatment group as a fixed factor and sow as a random factor (lmer function in R package lme486), and Tukey’s post hoc test was used for pairwise comparison (lsmeans function in R package lsmeans87). For microbial diversity comparison, we used Wilcoxon rank-sum test for Shannon index and PERMANOVA (Adonis function in R package vegan88) for beta diversity. Benjamin-Hochberg FDR (false discovery rate) correction was adopted for multiple testing. Distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) was conducted to identify the microbial variation contributed by the FMT and SOW effect using Bray Curtis dissimilarity distance. DESeq2 was adopted to identify differentially enriched microorganisms on the summarized species level and functional KEGG modules, and selected biomarkers were visualized in a heatmap by R package complexheatmap89. The correlation networks of microbial associations with clinical variables were calculated by Pearson’s correlation analysis after centered log-ratio transformation, and the results were visualized by igraph and ggraph (R package).

For the MAG-level analysis, we adopted pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to determine the statistical difference of MAG abundance and replication rate between groups, and the p values were adjusted by Benjamin-Hochberg FDR correction. Fisher’s exact test was applied to identify the differential presence of gene families and KEGG modules and between donor-specific strains and MAGs. Db-RDA was used to show functional dissimilarity of donor-specific MAGs (Bray Curtis distance based on KEGG module presence).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw sequence data of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under Bioproject PRJNA668104.

Code availability

Code for data analysis can be accessed in the public Github repository (https://github.com/yanhui09/FMT-donor).

References

Neu, J. & Walker, W. A. Necrotizing enterocolitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 255–264 (2011).

Alganabi, M., Lee, C., Bindi, E., Li, B. & Pierro, A. Recent advances in understanding necrotizing enterocolitis. F1000Research 8, 107 (2019).

Obladen, M. Necrotizing enterocolitis—150 years of fruitless search for the cause. Neonatology 96, 203–210 (2009).

Coggins, S. A., Wynn, J. L. & Weitkamp, J.-H. Infectious causes of necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin. Perinatol. 42, 133–154 (2015).

Jilling, T. et al. The roles of bacteria and TLR4 in rat and murine models of necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Immunol. 177, 3273–3282 (2006).

Neal, M. D. et al. A critical role for TLR4 induction of autophagy in the regulation of enterocyte migration and the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Immunol. 190, 3541–3551 (2013).

de La Cochetière, M. F. et al. Early intestinal bacterial colonization and necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants: the putative role of Clostridium. Pediatr. Res. 56, 366–370 (2004).

McMurtry, V. E. et al. Bacterial diversity and Clostridia abundance decrease with increasing severity of necrotizing enterocolitis. Microbiome 3, 1–8 (2015).

Pammi, M. et al. Intestinal dysbiosis in preterm infants preceding necrotizing enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microbiome 5, 31 (2017).

Olm, M. R. et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis is preceded by increased gut bacterial replication, Klebsiella, and fimbriae-encoding bacteria. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax5727 (2019).

Bury, R. G. & Tudehope, D. Enteral antibiotics for preventing necrotising enterocolitis in low birthweight or preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2001, CD000405 (2000).

Sharif, S., Meader, N., Oddie, S. J., Rojas-Reyes, M. X. & McGuire, W. Probiotics to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, CD005496 (2020).

Lin, P. W. & Stoll, B. J. Necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet 368, 1271–1283 (2006).

Cui, B. et al. Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) strategy. Gut Microbes 7, 323–328 (2016).

Wilson, B. C., Vatanen, T., Cutfield, W. S. & O’Sullivan, J. M. The super-donor phenomenon in fecal microbiota transplantation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 2 (2019).

Vermeire, S. et al. Donor species richness determines faecal microbiota transplantation success in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 10, 387–394 (2016).

Moayyedi, P. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 149, 102–109.e6 (2015).

Paramsothy, S. et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 389, 1218–1228 (2017).

Mizuno, S. et al. Bifidobacterium-rich fecal donor may be a positive predictor for successful fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 96, 29–38 (2017).

Sangild, P. T. et al. Diet- and colonization-dependent intestinal dysfunction predisposes to necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm pigs. Gastroenterology 130, 1776–1792 (2006).

Brunse, A. et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation route of administration on gut colonization and host response in preterm pigs. ISME J. 13, 720–733 (2019).

Osman, M. et al. Donor efficacy in fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent clostridium difficile: evidence from a 1,999-patient cohort. Open Forum Infectious Dis. 3, 841 (2016).

Kassam, Z., Lee, C. H., Yuan, Y. & Hunt, R. H. Fecal microbiota transplantation for clostridium difficile infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 108, 500–508 (2013).

Paramsothy, S. et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 11, 1180–1199 (2017).

Vrieze, A. et al. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology 143, 913–916.e7 (2012).

Schnabl, K. L., van Aerde, J. E., Thomson, A. B. & Clandinin, M. T. Necrotizing enterocolitis: a multifactorial disease with no cure. World J. Gastroenterol. 14, 2142 (2008).

Sangild, P. T. et al. Invited review: the preterm pig as a model in pediatric gastroenterology. J. Anim. Sci. 91, 4713–4729 (2013).

Penders, J. et al. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. PEDIATRICS 118, 511–521 (2006).

Henderickx, J. G. E., Zwittink, R. D., van Lingen, R. A., Knol, J. & Belzer, C. The preterm gut microbiota: an inconspicuous challenge in nutritional neonatal care. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 85 (2019).

McLaren, M. R. & Callahan, B. J. Pathogen resistance may be the principal evolutionary advantage provided by the microbiome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 375, 20190592 (2020).

Thänert, R., Keen, E. C., Dantas, G., Warner, B. B. & Tarr, P. I. Necrotizing enterocolitis and the microbiome: current status and future directions. J. Infect. Dis. 223, S257–S263 (2021).

Hammer, N. D. & Skaar, E. P. Molecular mechanisms of staphylococcus aureus iron acquisition. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 129–147 (2011).

Parrow, N. L., Fleming, R. E. & Minnick, M. F. Sequestration and scavenging of iron in infection. Infect. Immun. 81, 3503–3514 (2013).

Metges, C. C., Eberhard, M. & Petzke, K. J. Synthesis and absorption of intestinal microbial lysine in humans and non-ruminant animals and impact on human estimated average requirement of dietary lysine. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 9, 37–41 (2006).

Puiman, P. et al. Modulation of the gut microbiota with antibiotic treatment suppresses whole body urea production in neonatal pigs. Am. J. Physiol.—Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 304, G300–G310 (2013).

Smriga, M. & Torii, K. L-Lysine acts like a partial serotonin receptor 4 antagonist and inhibits serotonin-mediated intestinal pathologies and anxiety in rats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 100, 15370–15375 (2003).

Kawai, K., Kamochi, R., Oiki, S., Murata, K. & Hashimoto, W. Probiotics in human gut microbiota can degrade host glycosaminoglycans. Sci. Rep. 8, 10674 (2018).

Martín, R., Martín, C., Escobedo, S., Suárez, J. E. & Quirós, L. M. Surface glycosaminoglycans mediate adherence between HeLa cells and Lactobacillus salivarius Lv72. BMC Microbiol. 13, 210 (2013).

Menozzi, F. D. et al. Enhanced bacterial virulence through exploitation of host glycosaminoglycans. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1379–1386 (2002).

Steimle, A. et al. Weak agonistic LPS restores intestinal immune homeostasis. Mol. Ther. 27, 1974–1991 (2019).

Yoshida, N. et al. Bacteroides vulgatus and bacteroides dorei reduce gut microbial lipopolysaccharide production and inhibit atherosclerosis. Circulation 138, 2486–2498 (2018).

Paramsothy, S. et al. Specific bacteria and metabolites associated with response to fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 156, 1440–1454.e2 (2019).

Ward, D. V. et al. Metagenomic sequencing with strain-level resolution implicates uropathogenic E. coli in necrotizing enterocolitis and mortality in preterm infants. Cell Rep. 14, 2912–2924 (2016).

Brunse, A. et al. Fecal filtrate transplantation protects against necrotizing enterocolitis. ISME J. 1–9 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-01107-5 (2021).

Brunse, A. et al. Enteral broad-spectrum antibiotics antagonize the effect of fecal microbiota transplantation in preterm pigs. Gut Microbes 13, 1–16 (2021).

Østergaard, M. V. et al. Provision of amniotic fluid during parenteral nutrition increases weight gain with limited effects on gut structure, function, immunity, and microbiology in newborn preterm pigs. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 40, 552–566 (2016).

Krych, Ł. et al. Have you tried spermine? A rapid and cost-effective method to eliminate dextran sodium sulfate inhibition of PCR and RT-PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 144, 1–7 (2018).

Ren, S. et al. Gut and immune effects of bioactive milk factors in preterm pigs exposed to prenatal inflammation. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 317, G67–G77 (2019).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584 (2016).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Zheng, J. et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evolut. Microbiol. 70, 2782–2858 (2020).

Tange, O. GNU Parallel: the command-line power tool. The USENIX Magazine (2011).

Uritskiy, G. V., DiRuggiero, J. & Taylor, J. MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 6, 158 (2018).

Menzel, P., Ng, K. L. & Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 7, 11257 (2016).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 27, 824–834 (2017).

Li, D., Liu, C.-M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Zhu, W., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e132–e132 (2010).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. Clustering huge protein sequence sets in linear time. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–8 (2018).

Shen, W., Le, S., Li, Y. & Hu, F. SeqKit: a cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLOS ONE 11, e0163962 (2016).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 726–731 (2016).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. (2013).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Olm, M. R., Brown, C. T., Brooks, B. & Banfield, J. F. dRep: a tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 11, 2864–2868 (2017).

Pasolli, E. et al. Extensive unexplored human microbiome diversity revealed by over 150,000 genomes from metagenomes spanning age, geography, and lifestyle. Cell 176, 649–662.e20 (2019).

Nissen, J. N. et al. Improved metagenome binning and assembly using deep variational autoencoders. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 555–560 (2021).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform. 11, 119 (2010).

Stewart, R. D., Auffret, M. D., Snelling, T. J., Roehe, R. & Watson, M. MAGpy: a reproducible pipeline for the downstream analysis of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). Bioinformatics 35, 2150–2152 (2019).

Brown, C. T., Olm, M. R., Thomas, B. C. & Banfield, J. F. Measurement of bacterial replication rates in microbial communities. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 1256–1263 (2016).

Truong, D. T., Tett, A., Pasolli, E., Huttenhower, C. & Segata, N. Microbial strain-level population structure and genetic diversity from metagenomes. Genome Res. 27, 626–638 (2017).

Scholz, M. et al. Strain-level microbial epidemiology and population genomics from shotgun metagenomics. Nat. Methods 13, 435–438 (2016).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Guo, J., Vik, D., Pratama, A. A., Roux, S. & Sullivan, M. Viral sequence identification SOP with VirSorter2. protocols.io https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bwm5pc86 (2021).

Guo, J. et al. VirSorter2: a multi-classifier, expert-guided approach to detect diverse DNA and RNA viruses. Microbiome 9, 37 (2021).

Nayfach, S. et al. CheckV assesses the quality and completeness of metagenome-assembled viral genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 578–585 (2021).

Shaffer, M. et al. DRAM for distilling microbial metabolism to automate the curation of microbiome function. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 8883–8900 (2020).

Li, W. & Godzik, A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22, 1658–1659 (2006).

Roux, S. et al. Minimum Information about an Uncultivated Virus Genome (MIUViG). Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 29–37 (2019).

Bin Jang, H. et al. Taxonomic assignment of uncultivated prokaryotic virus genomes is enabled by gene-sharing networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 632–639 (2019).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498 (2003).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Kang, D. D. et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 7, e7359 (2019).

Bland, C. et al. CRISPR Recognition Tool (CRT): a tool for automatic detection of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats. BMC Bioinform. 8, 1–8 (2007).

Biswas, A., Staals, R. H. J., Morales, S. E., Fineran, P. C. & Brown, C. M. CRISPRDetect: a flexible algorithm to define CRISPR arrays. BMC Genomics 17, 356 (2016).

Zhang, R. et al. SpacePHARER: sensitive identification of phages from CRISPR spacers in prokaryotic hosts. Bioinformatics 37, 3364–3366 (2021).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis Using the Grammar of Graphics (Springer, 2016).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Statistical Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Lenth, R. V. Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. J. Statistical Softw. 69, 1–33 (2016).

Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Vegetation Sci. 14, 927–930 (2003).

Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by the Independent Research Fund Denmark under project No. 8022-00188B, and Y.H. was supported by the China Scholarship Council under a PhD scholarship (No. 201706350028). We want to acknowledge all laboratory technicians and animal caretakers for their support in this study. We thank Professor Per Torp Sangild for his helpful suggestions. We also acknowledge the high-performance computing platform provided by Danish National Supercomputer for Life Sciences (Computerome, https://computerome.dtu.dk).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.B., T.T., and D.S.N.; Investigations: Y.H., A.B., and L.D.; Methodology: A.B., Y.H., L.D., W.P.K., and G.V.; Project administration: A.B., T.T., and D.S.N.; Resources: A.B., T.T., W.P.K., D.S.N.; Supervision: T.T., G.V., and D.S.N.; Software: Y.H. and G.V.; Formal analysis: Y.H. and A.B.; Data curation: Y.H. and A.B.; Visualization: Y.H. and A.B.; Writing-original draft: Y.H. and A.B.; Writing-review and editing: all authors. Funding acquisitions: A.B., T.T., and D.S.N. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hui, Y., Vestergaard, G., Deng, L. et al. Donor-dependent fecal microbiota transplantation efficacy against necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm pigs. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 8, 48 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-022-00310-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-022-00310-2

This article is cited by

-

Necrotizing enterocolitis: recent advances in treatment with translational potential

Pediatric Surgery International (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.