Abstract

Prior to the availability of whole-genome sequences, our understanding of the structural and functional aspects of Prunus tree genomes was limited mostly to molecular genetic mapping of important traits and development of EST resources. With public release of the peach genome and others that followed, significant advances in our knowledge of Prunus genomes and the genetic underpinnings of important traits ensued. In this review, we highlight key achievements in Prunus genetics and breeding driven by the availability of these whole-genome sequences. Within the structural and evolutionary contexts, we summarize: (1) the current status of Prunus whole-genome sequences; (2) preliminary and ongoing work on the sequence structure and diversity of the genomes; (3) the analyses of Prunus genome evolution driven by natural and man-made selection; and (4) provide insight into haploblocking genomes as a means to define genome-scale patterns of evolution that can be leveraged for trait selection in pedigree-based Prunus tree breeding programs worldwide. Functionally, we summarize recent and ongoing work that leverages whole-genome sequences to identify and characterize genes controlling 22 agronomically important Prunus traits. These include phenology, fruit quality, allergens, disease resistance, tree architecture, and self-incompatibility. Translationally, we explore the application of sequence-based marker-assisted breeding technologies and other sequence-guided biotechnological approaches for Prunus crop improvement. Finally, we present the current status of publically available Prunus genomics and genetics data housed mainly in the Genome Database for Rosaceae (GDR) and its updated functionalities for future bioinformatics-based Prunus genetics and genomics inquiry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stone fruit (peaches, cherries, apricots, plums) and almond belong to the Prunus genus, which encompasses approximately 250 species1 that share a small (250–300 Mbp) and highly syntenic genome2,3 with eight basic chromosomes. Most of the cultivated species are diploid with two exceptions, the hexaploid European plum (P. domestica) and the tetraploid tart cherry (P. cerasus). Sexual compatibility is frequent, particularly within members of the same subgenus: Amygdalus (peach-almond), Prunus (apricot-plum), and Cerasus (cherries), although certain crosses between species belonging to Amygdalus and Prunus subgenera are also possible.

The deployment of basic molecular technology during the past half century advanced our understanding of important aspects of Prunus genetics, including the consolidation of its phylogenetic relationships, the analysis of its genetic variability, the development of genetic markers and the construction and comparison of linkage maps, the integration of a large number of major genes and quantitative trait loci (QTLs) in these maps, and the identification of markers tightly linked to some traits enabling their selection in plant breeding4. Plausible hypotheses about candidate genes for certain characters were established, such as the genes responsible for the melting vs. nonmelting fruit flesh consistency (M/m) and freestone vs. clingstone flesh adherence to the stone (F/f)5,6, the gene for evergrowing (Evg/evg) for which the recessive homozygote is associated with continuous leaf growth and a failure to enter dormancy7, and the two genes involved in the self-incompatibility system8 (Table 1). However, positional cloning of trait-controlling genes was hampered by long intergeneration times, time and space constraints on progeny numbers in mapping crosses, marker availability in specific chromosomal regions, and finally by the lack of efficient transformation methods in most species other than hexaploid plum9.

The public availability of a peach high-quality DNA sequence in 201010 and later those of other Prunus species11,12,13 unlocked the Prunus genome, paving the way to build new knowledge for basic and applied purposes. Our objective in this paper is to review the major achievements that have taken place in the genetics of peach and other Prunus crops as a consequence of the availability of whole-genome sequences (WGSs), emphasizing the new genes discovered, and in future targets that will allow us to reach a much deeper understanding of the genetics of a group of species that are important sources of high-quality and healthy nutrients and serve as models for tree species.

The peach genome sequence and other Prunus genomes

The plan to sequence the peach genome emerged in the middle of the past decade. Peach was an excellent candidate for shotgun sequencing having a small genome estimated at 265 Mb14 and extended genomic and genetic resources, such as linkage maps, EST collections, and BAC libraries4. The decision to sequence the peach genome was announced by the Joint Genome Institute in 2007 and soon after an Italian consortium (DRUPOMICS) joined the US efforts to form the International Peach Genome Initiative (IPGI) that included scientific institutions from Chile, Spain, and France as well.

The use of whole-genome shotgun sequencing with Sanger chemistry and a completely homozygous genotype, the “Lovell” double haploid PLov2-2n, were crucial for the success of the initiative. Sequencing concluded in late 2009 with the deposition of 3,729,679 paired-end Sanger sequences corresponding to 8.47× genome coverage. Assembly and annotation of genes and repeated sequences were finished in early 2010 and the peach genome sequence was released, under a Fort Lauderdale agreement on April 1, 2010, being the first freely available Rosaceae genome. The assembly10 was arranged in 2720 contigs and 234 scaffolds covering 227.3 Mb. Scaffolds were assigned to chromosomes using an improved version of the Prunus reference map2,15 to form a chromosome-scale assembly with 218.3 Mb (96%) of sequences in 8 pseudomolecules and 194 unmapped scaffolds (Table 2), providing a sequence accuracy of 99.96% and a completeness of 99%. A combination of de novo identification and structural tools together with similarity searches was used for the annotation of the 84.4 Mb (37.14%) of repetitive sequences. Several homology-based predictors, incorporating transcript assemblies from Rosaceae and Prunus ESTs and protein homology with the major sequenced plants, were used to derive 27,852 protein-coding genes and 28,689 protein-coding transcripts. Comparative analyses with other sequenced species and the detection of duplicates within the genome itself highlighted that peach has not undergone recent whole-genome duplication after the ϒ Eudicot hexaploidization10.

Further analyses of the peach WGS suggested several areas for improvement, including unmapped and randomly oriented scaffolds; correction of putative misassemblies; and better base accuracy, contiguity, and gene prediction. These goals were achieved in the second version of the peach genome (Peach v2.0)16 using a combination of high-density linkage maps (4 maps and 3576 markers) and high-throughput DNA and RNA sequencing. The improved chromosome-scale assembly is now 58 scaffolds spanning 225.7 Mb (99.2%) arranged in 8 pseudomolecules, 52 of which are oriented (223.3 Mb; 98.2%). Sixty-four-fold Illumina whole-genome sequencing of the reference genotype was used to correct 859 false single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 1347 indels. Moreover, the assembled next-generation sequencing (NGS) contigs enabled the closing of 212 gaps with a 19.2% improvement in the contig L50. Gene annotation was improved using a large amount of RNA-seq data from various peach tissues and organs, as well as annotated repeats that include low copy repeats and a complete set of Helitron transposons (Table 2).

Two other Prunus WGSs (Table 2) were obtained using high-throughput NGS Illumina sequencing: (1) Japanese apricot (P. mume)11, producing a fragmented assembly of 237 Mb with 31,390 protein-coding genes and 45% (106.8 Mb) of repeated sequences; and (2) cherry (P. avium)12 with a total length of 272.4Mb, containing 43,349 protein-coding genes and 119.4 Mb (43.8%) of repetitive sequences. Third-generation sequencing methods based on single-molecule sequencing (such as Pacific Biosciences, Oxford Nanopore, and Moleculo) capable of obtaining long reads, up to 50 kb, coupled with short read NGS technologies have provided new inputs to genome sequences. Recently, using a combination of ultra-high coverage (1265.6-fold sequences) Illumina and PacBio long read methodologies, the wild cherry P. yedoensis genome was sequenced13, producing an assembly of 323.8 Mb with 41,294 protein-coding genes (Table 2). The sequence of “Texas” almond (P. Arús, unpublished results) is already publicly available at the Genome Database for Rosaceae (GDR).

Other de novo assemblies of Prunus genomes are underway, such as that of another sweet cherry cultivar, “Regina” (E. Dirlewanger, unpublished results), while those for other Prunus crops, plum, apricot, and other wild crop relatives are expected to be released in the next several years. These new sequences provide an opportunity to unravel genetic diversity—still present in Prunus wild species—that had been lost in these crops during thousands of years of selection and breeding. This genomic information could be exploited by introgressing new desirable alleles into the cultivated species via classical or marker-assisted breeding (MAB) methods. It could also be the starting point for applying gene editing and cisgenesis to Prunus crops in the efforts to create new targeted variability in genes controlling relevant agronomic traits, such as biotic and abiotic stress resistance, for which the cultivated species, peach in particular, are notably lacking.

Soon after the release of the peach genome sequence, the International Peach SNP consortium developed the first peach 9K SNP array v117. Furthermore, the extensive Prunus synteny2 made the peach genome a valuable reference to identify SNPs in related crops10,18 enabling the construction of a cherry 6K SNP array19. Recently the peach and cherry arrays have been updated with 9000 additional SNPs covering previous gaps (I. Verde, unpublished results). In addition to SNP arrays, resequencing data from sets of individuals has enabled unprecedented in-depth analyses of variability and linkage disequilibrium (LD)-based analysis that resulted in the first genome-wide association studies (GWASs). Such applications of the Prunus WGSs are reviewed below.

Whole-genome analysis of Prunus diversity

Prunus variability, domestication, and crop evolution

The most comprehensive P. persica diversity analysis was performed with the 9K peach SNP array17 and a collection of 1580 accessions (including peaches and few closely related Prunus species)20. SNP data identified some unknown somatic mutants and confirmed others that were already reported. In agreement with the known breeding history of peach and previous results with simple sequence repeats (SSRs)21,22, the unique accessions showed a relatively high kinship coefficient corresponding to an average relationship of grandparent–grandchild or half-sibs and were divided into three main subpopulations: two based on geographic distribution (oriental and occidental accessions) and the third, a separation within occidental materials as traditional landraces or those derived from breeding programs. The cherry 6K SNP array19 was used to characterize 210 cherry accessions. As for peach, variability in sweet cherry was differentially distributed between cultivars and landraces and, in the latter, among geographic locations23.

Whole-genome resequencing of germplasm collections has also been used for variability analysis, particularly in peach, including cultivars with variability underrepresented in the cultivar panel used for the development of the 9K SNP array (such as those from Asian germplasm collections) and Prunus wild species. In addition, such high level of genome definition has provided relevant knowledge on domestication and crop evolution processes. Most Prunus cultivated species originated in central Asia, although their recent evolution seems to have followed substantially different patterns. For example, peach and almond, two of the genetically closest relatives, seem to have arisen from a common ancestor in central Asia by the time of the uplift of the Central Asian Massif around 8 MYA24,25, and then followed completely different paths, almond in the dry environments of the central and western Asian steppes and peach in the humid, subtropical climate of south-western China24. Important trait differences accumulated such as dry vs. fleshy fruit and outcrossing vs. selfing, with many derived biological and populational consequences25. Recent comparison of genome-wide diversity patterns in almond and peach has identified regions with signatures of selection that occurred during domestication that interestingly often overlap in both species despite having occurred independently in each around 5000 years ago26. Likewise, during P. persica domestication, which probably took place through a single domestication event from wild peaches27, some genes were subjected to artificial selection as deduced from comparisons of the regions showing selective sweeps among domesticated peaches (including landraces, edible and ornamental cultivars) and their wild relatives27,28,29. Such regions contain genes that may have contributed to peach domestication and cultivar differentiation and warrant further research. Although interspecific hybridization events, such as those accompanying creation of some Prunus crops like Japanese plum30, might be associated with increased mutation rates, low evolutionarily rates reported for perennial plants, peach in particular31, may explain the close relationships among Prunus species.

Although SSRs and SNPs are and will remain the principal genotyping tools in Prunus species lacking a reference genome, the continuous cost reduction of sequencing techniques forecasts the routine use of resequencing data in future Prunus variability studies. Currently, increased sequencing efforts are feeding the databases and providing important sequence resources for diversity and domestication analyses. In a near future, we may expect an increasing number of studies focused on the identification of particular genomic regions, such as those showing differential patterns of diversity as a consequence of domestication or breeding, gene families, or DNA features such as transposable elements (TEs). Such studies may answer fundamental questions concerning when, where, and how domestication events took place in the development of certain Prunus species. However, although promising, relying on available sequence data has a major drawback since most has been done with resequencing techniques that yield short reads and with low depth. Their alignment against the “Lovell” reference genome may fail to map genetic regions that have been lost or duplicated during the domestication process. The recent development of new long-range sequencing technologies should resolve this problem.

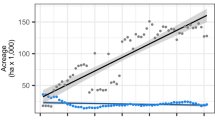

Whole-genome diversity has been exploited in GWAS using both SNPs and whole-genome resequencing data with a minor or major depth coverage. Understanding the extension and decay of LD in the species of interest, and in particular in the panel of genotypes used for association analysis, is essential when considering GWAS. WGS data has identified fast LD decay in apricot, spanning <100 bp18. Similarly, LD decays fast in ornamental P. mume accessions (r2 ≤ 0.2 at 50 kb to few hundreds of base-pairs depending on the population)32 and a little more moderately in cherry (r2 ≤ 0.2 at 100 kb)23. In contrast, large LD extensions were observed in peach (r2 ≤ 0.2 between 0.8 and 1.4 Mb depending on the population20). These findings have practical implications: while a large number of SNPs will be required to find some associated with the allele of interest in apricot, lower SNP density should be sufficient in peach. However, as a trade-off, associated SNPs in the former will be most likely closer to the gene than in peach. As a proof of concept, GWAS for several qualitative traits was performed in peach20, identifying haplotypes linked to the loci or genes already known to be responsible for the trait. GWAS using resequence data from 129 peach accessions28 identified association signals at various loci for a set of 12 agronomic characters and proposed candidate genes for two of them. Recently, the stony hard flesh (Sh) locus was mapped in a panel of peach genotypes using the 9K SNP array33. A highly associated SNP was found that, due to the extended LD of peach at this chromosomal region consequence of its location close to the centromere, was organized in a haplotype about 1.9-Mb long. In this case, higher SNP density would not have translated to higher precision.

Up to now, GWAS has mainly been performed for agronomic and fruit traits evaluated in a single location, usually with small-scale phenotyping techniques. In the near future, we may expect to see GWAS of genetic traits related to crop adaptation, probably involved in epigenetic variability and genome instability, as already evident in some large-scale Arabidopsis studies34,35. In addition, thanks to the current inclusion of new technologies in the life sciences field, we may expect that new high-throughput phenotyping methods such as those based on three-dimensional imaging36,37 or large-size plant mobile screening platforms38 will soon provide enormous amounts of data as substrate for future GWAS.

Disadvantages of the multi-year intergenerational period of Prunus species, the seasonality of crop production, and large plant sizes are balanced by the ability to clonally propagate and maintain heterozygous genotypes for many years. This enables evaluation of the same genotype under different climatic and management conditions. Future GWAS strategies should consider the analysis of existing genotype collections replicated in different locations to incorporate environmental effects in the analysis.

Haploblocking Prunus genomes

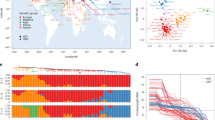

The use of high-density SNP and resequencing data allows high-resolution genome analysis such as “haploblocking”, or haplotype blocking, a means of dividing the genome of Prunus crop individuals into informative genetic segments. Each segment (called a haploblock) has variants (called haplotypes) within and across individuals. Alleles of the loci within each haplotype tend to be co-inherited owing to their close linkage. Functional utility can be assigned to haplotypes, such as trait effects and ancestral origin. The managers of haploblocked genomes are geneticists and breeders, and so the patterns of co-inheritance described by haploblocking are designed to capture features of value to such users (Fig. 1). Haploblocking provides a fascinating overview of the genetics of any individual examined.

Haplotypes are the variants of haploblocks—sets of co-inherited alleles. To each haplotype can be assigned trait influences, ancestry, and other genetic features. If a breeding parent does not have coupling-phase linkage for desirable alleles within a haploblock containing multiple quantitative trait loci, such tight linkage might be targeted for recombination in the next generation

At the broadest level, whole chromosomes are haploblocks, described by their genetic length in centiMorgans (cM), but a finer level of compartmentalization is possible and desirable. In practice, haploblocking divides up chromosomes, establishing systematic criteria for helpfully delimiting each haplotyped region. The series of haploblocks along each chromosome act as an easily manageable number of linked multi-allelic loci, carrying all the information of the underlying genotypic data39. A requirement for haploblocking is phased, high-resolution genotypic data, which is currently obtained by genotyping individuals with high-density SNP assays and correct phasing for each individual that is achieved, for example, via inheritance analyses using the software FlexQTL™40.

There are several ways that Prunus crop haploblocks have been or are being delimited. The pedigree-based approach identifies positions of historical recombination in the pedigreed germplasm and uses these positions to delimit haploblocks. In U.S. breeding germplasm of sweet cherry41 and peach (C. Da Silva Linge, pers. comm.), recombination positions used to define haploblock boundaries were all of those detected in the known progenitor generations leading to cultivars of the germplasm set. Recombination events were positioned with VisualFlexQTL40, and finally haplotypes were assigned to each haploblock using PediHaplotyper39. As germplasm managers using pedigree-based haploblock information examine haplotypes through ancestral generations, they do not have to track complicating recombinations within haplotypes—there is 100% LD within haploblocks. Note that this coupling-phase linkage within a haploblock can be broken into subsequent generations, with a probability determined by the genetic distance between loci. Other ways to establish haploblocks include using regular, arbitrary lengths for each haploblock, such as 1 or 5 cM; the diversity-based approach, whereby the observed degree of LD along each chromosome at increasing levels of genetic diversity among sets of individuals, from families to across species and even across genera, are used to define segments that have rarely recombined (A. Lawton Rauh, pers. comm.); and the aggregate-marker approach, which combines into haploblocks sets of markers positioned within very short physical distances, enabled by purposeful SNP clustering around focal points as done for design of the 20K apple SNP array42 and the upcoming 9 + 9K peach and 6 + 9K cherry SNP arrays. WGSs are a critical foundation of haploblocking, as they determine the genomic positioning of SNP markers to ensure that each chromosome is covered with genetic polymorphism data. Although haploblocks are described in cM, physical anchoring to the WGS ensures ready connection to associated DNA sequences, sequence motifs, and annotated genes. Research community consensus on the positions and labels of a standardized set of haploblocks for each crop should provide a framework for comparative genetics that is easier to use than a reference genetic map of common markers. A proposed basis for such a haploblock framework is the pedigree-based haploblocks derived from the set of 50–100 ancestors that are common to most cultivars of a crop.

Haplotypic variation across haploblocks is powerful genetics information. Haplotypes are genotypically distinguished by differences in their set of alleles (ultimately DNA sequence variation), such as ABBAABB vs. ABABBBB vs. BBBBBBB. These haplotypes can also be functionally distinguished. Where major genes or QTLs for traits of interest lie within (or span) a haploblock, the associated effects of each haplotype on such traits can be calculated and the information attached. Each haplotype can also be traced through the pedigree from the earliest known ancestor that contributed the haplotype through to all descendants carrying that identical-by-descent haplotype. Visualizing the “haplotype mosaics” of this shared ancestry43 can provide a valuable experience of elite genomes (section “Applications of genome information in Prunus improvement: MAB, MAI, genomic selection, and visualization of the genome-wide genetics of elite individuals”). Identity-by-state among germplasm of one or more haplotypes extending over large genetic distances can be used to infer recent shared common ancestry. Other features relevant to breeding and biodiversity management can also be assigned, such as haplotypes that are overrepresented or under-represented in offspring that thereby contribute to segregation distortions, excessive heterozygosity, and excessive homozygosity. Examining the ancestral origins and germplasm distribution of trait locus alleles or segregation-distorting alleles is a relatively simple task using haploblocks.

Haploblocking is a newly available approach to make sense of the vast quantity of genome-wide genotypic data that can now be readily obtained on germplasm individuals. Critically, it involves the consideration of each individual in genetic comparisons, examining the haplotypes that each carries, rather than simply using scaled-up quantitative analyses. New software in data curation and graphical genotyping is needed to facilitate a multitude of practical applications that beckon in breeding and biodiversity management.

Genetics of agronomic characters

During the recent decades, many efforts have been directed to identify loci and the underlying genes that explain the phenotypic variability of a number of agronomic traits. Thanks to the availability of reference genomes, once the chromosomal position for a major gene or QTL is established, it is possible to easily discover and develop additional markers that enable reducing the size of the target region, where a small set of genes can be identified. This approach, supported by many RNA-seq datasets available for most Prunus species10 and epigenetic analysis, has led to the discovery of several causal genes for certain traits and of strong candidates for others in peach and other Prunus (Table 1) that are reviewed below.

Phenology (blooming and maturity dates) and climate change adaptation

In Prunus species, as for woody perennial plants in temperate and boreal zones, survival and production depend on precise timing of growth and rest periods in synchrony with seasonal changes in temperature44. Flower bud differentiation takes place at the end of the summer and buds continue their development until mid-autumn, when they enter into the dormant stage45. The first step of dormancy is growth cessation and meristem acclimatization to cold. Dormancy can be separated into two main phases: (1) endodormancy, when meristems are unable to initiate growth under favorable conditions, followed by (2) ecodormancy, when meristems can resume growth if temperatures are optimal46. During endodormancy, a certain amount of cold temperatures, defined as chilling requirement (CR), must accumulate prior to the bud being released from endodormancy. Subsequently, the bud will respond to heat, leading to flowering when heat requirements (HR) are satisfied46. Consequently, flowering date is determined by CR and HR, and fruit/nut maturity timing will be associated with flowering date and to the length of the fruit development period.

In the context of global climate change, flowering phenology of deciduous tree species is crucial as it may affect commercial productivity. In fruit tree orchards, flowering phenology has an indirect influence on spring frost damage, pollination, maturity, and fruit production. Climate warming delays the endodormancy release while it accelerates bud growth. Therefore, depending on the balance between these two antagonistic effects, budbreak can be either advanced or delayed and can even be compromised owing to insufficient cold temperature during winter. Additionally, warm temperatures in spring and summer are responsible for an advance of the maturity date. Consequently, it is crucial to anticipate the impact of climate warming on phenological processes with the aim to establish prospective strategies to create new cultivars that are well adapted to future climate. Hence, numerous studies are aimed at deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of bud dormancy and flowering and maturity dates.

Many Prunus major genes and QTLs have been described for phenology-related traits such as CR, HR, and flowering and maturity dates. For bloom date, major QTLs were detected on linkage group 6 (G6) for peach and on G4 for apricot and sweet cherry, whereas for maturity date, a major QTL was detected on G4 for all three crops47. Fine mapping of the major locus controlling the maturity date in peach identified a precise QTL interval of 220 kb and enabled the identification of a NAC transcription factor as the candidate gene48 (Table 1) confirming results previously described47. With a multi-progeny mapping strategy, 18 peach progenies in total, additional QTLs were detected for flowering date (G4, G6), maturity date (G2, G4, G6), and for fruit development period (G4, G6)49. In sweet cherry, one stable QTL for CR and bloom date was detected in the same region on G450. Candidate genes underlying this QTL were investigated using the peach genome sequence and key genes were identified for these two traits51. Most of the genes were those involved in chromatin remodeling (ARP4, EMF2, PIE1) and in gibberellin homeostasis (KS and GA2ox). Thanks to the high synteny existing among Prunus species2, it was possible to use the peach and the sweet cherry genomes to compare homologous regions such as the QTL on G4 controlling CR in peach, sweet cherry, and Japanese apricot52.

Expression of the dormancy-associated MADS-box (DAM) genes has been extensively analyzed and their key role in the endodormancy establishment and maintenance was demonstrated. DAM5 and DAM6 genes are upregulated during growth cessation and downregulated by cold exposure during winter in peach53, Chinese cherry54, sweet cherry55, and Japanese apricot52,56,57. In peach, histone modifications of DAM gene expression were reported58. In sweet cherry, DNA methylations and small interfering RNAs involved in the silencing of PavMADS1 during cold accumulation and dormancy release were analyzed59, and research on the epigenetic regulation of the DAMs, through chromatin immunoprecipitated-sequencing (ChIP-seq) analyses, is in progress55.

New methods that resolve phase-switches and reconstruct contig-length phase blocks60 make it possible to identify the haplotypes for each individual, which are especially useful for highly heterozygous genotypes. This ability is important for phenological traits, which are often complex, highly polymorphic, and may involve epigenetic regulation. Genomic selection can be a useful breeding strategy for the phenological traits and promising results were obtained for apricot61 and sweet cherry62 for flowering and maturity dates. In addition to these tools, spontaneous mutants are highly valued for identifying genes responsible for phenotypic variation. Many spontaneous (epi-)mutations were found in Prunus species63 and several of them were associated with flowering date. In sweet cherry, the very early-flowering cultivar “Cristobalina” was issued from a spontaneous mutation of “Temprana de Sot”64. In apricot, early-flowering “Rojo Pasión Precoz” was derived from the recently released “Rojo Pasión” apricot cultivar65. To date, no clues about the determinism of these extreme phenotypes are available. Using reference WGSs and resequencing data of these mutants or of cultivars with contrasting phenotypes, it should be possible to identify the causal genes.

Fruit-related characters

Fruit size, shape, and color

Fruit appearance highly influences consumer’s choice. Therefore, large fruits, with a certain fruit color and shape are breeder’s priorities. Fruit size is one of the most important phenotypic traits that distinguishes modern Prunus cultivars from their small-fruited wild ancestors. For example, in sweet cherry, wild (syn. mazzard), landrace, and modern bred cultivars typically have fruit sizes of ~2, 6, and 12 g, respectively66. Discovering major loci underlying genes that determine fruit size has been a high priority due to the importance of fruit size to growers’ profitability and the need for breeders to select against small-fruited alleles when introgressing traits from wild Prunus species.

Fruit size is a classic quantitative trait controlled by many loci, highly influenced by the environment, with >50 QTLs identified to date. Many fruit size studies have involved crossing large-fruited modern cultivars with Prunus wild relatives, which in peach consisted of crosses with P. davidiana, an ornamental small-fruited P. persica and almond P. dulcis49,67,68,69. A comparison of the nucleotide diversity in genome sequences of these wild species (P. kansuensis and P. davidiana) with that of cultivated peach identified regions associated with selective sweeps related to domestication and breeding10. In sweet cherry, a fruit size QTL region on chromosome 2 was shown to be under positive selection41. In certain cases, QTLs co-locate across species such as the G7 QTL discovered in both peach68 and Japanese plum70. In other cases, the co-location of fruit size genes with fruit firmness, such as the QTL on G5 in cherry71, raises the question of whether this is a pleiotropic locus. However, it will take the discovery of the underlying genes to know whether there are one or more genes responsible for these QTLs.

To date, members of two gene families have been associated with the fruit size increase that accompanied domestication. The first study involved the FW2.2 cell number regulator (CNR) gene family originally identified in tomato72. A total of 23 FW2.2/CNR family members were identified in the peach genome, two of these CNRs co-located with fruit size QTLs on G2 and G6 in a domesticated sweet cherry × mazzard cross73 (Table 1). The gene family member on G2, named PavCNR12, was hypothesized to contribute to an increase in fruit size by increasing mesocarp cell number. The gene family member on G6, PpCNR20, is also a candidate gene for a fruit weight QTL identified in peach74. Another gene implicated in the control of fruit size in sweet cherry is a member of the Cytochrome P450 (CYP) subfamily, termed CYP78A that has been shown to be involved in plant organ growth and development including tomato fruit75. The transcript level for PaCYP78A9 was significantly higher in a cherry landrace compared to a mazzard cherry76. In addition, silencing of PaCYP78A9 during sweet cherry fruit development caused a reduction in fruit size due to a reduction in both mesocarp cell number and size. To date, this gene has not been shown to be associated with a fruit size QTL.

Prunus fruits show large intraspecific variability for fruit and stone shape, which can be used for germplasm characterization. Similar to fruit size, cell number may determine fruit shape. This is the case of the flat shape of peach fruits, which is primarily determined by the regulation of cell production in the vertical direction during early fruit development77. The flat shape locus S/s has been mapped on G6, where S is a partly dominant allele; ss genotypes produce round fruits, Ss genotypes produce flat fruits and fruits from SS trees abort a few weeks after fruit set78. The participation of a second gene producing fruit abortion has been hypothesized, although pistils of SS flowers show already a differential phenotype compared to Ss and ss types (Fig. 2). Association analysis of SNPs and indels in the S locus suggests the gene Prupe.6G281100, a leucine-rich receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK), as a candidate for the fruit shape (Table 1). The best protein hit of this gene occurred with AtRLP12, which in Arabidopsis functionally complements CLAVATA2, a key regulator that controls the stem cell population size79. The flat-associated allele of Prupe.6G281100 is not expressed, resembling a dosage mechanism. However, polymorphisms in this gene do not completely explain the trait in all germplasm, suggesting the participation of additional alleles or genes77,79. Apart from the peach flat shape, investigation of genes determining diverse shapes (i.e., oblate or elliptic) is still lacking.

a Manhattan plot from Micheletti et al.23 data. Chromosomes are marked with different colors on the horizontal axis. The horizontal green line represents the significance threshold for the association. b Images of flowers, pistils, and fruits of a round (left) and a flat (right) fruit cultivar where it can be seen that the flat vs. round character is determined early in flower formation

The inheritance of white vs. yellow flesh in peach, one of the first Mendelian traits described in Prunus (Y/y), maps to G180 with white flesh dominant over yellow flesh. The pigments abundant in the yellow peaches are carotenoids, for which the biosynthetic pathway is well known. Subsequently, the gene underlying the Y locus was shown to be a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 (PpCCD4) that is considered responsible for carotenoid degradation in white-fleshed peaches81. The dominant functional allele was found to confer white flesh while yellow peaches have loss-of-function mutations of this gene82 (Table 1).

Anthocyanin pigments in Prunus are responsible for the red fruit skin and flesh color including the red “blush” on peach fruit. Their biosynthetic pathway is well studied in many crops including apple where a R2R3 MYB anthocyanin transcription factor, MdMYB10, controls red fruit flesh color83,84. Likewise, in Prunus, there is strong evidence that this same anthocyanin transcription factor, MYB10, on G3 is the major gene responsible for the red color differences (Table 1). In sweet cherry, mahogany fruit (skin and flesh) color is dominant to yellow fruit color and the major QTL on G3 maps to an interval containing PavMYB1085. This same G3 interval was shown to have major genes/QTLs controlling anther color in almond × peach progenies69, red blush on the skin in peach86,87, and skin color in Japanese plum70. However, other QTLs controlling the percentage of red skin color in peach were identified on G4, G5, and G649. Some of these QTLs have been shown to exhibit epistatic interactions85, and this has been extended to interactions among the involved genes. For example, the red-flesh peach type, called “blood type,” was found to be controlled by multiple loci with a candidate gene identified on chromosome 5 that regulates the transcription of PpMYB1088 (Table 1).

Owing to an excellent understanding of pigment biosynthesis pathways and the high heritability for color, the molecular characterization of fruit color is the most advanced. Yet, knowledge on the molecular basis of the more subtle differences in color will require the identification of the full set of genes and an exploration of epistatic interactions. For example, a transcriptomic analysis of fruit ripening in plum revealed the co-expression of the MYB transcription factor with another important anthocyanin transcription factor, a basic helix-loop-helix, bHLH89.

The second trait for which the identification of likely candidate genes is most advanced is mesocarp cell number where the comparisons were made among representatives of wild and domesticated germplasm. Characterizing the alleles for candidate genes is an important next step made possible by the increasing amount of sequence data from a broader range of plant materials. This enables proof-of-function experiments such as those described for the sweet cherry fruit size gene PaCYP78A976. These types of experiments are also critical for addressing hypotheses of pleiotropy that have been suggested for a few co-locating QTLs. In addition to narrowing QTL regions to reduce the number of candidate genes, fine mapping studies are needed to dissect the trait-rich QTL regions. Obvious first targets are the trait-rich clusters on chromosome 2 in sweet cherry41 and chromosome 4 in multiple Prunus species70,90,91 (A. Iezzoni, unpublished results).

Fruit flavor and flesh consistency

Apart from the external appearance, sensorial attributes (like flavor and flesh consistency) are highly relevant for fruit quality. Prunus fruit flavor is dependent on the concentrations and balance of sugars and acids. Elucidating the genetic control of these metabolites is difficult due to the metabolic complexity, changes in individual sugar and acid levels during fruit maturation, and the environment. Numerous QTLs have been identified on all eight Prunus chromosomes for traits and metabolites associated with sweetness (e.g., soluble solid content (SSC), individual sugars: fructose, glucose, sucrose and sorbitol), and acidity (e.g., pH, titratable acidity, and malic acid). In peach, one QTL mapped to the top of G5 behaves as a major locus, D/d, determining low acid (subacid) content92,93,94. In general, fruit can be placed into two groups, normal acid and low acid, with low acidity determined by the dominant allele. The physical map location of the D locus has been narrowed to a 100-kb region93 and a candidate gene coding for an auxin afflux carrier family protein (ppa006339m; Prupe.5G004300) was proposed based on GWAS28 (Table 1). For the components of sweetness, many QTLs have been identified most with minor effects. For example, six QTLs for SSC were found in a collection of 18 populations of peach49, and numerous QTLs for sugar metabolism during peach fruit development along with co-localized candidate genes have been reported95. Yet, the determination of the underlying genes and their metabolic functions is in its infancy. Global mRNA and protein profiling results can provide support for candidate genes and identify key metabolic switches and co-expression gene networks96 controlling the metabolism and accumulation of compounds contributing to fruit flavor. This approach may be particularly useful for sweetness, as the vast majority of the QTLs identified have minor effects. It was successfully used to characterize differences in sugar metabolism pathways between two Japanese plum cultivars, the climacteric “Santa Rosa” and its non-climacteric bud sport mutant97, resulting in the identification of several highly connected sugar metabolism-associated genes that could be acting as metabolic hubs. These highly connected genes could be targets for future study.

Fruit flesh texture is one of the key traits in most peach breeding programs. On one side, it determines two different fruit typologies: melting flesh (MF) for fresh consumption, and non-melting (NMF), mainly for canning. On the other side, flesh texture also determines postharvest behavior, with other fruit texture types as slow melting (SMF) and stony hard (SH), both associated with longer shelf life. The M and F genes determining fruit texture (MF/NMF) and flesh adhesion to the stone (clingstone vs. freestone), respectively, were identified very early as endopolygalacturonase (endoPG) genes5,6 (Table 1). They map to a single locus on G4, where two endoPG genes, Prupe.4G261900 and Prupe.4G262200, are involved in their inheritance. The different haplotypes of these two loci and the phenotypes that they determine have been elucidated6,98. Using this information, different molecular markers sets have been developed99 (I. Eduardo unpublished results) to genotype this locus and to identify the alleles that determine the different flesh consistency types, including freestone melting flesh, clingstone melting flesh, clingstone non-melting flesh, and clingstone non-softening flesh.

The SMF phenotype is defined by a slower process of postharvest fruit-softening than the MF types, with “Big Top” being the reference cultivar for the trait100. Using high-density genetic maps of two populations with “Big Top” as one of the parents, two QTLs involved in the trait were identified in G4 and G5, both affecting fruit-softening rate and maturity date101. The QTL on G4 co-localizes with a gene determining the slow ripening trait, a recessive mutation that determines the production of fruit that never ripe102, and with the major QTL determining the maturity date described in section “Phenology (blooming and maturity dates) and climate change adaptation.” The Prupe.4G186800 gene, coding for a NAC transcription factor, was proposed as a strong candidate for the causal gene of these traits48. The second QTL, mapping on G5, was detected only in “Big Top” and also co-locates with a QTL for maturity date, overlapping with a region where other NAC transcription factors are located.

Another trait related with peach flesh texture is SH, which presents a crispy flesh when fully ripe and is known to be controlled by a single gene (Hd/hd). Based on digital gene expression analysis, a YUCCA flavin mono-oxygenase gene (PpYUC11-like, ppa008176m) located on G6 was proposed as a candidate gene for Hd (Table 1), and an SSR in the intron of this gene was identified as a possible diagnostic marker103. Later on, this gene and this marker were confirmed using GWAS33 and the insertion of a transposon-like sequence was detected upstream of the PpYUC11 gene in the hd allele, suggesting its causal effect for the SH phenotype104.

To have a complete picture of the genetic control of peach texture, it is necessary to: (1) identify the alleles of the genes involved in this trait to better understand how these genes interact with each other and with other important genes, such as the ones determining maturity date; and (2) understand how these gene interaction networks are influenced by the environment. Achieving all these goals relies on improved higher-throughput phenotyping methods that increase the power to discriminate the different texture types and the number of samples analyzed. This will require appropriate populations or germplasm collections to be evaluated and the development, where necessary, of plant resources specifically bred to facilitate phenotypic analysis of this important character.

Fruit allergens

Fruit allergy is becoming a significant health issue. There have been frequent reports of peach fruit allergy globally, especially in China and the Mediterranean countries where peach consumption is high and Artemisia pollen allergy is prevalent105. Peach-related allergic symptoms include the oral allergy syndrome, urticaria, gastrointestinal symptoms, and anaphylaxis. Sensitization to peach lipid transfer protein allergens also results in broad cross-reactivity to other fruits and plant foods106. Five allergens in peach have been identified: Pru p 1 (pathogenesis-related protein, PR-10), Pru p 2 (thaumatin-like protein, PR-5), Pru p 3 (nonspecific lipid transfer protein, PR-14), Pru p 4 (profilin) and Pru p 7 (peamaclein, Gibberellin-regulated protein)107,108. With the availability of the peach WGS, all putative peach allergen genes have been located precisely107: a cluster of six Pru p 1 genes, Pru p 2.04, Pru p 4.01, and Pru p 7, are located on peach chromosome 1; Pru p 2.01 on chromosome 3; three members of Pru p 3 in a cluster on chromosome 6; Pru p 4.02 and Pru p 2.02 on chromosome 7; and Pru p 2.03 on chromosome 8109. Gene expression studies of these genes in fruit, leaf, and anther tissues showed differential patterns and fruit specific genes that have been further investigated under different light-shading treatments109,110, demonstrating their variable expression in response to light.

Pru p 1 allergen is cross reactive to birch pollen allergen Bet v 1 in northern of China and Europe, its sensitization resulting in mild oral allergy symptoms. Two isoforms (Pru p 1.01, Pru p 1.02) are expressed in peach fruit and have similar IgE-binding properties111. The Pru p 3 allergen can cause a severe food allergic reaction, while different peach fruit types (peach, nectarine) have a variable content of this allergen in peel and pulp110. There is no genetic diversity of the Pru p 3.01 protein-coding sequence in P. persica. Based on the peach genome sequence, further cloning and sequencing of the upstream region in peach germplasm identified three different allele sequences, with variable frequencies in different subpopulations110. These differences may link to the variation of Pru p 3 content in different cultivars.

There is a need to select hypoallergenic peach cultivars that can be consumed by mild peach allergy patients. Currently about 100 core peach accessions are being evaluated for their Pru p 3 content by a newly developed sensitive method of monoclonal antibody-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay112. Preliminary results showed multiple genetic and environmental factors influencing the content. In general, nectarine and red flesh peaches have lower Pru p 3 content. Quantification of Pru p 1 content is currently in process. Peach fruit allergens accumulate more during fruit development, especially at the ripening stage. Most of these allergenic proteins belong to pathogenesis-related protein families and have biological functions, such as broad disease resistance. They may also be related to fruit softening and fruit quality traits. Combined omics’ tools used in range-wide peach germplasm samples will provide new qualitative and quantitative insights on these allergens and their impact on other agronomic traits.

Disease resistance

Host natural resistance is essential for cost-effective and environmentally safe strategies to address the challenges of day-by-day biotic stress. Whereas, initially, stone fruit tree cultivation relied on seed propagation, it is now done by grafting. While vegetative propagation in perennials has the advantage of growing extensively desirable genotypes, cultivars remain unchanged for centuries while pathogens rapidly adapt to them, causing devastating diseases that are increasingly more difficult to circumvent with chemicals and/or eradication measures. Additionally, moving toward environment-friendly and healthy production systems is strongly desired by consumers, demanding transition to a chemical pesticide-free agriculture with limited impact on the environment.

In this context, the use of resistant cultivars is the foremost breeding strategy for crop protection. Prunus crop species are susceptible to over 70 pests and diseases, but resistant varieties are not readily available and only a few pathosystems are the subject of research programs. Based on the high-quality peach reference genome and tools developed from it, linkage maps were obtained from F1 and F2 populations segregating for resistance to brown rot113,114, green peach aphid115,116,117,118, root-knot nematodes119,120,121,122, fungal gummosis123, bacterial spot124, powdery mildew69,118,125, X-disease126, and sharka18,127,128,129,130. Whereas currently none of the genes and QTLs identified are functionally validated, except for the nematode resistance Ma locus131 (Table 1), these data can be used to implement MAB for resistance as demonstrated for bacterial spot disease and green peach aphid in peach117,132 and sharka in apricot128,133,134. A parallel approach to these structurally based genomic analyses is the functionally based identification of differentially expressed genes, in a context of pathogen infection. This strategy relies on the alignment of the RNA-seq reads to the peach reference genome and on its annotation and gene ontology. Only one of those studies based on the transcriptome analysis generated a peach candidate gene that was confirmed in a bacteria/tobacco heterologous system135. In spite of this difficulty in functionally validating candidate genes associated with resistance traits, one promising strategy is to search, in the peach reference genome, for orthologous genes that were proven to control resistance/susceptibility to the same pathogen in other hosts136. However, this translational research strategy, leveraging knowledge from model plants to Prunus crop species, is limited by (1) the significant challenge of genetically transforming stone fruit trees and (2) the acceptance of genetically modified fruits by consumers. Meanwhile, benefiting from whole-genome resequencing in several peach cultivars and other Prunus species119,137,138,139,140, our knowledge on resistance, pathogenesis-related, and defense elicitor gene diversity and evolution in Prunus species is increasing.

Breeding for resistance to pests and pathogens in stone fruit crops encounters the usual problems associated with breeding perennial plants. This process is significantly hampered by the complexities inherent to tree testing and evaluation, our lack of knowledge of the pest/pathogen biological interaction, and the diversity and genetic determinism of the target resistance traits that is often quantitative. On top of that, screening for pathogen/pest resistance in stone fruit tree germplasm collections is a very time-consuming and effort intensive task. This likely explains the low number of pests and pathosystems under study, in the past decade. Therefore, there is a great need for academic and practical attention to this area and the development of transnational, high-throughput phenotyping platforms.

The incorporation of resistance genes in current stone fruit breeding programs from related wild species is a promising option. However, it requires significant efforts to identify the valuable germplasm that is unfortunately scarce in the stone fruit crop species. Indeed, excluding resistance mechanisms described in wild P. kansuensis, P. davidiana, and P. armeniaca species115,119,141, there is very little information about resistance sources in non-crop Prunus relatives. This calls for a more systematic survey of the extent Prunus wild relatives around the world, as well as their phenotypic characterization for various resistance traits. These materials could be included in the above-mentioned platforms for high-throughput phenotyping. Once new sources of resistance are identified in wild relatives, the next step is the introgression of the genetic factors linked to resistance into elite Prunus cultivars through interspecific crosses. Yet, there are inherent difficulties in doing so that can be minimized by using a marker-assisted introgression (MAI) approach recently proposed and described in section “Applications of genome information in Prunus improvement: MAB, MAI, genomic selection, and visualization of the genome-wide genetics of elite individuals” of this paper142. Genetic analysis of domesticated and non-domesticated stone fruit genomes may identify the presence–absence variations contributing to trait variation. Toward this goal, a groundbreaking initiative would be the construction of a Prunus pan-genome, based on already-sequenced Prunus genomes143,144. This Prunus pan-genome would promote and accelerate the development of appropriate genomic tools for all Prunus species, including wild relatives.

Whereas all mentioned resistance studies deal with one single pest or pathogen at a time, fruit trees are challenged in the orchard by a cohort of pests and pathogens, in combination or successively. Moreover, plants in the field are under constant threat of multiple abiotic and biotic stresses. Very complex physiological and molecular interactions take place, resulting in unique response(s) of the plants to withstand the combined effect of these stresses. In such situations, plants can show either enhanced or reduced pest/pathogen resistance. While the combined effect of biotic and abiotic stresses has been extensively studied in annual crops, only one study dealt with a perennial host (Populus sp.) and none on fruit trees145. This establishes a need for studies combining resistance mechanisms to multiple pests and pathogens as well as resistance/tolerance to both biotic and abiotic stresses. Hence, future research programs should explore the utilization of association mapping approaches based on high-throughput genotyping of stone fruit, wild and crop, germplasm collections that will be tested for a variety of biotic and abiotic factors.

Today, epigenetics has become a crucial research field in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses, especially in long-lived species such as fruit and forest trees. Plants subjected to contrasting environments have evolved different epigenomes, suggesting that epigenomes are remodeled in plants under stress, such as pathogen and herbivory attacks146,147 contributing to long-term adaptation34. Recently, several studies provided valuable information related to the epigenetic control in plant stress adaptation. Epigenetics refers to the variability in gene expression occurring as a result of modification of DNA and associated proteins. Hence, epimutations are often associated with specific sequence contexts, including tandem and inverted repeat or TE insertions that are thought to attract DNA methylation to nearby loci34,148. This feature, together with comparative epigenomic studies, may provide an interesting way to screen for new epialleles associated with responses to biotic stress149. However, such whole-genome surveys of epigenome variation are seriously missing in stone fruit tree species research. We need pilot experiments conducted by a coordinated action of laboratories that combine whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq, and transcriptome analysis in order to successfully map epigenetic factors controlling responses to biotic/abiotic stresses and, in consequence, identify new phenotypic diversity.

Tree architecture

Tree architecture can have a substantial impact on yield and management costs and also is of interest to peach ornamental and rootstock breeding programs. Different peach tree architectures have been described including the standard spreading form, brachytic dwarf, semi-dwarf, compact, spur-type, narrow-leaf, weeping, columnar and upright, or semi-columnar150,151.

Brachytic dwarfing in peach is controlled by a single gene, Dw/dw, located on chromosome 6 that was cloned using a bulk segregant analysis approach combined with genome resequencing152. The responsible allele is a loss-of-function mutation in a gibberellic acid receptor (PpGID1c) gene (Table 1). A different allele of this gene also causing brachytic dwarfism has been identified153. Another gene responsible for dwarfing in peach, Tssd/tssd, causes the temperature-sensitive semi-dwarf phenotype and has been fine mapped to a region spanning 500 kb on G3, where 69 genes are annotated in the Prunus reference genome154.

Trees with weeping habit or, by contrast, with branches with vertical growth (pillar) have been identified. For both traits, the genes causing their atypical branch growth orientation have been identified and characterized. In the case of weeping habit, the trait is determined by a single gene (Pl/pl) located on G3118. Using a genomic sequencing approach, a SAM domain gene (ppa013325; Prupe.3G200700) affecting branch orientation has been recently identified and functionally validated by silencing in P. domestica trees155 (Table 1). The trait characterized by vertically oriented branches called broomy or pillar is determined by a major gene (Br/br). The heterozygous phenotype has a distinctive phenotype called upright. A PpeTAC1 candidate gene for Br has been identified on G2 coupling bulked segregant analysis with NGS156 (Table 1). This gene is a putative ortholog of rice TAC1 (tiller angle control 1). The mutation causing the pillar phenotype is an insertion located in exon 3 of PpeTAC1 (ppa010082; Prupe.2G194000) causing a stop codon. RNA interference (RNAi) silencing of this gene in P. domestica produced trees with a more extreme pillar phenotype than the one described in peach157.

All the available knowledge of genes controlling these traits and molecular markers to select them makes it possible to efficiently breed new cultivars with characteristics more adapted to different growing practices, including the possibility of high-density plantations and mechanization158. Furthermore, other traits related to root architecture need to be included in the global picture. Overexpression of one of these genes, deeper rooting 1 (DRO1), in P. domestica resulted in trees with deeper roots159 that could produce plants more adapted to drought.

The gametophytic self-incompatibility (GSI) system of Prunus

Fertilization and seed formation are essential for fruit production in Prunus because stone fruit and almonds are unable to bear fruit parthenocarpically. Special attention, therefore, has been given to the Prunus GSI system and extensive studies have been conducted to elucidate physiological, genetic, and genomic aspects of GSI. During the past two decades, the specificity determinants of pistil (S-ribonuclease; S-RNase) and pollen (S haplotype-specific F-box protein; SFB) in Prunus have been identified by classical protemoics and genomics techniques based on two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and chromosome walking, respectively160,161. Identification of the pistil S and the pollen S determinants led to the development of PCR-based S genotyping and marker-assisted selection for self-compatible (SC) individuals. Furthermore, a series of molecular and genetic analyses of Prunus SC S haplotypes revealed the possible existence of a distinct recognition mechanism in the S-RNase-based GSI system in Prunus8,160.

Recent studies utilizing WGS information in Prunus shed light on the evolution of the S locus and establishment of the Prunus-specific GSI recognition mechanism. Evolutionary paths of the establishment of Prunus S-RNase and SFB were investigated by tracking their gene duplication patterns162. Phylogenetic analysis and estimation of proxy ages for the establishment of S-RNase and its homologs in several rosaceous species showed that the divergence of S-RNase in the subtribe Malinae and the genus Prunus predated the gene in the most recent common ancestors of Rosaceae species. Furthermore, the duplicated S-RNase-like genes were accompanied by duplicated pollen S-like F-box genes, suggesting segmental duplications of the S locus. Analysis of the expression patterns and evolutionary speed of duplicated S-RNase-like genes in Prunus suggested that these genes have lost the SI recognition function, resulting in a single S locus. Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis with SFB and its orthologs in other angiosperm genomes indicated that Prunus SFB does not cluster with the pollen S of other plants and diverged early after the establishment of the Eudicots29. Prunus SFB likely originated from a recent Prunus-specific gene duplication event. Transcriptomic and evolutionary analyses of the Prunus S paralogs are consistent with the establishment of a Prunus-specific SI system and the possibility of subfunctionalization differentiating the newly generated SFB from the original pollen S determinant. The S loci in the current Rosaceae species might have evolved independently from the duplicated S loci, which could explain the presence of genus-specific SI recognition mechanisms in the Rosaceae.

Recently, WGS information has been further utilized to identify pollen part modifiers specifically present in Prunus63,163. Availability of WGS information in diverse species of Prunus and resequencing information of cultivars and strains in a given Prunus species will further contribute to elucidating the Prunus-specific GSI system.

Applications of genome information in Prunus improvement: MAB, MAI, genomic selection, and visualization of the genome-wide genetics of elite individuals

Routine application of MAB has long been the main avenue to which stone fruit breeders have expected to benefit from genomics advances. The ability to predict the phenotype before it is expressed and especially in the early stages of each plant’s life is of high value in crops that can take ≥5 years before the phenotype can be assessed in the field. Several collaborative attempts to translate that vast information of QTL and gene analysis in user-friendly informative DNA tests have been attempted164,165 (www.fruitbreedomics.com; www.rosbreed.org). However, only a limited number of reports on development, validation, and successful implementation of MAB have been published so far79,87,94,102,133,166,167,168,169,170,171,172. To aid in publicly sharing DNA information, the promises, progress, and prospects of using DNA-based information in breeding in Rosaceae and other horticultural crops have been recently summarized173,174,175 and steps to translate promising QTL information to a trait-predictive DNA tests have been proposed176. With additional Prunus genome sequences being released, an exponential increase in discovery of marker–trait associations is expected. A shift in selection approaches to molecular genotyping and DNA informed breeding efforts have proven useful and are now economically feasible on much larger scales.

The variability of wild and cultivated compatible relatives of Prunus species is an enormous reservoir that may contain useful alleles to be integrated into target species, particularly those that have less diversity such as the peach20,177. However, this variability has seldom been used in Prunus breeding because of: (1) poor knowledge of the inheritance of traits of interest that could be introgressed from exotic sources; (2) limited availability of interspecific crosses and incomplete knowledge of intercrossability among species, and (3) the several generations required to recover an elite genetic background to result in commercially valuable fruit tree cultivars. A method to address these drawbacks, MAI, was proposed and tested successfully in peach × almond crosses142. MAI consists of generating a large BC1 population (N > 1000) from an interspecific hybrid. A small collection of seedlings (15–25) with a few introgressions (the “prIL set”) and overall containing the whole donor genome can be selected from this progeny. These individuals, when backcrossed again or selfed, will produce with reasonable frequency genotypes with the genetic background of the recurrent species, peach in this case, and a single fragment in homozygosis or heterozygosis of the donor parent (almond). In the case of the peach × almond progeny used, the first individuals with a single introgression were extracted 9 years after the beginning of the experiment142. Currently, a collection of introgression lines (ILs) heterozygous or homozygous for a single introgressed almond fragment is available with 85% and 45% coverage of the almond genome, respectively (P. Arús unpublished results). Phenotyping the prIL set is also an opportunity for identifying, with low resolution, the genome positions of major genes with dominant or additive almond alleles. The characters of interest can be examined in a genetic background very close to that of the recurrent parent and therefore with limited influence of the donor variability at other genetic regions. This situation makes the prIL set an interesting tool for assessment of the variability supplied by an exotic genome and is an affordable means for long-term storage of the exotic genome in an elite background, often only one generation away from a commercial cultivar. Implementing MAI approaches to other crop × wild or exotic Prunus species is an interesting objective for ensuring future availability of the overall diversity of this genus for breeding purposes.

Genomic selection is a molecular genotyping technique that shows promise in fruit tree crops for enhancing breeding efficiency via increased prediction accuracy and selection intensity and decreased generational interval178,179,180. Application of genomic selection in plant breeding is still fairly new and requires further investigation of the most appropriate model(s) and the optimal number of markers and plants to use181,182. Preliminary reports on the factors affecting accuracy of genomic prediction in fruit crops suggested importance of relatedness between the reference and validation individuals, with prediction accuracy increasing in highly related material178,180. In addition, multicycle analysis in strawberry180 and peach179 showed a steady increase of prediction accuracy for all traits as data were aggregated across cycles in the reference population.

Genetic architecture of the trait influences the size of the reference population needed to accurately estimate the SNP effects. The smaller the largest SNP effects are, the larger a reference population is needed178. Modeling for the optimal number of markers in apricot61 and strawberry180 suggested that prediction accuracy of 88–97% is achieved with ~500–1000 informative, non-redundant, randomly distributed markers. Evaluation of the feasibility of genomic selection in peach for highly polygenic traits linked to yield and fruit quality suggested similar prediction accuracy with over 60% for fruit weight, sugar content, and titratable acidity179.

Genomic information can also be used to estimate genetic relationships among germplasm populations by modeling the performance of an individual in different environments183,184 and to estimate an individuals’ breeding value49,179,184,185. High correlation (0.88; P < 0.0001) between predicted genomic breeding value and fruit size was observed in cherry185. An initial study on predicting genomic breeding value for fruit weight, sugar content, and titratable acidity in peach showed promising results for application of genomic selection in peach breeding programs179.

A new opportunity is available for breeders to effectively access and make decisions on the genetics of their germplasm. The breakthrough has four components. The first is a technological advance in genotyping technologies that efficiently provide genome-wide genetic polymorphism data; SNP arrays are particularly useful here because the same loci are assessed on all plants. The second component is conceptual, giving explicit attention to each elite germplasm individual (parents, selections, and cultivars) just as breeders do. The common way to deal with large genotypic datasets is a quantitative summary across the germplasm, but this approach easily overlooks each germplasm individual. The third component is an analytical synthesis of genome-wide genotypic data into three genetic vectors of breeding relevance: (1) allelic variation (patterns of similarity among alleles within each locus); (2) linkage (patterns of recombination among loci within each individual); and (3) relatedness (patterns of shared ancestry among individuals within a population). Together, the patterns of alleles over loci over generations can provide emergent genetic knowledge on elite germplasm individuals to improve the precision with which individuals are used in breeding. The key qualitative leap in information now available is the positioning of all recombination events that have led to each plant. SNP datasets of pedigree-connected material must be carefully curated by removing errors, ascertaining all pedigree connections, phasing each individual, and imputing missing data186. Haploblocking (section “Haploblocking Prunus genomes”) also helps. The fourth component is enabling user experience of the holistic “genotype” of each elite individual. It is proposed that sensory experience of DNA information that focuses on elite individuals, just as for phenotypic information, would help breeders better understand what they have and then target development of what they want. While DNA-based genetic information cannot yet be heard or tasted, one way for breeders to “experience the genotype” of an elite individual is by seeing it. Visual aids are well recognized as vital tools for transmitting information for long-term memory retrieval and empowering users to leverage their creativity and understand large data patterns187. While improvements in graphical genotyping software are desired as the fifth component to facilitate routine use of genome-wide genetic information in breeding decisions, in the meantime ad hoc collation of the above information can be made as “haplotype mosaics” (Fig. 3). Software is in development to display a circular format for haplotype mosaic visualization. In sweet cherry, visualizing the genetics of elite genomes has recently been used to reveal new pedigree relationships among cultivars and trace origins and distributions of valuable trait locus alleles in ancestors and parents188.

Segments that “Rainier” inherited via its parents from its three specified ancestors are displayed across the eight chromosomes of sweet cherry. In some cases, these ancestral segments are homozygous, highlighting consequences of inbreeding and signifying common ancestry in generations behind known ancestors. Trait locus alleles are indicated with phenotypic effects and ancestral origins; despite the commercial success of “Rainier,” it can be seen that there is still much to be improved. These results were obtained from single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data curation and pedigree ascertainment by L. Cai and C. Peace using the RosBREED cherry 6K SNP array v1 on a U.S. breeding germplasm set (n ~ 500)21. Diagram is from Peace et al.175

Development of biotechnology tools: genetic transformation and gene editing

The lack of efficient regeneration systems in Prunus is a primary limitation for stable genetic transformation procedures and generation of transformant individuals. New breeding techniques (NBTs), involving approaches such as RNAi, DNA methylation, and gene editing, could overcome the monolithic requirement of having a final T-DNA-modified individual. Novel techniques in gene transfer have a rediscovered value due to simple requirements such as an efficient transient expression189 or a direct intake of pre-assembled190 editing reagents into the cell. For this reason, transient expression systems, protoplast regeneration, somatic embryogenesis, and organogenesis regeneration procedures are currently being optimized for NBT application.

The availability of genome drafts in Prunus species enables advances toward improved and safer applications involving NBTs. Regarding gene editing technology, prior knowledge of the genome can help to ensure system efficiency and specificity. The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR)/Cas9 system, discovered as an adaptive line of defense against viral infection in Archaea191, is the most common gene editing technique that allows for the direct generation of sequence modifications in the genome. Targeted mutagenesis by this tool involves making guide RNAs (gRNAs) that target customized sequences in the genome to direct the Cas9 nuclease activity to generate double-strand breaks adjacent to the gRNA-joined location. gRNA refers to a short synthetic RNA composed of a scaffold sequence necessary for Cas-binding and a user-defined 20 nucleotide spacer that determines the genomic target to be modified. The target sequence recognized by the spacer will be a protospacer sequence, located contiguous to an adjacent motif recognized by Cas9 required for DNA cleavage, that is an NGG nucleotide arrangement called protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). Currently, new nucleases replacing Cas9 are the focus of new research that uses different PAM motifs192.

By computing on described genomes, PAM datasets and their contiguous regions can be reviewed and summarized in datasets. In this way, several datasets for gRNA and PAM required in DNA editing have been described and used for on-target and off-target predicting activity of gRNAs inside a genome193. In the case of Prunus spp., P. mume datasets with information about the target sites of Cas9 (i.e., NGG) and newer nucleases such as Cpf1 (which uses TTTNs and TTNs as PAMs) are available at the CRISPR-Local194 website (http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/cgi-bin/CRISPR-Local/download). Similarly, based on the peach and sweet cherry genomes, a Cas9 gRNA designer and analyzer for both species is available (www.fruit-tree-genomics.com/biotools).

The system CRISPR/Cas9 has been successfully used in plants and delivery of editing components into the plant cell has been mostly achieved by their stable integration into the genome by gene transfer techniques relying on Agrobacterium-mediated transformation195. Efforts to edit individuals without foreign DNA insertion into the genome have involved the delivery of assembled ribonucleoprotein editing reagents190. A different approach implies the delivery of DNA-replicons using disarmed or “deconstructed” viruses189, which allows for a high copy number in the cell without the insertion of the replicon into the plant genome.

Efficacy of the above-mentioned techniques in vivo relies on the knowledge of the specific target sequences and, ideally, of whole-genome information to prevent secondary effects on eventual off-targets. For this reason, transient expression assays have become relevant as screening systems prior to a “precise breeding” full-path experimentation. These procedures are relevant because they avoid the technical difficulty and the time needed for whole plant generation, which is a major restriction in Prunus9,196. Protocols based on the use of explants such as leaf discs, stem segments, or even whole plants have been achieved in other woody species such as grapevines197,198. Nevertheless, these approaches are restricted to a few Prunus species such as P. domestica199 and P. salicina200 in experiments that can be considered preliminary assays that later led to stable transformation procedures201,202. In P. persica, different tissues were successfully used as explants for biolistic-mediated β-glucuronidase gene expression203 in the search for a stable transformation procedure. In addition, protoplast procedures in P. avium204 and P. avium hybrids205 can be proposed as optimal tools for gene editing capability for in vivo evaluation. This technique could help to overcome chimerism, a significant issue in woody plant genetic transformation.

A significant amount of research has been carried out regarding Prunus spp. regeneration using different explants and approaches, and optimal conditions for this process are determined by many factors9. Whereas leaf explants can lead to adequate regeneration systems in several members of the Rosaceae family206, extremely recalcitrant species in Prunus limit regeneration mostly to using seed explants9. Recently, leaf explants of P. domestica have shown increased adventitious shoot production by constitutive expression of the class I KNOX gene from corn207.

Improved regeneration efficiencies have been obtained in other species. In sweet cherry varieties, more efficient methods were described using leaf and nodal segments208 and mature cotyledons209. Better results have been reported in other commercially important genotypes, including sour cherry210,211, black cherry (P. serotina)212, and several cherry rootstocks211,213,214. In another example, a complete pipeline of methods for transformation and regeneration of transgenic apricot plants from “Helena” leaves has been described215,216. In all cases, researchers used A. tumefaciens EHA 105 for gene transfer.

Experimental procedures exploiting RNAi approaches allowed the generation of Prunus necrotic ringspot virus (PNRSV) resistant individuals of a cherry rootstock217. Grafting of these individuals demonstrated small RNA transport from rootstock to scion, resulting in “Emperor Francis” scions becoming resistant to PNRSV218. In this way, the use of Prunus genotypes currently suitable for genetic transformation can be proposed as small RNA generators (donors) for systemic transmission of resistance through transgrafting to compatible scions from different genetic backgrounds, directing either systemic sRNA-directed gene silencing or sRNA-directed DNA methylation.

Existing and new bioinformatics tools and resources for Prunus