Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the esophagus triggered by immune hypersensitivity to food. Herein, we tested whether genetic risk factors for known, non-allergic, immune-mediated diseases, particularly those involving autoimmunity, were associated with EoE risk. We used the high-density Immunochip platform, encoding 200,000 genetic variants for major auto-immune disease. Accordingly, 1214 subjects with EoE of European ancestry and 3734 population controls were genotyped and assessed using data directly generated or imputed from the previously published GWAS. We found lack of association of EoE with the genetic variants in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, II, and III genes and nearly all other loci using a highly powered study design with dense genotyping throughout the locus. Importantly, we identified an EoE risk locus at 16p13 with genome-wide significance (Pcombined=2.05 × 10−9, odds ratio = 0.76−0.81). This region is known to encode for the genes CLEC16A, DEXI, and CIITI, which are expressed in immune cells and esophageal epithelial cells. Suggestive EoE risk were also seen 5q23 (intergenic) and 7p15 (JAZF1). Overall, we have identified an additional EoE risk locus at 16p13 and highlight a shared and unique genetic etiology of EoE with a spectrum of immune-associated diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the esophagus triggered by immune hypersensitivity to food. Multiple lines of evidence, including molecular transcript profiling, cytokine expression, and genetic studies have highlighted its close relationship with type 2 immune responses, and EoE is now considered a chronic form of food allergy [1]. EoE susceptibility is linked to a genetic factor at 2p23, the CAPN14 gene, which has tissue-specific expression in the esophagus [2, 3]. This genetic association has been replicated in multiple cohorts [3,4,5], adding credence to the importance of the 2p23 genetic association and resulting in a combined P value of 1.7 × 10−10. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have also identified EoE genetic risk loci that were linked to other allergic diseases [6]. For example, genetic variants at 5q22 encoding TSLP and WDR36 have been associated with allergic sensitization, asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and EoE, suggesting that these loci contain variants that participate in the allelic regulation of a molecular pathway that is central to the etiology of allergic disease [2, 4, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Likewise, the 11q13 EoE risk locus encoding EMSY and LRRC32 has been robustly replicated in studies of EoE [4, 15, 16] and is also associated with atopic dermatitis [7, 17,18,19], asthma [9, 11, 20], allergic sensitization [20], allergic rhinitis [11], and inflammatory bowel disease [21]. Indeed, genome-wide approaches have demonstrated significant overlap of some EoE genetic risk loci across allergic diseases [1,2,3, 22].

The Immunochip was designed to genotype and fine-map genetic risk loci that were established for major immune-associated diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, psoriatic arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and celiac disease; notably, the latter has an increased prevalence in patients with EoE [23]. As the introduction of the Immunochip in 2011, its use has contributed to a marked increase in known susceptibility loci and the comparison of susceptibility loci between phenotypes [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Herein, we probed the genetic etiology of EoE with multiple objectives, including (1) determining whether EoE risk loci would be shared with these immune-mediated diseases that have already been subjected to intense investigation; (2) identifying genetic variants with plausible function, as the Immunochip was enriched for functional variants; and (3) fine-mapping the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region, as this region confers risk for other immune-mediated diseases. We report genetic analysis of EoE using the Immunochip platform and the largest cohort of subjects with EoE subjected to genetic analysis to date.

Results

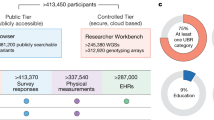

To evaluate EoE risk at genetic loci associated with a variety of immune-associated diseases, 1214 subjects with EoE and of European ancestry and 3734 population controls were genotyped using the Immunochip candidate genotyping array [23].

After stringent quality control based on Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium and a call rate of >99% and lack of batch effect (described in Methods), 79,405 genetic variants had minor allele frequencies >1% and were used for this association study. The subjects with and without EoE were assigned to either the Local or External study cohorts (Supplemental Table 1). The Local cohorts included EoE patients from the Cincinnati Center for Eosinophilic Disorders (n = 966) and controls from the Cincinnati Genomic Control Cohort (n = 641). Controls from the Lupus Family Registry and Repository (n = 3093) and patients with EoE recruited outside of Cincinnati through the National Institutes of Health Consortium of Food Allergy Researchers (CoFAR) (n = 244) were assigned to the External cohort. Initially, one locus at 6p21 with genome-wide association (P < 5 × 10−8) and one locus at 16p13 with suggestive significance (P < 10−7) were identified (Fig. 1, Table 1). Next, independent experimental association was sought from the published GWAS by assessing the statistical significance of the most highly associated variant at each locus from the Immunochip analysis in the GWAS population after removing all subjects who overlapped between the two studies from the GWAS analysis [3] (Fig. 1, Table 1, Supplemental Table 1). No association was identified at 6p21 in the non-overlapping GWAS cohort; however, the genetic risk association at 16p13 was validated, resulting in genome-wide significance of the combined cohorts (P = 2.05 × 10−9) (Table 2). A logistic regression analysis demonstrated a single genetic effect, with all association in the locus accounted for by the genotype of rs12924112 (Fig. 2). This particular genetic variant was located in the 20th intron of CLEC16A.

Manhattan plot of the P values obtained from the Immunochip association analysis. Data are from 1210 subjects with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) and 3734 controls over 79,405 genetic variants with minor allele frequencies (MAFs) greater than 1% in the subjects with EoE. The −log10 value of each probability is shown as a function of genomic position on the autosomes. Genome-wide significance (red dashed line; P ≤ 5 × 10−8) and suggestive significance (solid blue line; P ≤ 1 × 10−7) are indicated

Genetic association of variants at the 16p13 loci with EoE risk. a P values (−log10) from the genetic association analysis of genotyped and imputed variants are plotted against the genomic position of each genotyped (blue) and imputed (red) single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) on the x axis on chromosome 16. b P values (−log10) from the genetic association analysis adjusting for the association of rs12924112 of genotyped and imputed variants are plotted against the genomic position of each genotyped (blue) and imputed (red) SNP on the x axis on chromosome 16. Genes in the region are shown below. Position is given relative to Build 37 of the reference genome. Black lines indicate the recombination rates determined using subjects of European ancestry from the 1000 Genomes Project

The 16p13 locus has been associated with ten other immune-associated phenotypes ranging from atopic dermatitis and asthma with hay fever to the autoimmune diseases systemic lupus erythematosus and type 1 diabetes (Table 3) [11, 33, 34, 36, 38, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. On the basis of the linkage disequilibrium between the most highly associated disease protective variant in other diseases and the lead EoE 16p13 protective variant, variants decreasing risk for EoE also decrease risk for type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, primary biliary sclerosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (Table 3). The lead variants reported for atopic dermatitis and asthma with hay fever were in relatively weak linkage disequilibrium with the EoE risk variants (Table 3).

The 16p13 locus encodes the genes CLEC16A, DEXI, and CITTA. These genes are known to be expressed in the esophageal mucosa [50,51,52,53] at levels similar to other tissues. Indeed, expression of the three genes was found in the esophageal biopsies of subjects with and without EoE (Fig. 3a). CLEC16A and DEXI were expressed in esophageal epithelial cells and were found to not be modulated by IL-13 treatment, while CITTA was not expressed in esophageal epithelial cells (Fig. 3b). CLEC16A, DEXI, and CITTA are also expressed in various immune cell subsets (Fig. 3c) [54, 55]. In monocytes, the EoE risk haplotype at 16p13 is associated with increased expression of DEXI in monocytes [56]. The same EoE risk haplotype has also been associated with increased expression of CLEC16A in B cell lines [57]. This suggests that genotype-dependent expression of DEXI and/or CLEC16A might lead to increased risk of EoE in patients with the 16p13 risk alleles.

Expression of genes at the 16p13 locus. a RNAseq expression of CLEC16A, DEXI, and CIITA mRNA from esophageal biopsies (Control n = 10, EoE n = 10). No significant differences were identified between Control and EoE. b RNAseq expression of genes from esophageal epithelial cells in air-liquid interface culture system with or without IL-13 stimulation for 5 days (n = 3 wells per group). For a and b, bars represent the mean and error bars represent the standard deviation. No significant differences were identified between no treatment and IL-13 treatment. c Barcode x-score relative microarray expression of CLEC16A, DEXI, and CIITA in various human immune cell subsets downloaded from http://biospgs.org/ (ref. [48]). Reads per killobase of transcript per million mapped reads, RPKM. Data are representative from multiple cellular subtypes in the Primary Cell Atlas dataset

Genetic variants at the 5q23 and 7p15 loci demonstrated modest association in the local and external Immunochip cohorts, but they failed to be reproduced by data from a previous GWAS analysis. Although they did not pass the threshold set by this study for significant association, they remain candidates to be further evaluated in subsequent studies. The suggestively associated EoE risk variants at the 5q23 locus are located in an intergenic region that is 14 million base pairs away from the EoE risk locus at 5q22 that encodes the TSLP and WDR36 genes with no linkage disequilibrium (R2 = 0.0005). The 7p15 locus near the gene JAZF1 has also been identified as a susceptibility locus for systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis [58,59,60,61,62]. JAZF1 is also known as TIP27, and it encodes a transcription factor with three zinc fingers that often represses transcription [63].

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC), the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) complex in humans, is a region of the genome on chromosome 6 that encodes genes that regulate antigen presentation to T cells. This region contains the most robustly and reproducibly associated risk variants for many immune-associated diseases including autoimmune and auto-inflammatory diseases; these genetic risk variants usually affect amino acid usage in the MHC molecules. The Immunochip was specifically designed to directly genotype variants across this locus, and its use has allowed teams to identify the genotype-dependent usage of MHC subtypes in diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus [25], type 1 diabetes [64], and psoriatic arthritis [65]. Consistent with the three previous GWAS of EoE, we did not identify association of genetic variants that are located inside the MHC class I, II, or III genes. We did find association of rs599707 in 6p21 in both the local and external cohorts assessed on the Immunochip (Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 1); however, none of the variants in linkage disequilibrium (r2 greater than 0.8) changed amino acid usage in any gene. Based on the power analysis of the combined cohorts from the previous GWAS and present Immunochip studies (Supplemental Fig. 2), we can definitively confirm that there is no HLA association with EoE that is driven by variants with effect sizes greater than 1.4 or MAFs greater than 20%.

Discussion

We have probed the genetic basis of EoE focusing on genetic variants involved in a wide range of auto-immune and/or inflammatory diseases. We have identified one new genome-wide significant EoE risk locus at 16p13, a region encoding the CLEC16A, DEXI, and CITTA genes, and nominate three additional suggestive loci that warrant further analyses. The 16p13 finding identifies a region of the genome that includes genetic risk variants associated with numerous immune-associated diseases including both allergic and autoimmune diseases; however, it is notable that the vast majority of risk loci on the Immunochip did not reveal association with EoE consistent with the uniqueness of the genetic etiology. The specific risk haplotype at 16p13 was not shared with atopic disease related to EoE based upon LD of the most highly associated variants for each phenotype, suggesting different genetic effects are driving the shared association at 16p13.

This study was designed to identify EoE genetic risk loci that demonstrated association in internal and external cohorts in addition to the previously published GWAS at a group of loci nominated by previous studies of immune-associated diseases. The ImmunoChip does not include previously reported EoE-risk loci, so we are unable to assess the established 2p23, 5q22, or 11q13 risk loci. The limited number of samples that remained in the GWAS cohort after removing overlapping individuals may explain why some of the suggestive associations from the Immunochip analysis were not validated when assessing the independent subjects in the GWAS cohort (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Specifically, after removing 542 overlapping cases with EoE and 587 overlapping controls from the GWAS of 9982 subjects, only 194 cases and 8659 controls remained leaving the study with only 30% power to detect a locus with a large effect size (odds ratio of 2.0) and high MAFs (40%). This study also lacked the power to divide the patients with EoE into sub-classifications (e.g., patients with EoE responsive to proton pump inhibitors); however, future studies designed to identify genetic variants associated with the clinical presentation of EoE would be valuable.

The genotyping at the HLA region of the human genome is particularly dense on the Immunochip [23]. Over 200 diseases have robust HLA associations, especially autoimmune diseases [66] with effect sizes ranging from 1.3 to 3.0. It is notable that no association has ever been identified for EoE despite numerous genome-wide studies and this Immunochip study. Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and celiac disease are three gastrointestinal diseases with strong HLA associations [67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. In each of these non-EoE gastrointestinal diseases, a robust genetic association with variants across HLA are a hallmark of nearly every Immunochip and GWAS to date. Celiac disease is enriched in EoE patients [74,75,76,77,78]; likewise, patients with celiac disease have a 25% increased risk of developing EoE [76]. Indeed, celiac disease and EoE share features including being food antigen driven, involving a defective epithelial barrier, and resolving upon removal of causal foods. The lack of highly associated EoE risk variants that change MHC subtypes through nonsynonymous disease risk polymorphisms remains a striking differentiating factor for EoE. rs599707 at 6p21 is an expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) for numerous HLA molecules in monocytes (HLA-DPB1, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1, HLADRB1, HLA-C, and HLA-H, tag SNP: rs3131379, r2 = 1 in people of European ancestry) [56]. Though the 6p21 locus demonstrated genome-wide association in the two cohorts assessed on the Immunochip, these variants were not identified as associated in an independent set of subjects with and without EoE assessed with the comprehensive OMNI5 array [3]. The HLA region is encoded from 6p21 and spans 3 million base pairs; the region is genetically complex with many independent haplotypes of variants in strong linkage disequilibrium [79]. The 6p21 EoE risk locus tagged by rs599707 is a highly polymorphic haplotype in the HLA that encodes 71 genes. Only 3 genotyped and no imputed genetic variants in the region reached genome-wide significance, and 2 out of 3 of these variants failed quality assessment on the OMNI5 array [3] (Supplemental Fig. 1, Supplemental Table 2). Furthermore, the genotyped variant that passed quality assessment on both the Immunochip and GWAS studies had opposite effects in the two studies, i.e., risk allele in the Immunochip study was protective in the non-overlapping cohort genotyped in the GWAS. While we have no reason to remove these variants from the analysis, two other pieces of data supporting their spurious association are the fact that the variants are not in linkage disequilibrium with each other (Supplemental Fig. 1B) and variants that are in linkage disequilibrium with the “associated” variants in the 1000 genomes project in people of European ancestry are not associated at the same level of robust significance (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Given the lack of GWAS validation and the small number of associated variants at the locus, this study presents 6p21 as a candidate risk locus for EoE that needs further study before any robustly conclusion can be established. If the rs599707 EoE risk genetic association is replicated in an independent dataset, this genotype-dependent expression of these HLA molecules should also be assessed in the context of subjects with EoE.

We have identified novel genome-wide association of EoE with variants at 16p13. This region was included in the Immunochip design based upon previous association in studies of multiple sclerosis and diabetes type 1 [23, 67, 80, 81]. Other allergic diseases also have genetic risk variants at the 16p13 locus, but it is notable that the genetic variants associated with EoE and other allergic diseases are not in linkage disequalibrium with each other (Table 3). The EoE risk variants at 16p13 are in strong LD with risk variants for multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes (Table 3). Among the genes at 16p13, CLEC16A is widely expressed across the immune system and contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM). CLEC16A is also expressed in esophageal epithelial cells of subjects with and without EoE. Recently, CLEC16A has been shown to negatively regulate autophagy via modulating mTOR activity [82]. DEXI is named on the basis of its identified dexamethasone inducibility in airway epithelia [83]. DEXI is also differently expressed in the lung tissue of patients with emphysema compared to normal lung tissue. Genotype-dependent expression of both CLEC16A and DEXI have been identified [56, 57], and chromatin looping from the EoE risk variants shared with type 1 diabetes has demonstrated looping back to the promoter of DEXI [84, 85]. CIITA acts as main positive transcriptional regulator of the class II major histocompatibility complex genes [86,87,88]. While not expressed in esophageal epithelial cell cultures (Fig. 3b), it is found in the esophageal biopsies of patients with and without EoE (Fig. 3a), perhaps due to expression infiltrating immune cells. Further, the regulation of antigen presentation could be critical in the development of atopy. Thus, CLEC16A, DEXI, and CITTA each remain strong candidates for mediating EoE disease risk.

Altogether, this study presents a newly established EoE risk locus at 16p13 and demonstrates a relatively unique genetic etiology compared with nearly all autoimmune disease susceptibility loci.

Methods and materials

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed as previously described [3, 22] on the Illumina Immunochip genotyping array using Infinium2 chemistry. Genotypes were called using the Gentrain2 algorithm within Illumina Genome Studio.

Subjects included in the genetic analysis

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) and all participating sites that were part of the NIH Consortium of Food Allergy Research (CoFAR) EoE Cohort (Mount Sinai Medical Center, University of North Carolina, Johns Hopkin’s University, University of Colorado Health Center/National Jewish Research Center, and Arkansas Children’s Hospital). Guardian informed consent was obtained for all participants under eighteen years of age in this study for the purpose of DNA collection and genotyping. Cases were confirmed by a physician to fulfill the diagnostic criteria for EoE. EoE is defined as peak eosinophil count ≥15 eosinophils/high-power field in esophageal biopsy sections; 30% of CCHMC and 51% of CoFAR subjects who were genotyped on the Immunochip had proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy before the diagnostic endoscopy. A similar strategy was used as in a previous GWAS [3]. Control subjects (non-EoE) included the subjects with self-reported European ancestry in the Cincinnati Genomic Control Cohort CCHMC (n = 641, age range 2–18 years) [89] and an external control cohort (non-EoE) acquired from the Lupus Family Registry and Repository (LFRR) in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The controls for the External cohort of the previous GWAS used for to further increase statistical power were acquired from a database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGAP) University of Michigan study (n = 8580) [3]. In the CCHMC and CoFAR cohorts, 73% and 62% of subjects with EoE were male, respectively, and subjects with EoE had an age range of 2–52 years. The external control cohort was also used in an Immunochip analysis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), and none of these subjects had an SLE diagnosis [25].

Population stratification

Population stratification was performed, as previously described [3]. Ancestry informative markers were used to infer the top six principal components of genetic variation and correct for possible population stratification using Eigensoft. All local cases and controls were self-identified as having European ancestry, and principal component analysis was used to exclude subjects (n = 376) who segregated >4 standard deviations outside of the mean of the first 5 principal components (Supplemental Fig. 3). After outlier removal, there were no significant differences in the first four principal components (p < 0.1).

Genotyping quality control

Quality control on the variants from autosomal chromosomes was performed, as previously described [3]. Variants were assessed in this study if they met the following criteria: minor allele frequency greater than 1% and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the controls (P < 10-4). We controlled for the presence of potential batch effects by removal of SNPs that exhibited outlier fluorescence associated with deviation between plates (P < 10−4), as per the manufacturer’s recommendation. The final genotyping rate for all SNPs was 96.3%. After applying the above filters, genotypes from 79,405 autosomal SNPs in 1210 subjects with EoE and 3734 subjects without EoE were used in the final analyses (Supplemental Table 1).

Genetic association analysis and imputation to the 1000 genomes reference panel

Association analyses were performed in PLINKv1.9 and SNPTESTv2.5.2 [90]. To detect associated variants that were not directly genotyped, highly associated regions were imputed with IMPUTE2 and used a composite imputation reference panel of integrated haplotypes from the 1000 Genomes Project sequence data freezes from August 2012 [91, 92]. Imputed genotypes were required to meet or exceed a probability threshold of 0.9, an information measure of >0.5, and the same quality-control criteria threshold described for the genotyped non-autosomal markers. Genome-wide significance was set at p values ≤5 × 10-8.

RNA sequencing

Esophageal biopsy RNA was isolated from subjects with active EoE disease and unaffected controls and RNA from EPC2 esophageal epithelial cells grown in an air–liquid interface, as previously described [3, 22, 93]. RNA sequencing acquiring 50 million mappable 125 base-pair reads from paired-end libraries was performed at the Genetic Variation and Gene Discovery Core Facility at CCHMC. Data were aligned to the GrCh37 build of the human genome using the Ensembl [94] annotations as a guide for TopHat [95]. Expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 in BioWardrobe [96, 97]. The expression studies were well powered to identify 2-fold differences in gene expression (β = 1.0 for 2-fold changes with α of 0.05 and variance of 30% in biopsy data (Fig. 3a) and 10% variance in the in vitro cell line data (Fig. 2b). Datasets are deposited in NCBI GEO: GDS3223 and GSE58640.

References

Kottyan LC, Rothenberg ME. Genetics of eosinophilic esophagitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:580–8.

Alexander ES, Martin LJ, Collins MH, Kottyan LC, Sucharew H, He H, et al. Twin and family studies reveal strong environmental and weaker genetic cues explaining heritability of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1084–92 e1.

Kottyan LC, Davis BP, Sherrill JD, Liu K, Rochman M, Kaufman K, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of eosinophilic esophagitis provides insight into the tissue specificity of this allergic disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:895–900.

Sleiman PM, Wang ML, Cianferoni A, Aceves S, Gonsalves N, Nadeau K, et al. GWAS identifies four novel eosinophilic esophagitis loci. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5593.

Litosh VA, Rochman M, Rymer JK, Porollo A, Kottyan LC, Rothenberg ME. Calpain-14 and its association with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1762–71 e7.

Sherrill JD, Rothenberg ME. Genetic and epigenetic underpinnings of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:269–80.

Greisenegger EK, Zimprich F, Zimprich A, Gleiss A, Kopp T. Association of the chromosome 11q13.5 variant with atopic dermatitis in Austrian patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:142–5.

Tang XF, Tang HY, Sun LD, Xiao FL, Zhang Z, Li Y, et al. Genetic variant rs4982958 at 14q11.2 is associated with allergic rhinitis in a Chinese Han population running title: 14q11.2 is a susceptibility locus for allergic rhinitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22:55–62.

Ferreira MA, Matheson MC, Duffy DL, Marks GB, Hui J, Le Souef P, et al. Identification of IL6R and chromosome 11q13.5 as risk loci for asthma. Lancet. 2011;378:1006–14.

Li J, Zhang Y, Zhang L. Discovering susceptibility genes for allergic rhinitis and allergy using a genome-wide association study strategy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:33–40.

Ferreira MA, Matheson MC, Tang CS, Granell R, Ang W, Hui J, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 11 risk variants associated with the asthma with hay fever phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1564–71.

Weidinger S, Willis-Owen SA, Kamatani Y, Baurecht H, Morar N, Liang L, et al. A genome-wide association study of atopic dermatitis identifies loci with overlapping effects on asthma and psoriasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4841–56.

Ramasamy A, Curjuric I, Coin LJ, Kumar A, McArdle WL, Imboden M, et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis of genetic variants associated with allergic rhinitis and grass sensitization and their interaction with birth order. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:996–1005.

Hinds DA, McMahon G, Kiefer AK, Do CB, Eriksson N, Evans DM, et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis of self-reported allergy identifies shared and allergy-specific susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2013;45:907–11.

Patel ZH, Kottyan LC, Lazaro S, Williams MS, Ledbetter DH, Tromp H, et al. The struggle to find reliable results in exome sequencing data: filtering out Mendelian errors. Front Genet. 2014;5:16.

Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, Annaiah K, Martin LJ, Cianferoni A, et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:289–91.

Marenholz I, Esparza-Gordillo J, Ruschendorf F, Bauerfeind A, Strachan DP, Spycher BD, et al. Meta-analysis identifies seven susceptibility loci involved in the atopic march. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8804.

O’Regan GM, Campbell LE, Cordell HJ, Irvine AD, McLean WH, Brown SJ. Chromosome 11q13.5 variant associated with childhood eczema: an effect supplementary to filaggrin mutations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:170–4 e1-2.

Poninska JK, Samolinski B, Tomaszewska A, Raciborski F, Samel-Kowalik P, Walkiewicz A, et al. Haplotype dependent association ofrs7927894 (11q13.5) with atopic dermatitis and chronic allergic rhinitis: a study in ECAP cohort. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0183922.

Li X, Ampleford EJ, Howard TD, Moore WC, Li H, Busse WW, et al. The C11orf30-LRRC32 region is associated with total serum IgE levels in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:575–8. 578 e1-9

Yang SK, Hong M, Zhao W, Jung Y, Baek J, Tayebi N, et al. Genome-wide association study of Crohn’s disease in Koreans revealed three new susceptibility loci and common attributes of genetic susceptibility across ethnic populations. Gut. 2014;63:80–7.

Namjou B, Marsolo K, Caroll RJ, Denny JC, Ritchie MD, Verma SS, et al. Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) in EMR-linked pediatric cohorts, genetically links PLCL1 to speech language development and IL5-IL13 to Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Front Genet. 2014;5:401.

Cortes A, Brown MA. Promise and pitfalls of the Immunochip. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:101.

Alberts R, de Vries EMG, Goode EC, Jiang X, Sampaziotis F, Rombouts K et al. Genetic association analysis identifies variants associated with disease progression in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 2017 https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313598 [Epub ahead of print].

Langefeld CD, Ainsworth HC, Cunninghame Graham DS, Kelly JA, Comeau ME, Marion MC, et al. Transancestral mapping and genetic load in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Commun. 2017;8:16021.

Takeuchi M, Mizuki N, Meguro A, Ombrello MJ, Kirino Y, Satorius C, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related loci implicates host responses to microbial exposure in Behcet’s disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2017;49:438–43.

Zhao J, Ma J, Deng Y, Kelly JA, Kim K, Bang SY, et al. A missense variant in NCF1 is associated with susceptibility to multiple autoimmune diseases. Nat Genet. 2017;49:433–7.

Gutierrez-Achury J, Zorro MM, Ricano-Ponce I, Zhernakova DV, Coeliac Disease Immunochip Consortium RC, Diogo D, et al. Functional implications of disease-specific variants in loci jointly associated with coeliac disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:180–90.

Westerlind H, Mellander MR, Bresso F, Munch A, Bonfiglio F, Assadi G, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related loci identifies HLA variants associated with increased risk of collagenous colitis. Gut. 2017;66:421–8.

Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, Ng SC, Alberts R, Takahashi A, et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015;47:979–86.

Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Ellinghaus E, Stuart PE, Capon F, Knight J, et al. Enhanced meta-analysis and replication studies identify five new psoriasis susceptibility loci. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7001.

Li J, Jorgensen SF, Maggadottir SM, Bakay M, Warnatz K, Glessner J, et al. Association of CLEC16A with human common variable immunodeficiency disorder and role in murine B cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6804.

Onengut-Gumuscu S, Chen WM, Burren O, Cooper NJ, Quinlan AR, Mychaleckyj JC, et al. Fine mapping of type 1 diabetes susceptibility loci and evidence for colocalization of causal variants with lymphoid gene enhancers. Nat Genet. 2015;47:381–6.

Betz RC, Petukhova L, Ripke S, Huang H, Menelaou A, Redler S, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis in alopecia areata resolves HLA associations and reveals two new susceptibility loci. Nat Commun. 2015;6:5966.

Kumar V, Cheng SC, Johnson MD, Smeekens SP, Wojtowicz A, Giamarellos-Bourboulis E, et al. Immunochip SNP array identifies novel genetic variants conferring susceptibility to candidaemia. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4675.

International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics C, Beecham AH, Patsopoulos NA, Xifara DK, Davis MF, Kemppinen A, et al. Analysis of immune-related loci identifies 48 new susceptibility variants for multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1353–60.

International Genetics of Ankylosing Spondylitis C, Cortes A, Hadler J, Pointon JP, Robinson PC, Karaderi T, et al. Identification of multiple risk variants for ankylosing spondylitis through high-density genotyping of immune-related loci. Nat Genet. 2013;45:730–8.

Ellinghaus D, Baurecht H, Esparza-Gordillo J, Rodriguez E, Matanovic A, Marenholz I, et al. High-density genotyping study identifies four new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:808–12.

Liu JZ, Hov JR, Folseraas T, Ellinghaus E, Rushbrook SM, Doncheva NT, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies nine new risk loci for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:670–5.

Hinks A, Cobb J, Marion MC, Prahalad S, Sudman M, Bowes J, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies 14 new susceptibility loci for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:664–9.

Dubois PC, Trynka G, Franke L, Hunt KA, Romanos J, Curtotti A, et al. Multiple common variants for celiac disease influencing immune gene expression. Nat Genet. 2010;42:295–302.

Barrett JC, Clayton DG, Concannon P, Akolkar B, Cooper JD, Erlich HA, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2009;41:703–7.

Todd JA, Walker NM, Cooper JD, Smyth DJ, Downes K, Plagnol V, et al. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:857–64.

Liu JZ, Almarri MA, Gaffney DJ, Mells GF, Jostins L, Cordell HJ, et al. Dense fine-mapping study identifies new susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1137–41.

Liu X, Invernizzi P, Lu Y, Kosoy R, Lu Y, Bianchi I, et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses identify three loci associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:658–60.

Bentham J, Morris DL, Graham DSC, Pinder CL, Tombleson P, Behrens TW, et al. Genetic association analyses implicate aberrant regulation of innate and adaptive immunity genes in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1457–64.

Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Knight J, Ellinghaus E, Stuart PE, Capon F, et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1341–8.

Bradfield JP, Qu HQ, Wang K, Zhang H, Sleiman PM, Kim CE, et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis of six type 1 diabetes cohorts identifies multiple associated loci. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002293.

International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics C, Wellcome Trust Case Control C, Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CC, et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476:214–9.

Carithers LJ, Moore HM. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project. Biopreserv Biobank. 2015;13:307–8.

GTEx Consortium. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–60.

Keen JC, Moore HM. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project: linking clinical data with molecular analysis to advance personalized medicine. J Pers Med. 2015;5:22–9.

Moore HM. Acquisition of normal tissues for the GTEx program. Biopreserv Biobank. 2013;11:75–6.

Heng TS, Painter MW, Immunological Genome Project Consortium. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1091–4.

Wu C, Orozco C, Boyer J, Leglise M, Goodale J, Batalov S, et al. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R130.

Zeller T, Wild P, Szymczak S, Rotival M, Schillert A, Castagne R, et al. Genetics and beyond--the transcriptome of human monocytes and disease susceptibility. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10693.

Innocenti F, Cooper GM, Stanaway IB, Gamazon ER, Smith JD, Mirkov S, et al. Identification, replication, and functional fine-mapping of expression quantitative trait loci in primary human liver tissue. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002078.

Martin JE, Assassi S, Diaz-Gallo LM, Broen JC, Simeon CP, Castellvi I, et al. A systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus pan-meta-GWAS reveals new shared susceptibility loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4021–9.

Orozco G, Eyre S, Hinks A, Bowes J, Morgan AW, Wilson AG, et al. Study of the common genetic background for rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:463–8.

Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Sun X, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1228–33.

Johansson A, Marroni F, Hayward C, Franklin CS, Kirichenko AV, Jonasson I, et al. Common variants in the JAZF1 gene associated with height identified by linkage and genome-wide association analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:373–80.

Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, Voight BF, Marchini JL, Hu T, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–45.

Nakajima T, Fujino S, Nakanishi G, Kim YS, Jetten AM. TIP27: a novel repressor of the nuclear orphan receptor TAK1/TR4. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4194–204.

Kallionpaa H, Elo LL, Laajala E, Mykkanen J, Ricano-Ponce I, Vaarma M, et al. Innate immune activity is detected prior to seroconversion in children with HLA-conferred type 1 diabetes susceptibility. Diabetes. 2014;63:2402–14.

Bowes J, Budu-Aggrey A, Huffmeier U, Uebe S, Steel K, Hebert HL, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related susceptibility loci reveals new insights into the genetics of psoriatic arthritis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6046.

Miyadera H, Tokunaga K. Associations of human leukocyte antigens with autoimmune diseases: challenges in identifying the mechanism. J Hum Genet. 2015;60:697–702.

Parkes M, Cortes A, van Heel DA, Brown MA. Genetic insights into common pathways and complex relationships among immune-mediated diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:661–73.

Cleynen I, Boucher G, Jostins L, Schumm LP, Zeissig S, Ahmad T, et al. Inherited determinants of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis phenotypes: a genetic association study. Lancet. 2016;387:156–67.

Goyette P, Boucher G, Mallon D, Ellinghaus E, Jostins L, Huang H, et al. High-density mapping of the MHC identifies a shared role for HLA-DRB1*01:03 in inflammatory bowel diseases and heterozygous advantage in ulcerative colitis. Nat Genet. 2015;47:172–9.

Asano K, Matsushita T, Umeno J, Hosono N, Takahashi A, Kawaguchi T, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies three new susceptibility loci for ulcerative colitis in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1325–9.

Sollid LM. The roles of MHC class II genes and post-translational modification in celiac disease. Immunogenetics. 2017;69:605–16.

Nguyen TB, Jayaraman P, Bergseng E, Madhusudhan MS, Kim CY, Sollid LM. Unraveling the structural basis for the unusually rich association of human leukocyte antigen DQ2.5 with class-II-associated invariant chain peptides. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:9218–28.

Gutierrez-Achury J, Zhernakova A, Pulit SL, Trynka G, Hunt KA, Romanos J, et al. Fine mapping in the MHC region accounts for 18% additional genetic risk for celiac disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:577–8.

Johnson JB, Boynton KK, Peterson KA. Co-occurrence of eosinophilic esophagitis and potential/probable celiac disease in an adult cohort: a possible association with implications for clinical practice. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:977–82.

Dharmaraj R, Hagglund K, Lyons H. Eosinophilic esophagitis associated with celiac disease in children. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:263.

Jensen ET, Eluri S, Lebwohl B, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Increased risk of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with active celiac disease on biopsy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1426–31.

Pellicano R, De Angelis C, Ribaldone DG, Fagoonee S, Astegiano M. 2013 update on celiac disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Nutrients. 2013;5:3329–36.

Stewart MJ, Shaffer E, Urbanski SJ, Beck PL, Storr MA. The association between celiac disease and eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:96.

Traherne JA, Horton R, Roberts AN, Miretti MM, Hurles ME, Stewart CA, et al. Genetic analysis of completely sequenced disease-associated MHC haplotypes identifies shuffling of segments in recent human history. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e9.

Zuvich RL, Bush WS, McCauley JL, Beecham AH, De Jager PL, International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics C, et al. Interrogating the complex role of chromosome 16p13.13 in multiple sclerosis susceptibility: independent genetic signals in the CIITA-CLEC16A-SOCS1 gene complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3517–24.

Howson JM, Rosinger S, Smyth DJ, Boehm BO, Group A-ES, Todd JA. Genetic analysis of adult-onset autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:2645–53.

Tam RC, Li MW, Gao YP, Pang YT, Yan S, Ge W, et al. Human CLEC16A regulates autophagy through modulating mTOR activity. Exp Cell Res. 2017;352:304–12.

Edgar AJ, Birks EJ, Yacoub MH, Polak JM. Cloning of dexamethasone-induced transcript: a novel glucocorticoid-induced gene that is upregulated in emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:119–24.

Davison LJ, Wallace C, Cooper JD, Cope NF, Wilson NK, Smyth DJ, et al. Long-range DNA looping and gene expression analyses identify DEXI as an autoimmune disease candidate gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:322–33.

Kottyan LC, Zoller EE, Bene J, Lu X, Kelly JA, Rupert AM, et al. The IRF5-TNPO3 association with systemic lupus erythematosus has two components that other autoimmune disorders variably share. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:582–96.

Beaulieu YB, Leon Machado JA, Ethier S, Gaudreau L, Steimle V. Degradation, promoter recruitment and transactivation mediated by the extreme N-terminus of MHC class II transactivator CIITA isoform III. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148753.

Bhat KP, Truax AD, Greer SF. Phosphorylation and ubiquitination of degron proximal residues are essential for class II transactivator (CIITA) transactivation and major histocompatibility class II expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25893–903.

LeibundGut-Landmann S, Waldburger JM, Krawczyk M, Otten LA, Suter T, Fontana A, et al. Mini-review: Specificity and expression of CIITA, the master regulator of MHC class II genes. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1513–25.

Prahalad S, Ryan MH, Shear ES, Thompson SD, Giannini EH, Glass DN. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: linkage to HLA demonstrated by allele sharing in affected sibpairs. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2335–8.

Wellcome Trust Case Control C. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–78.

Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–13.

Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Dermitzakis E, Schaffner SF, Yu F, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–8.

Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536–47.

Flicek P, Ahmed I, Amode MR, Barrell D, Beal K, Brent S, et al. Ensembl 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D48–55.

Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–11.

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550.

Barski A, Kartashov A. BioWardrobe: an integrated platform for analysis of epigenomics and transcriptomics data. Genome Biol. 2015;16:158.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R37 AI045898, R01 AI124355, R01 DK107502, P30 AR070549, R01 AI024717, U01 AI130830, U01 HG008666, K24DK100303); National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) UL1TR000165; the Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease (CURED); the Buckeye Foundation; the Sunshine Charitable Foundation and its supporters, Denise A. Bunning and David G. Bunning; the LaCache Fund for GI Allergic and Immunologic Diseases; the Department for Veterans Affairs, and the American Partnership of Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED). This research was supported in part by the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation and its Cincinnati Genomic Control Cohort. The CoFAR arm of the study was supported by US NIH grant U19 AI066738 from NIAID and NIDDK. The project was also supported by several grants from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the US NIH: UL1 TR001082 (National Jewish), UL1 TR- 000067 (Mount Sinai), UL1 TR-000039 (Arkansas), UL1 TR-000083 (University of North Carolina) and UL1 TR-000424 (Johns Hopkins). We thank Shawna Hottinger and Amy Lawton for their editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript. This study would not be possible without the CoFAR site investigators: Scott H. Sicherer, MD; Stacie M. Jones, MD; Tamara T. Perry, MD; Amy Scurlock, MD; Edwin Kim, MD; Evan Dellon, MD, MPH; A. Wesley Burks, MD; Glenn T. Furuta, MD (or David Fleischer, MD depending upon paper); Donald Y.M. Leung, MD, PhD; and Donald Stablein, PhD. Other people who contributed to this study include Jessica Gau, RN, PNP; Diane Ananos, RN; Kim Mudd, RN, BSN, MS; Thomas Fitzgerald, BS; Peggy Chandler, APN; Erin O’Brien, BS; Suzanne Carlisle, RN; Anne Hiegel, RN; Pam Steele, BSN; Jessica Gebhart, MSHS; Deanna Hamilton, RN; Wendy Moore MS; JoAnne Newton RN; Susan Leung, RN; Donna Brown; Marshall Plaut, MD; and Julian Poyser, MPA, MS, CRNP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MER is a consultant for NKT Therapeutics, Pulm One, Spoon Guru, Celgene, Shire, Astra Zeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis; has an equity interest in NKT Therapeutics, Pulm One, Spoon Guru and Immune Pharmaceuticals; and has royalties from reslizumab (Teva Pharmaceuticals). MER is an inventor of several patents, owned by Cincinnati Children’s. VM receives is a consultant and receives research funding from Shire. PP is part of the speaker’s bureau for AbbottNutrition and Nutricia. GTF is the co-founder of EnteroTrack, culsultant to Shire, and receives royalties from UpToDate.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, and provide a link to the Creative Commons license. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kottyan, L.C., Maddox, A., Braxton, J.R. et al. Genetic variants at the 16p13 locus confer risk for eosinophilic esophagitis. Genes Immun 20, 281–292 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41435-018-0034-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41435-018-0034-z

This article is cited by

-

Minimally Invasive Approaches to Diagnose and Monitor Eosinophilic GI Diseases

Current Allergy and Asthma Reports (2024)

-

A Comprehensive Global Population-Based Analysis on the Coexistence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2024)

-

Genetic and Molecular Contributors in Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Current Allergy and Asthma Reports (2023)