Abstract

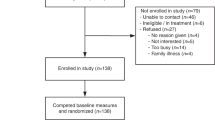

The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Consent and Disclosure Recommendation (CADRe) framework proposes that key components of informed consent for genetic testing can be covered with a targeted discussion for many conditions rather than a time-intensive traditional genetic counseling approach. We surveyed US genetics professionals (medical geneticists and genetic counselors) on their response to scenarios that proposed core informed consent concepts for clinical genetic testing developed in a prior expert consensus process. The anonymous online survey included responses to 3 (of 6 possible) different clinical scenarios that summarized the application of the core concepts. There was a binary (yes/no) question asking respondents whether they agreed the scenarios included the minimum necessary and critical educational concepts to allow an informed decision. Respondents then provided open-ended feedback on what concepts were missing or could be removed. At least one scenario was completed by 238 respondents. For all but one scenario, over 65% of respondents agreed that the identified concepts portrayed were sufficient for an informed decision; the exome scenario had the lowest agreement (58%). Qualitative analysis of the open-ended comments showed no consistently mentioned concepts to add or remove. The level of agreement with the example scenarios suggests that the minimum critical educational components for pre-test informed consent proposed in our prior work is a reasonable starting place for targeted pre-test discussions. This may be helpful in providing consistency to the clinical practice of both genetics and non-genetics providers, meeting patients’ informational needs, tailoring consent for psychosocial support, and in future guideline development.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and/or are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, MLGH.

References

Attard CA, Carmany EP, Trepanier AM. Genetic counselor workflow study: the times are they a-changin’? J Genet Couns. 2019;28:130–40.

Joseph G, Pasick RJ, Schillinger D, Luce J, Guerra C, Cheng JKY. Erratum to: information mismatch: cancer risk counseling with diverse underserved patients (J Genet Counsel, 10.1007/s10897-017-0089-4). J Genet Couns 2017;26:1105.

Hitchcock EC, Study C, Elliott AM. Shortened consent forms for genome-wide sequencing: parent and provider perspectives. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2020;8:e1254.

Hallquist MLG, Tricou EP, Ormond KE, Savatt JM, Coughlin CR 2nd, Faucett WA, et al. Application of a framework to guide genetic testing communication across clinical indications. Genome Med. 2021;13:71.

Robson ME, Bradbury AR, Arun B, Domchek SM, Ford JM, Hampel HL, et al. American society of clinical oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3660–7.

Committee Opinion No. 693. Counseling about genetic testing and communication of genetic test results. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e96–e101.

Dwarte T, Barlow-Stewart K, O’Shea R, Dinger ME, Terrill B. Role and practice evolution for genetic counseling in the genomic era: The experience of Australian and UK genetics practitioners. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:378–87.

Vears DF, Borry P, Savulescu J, Koplin JJ. Old challenges or new issues? genetic health professionals’ experiences obtaining informed consent in diagnostic genomic sequencing. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2021;12:12–23.

Bos W, Bunnik EM. Informed consent practices for exome sequencing: An interview study with clinical geneticists in the Netherlands. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2022;10:e1882.

Ormond KE, Borensztein MJ, Hallquist MLG, Ormond KE, Borensztein MJ, Hallquist MLG, et al. Defining the critical components of informed consent for genetic testing. J Personalized Med. 2021;11:1304.

Qualtrics software, Version Feb-March 2020 of Qualtrics. Copyright © 2020 Qualtrics. Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA.

Ormond KE, Hallquist MLG, Buchanan AH, Dondanville D, Cho MK, Smith M, et al. Developing a conceptual, reproducible, rubric-based approach to consent and result disclosure for genetic testing by clinicians with minimal genetics background. Genet Med. 2019;21:727–35.

IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Seaver LH, Khushf G, King NMP, Matalon DR, Sanghavi K, Vatta M, et al. Points to consider to avoid unfair discrimination and the misuse of genetic information: a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2021.11.002.

Unim B, Pitini E, Lagerberg T, Adamo G, De Vito C, Marzuillo C, et al. Current genetic service delivery models for the provision of genetic testing in Europe: a systematic review of the literature. Front Genet. 2019;10:552.

Bunnik EM, Dondorp WJ, Bredenoord AL, de Wert G, Cornel MC. Mainstreaming informed consent for genomic sequencing: a call for action. Eur J Cancer 2021;148:405–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.02.029.

Barnhart BJ, Reddy SG, Arnold GK. Remind me again: physician response to web surveys: the effect of email reminders across 11 opinion survey efforts at the American Board of Internal Medicine from 2017 to 2019. Eval Health Prof 2021;44:245–59.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Erin Ramos and Nicole Lockhart at NHGRI, and all the remaining members of the CADRe workgroup: Laura Hercher, Howard P. Levy, Julianne M. O’Daniel, Juliann M. Savatt, Melissa Stosic, and Hannah Wand. The work described was based on input from the CADRe working group, with additional members having contributed conceptually at various stages in the development of the rubrics, including: Kyle B. Brothers, Louanne Hudgins, Seema M. Jamal, Dave Kaufman, and Myra I. Roche. Finally, we are grateful to members of the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics writing seminar for comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers: U41HG009650 and U41HG009649. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: KEO, MJB, MLGH, AHB, WAF, HLP, MES, EPT, WRU, KEW, CRC. Data Curation: MLGH, KEO, MJB; Formal Analysis: MLGH, MJB, KEO; Funding Acquisition: KEO, AHB, WAF; Investigation: KEO, MJB.; Methodology: KEO, MJB, MLGH, AHB, WAF, HLP, MES, EPT, WRU, KEW, CRC; Project administration: MJB. Supervision: KEO, MLGH, AHB, CRC; Visualization: KEO, MJB, MLGH. Writing—original draft: MJB, MLGH, KEO; Writing—review and editing: KEO, MJB, MLGH, AHB, WAF, HLP, MES, EPT, WRU, KEW, CRC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AHB has received compensation as a section editor for the Journal of Genetic Counseling and holds an equity stake in MeTree and You, Inc. WRU receives book royalties from Wiley-Blackwell. MES has received compensation as a section editor for the Journal of Genetic Counseling. Remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Stanford IRB reviewed this study as exempt, and all aspects adhered to the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants reviewed an informed consent document before choosing to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hallquist, M.L.G., Borensztein, M.J., Coughlin, C.R. et al. Defining critical educational components of informed consent for genetic testing: views of US-based genetic counselors and medical geneticists. Eur J Hum Genet 31, 1165–1174 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-023-01401-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-023-01401-0

This article is cited by

-

Expanding what we know about rare genetic diseases

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

No need for options for choice for unsolicited findings in informed consent for clinical genetic testing

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)