Abstract

Background/objectives

Plant-based dietary patterns are becoming more popular worldwide. We aimed to examine the relationship between plant-based dietary patterns and the risk of inadequate or excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) in Iranian pregnant women.

Methods

We prospectively followed 657 pregnant women in Iran. Adherence to the plant-based diet, represented by plant-based (PDI), healthy (hPDI) and unhealthy plant-based (uPDI) dietary indexes was evaluated by applying a 90-item food frequency questionnaire during the first trimester of pregnancy. Multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional-hazards regression model was used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) across quartiles of plant-based diet scores.

Results

Over 25,562 person-weeks of follow-up, we documented 106 and 294 participants with inadequate and excessive GWG, respectively. We found a strong inverse association between adherence to the PDI and inadequate GWG after adjustment for demographic and confounding variables. Women in the highest quartile of the PDI had 50% lower risk of inadequate GWG than those in the lowest quartile (adjusted HR: 0.50; 95%CI 0.29, 0.89; P = 0.02). No significant association was found between hPDI and uPDI and inadequate GWG. There was no association between PDI, hPDI, and uPDI and the risk of excessive GWG.

Conclusions

Greater adherence to a plant-based diet during the first trimester of pregnancy may be associated with a lower risk of inadequate GWG. This finding needs to be confirmed in larger cohort studies, considering other pregnancy outcomes such as birth weight and the potential changes across the trimester in terms of food types and quantity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational weight gain (GWG), defined as the overall amount of weight obtained during pregnancy, is a complicated physiologic response to pregnancy, resulting from fetal development and gestational fat deposition [1]. GWG is a vital health marker during pregnancy and is associated with important maternal and infant health outcomes [2, 3]. According to the evidence, mothers with inadequate GWG are more prone to have infants with low birth weight and intrauterine growth retardation [4]. In contrast, mothers with excessive GWG are at a greater risk of preterm delivey and are more prone to have infants with increased birth weight and childhood obesity [5]. Moreover, mothers with excessive weight gain during pregnancy are at risk of greater maternal diseases including gestational diabetes and preeclampsia [6].

In 2018, 43% of Iranian pregnant women had excessive GWG, defined based on the Institute of Medicine recommendations [7]. Maternal diet is a prominent modifiable risk factor for inappropriate GWG [8, 9]. A recent systematic review exploring the association of dietary intake with GWG suggested that energy intake and macronutrient composition of the diet may be associated with the magnitude of weight gain during pregnancy [10]. Although the relation between single nutrients and GWG has been previously investigated, a more comprehensive dietary approach has emerged in nutritional epidemiology, which focuses on dietary pattern analysis. People consume nutrients and foods together, and hence, the dietary patterns might present a broader picture of an individual’s eating styles and might be a better predictor of health outcomes compared with single foods or nutrients [11].

It has been shown that plant-based and vegetarian dietary patterns are becoming more popular worldwide, particularly among women of reproductive age; however, little is known about the effect of these dietary patterns on pregnancy outcomes [12]. Although studies are limited and the information is inconsistent, childbearing mothers who adhered to a vegetarian diet had lower postpartum depression, cesarean delivery and maternal or neonatal mortality, probably due to receiving more fiber and lower fat and sugar [13,14,15,16].

Despite previous studies from Western countries examining the association of plant-based diets with GWG [17, 18], there has been no study to investigate this association in Middle-Eastern countries. Considering the increasing prevalence of obesity in women of reproductive age and the adverse health effect of inappropriate GWG on pregnancy outcomes, it seems that plant-based diets might be an appropriate eating style to reach adequate weight gain during pregnancy. In this regard, this prospective cohort study was conducted to examine the relation between plant-based dietary patterns during first trimester of pregnancy, represented by plant-based (PDI), healthy (hPDI) and unhealthy plant-based dietary indexes (uPDI), with the risk of inadequate or excessive GWG in Iranian pregnant women.

Materials and methods

Participants

This prospective cohort study was carried out within the framework of the Persian (Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in IRAN) Birth Cohort [19]. The Persian Birth Cohort is a prospective, ongoing cohort study carried out in five districts of Iran to provide scientific evidence and advance knowledge for developing evidence-based national policies on different aspects of developmental origins of health and diseases [19]. This cohort study explores the potential relation of environmental, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors with gestational outcomes and mother-child physical and cognitive well-being and health. For the present study, we used data from the Semnan branch of the Persian Birth Cohort. For inclusion in the present study, pregnant women living in Semnan, Iran, were recruited from health care centers between 2018 and 2020. Moreover, we used advertisements by medical clinics and local and social media across the city to motivate women to participate in this prospective study. Women were regarded as eligible for inclusion in the study if they lived in Semnan for at least 1 year, were during the first trimester of pregnancy, regardless of gravidity, congruity, or indication of fertility treatment, and aim to have a birth in one of the Semnan hospitals. Pregnancies ending in either natural vaginal delivery or cesarean section were eligible. Women who had twin gestations, hormonal diseases, or hormone therapy were excluded.

At first, 1024 women were qualified to participate in the present study. Of those, women who did not complete the dietary history questionnaire within the first trimester (n = 293), those with incomplete outcomes information or who did not stay until the end (n = 46), and women with energy intake <800 and >4200 kcal/d (n = 18), and those who were cigarettes smokers (n = 10) were additionally excluded from the study, leaving 657 mothers for final analyses.

All of the pregnant women were informed about the study procedures and all of them provided written informed consent before their inclusion in this study. The ethics committee of the Semnan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (Ethics code: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1400.213).

Assessment of dietary intake

Usual dietary intakes of the mothers during the first trimester of pregnancy were assessed by applying a 90-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) that was previously developed and validated for use in this prospective cohort study [19]. Data about dietary intakes were collected through face-to-face interviewing using a trained nutritionist. We asked participants to report their usual frequency of intake of food items listed in the FFQ, over their first trimester of pregnancy, based on commonly used units or portion sizes. The frequency of food consumption in each group was nine multiple-choice groups varying from “never or less than monthly” to “6 or more times every day” based on the nature of food items. All recorded consumption frequencies were converted to grams per day using household measures. We used Nutritionist IV software (version 7.0; N-Squared Computing, Salem, OR), revised for Iranian foods to measure the overall energy and nutrient intakes.

Calculation of plant-based dietary patterns

We generated PDI, hPDI, and uPDI scores as exposure in the present study [20, 21]. Based on the method introduced by Sajita et al. [21]. we created 18 food groups based on nutrient content within a larger group of healthy plant-based foods (whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, vegetable oils, tea/coffee), less healthy plant-based foods (fruit juices, refined grains, potatoes, sugar-sweetened beverages, sweets/desserts), and animal-based foods (animal fat, dairy, eggs, fish/seafood, meat, miscellaneous animal-based foods). We classified food groups into tertiles and assigned increasing or decreasing scores to each food group. With regards to increasing scores, participants in the highest tertile of a food group were given a score of 3, and those who were at the lowest tertile were assigned a score of 1. An inverse scoring system was used for decreasing scores.

To calculate PDI, healthy and less healthy plant-based food groups were given increasing scores, while animal-based food groups were given decreasing scores. For generating hPDI, increasing scores were given to healthy plant-based food groups and decreasing scores were given to both less healthy plant-based food groups and animal-based food groups. Finally, for calculating uPDI, increasing scores were given to less healthy plant-based food groups and decreasing scores were given to both healthy plant-based food groups and animal-based food groups. The scores of food groups were summed together to generate the indexes [20].

Outcome assessment

GWG was calculated by subtracting the mother’s weight during the first trimester (first weight) from the last weight before delivery. Weight was measured four times (first, second, and third trimesters and in the hospital before delivery) by trained staff with the same scales in the cohort center. According to the guidelines provided by the IOM, GWG was classified into three categories according to prepregnancy body mass index (BMI): inadequate, adequate and excessive [22]. Weight gain less than the following values was defined as inadequate GWG and weight gain above the following values was defined as excessive GWG; (1) Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2): 12.8–18 kg; (2) Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2): 11.5–16 kg; (3) Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2): 7–11.5 kg; and (4) Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2): 5–9 kg.

Assessment of other variables

Maternal demographic characteristics were collected by trained interviewers by applying structured pre-tested questionnaires that were designed for use in Persian Birth Cohorts [19]. Information on age, disease history, nausea during pregnancy, family income, level of education, prepregnancy BMI, pregnancy order, multivitamins usage and physical activity was collected by trained interviewers at recruitment. Physical activity levels were assessed by applying the validated International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [23]. The physical activity of participants was calculated based on Metabolic Equivalents minutes per week (MET-min/week) [24], and then, participants were classified into two categories including no or low physical activity (<3000 MET-min/week) and moderate and high low physical activity (>3000 MET-min/week). Trained interviewers assessed weight (to the nearest 0.5 kg) and height (to the nearest 0.5 cm) during the first, second, and third trimesters. Individuals wore light clothes and had no shoes when assessing their weight and height. Finally, the same protocol was used to evaluate maternal weight in the hospital before delivery. BMI was calculated as the ratio of weight (in kg) divided by the square of height (in m).

Statistical analyses

We calculated plant-based dietary indices and then categorized study participants according to quartiles of PDI, hPDI, and uPDI scores. The analysis of variance and Chi-square tests were applied, respectively, to compare continuous and categorical variables of the study participants across quartiles of PDI, hPDI and uPDI. We used Cox proportional-hazards model to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of inadequate and excessive GWG in relation to PDI, hPDI and uPDI scores. In the multivariable-adjusted models, we adjusted for age, university graduate (yes/no), occupation (full-time job, part-time job, no job with salary), income (<1 million, 1–3 million, 3–5 million, >5 million), physical activity (no or low/moderate to high), energy intake, prepregnancy supplement intake (yes/no), multivitamin use during pregnancy (yes/no), pre-pregnancy BMI, history of gestational diabetes mellitus (yes/no) and history of cardiovascular disease (yes/no). All analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., version 26). Statistical tests were two-sided and considered significant with P values <0.05.

Results

Overall, 657 pregnant women with a mean age of 28.8 ± 5.08 years were included. Demographic characteristics and dietary intake of the study participants across quartiles of PDI, hPDI, and uPDI scores are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The mean age of the participants across quartiles of indices ranged from 28.4–28.6 years in the bottom quartiles, to 28.5–29.2 years in the top quartiles of the PDI, hPDI and uPDI.

Compared with the individuals in the lowest quartile, individuals in the highest quartile of the PDI had a lower prepregnancy BMI and higher intake of energy, carbohydrate, total protein, total fat, dietary fiber, monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), vitamin C, magnesium, total grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts and lower intake of egg, dairy products, saturated fatty acids (SFA), and calcium (all P < 0.05). In terms of hPDI, individuals with highest score had a lower multivitamin use during pregnancy. Also, they had lower intake of energy, carbohydrate, total protein, total fat, SFA, MUFA, PUFA, magnesium, calcium, total grains, dairy, red and processed meats, poultry and egg, as well as higher intake of fruits than those with lowest score (all P < 0.05). Higher uPDI was related to higher percent of nausea during the current pregnancy. Individuals in the highest quartile of uPDI had lower intake of energy, carbohydrate, total protein, total fat, dietary fiber, SFA, MUFA, PUFA, vitamin C, magnesium, calcium, dairy, fruit, vegetable, legumes and nuts, red and processed meats, poultry and egg than those in the lowest quartile (all P < 0.05). Other demographic characteristics and dietary intakes were similar across quartiles of the PDI, hPDI, and uPDI scores.

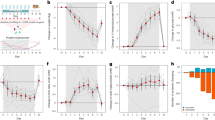

Table 3 presents crude and multivariable-adjusted HRs and 95%CIs of inadequate and excessive GWG across quartiles of the PDI, hPDI, and uPDI scores. Over 25,562 person-weeks of follow-up, we documented 106 and 294 participants with inadequate and excessive GWG, respectively. We found an inverse association between adherence to the PDI and inadequate GWG after adjustment for age, education, occupation, income, physical activity, energy and alcohol intake, prepregnancy supplement intake, multivitamin use during pregnancy, prepregnancy BMI, history of gestational diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Women in highest quartile of the PDI had 50% lower risk of inadequate GWG than those in the lowest quartile (adjusted HR 0.50; 95%CI 0.29, 0.89; P = 0.02). No significant association was found between hPDI and uPDI and inadequate GWG. There was no association between PDI, hPDI, and uPDI and the risk of excessive GWG (all P > 0.05; Table 3).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we examined the relationship between adherence to plant-based dietary patterns during the first trimester of pregnancy and risks of inadequate or excessive GWG in a small sample of pregnant women in a Middle-Eastern country. We found an inverse association between PDI and inadequate GWG after adjustment for potential confounders. However, we failed to find any significant association between hPDI and uPDI and inadequate GWG. There was no evidence of a relation between PDI, hPDI and uPDI with excessive GWG.

The American Dietetic Association position for childbearing women suggested the use of a healthy dietary pattern, rich in legumes, fish, fruits, vegetables and vegetable oils, combined with physical activity, to avoid inadequate or excessive GWG [25]. Our preliminary results confirmed that recommendation and indicated that greater adherence to the PDI during first trimester of pregnancy may be associated with a lower risk of inadequate GWG. However, possibly due to the small sample size, we did not find any association between uPDI and hPDI and risks of inadequate or excessive GWG.

A systematic review of 12 observational studies indicated that adherence to a vegetarian diet was inversely associated with excessive GWG and in contrast, greater adherence to dietary patterns rich in animal fats, proteins and energy-dense foods was associated with a higher risk [26]. In a cohort study of 1388 pregnant women in the US, adherence to a vegetarian diet in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy was related to a lower risk of excessive GWG [27]. In a retrospective web-based study of 1419 pregnant women, Kesary et al. indicated that different forms of plant-based diets were inversely related to excessive GWG, but were also associated with a higher risk of lower birth weight and small for gestational age [28]. In a Spanish retrospective study of 503 pregnant women, Cano-Ibáñez et al. indicated that greater compliance with the Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables, nuts, legumes, whole cereals and olive oil during different stages of pregnancy was related to a lower weight gain during pregnancy [29].

A systematic review of nine observational and experimental studies showed that pregnant mothers with vegetarian or vegan dietary patterns were more likely to have higher diet quality scores, as assessed bt Healthy Eating Index 2010, than their nonvegetarian counterparts [30]. A cross-sectional study among Brazilian vegetarian population showed an improved diet quality including adequate daily intake of fruits and vegetables and lower soft drinks consumption, as well as higher intake of natural foods and a lower intake of processed foods [31]. The abovementioned studies suggest that higher adherence to the PDI may be associated with a higher diet quality and thus, can explain our findings regarding the inverse association between adherence to the PDI and lower risk of inadequate GWG.

Current evidence indicated that people living in Middle-Eastern countries had a higher intake of refined grains and a lower intake of legumes, fruits, vegetables, dairy products and whole grains than those of Western countries [31,32,33,34,35]. For instance, previous studies showed that intake of fruits and vegetables among Iranian adults (on overage: 2.58 servings per day) was lower than the current recommendations by the World Health Organization (5 servings/d) [36]. Therefore, more efforts is needed in Iran to increase the adherence to plant-based diets among adluts.

Despite the current recommendation by the American Dietetic Association that promotes a well-balanced plant-based diet as a safe dietary pattern for all stages of life and in every physiological condition [37, 38], some studies have proposed that adherence to the vegetarian diets may be associated with considerable nutritional challenges, especially during pregnancy [39]. It is proposed that adherence to these diets may increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies, including inadequate supply of vitamin B12 and D, iron, calcium, zinc, iodine, proteins, and essential fatty acids [40]. Therefore, pregnant women require to have vigorous awareness about the overall quality of their diet to obtain all of the essential nutrients. Since we did not evaluate the association between adherence to plant-based diets and other pregnancy outcomes such as birth weight, more research is required to investigate the potential health outcomes of plant-based diets during pregnancy.

Our analysis showed a higher energy intake in the fourth quartile of uPDI as compared to the first quartile. Indeed, the foods considered in the uPDI groups include fruit juices, refined grains, potatoes, sugar-sweetened beverages, sweets/desserts, are high calorie food sources. The lower intake of energy at the highest category of uPDI may be due to lower intake of fruits, grains, and animal-based food groups that resulted in a lower energy intake. Indeed, Iranian traditional diet is a high carbohydrate diet and thus, the lower energy intake in the highest category of uPDI may be partly due to lower carbohydrate intake. This finding was consistent with that reported in another observational study in Iran, indicating lower energy intake in the highest category of uPDI [41].

The plausible biological mechanism for the relation between plant-based dietary patterns and the risk of inappropriate GWG might be due to a higher intake of fiber that is present in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and nuts [20, 42]. Dietary fiber influences weight regulation by improving the release of satiety hormones and subsequent contributing to reduced hunger [43] and decreasing the glucose response and postprandial insulin, that in turn, induces lipolysis and fat oxidation over lipid storage [44]. Furthermore, these effects might be incorporated into the prebiotic effects of fiber to alter the gut microbiota [45] and gastrointestinal actions, including gastric emptying, transition time of the intestine and colon and permeability of the intestine [46].

The strengths of the study include adjustments for a wide range of covariates in the analyses and being the first prospective cohort study in the Middle East area. We also gathered a substantial amount of information using a standard protocol and valid and reliable tools that decreases information bias related to food intakes, demographic characteristics and lifestyle-related behaviors. However, there are some limitations that deserve consideration. First, using FFQ to assess dietary intake might lead to misclassification of dietary intakes. Second, although we adjusted for a wide range of potential covariates, the likelihood of residual confounding should not be ignored. Third, we included a relatively small number of participants and thus, more large-scale cohort studies are needed to confirm the findings. Fourth, we evaluated the dietary intake during the first trimester and thus, the association between adherence to the plant-based diets during the second and third trimesters with GWG should be investigated in future research. Since, pregnancy is a dynamic physiological state, the dietary patterns could largely change across the trimester in terms of food types and quantity. Often nutrition counseling also plays a role to change the dietary habits. Therefore, it was critical to consider the temporal shift in the dietary intakes in future research.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that greater adherence to the plant-based diets during the first trimester of pregnancy may be associated with a lower risk of inadequate GWG. Further large-scale cohort studies are required to confirm our findings about the association of plant-based dietary patterns with GWG, considering the potential changes across the trimester in terms of food types and quantity and other pregnancy outcomes such as birth weight.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Herring SJ, Rose MZ, Skouteris H, Oken E. Optimizing weight gain in pregnancy to prevent obesity in women and children. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:195–203.

Dietz PM, Callaghan WM, Cogswell ME, Morrow B, Ferre C, Schieve LA. Combined effects of prepregnancy body mass index and weight gain during pregnancy on the risk of preterm delivery. Epidemiology. 2006;17:170–7.

Li C, Liu Y, Zhang W. Joint and independent associations of gestational weight gain and pre-pregnancy body mass index with outcomes of pregnancy in Chinese women: a retrospective cohort study. PloS One. 2015;10:e0136850.

Guan P, Tang F, Sun G, Ren W. Effect of maternal weight gain according to the Institute of Medicine recommendations on pregnancy outcomes in a Chinese population. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:4397–412.

Su W-j, Chen Y-l, Huang P-y, Shi X-l, Yan F-f, Chen Z, et al. Effects of prepregnancy body mass index, weight gain, and gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study in Xiamen, China, 2011–2018. Ann Nutr Metab. 2019;75:31–38.

Pregnancy as a window to future health: Excessive gestational weight gain and obesity. Semin Perinatol. Elsevier, 2015.

Hoorsan H, Majd HA, Chaichian S, Mehdizadehkashi A, Hoorsan R, Akhlaqghdoust M, et al. Maternal anthropometric characteristics and adverse pregnancy outcomes in iranian women: a confirmation analysis. Arch Iran Med. 2018;21:61–66.

Lagiou P, Tamimi R, Mucci L, Adami H, Hsieh C, Trichopoulos D. Diet during pregnancy in relation to maternal weight gain and birth size. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:231–7.

Reyes NR, Klotz AA, Herring SJ. A qualitative study of motivators and barriers to healthy eating in pregnancy for low-income, overweight, African-American mothers. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:1175–81.

Tielemans MJ, Garcia AH, Peralta Santos A, Bramer WM, Luksa N, Luvizotto MJ, et al. Macronutrient composition and gestational weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;103:83–99.

Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:3–9.

Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: vegetarian diets. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:1970–80.

Gaskin IM. Spiritual midwifery, Book Publishing Company, 2010.

Carter JP, Furman T, Hutcheson HR. Preeclampsia and reproductive performance in a community of vegans. South Med J. 1987;80:692–7.

Zhang C, Liu S, Solomon CG, Hu FB. Dietary fiber intake, dietary glycemic load, and the risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2223–30.

Frederick IO, Williams MA, Dashow E, Kestin M, Zhang C, Leisenring WM. Dietary fiber, potassium, magnesium and calcium in relation to the risk of preeclampsia. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:332–44.

Pistollato F, Sumalla Cano S, Elio I, et al. Plant-based and plant-rich diet patterns during gestation: beneficial effects and possible shortcomings. Adv Nut. 2015;6:581–91.

Zulyniak MA, de Souza RJ, Shaikh M, Desai D, Lefebvre DL, Gupta M, et al. Does the impact of a plant-based diet during pregnancy on birth weight differ by ethnicity? A dietary pattern analysis from a prospective Canadian birth cohort alliance. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017753.

Zare Sakhvidi MJ, Danaei N, Dadvand P, Mehrparvar AH, Heidari-Beni M, Nouripour S, et al. The prospective epidemiological research studies in IrAN (PERSIAN) birth cohort protocol: Rationale, design and methodology. Longitud Life Course Stud. 2021;12:241–62.

Martínez-González MA, Sánchez-Tainta A, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, Ros E, Arós F, et al. A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:320s–328s.

Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Chiuve SE, Borgi L, et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002039.

Medicine Io, Status IoMSoN, Pregnancy WGd, Pregnancy CoNSD, Lactation, Intake IoMSoD et al. Nutrition during pregnancy: Part I: weight gain, Part II: nutrient supplements, National Academy Press, 1990.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR, Tudor-Locke C, et al. 2011 Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–81.

Kaiser L, Allen LH. American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition and lifestyle for a healthy pregnancy outcome. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:553–61.

Streuling I, Beyerlein A, Rosenfeld E, Schukat B, von Kries R. Weight gain and dietary intake during pregnancy in industrialized countries–a systematic review of observational studies. J Perinat Med. 2011;39:123–9.

Stuebe AM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Associations of diet and physical activity during pregnancy with risk for excessive gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:58.e51–58.e588.

Kesary Y, Avital K, Hiersch L. Maternal plant-based diet during gestation and pregnancy outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302:887–98.

Cano-Ibáñez N, Martínez-Galiano JM, Luque-Fernández MA, Martín-Peláez S, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Delgado-Rodríguez M. Maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and their association with gestational weight gain and nutrient adequacy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7908.

Parker HW, Vadiveloo MK. Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2019;77:144–60.

Hargreaves SM, Araújo WMC, Nakano EY, Zandonadi RP. Brazilian vegetarians diet quality markers and comparison with the general population: a nationwide cross-sectional study. PLOS One. 2020;15:e0232954.

Aminianfar A, Soltani S, Hajianfar H, Azadbakht L, Shahshahan Z, Esmaillzadeh A. The association between dietary glycemic index and load and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;170:108469.

Daneshzad E, Tehrani H, Bellissimo N, Azadbakht L. Dietary total antioxidant capacity and gestational diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:5471316–5471316.

De La Rosa VY, Hoover J, Du R, Jimenez EY, MacKenzie D, Team NS, et al. Diet quality among pregnant women in the Navajo Birth Cohort Study. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16:e12961–e12961.

Miller V, Yusuf S, Chow CK, Dehghan M, Corsi DJ, Lock K, et al. Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e695–703.

Esteghamati A, Noshad S, Nazeri A, Khalilzadeh O, Khalili M, Nakhjavani M. Patterns of fruit and vegetable consumption among Iranian adults: a SuRFNCD-2007 study. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:177–81.

Craig WJ, Mangels AR. Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1266–82.

McGuire S. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th Edition, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, January 2011. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:293–4.

Piccoli GB, Clari R, Vigotti FN, Leone F, Attini R, Cabiddu G, et al. Vegan–vegetarian diets in pregnancy: danger or panacea? A systematic narrative review. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;122:623–33.

Cullum-Dugan D, Pawlak R. Removed: position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: vegetarian diets. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:801–10.

Mousavi SM, Shayanfar M, Rigi S, Mohammad-Shirazi M, Sharifi G, Esmaillzadeh A. Adherence to plant-based dietary patterns in relation to glioma: a case–control study. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1–11.

Hull HR, Herman A, Gibbs H, Gajewski B, Krase K, Carlson SE, et al. The effect of high dietary fiber intake on gestational weight gain, fat accrual, and postpartum weight retention: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2020;20:319.

Turner TF, Nance LM, Strickland WD, Malcolm RJ, Pechon S, O’Neil PM. Dietary adherence and satisfaction with a bean-based high-fiber weight loss diet: a pilot study. Int Sch Res Not. 2013;2013:915415.

Paul HA, Bomhof MR, Vogel HJ, Reimer RA. Diet-induced changes in maternal gut microbiota and metabolomic profiles influence programming of offspring obesity risk in rats. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–14.

Cotillard A, Kennedy SP, Kong LC, Prifti E, Pons N, Le Chatelier E, et al. Dietary intervention impact on gut microbial gene richness. Nature. 2013;500:585–8.

Mokkala K, Röytiö H, Munukka E, Pietilä S, Ekblad U, Rönnemaa T, et al. Gut microbiota richness and composition and dietary intake of overweight pregnant women are related to serum zonulin concentration, a marker for intestinal permeability. J Nutr. 2016;146:1694–1700.

Funding

This study was supported by Semnan University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 1908).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AJ, SS-B, and MMK conceived and designed th study, SZM, HM and AE contributed to the data gathering, SZM and AJ analyzed the data, SZM, HM, AE, and AJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript, SS-B and MMK critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. SS-B had primary responsibility for final content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the ethics committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jayedi, A., Zeraattalab-Motlagh, S., Moosavi, H. et al. Association of plant-based dietary patterns in first trimester of pregnancy with gestational weight gain: results from a prospective birth cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr 77, 660–667 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-023-01275-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-023-01275-x