Abstract

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) is a housekeeping enzyme involved in the pentose phosphate shunt for producing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Severe G6PD deficiency leads to embryonic lethality, but the underlying mechanism is unclear. In the current study, the effects of G6PD on epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), especially during embryonic development, were investigated. The knockdown of G6PD induced morphological changes, accompanied by the suppression of epithelial markers, E-cadherin and β-catenin, in A549 and MDCK cells. Such modulation of EMT was corroborated by the enhancement of migration ability in G6PD-knockdown A549 cells. Zebrafish embryos with g6pd knockdown exhibited downregulation of the E-cadherin/β-catenin adhesion molecules and impaired embryonic development through reduction in epiboly rate and increase in cell shedding at the embryo surface. The dysregulation in zebrafish embryonic development caused by g6pd knockdown could be rescued through human G6PD or CDH1 (E-cadherin gene) cRNA coinjection. The Smad3/miR-200b axis was dysregulated upon G6PD knockdown, and the reconstitution of SMAD3 in G6PD-knockdown A549 cells restored the expression of E-cadherin/β-catenin. The inhibition of NADPH oxidase (NOX) activation through the loss of p22phox signaling was involved in the dysregulation of the Smad3/miR-200b axis upon G6PD knockdown. The reconstitution of G6PD led to the recovery of the regulation of NOX/Smad3/miR-200b signaling and increased the expression of E-cadherin/β-catenin in G6PD-knockdown cells. Thus, these results suggest that in the EMT process, G6PD plays an important regulatory role as an integral component of the NOX/Smad3/miR-200b axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) is a housekeeping enzyme with the major function of regenerating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) to maintain cellular redox homeostasis1,2,3,4. Because NADPH is essential for NADPH oxidase (NOX) and nitric oxide synthase to produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen species for signaling, many new cellular roles of G6PD have been identified. G6PD modulates xenobiotic metabolism via the Nrf2 signaling pathway and affects the xenobiotic metabolizing enzyme expression5. Moreover, it acts as a key regulator of the cellular inflammatory and immune response against viral infection6,7. Because G6PD is a rate-limiting enzyme in the pentose-phosphate shunt, it is essential for regulating energy consumption and glucose metabolism8. These studies have indicated that G6PD plays an important role in modulating many cellular functions.

Severe G6PD deficiency is embryonically lethal9,10. G6PD is essential in the regulation of embryonic development. Severe G6PD deficiency in mice causes the demise of male embryos in hemizygous G6PD deficiency and female embryos in heterozygous G6PD deficiency9. Reduced litter size is also observed in mice with slight G6PD deficiency11. The study of a severe G6PD deficiency mouse model delineates that the initial development of all embryos, especially in early gestation, is unimpaired9. In Caenorhabditis elegans, G6PD deficiency has a strong impact on egg hatching and embryonic development; this is attributed to altered lipid metabolism12. All these data indicate that G6PD is vital in embryonic development and differentiation. However, the underlying mechanism through which G6PD affects embryonic development has not fully been elucidated.

A possible mechanism for G6PD to modulate embryonic development could be mediated by its effect on epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT is a process in which cells transit between the epithelial and mesenchymal states and drives many important aspects of embryonic development13. It is characterized by the loss of epithelial surface markers, which occurs in response to EMT transcription factors or epigenetic regulators. Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is vital because of its abilities in the molecular regulation of EMT for the development of metazoans14,15. It is temporally expressed in the developing heart of mice16, and its subfamilies are the key regulators for the generation of axes during embryogenesis17. Data from the Gene Expression Omnibus database indicate that the gene expression of G6PD is downregulated in TGF-β-treated cells (accession nos. GDS3710, GDS2975, and GDS4106). This implies that G6PD may be a factor in regulating the EMT process. The relationship between the G6PD status and EMT process thus warrants investigation.

In the current study, G6PD was identified for the first time as a regulator of the EMT process during embryonic development, demonstrated by cell lines and zebrafish models. G6PD knockdown modulated the expression of EMT markers and zebrafish embryonic development. The modulation of EMT through G6PD knockdown is correlated with the impairment of NOX/Smad3/miR-200b signaling. These data suggest that G6PD plays an important role in regulating embryonic development, as an integral part of the NOX/Smad3/miR-200b axis for modulating the expression of adhesion molecules.

Results

EMT-associated morphological changes in G6PD-knockdown A549 and MDCK cells

To ascertain whether EMT progression is linked to G6PD expression, A549 cells treated with TGF-β were used as cell model. After TGF-β1 treatment for 24 h, a clear morphological change from epithelial (round shape) to mesenchymal (spindle shape) cell types (Fig. 1a) was observed in A549 cells, with E- to N-cadherin switching by decreasing E-cadherin and increasing N-cadherin expression (Fig. 1c). Meanwhile, a decrease in the transcriptional and translational levels of G6PD was detected through polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Western blot, and G6PD activity assays (Fig. 1b, c, and d). To assess whether the morphological differences were associated with cellular G6PD expression, we knocked down G6PD by using lentiviruses to deliver shRNA into two epithelial cell lines, namely A549 and MDCK cells. G6PD-knockdown efficiency was confirmed through protein expression and activity assay (Figs. 1e-f). Compared with the control A549-LS (Lentiviral Scramble control) cells, A549-LG (Lentiviral G6PD shRNA) cells expressed approximately 16% G6PD levels (Fig. 1e). MDCK-LG cells expressed 42% G6PD levels compared with the control MDCK-LS cells (Fig. 1f). G6PD-knockdown cells presented significant alteration in cellular morphology, and both A549-LG and MDCK-LG cells exhibited more mesenchymal-like morphology than did their control cells (Fig. 1g).

a TGF-β treatment induced morphological changes in A549 cells, accompanied by G6PD inhibition. A549 cells were serum starved for 24 h and treated with 5 ng/mL of TGF-β for 24 h. Compared with the control cells, A549 cells exhibited constricted and mesenchymal-like morphologies after TGF-β stimulation (5 ng/mL). Scale bar, 30 µm. One representative example is shown out of three experiments. b The transcript level of G6PD in TGF-β-treated A549 cells was analyzed through real-time PCR. The relative result was normalized to ACTB, calculated relative to that without the TGF-β treatment counterpart (set to 1 for one experiment), and presented as mean ± SD (**p < 0.01) by performing independently in triplicate. c Protein expressions of G6PD, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin in A549 cells with or without TGF-β stimulation were analyzed through Western blotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control. One representative example is shown out of three experiments. d G6PD activities were determined in A549 cells with or without TGF-β stimulation. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (**p < 0.01). e G6PD expressions and activities of G6PD-knockdown (LG) A549 and control (LS) cells were determined through Western blot and G6PD activity assay. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (**p < 0.01). One representative example is shown out of three western blot experiments. f G6PD expressions and activities of G6PD-knockdown (LG) MDCK and control (LS) cells were determined through Western blot and G6PD activity assay. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (*p < 0.05). One representative example is shown out of three Western blot experiments. g A549-LG and MDCK-LG cells exhibited constricted and mesenchymal-like morphologies compared with LS cells. Scale bar, 50 µm. One representative example is shown out of four experiments

Decreased expressions of E-cadherin and β-catenin through G6PD knockdown in A549 and MDCK cells

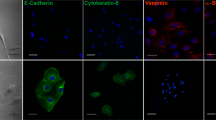

To further investigate the correlation between G6PD and EMT, the EMT-associated proteins were analyzed in G6PD-knockdown A549 and MDCK cells. The downregulation of E-cadherin and 8–10% upregulation of N-cadherin were observed in A549-LG and MDCK-LG cells (Fig. 2a). The expression of β-catenin, a subunit of the cadherin protein complex, was also decreased in A549-LG and MDCK-LG cells (Fig. 2a). Moreover, compared with the respective control cells, a reduction in E-cadherin and β-catenin expression and increase in N-cadherin expression at the cell surface were also observed in A549-LG and MDCK-LG cells examined through immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 2b). Using siRNA to further confirm our observation, the gene expression of CDH1 and CTNNB1 were downregulated upon G6PD knockdown concomitant with CDH2 and SNAI1 upregulation in A549 cells (Supplementary Figure 1). These results demonstrate that the inhibition of G6PD expression can reduce cell–cell adhesion through the dysregulation of the adhesion protein complex, which leads to the modulation of EMT.

a Compared with control (LS) cells, a significant decrease in the protein expressions of E-cadherin and β-catenin and an increase in N-cadherin expression in A549-LG and MDCK-LG cells were observed through Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as the loading control. One representative example is shown out of three experiments. b Immunofluorescence staining for E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and β-catenin (left, right, and central panels, respectively; green) was observed in A549-LG and MDCK-LG cells compared with in their control LS cells. Nuclei were stained with Hoechest 33342 (blue). Scale bar, 20 µm. One representative example is shown out of three experiments

Enhanced cell migration in G6PD-knockdown A549 cells

Because the downregulation of E-cadherin and β-catenin is often associated with increased cell migration, a scratch wound assay was performed for 24 h. G6PD knockdown was accompanied by enhanced cell migration by 31 ± 3.6% in A549-LG cells compared with A549-LS cells (Figs. 3a, b, p < 0.05; raw data in Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, to exclude the effect of proliferation caused by G6PD knockdown, we performed a transwell migration assay. Inhibiting G6PD expression increased migration over a membrane by 59 ± 3.7%, compared with the A549-LS group (Figs. 3c, d, p < 0.05). These enhanced migration data provide further support to the notion that G6PD knockdown can affect EMT.

a Wound-healing assay was performed to analyze the motility of A549-LS and -LG cells. After serum starvation for 24 h, cell mono-layers were wounded with a sterile 200-µL tip and washed with a serum-free medium. Cells were photographed at 0 h and incubated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 24 h. Images represent the results obtained from four independent experiments. b Quantification was performed by measuring the size of the wound at indicated time points. The size at 24 h was calculated relative to that at 0 h (set to 100%), and the graph shows the relative wound size in A549-LS cells and A549-LG cells (*p < 0.05). c In vitro migration assay was performed to analyze the motility of A549-LS and -LG cells. Cell mono-layers were seeded on Millicell® culture plate inserts (pore size, 8 μm; Millipore) in serum-free DMEM, and they migrated into the lower compartment containing DMEM with 10% FBS. The migrated cells were fixed, stained, and photographed at 24 h. Scale bar, 50 µm. Images represent the results obtained from five independent experiments. d Quantification was conducted by counting migrated cells in five different fields of each independent experiment, and the results are presented as mean ± SD (**p < 0.01)

Impaired embryonic development of zebrafish by g6pd knockdown

Because EMT plays an important role during embryonic development14,15, the effects of g6pd knockdown on early embryonic development were investigated in a zebrafish model. The optimal delivering dose of g6pd morpholino (MO) were determined following Lund’s group18. The kinetics of G6pd activity at 24, 48, and 72 h postfertilization (hpf) are shown in Supplementary Figure 2. The kinetic data of control MO revealed that G6pd activity was increased during zebrafish embryonic development (Supplementary Figure 2a). However, g6pd MO injection reduced G6pd activity (Supplementary Figure 2a). Compared with the control embryos at 72 hpf, the embryos injected with g6pd MO exhibited a decrease in G6pd activity (41% of control MO; p < 0.05; Fig. 4a) and the inhibition of E-cadherin and β-catenin expression (Fig. 4b). Moreover, the injection of human G6PD cRNA restored the G6pd activity and the expression of E-cadherin and β-catenin in the g6pd morphants (Figs. 4a, b). The expressions of EMT markers were also altered by the G6pd status in zebrafish embryos even at 6 and 16 hpf (Supplementary Figure 3). Decreased expression of β-catenin in g6pd MO embryos could be rescued through the coinjection of human G6PD cRNA but not CDH1 cRNA (Fig. 4b).

a Single-cell zebrafish embryos were injected with random MO, MOs targeting g6pd only, and MOs targeting g6pd with human G6PD or human CDH1 cRNA rescue. Whole-cell lysates were prepared at 72 hpf from embryo injection. G6pd activities were determined through the G6pd activity assay, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (*p < 0.05 compared with the control MO group). b Protein expressions of E-cadherin and β-catenin in the whole-embryo lysates at 72 hpf were analyzed through Western blot. β-Actin was used as the loading control. One representative Western blot example is shown out of three experiments. c Zebrafish embryos were injected with random MO, MOs targeting g6pd only, or MOs targeting g6pd with human G6PD or human CDH1 cRNA rescue and were monitored through microscopy. Gastrulation was initiated in the MO-injected embryos at 6 hpf. The epiboly rate was decreased in the g6pd MO-injected embryos (top panel). Scale bar, 250 μm. The phenotypic examination of g6pd MO at 16 hpf revealed shedding of the cells at the embryo surface (arrowhead in in the bottom panel). Rescue of the phenotype was performed by coinjecting g6pd MOs with human G6PD or human CDH1 cRNA. n, total number of embryos analyzed from three independent experiments. Scale bar, 250 μm

E-cadherin is involved in the regulation of zebrafish cell movement and tissue formation during early embryogenesis where loss of E-cadherin decreases epiboly rate and reduces cell–cell adhesion19. Additional phenotype experiments were performed to determine whether other EMT-related developmental defects could be observed in the g6pd-knockdown embryos. Indeed, the epiboly rate was decreased (Fig. 4c, up panel), and the change of cell shape at the embryo surface was also observed (Fig. 4c, bottom panel) in g6pd MO-injected embryos compared to control embryos at 6 and 16 hpf, respectively. The coinjection of g6pd MO with human G6PD or CDH1 cRNA rescued these developmental defects (Fig. 4c). All these data indicate that g6pd knockdown influenced the embryonic development of zebrafish through the dysregulation of E-cadherin and β-catenin expression, which led to defective EMT.

Downregulation of E-cadherin and β-catenin through G6PD knockdown via the inhibition of the Smad3/miR-200b pathway

Upon delineating the possible mechanism through which G6PD affects E-cadherin expression, Zeb1, a well-known transcription inhibitor of E-cadherin, was examined. The result showed Zeb1 was upregulated in A549-LG cells compared with in A549-LS cells (Fig. 5a, d). Further study of the miR-200 family, the regulatory miRNAs targeting ZEB1 and modulating the expression of β-catenin20, revealed that miR-200b was downregulated in A549-LG cells (Fig. 5b). Moreover, the transcriptional (Fig. 5c) and translational levels (Fig. 5d) of Smad3, the upstream regulator of miR-200b, were also downregulated in A549-LG cells. The reconstitution of SMAD3 in A549-LG cells increased endogenous miR-200b expression (Fig. 5e), downregulated Zeb1 expression, and upregulated the expressions of E-cadherin and β-catenin (Fig. 5f). These results indicate that G6PD knockdown functionally modulates EMT by inhibiting the Smad3/miR-200b pathway.

a The transcript level of ZEB1 was determined through real-time PCR, normalized to ACTB, and calculated relative to the LS group (set to 1). Results are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (*p < 0.05). b The transcript levels of miR-200b in A549-LS and -LG cells were validated through real-time PCR and normalized to RNU6. The expression level was calculated relative to LS (set to 1) and presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01). c The transcript level of SMAD3 was determined through real-time PCR, normalized to ACTB, and calculated relative to the LS group (set to 1). Results are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01). d Protein lysates collected from A549-LG and -LS cells were used to analyze the expressions of Zeb1 and Smad3. β-Actin was used as the loading control. One representative example is shown out of three experiments. e Ectopic Smad3 was expressed in SMAD3-overexpressing A549-LG cells, and the transcript levels of miR-200b were analyzed through real-time PCR, normalized to RNU6, and calculated relative to the vector control (set to 1). Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01). f The protein expressions of Smad3, E-cadherin, β-catenin, and Zeb1 were analyzed in SMAD3-overexpressing A549-LG cells. β-Actin was used as the loading control. One representative example is shown out of three experiments

Upstream mechanism for EMT modulation through G6PD knockdown due to NOX inhibition

Because NOX activation is the key regulator of the Smad3 pathway, the mechanism of the G6PD status in the Smad3 pathway was delineated by analyzing the expressions of NOXs in these cells. The mRNA expression levels of NOX1, NOX2, p22 phox , and p67 phox , the major NOX subunits in A549 cells, were downregulated in A549-LG cells (data not shown). Because p22phox is the common subunit of NOX1 and NOX2, we further analyzed the protein expression of p22phox in A549-LS and LG cells. As shown in Fig. 6a, the translational level of p22phox was downregulated in A549-LG cells compared with in A549-LS cells. Further study was performed by knocking down p22 phox in A549 cells, and decreased protein expressions of Smad3, E-cadherin, and β-catenin, along with upregulated Zeb1, were observed (Fig. 6b). The SNAI1 gene expression was upregulated by p22 phox knockdown (Supplementary Figure 4). The level of miR-200b was also downregulated in p22 phox -knockdown A549 cells (Fig. 6c), and increased migration over a membrane by 23 ± 5.7%, compared with the scramble control group (Fig. 6d, p < 0.05). These data indicate that the modulation of the EMT process through G6PD knockdown may partly occur due to the downregulation of the NOX/Smad3/miR-200b pathway.

a The protein level of p22phox was determined through Western blot analysis in A549-LS and LG cells. β-Actin was used as the loading control. One representative example is shown out of three experiments. b A549 cells were transducted with recombinant lentivirus for knocking down p22 phox . Ninety-six hours later, the cell lysate was harvested for analysis. The protein expressions of p22phox, Smad3, Zeb1, E-cadherin, and β-catenin were measured through Western blot. β-Actin was used as the loading control. One representative example is shown out of three experiments. c The level of miR-200b expression was determined in p22 phox -knockdown and control A549 cells through real-time PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05. d In vitro migration assay was performed to analyze the motility of p22 phox -knockdown and control A549 cells. Quantification was conducted by counting migrated cells in five different fields of each independent experiment, and the results are presented as mean ± SD (*p < 0.05)

Increased E-cadherin/β-catenin expression by G6PD reconstitution in A549-LG cells through NOX/Smad3/miR-200b signaling

We further reconstituted G6PD expression in A549-LG cells, using Δ1339 as the dominant negative control (1339G>A, classic I G6PD deficiency). The transfection of HTG6PD increased the G6PD activity in A549-LG cells, and the transfection of Δ1339 in A549-LG cells did not affect the G6PD activity (Fig. 7a). MiR-200b expression was highly correlated with G6PD activity (Fig. 7b), and G6PD reconstitution upregulated E-cadherin and β-catenin expression and increased the expression of Smad3 and p22phox (Fig. 7c). Moreover, E-cadherin expression could be downregulated by miR-200b LNA and upregulated by ZEB1 siRNA even in the presence of Δ1339 or HTG6PD A549-LG cells (Supplementary Figure 5). Together, these data provide novel information concerning the role of G6PD in modulating the EMT process through the NOX/Smad3/miR-200b pathway.

a Protein extracts (10 µg) of G6PD-reconstituted A549-LG (HTG6PD) and negative control (Δ1339) cells were used to determine G6PD activities. Results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01). b The transcript level of miR-200b was measured through real-time PCR, normalized to RNU6, and calculated relative to the Δ1339 group (set to 1). Results are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01). c The protein expressions of G6PD, E-cadherin, β-catenin, P22phox, and Smad3 were determined in HTG6PD and Δ1339-transduced A549-LG cells. β-Actin was used as the loading control. One representative example is shown out of three experiments

Discussion

G6PD is a well-known housekeeping enzyme whose major function is to maintain cellular redox homeostasis12,21,22, and studies in knockout mouse reveals that G6PD plays a fundamental role in embryonic development. However, the detailed mechanism regarding why its knockout is embryonically lethal has not been clearly elucidated. The evidence obtained in the current study indicates that G6PD plays an important role in embryonic development, partly by affecting the expression of adhesion molecules. G6pd knockdown in zebrafish can cause EMT or adhesion defects during embryonic development, whereas CDH1 cRNA coinjection can rescue such phenotype. Moreover, G6PD knockdown modulates the EMT process by impairing NOX/Smad3/miR-200b signaling. These findings suggest a possible mechanism through which G6PD status affects embryonic development (Fig. 1).

When the G6PD level is downregulated in cells, the cellular function of NOX is impaired, leading to the loss of redox signaling to induce the expressions of Smad3 and miR-200b. In such conditions, the expressions of E-cadherin and β-catenin are decreased, thus influencing the development of the embryo

The proposed mechanism concerning G6PD and the embryonic development of zebrafish (Fig. 1) is largely based on the novel findings of the current study, particularly that G6PD knockdown modulates the EMT process. Severe G6PD deficiency leading to embryonic lethality has been well documented. A mouse model has been used to demonstrate that G6PD is indispensable for the development of the embryo and placenta9. G6PD(−) hemizygous or homozygous embryos stop growing at E8.5 or E7.5, an important stage for establishing blood circulation in mice9,23,24,25. G6PD is required for placental development to support the trophoblast9, and it plays an embryoprotective role against the development of oxidative stress11. The zebrafish model demonstrates that severe g6pd knockdown results in the development of cardiac and kidney edema18. Notably, EMT plays a crucial role in embryogenesis26. E-cadherin, a key epithelial surface marker, is downregulated during EMT. The loss of E-cadherin leads to the breaking of cell junctions and contributes to the dissemination of neural crest cells during normal development27,28. E-cadherin expression is also involved in melanocyte development, especially in the migration from the neural crest29,30. β-Catenin is another essential protein in the EMT process, and it regulates cell movements, especially in gastrulation31,32. In the current study, G6PD knockdown impaired E-cadherin and β-catenin expression in cells and in the zebrafish model. Cardiac edema was observed in the g6pd morphants (as indicated by the arrowhead in Supplementary Figure 2b). CDH1 and G6PD cRNA coinjection rescued the developmental defects of g6pd morphants in zebrafish. Taken together, these data provide strong support to the notion that G6PD knockdown impairs embryonic development by influencing the expression of adhesion molecules.

A key player in the proposed pathway involving G6PD and embryonic development is NOX signaling, which uses NADPH as a substrate to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). NOX family members are responsible for redox signaling, and they have been discovered in the differentiation of various cell types such as neural crest cells33, cardiac muscle cells34, osteoblasts35, macrophages36, and renal profibrotic cells37. NOX-mediated redox signaling is also involved in cell-to-extracellular matrix interactions38,39,40 such as the anoikis molecular pathways. In the current study, NOX redox signaling modulated by G6PD was involved in the regulation of cell–cell interaction. Although NOX1 and NOX2 are the major isoforms in lung epithelial cells (as reported in another and in our previous study)6,41, NOX4 has also been implicated to be an essential mediator of Smad2/3 transcription factor activation in lung differentiation42. G6PD knockdown impaired p22phox expression, the common subunit of NOX1, NOX2, NOX3, and NOX4, and thus decreased the expression of E-cadherin and β-catenin via redox-mediated signaling, possibly by modulating the Smad3/miR-200b pathway. Our data support the notion that G6PD status regulates embryonic development via redox signaling mediated through the NOX pathway. Additional studies are needed to clarify the specific roles of the various isoforms of NOX in redox signaling in different tissues during embryonic development.

The downstream targets in G6PD-mediated NOX signaling are Smad3 and miR-200b. G6PD knockdown decreased Smad3 expression concomitant with miR-200b downregulation (Fig. 2). The Smad pathway has a critical role in the expression of genes controlling embryonic stem cell differentiation43,44,45. Evidence indicates that Smad proteins inhibit EMT43,46. Smad3 modulates EMT in a TGF-β-independent manner through the regulation of miR-200 clusters43. MiR-200b, which is easily induced by oxidative stress, plays a critical role in modulating EMT, embryonic stem cell differentiation47, and the progression of cardiac function48. The expression of miR-200b induces the pluripotency of somatic cells through Oct4 and Sox2 upregulation49, the two major focuses of stem cell biology50. Taken together, G6PD plays a cytoregulatory role in producing a low concentration of ROS to affect the Smad3/miR-200b pathway through the modulation of NOX-mediated signaling during embryonic development. These data also support the concept that appropriate redox homeostasis is essential for controlling embryonic development.

Another novel observation in the current study highlights that G6PD knockdown downregulated β-catenin expression. β-Catenin has a dual function in gene transcription and cell−cell adhesion51. Alignment analysis was used to compare the protein sequences in humans (Homo sapiens) and zebrafish (Danio rerio), and >90% identical sequences over entire β-catenin lengths were discovered (Supplementary Table 2). The homological identities of G6PD and E-cadherin were 76.4 and 48.1% between these two species, respectively. β-Catenin is the key regulator for directing several developmental processes, especially via Wnt signaling, and the formation of different body regions, such as those involving cardiac physiology52,53. Furthermore, β-catenin has also been implicated in regulating the differentiation of mesodermal cell lineages such as macrophages and the asymmetric cell division of C. elegans. We noted that G6PD knockdown inhibited β-catenin expression, and cardiac edema occurred in the g6pd morphants of zebrafish. Moreover, G6PD knockdown can lead to the loss of asymmetric cell division in the embryos of C. elegans12 and can prohibit macrophage differentiation (our unpublished data). These data indicate that the G6PD status affects cell differentiation and embryonic development, partly via the β-catenin pathway.

Our novel findings indicate that G6PD plays a regulatory role in modulating EMT, which could have major clinical implications in carcinogenesis. Cancer cells exhibit increased glycolysis and pentose cycle activity compared with normal cells. These metabolic alternations were thought to arise from the damage to the respiratory mechanism, and cancer cells were thought to compensate for this defect by increasing glycolysis. An increase in G6PD activity is observed in most cancer cell lines, and this promotes cell proliferation. Accordingly, mutations leading to the overexpression of β-catenin are closely associated with cancer progression54. This may explain why G6PD upregulation is correlated with cancer progression through the upregulation of β-catenin signaling. By contrast, Anelisa et al. used proteomic analysis to demonstrate that tumorigenic glioblastomas have low G6PD protein expression and increased cell migration55. Our observations that G6PD knockdown impairs β-catenin expression but enhances cell migration are consistent with those of Anelisa et al.55. Because cancer progression is complicated with the participation of multiple factors, the role of G6PD in carcinogenesis needs to be further delineated.

In summary, our study demonstrated that G6PD is a common feature for regulating cell–cell interactions by modulating the expression of adhesion molecules. The current study also indicates that G6PD plays a cytoregulatory role in redox signaling by influencing the NOX pathway, which is critical to many cellular functions. The impaired NOX/Smad3/miR-200b axis is, in part, the mechanism through which G6PD knockdown impairs E-cadherin and β-catenin expression. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that in embryonic development, G6PD plays an essential role as an integral component of the NOX/Smad3/miR-200b axis.

Materials and methods

Materials

The following antibodies were used: anti-G6PD (Genesis Biotech Inc., New Taipei, Taiwan), anti-E-cadherin, anti-N-cadherin, anti-β-catenin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), anti-β-actin (GeneTex Inc., Irvine, CA, USA), alexa fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG, alexa fluor 594 phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-ZEB1, anti-Smad3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-p22phox (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, and anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Recombinant human TGF-β1 was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). The g6pd targeting and nontarget Morpholinos were purchased from Gene Tools (Philomath, OR, USA).

Cell culture

MDCK cells were kindly provided by Dr. Shih Sin-Ru at the Chang Gung University and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Human adenocarcinoma epithelial cell lines (A549) were purchased from ATCC and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. These cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Thawed cells from liquid nitrogen were used for within the first five passages.

Plasmid construction and transduction by lentivirus system

pLKO.1.null-T and pLAS2w.Ppuro plasmids were purchased from the National RNAi Core Facility (Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan). The mini-cassette encoding shRNA against G6PD, p22phox, or scramble gene include overhangs that are allowed cloning into pLKO.1.null-T. Scramble shRNA was used as a negative control. The sequence of G6PD shRNA cassettes were (sense) 5′- CCGGGGATACACACATATTCATCATCCTCGAGGATGATGAATATGTGTGTATCCTTTTT-3′ and (anti-sense) 5′-AATTAAAAAGGATACACACATATTCATCATCCTCGAGGATGATGAATATGTGTGTATCC-3′. The sequence of p22phox shRNA cassettes were (sense) 5′- CCGGTACATGACCGCCGTGGTGAAGCTCGAGCTTCACCACGGCGGTCATGTATTTTT-3′ and (anti-sense) 5′-AATTAAAAATACATGACCGCCGTGGTGAAGCTCGAGCTTCACCACGGCGGTCATGTA-3′. The sequence of scramble shRNA cassettes were (sense) 5′-CCGGGCTCAACCTGTACAACATATTACTCGAGTAATATGTTGTACAGGTTGAGCTTTTT-3′ and (anti-sense) 5′-AATTAAAAAGCTCAACCTGTACAACATATTACTCGAGTAATATGTTGTACAGGTTGAGC-3′. The cDNA encoding human His-tagged G6PD (Accession No. NM_000402) or human SMAD3 (Accession No. NM_005902) was cloned into pLAAw.Ppuro plasmid (name as HTG6PD or SMAD3). Δ1339 was constructed by KOD plus polymerase (TOYOBO CO., Osaka, JP) using forward and reverse mutagenesis primers: (Forward) 5′-TGGACGTCTTCTGCAGGAGCCAGATGCACTTCG-3′ and (Reverse) 5′-CGAAGTGCATCTGGCTCCTGCAGAAGACGTCCA-3′. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with the packing plasmid (pCMV-ΔR8.91), pLKO.1 plasmids expressing shRNA/pLAS2w.Ppuro plasmids expressing cDNA, and envelope plasmid (pMD.G) to produce shRNA lentivirus according to instructions. The G6PD knockdown or overexpression were done by transducing with the recombinant lentivirus. The cDNA encoding human E-cadherin (Accession No.: NM_004360) was cloned into pCS2 + plasmid (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA).

G6PD activity

G6PD activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 340 nm by the reduction of NADP+ in the presence of glucose-6-phosphate as previously described5. Briefly, cells or zebrafish embryos were collected and scraped in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.05% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA and 1 mM NaF). Cell lysate was centrifugated and the supernatant was used in the assay. G6PD activity was analyzed by combining protein and assay buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8), 50 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NADP+ and 4 mM glucose 6-phosphate).

Western blot analysis

The cells and zebrafish embryos were scraped in lysis buffer, and centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to yield the extract. Samples were denatured, electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with an appropriate dilution of a primary antibody (1:1000) in Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% (w/v) Tween-20 (pH 7.4)) containing 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin. Membranes were incubated with a 1:4000 dilution of anti-rabbit or anti-mouse-HRP antibody for 1.5 h. The immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL reagents, with the signals captured by exposure to X-ray film. All experiments were performed independently at least in triplicate. (Unedited blots for all western blot experiments included in the supplementary data)

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA of cells was isolated using Trizol reagent and reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript III system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Primers were designed according to the sequences of human gene cDNAs and miRNA genes. The sequences of the primers used in reverse transcription and real-time PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Real-time PCR was performed using the IQ™ SyBr Green Supermix kit on an IQ5 Real Time Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative fold expression values were determined using the ΔΔCt method. The gene expression levels were normalized to the level of the reference gene (ACTB) and miRNA expression level was normalized to the level of small nuclear RNA U6. All experiments were performed independently at least in triplicate.

Immunofluorescence

A549 and MDCK cells were cultured in glass slides. After confluency, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100. Cells were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-E-cadherin (1:50, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-β-catenin (1:200, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-N-cadherin (1:50, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) overnight at 4 °C, and they were washed three times with PBS for 15 min each. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with alexa fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (1:100 for E- and N-cadherin and 1:400 for β-catenin, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and with 2 µg/ml of Hoechst 33342 dye for nuclear staining for 60 min at room temperature. After incubation, the samples were rinsed 3 times with PBS for 15 min each. Finally, the samples were examined under an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, JP).

Migration assays and wound-healing experiment

In vitro migration assays, a total of 8 × 104 cells in 200 μl serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle (DMEM) media were plated onto Millicell® culture plate inserts (8 μm pore size; Merk Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), and the lower chamber was immediately filled with 500 μl of DMEM media with 10% FBS as a chemoattractant. After 24 h of incubation in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C, the membranes were then fixed with methanol and stained by 0.2% crystal violet. Each individual experiment had triplicate inserts, and 5 microscopic fields were counted per insert. For wound-healing experiments, cells were plated in 6-well plates and cultured for confluency. Cells were serum-starved and scraped with a P200 tip (time 0), and pictures were taken at the 24 h time points then analyzed objectively using Image J. The percentage of wound closure at 24 h were measured by the size of the wound relative to that at 0 h in triplicate and the data were presented as mean ± SD.

Ethics statement and fish maintenance

All experiments were performesd in accordance with standard guidelines for zebrafish work and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chang Gung University (IACUC approval number: CGU16-045). Tü (wild type) zebrafish embryos were purchased from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (Oregon) and were raised, maintained, and paired under standard conditions. The embryos were staged according to the number of somites, hours postfertilization, and days postfertilization56.

RNA and morpholino injection

Capped RNA encoding the full coding sequences of human E-cadherin and G6PD were prepared as described previously57. Antisense morpholino (MO) oligonucleotides were purchased from Gene Tools (Philomath, OR, USA). The sequences of g6pd translation blocker and splice MOs were designed as the materials in previous study18. In brief, the g6pd MOs were combined in a 1:1 ration for delivery of 0.13 pmol for knockdown injection. Random MOs at 0.13 pmol were used for control injection. All injections were performed at the one- to two-cell stage and cRNAs or morpholinos were introduced into blastomeres.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± SD from replicated determinations. The student t test was used to compare the mean values from the two groups. Difference were regarded as significant the p value was <0.05.

References

Cappellini, M. D. & Fiorelli, G. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Lancet. 371, 64–74 (2008).

Luzzatto, L. & Seneca, E. G6PD deficiency: a classic example of pharmacogenetics with on-going clinical implications. Br. J. Haematol. 164, 469–480 (2014).

Wan, G. H., Tsai, S. C. & Chiu, D. T. Decreased blood activity of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase associates with increased risk for diabetes mellitus. Endocrine. 19, 191–195 (2002).

Gaskin, R. S., Estwick, D. & Peddi, R. G6PD deficiency: its role in the high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Ethn. Dis. 11, 749–754 (2001).

Lin, H. R. et al. Proteome-wide dysregulation by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) reveals a novel protective role for G6PD in aflatoxin B(1)-mediated cytotoxicity. J. Proteome. Res. 12, 3434–3448 (2013).

Lin, H. R., Wu, Y. H., Yen, W. C., Yang, C. M. & Chiu, D. T. Diminished COX-2/PGE2-Mediated Antiviral Response Due to Impaired NOX/MAPK Signaling in G6PD-Knockdown Lung Epithelial Cells. PLoS. ONE. 11, e0153462 (2016).

Wu, Y. H. et al. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Enhances Antiviral Response through Downregulation of NADPH Sensor HSCARG and Upregulation of NF-kappaB Signaling. Viruses 7, 6689–6706 (2015).

Tang, H. Y. et al. Inability to maintain GSH pool in G6PD-deficient red cells causes futile AMPK activation and irreversible metabolic disturbance. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 22, 744–759 (2015).

Longo, L. et al. Maternally transmitted severe glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency is an embryonic lethal. EMBO. J. 21, 4229–4239 (2002).

Yang, H. C. et al. Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency enhances germ cell apoptosis and causes defective embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell death & disease 4, e616 (2013).

Nicol, C. J., Zielenski, J., Tsui, L. C. & Wells, P. G. An embryoprotective role for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in developmental oxidative stress and chemical teratogenesis. FASEB. J. 14, 111–127 (2000).

Chen, T. L. et al. Impaired embryonic development in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient Caenorhabditis elegans due to abnormal redox homeostasis induced activation of calcium-independent phospholipase and alteration of glycerophospholipid metabolism. Cell Death Dis 8, e2545 (2017).

Nieto, M. A., Huang, R. Y., Jackson, R. A. & Thiery, J. P. Emt: 2016. Cell 166, 21–45 (2016).

Feng, X. H. & Derynck, R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 21, 659–693 (2005).

Yang, J. & Weinberg, R. A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev. Cell. 14, 818–829 (2008).

Mercado-Pimentel, M. E. & Runyan, R. B. Multiple transforming growth factor-beta isoforms and receptors function during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart. Cells. Tissues. Organs. 185, 146–156 (2007).

Wu, M. Y. & Hill, C. S. Tgf-beta superfamily signaling in embryonic development and homeostasis. Dev. Cell. 16, 329–343 (2009).

Patrinostro, X., Carter, M. L., Kramer, A. C. & Lund, T. C. A model of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in the zebrafish. Exp. Hematol. 41, 697–710 (2013). e692.

Babb, S. G. & Marrs, J. A. E-cadherin regulates cell movements and tissue formation in early zebrafish embryos. Dev. Dyn. 230, 263–277 (2004).

Chilosi, M. et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition-related proteins ZEB1, beta-catenin, and beta-tubulin-III in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Mod. Pathol. 30, 26–38 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Inhibition of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Could Enhance 1,4-Benzoquinone-Induced Oxidative Damage in K562 Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 3912515 (2016).

Yang, H. C., Wu, Y. H., Liu, H. Y., Stern, A. & Chiu, D. T. What has passed is prolog: new cellular and physiological roles of G6PD. Free. Radic. Res. 50, 1047–1064 (2016).

Cox, S. J. & Gunberg, D. L. Metabolite utilization by isolated embryonic rat hearts in vitro. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 28, 235–245 (1972).

Clough, J. R. & Whittingham, D. G. Metabolism of [14C]glucose by postimplantation mouse embryos in vitro. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 74, 133–142 (1983).

Ellington, S. K. In vitro analysis of glucose metabolism and embryonic growth in postimplantation rat embryos. Development 100, 431–439 (1987).

Li, X., Pei, D. & Zheng, H. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states during cell fate conversions. Protein Cell 5, 580–591 (2014).

Carmona-Fontaine, C. et al. Contact inhibition of locomotion in vivo controls neural crest directional migration. Nature. 456, 957–961 (2008).

Stramer, B. et al. Clasp-mediated microtubule bundling regulates persistent motility and contact repulsion in Drosophila macrophages in vivo. J. Cell. Biol. 189, 681–689 (2010).

Nishimura, E. K., Yoshida, H., Kunisada, T. & Nishikawa, S. I. Regulation of E- and P-cadherin expression correlated with melanocyte migration and diversification. Dev. Biol. 215, 155–166 (1999).

Mort, R. L., Jackson, I. J. & Patton, E. E. The melanocyte lineage in development and disease. Development 142, 1387 (2015).

Shimizu, T. et al. E-cadherin is required for gastrulation cell movements in zebrafish. Mech. Dev. 122, 747–763 (2005).

Larabell, C. A. et al. Establishment of the dorso-ventral axis in Xenopus embryos is presaged by early asymmetries in beta-catenin that are modulated by the Wnt signaling pathway. J. Cell. Biol. 136, 1123–1136 (1997).

Lee, J. E., Cho, K. E., Lee, K. E., Kim, J. & Bae, Y. S. Nox4-mediated cell signaling regulates differentiation and survival of neural crest stem cells. Mol. Cells. 37, 907–911 (2014).

Nadworny, A. S. et al. Nox2 and Nox4 influence neonatal c-kit(+) cardiac precursor cell status and differentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 305, H829–H842 (2013).

Mandal, C. C. et al. Reactive oxygen species derived from Nox4 mediate BMP2 gene transcription and osteoblast differentiation. Biochem. J. 433, 393–402 (2011).

Xu, Q. et al. NADPH oxidases are essential for macrophage differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 20030–20041 (2016).

Simone, S. et al. BMP-2 induces a profibrotic phenotype in adult renal progenitor cells through Nox4 activation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 303, F23–F34 (2012).

Chiarugi, P. & Giannoni, E. Anoikis: a necessary death program for anchorage-dependent cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 76, 1352–1364 (2008).

Groeger, G., Quiney, C. & Cotter, T. G. Hydrogen peroxide as a cell-survival signaling molecule. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 11, 2655–2671 (2009).

Paoli, P., Giannoni, E. & Chiarugi, P. Anoikis molecular pathways and its role in cancer progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1833, 3481–3498 (2013).

Fink, K., Duval, A., Martel, A., Soucy-Faulkner, A. & Grandvaux, N. Dual role of NOX2 in respiratory syncytial virus- and sendai virus-induced activation of NF-kappaB in airway epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 180, 6911–6922 (2008).

Amara, N. et al. NOX4/NADPH oxidase expression is increased in pulmonary fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and mediates TGFbeta1-induced fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts. Thorax. 65, 733–738 (2010).

Ahn, S. M. et al. Smad3 regulates E-cadherin via miRNA-200 pathway. Oncogene. 31, 3051–3059 (2012).

Moustakas, A., Souchelnytskyi, S. & Heldin, C. H. Smad regulation in TGF-beta signal transduction. J. Cell. Sci. 114(Pt 24), 4359–4369 (2001).

Massague, J. & Xi, Q. TGF-beta control of stem cell differentiation genes. FEBS Lett. 586, 1953–1958 (2012).

Pohl, M. et al. SMAD4 mediates mesenchymal-epithelial reversion in SW480 colon carcinoma cells. Anticancer. Res. 30, 2603–2613 (2010).

Zhang, J. et al. Retinoic Acid Induces Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation by Altering Both Encoding RNA and microRNA Expression. PLoS. ONE. 10, e0132566 (2015).

Feng, B. et al. miR-200b Mediates Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Diabetes. 65, 768–779 (2016).

Wang, G. et al. Critical regulation of miR-200/ZEB2 pathway in Oct4/Sox2-induced mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and induced pluripotent stem cell generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 2858–2863 (2013).

Rizzino, A. Concise review: The Sox2-Oct4 connection: critical players in a much larger interdependent network integrated at multiple levels. Stem Cell 31, 1033–1039 (2013).

Brembeck, F. H., Rosario, M. & Birchmeier, W. Balancing cell adhesion and Wnt signaling, the key role of beta-catenin. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16, 51–59 (2006).

Sokol, S. Y. Spatial and temporal aspects of Wnt signaling and planar cell polarity during vertebrate embryonic development. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 42, 78–85 (2015).

Grainger, S. et al. Wnt9a Is Required for the Aortic Amplification of Nascent Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Rep 17, 1595–1606 (2016).

Morin, P. J. beta-catenin signaling and cancer. Bioessays 21, 1021–1030 (1999).

Ramao, A. et al. Changes in the expression of proteins associated with aerobic glycolysis and cell migration are involved in tumorigenic ability of two glioma cell lines. Proteome. Sci. 10, 53 (2012).

Halpern, M. E. et al. Cell-autonomous shift from axial to paraxial mesodermal development in zebrafish floating head mutants. Development 121, 4257–4264 (1995).

Chung, P. C. et al. Zebrafish Her8a is activated by Su(H)-dependent Notch signaling and is essential for the inhibition of neurogenesis. PLoS. ONE. 6, e19394 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work is made possible by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST105-2320-B-182-031-MY2 to DTYC), from the Ministry of Education of Taiwan (EMRPD1G0181 to CGU), and from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (BMRP098 and CMRPD1F0461 to DTYC). We also thank miRNA plate form at Chang Gung University. This manuscript was edited by Wallace Academic Editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YHW, YCC, and DTYC co-designed the experiments with help from SHC; experiments were performed by YHW, YHL, and HYS. All authors analyzed results, wrote the manuscript, contributed substantially to the present work, then read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, YH., Lee, YH., Shih, HY. et al. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is indispensable in embryonic development by modulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the NOX/Smad3/miR-200b axis. Cell Death Dis 9, 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-017-0005-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-017-0005-8

This article is cited by

-

Caspase-11/4 and gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis contributes to podocyte injury in mouse diabetic nephropathy

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2021)

-

EEF1A2 interacts with HSP90AB1 to promote lung adenocarcinoma metastasis via enhancing TGF-β/SMAD signalling

British Journal of Cancer (2021)

-

Rewiring of purine metabolism in response to acidosis stress in glioma stem cells

Cell Death & Disease (2021)

-

Traditional Uyghur medicine Quercus infectoria galls water extract triggers apoptosis and autophagic cell death in colorectal cancer cells

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies (2020)

-

Difference of TGF-β/Smads signaling pathway in epithelial-mesenchymal transition of normal colonic epithelial cells induced by tumor-associated fibroblasts and colon cancer cells

Molecular Biology Reports (2019)