Abstract

Background

Cabazitaxel is a treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) after docetaxel failure. The FUJI cohort aimed to confirm the real-life overall and progression-free survival (OS, PFS) and safety of cabazitaxel.

Methods

Multicentre, non-interventional cohort of French mCRPC patients initiating cabazitaxel between 2013 and 2015, followed 18 months.

Results

Four hundred one patients were recruited in 42 centres. At inclusion, median age was 70, main metastatic sites were bones (87%), lymph nodes (42%) and visceral (20%). 18% had cabazitaxel in 2nd-line treatment, 39% in 3rd-line and 43% in 4th-line or beyond. All had prior docetaxel, and 82% prior abiraterone, enzalutamide or both. Median duration of cabazitaxel treatment was 3.4 months. Median OS from cabazitaxel initiation was 11.9 months [95% CI: 10.1–12.9]. In multivariate analyses, grade ≥ 3 adverse events, visceral metastases, polymedication, and >5 bone metastases were associated with a shorter OS. Main grade ≥ 3 adverse events were haematological with 8% febrile neutropenia.

Conclusion

Real-life survival with cabazitaxel in FUJI was shorter than in TROPIC (pivotal trial, median OS 15.1 months) or PROSELICA (clinical trial 20 vs 25 mg/m2, median OS, respectively, 13.4 and 14.5 months). There was no effect of treatment-line on survival. No unexpected adverse concerns were identified.

Study registration

It was registered with the European Medicines Agency EUPASS registry, available at www.encepp.eu, as EUPAS10391. It has been approved as an ENCEPP SEAL study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men and the fifth most common cause of cancer death worldwide.1 In France, prostate cancer ranks first in incidence in men (incidence rate 187 per 100,000), and third in mortality (18 per 100,000) in 2012.2 Thanks to screening resulting in early identification, prostate cancer is frequently diagnosed at an early stage, when it can be cured by radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. Around 10% of patients are diagnosed at a metastatic stage with usually a very poor prognosis.3 Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with anti-androgens or LH-RH derivatives has been shown to delay progression. However, over time most prostate cancers will acquire resistance to ADT. This is referred to as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). In addition, to the patients diagnosed at the metastatic stage most CRPC become metastatic (mCRPC).4

Treatment options for mCRPC have long been limited,5 with only mitoxantrone with prednisone being licensed for its palliative effect without survival benefit. In 2004, docetaxel in combination with prednisone was shown to improve overall survival (OS).6 Over the last decade, three additional treatments have been licensed for treatment of mCRPC following failure of docetaxel, the new generation taxane cabazitaxel7 and two androgen-receptor-targeted therapies, abiraterone acetate8 and enzalutamide,9 with similar results.10 The latter two agents have subsequently been licensed also for first-line treatment of mCRPC.

Cabazitaxel was approved as second-line treatment based on the results of the TROPIC trial, which enrolled 755 mCRPC patients progressing during or after docetaxel treatment.11 Cabazitaxel plus prednisone demonstrated a significant OS improvement compared to mitoxantrone plus prednisone (hazard ratio: 0.70 [95% confidence interval: 0.59–0.83]). The recommended dose of cabazitaxel is 25 mg/m² administered as a one-hour intravenous infusion every three weeks in combination with oral prednisone or prednisolone 10 mg administered daily throughout treatment.

Since then, the PROSELICA clinical trial has confirmed the non-inferiority of cabazitaxel 20 mg/m2 (C20) versus 25 mg/m² (C25) in 1200 post docetaxel mCRPC patients. Median OS, time to PSA progression and PSA response rate were 14.5 months, 6.8 months and 42.9%, for C25, respectively, and 13.4 months, 5.7 months and 29.5% for C20.12

At the time of the marketing authorisation of cabazitaxel in France in October 2011, the French Health Authorities requested a post-marketing study documenting the effectiveness and safety of cabazitaxel in everyday clinical practice. The FUJI study was designed to meet this request. The primary objective of FUJI was to evaluate OS in mCRPC patients treated by cabazitaxel in daily practice. Secondary objectives included PSA response, progression-free survival, profile of patients receiving cabazitaxel including analgesic use and safety of cabazitaxel.

Methods

Study design

FUJI (Follow-Up of Jevtana® in real life) is a French multicentre non-interventional cohort study of patients with mCRPC starting treatment with cabazitaxel between 1 September 2013 and 31 August 2015 and followed 18 months.

Participants

The methodology was the same as in real-life studies of other cancer treatments:13,14,15 in France, cabazitaxel is only available through hospital prescriptions on a named-patient basis. All hospitals dispensing cabazitaxel were identified between September 2013 and December 2014 from sales data provided by the manufacturer. The pharmacists of these centres were invited to participate in the study. Those who accepted provided a list and the contact details of the oncologists who had prescribed cabazitaxel during the study period. These oncologists were invited to participate in the study and if so, include in the study all patients who had received at least one cycle cabazitaxel, irrespective of the number of cycles received, except those who had been enrolled in a clinical trial. The patients who were enrolled by the oncologists were compared to dispensing records by the pharmacists to ensure full consecutive enrolment. If alive at the time of data compilation, patients were asked to confirm their non-opposition to the use of data.

Enrolment continued until the target sample size of 400 patients had been achieved.

Data collection

Clinical and prostate specific antigen (PSA) data were extracted from the hospital records during the eighteen-month period following the first administration of cabazitaxel, or until the patient died and entered into an electronic case report form by a dedicated clinical research assistant. All data collected were validated by the participating physician and included the following: date of first cabazitaxel administration, patient demographics, disease history including prior treatments, cabazitaxel treatment modalities, outcomes (clinical, biological, radiological), date of death, analgesic use and adverse events (AEs) reported during cabazitaxel treatment. Adverse events were coded using the current MedDRA classification and their severity was coded according to the grading system of the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology for the Classification of Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE v4.0). Adverse events requiring hospital admission were also identified.

Study end-points

The primary end-point was OS over eighteen months, calculated from first cabazitaxel administration. Secondary end-points were PSA response (defined by a PSA decrease of at least 50% from baseline) and progression-free survival (PFS) defined as in TROPIC16 (PSA and/or radiological and/or clinical progression or death). PSA progression was defined as an increase in PSA of at least 25% and of at least 2 ng/ml compared to the lowest post-cabazitaxel treatment value (PSA nadir), confirmed by a 2nd PSA value at least 3 weeks later. Radiological progression was defined by RECIST criteria version 1.0 as per physician judgment.17 Clinical progression was based on pain/symptoms and analgesic consumption as per physician judgment.

Statistical analysis

The target sample size (400 subjects) was chosen to estimate OS at eighteen months with a precision of 4.9%, considering a median OS in TROPIC trial of 15.1 months.16 OS and PFS were estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Cox proportional hazard models over the eighteen-month follow-up period were used to identify risk factors associated with death or progression. The variables entered into the Cox models are listed in supplementary data Table 1, and pertain to factors occurring before cabazitaxel, to patient status at first cabazitaxel injection and to per-treatment events. Survival estimates were also provided for patients with synchronous or metachronous metastases.

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS® (SAS Institute, version 9.4, Cary, USA), according to a statistical analysis plan defined prior to data lock.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with all relevant national legislation and guidelines for observational studies, with approval from the French national data-protection Agency (CNIL). The study protocol was submitted to and approved by the French health authorities as part of the post-marketing commitments of the manufacturer of cabazitaxel (Sanofi-Aventis). All patient data in the study database were anonymised. The study was registered with the EU PAS registry (ENCEPP/SDPP/10391).

Results

Study population

Overall, 261 hospital pharmacies that had dispensed cabazitaxel at least once between September 2013 and December 2014 were contacted and invited to participate in the study. Of these, 93 pharmacies (35.6% of those contacted) accepted to participate and provided contact details of 234 physicians who had prescribed cabazitaxel. One hundred twenty eight of these agreed to participate, and 79 had recruited patients into the study when the target patient sample size was met. When recruitment was stopped, 401 patients had been recruited, between September 2013 and August 2015, in 42 centres. The patient recruitment process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. At cabazitaxel initiation, median age was 70 years median time elapsed since prostate cancer diagnosis was 5.5 years, 20% had visceral metastases and 15.7% had an ECOG PS ≥ 2. At cancer diagnosis, median Gleason score was 7. About 40% had synchronous metastases. All patients had been treated with docetaxel before cabazitaxel. Prior to cabazitaxel initiation, 18.0% had received only one life-extending therapy (LET) line for mCRPC (docetaxel), 38.7% two previous LET lines, 22.7% 3 previous LET lines and 20.7% 4 or 5 previous LET lines. Most patients (81.5%) had been treated previously by novel androgen-receptor (AR)-targeted agents (abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide or both). The majority of patients (n = 389; 97.0%) had associated comorbidities, notably cardiovascular (69.2%), digestive (46.0%), endocrine (44.5%), urogenital (39.3%), musculoskeletal (33.4%) and respiratory (30.1%) disorders.

Treatment with cabazitaxel

Cabazitaxel was most often administered every three weeks (n = 364, 90.8%) at a starting dose of 25 mg/m2 (n = 184, 50.5%). Other administration schedules were: <25 mg/m² every 3 weeks (n = 160, 44.0%), >25 mg/m² every 3 weeks (n = 13, 3.6%), 12–17 mg/m² every 2 weeks (n = 36, 9.2%). In 125 patients (31.2%), the dose was reduced over the course of treatment.

The median duration of cabazitaxel treatment was 3.4 months with a median of five cycles. Among patients who had discontinued cabazitaxel at 18 months (95%), the main reasons for discontinuation were disease progression or disease-related death (83.2%), or the occurrence of AEs (15.2%).

Survival outcome and response rates

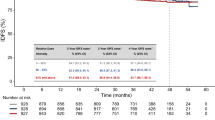

The 18-month OS rate was 32.4% [95% CI: 27.8–37.1] with a median OS of 11.9 months [10.1–12.9]. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve is presented in Fig. 2a. In multivariate Cox analysis, factors independently associated with a shorter OS were related to pre-treatment variables: <10 years since PC diagnosis, hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.52 [1.04–2.17], progression during docetaxel treatment (1.69 [1.13–2.53]) or within 3 months after the last docetaxel injection (1.51 [1.07–2.14]), when the patient had received two or more Life-extending treatments before cabazitaxel (1.39 [1.00–1.92]), when the interval between the last docetaxel administration and first cabazitaxel injection was less than 6 months (1.41 [1.03–1.92]); to patient status at first use of cabazitaxel: presence of visceral metastases (1.98 [1.40–2.80]) or more than five bone metastases (1.74[1.20–2.53]), plasma prostate specific antigen > 135 ng/mL (1.36 [1.01–1.82]) or when there were more than 5 concomitant non-cancer treatments at first cabazitaxel injection (1.74 [1.23–2.45]). Finally, overall survival was shorter when there was at least one grade ≥ 3 adverse event during cabazitaxel treatment (2.05 [1.53–2.73]).

In the pre-specified subgroup analyses, median OS from first cabazitaxel administration ranged from 9.9 months [6.6–12.9] for patients with one previous LET line, 12.1 months [8.5–15.0] for patients with two previous LET lines, 12.9 months [10.0–14.7] for patients with three previous LET lines and 11.7 months [8.1–13.5] for patients with four previous LET lines before cabazitaxel initiation (see supplementary data e-Fig. 1). No significant differences were observed in OS between patients with synchronous or metachronous metastases or in patients having previously been treated with different disease-modifying cancer treatments.

Progression-free survival

The median PFS was 3.9 months [95% CI: 3.5–4.6] (Fig. 2b). The PFS rate was 32.4% [27.9–37.0] at 6 months and 3.1% [1.7–5.1] at 18 months. In the multivariate Cox analysis, factors independently associated with a shorter PFS at 6 months were intensification of analgesic use to level III (HR = 2.31 [1.70–3.14]), disease progression within 3 months of the last docetaxel administration and before cabazitaxel initiation (HR = 2.30 [1.68–3.15]), and at least one AE of grade ≥ 3 during cabazitaxel treatment (HR = 1.50 [1.14–1.97]). No differences in PFS were observed between the pre-specified subgroups.

The overall response rate varied from 11.0% (radiological response) to 38.9% (PSA response) depending on the criterion used (Table 2). However, regardless of the criterion, <3% of patients achieved a complete response.

PSA response was available for 258 patients (64.3%) (Fig. 3). In 103 patients (39.9%), PSA decreased by ≥50%, with a median time to reach this threshold of 4.1 months. The median time to PSA progression was 5.0 months.

Change in PSA concentrations during cabazitaxel treatment from pre-treatment values. Each line represents the on-treatment change in PSA in an individual patient, ranked from the largest increase (cropped at 100%) to the largest decrease. An increase of more than 100% in best PSA response concerned 33 patients of the 258 evaluable patients

Adverse events

Almost all patients (99.0%) experienced at least one AE during cabazitaxel treatment AEs requiring hospitalisation occurred in 41.1% of patients; the first AE occurred during the first or second cabazitaxel administration for half of patients (52.1%). At least one AE of Grade ≥ 3 was observed for 55.4% of patients, and these required hospitalisation in 26.6%.

There was no difference in the event rates for grade ≥ 3 AE according to the number of previous treatment lines, from 54.2% with just one previous line, to 45.8% with four or five treatment lines before cabazitaxel.

Adverse events are presented by System-Organ Class (SOC) and Preferred Term (PT) in Table 3. The most frequent AEs were haematological, in particular anaemia (92.5%), thrombocytopaenia (28.9%) and neutropaenia (26.9%). Other frequent AEs were fatigue and asthenia (69.6%), diarrhoea (39.9%), nausea (29.9%). GCSF was systematically used before each cabazitaxel infusion in 45.9% of patients. This was 45.8% when there was one treatment line before cabazitaxel, 54.8% for two treatment lines, 31.9 % for three treatment lines, and 44.6% for four or five treatment lines before cabazitaxel.

The most frequent grade ≥ 3 AEs were anaemia (26.9%), neutropenia (15.0%) including febrile (8%), leukopenia (9.5%), renal failure (7.2%), thrombocytopenia (5.2%) and septicaemia and septic shock (5.0%). Six cabazitaxel-related deaths occurred, five of which were related to sepsis or septic shock with febrile neutropenia. These patients had at least one G-CSF treatment before or during the cycle when febrile neutropenia occurred, except for one patient who had an infectious shock after the first cabazitaxel administration.

Analgesic use

Use of Level I analgesics was more common during cabazitaxel treatment (70.3% of patients) than before (44.9%) or after (58.6%). Of the patients who were taking analgesics at cabazitaxel initiation, 30.9% reduced their analgesic consumption during the follow-up period. Analgesic consumption increased in 41.2% of patients. After discontinuation of cabazitaxel, the frequency of analgesic use remained stable in 67%. These data are summarised in supplementary data Table 2.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of cabazitaxel in the treatment of mCRPC patients in everyday clinical practice in France. In this heavily treated population (39% received cabazitaxel in 3rd line, 23% in 4th line, 21% in 5th line or beyond), the rate of OS at 18 months after cabazitaxel initiation was 32.4%. The most frequent AEs reported were haematological reactions, with 8% febrile neutropenia.

The strengths of this study were the relatively large sample size (n = 401), the broad eligibility criteria that encompassed all mCRPC patients treated with cabazitaxel whatever the treatment line, and the requirement that participating physicians include all their patients treated with cabazitaxel during the study recruitment period. In addition, follow-up was complete, and the status of all patients could be assessed at eighteen months. These features ensured that outcome could be determined with precision and be representative of outcome of mCRPC patients treated with cabazitaxel in everyday oncology practice in France. Nonetheless, some selection bias may be inherent to the voluntary participation of pharmacists and investigators. Around half the hospital pharmacies and around half the identified prescribers refused to participate in the study, so it is not certain that management of patients in these centres that did not participate was comparable to that observed in this study. Nonetheless, a previous study evaluating the impact of prescriber participation found no difference in patient outcomes between participating and non-participating physicians.18

The median OS was shorter here (11.9 months [10.1–12.9] than in the Phase 3 TROPIC trial,11 (15.1 months [14.1–16.3])) or in the PROSELICA trial (Median OS 13.4 and 14.5 months for the initial cabazitaxel doses of 20 and 25 mg/m2).12 There are two potential explanations for these differences. First, patients included in FUJI were in general older and more fragile than those enrolled in the clinical trials, where severe eligibility criteria were applied. For example, patients with poor performance status (ECOG score > 2) or with severe haematological, hepatic, renal or cardiac comorbidities were excluded in clinical trials. In contrast, eligibility criteria in FUJI were broad and all mCRPC patients treated by each participating investigator over the study period were enrolled, whatever their health status and whatever the duration of treatment. Indeed, if TROPIC inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to FUJI, only two of 401 patients (0.5%) would have been eligible. Also, in TROPIC, all patients received cabazitaxel in second-line after docetaxel. In contrast with TROPIC, at the time of FUJI abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide were both available and only 18% received cabazitaxel immediately after docetaxel, with a median OS of 9.9 months. A possible explanation for the shorter OS as compared to TROPIC (15.1 months) may be that such patients might have had aggressive clinical features thought unlikely to respond to new AR-targeted agents. A phase 2 randomised controlled trial has indeed shown that taxanes were more effective than novel AR-targeted agents (abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide) in poor-prognosis mCRPC patients.19 Another explanation may be that patients with a very compromised status and short expected survival are often not included in clinical trials, whereas they are part of real-life observational studies.

In FUJI, median OS with cabazitaxel in fourth line setting or beyond after novel AR-targeted agents was 12.9 months [10.0–14.7] indicating that cabazitaxel retains its activity after these patients. In the multivariate analysis, multiple previous treatment lines and a high burden of comorbidity (as witnessed by the number of concomitant medications being taken), were independent predictors of mortality.

Effectiveness data on cabazitaxel in everyday oncology practice have also been published from the compassionate use programs established in the Netherlands,20 Korea21 and Germany22 before cabazitaxel was commercially available. In the study from the Netherlands, median OS was 8.7 months [IQR: 6.0–15.9], which is close to the value observed in the FUJI study and again shorter than that reported in TROPIC. On the other hand, the Korean study reported a longer median OS (16.5 months [95% CI: 12.1–20.9]), close to the value reported in TROPIC. The German study reported mean OS (13.9 months [range: 0.7–35.8]) rather than median OS and is thus not really comparable. The publications on the Italian23 and Spanish24 compassionate use programs did not present data on survival.

The safety profile of cabazitaxel in FUJI was essentially similar to that observed in TROPIC or PROSELICA, and no unanticipated safety issues arose. The proportion of patients presenting AEs of severity Grade 3 or 4 was 55.4% in FUJI compared to 57.4% in TROPIC11 and 39.7% (20 mg/m2) or 54.5% (25 mg/m2) in PROSELICA.12 In all studies, haematological AEs were the most common. Although anaemia was reported at a relatively similar frequency in both studies (90% in FUJI and 97% in TROPIC), the reporting frequency of neutropenia was much lower in FUJI (26.9%) than in TROPIC (94%) or PROSELICA (41.8% and 73.3%). This may be explained by less intensive biological monitoring in real-life practice than in TROPIC, in which neutrophils were systematically measured at nadir, 8–10 days after each administration of cabazitaxel and G-CSF more systematically given.25 The frequency of febrile neutropenia was identical in both studies (8%), compared to 2.1 and 9.6% for C20 and C25, respectively, in PROSELICA.12 Six cabazitaxel-related deaths due to sepsis or septic shock, with febrile neutropenia in five, were reported in the FUJI study (1.5%), emphasising the importance of using prophylactic G-CSF from cycle 1 as per EORTC guidelines and carefully monitoring neutrophil counts in patients receiving cabazitaxel. In the PROSELICA C20 and C25 treatment groups, 2.1% and 3.2% of patients, respectively, died within 30 days of the last dose of cabazitaxel as a result of AEs.12 The occurrence of AEs was not a major reason for stopping treatment with cabazitaxel, concerning only around one in eight patients. The safety profile of cabazitaxel in FUJI can also be compared with the safety data collected in the European compassionate use program for cabazitaxel, which enrolled 746 patients.26 The frequency of adverse event reporting was generally higher in the compassionate use program than in the FUJI study, except for neutropenia. The compassionate use program reported 17.0% of patients with Grade 3 neutropenia, 5.5% with febrile neutropenia, 1.3% with neutropenic sepsis and seven deaths related to neutropenia or its complications.

Cabazitaxel was generally used as recommended in the prescribing information at the time of the study. The licensed indication (mCRPC, after docetaxel) was respected in all patients. Although the recommended treatment regimen of one cycle every three weeks was followed by most patients (90.8%), the recommended starting dose of 25 mg/m² was used in only half of the patients. Although dose reductions are recommended in patients with hepatic failure, the number of patients with hepatic disease (n = 47) could not account for the large number of patients starting at the lower dose of 20 mg/m² (196 patients). The fact that patients were less fit than in TROPIC (only 0.5% satisfied inclusion/exclusion criteria of TROPIC), may have contributed to it. The PROSELICA Phase 3 clinical trial12 has also demonstrated that a lower starting dose of 20 mg/m² was non-inferior to the approved dose of 25 mg/m² with a lower incidence of AEs. Prescribers may have been aware of that study and anticipated its results.27

In conclusion, this real-life cohort study of cabazitaxel in mCRPC patients in France demonstrates that median OS at 18-months is slightly lower in everyday oncology practice than what was reported in the pivotal clinical trial, due to the presence of features of poor prognosis at baseline and use of cabazitaxel in 3rd line or beyond in 82% of patients. There were no unexpected safety issues, with severe neutropenia being the most important risk to consider when prescribing cabazitaxel.

References

Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Dikshit, R., Eser, S., Mathers, C., Rebelo, M. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. cancer 136, E359–E386 (2015).

Ferlay, J., Steliarova-Foucher, E., Lortet-Tieulent, J., Rosso, S., Coebergh, J. W., Comber, H. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Euro. J. Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 49, 1374–1403 (2013).

Patrikidou, A., Loriot, Y., Eymard, J. C., Albiges, L., Massard, C., Ileana, E. et al. Who dies from prostate cancer? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 17, 348–352 (2014).

Jegu, J., Tretarre, B., Velten, M., Guizard, A. V., Danzon, A., Buemi, A. et al. [Prostate cancer management and factors associated with radical prostatectomy in France in 2001]. Prog. Urol. 20, 56–64 (2010).

Nuhn, P., De Bono, J. S., Fizazi, K., Freedland, S. J., Grilli, M., Kantoff, P. W., et al. Update on systemic prostate cancer therapies: management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in the era of precision oncology. Euro. Urol. 75, 88–99 (2019).

Tannock, I. F., de Wit, R., Berry, W. R., Horti, J., Pluzanska, A., Chi, K. N. et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 1502–1512 (2004).

Tsao, C. K., Cutting, E., Martin, J. & Oh, W. K. The role of cabazitaxel in the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Therapeutic Adv. Urol. 6, 97–104 (2014).

Caffo, O., Veccia, A., Kinspergher, S. & Maines, F. Abiraterone acetate and its use in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer: a review. Future Oncol. (Lond., Engl.) 14, 431–442 (2018).

Baciarello, G. & Sternberg, C. N. Treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with enzalutamide. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 106, 14–24 (2016).

Summers, N., Vanderpuye-Orgle, J., Reinhart, M., Gallagher, M. & Sartor, O. Efficacy and safety of post-docetaxel therapies in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 33, 1995–2008 (2017).

de Bono, J. S., Oudard, S., Ozguroglu, M., Hansen, S., Machiels, J. P., Kocak, I. et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet 376, 1147–1154 (2010).

Eisenberger, M., Hardy-Bessard, A. C., Kim, C. S., Geczi, L., Ford, D., Mourey, L. et al. Phase III Study Comparing a Reduced Dose of Cabazitaxel (20 mg/m(2)) and the Currently Approved Dose (25 mg/m(2)) in Postdocetaxel Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer-PROSELICA. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 3198–3206 (2017).

Fourrier-Reglat, A., Noize, P., Facon, T., Fermand, J. P., Fitoussi, O., Marit, G. et al. Real-life patterns of use and effectiveness of bortezomib: the VESUVE cohort study. Leuk. Lymphoma 55, 848–854 (2014).

Fourrier-Reglat, A., Smith, D., Rouyer, M., Benichou, J., Guimbaud, R., Becouarn, Y. et al. Survival outcomes of bevacizumab in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer in a real-life setting: results of the ETNA cohort. Target Oncol. 9, 311–319 (2014).

Rouyer, M., Francois, E., Cunha, A. S., Monnereau, A., Noize, P., Robinson, P. et al. Effectiveness of cetuximab as first-line therapy for patients with wild-type KRAS and unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer in real-life practice: results of the EREBUS cohort. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 17, 129–139 (2018).

Bahl, A., Oudard, S., Tombal, B., Ozguroglu, M., Hansen, S., Kocak, I. et al. Impact of cabazitaxel on 2-year survival and palliation of tumour-related pain in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated in the TROPIC trial. Ann. Oncol. 24, 2402–2408 (2013).

Therasse, P., Arbuck, S. G., Eisenhauer, E. A., Wanders, J., Kaplan, R. S., Rubinstein, L. et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 92, 205–216 (2000).

Fourrier-Reglat, A., Droz-Perroteau, C., Benichou, J., Depont, F., Amouretti, M., Begaud, B. et al. Impact of prescriber nonresponse on patient representativeness. Epidemiology (Camb., Mass) 19, 186–190 (2008).

Chi, K. N., Taavitsainen, E., Iqbal, N., Ferrario, C., Ong, M., Wadhwa, D. et al. A randomized phase 2 study of cabazitaxel (CAB) vs (ABI) abiraterone or (ENZ) enzalutamide in poor prognosis metastatic castration-resistant prostatic cancer. Ann. Oncol. 29(suppl_8), viii271–viii302 (2018).

Wissing, M. D., van Oort, I. M., Gerritsen, W. R., van den Eertwegh, A. J., Coenen, J. L., Bergman, A. M. et al. Cabazitaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results of a compassionate use program in the Netherlands. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 11, 238–50 e1 (2013).

Lee, J. L., Park, S. H., Koh, S. J., Lee, S. H., Kim, Y. J., Choi, Y. J. et al. Effectiveness and safety of cabazitaxel plus prednisolone chemotherapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostatic carcinoma: data on Korean patients obtained by the cabazitaxel compassionate-use program. Cancer Chemother. Pharm. 74, 1005–1013 (2014).

Heidenreich, A., Scholz, H. J., Rogenhofer, S., Arsov, C., Retz, M., Muller, S. C. et al. Cabazitaxel plus prednisone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel: results from the German compassionate-use programme. Eur. Urol. 63, 977–982 (2013).

Bracarda, S., Gernone, A., Gasparro, D., Marchetti, P., Ronzoni, M., Bortolus, R. et al. Real-world cabazitaxel safety: the Italian early-access program in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Future Oncol. (Lond., Engl.) 10, 975–983 (2014).

Castellano, D., Anton Aparicio, L. M., Esteban, E., Sanchez-Hernandez, A., Germa, J. R., Batista, N. et al. Cabazitaxel for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: safety data from the Spanish expanded access program. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 13, 1165–1173 (2014).

Oudard, S. TROPIC: Phase III trial of cabazitaxel for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Future Oncol. (London, England) 7, 497–506 (2011).

Heidenreich, A., Bracarda, S., Mason, M., Ozen, H., Sengelov, L., Van Oort, I. et al. Safety of cabazitaxel in senior adults with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results of the European compassionate-use programme. Euro. J. Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 50, 1090–1099 (2014).

Smith, D., Terrebonne, E., Rouyer, M., Blanc, J. F., Breilh, D., Pedeboscq, S. et al. Chemotherapy and targeted agents for colorectal cancer in a real-life setting anticipate guidelines: the COLCHIC cohort study. Fundam. Clin. Pharm. 27, 113–119 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank ADERA for legal, human resource and management support that made this study possible. The authors would like to thank the investigators for their participation in the study.

FUJI Investigators

Samir Abdiche7, Elisabeth Angellier8, Dominique Beal-Ardisson9, Guillaume Bera10, Jean-François Berdah11, Olivier Bernard12, Anne-Sophie Blanc13, Isabelle Bonnet14, Florence Borde15, Mathieu Bosset16, Fabien Brocard17, Sylvie Cailleres18, Damien Carlier19, Elisabeth Carola20, Christine Clippe21, Corinne Dagada22, Ariane Darut-Jouve23, Jérôme Dauba24, Christine Dolmazon25, Patrick Dube26, Mounira El Demery27, Philippe Evon28, François Guichard29, Ali Hasbini30, Benjamin Hoch31, Ludmila Hu32, Brigitte Laguerre33, Hortense Laharie34, Nathalie Lemoine35, Nadia Levasseur36, Christophe Louvet37, Delia Molnar38, Isabelle Moullet39, Sophie Nahon40, Stéphane Oudard41, Jean-Briac Prevost42, Frank Priou43, Mansour Rastkhah44, Stéphane Remy45, Jean-Louis Reynoard46, Hamida Talbi47, Youssef Tazi48, Erika Viel49, Stéphane Vignot50 and Laurent Vives51

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors participated in the different aspects of the study. Overall design of the study: M.R., S.O., F.J., K.F., F.T., A.F.R., N.M. Operational aspects of the study: M.R., S.L., E.G., A.B., C.D.P. Statistical analysis plan and statistical analysis: J.J., C.L. Interpretation of the results: M.R., S.O., F.J., K.F., F.T., A.F.R., N.M. Study report first and last draft: N.M. All authors reviewed and amended the study manuscript repeatedly and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

N.M. has received fees from Sanofi-Aventis for training in pharmacoepidemiology, independent from and before this study. He has received training or consulting fees from other pharmaceutical companies not involved in this study or in the treatment of prostate cancer. A.F.R. reports no conflicting interests. Bordeaux PharmacoEpi has several dozen ongoing studies financed by pharmaceutical companies outside the scope of this study. The salaries of Bordeaux PharmacoEpi employees (M.R., J.J., C.L., S.L., E.G., A.B., Cd.P.) are derived in part from the funding of this study, but they have no direct conflict of interest. S.O.: declares honoraria from Sanofi, Astellas, Janssen, Bayer. F.J.: declares scientific Board, consulting or lecture during symposium: Pfizer, Sanofi, Novartis, Bayer, Ipsen, Roche, Astra Zeneca, Tesaro, Astellas, Janssen, BMS, MSD; travelling: Tesaro, Janssen, Astra-Zeneca, BMS, Roche. K.F.: declares participation to advisory boards/honorarium for Astellas, AAA, Bayer, Clovis, Curevac, Incyte, Janssen, MSD, Orion, Sanofi. F.T. is head of the Centre de Pharmacoépidémiologie (Cephepi) of the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris and of the Clinical Research Unit of Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital. Both these structures have received research funding, grants and fees for consultant activities from a large number of pharmaceutical companies, that have contributed indiscriminately to the salaries of its employees. She did not receive any personal remuneration from these companies.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was evaluated by the regional committee for the protection of patients in clinical research (Sud-Ouest Outre-Mer III) on 18 May 2015, waiving individual patient consent for this non-interventional study. It was approved by the consultative committee on scientific research (CCTIRS) on May 7, 2015 (#CCTIRS15.583), and by the national data-protection committee (CNIL) on December 24, 2015 (# DR-2015-573). The study was performed according to the declaration of Helsinki in its latest version.

Funding

The study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis, the company that markets cabazitaxel. The funder had no impact on the final protocol, which was approved by the French regulatory authorities, on the study conduct, on data analysis or the content of the present paper, though it was given the opportunity to comment, according to the ENCEPP Code of conduct.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Data availability

The data of this study are available, as per the ENCEPP code of conduct available at www.encepp.eu, upon providing the reasons for the request and the proposed study protocol.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The members of the FUJI Investigators are listed above the Acknowledgements.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rouyer, M., Oudard, S., Joly, F. et al. Overall and progression-free survival with cabazitaxel in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in routine clinical practice: the FUJI cohort. Br J Cancer 121, 1001–1008 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0611-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0611-6

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances and future perspectives in the therapeutics of prostate cancer

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2023)

-

Comprehensive analysis of the associations between clinical factors and outcomes by machine learning, using post marketing surveillance data of cabazitaxel in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer

BMC Cancer (2022)

-

TACR2 is associated with the immune microenvironment and inhibits migration and proliferation via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in prostate cancer

Cancer Cell International (2021)

-

Prognostic significance of third-line treatment for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: comparative assessments between cabazitaxel and other agents

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2021)

-

Stellenwert von Cabazitaxel in der Therapiesequenz des kastrationsresistenten Prostatakarzinoms gefestigt – die CARD-Studie

Der Onkologe (2020)