Abstract

Aims To investigate factors influencing oral health behaviours and access to dental services for asylum seekers and refugees (ASRs).

Methods A qualitative research study using purposeful sampling was undertaken in South West England. Online semi-structured interviews with stakeholders working with or supporting ASRs were analysed through reflexive thematic analysis.

Results Twelve participants providing support to ASRs in various capacities participated. Two interviewees had lived experience of forced displacement and the UK asylum process. Key themes into what hinders ASRs' oral health care were: prioritising safety and survival; variations in cultural norms and practice; lack of knowledge about dental care; financial hardship and affordability of care; a gulf of understanding of what dental care would be like and experiences of it; and structures of dental services that leave vulnerable groups behind. Opportunities for improving oral health care were: accessible oral health education; partnership working and creating supportive environments; translation; providing culturally sensitive and person-centred care; and incorporating ASRs' views into service design.

Conclusions Several factors affect to what extent ASRs can and are willing to engage with oral health care. Co-developing accessible and relevant prevention programmes and ensuring equitable access to dental services for ASRs is important. Future research should explore ASRs' views and experiences of dental care and explore informed suggestions on how to optimise oral health promotion and provision of care.

Key points

-

Several factors affect to what extent asylum seekers and refugees can and are willing to engage with oral health care.

-

Co-developing accessible and relevant prevention programmes and ensuring equitable access to dental services for asylum seekers and refugees is imperative.

-

Incorporating 'cultural competence' into practice can optimise care quality.

-

Future research is needed to explore the views and experiences of asylum seekers and refugees accessing and receiving care in the UK, as well as their recommendations on optimising oral health promotion and care provision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The scale of global forced displacement has reached a record level.1 According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, by the end of 2019, 79.5 million people worldwide had been forcibly displaced due to war, violence, human rights violations, or other persecutory events.1 Among these, 26 million people are refugees and 4.2 million are people seeking asylum.1 A refugee is defined as a person who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted, has left their country and is unable to or unwilling to return home due to fear of the consequences of doing so.2 A person whose application for international protection has not yet been confirmed is referred to as an asylum seeker.1 In the UK, by the end of 2019, there were 133,094 refugees and 61,968 pending asylum cases.1

Asylum seekers and refugees (ASRs) often undergo long, turbulent and dangerous migration trajectories to reach safety. ASRs are considered a vulnerable group who experience social exclusion.3 They often present with significant and complex health needs and poorer health outcomes compared to the general population.4,5 Although data on oral health needs of ASRs in the UK are sparse, wider literature indicates that the burden of oral diseases and unmet treatment needs among this group are significant.6,7,8 Caries and periodontal disease are highly prevalent among ASRs.8 Upon arriving in the host country, it is not uncommon for ASRs to require urgent dental treatment and thereafter, they tend to visit a dentist only when experiencing a dental problem, such as dental pain.9

The Asylum seekers and Refugee Health Screening Programme in Plymouth has been in operation for more than twenty years. Recent data from this programme have shown that as many as 40% of 541 ASRs who underwent health examinations reported dental issues.10 Moreover, dental issues are the second highest reported unmet health need for this group.10 Similarly, in Wales, among this population, dental issues were the most frequent reason for recent contact with the healthcare system.11

ASRs are not a homogenous group of peoples. They have different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds which give rise to diverse oral health perceptions, knowledge and practices.8 These factors, coupled with healthcare system characteristics and turbulent journeys to safety, may influence ASRs' experiences, perceptions and intentions to access care.12 Access to dental care is a significant predictor of oral health status.8 Barriers to access can perpetuate oral health inequalities for vulnerable people.13 In this study, access is conceptualised as 'the opportunity to identify healthcare needs, to seek healthcare services, to reach, to obtain or use healthcare services and to actually have a need for services fulfiled'.14

Despite extensive normative and subjective dental need, existing literature demonstrates that access to dental care for ASRs in host countries is limited and fraught with challenges.8,12 A better understanding of the factors influencing oral health care is required to improve the delivery of these services and to design targeted and effective interventions. Therefore, this study aims to investigate factors influencing oral health care (oral health behaviours and access to dental care) for ASRs.

Methods

Research team and reflexivity

The authorship team consists of individuals with an academic, clinical and/or third sector background, all of whom have experience conducting research, providing healthcare to ASRs or advocating for equitable healthcare to individuals experiencing social exclusion. The first author (MP) who conducted the interviews and was involved in the analysis of data is an academic dental researcher from a non-clinical background. We believe that this enabled participants to speak openly and without reserve about the challenges inherent in the dental system and lessened the unequal power balance that can exist between participants and clinician researchers.15 Furthermore, MP has extensive experience in oral health inequalities and health services research and has been involved in ASR engagement on a volunteer basis which gave her intimate knowledge of service structures and barriers to care.

Study design

This was a qualitative research study, which adopted a critical realist position. The latter argues that a reality exists and operates independently of people's awareness or knowledge of it and is mediated by beliefs and perceptions.16,17 The current study adopted the critical realist position that there is a reality, independent of human construction and you can gain insight into people's experiences of this reality through their accounts. However, these insights will always be influenced and limited by our own experiences, perspectives and approach taken to understand another's experiences. Purposeful sampling was employed to identify and recruit people aged 18 years and above of any gender, working with or supporting ASRs in Plymouth city in various capacities. Individuals were identified by the principal investigator and selected on the basis that they were knowledgeable about or experienced with our phenomenon of interest (that is, the oral health care of asylum seekers and refugees).18 Participants were approached via email. All participants provided written informed consent for their participation in the study. Although we were about to start approaching ASRs for participation in the study, interviews were halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Semi-structured interviews (30-45 min) were conducted using Voice over Internet Protocol technologies, for example, Zoom and Microsoft Teams. The interviews were planned to take place face-to-face; however, due to the pandemic, ethical approval was obtained to conduct these online. The interview guide was informed by a prior systematic review conducted by the research team.12 This was used to explore participants' perceptions and experiences of the factors influencing ASRs' oral health behaviours and patterns of dental access. Participant views on optimal service design for ASRs were also explored. The interview guide is provided in online Supplementary File 1. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Transcripts were uploaded on NVivo 12 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2020). A reflective thematic analysis was conducted following Braun and Clarke's six steps19,20 and included: 1) familiarisation with the data; 2) data coding; 3) generation of initial themes; 4) reviewing and developing themes; 5) refining, defining and naming themes; and 6) writing the report. Thematic analysis provides a highly flexible approach that enables a researcher to identify and interpret patterns, or themes, in a set of data.19,20 It is also a particularly useful method for examining the perspectives of different participants, highlighting their similarities and differences, and subsequently leading to greater insight into the data.21

The analysis initially involved inductive coding under two headings: oral health behaviours and access. Two independent reviewers coded the data (MP, RB) to ensure credibility of findings and subsequently trustworthiness in analysis.21 During analysis, it became apparent that the emergent themes did not fit neatly within this dichotomy and often contributed to both outcomes of interest. It thus impaired the researcher's ability to iteratively and reflexively develop a nuanced understanding of concurrent, intertwining factors related to ASR oral care. Consequently, a second round of analysis was undertaken (MP, RB, HW) where coding and themes were generated, without any pre-defined grouping of data. Consideration was given on how our own characteristics, knowledge and experience may have influenced the analysis.15 Questions about how the coding was done, interpretation and the justification for decisions made, were discussed between the reviewers and agreements were reached by consensus. A number of stakeholders from diverse backgrounds (for example, dental, public health etc) (JD, SK, PJR, ES, JS, RW) had the opportunity to feed into the interpretation of the thematic analysis during phases 4-6 (reviewing, defining and naming themes and producing the report).

Ethical approval was obtained from the Faculty of Health Research Ethics and Integrity Committee, University of Plymouth (ref: 19/20-1189).

Results

Fourteen individuals were approached, of which twelve (four males and eight females) consented to participate in the study. Of the two people who did not take part, one was unable due to time constraints and the other one was on an extended leave and therefore unreachable at the time of the study.

Of the 12 participants who were interviewed, four were men and eight were women. Five of the participants were working in a dental setting (clinical dentistry, administration, community engagement, policy). One individual was from the Local Authority, three were employees at local community organisations providing immigration and other support to ASRs (including signposting to healthcare services) and the remaining three participants were from other healthcare backgrounds supporting ASRs with various health needs. All participants had knowledge and/or experience around the oral health care of ASRs. Two of the participants also had lived experience of forced displacement and the asylum process in the UK. Recruitment ceased when data saturation for the current focus of our study (that is, a range of [professional] stakeholders' perspectives from Plymouth) was reached.

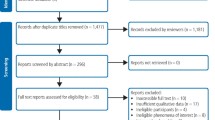

Reflexive thematic analysis identified six key themes that provided insight into factors hindering oral health care for ASRs and five themes that related to how oral health interventions, service delivery and accessibility could be improved for this group (Fig. 1). No differences between the male and female participants were observed. Themes relating to both oral heath behaviours and access are reported together because the insights relating to both are often intertwined. Each theme and their corresponding sub-themes are discussed in turn below. Participant quotes are identified using codes (P1, P2 etc).

Factors hindering oral care for ASRs

Prioritising safety and survival

Participants frequently emphasised that oral health may 'not [be] a priority' (P1) for ASRs until they 'are finally safe' (P2), both in terms of their living situation and asylum seeker case progression. Initially, the pressing urgency for ASRs will often be to achieve 'basic safety…and survival' (P4). A participant who had personal experience of living in a war-torn country effectively described how the precarious situation ASRs face can affect the importance they attribute to oral health care: 'dental health or oral hygiene is not a priority when you live in a camp…looking for safer places to live with your family. Picking up a toothbrush and brushing your teeth twice a day is something you will not even think about or consider' (P2). The 'length [and type] of journey' (P6) ASRs had experienced when trying to reach a place of safety was also reported as influential to their current self-oral care behaviours and attitudes towards accessing care. For example, 'they have to walk for weeks and weeks and then take trucks and then boats and then different ways to - to - to reach. So, throughout this journey, it is extremely difficult to maintain your oral health. So, whenever - when they have an issue, they will have to deal with it with like local solutions just to kill the pain and...and keep them going' (P8).

Once in the host country, other 'pressing priorities' (P3), such as, 'what is happening with my case?' (P10), 'where am I going to live? How am I going to get money for food?' (P1), take precedence over oral health. The presence of other health conditions may also render dentistry becoming of lower priority: 'what if you have other health pressures or conditions? [...] you might feel going to the dentist is an added pressure' (P4). All participants suggested that the main motivation for ASRs accessing dental services was pain; making it less likely for ASRs to seek routine dental care. Echoing previous comments about oral health becoming a priority for ASRs once safe, one participant acknowledged that 'now they're happy…not happy, but relatively settled and that major issue of being safe is finally achieved, things start to probably kick off in their head and one of them is the dental pain…this is when you start to hear from them' (P2). While some interviewees described alternative motivations among ASRs for dental access including routine check-ups and requesting a 'scale and polish' (P6), such experiences were rare.

Variations in cultural norms and practices

Variations in 'cultural practices and norms' (P7) were also reported as influential, with some ASRs reportedly perceiving their traditional methods, such as chewing sticks, as adequate oral hygiene aids.

Another influential cultural norm described was the taboo surrounding the expression of pain due to the perception that such expressions are indicative of weakness. Participants reported their own experiences and/or observations of how such cultural norms may affect how likely it is that men from certain groups would express both the presence of pain and the need for care, potentially delaying important treatment: 'very much it's…"yes I'm fine." I'm this strong young man. I can manage and I don't need any help' (P5). Cultural sensitivities to open discussion of certain health-related topics were also reported as a potential influence of care, as some translators may be reluctant in communicating crucial health-based questions (for example, around pregnancy).

Lack of knowledge about dental care

Two types of knowledge gaps were described by participants. Firstly, ASRs often reportedly have a lack of knowledge about oral self-care behaviours (for example, how to brush teeth properly) and of factors affecting oral health, for example, the impact of smoking and sugar consumption on oral health.

Secondly, participants identified a lack of patient and organisational awareness about 'where to go for services' and 'who to contact' (P0). For example: 'I don't think the NHS does a particularly good job of communicating out through local authorities and with organisations that support vulnerable groups. So, often organisations themselves don't know how to access dental services or how to signpost individuals to advise on oral health' (P7). This knowledge gap was reportedly being exacerbated by the limited 'availability of information in different languages' (P7). ASRs' lack of awareness that they needed to seek routine care was also reported, 'there is not enough education on people, to say you are required to have your teeth checked in this length of time' (P10).

Financial hardship and affordability of care

Cost was a recurrent theme relating to both oral health behaviours and accessing care, particularly for asylum seekers. Participants acknowledged that many ASRs are 'unable to have the luxury of choosing what to eat' when relying on 'helping organisations' that often provide 'food rations that are high-sugar based' (P2), or forced to choose 'foods that have long preserving lives because they can't afford' (P9) fresh fruit and vegetables. 'Access to resources such as a toothbrush and toothpaste' (P3) reiterated concerns of affordability and the perceived impact on oral health: 'I had the mother of a little girl who had seven teeth pulled out because she - they weren't looking after her teeth properly. And it was again this thing about trying to manage on a very small budget and buying food that wasn't really helpful' (P3). Such quotes highlight the complex relationship between affordability and oral health behaviours.

There were also concerns of treatment and transport affordability. At times, issues related to these were described simultaneously. For example, 'asylum support consists of £37 a week…they struggle to buy just the main things, they cannot afford to buy the tickets to go to the dentist, never mind paying for the treatment' (P6). Variability in the acceptance of HC2 certificates (that is, an NHS certificate allowing to get full help with healthcare expenses) led to contention and frustration. For example, one participant stated that some ASRs 'don't receive extensive dental treatment because of an inability to pay' (P10).

A gulf of understanding of what dental care would be like and experiences of it

Unmet expectations of dental care

Participants described a 'gulf in [ASRs'] understanding [of what dental care would be like] and experiences [of it]' (P4). In some instances, such discrepancies were due to patients and the dental team having different perceptions of what constitutes a course of treatment ('for them [asylum seekers] it's [extraction] not a treatment' [P6]) and different expectations of continuity of care: ('[expected there to be a] succession of follow-up appointments' (P12). ASRs' initial expectations were sometimes influenced by positive experiences of healthcare systems in their home country. However, for the majority of participants, discrepancies in expectations and experiences were most commonly described in relation to the speed in which people could be seen when in need: 'I think their expectations are that if you've got an emergency, you'll be seen quickly, but that's not always the case' (P1). Participants also reported that prior negative experiences, such as 'she went to the dentist…and had the wrong tooth pulled out!' (P12), affected trust and confidence in the profession, with people becoming reluctant to seek dental care: 'she had no faith in going back' (P12). Although less frequently acknowledged, the fear of the unknown also reportedly impeded the ability of ASRs to proactively seek care: 'they don't know what to expect when they come to see us, so it takes a while to build up that trust' (P11).

Re-creation of past trauma

Previous traumatic experiences, including torture, were reported as influencing ASRs' reactions to their dental care experiences, potentially impeding their ability to seek further care. A participant acknowledged that 'so many things in the environment in the dentist's surgery' (P9), such as the dentist wearing a mask, having to sit in a chair with your mouth open and listening to noises of drills may trigger 'some really traumatic memories' (P9).

Structures of dental services that leave vulnerable groups behind

Service access and availability

Service 'access' (P5) was considered 'extremely difficult' (P8) for ASRs, an experience also reported by the wider population. Existing funding structures and 'significant' waiting lists were considered to exacerbate the issue with 'the current NHS system', believed to be 'directed towards the general population…leaving behind the more vulnerable groups' (P7). Challenges in getting urgent appointments 'for people with infections and with swollen faces' (P6) were also raised.

Service location

For many participants, the physical location and limited number of dental practices providing emergency care was also described as problematic: 'there's only one location you can access urgent dental care services, so if you don't have transport, or you don't have money for transport, that can act as a primary barrier' (P7).

Punitive appointment booking systems

In addition, for some participants, the 'bureaucracy' and 'punitive' nature of appointment booking systems was also considered detrimental to dental access for ASRs: 'the way that these services are organised, you have to make a phone call very early in the morning and if you don't have access to a phone, or you have limited English, then it's very difficult to even make that call' (P7). Similarly, 'the actual route of access appears to be quite complex…almost punitive, like, "if you don't phone at this time, you've missed your chance". Not very flexible' (P4). Some participants acknowledged that the appointment booking system does not accommodate ASRs' transiency of lifestyle, for example, contact details often changing: 'so once someone moves on, if they're sending letters to people about, "you now can go and register at this dental practice", most of them aren't going to get that information' (P9) Perceived stigma and discrimination in obtaining appointments was also reported: 'I don't want to sound negative but there's also institutional racism in this part of the country because I'll tell you a story, a refugee called to make an appointment and has been rejected, they told him there is no appointment available for weeks and weeks. Same time, same place, same surgery, someone else with a clear British white person accent called and they got an appointment the next day…' (P8).

Lack and inappropriateness of translation services

Perhaps unsurprisingly, language was repeatedly described as a barrier to service access and delivery that applies to both dentists and ASRs. Difficulties described by participants included booking an appointment if English was not their first language, gaining consent and having limited access to 'interpretation services', or 'information in different languages' that may lead to 'a degree of apprehension, fear and frustration among dentists' (P7). The impact of such challenges should not be underestimated with some participants describing incidences, where 'people have been rejected because there was no available interpreter at that time' (P8), reiterating the disruptive and exclusionary impact communication services can present for both ASRs and healthcare professionals.

Ways to improve oral health interventions, service delivery and accessibility for ASRs

Participants described a number of strategies that could be used to improve oral health interventions, service delivery and accessibility for ASRs.

Accessible oral health education

One suggested strategy for enhancing oral care education was the embedding of oral health messages in ASRs' language courses with a clear focus on 'prevention' (P9), for example, providing details on 'what a good diet' (P4) might look like on a restricted budget. The importance of providing such information 'in different languages' (P12), supported by culturally diverse, 'appropriate and sensitive photographs, images and graphics' (P3) was also considered essential to the success of such a strategy.

Partnership working and creating supportive environments

Working in 'partnership with key organisations' (P1) and 'integrating oral health into the structure and processes that support ASRs' (P7) was considered integral in improving service design and accessibility.

Translators

Pairing patients with dentists who spoke the same language, providing face-to-face translator services that 'reduce time' (P8) and potential misunderstandings, and recording people's translator preferences to avoid any cultural barriers, eg women speaking to a male translator, were considered important steps by participants. Participants were keen to acknowledge that every effort should be made to ensure that 'the patient will be speaking directly with their own voice, in their own language' (P2).

Providing culturally sensitive and person-centred care

Training for healthcare professionals 'to help dentists understand the culture of the people they deal with' (P8) was considered paramount. Other suggestions made by participants for improving service provision for ASRs included developing meaningful relationships between patients and the dental teams, adopting a patient-centred approach to care delivery and service design, allocating more time when seeing ASR patients, improving awareness of service location and transportation, promoting outreach and community engagement activities and providing flexibility with appointment scheduling. Providing trauma informed care, which is underpinned by understanding of the impact of previous traumatic experiences (for example, torture) on a person's life and providing an environment where the person feels safe and can develop trust,22 was also recommended.

Incorporating ASRs' views into service design

Finally, when asked to consider whether a mainstream or dedicated service was most preferable for ASRs, participant opinion appeared divided. As shown in online Supplementary File 2, motivations for not having a dedicated service included trying to promote integration and inclusion. Conversely, justifications for having a dedicated service included ensuring cultural relevance, clinician skill and service accessibility. However, as suggested by several participants, it is perhaps best to ask 'people [ASRs] how they feel' (P5) about such a service design decision.

Other suggestions to improve service delivery and accessibility for ASRs are listed in online Supplementary File 3, with many suggestions often relying on sufficient funding and investment 'to tackle oral health inequalities' (P7).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in the UK to identify the factors influencing health-promoting behaviour activities and dental care access pertinent to ASRs. Some of the reported barriers are also experienced by the general population but to a lesser extent and by other vulnerable groups, such as those experiencing homelessness.23 Other factors, such as communication difficulties, are particularly unique to ASR communities. Adoption of the participants' suggested strategies for enhancing oral health interventions and service access and provision could help reduce inequalities and improve oral health outcomes for ASRs.

In line with available literature,24 language has been identified as a common barrier to oral health care, with participants in this research highlighting the need to ensure accurate and clear lines of communication between patients and the dental provider. Interviewees in this study unanimously agreed that provision of care by a dentist who speaks the same language is desirable, as is face-to-face translation (which may vary based on patient preference). However, the former appears incompatible with current NHS guidance that states professionals cannot act as interpreters unless they undergo a 12-week training course.25 Our findings highlight the need to revise interpretation protocols, or to at least explore how language support can be provided in a culturally appropriate and patient-centred manner.26 Even though evidence on the interpreters' role, trust and power in the dental setting is lacking, in general medical practice, the use of bilingual healthcare providers has been strongly advocated.26 Future research regarding the most efficient use of bilingual providers in the dental practice could enhance the provision of care for ASRs. As part of this work, it would be important to explore how relational issues in interpreter interactions can affect patient care and health27 and whether these experiences are shaped by the remote versus in-person consultation settings.

Limited and inequitable access to dental services among ASRs can perpetuate poor oral health and exacerbate inequalities. O' Donnell et al.,9 found that access to dental care for asylum seekers was more difficult and the experience less positive compared to medical care. Although access to NHS dentistry has become increasingly challenging for the general population, considering the compounding challenges of vulnerable groups in accessing care and their greater burden of disease, ensuring equitable access to health services is imperative.28,29,30 Suggestions both in the literature and our study for ensuring equitable access to dental and oral health services includes alternative commissioning arrangements, providing more public funding for dental services and identifying ways to provide services to vulnerable groups more efficiently.28,29,31 Other remedies for enhancing provision of care for ASRs identified in our study include multiagency collaboration, outreach work and promoting cultural awareness among dental teams. An understanding of the impact of previous torture and other forms of trauma on seeking and tolerating dental treatment is particularly important.28 Developing standards for dental professionals to provide trauma-informed care and better support victims of trauma and torture can foster a positive dental experience.

Notwithstanding the need to improve access to dental care, a re-orientation of dental services to enhance focus on prevention is also important to achieve sustainable improvements in oral health. Considering that ASRs are not a homogeneous group, reaching out and co-developing prevention programmes with members of the ASR community, charities and health providers is essential to ensure their accessibility and relevancy28 and empower ASRs to improve their oral health. Dental, dental therapy and dental nursing students and university community outreach programmes could aid the promotion of oral health messages and raise awareness, both among ASRs and support groups.

Undoubtedly, for both oral health promotion and provision of dental care, adopting a personalised approach, developing a trusting relationship between patients and dental teams and incorporating 'cultural competence' into practice, can optimise care quality. The definition of cultural competence by Betancourt et al.,32 'the ability of systems to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs and behaviours, including tailoring delivery to meet patients' social, cultural and linguistic needs' echoes our findings. Patient-centred dental care has also been described as an important tool in the clinical dental encounter.33,34 However, it is one that has not yet been fully realised or filtered down into practice.33 Investigation into how the NHS personalised care policy is implemented in the dental setting is warranted.35 The recently published advocacy guide by FDI World Dental Federation, Promoting oral health for refugees,36 provides valuable recommendations for improving oral health care for refugees across the globe.

This research advances existing knowledge and understanding. Multiple and diverse stakeholders participated in interpreting the results, thus offering diverse perspectives on possible themes. As interpretation of findings in qualitative research is prone to the researcher's subjectivity, such an approach minimised the potential of bias which may arise when having only one coder in qualitative data analysis. It also ensured credibility and increased confidence in our findings. Some limitations must be acknowledged. Although we interviewed a range of stakeholders, inclusion of refugees and/or the use of other qualitative methodologies could have enhanced our ability to triangulate the data. This could have provided an even more in-depth understanding of our phenomenon of interest. Furthermore, by interviewing commissioners, we could have obtained a greater insight into commissioning priorities of dental services for vulnerable groups. Nevertheless, two of our interviewees were themselves refugees who were also currently providing support to ASRs, hence some public representation was achieved.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study in the UK to identify the factors influencing oral health promotion and seeking behaviours among ASRs. Ensuring equitable access to health services and appropriate language support for this population group is important. Future research is needed to explore the views and experiences of ASRs of accessing and receiving care in the UK, as well as their recommendations on optimising oral health promotion and care provision.

References

The UN Refugee Agency. Global trends. Forced displacement in 2019. 2020. Available at https://www.unhcr.org/5ee200e37.pdf (accessed May 2022).

The UN Refugee Agency. Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. 2010. Available at https://www.unhcr.org/protection/basic/3b66c2aa10/convention-protocol-relating-status-refugees.html (accessed May 2022).

Freeman R, Doughty J, Macdonald M E, Muirhead V. Inclusion oral health: Advancing a theoretical framework for policy, research and practice. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2020; 48: 1-6.

Aspinall P J. Hidden Needs: Identifying Key Vulnerable Groups in Data Collections: Vulnerable Migrants, Gypsies and Travellers, Homeless People, and Sex Workers. 2014. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287805/vulnerable_groups_data_collections.pdf (accessed May 2022).

UK Government. Helping new refugees integrate into the UK: baseline data analysis from the Survey of New Refugees. 2010. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/116067/horr36-key-implications.pdf (accessed May 2022).

Joury E, Meer R, Chedid J C A, Shibly O. Burden of oral diseases and impact of protracted displacement: a cross-sectional study on Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. Br Dent J 2021; DOI: 10.1038/s41415-021-2960-9.

Davidson N, Skull S, Calache H, Murray S S, Chalmers J. Holes a plenty: oral health status a major issue for newly arrived refugees in Australia. Aust Dent J 2006; 51: 306-311.

Keboa M T, Hiles N, Macdonald M E. The oral health of refugees and asylum seekers: a scoping review. Global Health 2016; DOI: 10.1186/s12992-016-0200-x.

O'Donnell C A, Higgins M, Chauhan R, Mullen K. "They think we're OK and we know we're not". A qualitative study of asylum seekers' access, knowledge and views to health care in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res 2007; DOI: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-75.

Plymouth City Council. Asylum Seekers and Refugees Dental Health Care Needs. Discussion paper. 2019.

Public Health Wales.The Health Experiences of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Wales. 2019. Available at https://phwwhocc.co.uk/ih/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/PHW-Swansea-HEAR-technical-report-FINAL.pdf (accessed May 2022).

Paisi M, Baines R, Burns L et al. Barriers and facilitators to dental care access among asylum seekers and refugees in highly developed countries: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2020; DOI: 10.1186/s12903-020-01321-1.

Watt R G, Venturelli R, Daly B. Understanding and tackling oral health inequalities in vulnerable adult populations: from the margins to the mainstream. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 49-54.

Levesque J-F, Harris M F, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013; DOI: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18.

Geddis-Regan A R, Exley C, Taylor G D. Navigating the Dual Role of Clinician-Researcher in Qualitative Dental Research. JDR Clin Trans Res 2022; 7: 215-217.

Archer M. Critical Realism. London: Routledge, 2013.

Willig C. Perspectives on the epistemological bases for qualitative research. In Cooper H (ed) The Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. pp 1-17. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2012.

Cresswell J W, Plano Clark V L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Method Research. 2nd ed. California: Sage Publications, 2011.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77-101.

Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol 2021; 18: 328-352.

Nowell L S, Norris J M, White D E, Moules N J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int J Qual Methods 2017; 16: 1-13.

TheKing'sFund. Tackling poor health outcomes: the role of trauma-informed care. 2019. Available at https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2019/11/trauma-informed-care#comments-top (accessed September 2021).

Paisi M, Kay E, Plessas A et al. Barriers and enablers to accessing dental services for people experiencing homelessness: A systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2019; 47: 103-111.

Riggs E, Yelland J, Shankumar R, Kilpatrick N. 'We are all scared for the baby': promoting access to dental services for refugee background women during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016; DOI: 10.1186/s12884-015-0787-6.

NHS England. Guidance for commissioners: Interpreting and Translation Services in Primary Care. 2018. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/guidance-for-commissioners-interpreting-and-translation-services-in-primary-care.pdf (accessed May 2022).

Lehane D, Campion P. Interpreters: why should the NHS provide them? Br J Gen Pract 2018; 68: 564-565.

Brisset C, Leanza Y, Laforest K. Working with interpreters in health care: a systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. Patient Educ Couns 2013; 91: 131-140.

Fennell-Wells A V L, Yusuf H. Child refugees and asylum seekers: oral health and its place in the UK system. Br Dent J 2020; 228: 44-49.

Watt R G. COVID-19 is an opportunity for reform in dentistry. Lancet 2020; DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31529-4.

Watt R G, Daly B, Allison P et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet 2019; 394: 261-272.

El-Yousfi S, Jones K, White S, Marshman Z. A rapid review of barriers to oral healthcare for vulnerable people. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 143-151.

The Commonwealth Fund. Cultural Competence in Health Care: Emerging Frameworks and Practical Approaches. 2002. Available at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2002/oct/cultural-competence-health-care-emerging-frameworks-and (accessed May 2022).

Mills I, Frost J, Moles D R, Kay E. Patient-centred care in general dental practice: sound sense or soundbite? Br Dent J 2013; 215: 81-85.

Asimakopoulou K, Gupta A, Scambler S. Patient-centred care: barriers and opportunities in the dental surgery. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2014; 42: 603-610.

NHS England. What is personalised care? Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/what-is-personalised-care/ (accessed August 2021).

FDI World Dental Federation. Promoting oral health for refugees: an advocacy guide. 2020. Available at https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Promoting%20Oral%20Health%20for%20Refugees%20-%20An%20Advocacy%20Guide.pdf (accessed May 2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for taking part in the study.

Funding

The study was funded by Peninsula Dental Social Enterprise.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Martha Paisi: made substantial contributions to study conception and design and acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. Rebecca Baines: made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Hannah Wheat: made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Janine Doughty: made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Sarah Kaddour: made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Philip J. Radford: made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Eleftheria Stylianou: made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Jill Shawe: made substantial contributions to study conception and design. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Rob Witton: made substantial contributions to study conception and design. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paisi, M., Baines, R., Wheat, H. et al. Factors affecting oral health care for asylum seekers and refugees in England: a qualitative study of key stakeholders' perspectives and experiences. Br Dent J (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4340-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4340-5

This article is cited by

-

Facilitators and barriers to asylum seeker and refugee oral health care access: a qualitative systematic review

British Dental Journal (2024)

-

What factors influence refugees’ attendance to dental care services?

Evidence-Based Dentistry (2024)

-

What are the barriers faced by asylum seekers and refugees when accessing oral healthcare and do these barriers lead to a negative impact on oral health?

BDJ Team (2024)

-

Double burden of vulnerability for refugees: conceptualization and policy solutions for financial protection in Iran using systems thinking approach

Health Research Policy and Systems (2023)

-

Facilitators for increasing dental attendance of people from vulnerable groups: a rapid review of evidence relevant to the UK

British Dental Journal (2023)