Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is the receptor of COVID-19 pathogen SARS-CoV-2, but the transcription factors (TFs) that regulate the expression of the gene encoding ACE2 (ACE2) have not been systematically dissected. In this study we evaluated TFs that control ACE2 expression, and screened for small molecule compounds that could modulate ACE2 expression to block SARS-CoV-2 from entry into lung epithelial cells. By searching the online datasets we found that 24 TFs might be ACE2 regulators with signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) as the most significant one. In human normal lung tissues, the expression of ACE2 was positively correlated with phosphorylated Stat3 (p-Stat3). We demonstrated that Stat3 bound ACE2 promoter, and controlled its expression in 16HBE cells stimulated with interleukin 6 (IL-6). To screen for medicinal compounds that could modulate ACE2 expression, we conducted luciferase assay using HLF cells transfected with ACE2 promoter-luciferase constructs. Among the 64 compounds tested, 6-O-angeloylplenolin (6-OAP), a sesquiterpene lactone in Chinese medicinal herb Centipeda minima (CM), represented the most potent ACE2 repressor. 6-OAP (2.5 µM) inhibited the interaction between Stat3 protein and ACE2 promoter, thus suppressed ACE2 transcription. 6-OAP (1.25–5 µM) and its parental medicinal herb CM (0.125%–0.5%) dose-dependently downregulated ACE2 in 16HBE and Beas-2B cells; similar results were observed in the lung tissues of mice following administration of 6-OAP or CM for one month. In addition, 6-OAP/CM dose-dependently reduced IL-6 production and downregulated chemokines including CXCL13 and CX3CL1 in 16HBE cells. Moreover, we found that 6-OAP/CM inhibited the entry of SARS-CoV-2 S protein pseudovirus into target cells. These results suggest that 6-OAP/CM are ACE2 inhibitors that may potentially protect lung epithelial cells from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the pathogen of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), enters the airway epithelial cells by using its Spike (S) glycoprotein to bind its receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on human target cells [1,2,3]. The S protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that is cleaved into S1 and S2 subunits during viral infection [4], and the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein harbors a Furin cleavage site at the boundary between the S1/S2 subunits [5,6,7]. SARS-CoV-2 uses the cellular transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2 for S protein priming [3]. The S1 subunit contains an RBD that can directly bind the peptidase domain (PD) of ACE2, whereas the S2 subunit is responsible for membrane fusion [8]. On the other hand, ACE2 has an N terminal PD and a C-terminal collectrin-like domain (CLD) that ends with a single transmembrane helix [9]. Cleavage of the C-terminal segment of ACE2 by TMPRSS2 enhances the S protein–driven viral entry [8]. Cryo-EM structure shows that the SARS-CoV-2 S protein binds at least 10 times more tightly than the corresponding S protein of SARS–CoV to ACE2 [4].

The ACE2 gene localizes on the chromosome Xp22 [10], and its expression is modulated by epigenetic mechanisms including histone methylation [11], histone acetylation [12], and microRNAs [13]. The enhancer of Zeste Homologue 2 (EZH2) inhibits ACE2 expression by induction of H3K27me3 at ACE2 promoter [11], whereas histone acetyltransferase-1 (HAT1), histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2), and lysine demethylase 5B (KDM5B) play roles in regulating ACE2 expression [14]. The NADC-dependent deacetylase silent information regulator 2 homolog 1 (SIRT1) binds to ACE2 promoter to facilitate its transcription during cellular energy stress [12]. Chromatin remodeler Brahma-related gene-1 (Brg1) and transcription factor (TF) forkhead box M1 (FoxM1) cooperate within the endothelium to control cardiac ACE2 and ACE expression [15]. ACE2 is shown to be an interferon-stimulated gene [16]. At protein level, ACE2 is regulated by glycosylation and phosphorylation [17]. We found that ACE2 undergoes ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation with S-phase kinase associated protein 2 (Skp2) as an E3 ligase [18]. The murine double minute 2 (MDM2) also plays a role in ACE2 degradation [19]. However, the mechanisms of ACE2 regulation remain to be scrutinized, which may facilitate the development of pharmacological modulation of ACE2 to combat COVID-19 and other related diseases.

In this study, we systematically evaluated TFs that can control ACE2 expression, and screened for small compounds that are able to modulate ACE2 expression level to block SARS-CoV-2 from entry into lung epithelial cells. We found that the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is an ACE2 regulator, and a small compound 6-O-angeloylplenolin (6-OAP; also known as brevilin A) as well as its parental medicinal herb Centipeda minima (CM) extract, in which 6-OAP was one of the most abundant sesquiterpene lactones [20], inhibited the entry of SARS-CoV-2 S protein pseuduovirions into lung epithelial cells.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Institute and Hospital. All samples were collected with informed consent. The lung biopsy samples of 12 patients with benign diseases such as pulmonary chronic inflammation (Supplementary Table S1), were collected from the Department of Pathology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay was performed using an anti-ACE2 and an anti-phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) antibodies. Fresh normal lung tissues (5 cm away from tumor lesions) were collected from 49 treatment-naive patients with lung adenocarcinoma (Supplementary Table S2), lysed, and analyzed by Western blot for the expression of ACE2 and pSTAT3.

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies used in Western blotting were as follows: rabbit monoclonal anti-human ACE2 (#ab108252, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; 1:1000 for Western blot); rabbit polyclonal anti-human ACE2 (#4355, 1:1000), mouse anti-STAT3 (#9139 S, 1:1000), rabbit anti-phospho-STAT3 (#9145 S, 1:2000), anti-GAPDH (#5174, 1:1000) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; anti-Actin (#A5441, 1:5000) was purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; rabbit monoclonal anti-human ACE2 (#ab108252, Abcam; 1:200) and mouse anti-phospho-STAT3 (#9145S, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:200) were used in IHC assay. 6-OAP was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, and medicinal plant CM was bought from Beijing Tong Ren Tang Group (Beijing, China). For preparation of CM, the herb (30 g) was soaked in 400 mL water for 30 min, decocted with strong fire to boiling for 15 min and then simmered for 20 min. The decoction was centrifuged to remove insoluble ingredients and filtered with a 0.22 µm pore-size filter, and the sterilized CM was aliquoted and stored at −30 °C.

Cell culture and transfection

The human normal bronchial epithelial 16HBE (Clonetics, Walkersville, MD, USA) and Beas-2B (the American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) cells, human embryonic lung fibroblast HLF cells (Kenqiang Instrument Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), and human embryonic kidney HEK-293 cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM or RPMI-1640 (Gibco/BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco/BRL). The cells were transfected with 50 nM double-stranded siRNA oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table S3) using Lipofectamine 3000 kit (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD, USA), or treated with 6-OAP, CM, or compounds from other medicinal herbs (Supplementary Table S4) for 48 h. The cells were lysed and tested by assays described below.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

For ChIP, the cells were treated or untreated with 6-OAP, harvested and fixed with formaldehyde. The DNA was sheared into small, uniform fragments using sonication, and specific protein/DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated using an antibody against Stat3 (#9139S, Cell Signaling Technology). Following immunoprecipitation, cross-linking was reversed, the proteins were removed by treatment with proteinase K, and the DNA was purified and analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR). For qRT-PCR, the cells were harvested, and the total RNA was isolated with the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Total RNA (2 μg) was annealed with random primers at 65 °C for 5 min. The cDNA was synthesized using a 1st-STRAND cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Premix ExTaq™ (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China) and primers listed in Supplementary Table S3.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and luciferase assay

The DNA-binding activity of Stat3 was assayed using a LightShift Chemiluminescent Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay kit (Viagene Biotech Inc., Tampa, FL, USA) according to manufacturer’s instruction, and the biotin-labeled Stat3 binding site (5′-Biotin-TTACAGTAACATTTCAACCTTTTCTTC-3′) was used as target DNA. The biotin-labeled GATA1 binding DNA (5’-Biotin-CACTTGATAACAGAAAGTGATAACTCT-3’) was used as a positive control. For luciferase assays, cells were transfected with pGL3-ACE2-luciferase constructs, treated with compounds for 24–48 h, and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Western blotting

The cells and lung specimens were lysed on ice for 30 min in RIPA buffer [18] and protein extracts were quantitated. The proteins were loaded on 8%–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel, electrophoresed, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated with primary antibody, washed, incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), and detected with Luminescent Image Analyzer LSA 4000 (GE, Fairfield, CO, USA). Densitometry analyses of immunoblot bands were employed to quantitate the expression level of the proteins.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis

The formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens were deparaffinized and underwent a heat-induced epitope retrieval step [18]. The sections were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min and incubated with anti-ACE2/anti-phospho-STAT3 antibodies at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 90 min at 37 °C. Detection was performed with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Zhongshan Golden Bridge, Beijing, China) and the immunoreactivity score (IRS) was evaluated as previous described [21].

SARS-CoV-2 S protein pseudovirions

Pseudovirions were purchased from Sino Biological Inc. (Beijing, China), and were prepared by transfection of 293 T cells with psPAX2, pLenti-GFP, and plasmids encoding SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein using polyetherimide [18]. To test the infection activity, 16HBE and 293T-ACE2 cells were seeded onto 96-well plates, pre-treated with 6-OAP and CM at the indicated concentration, followed by co-incubation with 100 μL culture media containing pseudovirions for 48 h. The cells were lysed with 60 μL 1×Lysis buffer (Promega) and evaluated by quantification of the luciferase activity using a Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Animals

The animal studies were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Institute and Hospital, and the experiments followed the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals. Five to six weeks old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China), and kept in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment. The mice were treated with 6-OAP (50 mg·kg−1·d−1) or CM (0.5% solution 200 µL/day) for 30–60 days, and the expression of STAT3 and ACE2 was evaluated by Western blot assays.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistically significant differences between data groups were evaluated by Student’s t test or Fisher’s exact test, and the correlation between relative ACE2 and STAT3 expression levels was measured by Spearman correlation analysis. P < 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant in all cases.

Results

Transcription factors that can regulate ACE2 expression

The Cistrome Data Browser (DB) that is a resource derived from chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq), DNase I hypersensitive site sequencing (DNase-seq) and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) chromatin profiling assays [22], were employed to uncover TFs that control the expression of ACE2. We found that 24 TFs, which have a regulatory potential (RP) value of 0.3 or greater in at least 2 cell lines, could be TFs that control ACE2 expression. These included HOXB13, CHAT, MAFK, TET3, CEBPB, Stat3, and others (Fig. 1a). We evaluated the potential relationship between ACE2 and the 24 TFs using the RNA-Seq data of non-cancer samples in the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) [23], which contains datasets of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [24] and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) [25]. We found that while some TFs were positively or negatively associated with ACE2 expression level (Fig. 1b), Stat3 was the most significant TF gene that associated with ACE2 expression with a high R and a low P values (Fig. 1c).

a Putative transcription factors of ACE2 predicted by Cistrome Data Browser. Each dot represents a ChIP-seq sample and the top 24 factors that ranked by the regulatory potential score over all ChIP-seq samples are shown. b, c Association between ACE2 and the representative transcription factors (b) including STAT3 (c) was analyzed using the RNA-Seq data of non-cancer samples in the GEPIA dataset.

The expression of ACE2 is positively associated with phosphorylated Stat3 in human lung tissues

We tested the association between the expression of ACE2 and the active form of Stat3, the phosphorylated Stat3 (p-Stat3), in lung biopsy samples of 12 patients with benign disease such as pulmonary chronic inflammation (Supplementary Table S1). By IHC assay, we found that 6 (50%) of 12 cases had high ACE2 expression, in whose samples the expression of p-Stat3 was also high (Fig. 2a, b). In the other 6 patients whose ACE2 was low, the p-Stat3 was also low (Fig. 2a, b). In normal lung tissues of patients with lung cancer, p-Stat3 was high in patients with high level of ACE2 detected by Western blot assays (Fig. 2c). Densitometry analysis of Western blot bands showed that ACE2 expression level was positively associated with p-Stat3 expression (P = 0.01; Fig. 2d). We therefore investigated the mechanism of action of STAT3 in regulating ACE2 in lung epithelial cells.

a, b Immunohistochemical staining experiments were performed in 12 patients with benign disease using anti-ACE2 and anti-phospho-Stat3 antibodies (a), and the immunoreactivity score was evaluated (b). Scale bars, 50 μm. *P < 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test. c Western blot assays were performed in 49 normal lung tissues isolated from patients with lung cancer at surgery. d The relative ACE2 and p-Stat3 levels were determined by densitometry analysis of immunoblot bands and normalized to Actin, and the potential association between ACE2 and p-Stat3 levels was analyzed.

ACE2 is a target gene of Stat3

By analyzing the promoter sequence of ACE2, we found a Stat3-binding site, TTCAACCTTTT, locates at 874 bp upstream of the transcription start site (Fig. 3a). By EMSA, we showed that at the presence of interleukin-6 (IL-6), biotin-labeled Stat3-binding (BD) DNA formed complex with Stat3 protein (Fig. 3b). In 16HBE cells, silencing of Stat3 by siRNAs significantly downregulated ACE2 expression (Fig. 3c), whereas exogenous Stat3 significantly upregulated ACE2 level (Fig. 3d). At protein level, we found that knockdown of Stat3 by siStat3-1 and siStat3-2 led to downregulation of ACE2 in 16HBE cells (Fig. 3e). In this cell line, overexpression of Stat3 by transfection of Flag-Stat3 plasmids into the cells resulted in increased expression of Stat3, p-Stat3, and ACE2 (Fig. 3f). In 16HBE cells starved for serum for 6 h, treatment with IL-6 at 50 ng/mL for 30 min caused upregulation of p-Stat3 and ACE2 at protein level (Fig. 3g). In 293 T cells, silencing of Stat3 by siStat3 led to downregulation of ACE2 (Fig. 3h), whereas increase in Stat3 by transfection of Flag-Stat3 plasmids resulted in increase of ACE2 (Fig. 3i). These results indicate that Stat3 represents an important TF that controls ACE2 expression.

a The Stat3 binding site of ACE2 promoter. TSS, transcription start site. b EMSA using Stat3 protein and biotin-labeled Stat3-binding (BD) DNA in the presence or absence of IL-6. Biotin-labeled GATA1-BD DNA or unlabeled Stat3-BD DNA was used as controls. IL-6, interleukin-6. c, d Relative mRNA levels of Stat3 and ACE2 in 16HBE cells transfected with siStat3 (c) or Flag-Stat3 (d), measured by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3 for biological independent replicates. *P < 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test. e, f Western blot analyses of ACE2 in 16HBE cells transfected with siStat3 (e) or Flag-Stat3 (f). g 16HBE cells were treated with IL-6 at 50 ng/mL for 30 min, lysed, and subjected to Western blot using indicated antibodies. h, i Western blot analyses of ACE2 in 293 T cells transfected with siStat3 (h) or Flag-Stat3 (i).

Screening for medicinal compounds that can modulate ACE2 expression

ACE2 has rapidly emerged as a specific target for COVID-19 treatment [17], and natural products used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) represent a wealthy source for the identification of novel therapeutic compounds against SARS-CoV-2 [26]. To screen for TCM herbal compounds that can suppress ACE2 expression, ACE2 promoter-luciferase constructs were transfected into HLF cells and luciferase assays were performed. We found that among the 64 compounds (Supplementary Table S4) tested, 8 (12.5%) compounds were able to upregulate ACE2 (relative luciferase expression level >1.5 as compared with negative controls) and 16 (25.0%) compounds could downregulate ACE2 (relative luciferase expression level <0.5 as compared with negative controls) (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, we found that 6-OAP that can suppress Stat3 [27], exhibited the most potent inhibitory activity on ACE2 expression (Fig. 4a).

a HLF cells were transfected with ACE2 promoter-luciferase constructs and treated with 64 compounds and negative controls, and the luciferase activity was measured. b Luciferase activity was detected in ACE2 promoter-luciferase-expressing HLF cells that were treated with 6-OAP at 2.5 µM for 24–48 h. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3 for biological independent replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, two-tailed Student’s t-test. c A chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed in 6-OAP treated or untreated 16HBE cells, and STAT3-bound ACE2 expression level was detected by quantitative PCR. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3 for biological independent replicates. **P < 0.01, two-tailed Student’s t-test. d EMSA using Stat3 protein and biotin-labeled Stat3-BD DNA in the presence of IL-6 and/or 6-OAP. e, f The ACE2 promoter-luciferase in 16HBE cells transfected with siStat3 (e) or Flag-Stat3 (f), in the presence of absence of 6-OAP. *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA. g The luciferase activity of HLF cells driven by wild-type or mutant ACE2 promoter in the presence or absence of 6-OAP. *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

The effect of 6-OAP on ACE2 expression was further verified, in that treatment of HLF cells expressing ACE2 promoter-luciferase with 6-OAP at 2.5 µM for 24–48 h significantly inhibited the luciferase activity (Fig. 4b). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-quantitative PCR (qPCR) was employed, and the results showed that while Stat3 was able to bind ACE2 promoter, 6-OAP significantly suppressed the binding affinity between Stat3 and ACE2 promoter (Fig. 4c). In an EMSA experiment, IL-6 treatment enhanced the interaction between Stat3 and biotin-labeled ACE2 promoter DNA, which was inhibited by 6-OAP (Fig. 4d). In these cells, silencing of Stat3 by Stat3-specific siRNA significantly repressed the luciferase activity driven by ACE2 promoter, whereas 6-OAP potentiated this effect (Fig. 4e). On the contrary, ectopic expression of Stat3 significantly upregulated ACE2 promoter-driven luciferase activity, which was suppressed by 6-OAP (Fig. 4f). Moreover, while 6-OAP inhibited luciferase activity driven by wild-type ACE2 promoter, it failed to repress luciferase activity driven by mutant ACE2 promoter in which the Stat3-binding site was deleted (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Table S3). These results indicated that 6-OAP inhibits ACE2 via suppression of Stat3.

6-OAP and CM downregulate ACE2 in vitro and in vivo

We next tested the effects of 6-OAP on the expression of ACE2 at protein level, and found that this compound induced downregulation of ACE2 in a dose- and time-dependent manner in 16HBE and Beas-2B cells (Fig. 5a–c). In 16HBE cells, IL-6 upregulated p-Stat3 and ACE2, whereas 6-OAP downregulated ACE2 and antagonized IL-6’s effect (Fig. 5d). Previously, 6-OAP was identified as one of the most abundant sesquiterpene lactones extracted from medicinal herb CM [20]. We showed that treatment of the 16HBE and Beas-2B cells with CM at 0.125%-0.5% also induced downregulation of ACE2 in dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 5e–g).

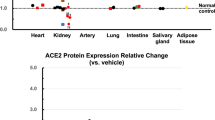

a, b Western blot assays using lysates of 16HBE cells treated with 6-OAP at indicated concentrations and time points. c Western blot assays using lysates of Beas-2B cells upon 6-OAP treatment. d 16HBE cells were treated with 6-OAP and/or IL-6, lysed, and subjected to Western blot. e, f 16HBE cells were treated with CM at indicated concentrations and indicated time points, lysed, and subjected to Western blot assays using indicated antibodies. CM, Centipeda minima. g Beas-2B cells were treated with CM, lysed, and subjected to Western blot. h C57BL/6 mice were treated with 6-OAP or CM for one month, sacrificed, and lung tissues were isolated and lysed for Western blot analyses using anti-ACE2 and anti-p-Stat3 antibodies. i The relative ACE2 and p-Stat3 expression levels were determined by densitometry analysis of immunoblot bands and normalized to Actin. *P < 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test. j C57BL/6 mice were treated with CM for two months, sacrificed, and lung tissues were isolated and lysed for Western blot analyses. k The relative ACE2 and p-Stat3 expression levels were determined by densitometry analysis of immunoblot bands and normalized to Actin. **P < 0.01, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To test the in vivo effects of 6-OAP and CM on ACE2 expression, C57BL/6 mice were treated with the agents for one months. We showed that treatment of the mice with 6-OAP at 50 mg·kg−1·d−1 or 0.5% CM solution (100 µL) per day for 30 days significantly downregulated ACE2 and p-Stat3 expression in the lung tissues (Fig. 5h, i). To further verify the in vivo effect, the 0.5% CM solution (100 µL) treatment schedule was extended to 60 days, and the lung tissues of the mice were isolated. We showed that upon CM treatment, the expression of ACE2 and p-Stat3 was significantly repressed (Fig. 5j, k). These results indicated that the compound 6-OAP and medicinal herb CM downregulate ACE2 expression in vitro and in vivo.

6-OAP and CM reduce the expression of cytokines/chemokines and inhibit SARS-CoV-2 S protein pseudovirus cell entry

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS), the uncontrolled release of cytokines triggered by SARS-CoV-2, is a life-threatening toxicity that may lead to detrimental effects such as leakage from capillaries, tissue toxicity and edema, organ failure, and shock [28]. Studies showed that calprotectin S100A8/S100A9, CX3CL1, CXCL11, CXCL13 and IL-6 may play a key role in CRS of COVID-19 [29, 30]. We thus tested the effects of 6-OAP and CM on the expression levels of these cytokines/chemokines, and found that the expression of IFNA2, CXCL13, CX3CL1, CXCL11, but not calprotectin genes S100A8/S100A9 was markedly reduced after CM and 6-OAP treatment (Fig. 6a, b). Furthermore, we found that 16-HBE cells were able to produce IL-6 and 6-OAP could reduce the concentration of IL-6 in supernatants of the cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6c).

a, b Relative mRNA levels of indicated genes in 16HBE cells that were treated with CM (a) or 6-OAP (b) for 48 h. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3 for biological independent replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-tailed Student’s t-test. c IL-6 levels in 16HBE cell supernatants were measured by ELISA. Data are represented as means ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test. d, e The effects of 6-OAP (5 µM)/CM (0.5%) on SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein pseudovirus entry into 16HBE (d) and 293T-ACE2 (e) cells, revealed by relative luciferase activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, two-tailed Student’s t-test. f Schematic representation of the mechanisms of the action of 6-OAP/CM in modulation of Stat3 and ACE2.

The effects of 6-OAP/CM on viral entry were tested in 16HBE cells using the SARS-CoV-2 S protein pseudovirus [31] and the results showed that while the pseudovirion was able to enter into the cells, treatment with 6-OAP/CM at 5 µM or 0.5% for 48 h reduced the entry of pseudovirus by approximately 42% and 44%, respectively, revealed by relative luciferase activity (Fig. 6d). Similarly, 6-OAP (5 µM) and CM (0.5%) also inhibited SARS-CoV-2 S protein pseudovirus entry into the 293T-ACE2 cells by 19% and 23%, respectively (Fig. 6e). These results suggested that 6-OAP and CM could inhibit the cytokine/chemokines production and block SARS-CoV-2 S protein pseudovirus entry into target cells.

Discussion

The application of TCM has an important role in China’s containment of COVID-19 [26, 32]. Current findings have shown that TCM can reduce the incidence of viral infections, ameliorate immune dysregulation, alleviate the inflammatory response, and suppress lung injury and fibrosis, though the mechanisms of action remain unclear [32, 33]. Here, we showed that a medicinal herb CM and its main component 6-OAP substantially inhibited the expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 at both mRNA and protein levels through suppression of STAT3 and thus preventing the virus entry into lung epithelium cells. CM is a Compositae plant distributing over East and South Asia and Oceania, and has been used for the treatment of headache, cough, expectoration, nasal allergy, diarrhea, malaria, and asthma in China and Korea, suggesting the potential application of CM in treating COVID-19 (Fig. 6f).

Blocking the virus from entering into the cells is a direct mean to combat SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 has rapidly emerged as an attractive target for COVID-19 treatment [3]. Furthermore, the recombinant soluble ACE2 (hrsACE2) can reduce cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 by competing with endogenous ACE2 and its efficacy is being evaluated in phase 2 trials as an approach for SARS-CoV-2 infection treatment [34]. Despite the rapid advances in the understanding of physiological and pathological roles of ACE2, the mechanisms affecting its expression remain to be investigated [8]. Recently, it is reported that in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and severe osteoarthritis, ACE2 is upregulated in synovium tissues and is likely maintained by IL-6/STAT3-mediated stimulation [35]. However, another study indicated that the two STAT3 alternatively spliced isoforms affect the expression of ACE2 differently in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7, i.e., the major type STAT3α decreases ACE2 mRNA and protein expression whereas another transcript variant STAT3β causes opposite effect [36]. Our results indicated that Stat3 could directly bind to the promoter of ACE2 and enhance its transcription. Because perturbation of Stat3 partially modulating ACE2 expression, other TFs may also play a role in regulating this gene.

While attempting to vaccinate the world’s population, the continually emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 have negatively affected the efficacy of vaccines [37]. The newly Omicron variant (BA.1/B.1.1.529), which is currently dominating the epidemic, harbors 36 mutations in the neutralizing antibodies that target S protein, including 15 within the RBD region and links to increased infectivity and the ability to evade vaccine-induced humoral immunity [38]. Since the mutations in the host ACE2 are rare, strategies for blocking ACE2 are considered a potential drug development strategy [39]. Anti-hypertension drugs including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been used to prevent and treat COVID-19 [40], and routine use of ACEIs and ARBs in hypertension was not associated with the infection risk or mortality or severe disease of COVID-19 [41,42,43]. There is a lack of an association between chronic receipt of renin-angiotensin system antagonists and severe outcomes of COVID-19 [44]. Our results indicated that the herbal medicine CM and its extract component 6-OAP reduced the expression of ACE2 and blocked S protein-mediated SARS-CoV-2 pseudovious entry into lung epithelial cell, suggesting that this ancient remedy may have potentials in fighting the pandemic.

CRS is common in patients with COVID-19, and elevated serum IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory cytokines correlate with respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and are hallmarks of severely ill patients [29, 30]. Given the pathophysiology of cytokine-driven hyperinflammatory syndromes, IL-6–IL-6R antagonists are recommended as one of the promising options available to severe COVID-19 [29]. IL-6 receptor antibodies tocilizumab and sarilumab have been used in treating the disease, and beneficial effects were seen in some severely or critically ill COVID-19 patients (though the efficacies were minor in some patients) [45,46,47]. In this study, we found that CM/6-OAP was able to inhibit the production of IL-6 and a few other cytokines/chemokines, possibly through suppression of STAT3, suggesting the immune-modulatory role of CM/6-OAP in treating CRS.

In conclusion, we systematically screened for TFs that can regulate ACE2 and small compounds that could modulate ACE2 expression, and found that 6-OAP and its parental herb CM reduced ACE2 expression and blocked SARS-CoV-2 S protein pseuduovirions infection through suppression of TF STAT3. CM/6-OAP reduced production of IL-6 and inhibited the expression of CXCL13 and CX3CL1 that are important for CRS (Fig. 6f). Since CM has been used for a long history in treating benign diseases including cough, expectoration, nasal allergy, diarrhea, malaria, and asthma in China and Korea [48], clinical trials could be conducted to test the efficacy of CM/6-OAP in combination with standard treatments in COVID-19.

References

Gheblawi M, Wang K, Viveiros A, Nguyen Q, Zhong JC, Turner AJ, et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system: Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Discovery of ACE2. Circ Res. 2020;126:1456–74.

Zou X, Chen K, Zou J, Han P, Hao J, Han Z. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front Med. 2020;14:185–92.

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–80.e8.

Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–3.

Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–92.e6.

Wu C, Zheng M, Yang Y, Gu X, Yang K, Li M, et al. Furin: A potential therapeutic target for COVID-19. iScience. 2020;23:101642.

Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020;26:450–2.

Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444–8.

Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res. 2000;87:E1–9.

Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme: Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33238–43.

Li Y, Li H, Zhou L. EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 inhibits ACE2 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;526:947–52.

Clarke Nicola E, Belyaev Nikolai D, Lambert Daniel W, Turner Anthony J. Epigenetic regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) by SIRT1 under conditions of cell energy stress. Clin Sci. 2013;126:507–16.

Lambert Daniel W, Lambert Louise A, Clarke Nicola E, Hooper NM, Porter Karen E, Turner Anthony J. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is subject to post-transcriptional regulation by miR-421. Clin Sci. 2014;127:243–9.

Pinto BGG, Oliveira AER, Singh Y, Jimenez L, Gonçalves ANA, Ogava RLT, et al. ACE2 expression is increased in the lungs of patients with comorbidities associated with severe COVID-19. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:556–63.

Yang J, Feng X, Zhou Q, Cheng W, Shang C, Han P, et al. Pathological Ace2-to-Ace enzyme switch in the stressed heart is transcriptionally controlled by the endothelial Brg1–FoxM1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E5628–E35.

Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, Mbano IM, Miao VN, Tzouanas CN, et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020;181:1016–35 e19.

Saponaro F, Rutigliano G, Sestito S, Bandini L, Storti B, Bizzarri R, et al. ACE2 in the Era of SARS-CoV-2: Controversies and novel perspectives. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:588618.

Wang G, Zhao Q, Zhang H, Liang F, Zhang C, Wang J, et al. Degradation of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Skp2 in lung epithelial cells. Front Med. 2021;15:252–63.

Shen H, Zhang J, Wang C, Jain PP, Xiong M, Shi X, et al. MDM2-mediated ubiquitination of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 contributes to the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2020;142:1190–204.

Ding LF, Liu Y, Liang HX, Liu DP, Zhou GB, Cheng YX. Two new terpene glucosides and antitumor agents from Centipeda minima. J Asian Nat Products Res. 2009;11:732–6.

Remmele W, Stegner HE. Recommendation for uniform definition of an immunoreactive score (IRS) for immunohistochemical estrogen receptor detection (ER-ICA) in breast cancer tissue. Pathologe. 1987;8:138–40.

Zheng R, Wan C, Mei S, Qin Q, Wu Q, Sun H, et al. Cistrome Data Browser: Expanded datasets and new tools for gene regulatory analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:D729–D35.

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C, Zhang Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W98–W102.

Chang K, Creighton CJ, Davis C, Donehower L, Drummond J, Wheeler D, et al. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1113–20.

The GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: Multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–60.

Chen K, Chen H. Traditional Chinese medicine for combating COVID-19. Front Med. 2020;14:529–32.

Cheng X, Liu YQ, Wang GZ, Yang LN, Lu YZ, Li XC, et al. Proteomic identification of the oncoprotein STAT3 as a target of a novel Skp1 inhibitor. Oncotarget. 2017;8:2681–93.

Zhou G, Chen S, Chen Z. Advances in COVID-19: The virus, the pathogenesis, and evidence-based control and therapeutic strategies. Front Med. 2020;14:117–25.

Moore JB, June CH. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science. 2020;368:473–4.

Silvin A, Chapuis N, Dunsmore G, Goubet AG, Dubuisson A, Derosa L, et al. Elevated calprotectin and abnormal myeloid cell subsets discriminate severe from mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;182:1401–18.e18.

Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L, et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1620.

Li L, Wu Y, Wang J, Yan H, Lu J, Wan Y, et al. Potential treatment of COVID-19 with traditional chinese medicine: What herbs can help win the battle with SARS-CoV-2? Engineering (Beijing, China) 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.08.020. Online ahead of print.

Ni L, Wen Z, Hu W, Tang W, Wang H, Zhou L, et al. Effects of Shuanghuanglian oral liquids on patients with COVID-19: A randomized, open-label, parallel-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Front Med 2021: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11684-021-0853-6.

Monteil V, Kwon H, Prado P, Hagelkrüys A, Wimmer RA, Stahl M, et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:905–13.e7.

Mokuda S, Tokunaga T, Masumoto J, Sugiyama E. Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2, a SARS-CoV-2 receptor, is upregulated by Interleukin 6 through STAT3 signaling in synovial tissues. J Rheumatol. 2020;47:1593–5.

Shamir I, Abutbul-Amitai M, Abbas-Egbariya H, Pasmanik-Chor M, Paret G, Nevo-Caspi Y. STAT3 isoforms differentially affect ACE2 expression: A potential target for COVID-19 therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:12864–8.

Callaway E. Heavily mutated Omicron variant puts scientists on alert. Nature. 2021;600:21.

Garcia-Beltran WF, St Denis KJ, Hoelzemer A, Lam EC, Nitido AD, Sheehan ML, et al. mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell. 2022;185:457–66.

Zanganeh S, Goodarzi N, Doroudian M, Movahed E. Potential COVID-19 therapeutic approaches targeting angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; An updated review. Rev Med Virol. 2021:e2321. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2321. Online ahead of print.

Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111:2605–10.

Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M, Apolone G, Corrao G. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers and the risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2431–40.

Fosbøl EL, Butt JH, Østergaard L, Andersson C, Selmer C, Kragholm K, et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use with COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality. JAMA. 2020;324:168–77.

Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, Troxel AB, Iturrate E, Johnson SB, et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2441–8.

Jiuyang Xu, Chaolin H, Guohui F, Zhibo L, Lianhan S, Fei Z, et al. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers in context of COVID-19 outbreak: A retrospective analysis. Front Med. 2020;14:601–12.

Soin AS, Kumar K, Choudhary NS, Sharma P, Mehta Y, Kataria S, et al. Tocilizumab plus standard care versus standard care in patients in India with moderate to severe COVID-19-associated cytokine release syndrome (COVINTOC): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respiratory Med. 2021;9:511–21.

Lescure FX, Honda H, Fowler RA, Lazar JS, Shi G, Wung P, et al. Sarilumab in patients admitted to hospital with severe or critical COVID-19: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respiratory Med. 2021;9:522–32.

Wang D, Fu B, Peng Z, Yang D, Han M, Li M, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with moderate or severe COVID-19: A randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter trial. Front Med. 2021;15:486–94.

Taylor RS, Towers GH. Antibacterial constituents of the Nepalese medicinal herb, Centipeda minima. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:631–4.

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81830093), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2020YFA0803300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672765, 81802796, and 82073092), and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS; Nos. 2021-RC310-003, 2020-RC310-002, 2019RC310002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GBZ and GZW conceived the study and designed the experiments. GZW, LJL, DW, HY, JW, HZ, BBS, FYY, ZW, and DWX performed the experiments. JW, HZ, REF, and KFX harvested/provided biospecimens/materials. GBZ wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Lj., Wang, D., Yu, H. et al. Transcriptional regulation and small compound targeting of ACE2 in lung epithelial cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 43, 2895–2904 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-022-00906-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-022-00906-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

ACE2 in chronic disease and COVID-19: gene regulation and post-translational modification

Journal of Biomedical Science (2023)