Abstract

We aim to assess physicians’ level of resilience and define factors that improve or decrease the resilience level during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physicians from hospitals located in areas with different COVID-19 caseload levels, were invited to participate in a national e-survey between April and May 2020. Study participants were mainly emergency physicians, and anaesthesiologists, infectious disease consultants, and intensive care. The survey assessed participant’s characteristics, factors potentially associated with resilience, and resilience using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (RISC-25), with higher scores indicative of greater resilience. Factors associated with the resilience score were assessed using a multivariable linear regression. Of 451 responding physicians involved in the care of COVID-19 patients, 442 were included (98%). Age was 36.1 ± 10.3 years and 51.8% were male; 63% worked in the emergency department (n = 282), 10.4% in anesthesiology (n = 46), 9.9% in infectious disease department (n = 44), 4.8% in intensive care unit (n = 21) or other specialties (n = 49). The median RISC-25 score was at 69 (IQR 62–75). Factors associated with higher RISC scores were anesthesia as a specialty, parenthood, no previous history of anxiety or depression and nor increased anxiety. To conclude, this study is the first to characterize levels of resilience among physicians involved in COVID-19 unit. Our data points to certain protective characteristics and some detrimental factors, such as anxiety or depression, that could be amenable to remediating or preventing strategies to promote resilience and support caregivers in a pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The upheavals induced by the pandemic linked to SARS-CoV-2 infections have historical proportions. Many hospitals worldwide have faced of a surge in patients with COVID-19, while others have been planning for it and reorganizing their entire operations to avoid being overwhelmed1,2. These new processes have involved increased bed capacity in ICUs and wards, separate patient streams, adoption of new technologies and communication systems, staff reassignment, and the reorganization of physical spaces3. Healthcare providers had to adapt to abrupt changes to their working conditions, and had to deal with new colleagues, unfamiliar working space, ever changing personal safety and treatment guidelines, while facing shortages of personal protective equipment, medications, and ventilators. They have cared daily for severely ill or dying patients on a daily basis, some of them their colleagues, while facing the risk of their own infection.

These dramatic events have highlighted the importance of resilience4. Resilience is the subject of growing interest in the fields of psychiatry, psychology, sociology, and economics. Resilience is an evolving concept, defined as the “resources as positive psychological, behavioral, and/or social adaptation in the face of stressors and adversities5”. Compared with nonmedical health workers, medical health workers have experienced a significantly higher prevalence of insomnia, anxiety, depression, somatization, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms6,7. In a Chinese multicentre survey of physicians, the prevalence of depression was 50.7%, anxiety 44.7%, insomnia 36.1%, and stress-related symptoms 73.4%8. However, after disasters, most people are resilient and do not develop long-lasting mental disorders . Although the negative effects of the current crisis on physicians’ well-being have been studied6,8,9, few studies have assessed “the force within everyone that drives them to seek self-actualization, altruism, wisdom, and harmony with a spiritual source of strengths,” namely resilience10. Wellness incorporates mental, physical, and spiritual health to protect against burnout. The primary aim of this study was therefore to assess physicians’ level of resilience and define factors that improve or decrease their resilience level.

Materials and methods

Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study between April 18 and May 10, 2020 that assessed physicians’ resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic in several French hospitals.

Participants and settings

Participants

Physicians of six initial centers were selected to participate in this study. Study participants were mainly emergency and intensive care physicians, anesthesiologists, and infectious disease specialists. We used a snowball sampling method11, i.e., the initial invitation to the physicians of the six participating centers stated that it was possible (but not obligatory) to disseminate the survey to colleagues in the same speciality. Only board-certified physicians could participate; therefore, excluding residents.

Participation was voluntary, and signed consent was not requested. Filling out the questionnaire was considered implicit proof of consent. No incentive was offered. Data were collected anonymously.

Assessment of caseload according to centers

The initial sample of six hospitals was selected according to their real caseload from each of three regions (low, moderate, high level of real caseload). To do this, we used the national real-time data published by the French Ministry of Health on COVID-1912. This caseload was mainly determined by region according to the proportion of usually open resuscitation beds that were then occupied by COVID-19 patients: high caseload above 60%, intermediate caseload between 40 and 60%, and low caseload between 0 and 40%. The centers of Angers and Nantes had a low, Cahors and Paris an intermediate, and Mulhouse and Colmar a high caseload.

Development and pretesting

Participants completed a 41-question survey specifically designed for this study. The questionnaire had three distinct sections: participant characteristics (5 questions), factors potentially associated with resilience (11 questions), and finally a resilience scale using the 25-item French version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 25)13. The scale explores seven domains of resilience: hardiness (i.e., commitment/challenge/control), coping, adaptability/flexibility, meaningfulness/purpose, optimism, regulation of emotion and cognition, and finally self-efficacy13. Each of the 25 items is rated on a 5-point scale (0–4), with a possible total score range from 0 to 100 points, with higher scores indicative of a greater resilience. In the US general population, from whom this score was derived, the median score was 82 points, with quartiles being 0–73, 74–82, 83–90, 91–10013. The scale has since been validated in the general population14,15,16, among patients with post-traumatic stress disorder17, and among healthcare workers18,19,20. Sensitive questions were asked, e.g., concerning recreational drug use, for which reason the survey was anonymous to guarantee the veracity of answers. In order to assess the factors associated with different levels of resilience and not overburden participants, anxiety requiring treatment, depression under treatment, stress and alcohol or tobacco consumption have been only assessed in a declarative way. Physicians were asked to assess subjectively their perceived caseload of patients with COVID-19 using a 5-level Likert scale (0: no caseload, 1: very low caseload, 2: low caseload, 3: normal caseload, 4: high caseload, 5: very high caseload). The questionnaire was pretested on a small sample of ten physicians before fielding the survey.

Survey administration

In each center, a local investigator sent a personal invitation email to the different specialists (mainly emergency physicians, intensivists, anesthesiologists, and clinical infectious disease consultants). The email contained a link to the online self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was posted on Google Forms®. The original investigators had the possibility of transferring this survey to their contacts in the same speciality. The survey was open, and to prevent multiple entries, we compared the participants’ characteristics and if similar, their questionnaire would have been removed. However, no duplicate questionnaire was found. The response rate could not be calculated, because of the snowball sampling methodology. A reminder was sent after 10 days to all local investigators.

The specific objective of this study, i.e., the measure of resilience, was not initially explained to participants, who were only informed that the e-survey addressed their mental health.

Analysis

Only completed questionnaires were analyzed. The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys was followed21.

Continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation, or median values with interquartile ranges, while categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test, and categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test. A bilateral p value < 0.05 indicated statistically significance. We performed a univariate analysis to select the predictor variables associated with higher level of resilience by using the Chi-square test. We then performed a multivariable linear regression with a backward stepwise elimination, initially including all variables associated with the CD-RISC-25 score with a p value < 0.2 in the univariate analysis. We verified the absence of collinearity between the explanatory variables. All data were analyzed using R (R Core Team, 2014, R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Angers University Hospital (A 2020–30) and declared on clinicaltrials.gov before inclusion of the first participant (NCT04349163).

Results

A total of 451 physicians caring for COVID-19 patients returned a fully completed questionnaire, of which 9 (2.3%) were subsequently excluded: 1 as the respondent was a pharmacologist not directly involved in patients’ care, 4 were residents, and 4 contained errors. Of 442 valid respondents, mean age was 36.1 ± 10.3 years and 213 (48.2%) were female (Table 1). Regarding the medical specialty, 282 were emergency physicians (63.3%), 46 anesthesiologists (10.4%), 44 infectious disease specialists (9.9%), and 21 intensive care specialists (4.8%). The remaining 49 physicians (11.1%) were from several other specialties (geriatric, pneumology, internal medicine, dermatology, cardiology, general medicine, etc.), dispatched to work in COVID-19 units. Almost all physicians were working full time (94.4%). According to the real caseload based on French national data, 65.2% of physicians were in a low (n = 288/442), 2.3% in a moderate (n = 10/442), and 32.5% in a high caseload area (n = 144/442). According to the physicians’ perceived caseload, 132 physicians (29.9%) considered to face a low caseload, 218 (49.3%) a normal caseload, and 91 (20.6%) a high caseload. The physician’s perception was not significantly discordant with national data. The median postgraduate training was 8 years (3–17). With regard to familial status, 71 (16.1%) were single and 371 (83.9%) lived with a partner; 267 (60.4%) had children. Almost all physicians were under curfew at home with their spouse or family (375/442, 84.8%). The others (15.2%) were alone or in another place, or with friends or relatives. Half of them were afraid of infecting their relatives (223/442, 50.5%) with the coronavirus. Few physicians reported increased tobacco use (20/442, 4.5%) or both tobacco and alcohol use (15/442, 3.4%), while significantly more increased their alcohol consumption (92/442, 20.8%).

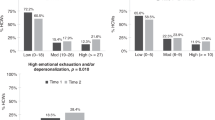

The median resilience score was at 69 (IQR 62–75), and several factors were associated with higher RISC scores (Tables 2, 3 and Fig. 1): medical specialties in anesthesia, a high caseload according to the national data (but not according to physician’s gestalt), and parenthood. On the other hand, physicians with a self-reported history of anxiety, stress, and/or depression and physicians who experienced increased anxiety during the pandemic period had lower resilience scores (p < 0.05). No other demographic variables could be associated with resilience scores. The different subscales of resilience were similar across caseload levels, but statistically different between emergency physicians and other specialties (p < 0.05), with higher scores for self-efficacy and hardiness, and lower scores for meaningfulness (Fig. 2).

Resilience was assessed using the CD-RISC 25 scale [0–100]. In the box plots, the boundary of the box closest to zero indicates the 25th percentile, a black line within the box marks the median, and the boundary of the box farthest from zero indicates the 75th percentile. *Median in the US general population in the original description of the CD-RISC25 = 83 (73–90). †Global comparison was performed using Kruskall–Wallis test (p = 0.02) and post-hoc test using Dunn test with a Hochberg multiple comparison procedure, p significant.

In the multivariate model, we included all variable significantly associated with higher level of resilience. The physician specialty (anesthesiology), parenthood, having no declared history of anxiety and/or depression, and no increased anxiety were associated with higher level of resilience during the COVID-19 crisis (Table 3).

Discussion

The Resi-CoV study is one of the first studies to assess resilience among physicians taking care of COVID patients. We found that median total RISC score was 69 points, but the range was wide, spanning from 38 to 97 points. Based on our multivariable linear regression model, to be an anesthesiologists, parents, without a history of anxiety, stress, or depression or without increased anxiety during the pandemic period were factors associated with a higher overall RISC score. The average scores of the seven components of the RISC score did not differ based on the caseload levels but differed between medical specialties. Emergency physicians had higher self-efficacy and meaningfulness/purpose subscores, but a lower meaningfulness subscore.

With a median CD-RISC-25 score of 69, the resilience score of surveyed French physicians was lower than that found in other studies conducted in the general US population13,22,23, corresponding to the lowest quartile13. A few studies have assessed the level of physicians’ resilience since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using the CD-RISC 25, in Wuhan, the resilience score was higher, at 73.48 ± 11.4924. Our results were also lower than those found among both inexperienced and experienced Chinese healthcare workers during the pandemic, with scores of 67.73 ± 14.85 and 75.36 ± 13.27, respectively25. Meynaar et al. found an increased prevalence of burnout among intensivists, which was inversely correlated to the resilience and work engagement scores26. Consistent results were found in Canada, and in Turkey: resilience was an important factor associate with reduced stress and distress during this COVID-19 crisis27,28.

However, as resilience is a process and not a stable trait throughout life, longitudinal data would be needed to measure the impact of the pandemic on population or individuals5,29.

One in four physicians in our sampled felt more anxious, one in five increased their consumption of alcohol, and one in twenty their tobacco consumption. Stress contributes to unhealthy behaviors30,31, in particular for those who are less resilient, and the long-term consequences of these behavioral changes will need to be reassessed. On the other hand, parenthood was significantly associated with higher levels of resilience5, pointing to the crucial contribution of a healthy work-family balance to the healthcare providers’ psychological well-being during this pandemic32. Indeed, being a parent could lead to overall well-being, a more positive emotional experience and meaning from one moment to the next33.

In this study, anesthesiologists had significant higher level of resilience. Stress is inherent to their daily practice, against which they may have developed psychological coping mechanisms34. However, they tend to be more prone to burnout than other physicians35,36. Emergency physicians were the most represented specialists in our study and showed a lower level of overall resilience. A recent study showed that the personality of residents in emergency medicine differed considerably from that of other physicians and, in response to stress, they may become risk averse37. On the other hand, residents in emergency medicine scored higher than other specialists in the self-efficacy and hardiness and lower in meaningfulness37. These results are consistent with our study finding conducted in certified emergency physicians.

No significant difference was found between the level of tension in centers. This can be explained by the fact that all the emergency departments needed a major reorganization in preparation for the surge of patients with COVID-19.

Using the CD-RISC, Mealer et al. showed that older age was significantly associated with high level of resilience among ICU nurses20. In a cross-sectional study in the UK National Health Service, a weak positive correlation between age and resilience was found among older employees displaying a higher level of resilience38. However, in our study, older respondents tended to score higher, although the difference failed to reach statistical significance.

Should low resilience among emergency physicians be the focus of an intervention program, beyond the current COVID-19 crisis? Resilience is a key component of maintaining personal health and quality of care in the workplace, despite adverse life events39,40,41. According to a meta-analysis based on cross-sectional studies, greater resilience is associated with less depressive symptomatology42. Many programs exist to improve resilience43,44, and some strategies may support health professionals’ resilience. The Ontario Medical Association—Physician Health Program suggests a series of ten practical steps to promote resilience during the COVID-19 crisis: from relying on basic notions of daily needs, in the management of friendly and family relationships up to rules of cohesion at work45,46. The French National Center for Resources and Resilience propose 11 steps for all people (not just caregivers): maintain the self-efficacy, tolerate uncertainty, increase our sense of security, remember the facts, let’s trust, be flexible when faced with the necessary adaptations, focus on activities that are good for well-being outside of your work, be kind to ourselves, look to the future with positive thoughts, stay in touch with friends and family, and increased our solidarity47. Team and individual debriefs are another method shown to decrease professional stress and improve concentration, morale, and commitment to work48. Debriefing meetings, as a team or individual during this difficult period, reinforce resilience to compassion fatigue49,50. During this period, department projects should be stopped to allow all the limited available time outside of care to be dedicated to healthcare workers’ relaxation, sleep, and family time39. In a recent letter, the benefit of online Balint group meetings on resilience, assessed by the CD-RISC 25 score, was suggested for a small group of healthcare providers caring for COVID-19 patients in Iran51. However, not all interventions have the same effectiveness52, and each program should be evaluated rigorously before implementation.

Resilience extends beyond individual healthcare providers, and applies to the intrinsic ability of hospitals and the healthcare system to cope during crises53. Resilience engineering, based on top management commitment, increased flexibility, learning lessons from both incidents, and normal operation and awareness of the system status, is an essential part of preparedness to face man-made or natural disaster54.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we included a large number of physicians involved in COVID patient care, relying on a snowball sampling methodology. The drawback if this approach is that we cannot know the participation rate, due to our lack of control over the email distribution list. Second, we found statistically significant differences between groups in the RISC score, but the minimally clinically significant difference on the RISC scale is unclear. Third, our sample comprises primarily emergency physicians, thus limiting the portability of our findings to other specialties. Fourth, respondents may differ from nonrespondents, and we cannot exclude a selection bias. Fifth, although the questionnaire was anonymous, some respondents may not have fully disclosed their behaviors or true level of resilience. Data concerning history of anxiety requiring treatment, of depression under treatment, of stress and alcohol or tobacco consumption were self-reported and are subject to recall or social desirability bias. Finally, although the CD-RISC score is well validated, resilience is a complex phenomenon and it is a process, not a trait5. Our survey provides a snapshot of the crisis and may not reflect a permanent trait in physicians caring for COVID-19 patients.

Conclusions

Resilience varied among French physicians, and lower scores were associated with increased anxiety with potentially harmful behaviors. Parenthood is associated with a higher level of resilience. The COVID-19 outbreak is an opportunity to reaffirm the importance of caring for the caregivers.

References

NHS England. Next steps on NHS response to COVID-19: letter from Sir Simon Stevens and Amanda Pritchard, 17 Mar 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/20200317-NHS-COVID-letter-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 06 Jun 2020.

WHO situation reports. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed 24 May 2020.

Lien, W.-C. et al. Fight COVID-19 beyond the borders: emergency department patient diversion in Taiwan. Ann. Emerg. Med. 75, 785–787 (2020).

Rosenbaum, L. Facing Covid-19 in Italy—ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1873–1875 (2020).

Fleming J., Ledogar R. J. Resilience, an evolving concept: a review of literature relevant to aboriginal research. 6, 7–23 (2010).

Zhang W. et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1159/000507639 (2020).

Escalera-Antezana J. P. et al. Healthcare workers’ and students’ knowledge regarding the transmission, epidemiology and symptoms of COVID-19 in 41 cities of Bolivia and Colombia. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 101702, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101702 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 7, e17–e18 (2020).

Rossi, R. et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2010185 (2020).

Richardson, G. E. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J. Clin. Psychol. 58, 307–321 (2002).

Naderifar, M., Goli, H. & Ghaljaie, F. Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 14, 1–4 (2017).

Santé Publique France. Géo données en santé publique (GEODES). https://geodes.santepubliquefrance.fr/#view=map2&c=indicator. Accessed 09 Jun 2020.

Connor, K. M. & Davidson, J. R. T. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 18, 76–82 (2003).

Houpy, J. C., Lee, W. W., Woodruff, J. N. & Pincavage, A. T. Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Med. Educ. Online 22, 1320187 (2017).

Codonhato, R. et al. Resilience, stress and injuries in the context of the Brazilian elite rhythmic gymnastics. PLoS ONE 13, e0210174 (2018).

Fu, C., Leoutsakos, J.-M. & Underwood, C. An examination of resilience cross-culturally in child and adolescent survivors of the 2008 China earthquake using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). J. Affect. Disord. 155, 149–153 (2014).

Blanc, J., Rahill, G. J., Laconi, S. & Mouchenik, Y. Religious beliefs, PTSD, depression and resilience in survivors of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. J. Affect. Disord. 190, 697–703 (2016).

Purvis, T. E., Neurocritical Care and Chaplaincy Study Group & Saylor, D. Burnout and Resilience Among Neurosciences Critical Care Unit Staff. Neurocrit. Care 31, 406–410 (2019).

Ong, H. L. et al. Resilience and burden in caregivers of older adults: moderating and mediating effects of perceived social support. BMC Psychiatry 18, 27 (2018).

Mealer, M. et al. The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: Results of a national survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 49, 292–299 (2012).

Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 6, e34 (2004).

Faria Anjos, J., Heitor dos Santos, M. J., Ribeiro, M. T. & Moreira, S. Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale: validation study in a Portuguese sample. BMJ Open 9, e026836 (2019).

Goins, R. T., Gregg, J. J. & Fiske, A. Psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale with older American Indians: the Native Elder Care Study. Res. Aging 35, 123–143 (2013).

Lin, J. et al. Factors associated with resilience among non-local medical workers sent to Wuhan, China during the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Psychiatry 20, 417 (2020).

Cai, W. et al. A cross-sectional study on mental health among health care workers during the outbreak of Corona Virus Disease 2019. Asian J. Psychiatry 51, 102111 (2020).

Meynaar, I. A., Ottens, T., Zegers, M., van Mol, M. M. C. & van der Horst, I. C. C. Burnout, resilience and work engagement among Dutch intensivists in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis: a nationwide survey. J. Crit. Care 62, 1–5 (2021).

Coulombe, S. et al. Risk and resilience factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a snapshot of the experiences of Canadian workers early on in the crisis. Front. Psychol. 11, 580702 (2020).

Arslan, H. N., Karabekiroglu, A., Terzi, O. & Dundar, C. The effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on physicians’ psychological resilience levels. Postgrad. Med. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2021.1874166 (2021).

Rutter, M. Environmentally mediated risks for psychopathology: research strategies and findings. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 44, 3–18 (2005).

Clay, J. M. & Parker, M. O. Alcohol use and misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: a potential public health crisis? Lancet Public Health 5, e259 (2020).

Ramchandani, V. A. et al. Stress vulnerability and alcohol use and consequences: from human laboratory studies to clinical outcomes. Alcohol 72, 75–88 (2018).

Blanchard, J. et al. For us, COVID-19 is personal. Acad. Emerg. Med. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14016 (2020).

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., English, T., Dunn, E. W. & Lyubomirsky, S. In defense of parenthood: children are associated with more joy than misery. Psychol. Sci. 24, 3–10 (2013).

van der Wal, R. A. B., Wallage, J. & Bucx, M. J. L. Occupational stress, burnout and personality inanesthesiologists. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 31, 351–356 (2018).

De Oliveira, G. S., Almeida, M. D., Ahmad, S., Fitzgerald, P. C. & McCarthy, R. J. Anesthesiology residency program director burnout. J. Clin. Anesthesia 23, 176–182 (2011).

Hyman, S. A. & Schildcrout, J. S. Risk of burnout in perioperative clinicians. Anesthesiology 114, 194–204 (2011).

Jordan, J. et al. Identifying the emergency medicine personality: a Multisite Exploratory Pilot Study. AEM Educ. Train. 2, 91–99 (2018).

Sull, A., Harland, N. & Moore, A. Resilience of health-care workers in the UK; a cross-sectional survey. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 10, 20 (2015).

Epstein, R. M. & Krasner, M. S. Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad. Med. 88, 301–303 (2013).

Zwack, J. & Schweitzer, J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Acad. Med. 88, 382–389 (2013).

Smith, G. D., Ng, F. & Ho Cheung Li, W. COVID‐19: emerging compassion, courage and resilience in the face of misinformation and adversity. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 1425–1428 (2020).

Wermelinger Ávila, M. P., Lucchetti, A. L. G. & Lucchetti, G. Association between depression and resilience in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis: depression and resilience in older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 32, 237–246 (2017).

Cleary, M., Kornhaber, R., Thapa, D. K., West, S. & Visentin, D. The effectiveness of interventions to improve resilience among health professionals: a systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 71, 247–263 (2018).

OMA Physician Health Program. Keeping yourself healthy: resilience and stress inoculation during COVID-19. http://php.oma.org/keeping-yourself-healthy-resilience-and-stress-inoculation-during-covid-19/. Accessed 05 Jun 2020.

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Disaster worker resiliency training. https://tools.niehs.nih.gov/wetp/public/hasl_get_blob.cfm?ID=10441. Accessed 10 Jun 2020.

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Disaster worker resiliency training. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/news/events/pastmtg/hazmat/assets/2018/wtp_spring_18_workshop_60_resilience_instructor_manual.pdf. Accessed 05 Jun 2020.

Molenda S. Centre National de Ressource et de Résilience. http://cn2r.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Renforcons-notre-resilience.pdf. Accessed 05 Jun 2020.

Tannenbaum, S. I. & Cerasoli, C. P. Do team and individual debriefs enhance performance? A meta-analysis. Hum. Factors 55, 231–245 (2013).

Schmidt, M. & Haglund, K. Debrief in emergency departments to improve compassion fatigue and promote resiliency. J. Trauma Nurs. 24, 317–322 (2017).

Adams, R. E., Boscarino, J. A. & Figley, C. R. Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: a validation study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 76, 103–108 (2006).

Kiani Dehkordi, M., Sakhi, S., Gholamzad, S., Azizpour, M. & Shahini, N. Online Balint groups in healthcare workers caring for the COVID-19 patients in Iran. Psychiatry Res. 290, 113034 (2020).

Joyce, S. et al. Road to resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open 8, e017858 (2018).

Shirali, G. H. A., Azadian, S. H. & Saki, A. A new framework for assessing hospital crisis management based on resilience engineering approach. WOR 54, 435–444 (2016).

Costella, M. F., Saurin, T. A. & de Macedo Guimarães, L. B. A method for assessing health and safety management systems from the resilience engineering perspective. Saf. Sci. 47, 1056–1067 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all investigators and physicians who participated to the Resi-CoV study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.D. and A.C. have designed the study. P.M., P.-M.R., D.S., and O.H. supervised the study. P.M., E.T., M.N., M.O., M.L., R.M., F.J. helped disseminate the questionnaire. J.R. reviewed the statistical analyses. D.D. and O.H. drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. D.D., A.C., and O.H. take responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Douillet, D., Caillaud, A., Riou, J. et al. Assessment of physicians’ resilience level during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Psychiatry 11, 283 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01395-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01395-7