Abstract

Direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) may prevail in microbial communities that show methanogenesis and anaerobic methane oxidation and can be an electron source to support anaerobic photosynthesis. Previous mutagenic studies on cocultures of defined Geobacter species indicate that both conductive pili and extracellular cytochromes are essential for DIET. However, the actual functional role of the pili in DIET is uncertain, as the pilus mutation strategy used in these studies affected the extracellular cytochrome profile. Here we repressed the function of pili by deleting the pilus polymerization motor PilB in both Geobacter species. The PilB mutation inhibited the pilus assembly but did not alter the pattern of extracellular cytochromes. We report that the two pilus-free Geobacter species can form aggregates and grow syntrophically with DIET. The results demonstrate that the Gmet_2896 cytochrome of Geobacter metallireducens plays a key role in DIET and that conductive pili are not necessary to facilitate DIET in cocultures of Geobacter species, and they suggest cytochromes by themselves can meditate DIET, deepening the understanding of DIET.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) was first demonstrated in the cocultures of Geobacter metallireducens with Geobacter sulfurreducens [1]. G. metallireducens cannot reduce fumarate, and G. sulfurreducens cannot oxidize ethanol. When these two species were inoculated in the medium with ethanol as electron donor and fumarate as electron acceptor, they formed a syntrophic partnership after aggregation with direct electrical connections [1]. Compared to mediated interspecies electron transfer (MIET), in which H2 or formate usually acts as an electron carrier, DIET has unique advantages under some circumstances and its biogeochemical impact may be significant, such as: (i) DIET is the predominant form of interspecies electron transfer in some anaerobic methanogenic digesters and may be involved in the production of atmospheric methane in terrestrial wetlands [2, 3]. (ii) DIET has been proposed to control methane release [4,5,6]. (iii) A recent finding indicates that DIET can be electron sources to support anaerobic photosynthesis [7].

The knowledge of DIET mainly originates from the study of cocultures between G. metallireducens and G. sulfurreducens, owing to the availability of genetic operation systems for both species. However, present knowledge of DIET is limited to the identification of key elements in this process, including the outer-surface Gmet_2896 cytochrome, flagella, and conductive pili of G. metallireducens [8] and the extracellular hexaheme cytochrome OmcS and conductive pili of G. sulfurreducens [1]. The proposed mechanism of DIET for these defined Geobacter species cocultures is that conductive pili from both Geobacter species facilitate the interspecific transfer of electrons with the help of cytochromes, which emphasizes the importance of the high conductivity of pili during DIET [9]. The importance of cytochromes in DIET is clear, such as the following: (i) the mutation of the above-mentioned cytochromes inhibits the formation of cocultures; (ii) the DIET community, such as anaerobic bioreactors for treatment of brewery wastes [10], methanogenic digestion of wastewater [3] and rice paddy soils [11], always contains Geobacter species at high abundance, which take a hall-mark feature of abundance with c-type cytochromes [12]; (iii) The metagenome of proposed DIET-based consortia of anaerobic methane-oxidizing archaeal group 1 (ANME-1) methanotrophic archaea coupled to sulfate reduction contains abundant genes encoding multi-heme cytochromes [13]; (iv) in the DIET consortia of ANME-2 with its sulfate-reducing partner, regions with dense heme-staining in the multicellular assemblages are visualized indicating a cytochrome-based electron transfer between species [5]; and (v) the outer membrane surface cytochrome OmcB of G. sulfurreducens is necessary for syntrophic anaerobic photosynthesis [7].

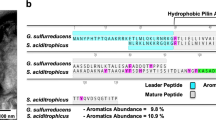

However, the electrically conductive function of pili in DIET seems ambiguous, as the nonconductive pili of Candidatus Desulfofervidus auxilii can also participate in DIET with ANME-1 [6, 14]. Moreover, the direct deletion of conductive pilin gene pilA of G. sulfurreducens affects the distribution and content of extracellular cytochromes [15, 16], especially OmcS (Fig. 1a, b). Unfortunately, all conclusions related to DIET based on conductive pili come from studies of pilin-deficient strains [1, 8, 17]. A new mutation strategy is warranted to unambiguously specify the function of conductive pili in DIET.

Extracellular cytochromes profile. a Heme-stained SDS-PAGE gel of extracellular c-type cytochromes prepared from G. sulfurreduencs strain PCA, pili mutant (PCA-∆pilA) and type IV pilus biogenesis ATPase deficient strain PCA-∆pilB. b Western blot analysis of extracellular proteins prepared from G. sulfurreducens strains PCA and PCA-∆pilA, and cell-free lysate from the OmcS mutant (PCA-∆OmcS) of G. sulfurreducens, and cytoplasm from PCA-∆pilA, using antibodies specific for OmcS. The deletion of pilA inhibited the excretion of OmcS in G. sulfurreducens. c Heme-stained SDS-PAGE gel of extracellular c-type cytochromes prepared from G. metallireducens strain GS15, pili mutant (GS-∆pilA), type IV pilus biogenesis ATPase deficient strain GS-∆pilB and the Gmet_2896 gene deletion strain of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB (strain GS-∆pilB∆Gmet_2896). The deletion of pilA inhibited the excretion of Gmet_2896 cytochrome in G. metallireducnes. The red and blue arrows indicate the OmcS and Gmet_2896 cytochrome bands, respectively, which are assigned based on molecular weight. 2 μg proteins were loaded on the gel

The pilA determines the expression of conductive pili, while the type IV pilus biogenesis ATPase PilB powers the polymerization of Geobacter pilin [18]. The PilB-deficient strain of G. sulfurreducens demonstrates no measurable differences in expression of extracellular cytochromes compared to the wild-type strain [16]. Here, we constructed PilB-deficient strains of both G. metallireducens and G. sulfurreducens. We found that the PilB-deficient Geobacter species possess integrated profiles of outer-surface cytochromes but cannot assemble conductive pili. However, these pili-free Geobacter species form cocultures readily with DIET, and the Gmet_2896 cytochrome plays a key role in this process. Our findings indicate that cytochromes by themselves can mediate DIET and suggest that DIET may widespread in natural environment.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and cultivation condition

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The wild-type strains, Geobacter sulfurreducens PCA (ATCC-51573) and Geobacter metallireducens GS15 (ATCC-53774), were obtained from the ATCC and used for the construction of related mutants. All Geobacter strains were cultured at 30 °C under strict anaerobic conditions (80%/20% N2/CO2) and were regularly grown in bicarbonate-buffered medium with 20 mM acetate as the electron donor and either 40 mM fumarate or 50 mM ferric citrate as the electron acceptor, as previously reported (Liu et al 2014b). Specially, H2 (138 KPa) was complemented in the medium for the cultivation of a citrate synthase-deficient strain of G. sulfurreducens, strain PCA-∆pilB∆gltA. When needed, agar (1.5%) and antibiotics were added to the medium for selection of all mutants on plates. For insoluble Fe(III) reduction analysis, 100 mM poorly crystalline Fe(III) oxide was used as the electron acceptor (Liu et al 2014b). The metabolism of Fe(III) was measured by using the FerroZine assay [19].

To coculture the mutants of G. sulfurreducens and G. metallireducens, 2% inoculum of each syntrophic partner was inoculated into a mineral-based medium with 20 mM ethanol as the electron donor and 40 mM fumarate as the electron acceptor, as previously described [20]. All cocultures were regularly transferred (2% inocula) under strict anaerobic conditions for at least six generations before monitoring growth. The growth of individual Geobacter strains and the cocultures containing the gene Gmet_2896 deletion strain of G. metallireducens (strain GS-∆pilB∆Gmet_2896) was analyzed during the initial inoculation because they cannot grow on ethanol. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was routinely used for cloning and was cultured at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani medium supplied with the appropriate antibiotics.

Generation of G. sulfurreducens and G. metallireducens mutants

All primers used for the construction of mutants and for the verification of mutant strains are listed in Supplementary Table 2. All G. metallireducens mutants were constructed following a previously published method [21]. To construct the G. metallireducens strain deficient in the type IV pilus biogenesis ATPase (PilB, GenBank locus Gmet_1393), GS-∆pilB, three fragments were prepared: first, the primer pairs gsBupf/gsBupr and gsBdnf/gsBdnr were used to amplify the sequences 500 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream, respectively, of Gmet_1393, using G. metallireducens genomic DNA as template and the primer pair spef/sper was used to amplify the spectinomycin resistance cassette flanked by loxP sites from plasmid pRG5. These three fragments were connected and inserted into the In-Fusion Cloning site of linear plasmid pUC19 (included in the kit) using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara Biomedical Technology, Beijing, China), generating the plasmid pUC-GspilB. The plasmid was linearized with NcoI (New England BioLabs (NEB), Ipswich, MA, USA) and then electroporated into electrocompetent G. metallireducens GS15. The deletion of pilB was confirmed by PCR (Supplementary Fig. S1). To construct the pilB and Gmet_2896 double-deletion strain of G. metallireducens, named GS-∆pilB∆Gmet_2896, the spectinomycin resistance cassette (sp-loxP) carried by GS-∆pilB was first excised from its chromosome by expressing the Cre recombinase from the plasmid pCM158 using a published procedure [21]. The excision of the antibiotic marker was confirmed by PCR with primer pairs verGmet1393F/verGmet1393R (Supplementary Fig. 1), generating the strain GS-∆pilB2. Two fragments, the sequences 500 bp upstream and downstream of gene Gmet_2896, were amplified from the G. metallireducens genome using the primer pairs Gs2896upf/Gs2896upr and Gs2896dnf/Gs2896dnr, respectively, and then, together with the fragment of sp-loxP, they were inserted into the pUC19 In-Fusion Cloning site using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit, generating the plasmid pUC-GS2896. After linearizing with NcoI (NEB), the plasmid was electroporated into the electrocompetent G. metallireducens strain GS-∆pilB2. The pilA (Gmet_1399) deletion strain of G. metallireducens was constructed following the same method, using the primer pairs GspilAupf/GspilAupr and GspilAdnf/GspilAdnr to amplify sequences 500 bp upstream and downstream of the gene Gmet_1399, and then connecting them with sp-loxP and the linearized plasmid pUC19, generating plasmid pUC-GspilA. The plasmid was linearized with NcoI (NEB) and then electroporated into electrocompetent G. metallireducens.

A previously published procedure was used to construct the G. sulfurreducens mutants [22]. To construct the G. sulfurreducens strain deficient in the type IV pilus biogenesis ATPase (PilB, GenBank locus GSU1491), PCA-∆pilB, three fragments were prepared: first, the primer pairs ppilBupf/ppilBupr and ppilBdnf/ppilBdnr were used to amplify the sequences 500 bp upstream and downstream, respectively, of GSU1491 with G. sulfurreducens genomic DNA as the template, and then, the primer pair gmf/gmr was used to amplify the gentamycin-resistance cassette flanked by loxP sites (Gm-loxP) from the plasmid pCM351. These fragments were connected with the linearized plasmid pUC19 using In-Fusion HD Enzyme, generating the plasmid pUC-PCApilB. The plasmid was linearized with NcoI (NEB) and then electroporated into electrocompetent G. sulfurreducens PCA. To construct the formate dehydrogenase (fdnG gene, GSU0777), uptake hydrogenase (hybL gene, GSU0785) and PilB triple-deficient strain, as well as the citrate synthase (gltA gene, GSU1106) and PilB double-deficient strain, of G. sulfurreducens, strains PCA-∆pilB∆fdnG∆hybL and PCA-∆pilB∆gltA, respectively, the gentamycin-resistance cassette (Gm-loxP) carried in the chromosome of PCA-∆pilB was excised by expressing the Cre recombinase from plasmid pCM158 following a published procedure [21]. The removal of Gm-loxP was confirmed by PCR with primer pairs verpilBf/verpilBr (Supplementary Fig. S1), generating strain PCA-∆pilB2. The primer pairs hybLupf/hybLupr and hybLdnf/hybLdnr were used to amplify the sequences 500 bp upstream and downstream of GSU0785, and the primer pairs gltAupf/gltAupr and gltAdnf/gltAdnr were used to amplify the corresponding sequences 500 bp upstream and downstream of GSU1106, each from the G. sulfurreducens genome. These fragments, together with Gm-loxP, were connected with the linearized plasmid pUC19 by In-Fusion HD Enzyme (Takara), generating the plasmids pUC-hybL and pUC-gltA, respectively. Plasmids were linearized by NcoI (NEB) and electroporated into the electrocompetent G. sulfurreducens strain PCA-∆pilB2, generating the strains PCA-∆ pilB∆hybL and PCA-∆ pilB∆gltA, respectively. The PilA-deficient strain of G. sulfurreducens, PCA-∆pilA, was constructed in a similar manner as a previous report [23] by in-frame deleting the pilA (GSU1496) and using the primer pairs pilAupf/pilAupr, pilAdnf/InpilAr and InpilAf/pilAdnr to amply the sequences last 500 bp of pilR, promoter of GSU1496 and downstream of GSU1496, respectively. To construct strain PCA-∆pilB∆fdnG∆hybL, the sequences 500 bp upstream and downstream of GSU0777 were amplified from PCA genome with the primer pairs fdnGupf/fdnGupr and fdnGdnf/fdnGdnr, respectively, and a kanamycin resistance cassette was amplified from the plasmid pCM158 with the primer pair kanf/kanr. These three fragments were connected with pUC19, generating plasmid pUC-fdnG, and then digested with NcoI (NEB) and transformed into the electrocompetent G. sulfurreducens strain PCA-∆pilB∆hybL. All mutants were verified by PCR (Supplementary Fig. S1) and Sanger sequencing.

SDS-PAGE gel analysis and Western blot

Extracellular proteins were collected from late-log-phase cells as previously described [24, 25] and quantified by using the bicinchoninic acid assay following the manufacturer’s instructions (Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Equal amounts of protein mixed with reducing SDS-PAGE loading buffer were loaded on 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA) and separated by SDS-PAGE. For heme-staining, non-reducing loading buffer was used. After electrophoresis, proteins were electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane with a semi-dry blotting system (Bio-Rad). The blotting membrane was sequentially incubated with ani-OmcS rabbit polyclonal antibodies and anti-rabbit secondary monoclonal antibody (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) following a previously described method [26]. The OmcS bands were detected by chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico kit, Thermo Scientific). Heme-staining was performed according to a previous study [27] by using N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylbenzidine to stain the hemes of c-type cytochromes.

Raising the anti-OmcS antibodies

The full-length of omcS gene (GSU2504) without the signal peptide sequences was amplified from G. sulfurreducens PCA genome with primer pairs OmcSndeI (5′-catatgTTCCACTCCGGCGGCGTT-3′) and OmcSxhoI (5′-ctcgagtGTCCTTGGCGTGGCACTTGT-3′). The PCR products were digested by NdeI (NEB) and XhoI (NEB), and were sub-cloned into pET-29a(+) plasmid between the NdeI and XhoI sites. The constructed vector carrying the OmcS-coding gene was sent out for protein overexpression and purification, and for antibody preparation (Genscript Biotech, Nanjing, China).

Analytical techniques

For monitoring the growth of cocultures, 500 μL of culture medium was sampled under strict anaerobic conditions and was filtered with a 0.2 μm sterilized filter. Samples were stored at 4 °C for a maximum of 1 week before testing. The organic acids were separated and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography as described in a previous study [20] using an Aminex NPX-87H column (Bio-Rad) with 8 mM H2SO4 as the eluent under a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1 and were detected at 210 nm by a UV detector (Thermo U-3000 HPLC, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ethanol was analyzed by gas chromatography performed on an Agilent 7890 A (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA) equipped with a headspace automatic sampler and an FID. Separation of ethanol was achieved with a HP-INNOWAX (Agilent) column (30 m length, 0.530 mm inner diameter, 1-μm film thickness) using N2 as the carrier gas and under the following conditions: 50 °C for 1 min, a ramp of 12 °C per minute to reach 200 °C, 1 min at 200 °C. The injector and front detector temperatures both were set at 200 °C.

Microscopy

For transmission electron microscopic imaging, a drop of culture was loaded on a 400-mesh carbon-coated copper grid and left at room temperature for 5 min before wiping with filter paper. Samples were negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate and imaged under a Tecnai 12 transmission electron microscope operating at 100 kV. The coculture aggregates were visualized by phase-contrast microscopy on a Leica DMi8 microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, United States).

The formation of syntrophic partners and the distribution of the two strains in the cocultures were verified by fluorescence in situ hybridization with strain-specific probes as previously described [1] and were visualized on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc.) using consecutive line scanning. Briefly, the cocultures were fixed by direct addition of paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde at final concentrations of 2% and 0.5%, respectively, followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. Aggregates were applied on a gelatin-coated slide, dried at 46 °C, and then dehydrated in 70% ethanol for 30 min at 4 °C. Slides were incubated at 46 °C for 2 h in hybridization buffer, which contained probe GEO1 (5′-[cy3]AGAATCCAAGGACTCCGT-3′), specific for G. metallireducens, and GEO2 (5′-[FAM]GAAGACAGGAGGCCCGAAA-3′, specific for G. sulfurreducens. After hybridization, slides were washed for 30 min in washing buffer at 48 °C, and then rinsed with Milli-Q water. Slides were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then were ready for confocal microscopy.

Results and discussion

Similar profiles of extracellular c-type cytochromes in PilB-deficient strains of Geobacter species

The conductive pili of G. sulfurreducens are mainly composed of geopilin, PilA, who shares certain characteristics with those of type II secretion systems [28]. Direct knockout of the pilA from G. sulfurreducens (strain PCA-∆pilA) altered its extracellular c-type cytochrome patterns (Fig. 1a), especially with regard to the c-type cytochrome OmcS, which disappeared from the extracellular matrix (Fig. 1a, b) and which is necessary during the direct interspecies electron transfer between G. metallireducens and G. sulfurreducens with ethanol as the only electron donor and fumarate as the only electron acceptor [1]. In contrast, deletion of the pilB from G. sulfurreducens (strain PCA-∆pilB) did not alter the extracellular c-type cytochrome patterns (Fig. 1a) but inhibited pilus assembly [16]. Similarly, deletion of pilA from G. metallireducens (strain GS-∆pilA) also affected its extracellular cytochrome profile (Fig. 1c), especially the Gmet_2896 cytochrome, which is necessary in DIET [8] and could not be detected in the extracellular matrix of GS-∆pilA. On the contrary, the deletion of pilB from G. metallireducens (strain GS-∆pilB) did not affect the extracellular c-type cytochrome profile (Fig. 1c).

Deletion of pilB from G. metallireducens inhibited pilus assembly and affected Fe(III) oxide reduction

The wild-type strain of G. metallireducens grew both pili and flagella (Fig. 2a) when Fe(III) citrate acted as an electron acceptor at 25 °C, a temperature inducing pilus synthesis in Geobacteraceae [21]. The motor ATPase PilB powers pilus assembly but not flagellar assembly. G. metallireducens strain GS-∆pilB expressed normal flagella but could not assemble pili (Fig. 2b). Pili of G. metallireducens are necessary for the reduction of insoluble outer cellular electron acceptors. Deletion of pilA from G. metallireducens (strain GS-∆pilA) inhibited the reduction of Fe(III) oxide but not reduction of soluble Fe(III) citrate [21]. G. metallireducens strain GS-∆pilB displayed certain Fe(III) reduction phenotype similar to that of strain GS-∆pilA and GS15, in which the reduction of soluble Fe(III) was unaffected (Fig. 2c), indicating that the deletion of pilB also did not affect electrons transfer to the outer cell surface of G. metallireducens, except that GS-∆pilB only showed diminished Fe(III) oxide reduction with a much longer lagging-phase and the incomplete reduction of total Fe (III)oxide (Fig. 2d), unlike G. metallireducens strain GS15.

Phenotypic characterization of G. metallireducens strains. Representative transmission electron micrographs of negatively stained (a) strain GS15 and (b) strain GS-∆pilB. The deletion of pilB inhibited the growth of pili. Representative of 16 and 23 images obtained, respectively. Both strains were cultured at 25 °C with ferric citrate as electron acceptor. Fe (II) production from the reduction of (c) Fe (III) citrate or (d) Fe (III) oxide by strain GS15, GS-∆pilB and GS-∆pilA. The pili did not contribute the electrons transfer to the outer cell surface but affected the extracellular electron transfer. The results shown were the means ± s.d. for triplicate cultures

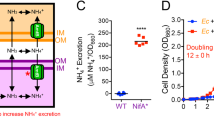

Direct interspecies electron transfer between GS-PilB and PCA-PilB in cocultures

G. metallireducens and G. sulfurreducens cocultures can form aggregates with DIET, a process that has been thought to require the participation of conductive pili from both species [1, 8]. When disable the expression of either pili of G. metallireducens or G. sulfurreducens, the cocultures cannot grow [1, 8]. Notably, in one study, it seems that the G. metallireducens pili are more important than G. sulfurreducens pili in DIET [29], as the magnetite can partially compensate the deficient of G. sulfurreducens pili in DIET cocultures but cannot compensate for the mutation of G. metallireducens pili. Either of the two pilus-assembly-deficient Geobacter species (G. metallireducens strain GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens strain PCA-∆pilB) could not grow individually in coculture medium with ethanol as electron donor and fumarate as electron acceptor (Fig. 3a, b). Surprisingly, they formed cocultures in which the oxidation of ethanol to acetate and the reduction of fumarate to succinate occurred as fast as in cocultures initiated with wild-type Geobacter species (Fig. 3c, d). Contact between syntrophic partners is the defining characteristic of DIET-based cocultures [2]. The cocultures of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB could also form obvious large flocks by associations of individual cells (Fig. 4a, b). After hybridization with strain-specific oligo probes, this cocultures demonstrated a composition of mixed strains with the domination of G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB (Fig. 4c).

Ethanol metabolism, acetate accumulation and succinate production from fumarate reduction of cocultures. a PilB-deficient strain PCA-∆pilB of G. sulfurreducens could not metabolize ethanol. b PilB-deficient strain GS-∆pilB of G. metallireducens could not reduce fumarate. c Cocultures of G. metallireducnes strain GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens strain PCA-∆pilB. d Cocultures of wild-type strains of G. metallireducens and G. sulfurreducens. e Cocultures of G. metallireducens strain GS-∆pilB and formate dehydrogenase, uptake hydrogenase, PilB triple-deficient strain PCA-∆pilB∆fdnG∆hybL of G. sulfurreducens. f Cocultures of G. metallireducnes strain GS-∆pilB and PilB, citrate synthase double deficient strain (PCA-∆pilB∆gltA) of G. sulfurreducens. The pili-deficient strains of both Geobacter species were able to form syntrophic growth with direct interspecies electron transfer. The results are the means ± s.d. for triplicate cocultures

Aggregates formed in the cocultures of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB. a Appearance of the aggregates. b Phase-contrast micrograph of aggregates. c Scanning laser confocal microscope image of aggregates after fluorescence in situ hybridization of strain-specific probes. The G. metallireducens strain GS-∆pilB was labeled with a green probe, and the G. sulfurreducens strain PCA-∆pilB was labeled with a red probe. Representative aggregates of 23 similar aggregates recorded

To eliminate the possibility of H2 and/or formate facilitating interspecies electron transfer, cocultures were initiated with the G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB and a G. sulfurreducens strain, PCA-∆pilB∆hybL∆fdnG, which cannot assemble pili and metabolize H2 and formate owing to the triple deletion of the pilB gene, the large subunit of the uptake hydrogenase (gene hybL) [30] and the catalytic subunit of formate dehydrogenase (gene fdnG) [20]. As expected, the cocultures also grew with the metabolism of ethanol and the reduction of fumarate to succinate (Fig. 3e). Here acetate also accumulated.

G. metallireducens catabolizes ethanol to acetate, and G. sulfurreducens oxidizes the acetate to reduce fumarate. To evaluate the possibility of metabolic coupling between these syntrophic species, cocultures were initiated with the G. metallireducens strain GS-∆pilB and such a G. sulfurreducens strain that cannot assemble pili and catabolize acetate (deletion of the citrate synthase gene, gltA) [31], strain PCA-∆pilB∆gltA. As previously reported for cocultures of G. metallireducens and citrate synthase-deficient G. sulfurreducens [32], the cocultures of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB with G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB∆gltA metabolized ethanol as fast as the cocultures of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB with G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB (Fig. 3f). Acetate accumulated continuously in the cocultures, with more ethanol oxidized and acetate generated from reduction of the same amount of fumarate than in the cocultures of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB with G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB (Fig. 3f). The much higher acetate accumulation in the cocultures of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB∆gltA than in the cocultures between G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB implies that acetate produced by ethanol catabolism of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB can also be metabolized by G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB to provide electrons for the reduction of fumarate, which is the same case as in the wild-type cocultures of G. metallireducens with G. sulfurreducens [32].

The electrons derived from DIET cocultures can support the cell growth [32]. The stoichiometry of metabolism in Geobacter species cocultures was calculated based on the following formulas:

In theory, the electrons generated from the total oxidation of 1 mM ethanol and 1 mM acetate can reduce 6 mM fumarate producing 6 mM succinate (Reaction 1) and reduce 4 mM fumarate producing 4 mM succinate (Reaction 3, 4), respectively. When G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB was cocultured with G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB, 9.34 mM ethanol was catabolized associated with the formation of 39.34 mM succinate and the accumulation of 1.95 mM acetate, accounting for electron recoveries of 81.6%. The ratio is consistent with previously reported Geobacter cocultures, in which partial metabolism of ethanol has been used for the biomass production [33].

The partial catabolism of 1 mM ethanol can generate 1 mM acetate and release 4 mM electrons (Reaction 2) reducing 2 mM fumarate to generate 2 mM succinate. However, in cocultures between G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB∆gltA, the metabolism of 14.76 mM ethanol was associated with the generation of 39.14 mM succinate and the accumulation of 10.74 mM acetate. Considering acetate also can be the electron donor for G. metallireducens to grow in DIET cocultures [34] and G. sulfurreducens does not use H2 and formate as electron donor in DIET cocultures (Fig. 3e) [32] and in addition, the transcription of both formate dehydrogenase and uptake hydrogenase of G. sulfurreducens in cocultures of G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB∆gltA were comparable with those in cocultures of G. metallireducens GS15 and synthase-deficient strain of G. sulfurreducens (data not shown), the extra electrons used for the reduction of fumarate must come from the oxidation of acetate by G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB. So the electron recoveries from the metabolism of ethanol were 85.83%, which is also consistent with previous reports of DIET cocultures [32, 35].

Gmet_2896 cytochrome is necessary for DIET between pili-free Geobacter species

The Gmet_2896 tetraheme cytochrome is located on the outer surface of G. metallireducens and is essential for insoluble Fe (III) oxide reduction but not for the reduction of soluble Fe (III) citrate [25], indicating a key role in extracellular electron transfer of G. metallireducens. A previous study showed that the Gmet_2896 mutant of G. metallireducens cannot form cocultures with G. sulfurreducens [8], which indicates that Gmet_2896 cytochrome also plays a critical role in the DIET. The same mutation was constructed in G. metallireducens strain GS-∆pilB, generating strain GS-∆pilB∆Gmet_2896. Attempts to establish cocultures between G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB∆Gmet_2896 and G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB were unsuccessful even after extended growth (Fig. 5a) when both species were grown in a medium containing ethanol as the electron donor and fumarate as the electron acceptor. Notably, the deletion of Gmet_2896 gene did not affected the distribution of extracellular cytochromes (Fig. 1c).

Cocultures. a Ethanol metabolism of cocultures between the G. metallireducens double-mutant strain lacking the extracellular Gmet_2896 c-type cytochrome, and PilB (strain GS- ∆pilB∆Gmet_2896) and strain PCA-∆pilB. These two strains cannot form cocultures. The results are shown as the means ± standard deviations for triplicate cultures. b Model of long-range DIET mediated by cytochromes in cocultures between G. metallireducens GS-∆pilB and G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB. The DIET was mediated via electron hopping between extracellular cytochromes

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that although conductive pili are necessary during extracellular electron transfer between Geobacter species to reduce extracellular insoluble electron acceptors, such as anodes [21, 36], they do not play a key role in the DIET between G. metallireducens and G. sulfurreducens. In constrast, the extracellular Gmet_2896 cytochrome of G. metallireducens is necessary for the DIET. The pilA determines the expression of PilA protein and affects the distribution of outer-surface cytochromes, while PilB just motors the assembly of type IV pili and deletion of pilB does not alter the distribution of extracellular cytochromes. The deletion of PilB should be a better choice to characterize the pilus related phenotype of Geobacter species.

Deletion of the pilA impaired the distribution of the extracellular cytochrome OmcZ [16] and OmcS (Fig. 1a, b), which plays a key role in DIET [1]. Considering that the extracellular OmcS is attached on pili [37] but not always associated [38], and that the strain G. sulfurreducens PCA-∆pilB has pattern of extracellular cytochromes similar to that of G. sulfurreducens strain PCA, it can be speculated that the pilin of G. sulfurreducens can aid the excretion of OmcS. G. sulfurreducens pili are conductive [39, 40] and even G. metallireducens pili show much higher conductivity [41]. Conductive pili have been thought to be essential during DIET between different syntrophic species [1, 2]. However, in the syntrophic consortia of G. metallireducens with G. sulfurreducens, the pili of G. sulfurreducens is moderately expressed comparing with the cocultures with MIET [8]. Moreover, the nonconductive flagella [8] and nonconductive pili [6, 14] also play key roles in DIET. Integrating those reports with our study, it can be inferred that the growth of conductive pili should not be suggested to be a criterion for selecting cocultures with DIET and investigations to identify the nonconductive function of filament structure in cocultures with DIET are warranted.

Our study highlights the importance of extracellular cytochromes in DIET. Even the normal expression of conductive pili cannot compensate for the deficient expression of either OmcS or Gmet_2896 cytochrome in DIET [1, 8]. The cytochromes involved in DIET can be ubiquitous, as all published DIET cocultures contain abundant cytochromes [1, 8]. Notably, cytochrome-mediated DIET has been evidenced only between species with outer cell surfaces tightly connected [5, 7], and this does not yet exclude the function of conductive pili during this process. Previous studies indicat that in electroactive biofilms, the electrons can hop among cytochromes to transfer a long distance [42,43,44]. Considering that the two Geobacter species were clustered individually in long-range DIET cocultures (Fig. 4c) [1] and cells were not tight contact in Geobacter cocultures (Figure S2) [1], it can be speculated that cytochromes alone can mediate DIET not only between intimately contacted species but between spatially separated species (Fig. 5b).

Conductive pili are mainly restricted to the order of Desulfuromonadales [45], but cytochromes are widely distributed in microbial world. The discovery of conductive pili-free DIET solely mediated by the extracellular cytochromes suggests that DIET syntrophic consortia may be ubiquitous in natural environments. The abundance of cytochromes in the extracellular matrix can act as a criterion to identify syntrophic consortia with DIET. Cytochromes facilitate electrons to transfer along electron transport chains, to cross the cell membrane and to reduce extracellular electron acceptors (Fe (III) oxide, humic substances or in our case syntrophic partners et al.). Our findings reveal a general bio-electron transport way, involved by cytochromes, in the biological world that electrons hop between the redox active cofactors.

References

Summers ZM, Fogarty HE, Leang C, Franks AE, Malvankar NS, Lovley DR. Direct exchange of electrons within aggregates of an evolved syntrophic coculture of anaerobic bacteria. Science. 2010;330:1413–5.

Lovley DR. Syntrophy goes electric: Direct interspecies electron transfer. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2017;71:643–64.

Morita M,Malvankar NS,Franks AE,Summers ZM,Giloteaux L,Rotaru AE, et al. Potential for direct interspecies electron transfer in methanogenic wastewater digester aggregates. mBio. 2011;2:e00159-11

Krukenberg V, Harding K, Richter M, Glöckner FO, Gruber-Vodicka HR, Adam B, et al. Candidatus Desulfofervidus auxilii, a hydrogenotrophic sulfate-reducing bacterium involved in the thermophilic anaerobic oxidation of methane. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:3073–91.

McGlynn SE, Chadwick GL, Kempes CP, Orphan VJ. Single cell activity reveals direct electron transfer in methanotrophic consortia. Nature. 2015;526:531–5.

Wegener G, Krukenberg V, Riedel D, Tegetmeyer HE, Boetius A. Intercellular wiring enables electron transfer between methanotrophic archaea and bacteria. Nature. 2015;526:587–90.

Ha PT, Lindemann SR, Shi L, Dohnalkova AC, Fredrickson JK, Madigan MT, et al. Syntrophic anaerobic photosynthesis via direct interspecies electron transfer. Nat Commun. 2017;8:13924.

Shrestha PM, Rotaru A-E, Summers ZM, Shrestha M, Liu F, Lovley DR. Transcriptomic and genetic analysis of direct interspecies electron transfer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013b;79:2397–404.

Shrestha PM, Rotaru A-E. Plugging in or going wireless: strategies for interspecies electron transfer. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:237.

Shrestha PM, Malvankar NS, Werner JJ, Franks AE, Elena-Rotaru A, Shrestha M, et al. Correlation between microbial community and granule conductivity in anaerobic bioreactors for brewery wastewater treatment. Bioresour Technol. 2014;174:306–10.

Holmes DE,Shrestha PM,Walker DJF,Dang Y,Nevin KP,Woodard TL, et al. Metatranscriptomic evidence for direct interspecies electron transfer between Geobacter and Methanothrix species in methanogenic rice paddy soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e00223-17

Butler JE, Young ND, Lovley DR. Evolution of electron transfer out of the cell: comparative genomics of six Geobacter genomes. BMC Genom. 2010;11:40.

Meyerdierks A, Kube M, Lombardot T, Knittel K, Bauer M, Glӧckner FO, et al. Insights into the genomes of archaea mediating the anaerobic oxidation of methane. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1937–51.

Walker DJF, Adhikari RY, Holmes DE, Ward JE, Woodard TL, Nevin KP, et al. Electrically conductive pili from pilin genes of phylogenetically diverse microorganisms. ISME J. 2018;12:48–58.

Cologgi DL, Lampa-Pastirk S, Speers AM, Kelly SD, Reguera G. Extracellular reduction of uranium via Geobacter conductive pili as a protective cellular mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15248–52.

Steidl RJ, Lampa-Pastirk S, Reguera G. Mechanistic stratification in electroactive biofilms of Geobacter sulfurreducens mediated by pilus nanowires. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12217.

Rotaru A-E, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Shrestha M, Shrestha D, Embree M, et al. A new model for electron flow during anaerobic digestion: Direct interspecies electron transfer to Methanosaeta for the reduction of carbon dioxide to methane. Energy Environ Sci. 2014;7:408–15.

McCallum M, Tammam S, Khan A, Burrows LL, Howell PL. The molecular mechanism of the type IVa pilus motors. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15091.

Lovley DR, Phillips EJP. Novel mode of microbial energy metabolism: Organic carbon oxidation coupled to dissimilatory reduction of iron or manganese. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1472–80.

Rotaru A-E, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Ueki T, Nevin K, Summers ZM, et al. Interspecies electron transfer via hydrogen and formate rather than direct electrical connections in cocultures of Pelobacter carbinolicus and Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7645–51.

Tremblay P-L, Aklujkar M, Leang C, Nevin KP, Lovley D. A genetic system for Geobacter metallireducens: role of the flagellin and pilin in the reduction of Fe(III) oxide. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2012;4:82–8.

Coppi MV, Leang C, Sandler SJ, Lovley DR. Development of a genetic system for Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:3180–7.

Richter LV, Sandler SJ, Weis RM. Two isoforms of Geobacter sulfurreducens PilA have distinct roles in pilus biogenesis, cytochrome localization, extracellular electron transfer, and biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:2551–63.

Mehta T, Coppi MV, Childers SE, Lovley DR. Outer membrane c-type cytochromes required for Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxide reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8634–41.

Smith JA, Lovley DR, Tremblay P-L. Outer cell surface components essential for Fe(III) oxide reduction by Geobacter metallireducens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;79:901–7.

Liu X, Tremblay P-L, Malvankar NS, Nevin KP, Lovley DR, Vargas M. A Geobacter sulfurreducens strain expressing Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pili localizes OmcS on pili but is deficient in Fe(III) oxide reduction and current production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014a;80:1219–24.

Thomas PE, Ryan D, Levin W. An improved staining procedure for the detection of the peroxidase activity of cytochrome P-450 on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1976;75:168–76.

Reguera G, McCarthy KD, Mehta T, Nicoll JS, Tuominen MT, Lovley DR. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature. 2005;435:1098–101.

Liu F, Rotaru A-E, Shrestha PM, Malvankar NS, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. Magnetite compensates for the lack of a pilin-associated c-type cytochrome in extracellular electron exchange. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:648–55.

Coppi MV, O’Neil RA, Lovley DR. Identification of an uptake hydrogenase required for hydrogen-dependent reduction of Fe(III) and other electron acceptors by Geobacter sulfurreducens. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3022–8.

Ueki T, Lovley DR. Genome-wide gene regulation of biosynthesis and energy generation by a novel transcriptional repressor in Geobacter species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:810–21.

Shrestha PM, Rotaru A-E, Aklujkar M, Liu F, Shrestha M, Summers ZM, et al. Syntrophic growth with direct interspecies electron transfer as the primary mechanism for energy exchange. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013a;5:904–10.

Liu F, Rotaru A-E, Shrestha PM, Malvankar NS, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. Promoting direct interspecies electron transfer with activated carbon. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5:8982–9.

Wang L-Y, Nevin KP, Woodard TL, Mu B-Z, Lovley DR. Expanding the diet for DIET: Electron donors supporting direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) in defined co-cultures. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:236.

Chen S, Rotaru A-E, Shrestha PM, Malvankar NS, Liu F, Fan W, et al. Promoting interspecies electron transfer with biochar. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5019.

Reguera G, Nevin KP, Nicoll JS, Covalla SF, Woodard TL, Lovley DR. Biofilm and nanowire production leads to increased current in Geobacter sulfurreducens fuel cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7345–8.

Leang C, Qian X, Mester T, Lovley DR. Alignment of the c-type cytochrome OmcS along pili of Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:4080–4.

Veazey JP, Reguera G, Tessmer SH. Electronic properties of conductive pili of the metal-reducing bacterium Geobacter sulfurreducens probed by scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2011;84:060901.

Malvankar NS, Vargas M, Nevin KP, Franks AE, Leang C, Kim B-C, et al. Tunable metallic-like conductivity in microbial nanowire networks. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:573.

Feliciano GT, Steidl RJ, Reguera G. Structural and functional insights into the conductive pili of Geobacter sulfurreducens revealed in molecular dynamics simulations. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17:22217–26.

Tan Y, Adhikari RY, Malvankar NS, Ward JE, Woodard TL, Nevin KP, et al. Expressing the Geobacter metallireducens PilA in Geobacter sulfurreducens yields pili with exceptional conductivity. mBio. 2017;8:e02203–16.

Snider RM, Strycharz-Glaven SM, Tsoi SD, Erickson JS, Tender LM. Long-range electron transport in Geobacter sulfurreducens biofilms is redox gradient-driven. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15467–72.

Yates MD, Golden JP, Roy J, Strycharz-Glaven SM, Tsoi S, Erickson JS, et al. Thermally activated long range electron transport in living biofilms. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17:32564–70.

Yates MD, Strycharz-Glaven SM, Golden JP, Roy J, Tsoi S, Erickson JS, et al. Measuring conductivity of living Geobacter sulfurreducens biofilms. Nat. Nano. 2016;11:910–3.

Holmes DE, Dang Y, Walker DJF, Lovley DR. The electrically conductive pili of Geobacter species are a recently evolved feature for extracellular electron transfer. Microb Genom. 2016;2:e000072.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Prof. Shiming Wang of Nanjing University of Science and Technology for kindly providing plasmid pCM158, and we thank Prof. Derek Lovley of University of Massachusetts, Amherst for providing the OmcS mutant of G. sulfurreduces. We thank Prof. Xiangzhen Li for constructive criticism of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Qianzhuo Mao and the Center for Molecular Cell and Systems Biology of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, respectively, for electron microscopy and laser scanning confocal microscopy. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grants no. 31600089, no. 41671264 and no. 91751109.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Zhuo, S., Rensing, C. et al. Syntrophic growth with direct interspecies electron transfer between pili-free Geobacter species. ISME J 12, 2142–2151 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0193-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0193-y

This article is cited by

-

Biophotoelectrochemical process co-driven by dead microalgae and live bacteria

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Light-independent anaerobic microbial oxidation of manganese driven by an electrosyntrophic coculture

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Cryo-EM structure of an extracellular Geobacter OmcE cytochrome filament reveals tetrahaem packing

Nature Microbiology (2022)

-

Light-driven carbon dioxide reduction to methane by Methanosarcina barkeri in an electric syntrophic coculture

The ISME Journal (2022)

-

Structure of Geobacter pili reveals secretory rather than nanowire behaviour

Nature (2021)