Abstract

Background

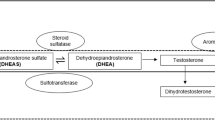

Evidence suggests that prostate cancer (PC) patients undergoing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) are at risk for cognitive decline (CD), but the underlying mechanisms are less clear. In the present study, changes in cognitive performance and structural brain connectomes in PC patients undergoing ADT were assessed, and associations of cognitive changes with endocrine status and risk genotypes were explored.

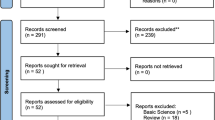

Methods

Thirty-seven PC patients underwent cognitive assessment, structural MRI, and provided blood samples prior to ADT and after 6 months of treatment. Twenty-seven age- and education-matched healthy controls (HCs) underwent the same assessments. CD was determined using a standardized regression-based approach and defined as z-scores ≤ −1.64. Changes in brain connectomes were evaluated using graph theory. Associations of CD with testosterone levels and genotypes (APOE, COMT, BDNF) were explored.

Results

Compared with HCs, PC patients demonstrated reduced testosterone levels (p < 0.01) and higher rates of decline for 13 out of 15 cognitive outcomes, with three outcomes related to two cognitive domains, i.e., verbal memory and visuospatial learning and memory, reaching statistical significance (p ≤ 0.01–0.04). Testosterone level changes did not predict CD. COMT Met homozygote PC patients evidenced larger reductions in visuospatial memory compared with Val carriers (p = 0.02). No between-group differences were observed in brain connectomes across time, and no effects were found of APOE and BDNF.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that PC patients undergoing ADT may evidence CD, and that COMT Met homozygotes may be at increased risk of CD. The results did not reveal changes in brain connectomes or testosterone levels as underlying mechanisms. More research evaluating the role of ADT-related disruption of the dynamics of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis is needed.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 4 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $64.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Data visualization tools for exploring the global cancer burden in 2018. 2020. http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home.

Liede A, Hallett DC, Hope K, Graham A, Arellano J, Shahinian VB. International survey of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for non-metastatic prostate cancer in 19 countries. ESMO Open. 2016;18:e000040.

Treanor CJ, Li J, Donnelly M. Cognitive impairment among prostate cancer patients: An overview of reviews. Eur J Cancer Care. 2016;26. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12642.

McGinty HL, Phillips KM, Jim HS, Cessna JM, Asvat Y, Cases MG, et al. Cognitive functioning in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2271–80.

Sun M, Cole AP, Hanna N, Mucci LA, Berry DL, Basaria S, et al. Cognitive impairment in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2018;199:1417–25.

McHugh DJ, Root JC, Nelson CJ, Morris MJ. Androgen-deprivation therapy, dementia, and cognitive dysfunction in men with prostate cancer: How much smoke and how much fire? Cancer. 2018;124:1326–34.

Kluger J, Roy A, Chao HH. Androgen deprivation therapy and cognitive function in prostate cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22:24.

Cherrier MM, Higano CS. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy on mood, cognition, and risk for AD. Urol Oncol. 2020;38:53–61.

Deprez S, Kesler SR, Saykin AJ, Silverman DHS, de Ruiter MB, McDonald BC. International cognition and cancer task force recommendations for neuroimaging methods in the study of cognitive impairment in Non-CNS cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:223–31.

Buskbjerg C, Zachariae R, Buus S, Gravholt CH, Haldbo-Classen L, Hosseini SMH, et al. Cognitive performance in newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients scheduled for androgen deprivation therapy - exploring the role of brain networks, endocrine status, and risk genotypes. Cancer. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33387.

Rubinov M, Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. NeuroImage. 2010;52:1059–69.

Cherrier MM, Borghesani PR, Shelton AL, Higano CS. Changes in neuronal activation patterns in response to androgen deprivation therapy: a pilot study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10.

Chao HH, Uchio E, Zhang S, Hu S, Bednarski SR, Luo X, et al. Effects of androgen deprivation on brain function in prostate cancer patients - a prospective observational cohort analysis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:371.

Cherrier MM, Cross DJ, Higano CS, Minoshima S. Changes in cerebral metabolic activity in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy for non-metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21:394–402.

Chao HH, Hu S, Ide JS, Uchio E, Zhang S, Rose M, et al. Effects of androgen deprivation on cerebral morphometry in prostate cancer patients-an exploratory study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72032.

Hammond J, Le Q, Goodyer C, Gelfand M, Trifiro M, LeBlanc A. Testosterone-mediated neuroprotection through the androgen receptor in human primary neurons. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1319–26.

Ahlbom E, Prins GS, Ceccatelli S. Testosterone protects cerebellar granule cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death through a receptor mediated mechanism. Brain Res. 2001;892:255–62.

Salminen EK, Portin RI, Koskinen A, Helenius H, Nurmi M. Associations between serum testosterone fall and cognitive function in prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7575–82.

Clay CA, Perera S, Wagner JM, Miller ME, Nelson JB, Greenspan SL. Physical function in men with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1325–33.

Salminen EK, Portin RI, Koskinen AI, Helenius HYM, Nurmi MJ. Estradiol and cognition during androgen deprivation in men with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1381–7.

Matousek RH, Sherwin BB. A randomized controlled trial of add-back estrogen or placebo on cognition in men with prostate cancer receiving an antiandrogen and a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:215–25.

Taylor AE, Keevil B, Huhtaniemi IT. Mass spectrometry and immunoassay: how to measure steroid hormones today and tomorrow. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173:D1–12.

Handelsman DJ, Wartofsky L. Requirement for mass spectrometry sex steroid assays in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3971–3.

Kovacs D, Vassos E, Liu X, Sun X, Hu J, Breen G, et al. The androgen receptor gene polyglycine repeat polymorphism is associated with memory performance in healthy Chinese individuals. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:947–52.

Buskbjerg C, Amidi A, Demontis D, Nissen ER, Zachariae R. Genetic risk factors for cancer-related cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:537–47.

Ahles TA, Root JC. Cognitive Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatments. Ann Rev Clinl Psychol. 2018;14:425–51.

Brierley J, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C, O’Sullivan B. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 8 ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2017.

Wefel JS, Vardy J, Ahles T, Schagen SB. International Cognition and Cancer Task Force recommendations to harmonise studies of cognitive function in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:703–8.

Benedict R, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised: normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;12:43–55.

Benton A, Hamsher KDS. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. iowa City; AJA Associates: 1989.

Ruff RM, Light RH, Parker SB, Levin HS. Benton Controlled Oral Word Association Test: reliability and updated norms. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1996;11:329–38.

Harrison JE, Buxton P, Husain M, Wise R. Short test of semantic and phonological fluency: normal performance, validity and test-retest reliability. Br J Clin Psychol. 2000;39:181–91.

Reitan R. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–6.

Wagner S, Helmreich I, Dahmen N, Lieb K, Tadic A. Reliability of three alternate forms of the trail making tests a and B. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;26:314–21.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 4th ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2008.

Wechsler D. WMS-III administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997.

Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Bigler ED, Tranel D. Neuropsychological Assessment. 5ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Climie EA, Rostad K. Test Review: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2011;29:581–6.

Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: Computer version. 2nd ed. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1993.

Greve KW, Love JM, Sherwin E, Mathias CW, Houston RJ, Brennan A. Temporal STability of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in A Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury Sample. Assessment. 2002;9:271–7.

Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3666–72.

Buskbjerg R, Zachariae B, Agerbaek M, Gravholt CH, Hosseini SMH, Amidi A. Cognitive performance in newly orchiectomized testicular cancer patients—exploring the role of brain networks, endocrine status, and risk genotypes. Brain Imagin Behav.

IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY; IBM Corp. https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/how-cite-ibm-spss-statistics-or-earlier-versions-spss.

Ouimet LA, Stewart A, Collins B, Schindler D, Bielajew C. Measuring neuropsychological change following breast cancer treatment: An analysis of statistical models. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2009;31:73–89.

Leemans A, Jeurissen B, Sijbers J, Jones D. ExploreDTI: a graphical toolbox for processing, analyzing, and visualizing diffusion MR data. In: Proceedings of the 17th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Honolulu, USA, 2009:3537.

Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated Anatomical Labeling of Activations in SPM Using a Macroscopic Anatomical Parcellation of the MNI MRI Single-Subject Brain. NeuroImage. 2002;15:273–89.

Hosseini H GAT: a graph-theoretical analysis toolbox for analyzing between-group differences in large-scale structural and functional brain networks. PLoS ONE. 7:e40709. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040709.

Latora V, Marchiori M. Efficient behavior of small-world networks. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;87:198701.

Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:186–98.

Hosseini SMH, Kesler SR. Influence of choice of null network on small-world parameters of structural correlation networks. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67354.

Pijnenburg M, Hosseini SM, Brumagne S, Janssens L, Goossens N, Caeyenberghs K. Structural brain connectivity and the sit-to-stand-to-sit performance in individuals with nonspecific low back pain: a diffusion magnetic resonance imaging-based network analysis. Brain Connect. 2016;6:795–803.

Kesler SR, Watson CL, Blayney DW. Brain network alterations and vulnerability to simulated neurodegeneration in breast cancer. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:2429–42.

Kesler SR, Gugel M, Huston-Warren E, Watson C. Atypical structural connectome organization and cognitive impairment in young survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Brain Connect. 2016;6:273–82.

Amidi A, Hosseini SMH, Leemans A, Kesler SR, Agerbaek M, Wu L, et al. Changes iN Brain Structural Networks and Cognitive Functions in Testicular Cancer Patients Receiving Cisplatin-based Chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Instit. 2017;109. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx085.

Linn MC, Petersen AC. Emergence and characterization of sex differences in spatial ability: a meta-analysis. Child Dev. 1985;56:1479–98.

Holland J, Bandelow S, Hogervorst E. Testosterone levels and cognition in elderly men: a review. Maturitas. 2011;69:322–37.

McEwen BS. Neural gonadal steroid actions. Science. 1981;211:1303–11.

Barkus C, Korn C, Stumpenhorst K, et al. Genotype-dependent effects of COMT inhibition on cognitive function in a highly specific, novel mouse model of altered COMT activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:3060–9.

Fiocco AJ, Lindquist K, Ferrell R, Li R, Simonsick EM, Nalls M, et al. COMT genotype and cognitive function: an 8-year longitudinal study in white and black elders. Neurology. 2010;74:1296–302.

Wang Y, Li J, Chen C, Chen C, Zhu B, Moysis RK, et al. COMT rs4680 Met is not always the ‘smart allele’: Val allele is associated with better working memory and larger hippocampal volume in healthy Chinese. Genes Brain Behav. 2013;12:323–9.

Small BJ, Rawson KS, Walsh E, Jim HSL, Hughes TF, Iser L, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype modulates cancer treatment-related cognitive deficits in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:1369–76.

Nagel IE, Chicherio C, Li S-C, Oertzen T, Sander T, Villringer A, et al. Human aging magnifies genetic effects on executive functioning and working memory. Front Hum Neurosci. 2008;2. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.001.2008.

Acknowledgements

CHG is a member of the European Reference Network on Rare Endocrine Conditions (ENDO-ERN), Project ID number 739543.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Aase & Ejnar Danielsens Fond; Fabrikant Einar Willumsens Mindelegat; Fonden for Laegevidenskabens fremme; and C.C. Klestrup & hustru Henriette Klestrups Mindelegat.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by The Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for Central Denmark Region (No. 1-10-72-406-17). The data were collected and stored in accordance with the Danish Data Protection Agency guidelines, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants upon enrollment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buskbjerg, C.R., Amidi, A., Buus, S. et al. Androgen deprivation therapy and cognitive decline—associations with brain connectomes, endocrine status, and risk genotypes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 25, 208–218 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-021-00398-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-021-00398-1

This article is cited by

-

Treatment-Related Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Prostate Cancer: Patients’ Real-World Insights for Optimizing Outcomes

Advances in Therapy (2024)

-

Assessment and Management of Cognitive Function in Patients with Prostate Cancer Treated with Second-Generation Androgen Receptor Pathway Inhibitors

CNS Drugs (2022)

-

Prostate cancer treatment and the relationship of androgen deprivation therapy to cognitive function

Clinical and Translational Oncology (2021)