Abstract

Background

The objectives of this study were to derive trajectories of childhood participation in organized physical activity (PA) and to examine how these trajectories are associated with pre-existing and subsequent emotional adjustment.

Methods

Trajectories of mother-reported participation in organized PA were derived from age 6 to 10 for 1492 children from the Québec Longitudinal Study of Child Development birth cohort. Parents and teachers reported on internalizing behavior (emotional distress, anxiety, shyness, social withdrawal) at ages 4 and 12, respectively.

Results

Longitudinal latent class analysis identified two typical trajectories of participation in organized PA. The Consistent Participation trajectory (61%) included children with elevated probability of participation at all ages. The Low-Inconsistent Participation trajectory (39%) included children who did not participate or participated only once or twice, generally in late childhood. Pre-existing internalizing behavior at age 4 did not predict trajectory membership. However, children in the Low-Inconsistent Participation trajectory showed higher subsequent emotional distress (B = 0.87, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.46–1.28), anxiety (B = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.18–1.04), shyness (B = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.39–1.44), and social withdrawal (B = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.37–1.34) at age 12 than those in the Consistent Participation trajectory.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that early and sustained involvement in organized PA is beneficial for children’s emotional development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Participation in sport and other forms of organized physical activity (PA) may promote positive child development.1 Compared to their more sedentary counterparts, children involved in organized PA tend to experience fewer internalizing behavior.2 These children typically show less anxious and depressive symptoms,3,4,5 as well as social inhibition and shyness.6,7

Three general mechanisms could explain these observations. First, participation in organized PA could buffer against emotional difficulties in children. This could involve positive biological effects of being active, such as improved HPA axis functioning or monoamine neurotransmission8 and/or psycho-social benefits of a supportive organized context, such as opportunities for developing life skills with prosocial peers and adults.1,2 Second, internalizing behavior could reduce participation in organized PA. Children who are shy, fearful, or easily distressed may seek to avoid the social demands of specific venues. Their parents may refrain from enrolling them in activities to protect them from stress, or failure.9 Third, the association between participation in organized PA and internalizing behavior could result from pre-existing family characteristics. For instance, growing up in a dysfunctional family could simultaneously reduce the likelihood of participating in organized activities and increase the risk that children develop internalizing behavior.10

Evidence regarding these mechanisms is limited. Most previous studies have been cross-sectional2 and could not determine directionality in associations. Existing longitudinal studies have been primarily unidirectional. These studies have shown participation in organized PA to predict lower internalizing behavior in children11,12,13 and, in one instance, internalizing behavior to predict lower sport participation.14 This supports the possibility of bidirectional associations, which have been observed in adolescents.11,14,15,16,17,18,19 However, to our knowledge, no study has tested bidirectional associations between participation in organized PA and internalizing behavior in children.

From a developmental point of view, the predictors and outcomes of participation in organized PA are expected to diverge in children who have different trajectories of involvement over time. The psycho-social benefits of sport participation have been argued to be enhanced when participation is sustained.20 Participation in organized PA could also be more beneficial at specific moments, such as transition periods (e.g., school entry), because it supports social integration and the development of transferable skills.

Previous studies support the existence of distinct trajectories of participation in organized PA over childhood and adolescence.21,22,23,24 Collectively, these studies identified three main trajectories: a class of children who consistently partake in organized PA (25–60%), a class of children with consistently low participation (14–40%), and a class with discontinuation over time, which typically occurs after childhood (30–40%). Research has yet to examine internalizing behavior as predictor, correlate or outcome of trajectories of organized PA in children, although consistently high PA (organized or non-organized) has been associated with lower depressive symptoms in adults.22,25

In this study, we analyze data from a population-based cohort to examine the relation between childhood participation in organized PA and internalizing behavior. Our first objective is to identify trajectories of participation in organized PA from ages 6 to 10. Based on previous studies, we expect to find trajectories of consistently high and low participation. We do not expect to find a third trajectory of discontinuation because discontinuation has typically been reported to occur after childhood.26 Our second objective is to examine how trajectories relate to internalizing behavior, including emotional distress, anxiety, shyness, and social withdrawal. We test internalizing behavior as predictor (age 4) and outcome (age 12). We expect the trajectory of consistently high participation in organized PA to be associated with lower internalizing behavior at age 4 and 12 relative to the consistently low participation trajectory, above and beyond potential confounders.

Methods

Participants

Participants took part in the Québec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD). The QLSCD birth cohort initially included 2837 children born between spring 1997 and spring 1998 in Quebec, Canada. Babies were selected using random sampling, stratified by provincial region. From this original selection, 2120 children (82%) were included and followed up, based on parental consent and exclusion criteria. Participants were not retained if they had First Nation status (93) were untraceable (186), or did not receive parental consent to participate (438). Free and informed parental consent was obtained for included children. The study was coordinated by the Institut de la Statistique du Québec and received approval from its Institutional Review Board.

In this study, we used the subsample of 1492 children who were retained by age 6, with sampling weights derived for this subsample. We measured organized PA during childhood (ages 6, 7, 8, and 10) and internalizing behavior at ages 4 and 12 (2002–2010). Rates of missing data ranged from 18 to 22% for participation in organized PA at ages 7, 8, and 10 years: 0–5% for predictors at age 4 and 40–42% for outcomes at age 12. Missing data analysis is presented in Table S1. Data were analyzed in 2018.

Measurement of past-year participation in organized PA (age 6, 7, 8, and 10)

At ages 6, 7, and 8, mothers completed two items: “In the last 12 months, outside of school hours, how often has your child… (a) taken part in sports with a coach or instructor (except dance or gymnastics)?, (b) taken lessons or instruction in other organized physical activities with a coach or instructor such as dance, gymnastics, martial arts or circus arts?” (0 = never, 1 = roughly once a month, 2 = roughly once a week, 3 = several times a week, 4 = roughly every day, 5 = 1 session, 6 = 2 sessions). We computed past-year participation in organized PA as 0 = never and 1 = any participation (item a and/or b ≥1). At age 10, mothers completed 3 items: “How many times a week has your child participated… (a) in organized sport or PA with a coach last summer,” (b) “in organized sport or PA with a coach at school since last September, outside of physical education classes,” and (c) “in organized sport or PA with a coach outside of school since last September” (0 = never, 1 = less than once a week, 2 = once a week, 3 = twice a week, 4 = three times a week, 5 = four times a week, 6 = five times a week or more). We computed part-year participation in organized PA as 0 = never and 1 = any participation (items a, b, and/or c ≥1).

Measurement of internalizing behavior at ages 4 and 12

We examined four scales of internalizing behavior in children: emotional distress, anxiety, shyness, and withdrawal. Items for these scales were selected from previous population-based surveys,27,28 the Social Behavior Questionnaire,29 and the Preschool Behavior Questionnaire.30 Items were reported by mothers and father/partner at age 4 and by the child’s teacher at age 12. Items at age 4 had the following form: “In the past 3 months, how often has your child… [e.g., felt unhappy?].” Items answered by teachers at age 12 had the following form: “In the past 6 months, the child… [e.g., felt unhappy].” Response choices were: 1 = never/untrue, 2 = sometimes/a little true, and 3 = often/very true.

The emotional distress scale included items such as “was less happy than other children” at age 4 (4 items; α = 0.61) and at age 12 (5 items; α = 0.79). The anxiety scale was measured using a 4-item scale (e.g., “was too fearful or anxious”) at age 4 (α = 0.67) and age 12 (α = 0.76). The shyness scale included items such as “has been shy with children that he or she does not know” at age 4 (3 items; α = 0.78) and age 12 (4 items; α = 0.71). The withdrawal scale included items such as “had a tendency to do things alone” at age 4 (3 items; α = 0.70) and age 12 (4 items; α = 0.70). These internalizing behavior scales have been shown to correlate with diagnoses of emotional disorder in childhood28 and correlate with child ratings of depressive symptoms from the Child Depression Inventory31 in the QLSCD (emotional disorder r = 0.25; anxiety r = 0.16; shyness r = 0.11; social withdrawal r = 0.23).

Measurement of potential confounders in early childhood

These included family structure (0 = intact, 1 = non-intact); parental education (highest degree obtained by mother or father: 0 = no high school diploma; 1 = high school diploma or higher); and family income (0 = sufficient; 1 = insufficient), as defined by the Canadian low-income cut-off of that year provided by Statistics Canada. We also included a mother-reported measure of family functioning10 when the child was 17 months old (12 items; α = 0.84). We also controlled for baseline internalizing behavior at age 4 when examining associations between trajectories and internalizing behavior at age 12.

Data analysis

We used longitudinal latent class analysis in Mplus 7.132 to derive trajectories of participation in organized PA from age 6 to 10. We tested models with 1 to 4 classes without predictors and outcomes. We used 5000 start values with 100 optimizations to avoid local maxima, and considered multiple criteria to select the best solution including information criteria, likelihood ratio tests testing the improvement of solutions with k classes vs. k − 1 classes, and substantive interest.33 Models did not converge beyond four classes.

We tested associations between internalizing behavior at age 4 and trajectories using the Mplus R3STEP option. We tested the association between trajectories and internalizing behavior at age 12 using the manual three-step approach.34 We regressed each internalizing outcome on its baseline value and potential confounders at age 4, using the MODEL CONSTRAINT option to compare adjusted mean differences between trajectory groups. We took missing data into account using maximum likelihood estimation except for missing data on predictor variables, which required the use of multiple imputation for the R3STEP option. Analyses were conducted with 20 imputed datasets.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics relative to participation in organized PA and internalizing behavior in participants. The majority of children in the sample participated in organized PA, with rates increasing from 60 to 80% between ages 6 and 10. Emotional distress increased slightly between ages 4 and 12, while shyness and withdrawal decreased. Anxiety scores remained stable over time.

Identification of trajectories of organized PA

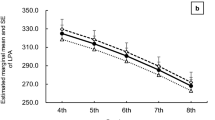

Table 2 reports fit and likelihood ratio tests for different trajectory solutions. Selection of a best model was relatively unambiguous in this case. Information criteria and likelihood ratio tests showed drastic improvement from a one- to two-class model, but no improvement in models with three or four trajectories. Furthermore, while a model with two trajectories showed substantive differentiation between groups, the additional trajectories in models with three or four trajectories could not be meaningfully differentiated. We thus selected the two-class model.

The two identified trajectories are presented in Fig. 1. Class 1 contained 61% of the sample and showed elevated probability of participation at all ages (>85%). On average, children in this trajectory participated in organized PA at 3.6 time points out of a possibility of 4. We labeled this class “Consistent Participation.” Class 2 contained 39% of children and showed low probability of participation in organized PA at ages 6 and 7 (<30%), and slightly higher probability at ages 8 and 10 (42–55%). On average, children in this trajectory participated in organized PA at 1.3 time points out of 4. We labeled this class “Low-Inconsistent Participation.”

Internalizing behavior at age 4 as predictor of trajectories

We next examined associations between internalizing behavior, as reported by parents at age 4, and subsequent trajectories of organized PA. Trajectory membership was not predicted by emotional distress (B[1 SD increase] = 1.06, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.93–1.22), anxiety (B[1 SD increase] = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.93–1.22), shyness (B[1 SD increase] = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.93–1.25) or withdrawal (B[1 SD increase] = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.98–1.34).

Internalizing behavior at age 12 as outcome of trajectories

We then proceeded to examining associations between trajectories and subsequent internalizing behavior, as reported by teachers at age 12. As documented in Table 3, membership in the Low-Inconsistent Participation trajectory was associated with more frequent internalizing behavior at age 12. These associations remained after controlling for statistically significant confounders. Standardized mean differences between trajectories in adjusted models were in the range of small-to-medium for emotional distress (d = 0.42), anxiety (d = 0.27), shyness (d = 0.39), and withdrawal (d = 0.35).

Ancillary analyses

In ancillary analyses, we tested higher-order constructs of internalizing behavior at age 4 as predictors of trajectories: overall internalizing behavior (28 items, d = 0.80), anxious/depressed behaviors (16 items, d = 0.76), and shy/withdrawn behaviors (12 items, d = 0.77). None of these broadband measures predicted subsequent trajectory membership. We also conducted analyses using internalizing behaviors at age 4 reported specifically by the person who knew the child best (which was the mother in the vast majority of cases) and obtained similar results.

To provide a more stringent test of the association with outcomes at age 12, we tested models with three additional controls: (1) body mass index (BMI) at age 4, based on height/weight provided by the primary caregiver, (2) mean mother-reported frequency of participation in non-organized PA (i.e., without a coach) in the past year from age 6 to 10 (0 = no participation to 5 = everyday), and (3) mother-reported cumulative participation in leisure-time organized activities other than PA (0 = no participation, 4 = participation at all time points). The association between trajectories and internalizing outcomes remained significant after including these controls.

Finally, we tested more complex latent class models in which we attempted to consider the frequency of participation in both organized and non-organized PA from age 6 to 10 (Tables S2–S5; Fig. S1). Our approach to variable coding is presented in the Table S2. These analyses produced a similar two-class solution: these classes contained roughly the same proportion of participants, were primarily distinguished by whether or not children participated in organized PA, and showed similar associations with internalizing behavior at age 4 and 12. Thus, even in a more complex model, the consistency of participation in organized PA appeared to be the primary predictor of future emotional adjustment in our data. This result should be, however, interpreted cautiously in light of approximate coding for frequency of participation in organized PA.

Discussion

This study used a population-based cohort to examine prospective associations between trajectories of participation in organized PA and multiple indicators of internalizing behavior across childhood. We identified two trajectories of participation from ages 6 to 10. The most prevalent trajectory (Consistent Participation; 61% of the sample) included children who participated in organized PA at all or almost all ages. The second trajectory (Low-Inconsistent Participation; 39%) included children who were never involved or participated only once or twice. These trajectories were largely consistent with our hypotheses. Previous studies identified these two trajectories of consistently high (25–60%) and low participation (14–40%),21,22,23,24 although a third trajectory was also found with discontinuation after childhood (30–40%). It is likely that our consistent participation trajectory includes a combination of children who will maintain participation and children who will eventually desist from participation after childhood. Rates of participation in organized PA were relatively high in this study, but are consistent with other Canadian data showing that the large majority (77%) of children and adolescents are involved in organized sport, with stable rates over the past 10 to 15 years.35

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no association between parent-reported internalizing behavior at age 4 and subsequent participation in organized PA. This was the case for emotional distress, anxiety, shyness, and social withdrawal taken independently, as well as broadband measures of internalizing symptoms tested in ancillary analyses. Very few studies have tested these associations, except for emotional distress or depressive symptoms, which were found to predict lower general PA in adolescents.15,17,18,36 The discrepancy between our results and those from these studies may be due to developmental changes in determinants of involvement in organized PA. Participation in sport is mostly driven by parents in childhood but becomes increasingly under the control of youth during adolescence.37 Thus, internalizing behavior may emerge as a risk factor after childhood when adolescents are granted greater latitude in deciding whether to maintain or desist their involvement.

Consistent with our hypothesis, we found associations between trajectories and all subsequent teacher-reported internalizing behavior at age 12, including emotional distress (d = 0.42), anxiety (d = 0.27), shyness (d = 0.39), and withdrawal (d = 0.35). These results are consistent with previous longitudinal studies.3,5,11,12,14,38,39 Participation in organized PA may contribute to reducing emotional difficulties in children via biological or psycho-social mechanisms.1,2,8 As discussed in the Positive Youth Development Model, opportunities to develop life skills (e.g., initiative, teamwork, self-control) and relationships with prosocial peers and adults likely play a role when appropriate conditions are put in place.1

A novel contribution of our study was to highlight the importance of the consistency of participation in organized PA for the emotional development of children. Indeed, children who participated at most, if not all, time points in our study showed lower internalizing behavior than children who did not participate or participated inconsistently, which were classified together. Furthermore, ancillary analyses showed that trajectory classes remained similar when modeled based on the joint frequency of participation in organized and non-organized PA. Children remained primarily distinguished in terms of whether or not they participated regularly in organized PA (at least once weekly). Taken together, these results suggest that the consistency of participation in organized PA was the primary PA-related determinant of future internalizing behavior in the sample.

To our knowledge, this prospective population-based study was the first to investigate trajectories of participation in organized PA during childhood and to examine bidirectional associations with internalizing behavior. However, this study is not without limitations. First, measures of participation in PA were derived from mother-reported data with few details. The frequency of participation in organized PA could not be coded unambiguously, which lead us to dichotomize the measure. More detailed, objective measures would have reinforced conclusions regarding the most important aspects of PA that predict emotional outcomes. Second, the reliability of parent-reported measures of internalizing behavior at age 4 was lower than the reliability of child-reported measures at age 12, especially for emotional distress. Parents may not have been able or willing to report reliably on the internalizing symptoms of their child at that age. However, results remained similar when we tested broadband measures of internalizing behavior with higher reliability. Third, attrition was elevated in the sample and may have influenced associations, although our use of maximum likelihood estimation/multiple imputation should have reduced the risk of bias. Fourth, the observational design used in this study does not allow to determine whether the association between participation in organized PA and behavior is causal. Non-measured predisposing factors could lead children to develop internalizing behavior and self-select away from organized PA.

This study raises interesting questions for future investigations. One question is whether the pattern of results that we observed here also applies to other aspects of psycho-social development, such as externalizing behavior. Another question pertains to the transition into adolescence for the classes that were identified. Children with low involvement in organized PA should remain on a similar trajectory over time, but the consistent participation trajectory might eventually split in a group that desists after childhood. Future studies should test this prediction and examine whether and how internalizing behavior relate to this developmental transition—if it indeed occurs.

Consistent with previous reviews,2 our study suggests that childhood participation in organized venues that demand physical skill and effort may represent a valuable strategy to promote both physical and mental health in children. Our study supports public health efforts to promote and facilitate the early and sustained enrollment of children in sport and other organized active leisure, notably by removing financial and other barriers experienced by parents.40

References

Holt, N. L. Positive Youth Development Through Sport 2nd edn (Routledge, London, 2016).

Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J. & Payne, W. R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 10, 98 (2013).

Findlay, L. C. & Coplan, R. J. Come out and play: shyness in childhood and the benefits of organized sports participation. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 40, 153–161 (2008).

Harrison, P. A. & Narayan, G. Differences in behavior, psychological factors, and environmental factors associated with participation in school sports and other activities in adolescence. J. Sch. Health 73, 113–120 (2003).

Wang, M. T., Chow, A. & Amemiya, J. Who wants to play? Sport motivation trajectories, sport participation, and the development of depressive symptoms. J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 1982–1998 (2017).

Dimech, A. S. & Seiler, R. The association between extra-curricular sport participation and social anxiety symptoms in children. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 4, 191–203 (2010).

McHale, J. P. et al. Patterns of personal and social adjustment among sport-involved and noninvolved urban middle-school children. Socio. Sport J. 22, 119–136 (2005).

aan het Rot, M., Collins, K. A. & Fitterling, H. L. Physical exercise and depression. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 76, 204–214 (2009).

Sicouri, G. et al. Parent-child interactions in children with asthma and anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 97, 242–251 (2017).

Pagani, L. S., Japel, C., Vaillancourt, T., Côté, S. & Tremblay, R. E. Links between life course trajectories of family dysfunction and anxiety during middle childhood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 36, 41–53 (2008).

Brière, F. N. et al. Prospective associations between sport participation and psychological adjustment in adolescents. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 575–581 (2018).

Dimech, A. S. & Seiler, R. Extra-curricular sport participation: a potential buffer against social anxiety symptoms in primary school children. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 12, 347–354 (2011).

Gore, S., Farrell, F. & Gordon, J. Sports involvement as protection against depressed mood. J. Res. Adolesc. 11, 119–130 (2001).

Piché, G., Fitzpatrick, C. & Pagani, L. S. Kindergarten self‐regulation as a predictor of body mass index and sports participation in fourth grade students. Mind Brain Educ. 6, 19–26 (2012).

Jerstad, S. J., Boutelle, K. N., Ness, K. K. & Stice, E. Prospective reciprocal relations between physical activity and depression in female adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 78, 268–272 (2010).

Piché, G., Fitzpatrick, C. & Pagani, L. S. Associations between extracurricular activity and self-regulation: a longitudinal study from 5 to 10 years of age. Am. J. Health Promot. 30, e32–e40 (2015).

Stavrakakis, N., de Jonge, P., Ormel, J. & Oldehinkel, A. J. Bidirectional prospective associations between physical activity and depressive symptoms. The TRAILS study. J. Adolesc. Health 50, 503–508 (2012).

Vella, S. A., Swann, C., Allen, M. S., Schweickle, M. J. & Magee, C. A. Bidirectional associations between sport involvement and mental health in adolescence. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 49, 687–694 (2017).

Zahl, T., Steinsbekk, S. & Wichstrom, L. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and symptoms of major depression in middle childhood. Pediatrics 139, e20161711 (2017).

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A. & Weissberg, R. P. Promoting positive youth development through school‐based social and emotional learning interventions: a meta‐analysis of follow‐up effects. Child Dev. 88, 1156–1171 (2017).

Findlay, L. C., Garner, R. E. & Kohen, D. E. Children’s organized physical activity patterns from childhood into adolescence. J. Phys. Act. Health 6, 708–715 (2009).

Howie, E. K., McVeigh, J. A., Smith, A. J. & Straker, L. M. Organized sport trajectories from childhood to adolescence and health associations. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 48, 1331–1339 (2016).

Kwon, S., Janz, K. F., Letuchy, E. M., Burns, T. L. & Levy, S. M. Developmental trajectories of physical activity, sports, and television viewing during childhood to young adulthood: Iowa Bone Development Study. JAMA Pediatr. 169, 666–672 (2015).

Kwon, S., Janz, K. F., Letuchy, E. M., Burns, T. L. & Levy, S. M. Parental characteristic patterns associated with maintaining healthy physical activity behavior during childhood and adolescence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 13, 58 (2016).

McKercher, C. et al. Physical activity patterns and risk of depression in young adulthood: a 20-year cohort study since childhood. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 49, 1823–1834 (2014).

Caspersen, C. J., Pereira, M. A. & Curran, K. M. Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 32, 1601–1609 (2000).

Statistics Canada. National Longidutinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY). http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=3513. Accessed 31 March 2019.

Boyle, M. H. et al. Evaluation of the original Ontario child health study scales. Can. J. Psychiatry 38, 397–405 (1993).

Tremblay, R. E. et al. Disruptive boys with stable and unstable high fighting behavior patterns during junior elementary school. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 19, 285–300 (1991).

Behar, L. B. & Stringfield, S. A behavior rating scale for the preschool child. Dev. Psychol. 10, 601–610 (1974).

Kovacs, M. Children’s depression inventory: Manual (Multi-Health Systems, North Tonawanda, 1992).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide 6th edn (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, 1998).

Muthén, B. O. in Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences (ed. Kaplan, D.) 345–368 (Sage Publications, Newbury Park, 2004).

Asparouhov, T. & Muthén, B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: three-step approaches using Mplus. Struct. Equ. Model. 21, 329–341 (2014).

Institut canadien de la recherche sur la condition physique et le mode de vie. Bulletin 02: Participation à l’activité physique et au sport organisés (Institut canadien de la recherche sur la condition physique et le mode de vie, Ottawa, 2016). http://cri.ca/fr/document/bulletin-02-participation-%C3%A0-l%E2%80%99acti-vit%C3%A9-physique-et-au-sport-organis%C3%A9s. Accessed 1 March 2019.

Gunnell, K. E. et al. Examining the bidirectional relationship between physical activity, screen time, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over time during adolescence. Prev. Med. 88, 147–152 (2016).

Yao, C. A. & Rhodes, R. E. Parental correlates in child and adolescent physical activity: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 12, 10 (2015).

Ashdown-Franks, G., Sabiston, C. M., Solomon-Krakus, S. & O’Loughlin, J. L. Sport participation in high school and anxiety symptoms in young adulthood. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 12, 19–24 (2017).

Jewett, R. et al. School sport participation during adolescence and mental health in early adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 55, 640–644 (2014).

Holt, N. L., Kingsley, B. C., Tink, L. N. & Scherer, J. Benefits and challenges associated with sport participation by children and parents from low-income families. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 12, 490–499 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This study was specifically supported by a secondary data analytic grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC-435‐2017‐0784 [awarded to F.N.B.]). The larger Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD) is coordinated by the Institut de la Statistique du Québec and is made possible owing to the funding provided by the Fondation Lucie et André Chagnon, the Institut de la Statistique du Québec, the Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement Supérieur (MEES), the Ministère de la Famille (MF), the Institut de recherche Robert Sauvé en santé et sécurité au travail (IRSST), the Centre hospitalier universitaire Ste-Justine, and the Ministère de la Santé et des services sociaux (MSSS). Source: Data compiled from the final master file “E1–E20” from the QLSCD (1998–2017). The sponsors did not influence study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.N.B. conducted data analyses and played the primary role in conceptualizing the study and writing the manuscript. All authors (1) contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, as well as interpretation of data; (2) contributed substantially to drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brière, F.N., Imbeault, A., Goldfield, G.S. et al. Consistent participation in organized physical activity predicts emotional adjustment in children. Pediatr Res 88, 125–130 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0417-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0417-5

This article is cited by

-

Impact of player preparation on effective sports management: parent’s perspective

International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management (2023)

-

Injuries in Canadian high school boys’ collision sports: insights across football, ice hockey, lacrosse, and rugby

Sport Sciences for Health (2023)