Abstract

Background

Despite the health benefits of urban green space, disparities in its access and use have long existed. Emerging evidence suggests an adverse impact of redlining, a discriminatory practice decades ago, on multiple health outcomes. However, whether and to what degree redlining contributes to these disparities remains unknown particularly during a pandemic. With newly available mobility data tracking the locations of large numbers of mobile devices, this study links historical redlining with changes in green space use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective

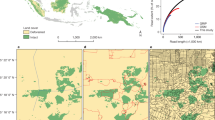

This study examines how changes in park visits during the lockdown period (3/23/2020–8/2/2020) are associated with redlining across census tracts in three large U.S. cities.

Methods

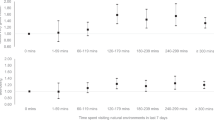

HOLC neighborhood redlining grade data were merged with SafeGraph mobility data at census tract level for New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia. Ordinary Least Square regressions were conducted to assess the association between dominant redlining grade and relative change in park visits in census tracts by comparing the lockdown period to the reference period. Spatial error and lag models were also used to account for potential spatial autocorrelation.

Results

Park visits during the lockdown period in 2020 decreased by at least one-third in the three cities. The influence of redlining varied across neighborhoods and cities. In New York City, neighborhoods with more redlined areas experienced the largest drop, sharper decreases concentrated in neighborhoods previously graded as “best” or “still desirable” in Philadelphia, but the effect was barely present in Chicago. In addition, changes in park visits are positively correlated between neighborhoods in New York City and Chicago, but it’s not observed in Philadelphia.

Impact Statement

-

Using emerging big mobility data, our study revealed large drops in park visits, a better measure than commonly-used access measures in capturing green space exposure, during the lockdown period. We found that historical redlining has a lasting impact on current green space use. More decreases in park visits were observed in the redlined areas in New York City, but patterns vary by neighborhood and city due to local-specific neighborhood dynamics. And changes in park visits were spatially, positively correlated across places.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pinto LV, Inácio M, Ferreira CSS, Ferreira AD, Pereira P. Ecosystem services and well-being dimensions related to urban green spaces – A systematic review. Sustain Cities Soc. 2022;85:104072.

Fong KC, Hart JE, James P. A review of epidemiologic studies on greenness and health: updated literature through 2017. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2018;5:77–87.

James P, Banay RF, Hart JE, Laden F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2015;2:131–42.

Twohig-Bennett C, Jones A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ Res 2018;166:628–37.

Liu H, Li F, Li J, Zhang Y. The relationships between urban parks, residents’ physical activity, and mental health benefits: A case study from Beijing, China. J Environ Manag. 2017;190:223–30.

Banay RF, Bezold CP, James P, Hart JE, Laden F. Residential greenness: Current perspectives on its impact on maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Women’s Health. 2017;9:133.

Crouse DL, Pinault L, Balram A, Hystad P, Peters PA, Chen H, et al. Urban greenness and mortality in Canada’s largest cities: A national cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1:e289–97.

James P, Hart JE, Banay RF, Laden F. Exposure to greenness and mortality in a nationwide prospective cohort study of women. Environ Health Perspect, 2016;124:1344–52.

Vienneau D, de Hoogh K, Faeh D, Kaufmann M, Wunderli JM, Röösli M, et al. More than clean air and tranquillity: residential green is independently associated with decreasing mortality. Environ Int. 2017;108:176–84.

Camargo DM, Ramírez PC, Fermino RC. Individual and environmental correlates to quality of life in park users in Colombia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1250.

Sharifi F, Nygaard A, Stone WM. Heterogeneity in the subjective well-being impact of access to urban green space. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021;74:103244.

Ambrey CL, Shahni TJ. Greenspace and wellbeing in Tehran: A relationship conditional on a neighbourhood’s crime rate? Urban For. Urban Green 2017;27:155–61.

Scopelliti M, Carrus G, Adinolfi C, Suarez G, Colangelo G, Lafortezza R, et al. Staying in touch with nature and well-being in different income groups: The experience of urban parks in Bogotá. Landsc Urban Plan 2016;148:139–48.

Boone CG, Buckley GL, Grove JM, Sister C. Parks and people: An environmental justice inquiry in Baltimore, Maryland. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2009;99:767–87.

Rigolon A. A complex landscape of inequity in access to urban parks: A literature review. Landsc Urban Plan 2016;153:160–9.

Wolch J, Wilson JP, Fehrenbach J. Parks and park funding in Los Angeles: An equity-mapping analysis. Urban Geogr. 2005;26:4–35.

Casey JA, James P, Cushing L, Jesdale BM, Morello-Frosch R. Race, ethnicity, income concentration and 10-year change in urban greenness in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1546.

Mayen Huerta C, Cafagna G. Snapshot of the Use of Urban Green Spaces in Mexico City during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:4304.

Jay J, Heykoop F, Hwang L, de Jong J, Kondo M. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Park Use in U.S. Cities. medRxiv. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.23.21256007.

Ugolini F, Massetti L, Pearlmutter D, Sanesi G. Usage of urban green space and related feelings of deprivation during the COVID-19 lockdown: Lessons learned from an Italian case study. Land Use Policy. 2021;105:105437.

Venter ZS, Barton DN, Gundersen V, Figari H, Nowell MS. Back to nature: Norwegians sustain increased recreational use of urban green space months after the COVID-19 outbreak. Landsc Urban Plan 2021;214:104175.

Geng DC, Innes J, Wu W, Wang G. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on urban park visitation: a global analysis. J Res 2021;32:553–67.

Larson LR, Zhang Z, Oh JI, Beam W, Ogletree SS, Bocarro JN, et al. Urban Park Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Are Socially Vulnerable Communities Disproportionately Impacted? Front. Sustain. Cities. 2021;3:710243.

Taff BD, Rice WL, Lawhon B, Newman P. Who Started, Stopped, and Continued Participating in Outdoor Recreation during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States? Results from a National Panel Study. Land. 2021;10:1396.

Nardone A, Chiang J, Corburn J. Historic Redlining and Urban Health Today in U.S. Cities. Environ. Justice. 2020;13:109–19.

Hillier AE. Redlining and the home owners’ loan corporation. J Urban Hist. 2003;29:394–420.

Greer J. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the Development of the Residential Security Maps. J Urban Hist 2013;39:275–96.

Mitchell B, Franco J. HOLC “redlining” maps: the persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality. 2018. Available online at: http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/dsp01dj52w776n. Accessed 21 Oct 2021.

Lee EK, Donley G, Ciesielski TH, Gill I, Yamoah O, Roche A, et al. Health outcomes in redlined versus non-redlined neighborhoods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 2022;294:114696.

Bertocchi G, Dimico A. COVID-19, race, and redlining. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.11.20148486.

Li M, Yuan F. Historical redlining and food environments: A study of 102 urban areas in the United States. Health Place. 2022;75:102775.

Chang S, Pierson E, Koh PW, Gerardin J, Redbird B, Grusky D, et al. Mobility network models of COVID-19 explain inequities and inform reopening. Nature. 2021;589:82–7.

Nardone A, Rudolph KE, Morello-Frosch R, Casey JA. Redlines and Greenspace: The Relationship between Historical Redlining and 2010 Greenspace across the United States. Environ Health Perspect 2021;129:017006.

SafeGraph. What about bias in the Safegraph dataset? 2022. Available online at: https://www.safegraph.com/blog/what-about-bias-in-the-safegraph-dataset. Accessed 3 Jan 2022.

SafeGraph. Guide to Points-of-Interest Data: POI Data FAQ. 2022. Available online at: https://www.safegraph.com/points-of-interest-poi-data-guide. Accessed 3 Jan 2022.

Funding

This research is supported by the University at Albany President’s COVID-19 and Minority Health Disparities Seed Funding Program [88826-1-1162929, 2021] and the American Heart Association (grant 19TPA34830085).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - original draft; YH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology; RL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources; KZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Huang, Y., Li, R. et al. Historical redlining and park use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from big mobility data. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-023-00569-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-023-00569-3