Abstract

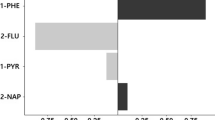

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a group of compounds formed during the incomplete combustion of organic matter. Several are mutagenic carcinogens; the magnitude of exposure can be assessed by examining urinary levels of PAH metabolites. Data from biomonitoring studies that record urinary PAH metabolite levels, as well as demographic and lifestyle information, can be used to investigate relationships between PAH exposure and variables, such as smoking status, workplace smoking restrictions, age, sex, household income, home age, and occupation. This study analysed creatinine-adjusted urinary PAH metabolite concentrations and questionnaire data from ~1200 individuals aged 16 years and older surveyed in Cycle 2 of the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS). Statistical analyses revealed that smoking status, age, and sex are associated with urinary concentrations of a pyrene metabolite (1-OHP), phenanthrene metabolites (ΣOH-Phen), fluorene metabolites (ΣOH-Flu) and naphthalene metabolites (ΣOH-Nap). More specifically, smoking status, age and sex can collectively account for 30, 24, 52, and 34% of the observed variations in 1-OHP, ΣOH-Phen, ΣOH-Flu and ΣOH-Nap metabolites, respectively (p < 0.001). Analyses of non-smokers revealed weak but significant effects of age, sex, home age, and occupation on urinary levels of selected PAH metabolites (i.e., <7% of observed variation, p < 0.05). The unexplained variation in PAH metabolite levels is most likely related to diet, which was not examined. Although the results revealed significant relationships between urinary PAH metabolite levels and several lifestyle and/or demographic variables, robust examinations of selected effects (e.g., sex, home age, occupation) will require datasets that are balanced with respect to the other highlighted variables. The results can be used to identify remedial measures to reduce exposure and concomitant risk, and/or design follow-up studies to test hypotheses regarding the causes of exposure differences empirically related to sex, age, home age, and occupation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Goldman R, Enewold L, Pellizzari E, Beach JB, Bowman ED, Krishnan SS, et al. Smoking increases carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human lung tissue. Cancer Res 2001;61:6367–71.

St Helen G, Goniewicz ML, Dempsey D, Wilson M, Jacob PJ, Benowitz NL. Exposure and kinetics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in cigarette smokers. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:952–64.

Ramesh A, Walker SA, Hood DB, Guillen MD, Schneider K, Weyand EH. Bioavailability and risk assessment of orally ingested polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Int J Toxicol. 2004;23:301–33.

Jongeneelen FJ. Biological exposure limit for occupational exposure to coal tar pitch volatiles at cokeovens. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1992;63:511–6.

Jongeneelen FJ. A guidance value of 1-hydroxypyrene in urine in view of acceptable occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxicol Lett 2014;231:239–48.

Jongeneelen FJ. Benchmark guideline for urinary 1-hydroxypyrene as biomarker of occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Ann Occup Hyg. 2001;45:3–13.

Guo Y, Senthilkumar K, Alomirah H, Moon H-B, Minh TB, Mohd MA, et al. Concentrations and profiles of urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites (OH-PAHs) in several Asian countries. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:2932–8.

Ruby MV, Lowney YW, Bunge AL, Roberts SM, Gomez-Eyles JL, Ghosh U, et al. Oral Bioavailability, Bioaccessibility, and Dermal Absorption of PAHs from Soil State of the Science. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:2151–64.

Britz-McKibbin P, Fernando S, Gallea M, VandenEnden L, House R, Verma D, et al. Evaluation of firefighter exposure to wood smoke during training exercises at burn houses. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:1536–43.

Polanska K, Hanke W, Dettbarn G, Sobala W, Gromadzinska J, Magnus P, et al. The determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the urine of non-smoking Polish pregnant women. Sci Total Environ. 2014;487:102–9.

IARC. Painting, firefighting, and shiftwork. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2010;98:9–764.

IARC. Household use of solid fuels and high-temperature frying. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2010;95:1–430.

Abdel-Shafy H, Mansour M. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt J Pet. 2016;25:107–23.

Lemieux C, Long A, Lambert I. In vitro mammalian mutagenicity of complex polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures in contaminated soils. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:1787–96.

Maertens RM, Bailey J, White PA. The mutagenic hazards of settled house dust: a review. Mutat Res Mutat Res 2004;567:401–25.

Whitehead T, Metayer C, Gunier R, Ward M. Determinants of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon levels in house dust. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2011;21:123–32.

Jansen E, Schenk E. Use of biomarkers in exposure assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Clin Chem. 1995;41:1905–6.

Kim H, Cho S, Kang J, Kim Y, Nan H. Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene and 2-naphthol concentrations in male Koreans. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2000;74:59–62.

Serdar B, Waidyanatha S, Zheng Y, Rappaport SM. Simultaneous determination of urinary 1-and 2-naphthols, 3-and 9-phenanthrols, and 1-pyrenol in coke oven workers. Biomarkers 2003;8:93–109.

Haines DA, Saravanabhavan G, Werry K, Khoury C. An overview of human biomonitoring of environmental chemicals in the Canadian Health Measures Survey: 2007–2019. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017;220:13–28.

Haines DA, Murray J. Human biomonitoring of environmental chemicals—early results of the 2007–2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey for males and females. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2012;215:133–7.

Bushnik T, Haines D, Levallois P, Levesque J, Van Oostdam J, Viau C. Lead and bisphenol A concentrations in the Canadian population. Health Rep. 2010;21:7–18.

Li Z, Sandau CD, Romanoff LC, Caudill SP, Sjodin A, Needham LL, et al. Concentration and profile of 22 urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites in the US population. Environ Res 2008;107:320–31.

Statistics Canada. Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) Data User Guide: Cycle 2. Ottawa; 2012.

Giroux S. Canadian Health Measures Survey: sampling strategy overview. Health Rep. 2006;18:31–36.

Gaudreau É, Bérubé R, Bienvenu J-F, Fleury N. Stability issues in the determination of 19 urinary (free and conjugated) monohydroxy polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408:4021–33.

Statistics Canada. National Occupational Classification for Statistics (NOC-S) 2001. Vol 2016. 2016. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=65267

Statistics Canada. Low Income Lines, 2009-2010 [Internet]. pp 1–39. 2011. www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75f0002m/75f0002m2011002-eng.pdf. Cited on 27 Sept 2017.

Statistics Canada. Education and occupation of high-income Canadians [Internet]. 2016. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-014-x/99-014-x2011003_2-eng.cfm

Barr DB, Wilder LC, Caudill SP, Gonzalez AJ, Needham LL, Pirkle JL. Urinary creatinine concentrations in the US population: implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:192–200.

Cakmak S, Hebbern C, Cakmak JD, Dales R. The influence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on lung function in a representative sample of the Canadian population. Environ Pollut 2017;228:1–7.

Allison P. When can you safely ignore multicollinearity?. 2012. https://statisticalhorizons.com/multicollinearity. Cited on 18 May 2018.

Schreiber-Gregory D, Jackson HM. Multicollinearity: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and How Can It Be Controlled? In: Proceedings of the SAS® Global Forum 2017. Conference, paper 1404–2017. Cary, NC: SAS. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings17/1404-2017.pdf.

Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985.

Wang F & Shin HC Paper SA-02: SAS® Model Selection Macros for Complex Survey Data Using PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC/SURVEYREG. 2011. http://www.mwsug.org/proceedings/2011/stats/MWSUG-2011-SA02.pdf. Cited on 2 May 2018.

Moir D, Rickert WS, Levasseur G, Larose Y, Maertens R, White P, et al. A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;21:494–502.

US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. p. 17.

IARC. Some non-heterocyclic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some related exposures. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2010;92:1–853.

van Schooten FJ, Jongeneelen FJ, Hillebrand MJ, van Leeuwen FE, de Looff AJ, Dijkmans AP, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts in white blood cell DNA and 1-hydroxypyrene in the urine from aluminum workers: relation with job category and synergistic effect of smoking. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1995;4:69–77.

Benowitz NL, Renner CC, Lanier AP, Tyndale RF, Hatsukami DK, Lindgren B, et al. Exposure to nicotine and carcinogens among Southwestern Alaskan Native cigarette smokers and smokeless tobacco users. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2012;21(Jun):934–42.

Hecht SS. Human urinary carcinogen metabolites: biomarkers for investigating tobacco and cancer. Carcinogenesis 2002;23:907–22.

Levine H, Berman T, Goldsmith R, Göen T, Spungen J, Novack L, et al. Urinary concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Israeli adults: demographic and life-style predictors. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2015;218:123–31.

Strickland P, Kang D. Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene and other PAH metabolites as biomarkers of exposure to environmental PAH in air particulate matter. Toxicol Lett. 1999;108:191–9.

Wei B, Alwis U, Li Z, Wang L, Valentin-Blasini L, Sosnoff CS, et al. Urinary concentrations of PAH and VOC metabolites in marijuana users. Environ Int 2016;88:1–8.

Menzie CA, Potocki BB, Santodonato J. Exposure to carcinogenic PAHs in the environment. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26:1278–84.

Kim C, Gao Y-T, Xiang Y-B, Barone-Adesi F, Zhang Y, Hosgood HD, et al. Home kitchen ventilation, cooking fuels, and lung cancer risk in a prospective cohort of never smoking women in Shanghai, China. Int J Cancer. 2014;136:632–8.

Pan CH, Chan CC, Wu KY. Effects on Chinese restaurant workers of exposure to cooking oil fumes: a cautionary note on urinary 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:3351–7.

Riojas-Rodriguez H, Schilmann A, Marron-Mares AT, Masera O, Li Z, Romanoff L, et al. Impact of the improved patsari biomass stove on urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biomarkers and carbon monoxide exposures in rural Mexican women. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:1301–7.

Rose M, Holland J, Dowding A, Petch SRG, White S, Fernandes A, et al. Investigation into the formation of PAHs in foods prepared in the home to determine the effects of frying, grilling, barbecuing, toasting and roasting. Food Chem Toxicol. 2015;78:1–9.

Tonne CC, Whyatt RM, Camann DE, Perera FP, Kinney PL. Predictors of personal polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposures among pregnant minority women in New York City. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:754–9.

Ben-Zaken Cohen S, Paré PD, Man SFP, Sin DD. The growing burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer in women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:113–20.

Mollerup S, Berge G, Bæra R, Skaug V, Hewer A, Phillips DH, et al. Sex differences in risk of lung cancer: expression of genes in the PAH bioactivation pathway in relation to smoking and bulky DNA adducts. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:741–4.

Vahter M, Berglund M, Åkesson A, Liden C. Metals and women’s health. Environ Res 2002;88:145–55.

Mollerup S, Ryberg D, Hewer A, Phillips DH, Haugen A. Sex differences in lung CYP1A1 expression and DNA adduct levels among lung cancer patients. Cancer Res 1999;59:3317–20.

Chuang JC, Callahan PJ, Lyu CW, Wilson NK. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposures of children in low-income families. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1999;9:85–98.

Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, et al. Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol 1994;49:15.

Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ. Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:269–78.

Emmons KM, Hammond SK, Fava JL, Velicer WF, Evans JL, Monroe AD. A randomized trial to reduce passive smoke exposure in low-income households with young children. Pediatrics 2001;108:18–24.

Sreeramareddy CT, Harper S, Ernstsen L. Educational and wealth inequalities in tobacco use among men and women in 54 low-income and middle-income countries. Tob Control 2016;27:26–34.

Chuang JC, Mack GA, Kuhlman MR, Wilson NK. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives in indoor and outdoor air in an eight-home study. Atmos Environ Part B Urban Atmos. 1991;25:369–80.

Johansson L, Leckner B, Gustavsson L, Cooper D, Tullin C, Potter A. Emission characteristics of modern and old-type residential boilers fired with wood logs and wood pellets. Atmos Environ 2004;25:4183–95.

Gustafson P, Östman C, Sällsten G. Indoor levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in homes with or without wood burning for heating. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:5074–80.

IARC. Chemical agents and related occupations. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100F:1–628.

Lee K, Lim H-S, Kim H. A study of the status of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in relation to its metabolites among workers in a Korean chemical factory. Cien Saude Colet. 2014;19:4809–18.

Peters S, Talaska G, Jonsson BA, Kromhout H, Vermeulen R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure, urinary mutagenicity, and DNA adducts in rubber manufacturing workers. Cancer Epidemiol Prev. Biomarkers 2008;17:1452–9.

Sellappa S, Mani B, Keyan KS. Cytogenetic biomonitoring of road paving workers occupationally exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:713–7.

Simioli P, Lupi S, Gregorio P, Siwinska E, Mielzynska D, Clonfero E, et al. Non-smoking coke oven workers show an occupational PAH exposure-related increase in urinary mutagens. Mutat Res Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2004;562:103–10.

Siwinska E, Mielzynska D, Kapka L. Association between urinary 1-hydroxypyrene and genotoxic effects in coke oven workers. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:1–7.

Tsai P-J, Shieh H-Y, Lee W-J, Lai S-O. Health-risk assessment for workers exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a carbon black manufacturing industry. Sci Total Environ. 2001;278:137–50.

Kamal A, Cincinelli A, Martellini T, Malik R. Linking mobile source-PAHs and biological effects in traffic police officers and drivers in Rawalpindi (Pakistan). Environ Saf. 2016;127:135–43.

Keir JLA, Akhtar US, Matschke DMJ, Kirkham TL, Chan HM, Ayotte P, et al. Elevated exposures to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other organic mutagens in ottawa firefighters participating in emergency, on-shift fire suppression. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:12745–55.

Alexandrie AK, Warholm M, Carstensen U, Axmon A, Hagmar L, Levin JO, et al. CYP1A1 and GSTM1 polymorphisms affect urinary 1-hydroxypyrene levels after PAH exposure. Carcinogenesis 2000;21:669–76.

Bentsen-Farmen RK, Botnen IV, Notø H, Jacob J, Øvrebø S. Detection of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites by high-pressure liquid chromatography after purification on immunoaffinity columns in urine from occupationally exposed workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1999;72:161–8.

Göen T, Gündel J, Schaller K-H, Angerer J. The elimination of 1-hydroxypyrene in the urine of the general population and workers with different occupational exposures to PAH. Sci Total Environ. 1995;163:195–201.

Schoket B, Poirier MC, Mayer G, Török G, Kolozsi-Ringelhann Á, Bognár G, et al. Biomonitoring of human genotoxicity induced by complex occupational exposures. Mutat Res Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 1999;445:193–203.

Bang KM, Kim JH. Prevalence of cigarette smoking by occupation and industry in the United States. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40:233–9.

Siemiatycki J, Wacholder S, Dewar R, Cardis E, Greenwood C, Richardson L. Degree of confounding bias related to smoking, ethnic group, and socioeconomic status in estimates of the associations between occupation and cancer. J Occup Environ Med. 1988;30:617–25.

Bedard D, Shatenstein B, Nadon S. Underreporting of energy intake from a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire completed by adults in Montreal. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:675–81.

Ferrari P, Slimani N, Ciampi A, Trichopoulou A, Naska A, Lauria C, et al. Evaluation of under-and overreporting of energy intake in the 24-hour diet recalls in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(6b):1329–45.

Livingstone MB, Prentice AM, Strain JJ, Coward WA, Black AE, Barker ME, et al. Accuracy of weighed dietary records in studies of diet and health. BMJ 1990;300:708–12.

Schaefer EJ, Augustin JL, Schaefer MM, Rasmussen H, Ordovas JM, Dallal GE, et al. Lack of efficacy of a food-frequency questionnaire in assessing dietary macronutrient intakes in subjects consuming diets of known composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:746–51.

Comino I, Fernández-Bañares F, Esteve M, Ortigosa L, Castillejo G, Fambuena B, et al. Fecal gluten peptides reveal limitations of serological tests and food questionnaires for monitoring gluten-free diet in celiac disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1456–65.

Cakmak S, Dales R, Hebbern C. The association between urinary phthalates and lung function. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56:376.

Ye M, Beach J, Martin J, Senthilselvan A. Associations between dietary factors and urinary concentrations of organophosphate and pyrethroid metabolites in a Canadian general population. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2015;218:616–26.

Middleton DRS, Watts MJ, Lark RM, Milne CJ, Polya DA. Assessing urinary flow rate, creatinine, osmolality and other hydration adjustment methods for urinary biomonitoring using NHANES arsenic, iodine, lead and cadmium data. Environ Heal. 2016;15:68.

Acknowledgements

We thank the support of the University of Ottawa, the CREATE-REACT program of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Ontario Ministry of Labour, and Health Canada Intramural Funding. We are grateful for comments received from two Health Canada internal reviewers and three anonymous peer reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keir, J.L.A., Cakmak, S., Blais, J.M. et al. The influence of demographic and lifestyle factors on urinary levels of PAH metabolites—empirical analyses of Cycle 2 (2009–2011) CHMS data. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 31, 386–397 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-020-0208-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-020-0208-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

E-waste polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) exposure leads to child gut-mucosal inflammation and adaptive immune response

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2021)

-

The Preliminary Study on the Association Between PAHs and Air Pollutants and Microbiota Diversity

Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology (2020)