Abstract

More than 80% of the HIV-infected adolescents live in sub-Saharan Africa. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related mortality has increased among adolescents 10–19 y old. The impact is highest in sub-Saharan Africa, where >80% of HIV-infected adolescents live. The World Health Organization has cited inadequate access to HIV testing and counseling (HTC) as a contributing factor to AIDS-related adolescent deaths, most of which occur in sub-Saharan Africa. This review focuses on studies conducted in high adolescent HIV-burden countries targeted by the “All In to End Adolescent AIDS” initiative, and describes barriers to adolescent HTC uptake and coverage. Fear of stigma and family reaction, fear of the impact of a positive diagnosis, perceived risk with respect to sexual exposure, poor attitudes of healthcare providers, and parental consent requirements are identified as major impediments. Most-at-risk adolescents for HIV infection and missed opportunities for testing include, those perinatally infected, those with early sexual debut, high mobility and multiple/older partners, and pregnant and nonpregnant females. Regional analyses show relatively low adolescent testing rates and more restrictive consent requirements for HTC in West and Central Africa as compared to East and southern Africa. Actionable recommendations for widening adolescent access to HTC and therefore timely care include minimizing legal consent barriers, healthcare provider training, parental education and involvement, and expanding testing beyond healthcare facilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Adolescents 10–19 y old have recently received increased global focus for targeted HIV research and programming. Between 2005 and 2012, AIDS-related deaths fell by 30% among the global people living with HIV (PLHIV) population (1); however mortality rose by 50% among adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) (1,2). Globally, in 2013, an estimated 120,000 AIDS-related deaths occurred among adolescents aged 10–19 y, with 110,000 (nearly 92%) of these deaths occurring in sub-Saharan Africa (3). This represents a significant rise in global adolescent AIDS deaths from 71,000 in 2005 (4).

AIDS is the number one killer of adolescents in Africa (5,6). To control the impact of AIDS on the lives of adolescents living in sub-Saharan Africa, early detection and treatment as well as the prevention of new infections are important. With respect to new infections, female adolescents are of particular concern. In 2013, approximately 65% of all new adolescent HIV infections were among girls, largely in sub-Saharan African countries (3,6). Of the 1.7 million African ALHIV, an estimated 1 million (nearly 60%), are female (7). In countries such as South Africa, Sierra Leone and Gabon, girls represent more than 80% of new HIV infections in adolescents (4,8). Regardless of gender, the vast majority of African adolescents, including those already infected with HIV, do not know their HIV status (3,6). The rates of HIV testing among adolescents range from a low of 1% in Congolese males to 44% in Malawian females, with a 16.4% average testing rate between 18 high-burden African countries (8). Limited access to HIV testing and counseling (HTC), leading to late or limited access to quality care have been cited by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNAIDS as a causative factor in the increase in ALHIV mortality over the past decade (6,9). Therefore, low rates of testing, especially in the highest adolescent HIV-burden countries should be evaluated, and barriers to wider access to testing-and therefore to early treatment and treatment-as-prevention- should be effectively addressed.

In February 2015, the United Nations launched the “All-In” initiative to end Adolescent AIDs, which aims to reduce new adolescent infections by 75%, to reduce AIDS-related mortality by 65%, and to achieve zero discrimination by 2020 (8). Of the 25 “All In” countries that represent 90% of deaths and 85% of new infections in adolescents, 18 (72%) are in sub-Saharan Africa (8). “All In” aims for at least 90% of ALHIV to know their status, and part of the approach is to advocate for wider adolescent access to HIV testing at the country level using strategic information relevant to this population (8). Unfortunately, without concentrated efforts, sub-Saharan Africa may be left behind and may not meet this target by 2020. This review highlights region-specific adolescent HIV studies and discusses challenges in, and opportunities for providing wider access to timely HTC services for adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa.

Uptake of Adolescent HIV Testing and Counseling in Sub-Saharan Africa

In 2007, the WHO recommended provider-initiated testing and counseling (PITC) as an opt-out approach to HTC, where healthcare workers provide testing as part of routine medical care or clinical management unless the client declines (10). This was in contrast to the client-initiated voluntary counseling and testing, where the client proactively seeks HIV testing on their own. The goal of the PITC strategy is to increase opportunities for HIV testing and diagnosis, especially in high-burden areas with low testing rates. With the PITC guidelines came a recommendation to governments “to develop and implement clear legal and policy frameworks” to address issues of consent and assent for minors including adolescents (10). Even for client-initiated voluntary counseling and testing, issues of consent and assent remain for adolescent minors, and therefore the presence of clear, well-communicated legal policies play a critical role in HTC scale-up among adolescents.

By 2010, 42 African countries, including all 18 All-In African countries, had adopted a PITC policy, however, the PITC policies were not universally applied across all populations in all countries (11). The main population targeted was pregnant women, and by 2010, only 31 of the 42 countries offered PITC to all adults, and PITC was offered to infants of HIV-positive mothers, children on admission or in feeding centers in only 10 countries (11).

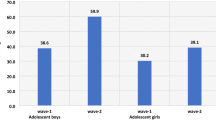

Table 1 shows rates of HIV testing among adolescents who also received their results in the 18 All-In African countries, using the most current available data between 2009 and 2014. Among girls, the lowest rates were in Nigeria (4%), the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (5%) and Côte d’Ivoire (10%), while the highest rates occurred in Uganda (31%), Lesotho (33%), and Malawi (44%). For boys, testing rates were lowest in the DRC (1%), Nigeria (2%), and Côte d’Ivoire (5%) and highest in Swaziland (18%), Malawi (21%), and Rwanda (24%) (8). These data reveal that the lowest HIV testing rates among adolescents are occurring in West and Central African (WCA) countries, while the highest rates are in East and southern African (ESA) countries. It is possible that the relatively lower rates of adolescent HTC in WCA countries stem from the prevalence and/or type of epidemic in that region. Adult HIV prevalence in WCA countries (median 1.6%) is generally lower than in ESA countries (median 6.3%) (12). Furthermore, in contrast to ESA’s generalized epidemic, WCA presents more of a mixed (both generalized and concentrated) epidemic within countries (13). This may make it more complicated to locate and test HIV-infected individuals, and therefore result in lower HTC coverage. Regardless, none of the adolescent HTC rates in any African country approximate the 90% target that the All-In initiative aims for. While also falling short of the 90% benchmark, reported adult (15–49 y) HTC in the All-In countries have been higher than that of adolescents. Drawing on data current between 2010 and 2013, adult HTC rates were 12.6, 13.2, and 17.1% in Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, and Nigeria, respectively; higher values of 59.3% were reported from Uganda, 63.8% from Botswana and 51.2%/71.6% (in males/females) from Malawi (14). Similar to the adolescent group, WCA adults are experiencing the lowest HTC rates while those in ESA countries are experiencing relatively higher rates. The WHO PITC, Adolescent Testing and Consolidated HIV Testing Service guidelines make testing recommendations for all populations in low-level, concentrated and generalized epidemics, but not specifically for mixed concentrated-generalized epidemics (9,10,15). All populations are to be offered PITC in generalized epidemics, and key population adolescents are to be offered testing in all epidemic type settings (9,10,15). Testing services with linkage to care are to be made accessible for adolescents in concentrated and low-level epidemic settings (9,15). All three documents strongly recommend revision of age of consent policies to increase independent access to HTC for adolescents.

Willingness to Test and Barriers to HIV Testing and Counseling Among Adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa

Studies show that the desire to be tested for HIV among adolescents is relatively high. A WHO study combining data from workshops among 98 adolescents in the Philippines, South Africa and Zimbabwe with an online survey of 655 participants from 92 countries indicated that approximately two-thirds of untested adolescents desired an HIV test (16). The WHO study included 13 of the 18 All In African countries. Individual country studies and surveys also indicate strong desire to test: between 47.8 and 85.5% of adolescents and youth want to be tested for HIV in West/Central (17,18,19,20), East (18,21,22,23), and southern Africa (24,25,26). The proportion of adolescents willing to test differed within and between some countries with respect to factors including gender, geographical residence, socio-cultural norms, and HIV knowledge and risk perception of participants. Overall, the proportion of adolescents willing to test was higher in later vs. earlier-conducted studies.

Given the low HTC rates, it appears that adolescents’ willingness to be tested is not matched by their HTC uptake, and factors reducing access to testing need to be elicited and addressed. The WHO adolescent HTC study evaluated barriers to HTC, categorizing them into personal, social, cultural, or service-related (16). The most frequently expressed barrier to HTC among untested adolescents was fear, including fear of needles, parents’ reaction to a positive result, AIDS-related illness, stigma/discrimination, and death (16). Interestingly, while ~20% of respondents expressed fear as a barrier, this proportion rose to ~53% among the African adolescents (16), suggesting that addressing multiple sources of fear (for example, debunking myths and exaggerations of truth with education and counseling) among African adolescents may be important to overcome barriers to testing. Other major barriers identified in the WHO study were the impact of a positive diagnosis, association of HTC with bad or high-risk behavior, lack of information, perceived risk with respect to sexual exposure, denial, poor attitudes of healthcare providers (poor confidentiality, insensitivity, and being judgmental), difficulty accessing testing services (transportation, cost, long waiting times, service hours), and parent/guardian consent requirements (16). Other studies conducted across sub-Saharan Africa corroborate with the WHO study with respect to barriers to adolescent HTC (18,20,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32). These studies identified major barriers as fear of a positive test, especially among those sexually active, and fear of stigma and discrimination, including being ostracized by friends and family. Fear of loss of current or future partners, and the potential psychological impact of these consequences, including depression and suicide, were also expressed by African adolescents (22,23,24,26,28,30,32).

Due to its legal implications, and likely wide cross-regional and country variation, age of consent for HTC amongst minors under age 18 y is treated separately. The next section singles out and discusses legal consent as relates to HTC among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa.

Legal Age of Consent and Adolescent HIV Testing in Sub-Saharan Africa

One of the major barriers to the uptake of HTC among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa is the requirement of parental/guardian consent for minors (33). The WHO reports that of 40 countries in the African region with defined laws on age of consent for HTC, less than half (19, 47.5%) have enacted laws supporting independent HTC to adolescents less than 18 y of age (33). The remaining 21 countries that do not have legislation supporting HTC for minors include 5 All In countries: Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, Nigeria, and Tanzania (33) ( Table 2 ). With the exception of Tanzania, all of these countries are in West and Central Africa. Lawmakers are often reluctant to reduce the minimum age of consent for sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, including HTC, out of the desire to protect the child, who may be viewed as too young or immature (9,33). With respect to HTC and SRH research among adolescents, these concerns have been countered with reassuring evidence and testing/recruitment approaches and strategies (34,35,36,37), however, challenges still exist with enactment and implementation of laws supporting HTC for minors. Even where the law permits access to HTC by younger adolescents or where parental/guardian consent can be sought, the behavior of healthcare providers may act as barriers due to the influence of socio-cultural norms consistent with limiting dialogue about sex, restricting services for HTC, judgmental attitudes during service provision to adolescents and determining appropriateness of caregivers to give consent (16,33,37,38,39,40,41). Furthermore, confusion about testing guidelines and regulations and concern for the ward’s increased vulnerability if HIV-positive, may limit healthcare providers’ offering of HTC as PITC (41). Nevertheless, the involvement of family in an ALHIV’s decision to test and their ward’s ability to cope after disclosure of a positive test has been shown to be critical (28). As much as independent adolescent testing should be made available, a supportive and involved family is desirable for optimal outcomes.

Testing Pregnant and Nonpregnant Female Adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa

In many African countries where adolescents have limitations in access to HTC and HIV care, early marriage at <15 y, especially amongst girls, is culturally and/or legally permissible ( Table 2 ) (33,42,43). These marriages are often arranged by parents and guardians without input from the adolescent (33,42). Among married adolescent girls age 15–19 y in six West African countries, only 16–26% state that they have a final say in their own healthcare (44). In this regard, early marriage and parenthood where not consistent with empowerment to make choices such as self-testing for HIV, is not necessarily a step toward adulthood and independence. The concept of “emancipated minor” in many of these countries is either nonexistent or poorly defined (33,43), making access to testing and other HIV/SRH-related services difficult for most adolescents.

In addition to relatively high HIV incidence, sub-Saharan African countries have some of the highest pregnancy rates among adolescents in the world ( Table 1 ). The high rate of adolescent pregnancies reflects poor access to family planning for this population and indicates the need for a more integrated and comprehensive approach to adolescent sexual health, including family planning and HTC. With the exception of Rwanda, all the All-In African countries are also priority countries for the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (45). Pregnant adolescent females living with HIV are a subgroup of African ALHIV that has received relatively little attention. These adolescents often have to contend with the double stigma of teen or preteen pregnancy and HIV; in African societies, both of these phenomena are regarded as indicative of sexual promiscuity. Unless pre- and early pregnancy HTC services for this marginalized group are scaled up, exposed infants and uninfected partners will continue to be at risk for HIV infection.

To date, only two studies, both from South Africa, have specifically evaluated HTC among pregnant adolescents accessing prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) services (46,47). One study was a cross-sectional survey in Kwazulu Natal (KZN) (46); the other was a cohort study with follow-up, in Eastern Cape (47). Ever-tested for HIV rates were similar (≥ 98%) between adolescent and adult mothers in the KZN study (46), likely facilitated by legislation supporting HTC for adolescents 12 y and older in South Africa (33). In the Eastern Cape study, adolescents were 1.4 times less likely to have tested for HIV prior to booking (47). Compared to adult women, adolescents experienced later entry into care, lower ART uptake or inappropriate ART administration, lower early infant diagnosis rates, and increased mother-to-child transmission of HIV (MTCT), stillbirth, and mortality (46,47). These studies highlight gaps in PMTCT service delivery for adolescents and higher risk of MTCT among adolescent HIV-positive mothers, even in the setting of optimized legal access to HTC. It is evident that legal access to HTC should be coupled with timeliness of testing and successful linkage to comprehensive services, particularly among adolescent females before and during pregnancy.

The Case for Expanding Adolescent Access to HIV Testing and Counseling by Lowering Age of Consent

In 2014, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) introduced new global HIV targets to be achieved by 2020. These targets were dubbed “90-90-90”: to have 90% of all people living with HIV knowing their status, 90% of all people diagnosed with HIV receiving sustained antiretroviral therapy, and 90% of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy achieving viral suppression (48). Up to 81% of African adolescents already living with HIV do not know their HIV status (38,39,49,50,51). One study from Zimbabwe reported that 80% of ALHIV in their study cohort were infected from MTCT and 15% from sexual transmission (51). Apart from the large gap in access to HTC, the lack of adolescents’ knowledge of their HIV status is partially attributable to low disclosure rates of HIV-positive status previously known to others (39,50,52). Expanding independent access to HTC allows maturing adolescents, especially the perinatally-infected and those not disclosed to, to discover their HIV status and to begin to take charge of their own health (25,40).

Restriction of independent HTC as an SRH service to individuals 18 y and older can be argued to be slowing progress in the provision of appropriate, impactful interventions for HIV prevention and quality HIV care amongst African adolescents (33,53). With the exception of Tanzania, ESA All In countries have more adolescent-friendly HTC laws and have higher adolescent HTC coverage than WCA countries, whose laws restrict self-consent for HTC to 18 y and above ( Tables 1 and 2 ). Legally-enabling environments are likely to promote not only the provision of clinical services but the conduct of research and the establishment of targeted health programs relevant to HIV among adolescents. Subsequently, adolescent-specific research findings can contribute to impactful policies on HIV prevention and control among African adolescents. Therefore, restrictions on independent access to critical adolescent SRH services including HTC may be contributing to a lack of, or weak policies for this population. This may be especially true for WCA, where the HIV epidemic is of a mixed nature (13) and PLHIV, including adolescents, may be more difficult to reach, test, and treat with current strategies and policies.

Recent cross-continental and global technical reports and guidelines have featured little or no input from the WCA region (9,54). Furthermore, recent significant funding initiatives targeted to pediatric and adolescent HIV treatment and prevention in sub-Saharan Africa such as the Accelerating Children’s HIV/AIDS Treatment and DREAMS initiatives (55,56,57) have involved few or none of the high-burden West and Central African countries. There have been high-level calls for quality strategic information and increased HIV/SRH research participation among all adolescents, especially in Africa (5,6,9). Southern and East Africa have led the region in implementing innovative approaches to adolescent HIV services, leaving West and Central Africa trailing behind (54). However, sub-Saharan Africa as a whole needs more efforts to improve HIV diagnosis and access to quality care and to reduce AIDS-related deaths among adolescents (8,9,33). One of the first steps in changing the status quo is the identification of as many ALHIV as possible: the road to 90-90-90 for African adolescents starts with wider access to independent HTC.

Enabling Strategies and Interventions to Improve Adolescent HIV Testing and Counseling

A rights-based approach should guide access to adolescent SRH and HIV care (37,58), including testing for HIV. Adolescents should be informed of their right to access stigma-free HIV testing and related services provided by respectful, competent staff, and they should participate in the development and implementation of relevant policies and practices. In order to achieve this, an enabling environment should be created within legal, socio-cultural, research and healthcare delivery contexts. Additionally, interventions should target barriers within these different contexts while taking transmission dynamics into consideration. For example, adolescents under age 14 y have no significant gender differences with respect to HIV prevalence, suggesting a nonsexual mode of HIV acquisition (59). However, beyond 14 y, female adolescents have much higher HIV incidence and prevalence as compared to males (7,8,59,60,61) ( Table 1 ). Pregnant adolescent females (46,47), adolescents with early sexual debut, married, or partnered but living separately, engaging in transactional sex, especially in rural areas (62,63), having multiple or older sexual partners (59,60,64), and those experiencing high mobility and labor migration (65,66), have also been identified to be at increased risk of HIV infection and unfavorable outcomes. Lastly, the significant proportions of perinatally-infected individuals surviving into young adolescence and young adulthood should not be overlooked (51,61,67). While advocating for and strengthening HTC uptake and coverage, linkage to quality care should be available to make HTC ultimately beneficial. Recent studies have cited early loss-to-follow-up, refusal of care, and nonreceipt of baseline CD4 as barriers to engagement in care among newly-identified ALHIV (68,69,70). We recommend the following measures to create an enabling environment for HTC among adolescents, including those at highest risk:

-

Enactment of laws expressly permitting independent access to HTC for adolescents less than 18 y of age across the WHO Africa region, but especially in WCA. The median age at sexual debut or age at which customary/traditional marriages are allowed can be used as a benchmark. It is critical for every country to have age of consent legislation that takes age of first exposure to sexual activity (within and outside of marriage) into consideration. This is especially important for girls. These laws should also be consistent with what HTC and SRH guidelines recommend in each country. Consultations among stakeholders, including adolescents and lawmakers, should be held to determine timeline and reference ages for revising HTC legislation. WCA countries can leverage on lessons learned from ESA countries that have already lowered their age of consent for HTC, to move this agenda forward.

-

Development of guidelines and laws for adolescents to independently provide consent for participation in SRH and HIV research. These guidelines and laws should be consistent with those governing the age of consent for routine SRH and HIV services. WCA countries have an opportunity to legislate concurrently for HIV/SRH services and related research since few countries may have pre-existing laws to that effect.

-

Involve both uninfected adolescents and ALHIV in policy-making and practice, from grassroots dialogue as advocates and advisors, to participation in healthcare delivery as peer counselors. Specifically for WCA, adolescents can play a role in increasing identification of undiagnosed ALHIV in highly-affected communities, groups or social circles. Other PLHIV who have already been tested and in care, including family members, can serve as index clients whose adolescent contacts may be tested for increased coverage.

-

Specialized certificate- or license-granting training on adolescent HIV, adolescent SRH service provision and adolescent health-related legislature, for healthcare providers. Emphasis should be put on skill-building in adolescent drug adherence and SRH counseling.

-

HIV seroprevalence, SRH surveys, and other HIV-related data should include younger adolescents 10–14 y old as well as disaggregate data to reflect trends in 10- to 19-y olds. Health surveys and other epidemiologic HIV data often exclude younger adolescents and have poorly-defined or poorly-disaggregated age categories with respect to adolescents (54,67). This limits the ability of funders and policy-makers to make evidence-based recommendations positively impacting on all adolescents and has further implication for mixed epidemic countries where detailed subnational data is necessary to know where testing should be concentrated. Furthermore, more data is needed on the source of infection for ALHIV (behavioral, perinatal through MTCT, or other) (7), especially in WCA, for targeted test and treat strategies.

Specific programming and research interventions to improve HTC among African adolescents should include the following:

-

Provision of adolescent-friendly healthcare facility HTC points of service, with strategies in place to tightly link and retain newly-diagnosed adolescents in care.

-

Expanding testing opportunities beyond healthcare facilities, specifically for female adolescents, for example among rural or out-of-school youth, street hawkers and market traders, in boarding schools, at points of purchase for condoms, and in antenatal care clinics. Given the high birth rates and worse maternal-infant outcomes for HIV- infected adolescent mothers, expanded HTC among adolescent females should be coupled with treatment for Sexually-Transmitted Infections and family planning to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

-

Strategies to improve caregiver involvement in testing, post-test disclosure and access to care for ALHIV regardless of mode of access to testing. Healthcare workers should counsel and support parents and guardians to disclose to their adolescent wards. In addition, parents and guardians of independently-tested ALHIV who need or wish to disclose should be educated and counseled to accept the positive diagnosis and to support their wards.

-

Behavior change communications programs, ideally with post-implementation measurement of impact, targeted specifically to adolescent, family, healthcare worker, law- and policy-maker stakeholders.

-

Engaging ALHIV and families of adolescents living positively with HIV to provide education and improve uptake of HTC among their untested peers, within and outside of the healthcare facility. Reassurance and alleviation of commonly-held testing fears among adolescents by experienced healthcare workers, other PLHIV and educated family members may make a large impact on poor HTC uptake.

Conclusion

In sub-Saharan Africa, where adolescent HIV burden is high, testing rates are low and outcomes most grim, several barriers continue to limit access to HTC. Adolescents desire to be tested for HIV, but those infected are often identified late or not at all, due to late or restricted access often influenced by cultural norms and biases. Removing legal barriers is only one step toward adolescents knowing their HIV status and accessing early and quality HIV care. Robust implementation research studies are needed to provide new knowledge to improve programming and policy for highly accessible HIV testing and care, such as: improved PMTCT service access for pregnant HIV-positive adolescents, community-based interventions to increase adolescent HTC in rural hard-to-reach communities, school-based interventions that integrate HIV education and on-site HIV testing, family involvement, and mobile testing.

This paper adds its voice to the calls for high-burden African countries to urgently address HIV testing and counseling barriers towards the improvement of HIV treatment outcomes for all infected adolescents.

Statement of Financial Support

There was no financial support for this work.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf.

Kasedde S, Luo C, McClure C, Chandan U. Reducing HIV and AIDS in adolescents: opportunities and challenges. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2013;10:159–68.

UNICEF. Global HIV Database, 2014. http://data.unicef.org/hiv-aids/global-trends.

UNICEF. Towards an AIDS-Free Generation: Children and AIDS-Sixth Stocktaking Report, 2013. http://www.childrenandaids.org/files/str6_full_report_29-11–2013.pdf.

World Health Organization. Health for the World’s Adolescents: a Second Chance in the Second Decade, 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112750/1/WHO_FWC_MCA_14.05_eng.pdf?ua=1.

UNICEF. 2014 Statistical Update: Children, Adolescents and AIDS, 2014. www.childrenandaids.org/files/Stats_Update_11-27.pdf.

Idele P, Gillespie A, Porth T, et al. Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among adolescents: current status, inequities, and data gaps. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66 Suppl 2:S144–53.

UNAIDS, UNICEF. All in to End Adolescent AIDS, 2015. http://allintoendadolescentaids.org/.

World Health Organization. HIV and Adolescents: Guidance for HIV Testing and Counselling and Care for Adolescents Living with HIV, 2013. http://www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94334/1/9789241506168_eng.pdf?ua=1.

WHO. Guidance on Provider-initiated HIV Testing and Counseling in Health Facilities, 2007. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595568_eng.pdf.

Baggaley R, Hensen B, Ajose O, et al. From caution to urgency: the evolution of HIV testing and counselling in Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:652–658B.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic, 2015. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2015/HIV_estimates_with_uncertainty_bounds_1990-2014.

World Bank Global HIV/AIDS Program. West Africa HIV/AIDS Epidemiology and Response Synthesis. Characterisation of the HIV Epidemic and Response in West Africa: Implications for Prevention, 2008. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTHIVAIDS/Resources/375798-1132695455908/WestAfricaSynthesisNov26.pdf.

UNAIDS. 2014 Progress Reports Submitted by Countries, 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2014countries/.

World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services. 5Cs: Consent, Confidentiality, Counselling, Correct Results and Connection, 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/179870/1/9789241508926_eng.pdf?ua=1.

World Health Organization. The Voices, Values and Preference of Adolescents on HIV Testing and Counselling, 2013. http://www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/95143/1/WHO_HIV_2013.135_eng.pdf.

Babalola S. Readiness for HIV testing among young people in northern Nigeria: the roles of social norm and perceived stigma. AIDS Behav 2007;11:759–69.

Biddlecom AE, Munthali A, Singh S, Woog V. Adolescents’ views of and preferences for sexual and reproductive health services in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi and Uganda. Afr J Reprod Health 2007;11:99–110.

Federal Ministry of Health Nigeria. National HIV & AIDS and Reproductive Health Survey (NARHS Plus II) 2013. http://nascp.gov.ng/demo/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/NARHS-Plus-2012-Final-18112013.pdf.

Haddison EC, Nguefack-Tsagué G, Noubom M, Mbatcham W, Ndumbe PM, Mbopi-Kéou FX. Voluntary counseling and testing for HIV among high school students in the Tiko health district, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J 2012;13:18.

Mbonye AK, Wamono F. Access to contraception and HIV testing among young women in a peri-urban district of Uganda. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2012;24:301–6.

Mwangi RW, Ngure P, Thiga M, Ngure J. Factors influencing the utilization of Voluntary Counselling and Testing services among university students in Kenya. Glob J Health Sci 2014;6:84–93.

Sisay S, Erku W, Medhin G, Woldeyohannes D. Perception of high school students on risk for acquiring HIV and utilization of voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) service for HIV in Debre-berhan Town, Ethiopia: a quantitative cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:518.

MacPhail CL, Pettifor A, Coates T, Rees H. “You must do the test to know your status”: attitudes to HIV voluntary counseling and testing for adolescents among South African youth and parents. Health Educ Behav 2008;35:87–104.

Ferrand RA, Trigg C, Bandason T, et al. Perception of risk of vertically acquired HIV infection and acceptability of provider-initiated testing and counseling among adolescents in Zimbabwe. Am J Public Health 2011;101:2325–32.

Fako TT. Social and psychological factors associated with willingness to test for HIV infection among young people in Botswana. AIDS Care 2006;18:201–7.

Denison JA, McCauley AP, Dunnett-Dagg WA, Lungu N, Sweat MD. HIV testing among adolescents in Ndola, Zambia: how individual, relational, and environmental factors relate to demand. AIDS Educ Prev 2009;21:314–24.

Denison JA, McCauley AP, Dunnett-Dagg WA, Lungu N, Sweat MD. The HIV testing experiences of adolescents in Ndola, Zambia: do families and friends matter? AIDS Care 2008;20:101–5.

Godia PM, Olenja JM, Hofman JJ, van den Broek N. Young people’s perception of sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:172.

Yahaya LA, Jimoh AA, Balogun OR. Factors hindering acceptance of HIV/AIDS voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) among youth in Kwara State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2010;14:159–64.

Uzochukwu B, Uguru N, Ezeoke U, Onwujekwe O, Sibeudu T. Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) for HIV/AIDS: a study of the knowledge, awareness and willingness to pay for VCT among students in tertiary institutions in Enugu State Nigeria. Health Policy 2011;99:277–84.

Munthali AC, Mvula PM, Maluwa-Banda D. Knowledge, attitudes and practices about HIV testing and counselling among adolescent girls in some selected secondary schools in Malawi. Afr J Reprod Health 2013;17(4 Spec No):60–8.

World Health Organization. Adolescent Consent to HIV Testing: a Review of Current Policies and Issues in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK217954/#annex15.s1.

Stanford PD, Monte DA, Briggs FM, et al.; Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health Project. Recruitment and retention of adolescent participants in HIV research: findings from the REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) Project. J Adolesc Health 2003;32:192–203.

Gilbert AL, Knopf AS, Fortenberry JD, Hosek SG, Kapogiannis BG, Zimet GD. Adolescent Self-Consent for Biomedical Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention Research. J Adolesc Health 2015;57:113–9.

Bekker LG, Slack C, Lee S, Shah S, Kapogiannis B. Ethical issues in adolescent HIV research in resource-limited countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;65 Suppl 1:S24–8.

Mburu G, Hodgson I, Teltschik A, et al. Rights-based services for adolescents living with HIV: adolescent self-efficacy and implications for health systems in Zambia. Reprod Health Matters 2013;21:176–85.

Mburu G, Hodgson I, Kalibala S, et al. Adolescent HIV disclosure in Zambia: barriers, facilitators and outcomes. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:18866.

Kidia KK, Mupambireyi Z, Cluver L, Ndhlovu CE, Borok M, Ferrand RA. HIV status disclosure to perinatally-infected adolescents in Zimbabwe: a qualitative study of adolescent and healthcare worker perspectives. PLoS One 2014;9:e87322.

Ramirez-Avila L, Nixon K, Noubary F, et al. Routine HIV testing in adolescents and young adults presenting to an outpatient clinic in Durban, South Africa. PLoS One 2012;7:e45507.

Kranzer K, Meghji J, Bandason T, et al. Barriers to provider-initiated testing and counselling for children in a high HIV prevalence setting: a mixed methods study. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001649.

UNICEF. State of the World’s Children Report: 2014 Statistical Tables, 2014. http://www.unicef.org/sowc2014/numbers/documents/english/SOWC2014_In%20Numbers_28%20Jan.pdf.

United States Department of State. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, Africa, 2013. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2013/af/index.htm.

UNAIDS. The Gap Report 2014: Adolescent Girls and Young Women, 2014. http://www.unaids.org/node/43455.

The Interagency Task Team for the Prevention of HIV in Pregnant Women Mothers and Children. Priority Countries, 2015. http://www.emtct-iatt.org/priority-countries/.

Horwood C, Butler LM, Haskins L, Phakathi S, Rollins N. HIV-infected adolescent mothers and their infants: low coverage of HIV services and high risk of HIV transmission in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One 2013;8:e74568.

Fatti G, Shaikh N, Eley B, Jackson D, Grimwood A. Adolescent and young pregnant women at increased risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and poorer maternal and infant health outcomes: A cohort study at public facilities in the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan district, Eastern Cape, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2014;104:874–80.

UNAIDS. 90-90-90: An Ambitious Treatment Target to Help End the AIDS Epidemic, 2014. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf.

Vreeman RC, Gramelspacher AM, Gisore PO, Scanlon ML, Nyandiko WM. Disclosure of HIV status to children in resource-limited settings: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18466.

Arrivé E, Dicko F, Amghar H, et al.; Pediatric IeDEA West Africa Working Group. HIV status disclosure and retention in care in HIV-infected adolescents on antiretroviral therapy (ART) in West Africa. PLoS One 2012;7:e33690.

Ferrand RA, Munaiwa L, Matsekete J, et al. Undiagnosed HIV infection among adolescents seeking primary health care in Zimbabwe. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:844–51.

Mutumba M, Musiime V, Tsai AC, et al. Disclosure of HIV status to perinatally infected adolescents in urban Uganda: a qualitative study on timing, process, and outcomes. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2015;26:472–84.

Folayan MO, Haire B, Harrison A, Odetoyingbo M, Fatusi O, Brown B. Ethical issues in adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health research in Nigeria. Dev World Bioeth 2014;15:191–8.

Pitorak H, Bergmann H, Fullem A, Duffy M. Mapping HIV Services and Policies for Adolescents: A Survey of 10 Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2013.

The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. DREAMS: Working Together for an AIDS-Free Future for Girls, 2014. http://www.pepfar.gov/partnerships/ppp/dreams/index.htm.

Birx D. PEPFAR, Nike Foundation and Gates Foundation Partnership Restores Hope for an AIDS-free Future for Girls, 2014. https://blogs.state.gov/stories/2014/12/09/pepfar-nike-foundation-and-gates-foundation-partnership-restores-hope-aids-free.

US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Accelerating Children’s HIV/AIDS Treatment Initiative, 2014. http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/232012.pdf.

Folayan MO, Harrison A, Odetoyinbo M, Brown B. Tackling the sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescents living with HIV/AIDS: a priority need in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2014;18(3 Spec No):102–8.

Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet 2002;359:1896–903.

Kembo J. Risk factors associated with HIV infection among young persons aged 15-24 years: evidence from an in-depth analysis of the 2005-06 Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey. SAHARA J 2012;9:54–63.

Mahy M, Garcia-Calleja JM, Marsh KA. Trends in HIV prevalence among young people in generalised epidemics: implications for monitoring the HIV epidemic. Sex Transm Infect 2012;88 Suppl 2:i65–75.

Aboki H, Folayan MO, Daniel’and U, Ogunlayi M. Changes in sexual risk behavior among adolescents: is the HIV prevention programme in Nigeria yielding results? Afr J Reprod Health 2014;18(3 Spec No):109–17.

Folayan MO, Adebajo S, Adeyemi A, Ogungbemi KM. Differences in sexual practices, sexual behavior and HIV risk profile between adolescents and young persons in rural and urban Nigeria. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129106.

Edelstein ZR, Santelli JS, Helleringer S, et al. Factors associated with incident HIV infection versus prevalent infection among youth in Rakai, Uganda. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2015;5:85–91.

Schuyler AC, Edelstein ZR, Mathur S, et al. Mobility among youth in Rakai, Uganda: Trends, characteristics, and associations with behavioural risk factors for HIV. Glob Public Health 2015:1–18.

Harrison A, Colvin CJ, Kuo C, Swartz A, Lurie M. Sustained high HIV incidence in young women in Southern Africa: social, behavioral, and structural factors and emerging intervention approaches. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:207–15.

Lowenthal ED, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Marukutira T, Chapman J, Goldrath K, Ferrand RA. Perinatally acquired HIV infection in adolescents from sub-Saharan Africa: a review of emerging challenges. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:627–39.

Tanner AE, Philbin MM, Duval A, Ellen J, Kapogiannis B, Fortenberry JD ; Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. “Youth friendly” clinics: considerations for linking and engaging HIV-infected adolescents into care. AIDS Care 2014;26:199–205.

Katz IT, Essien T, Marinda ET, et al. Antiretroviral therapy refusal among newly diagnosed HIV-infected adults. AIDS 2011;25:2177–81.

Nkala B, Khunwane M, Dietrich J, et al. Kganya Motsha Adolescent Centre: a model for adolescent friendly HIV management and reproductive health for adolescents in Soweto, South Africa. AIDS Care 2015;27:697–702.

Acknowledgements

We thank the African adolescents with whom we have worked over the years for their perseverance as we elucidate best practices for keeping them in excellent health. Above all, we thank them for educating us as we work towards this goal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sam-Agudu, N., Folayan, M. & Ezeanolue, E. Seeking wider access to HIV testing for adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatr Res 79, 838–845 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2016.28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2016.28

This article is cited by

-

A cross-sectional study on resilience, anxiety, depression, and psychoactive substance use among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents in Nigeria

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Protective factors for adolescent sexual risk behaviours and experiences linked to HIV infection in South Africa: a three-wave longitudinal analysis of caregiving, education, food security, and social protection

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Using the Implementation Research Logic Model as a Lens to View Experiences of Implementing HIV Prevention and Care Interventions with Adolescent Sexual Minority Men—A Global Perspective

AIDS and Behavior (2023)

-

Implementation Science for Eliminating HIV Among Adolescents in High-Burden African Countries: Findings and Lessons Learned from the Adolescent HIV Prevention and Treatment Implementation Science Alliance (AHISA)

AIDS and Behavior (2023)

-

Exploring the why: risk factors for HIV and barriers to sexual and reproductive health service access among adolescents in Nigeria

BMC Health Services Research (2022)