Abstract

A model for brain bilirubin uptake (BBU) predicts that BBU in jaundiced newborns typically depends on the plasma total bilirubin concentration (TBC) and the bilirubin-albumin dissociation rate constant (k1) rather than the unbound bilirubin (Bf). The model's validity was tested by 1) evaluating its requirement that k3 >>> k2, where k3 and k2 are the rate constants for BBU and Bf-albumin association, respectively, and 2) determining whether the calculated BBU is ≤5% of the bilirubin production rate, the approximate BBU expected if brain bilirubin levels are <1% of the miscible bilirubin pool as reported in the literature. The model was investigated using peroxidase test measurements of TBC, Bf, k1, and k2 from 185 jaundiced newborns. Mean k2 was compared with the reported k3 value of 0.08/s. BBU calculated from TBC and k1 was expected to be ≤0.005 μg/kg/s given the reported bilirubin production rate of 0.1 μg/kg/s. BBU calculated using Bf was also compared with the bilirubin production rate. The mean k2 of 8.9 L/μmol/s was greater than k3, and the mean BBU of 0.72 μg/kg/s exceeded the expected range of ≤0.005 μg/kg/s. However, mean BBU using Bf (0.00073 μg/kg/s) was within the expected range. A mathematical model calculating BBU as a function of TBC and k1 could not be validated. BBU calculated from Bf is consistent with the observation that <1% of the miscible bilirubin pool is distributed in the brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The rate of BBU in jaundiced newborns is generally thought to be a function of the plasma non-albumin bound or “free” bilirubin (Bf), and current thinking is that this tiny fraction of the TBC is an important indicator of the risk of bilirubin toxicity (1–3). Recent publications by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Institutes of Health aimed at improving the clinical management of jaundiced newborns recommend, among other things, more research into the relationship between Bf and bilirubin toxicity (4–6).

Bf is a function of the TBC, the fraction (α) of TBC bound [α = (TBC − Bf)/TBC ≈ 1 at clinically relevant TBC], the albumin concentration (A), and the bilirubin-albumin dissociation and association rate constants, k1 and k2, respectively:

equation 1

Because Bf is < 0.1% of plasma bilirubin but only about 90% of plasma bilirubin may be bound to albumin in adults (7), A in equation 1 may be considered the “average” concentration of all the plasma species reversibly binding bilirubin (e.g., HDL) and k1 and k2 the “average” constants without fundamentally changing the arguments that follow. Several recent studies suggest that Bf as measured by the peroxidase test is indeed a more sensitive and specific indicator of bilirubin toxicity than the TBC alone (3,8–10).

Despite these considerations, the clinical management of jaundiced newborns is conventionally based on the less reliable but readily obtainable TBC (4). Although this approach has been questioned (11), there is an often-overlooked but important paper that supports, in theory, the use of the TBC in most clinical situations. About 18 y ago, Robinson and Rapoport applied a general mathematical model they had developed for brain uptake of protein bound drugs to BBU (12,13). Their model predicts that at TBC levels below about 454 μM (27 mg/dL), the plasma factors determining BBU are TBC and k1. Bf becomes important only when the TBC is above 27 mg/dL or unusual circumstances are present (e.g., drugs that interfere with plasma bilirubin binding). Because k1 is a constant, BBU will therefore be directly proportional to TBC.

According to their model, as blood enters the cerebral capillaries, Bf is instantaneously taken up at a rate given by −k3 · Bf, where k3 is the net first order rate constant for brain uptake of bilirubin (they estimate k3 ≈0.08/s) (13). The instantaneous change in Bf caused by −k3 · Bf perturbs the equilibrium Bf (Bfeq) at which dBfeq/dt is zero per equation 2 below, and Bfeq rapidly falls to the steady state level Bfss, where dBfss/dt remains close to zero (equation 3) for the remainder of the trip through the capillaries.

Since dBfss/dt ≈ 0, equation 3 can be rearranged to give:

The general model (12) assumes that the perturbation of equilibrium (−k3 · Beq) is of such magnitude that Bfss <<< Bfeq, generating the inequalities k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] · Bfss <<< k1 · α · TBC and k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] <<< k3. Under these circumstances, equation 4 becomes:

From equation 5, it follows directly that BBU = k3 · Bfss ≈ k1 · α · TBC, the basis of the Robinson and Rapoport model. By combining the capillary transit time, α (≈1), k1, and k3 into the constant E (see equation 9 in “Methods”), which is the fraction of the TBC extracted during passage through the capillaries, they obtained equation 6, which gives BBU as a function of cerebral blood flow, the constant E, and the TBC (12,13):

The Robinson and Rapoport model for BBU has never been validated, but it exists in the literature as credible support (assuming little variability in the constants) for using only the TBC, at least when managing jaundiced but otherwise well term newborns whose TBC levels are below 27 mg/dL. In this study, we use measurements of TBC, Bf, k1, and k2 from a diverse population of jaundiced newborns to investigate the validity of their model by testing 1) whether k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] <<< k3 is a valid assumption in the derivation of their model (see equations 4 and 5), and 2) whether BBU calculated by substituting actual TBC and k1 measurements into equation 6 yields BBU values that are about 5% of the reported rate of bilirubin production (14), a necessary condition if the BBU is to produce brain bilirubin levels that are <1% of the miscible bilirubin pool as reported in the literature (15,16).

METHODS

Population.

We reviewed the medical records of 256 newborns who received plasma TBC and Bf measurements as part of their evaluation for newborn jaundice to obtain a set of TBC values and their corresponding Bf, k1, k2, and albumin concentration for use in the study as outlined below. The review of medical records for this purpose was approved by the California Pacific Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Hypotheses to Be Evaluated.

1) k2 <<< k3. equation 5 depends on the inequality k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] <<< k3, and Robinson and Rapoport estimate that k3 is about 0.08/s (13). Inasmuch as A − (α · TBC) will be numerically greater than 0.08 at all the TBC and albumin levels of the population, k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] <<< k3 will be true only if k2 <<< k3. We therefore tested the validity of the inequality k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] <<< k3 by determining whether k2 was substantially less than 0.08. If the assumption is not valid and the hypothesis rejected, all the mass action factors (TBC, A, k1, and k2) are the relevant plasma factors determining Bfss per equation 4.

2) BBU calculated using TBC and k1 (equation 6) will be ≤0.005 μg/kg/s. The mean bilirubin production rate reported for well, term newborns is 8.5 mg/kg/24 h or 0.10 μg/kg/s (14). Since it is estimated that <1% of the miscible bilirubin pool distributes in the brain (15,16), the model, if valid, should provide rates of BBU somewhere in the neighborhood of 5% or less (≤0.005 μg/kg/s) of the bilirubin production rate. For example, assume BBU is 5% of the bilirubin production rate and that the bilirubin excretion rate is 60% of the production rate (14). If 10% of the cardiac output is directed to the brain and x mg of bilirubin are produced in a period of time, 0.005x will be taken up by the brain and 0.6x will be excreted. Of the 0.4x remaining in the miscible bilirubin pool, 1.25% (0.005/0.4) will reside in the brain.

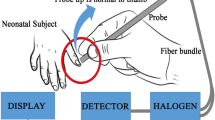

Measurement of TBC, Bf, k1 and k2.

TBC and the Bf were measured using an FDA-approved peroxidase method (Arrows UB Analyzer, Arrows Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) (17). HRP (EC 1.11.17) catalyzed oxidation of Bf by peroxide was measured at HRP concentrations of 23.8 μg/mL (0.54 μM) and 11.9 μg/mL to obtain Bf1 and Bf2, respectively. Two HRP concentrations are used to avoid underestimating Bfeq because, just as −k3 · Bfeq perturbs Bfeq during BBU (see equations 2 and 3), the onset of Bf oxidation, which is given by −kp · [HRP] · Bfeq, where kp is the bilirubin oxidation rate constant per unit HRP concentration (18) and [HRP] is the HRP concentration, also perturbs the equilibrium. Substituting kp · [HRP] for k3 in equation 4 gives (19):

In contrast to the requirement that k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] <<< k3 for the Robinson and Rapoport model (12), the peroxidase test requires kp · [HRP] <<< k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] if Bfss is to approximate Bfeq (19). When Bf2 > 1.05 · Bf1 (5% is the error of the method) the required condition is not met and Beq is underestimated at both peroxidase concentrations by at least 5%. Fortunately, the reciprocal of equation 7 provides a linear relationship between 1/Bfss and [HRP] with the reciprocal of the y intercept providing Bfss when [HRP] is zero, i.e., Bfeq:

In this circumstance (and assuming α = 1), k1 can be obtained from the slope of equation 8 as k1 = kp/(TBC · slope), following which k2 can be obtained from the intercept as k2 = intercept · k1 · TBC/(A −TBC) (19). The mean kp for the stock peroxidase was 18/s per μmol/L of HRP (SD 1.1, n = 16).

An important caveat is that sample dilution alters bilirubin-albumin binding in plasma as well as purified albumin solutions (20,21). Bfeq at the 42-fold sample dilution used in this study is likely to be much smaller than Bfeq in the undiluted sample, but it has been shown that the levels do correlate linearly (22). Dilution appears to primarily affect k2 rather than k1 (23) and because Bf is usually 2-to 5-fold lower at a 42-fold sample dilution (20,21), the impact of an order of magnitude increasein Bfeq or decrease ink2 on the results was taken into consideration when analyzing the data.

Calculation of BBU by equation 6 (the Robinson and Rapoport model).

BBU was calculated for each sample using equation 6. E was calculated from equation 9, which is derived from the general equation for E just above it using α = 1, the measured k1 for the sample, and the values provided by Robinson and Rapoport of 0.08/s for k3 and 1.75 s for the mean brain capillary transit time (τ) (13):

Inserting E for the sample along with the measured TBC and a cerebral blood flow of 0.5 mL/s/kg obtained from the reported blood flow rate 0.5 mL/s/100 g of brain (24) and a brain weight of 100 g/kg (25) into equation 6 provided BBU according to the Robinson and Rapoport model as:

Calculation of BBU using Bf.

If BBU is determined primarily by Bf, the instantaneous decrease in Bfeq as blood enters the brain capillaries is given by:

Integrating equation 11 between the time that blood enters the capillary (t = 0) and the time it exits the capillary (τ) during which Bfeq falls to Bfss, one obtains: equation 12

The fraction of Bfeq removed on passing through the brain capillaries, comparable to E in equation 10, is:

Fraction of Bf extracted

If k3=0.08/s and τ=1.75s, BBU is given as: equation 14

RESULTS

A total of 293 Bf measurements were made in a population of 256 jaundiced newborns. Of these, 198 samples from 185 newborns had Bf2 levels that exceeded Bf1 by 5% or more (mean 17%, SD 11%, range 6–69%). The mean birth weight and gestational age were 2401 g (SD = 1103, range 406–4483, n = 185) and 34 wk (SD 5, range 24–42 wk, n = 185), respectively. The mean TBC and Bf were 15.3 mg/dL (SD 7.0, range 2.8–34.2) and 1.12 μg/dL (SD 0.89, range 0.11–7.63), respectively. The mean Bf1 and Bf2 were 0.77 μg/dL (SD 0.55, range 0.09–3.83, n = 198) and 0.90 μg/dL, SD 0.66, range 0.10–5.1), respectively. Albumin was measured in 181 samples (91%), and the mean was 3.4 g/dL (SD 0.7, range 1.0–4.7). The various constants are given according to birth weight in Table 1.

Is k2 <<< k3?

The mean k2 (Table 1) was 8.9 L/μmol/s, which is numerically about 100 times greater than k3 (0.08). Even if undiluted plasma has a mean k2 two orders of magnitude less (0.089 L/μmol/s), the assumption required by the Robinson and Rapoport model that k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] <<< k3 will not be valid. Review of the literature provided no evidence that k3 might be substantially larger than 0.08/s (26), and assuming A underestimates the total concentration of bilirubin binding sites only reinforces the conclusion that the assumption is not valid.

Is BBU ≤0.005 μg/kg/s?

The mean k1 (Table 1) was 0.093/s. E calculated by equation 9 ranged from 0.001 to 0.036 (mean 0.010, SD 0.006), indicating that as little as 0.1% to as much as 3.6% of the TBC according to the model would be extracted as blood passed through the cerebral capillaries.

The mean BBU calculated using equation 10 (Robinson and Rapoport model) was 0.72 μg/kg/s (SD 0.52, range 0.057–2.7), with the calculated BBU exceeding the reported bilirubin production rate of 0.1 μg/kg/s in 193 of 198 samples (97%). Assuming BBU equals the bilirubin production rate (it could not proceed any faster), about 25% of the miscible bilirubin pool rather than the reported <1% should be found in the brain.

The mean BBU as a function of Bf (equation 15) was 0.00073 μg/kg/s (SD 0.00058, range 0.000073–0.0050), which is 0.73% of the bilirubin production rate and much more in line with the anticipated BBU of ≤0.005 μg/kg/s. Interestingly, if Bf is actually an order of magnitude higher in undiluted plasma (20–22), BBU would be about 7% of the bilirubin production rate and about 1.8% of the miscible bilirubin pool would be expected to reside in the brain. This is still very close to the value expected, and BBU by the total bilirubin model would either be the same or increase depending on the degree to which k1 is affected by dilution (k2/k1 decreases as Bf increases requiring some combination of a decrease in k2 and/or increase in k1). Even if k2 is an order of magnitude smaller, it still is 10-fold higher than k3.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that the Robinson and Rapoport mathematical model predicting that BBU will be largely a function of the TBC at TBC levels below 27 mg/dL is invalid when measured values for TBC and the bilirubin-albumin dissociation rate constant (k1) along with constants from the literature for brain bilirubin blood flow, capillary transit time (τ), and brain bilirubin uptake (k3) are applied to the model. Bfeq when k3 = 0.08/s and τ = 1.75 s will not fall sufficiently in the cerebral capillaries to meet the assumptions required for equation 5 to be operative. For the Robinson and Rapoport model to be operative, the expression in equation 13 must be nearly zero, indicating that virtually 100% of the Bf is taken up within a few milliseconds of the blood entering the capillary. This requires −k3 · τ to be much greater than previously reported. Since τ is unlikely significantly greater, k3 in humans would need to be orders of magnitude larger than the values reported in animals. Even assuming k3 = 80/s (1000-fold higher than the value in animals), at the mean k2 of our study (8.9 L/μmol/s), a TBC of 10 mg/dL (171 μM), and the mean study albumin of 3.4 g/dL (514 μM), k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] in equation 4 = 3052.7/s versus a k3 = 80/s, which clearly invalidates the assumption in equation 4 required by the Robinson and Rapoport model that k2 · [A − (α · TBC)] is so small relative to k3 that it can be ignored giving equation 5. Thus, all the plasma mass action variables determining BBU must be operative (TBC, A, k1, and k2), and because the fraction of bilirubin extracted during brain capillary transit is constant (equation 15), the overall amount of bilirubin taken up by the brain during capillary transit will be a function of Bfeq.

Our bilirubin-albumin binding data were from a diverse population of jaundiced newborns to provide a wide range of binding variables for the models, and because it was not possible to measure the bilirubin production rate, bilirubin pool distribution, and cerebral blood flow for each newborn, we applied our best estimate of each variable to the population. Variation in cerebral blood flow would apply to both models equally (equations 10 and 14) and not change the results. Because BBU by the Robinson and Rapoport model is 1000-fold greater than that by the Bf model, the BBU as a percentage of bilirubin production rate would not change greatly with variation in bilirubin production (even at triple the bilirubin production rate as occurs in hemolysis (14) BBU by the Robinson and Rapoport model still exceeds the production rate and BBU by the Bf model remains below 1% of the production rate). The percentage of the miscible bilirubin pool residing in the brain could also be in error by an order of magnitude (10% versus <1%) and BBU by the Robinson and Rapoport model would still far exceed the BBU predicted.

Considering the above, it is not unexpected that the BBU calculated according to the model (equation 10) was far too high relative to the bilirubin production rate for the model to be considered an accurate representation of BBU. BBU rates calculated using Bf as the operative plasma species (equation 15), however, are within the range expected assuming the reports that < 1% of the miscible bilirubin pool distributes in the brain are reasonably accurate and applicable to human newborns (15,16). Although sample dilution may systematically alter the binding variables (20–23), even when order of magnitude errors in the variables are invoked, the Robinson and Rapoport model still fails.

It is ironic that were the model correct, the variability in k1 (Table 1) would still require routine measurement of bilirubin-albumin binding, but the desired result would usually be k1 (to calculate E) rather than Bf. This paradoxical “inconstancy” of constants (Table 1) is a subtle but important reminder that there is considerable variability in plasma bilirubin binding in jaundiced newborns. If not, Bf could be calculated from the TBC and albumin, assuming albumin binds most of the bilirubin in plasma (7) We found a 73% coefficient of variation in k1 and a 158% variation in the equilibrium association constant (k2/k1). Cashore (27), using the peroxidase test and a single peroxidase concentration, has reported a 40% coefficient of variation for k2/k1 in well term newborns. The reasons for this variability are mostly unknown, but albumin dimerization and polymorphism (28) and small competing molecules generated during illness (29) may contribute. Variability in the nonplasma factors that can alter individual susceptibility to bilirubin toxicity, including interindividual variability in BBU, also deserve more study (30).

The Robinson and Rapoport model cannot be used as evidence supporting the use of the TBC alone when evaluating jaundiced newborns in any circumstances. Our data suggest that even if significant non-albumin binding of bilirubin in plasma occurs, Bf as measured by the peroxidase test provides rates of BBU consistent with the reported bilirubin production rate and miscible bilirubin pool distribution. Continued investigation of the usefulness of Bf measured in minimally diluted plasma (22) as an adjunct in the evaluation of newborn jaundice seems warranted.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

plasma albumin concentration

- α:

-

fraction of the TBC bound = (TBC–Bf)/TBC

- BBU:

-

brain bilirubin uptake

- Bf:

-

plasma free bilirubin concentration

- Bfeq:

-

equilibrium concentration of free bilirubin

- Bfss:

-

steady state concentration of free bilirubin

- E:

-

TBC extraction fraction

- HRP:

-

horseradish peroxidase

- k1:

-

bilirubin-albumin dissociation rate constant

- k2:

-

bilirubin-albumin association rate constant

- k3:

-

rate constant for the uptake of Bf by the brain

- kp:

-

rate constant for the peroxidase catalyzed oxidation of bilirubin by peroxide

- τ:

-

brain capillary transit time

- TBC:

-

plasma total bilirubin concentration

References

Diamond I, Schmid R 1966 Experimental bilirubin encephalopathy. The mode of entry of bilirubin-14C into the central nervous system. J Clin Invest 45: 678–689

Ostrow JD, Pascolo L, Shapiro SM, Tiribelli C 2003 New concepts in bilirubin encephalopathy. Eur J Clin Invest 33: 988–997

Ahlfors CE, Herbsman O 2003 Unbound bilirubin in a term newborn with kernicterus. Pediatrics 111: 1110–1112

American Academy of Pediatrics 2004 Clinical Practice Guideline. Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatrics 114: 297–316

Blackmon LR, Fanaroff AA, Raju TN 2004 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Research on prevention of bilirubin-induced brain injury and kernicterus: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development conference and executive summary. Pediatrics 114: 229–233

Stevenson DK, Wong RJ, Vreman HJ, McDonagh AF, Maisels MJ, Lightner DA 2004 NICHD Conference on Kernicterus: research on prevention of bilirubin-induced brain injury and kernicterus: bench-to-bedside—diagnostic methods and prevention and treatment strategies. J Perinatol 24: 521–525

Goessling W, Zucker SD 2000 Role of apolipoprotein D in the transport of bilirubin in plasma. Am J Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: G356–G365

Nakamura H, Yonetani M, Uetani Y, Funato M, Lee Y 1992 Determination of serum unbound bilirubin for prediction of kernicterus in low birthweight infants. Acta Paediatr Jpn 34: 642–647

Funato M, Tamai H, Shimada S, Nakamura H 1994 Vigintiphobia, unbound bilirubin, and auditory brainstem responses. Pediatrics 93: 50–53

Amin SB, Ahlfors C, Orlando MS, Dalzell LE, Merle KS, Guillet R 2001 Bilirubin and serial auditory brainstem responses in premature infants. Pediatrics 107: 664–670

Ahlfors CE, Wennberg RP 2004 Bilirubin-albumin binding and neonatal jaundice. Semin Perinatol 28: 334–339

Robinson PJ, Rapoport SI 1986 Kinetics of protein binding determine rates of uptake of drugs by brain. Am J Physiol 251: R1212–R1220

Robinson PJ, Rapoport SI 1987 Binding effect of albumin on uptake of bilirubin by brain. Pediatrics 79: 553–558

Maisels MJ, Pathak A, Nelson NM, Nathan DG, Smith CA 1971 Endogenous production of carbon monoxide in normal and erythroblastotic newborn infants. J Clin Invest 50: 1–8

Schmid R, Hammaker L 1963 Metabolism and disposition of C14-bilirubin in congenital nonhemolytic jaundice. J Clin Invest 42: 1720–1734

Davis DR, Yeary RA 1975 Effect of sulfadimethoxine on tissue distribution of [14C] bilirubin in the newborn and adult hyperbilirubinemic Gunn rate. Pediatr Res 9: 846–850

Shimabuku R, Nakamura H 1982 Total and unbound bilirubin determined using an automated peroxidase micromethod. Kobe J Med Sci 28: 91–104

Jacobsen J, Wennberg RP 1974 Determination of unbound bilirubin in the serum of newborns. Clin Chem 20: 783

Faerch T, Jacobsen J 1975 Determination of the association and dissociation rate constants for bilirubin-bovine serum albumin. Arch Biochem Biophys 168: 351–357

Ahlfors CE 1981 Effect of serum dilution on apparent unbound bilirubin concentration as measured by the peroxidase method. Clin Chem 27: 692–696

Weisiger RA, Ostrow JD, Koehler RK, Webster CC, Mukerjee P, Pascolo L, Tiribelli C 2001 Affinity of human serum albumin for bilirubin varies with albumin concentrations and buffer composition: results of a novel ultrafiltration method. J Biol Chem 276: 29953–29960

Ahlfors CE 2000 Measurement of plasma unbound unconjugated bilirubin. Anal Biochem 279: 130–135

Ahlfors CE, DiBiasio-Erwin D 1986 Rate constants for dissociation of bilirubin from its binding sites in neonatal (cord) and adult sera. J Pediatr 108: 295–298

Wintermark M, Lepori D, Cotting J, Roulet E, van Melle G, Meuli R, Maeder P, Regli L, Verdun FR, Deonna T, Schnyder P, Gudinchet F 2004 Brain perfusion in children: evolution with age assessed by quantitative perfusion computed tomography. Pediatrics 113: 1642–1652

Jordaan HV 1976 Newborn brain: body weight ratios. Am J Phys Anthropol 44: 279–284

Ives NK, Gardiner RM 1990 Blood-brain barrier permeability to bilirubin in the rat studied using intracarotid bolus injection and in situ brain perfusion techniques. Pediatr Res 27: 436–441

Cashore WJ 1980 Free bilirubin concentration and bilirubin-binding affinity in term and preterm infants. J Pediatr 96: 521–527

Lorey FW, Ahlfors CE, Smith DG, Neel JV 1984 Bilirubin binding by variant albumins in Yanomama Indians. Am J Hum Genet 36: 1112–1120

Gulyassy PF, Bottini AT, Jarrad EA, Stanfel LA 1983 Isolation and inhibitors of ligand:albumin-binding from uremic body fluids and normal urine. Kidney Int Suppl 16: S238–S242

Hansen TW 2001 Bilirubin brain toxicity. J Perinatol 21: S48–S51

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahlfors, C., Parker, A. Evaluation of a Model for Brain Bilirubin Uptake in Jaundiced Newborns. Pediatr Res 58, 1175–1179 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1203/01.pdr.0000185248.43044.cd

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/01.pdr.0000185248.43044.cd